By Richard Rule

On September 17, 1939, in the wake of Hitler’s invasion of Poland, the Soviet Red Army crossed the Polish frontier from the east. Within 10 days, the valiant Poles were completely overwhelmed and forced to surrender.

Partitioned between Germany and Russia, 77,000 square miles of Poland had now fallen into Soviet hands. In the months that followed the invasion, Stalin dissolved the Polish state and unleashed his security police, who, acting without restraint, orchestrated a campaign of terror to suppress all resistance.The very fabric of Polish society was soon being systematically torn to shreds, while over 1.5 million Poles were deported, arrested, or executed to facilitate the Soviet takeover of the nation.

Soviet Premier Josef Stalin’s designs on the men of Poland’s defeated army were no less frightful, and he decreed that the 240,000 Polish officers and men in captivity were to be treated as political prisoners. To this end the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, created a Directorate of Prisoners of War, under which most of the enlisted men found themselves dispatched to labor camps deep inside the Soviet Union.

The officers, however, were to be handled in a different manner. At least half were placed in the “special” prisons that had been created on the grounds of former Orthodox monasteries at Kozelsk, Starobelsk, and Ostashkov. Here, these men, recognized as Poland’s elite, were to undergo a rigorous “re-education” program incorporating lengthy interrogations and constant political agitation.

Stalin’s murderous designs on eastern Poland, however, were thrown into chaos by Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. The entire political landscape of Eastern Europe was to change once again as three million German troops poured through occupied Poland and into the Soviet Union itself. Stalin, a longtime antagonist of the West, suddenly found himself aligned with other nations already at war with Germany. In a dramatic turn of events, he now found himself allied with the Polish government-in-exile in London.

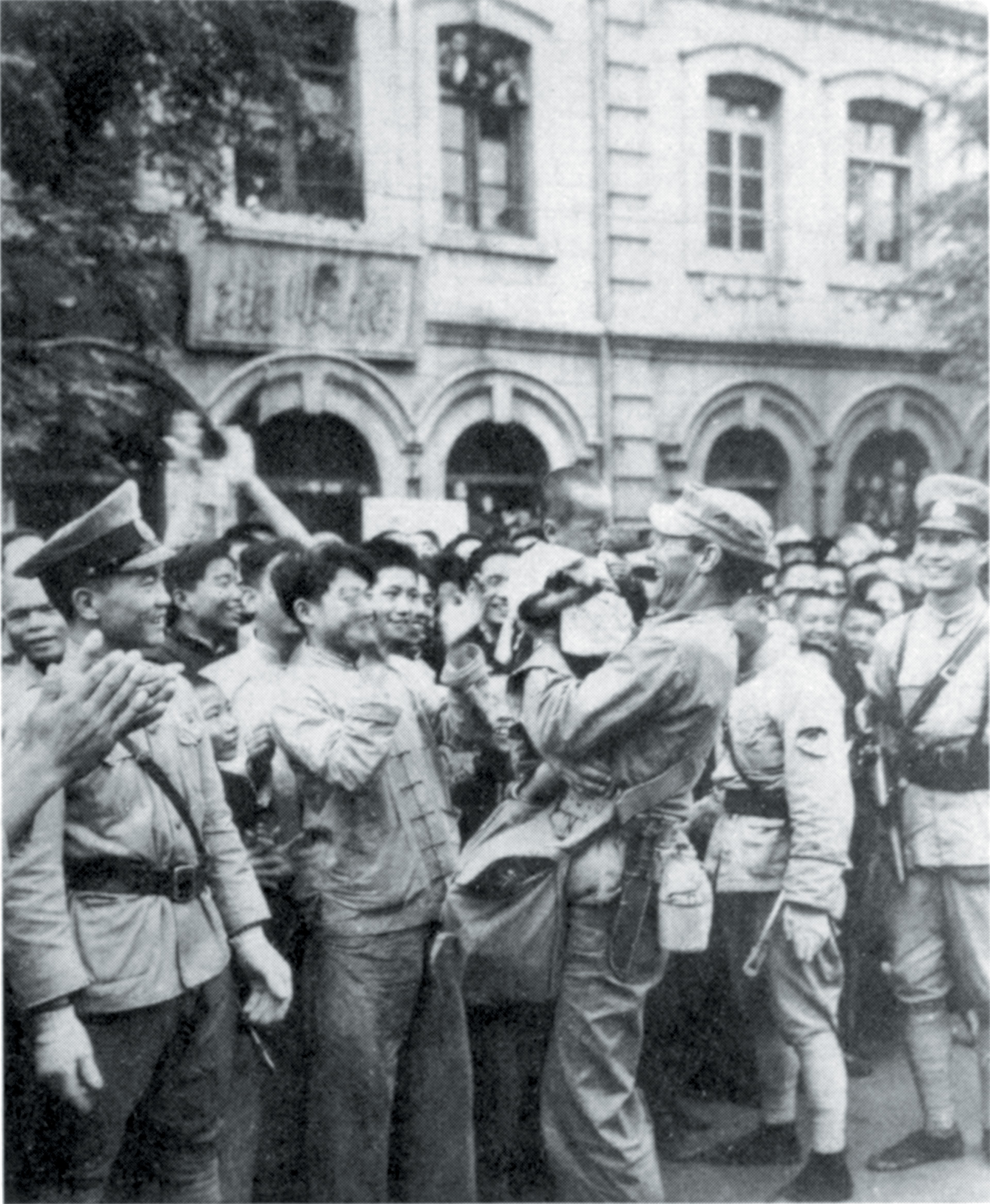

It was an uneasy alliance, but incredibly, now faced with a common enemy, Polish authorities and the Soviet Union agreed to form a Polish Army on Soviet territory drawn from the Polish prisoners interned inside the Soviet Union. The gates of over 138 Russian prison and labor camps were suddenly thrown open, allowing tens of thousands of emaciated Polish prisoners to make their way to a collection point at Buzul’uk where they would join with their new Polish commander, General Wladyslav Anders.

With so many men arriving daily from all parts of the Soviet Union, General Anders desperately needed officers to organize and process the troops, but strangely, very few appeared. When the camps had emptied and numbers were finalized, the Poles discovered that approximately 15,000 men, mostly officers and specialist NCOs, were still missing. Despite repeated Polish inquiries, the Soviets claimed to have no knowledge of their whereabouts; not even officials of the notorious NKVD, who maintained meticulous records, could shed any light on their fate. Stalin’s improbable view was that they had escaped to Manchuria!

For so many men to simply vanish within the Soviet prison system was incomprehensible to the Poles, and General Anders immediately established a search team to find his soldiers. The Russian authorities were far from helpful, but Anders’ team soon established that most of the missing men had been held in the prisons at Kozelsk, Ostashkov, and Starobelsk. Information regarding the prisoners held at Ostashkov and Starobelsk was scant, but the Poles learned that in the spring of 1940 the prison at Kozelsk had been systematically emptied and the prisoners taken under heavy NKVD guard to a location near Smolensk.

What became of them from there remained a mystery. The tireless search continued, but not a trace of the missing men was found. They had simply vanished. The Soviets were saying nothing, but Polish authorities in London suspected foul play.

More than two years would pass before a report from a Wehrmacht unit stationed in the Katyn Forest 12 miles west of Smolensk found its way to the desk of Germany’s Propaganda Minister, Dr. Josef Goebbels, in February 1943. Within a short time of reading the contents of the message, Goebbels had German radio broadcast to the world that they had discovered the mass graves of over 10,000 Polish officers in the Katyn Forest. The Germans claimed the victims, who had each been bound and executed with a shot to the back of the head, had formerly been prisoners of the Red Army and murdered in cold blood by Soviet security forces.

The Soviets vehemently denied the allegation, stating that the Nazis were clearly trying to cover up their own atrocity by blaming the Soviet Union. Soviet authorities claimed that in 1941 the Polish prisoners had fallen into the hands of the invading Germans and were in fact their prisoners. This stark revelation from Moscow left Polish authorities astounded; for nearly two years they had been led to believe that the Soviets had no knowledge of the missing men. Now, they were claiming otherwise.

Polish suspicions were further fueled by the location of the graves deep inside the Katyn Forest. The Poles had known that this location had for years been regularly used by Stalin’s security forces as an execution site to eliminate those who had opposed or displeased the Kremlin.

Many of the London Poles began to suspect that the Katyn killings were the work of the NKVD, but Nazi atrocities in Eastern Europe left few willing to believe the Goebbels version of the discovery. It seemed likely that the Germans were using the Katyn massacre to destabilize the Allied camp, and confirmation that the bullets used in the execution were of German manufacture served to strengthen the Soviet argument that the Nazis were, in fact, responsible. The Polish authorities in London were not convinced. German companies had supplied ammunition to many nations before the war, including the Soviet Union.

Far from being satisfied with the Soviet explanation, the Poles contacted the International Red Cross in Geneva, seeking an impartial investigation. Upon making their request, they were astonished to learn that the Germans had made a similar submission less than an hour before. Perhaps sensitive to the political machinations in play over the matter, the Red Cross made it clear that no inquiry could be undertaken unless they received a similar request from the Soviets.

Goebbels Delight; Stalin’s Fury

With political storm clouds building over the Western alliance, an outraged Stalin believed the Germans and Poles were now cooperating with one another. Goebbels was delighted. This is exactly what Berlin had wanted, and he counted on a swift and destructive reaction from the Kremlin. He was not to be disappointed.

Stalin, who had no intention of calling for an investigation, tersely demanded the Poles publicly declare their belief that the Germans were guilty of the crime. Not surprisingly, the Poles refused. Instead, they issued a statement that deliberately avoided singling out who they thought was responsible for the massacre at Katyn and merely condemned aggression against Polish citizens. The ink had barely dried on the Polish statement before Stalin vented his anger.

By mid-1943, the war had clearly begun to turn against Germany, and the destabilizing fallout from the Katyn affair was a damaging and unwelcome distraction for the Western Allies. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill tried to defuse the situation by encouraging the Poles to drop the matter, reasoning, “If they are dead, nothing you can do will bring them back.”

Desperate to repair the breach in the Allied front, Churchill assured Stalin that the Poles had not collaborated with the Nazis and were still willing to work with the Soviet government. The British Prime Minister’s placating maneuvers, however, had come too late— Stalin would not change his mind and proceeded to formally break diplomatic relations with the London Poles and set up a puppet Polish government in Moscow.

With the Allied camp fracturing over the Katyn disclosure, Goebbels drove the wedge deeper by instigating his own public inquiry headed by an independent international commission of distinguished forensic specialists drawn from neutral countries. To enhance the perception of impartiality, Goebbels invited a 12-person medical team from the Polish Red Cross (which secretly included members of the Polish Underground) along with journalists from numerous countries, including Sweden, Holland, Belgium, and Hungary. Granting the reporters unfettered access to the site, Goebbels was doing everything in his power to ensure that Katyn remained on the international stage as long as possible.

The Poles on the investigating team dismissed out of hand the Germans’ air of moral indignation over the killings and refused to do interviews for radio, make anti-Soviet statements, or tour Polish POW camps and lecture the prisoners on the Katyn atrocity. Their sole aim was to identify the murderers and pass the information back to London.

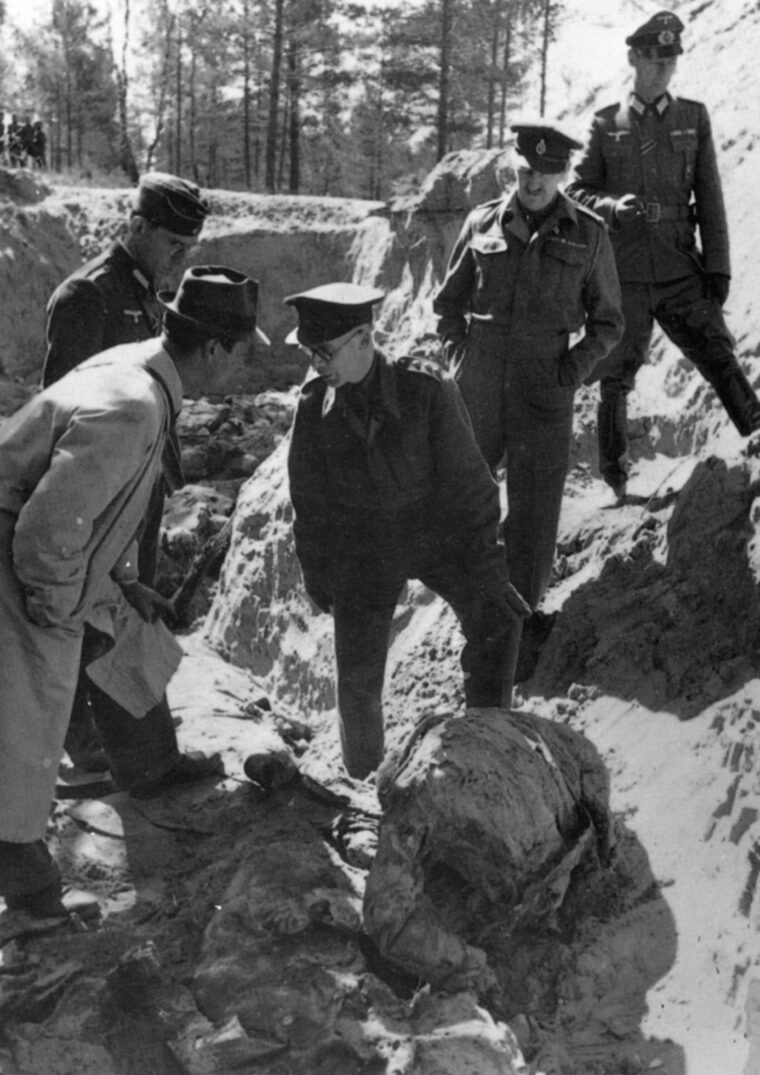

The frustrated Germans decided to have Polish and other Allied prisoners flown to the site in the hope that they would be more inclined to make the “appropriate” observations for propaganda, but they, too, refused to cooperate. Finally, in a blaze of German orchestrated publicity, delegates from the international commission, the Polish delegation, and a German Special Medical-Judiciary Commission began the macabre and grisly undertaking of inspecting the burial pits.

Eight graves were opened and found to vary in depth from six to 11 feet, holding 10 to 12 layers of bodies carefully arranged face down, one on top of the other. The victims had their hands secured behind their backs with white Soviet-made cord and were shot in the back of the head. A number of bodies were found to have puncture wounds consistent with the four-sided bayonet used by the Soviet military.

In a distressing discovery, some of the younger officers who had perhaps vocally resisted appeared to have had sawdust or rags stuffed in their mouths. Nearby, the bodies of Soviet civilians executed many years earlier were also unearthed, and it was noted that they were bound in identical fashion to the Poles.

The Nazis had originally announced in their broadcast that 10,000 bodies had been found, but despite efforts to persuade the Polish delegates to corroborate this figure the final tally was reduced to approximately 4,443. The wealth of personal items—letters, diaries, and identification disks—found confirmed that the victims were from the POW camp at Kozelsk. There was no doubt the information was authentic, as much of it had to be forcibly removed by cutting through pockets that had rotted closed.

Among the professional soldiers executed, the investigators also found 20 university professors; 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists. All had been reserve officers called to the colors during the German invasion.

The Polish community, which had hoped the Katyn discovery was a German hoax, was stunned to learn that the bodies of the Kozelsk prisoners were really there. The families of those missing from Starobelsk and Ostashkov were gripped by paralyzing fear. Had their men suffered the same fate? Nobody knew.

The key to the whole investigation quickly came to depend on establishing the date the massacre had taken place. The independent findings of three investigating teams determined from the condition of the bodies, the documents found, and the age of the trees that were planted over the graves, that the bodies had been in the ground for nearly three years. The teams placed the date of the executions somewhere around the spring of 1940, which was a year before the German invasion and at a time when the area was under the control of the NKVD.

This revelation was explosive and ignited public outrage on both sides of the Atlantic. While the British and American governments trod warily around the Katyn issue, the possibility that one Allied government had actually murdered much of the officer corps of another had shocked the world and left the public demanding answers.

It was a difficult position for the Western leaders. With the tide of the war having turned against the Nazis, they had no desire to fuel an internal quarrel to disrupt their relationship with Stalin. Looking beyond the Katyn controversy, the Western Allies did not want to jeopardize the possibility of Soviet troops joining them in the Pacific War against the Japanese and, as such, publicly accepted the Soviet countercharge that the Germans committed the crime.

Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt secretly harbored suspicions of Russian guilt, but neither establishing the identity of the murderers nor locating the whereabouts of the 10,000 Polish officers still missing appeared to be in their best interests. They chose to view it as a matter of concern for the Poles alone to deal with.

The political fallout from Katyn had not achieved the decisive split in Allied unity that Goebbels had predicted or hoped for, but he observed the growing rift with unbridled delight and noted in his diary, “The Poles are given the brush-off by the English and Americans as though they were enemies.”

When the Smolensk region was reoccupied by Red Army troops in September 1943, Soviet authorities began their own inquiry into the fate of the Poles. With no foreign representatives or Polish communists initially invited, the Soviet delegation, known as the Burdenko Commission after the surgeon who chaired it, immediately went to work discrediting the findings of the three previous investigating teams.

The 500 Russian Workers who had Carried out the Macabre Task were Themselves Shot and Buried.

One of the first tasks undertaken concerned the small cemetery established in Katyn by the Polish Red Cross for the disinterred bodies. With little ceremony or explanation, it was immediately destroyed by NKVD personnel.

The Burdenko Commission’s subsequent report on the massacre stated that the murdered prisoners had in fact been carrying out road construction near Smolensk until captured by the Germans, who found them too difficult to control. According to the Soviets, during the fall of 1941 the Germans had run out of patience and in great secrecy executed all of the Poles.

This claim was supported by local Russian witnesses, who stated that trucks packed with Polish prisoners were seen driving into the forest, followed a short time later by the sound of gunfire. This was confirmed by the German-appointed mayor of Smolensk, B.G. Menshagin, who confided to a colleague that the Nazis were exterminating the Polish prisoners in the Katyn area.

The Soviet report stated that the Germans had exhumed the bodies in 1943, removed all documentation beyond April 1940, and then reburied them. The 500 Russian workers who had carried out the macabre task were themselves shot and buried. Some weeks later, a staged discovery of the Polish graves was carried out by Wehrmacht troops and immediately labeled as a Soviet atrocity. The delegates who formed the German commissions were said to have fabricated evidence under Nazi coercion to incriminate the Soviets.

No one doubted the Germans were capable of the murders at Katyn; they had done far worse in Poland and elsewhere, but observers were puzzled as to why the Soviet report overlooked key points without explanation. First, if the men were murdered in September 1941, which was a very warm time of the year, why were the majority clad in heavy winter coats? Second, if the Poles had spent 16 months in a labor camp, why didn’t the officers’ highly polished leather boots show signs of wear and tear consistent with road construction?

According to those who visited the site, the boots on the bodies were in excellent condition, and the heels were not worn. Lastly, if the men had fallen into the hands of the Germans in June 1941, why hadn’t the Soviets admitted this when the search for their whereabouts first began some years earlier? The many inconsistencies within the report left the Poles deeply troubled, but without any hard evidence there was little prospect of unraveling the truth until after the war.

With the Katyn region now back in Soviet hands, Goebbels ensured that the evidence already in German hands was preserved at all costs. The letters, diaries, and other personal items were put in nine wooden crates and taken to the Polish Institute of Forensic Medicine in Krakow for processing and further analysis.

In close contact with their countrymen in London, members of the Polish Underground were encouraged to view exactly what the Germans had collected. A number of resistance men managed to closely examine a great deal of the material and noted that most diary entries abruptly ceased during April and May 1940. Research also revealed that this period coincided with the time the men had stopped writing letters home. With the German army being forced back toward its own border, the Poles were desperate to steal the boxes before they were moved out of reach or fell into the hands of the advancing Soviets. Unfortunately the theft was thwarted at the last moment.

It seemed the last earthly possessions of the murdered Polish officers had now become some of the most sought after items in Eastern Europe. Stalin, however, was satisfied that the Red Army’s contribution to defeating the Nazis would make it unlikely that the West would dare confront him over the Katyn matter after the war. Nonetheless, when Krakow fell to his troops, Stalin had agents immediately scour the city for the containers. The Germans, however, had already spirited them to Breslau, Germany.

By May 1945, both the Soviet security police and Polish Underground were in hot pursuit of an SS detachment that was transporting the cargo through Germany. The SS troops got as far as Radebaul near Dresden, but with the Red Army now only a few miles away the boxes and their contents were destroyed by fire. Nothing survived. For the time being, the matter of the Katyn massacre was lost among the euphoric worldwide celebrations of Nazi Germany’s defeat.

At the Nuremberg trials, the Soviet Union was handed the responsibility for prosecuting the Germans for their crimes against humanity in Eastern Europe. In spite of Stalin’s secret demand for sanitized disclosure of the Soviet Union’s own questionable wartime conduct, the Soviet prosecution team surprisingly included the matter of Katyn in the formal indictment against the Germans. Neither the American nor the British prosecutors were pleased by its inclusion and made their concerns known to their Soviet colleagues. They believed the Soviets not only lacked credible witnesses to support their case but were making a grave error in judgment if they expected that the court would accept on face value the Russian government report on Katyn as evidence of German guilt.

A number of the American and British prosecutors had already read the Soviet document, and despite its air of great realism they knew it to be false from beginning to end. Fearing that the Katyn affair could lead to a major embarrassment in open court, they tried to argue the Soviets out of their folly, but the latter were unmoved. Katyn stayed in the indictment.

Observers suspected that the Soviet team had little choice but to prosecute the Germans for such a widely publicized “Nazi” atrocity. Silence over the matter would have merely fueled the perception that the Soviets had, in fact, committed the crime. The German defendants at Nuremberg could scarcely believe the Soviets were including Katyn in the trial. They eagerly awaited the showdown over the massacre, and they expected it to show the world that many of Stalin’s henchmen should be sitting alongside them in the dock.

The hearing on the Katyn massacre commenced on July 1, 1946. The Soviet team proposed to deal with the matter of Katyn based solely on the “evidence” contained within their own report and petitioned the court to bend the rules of evidence to make their own state’s report binding.

The Soviets’ crude attempt to brusquely sweep the crime into the lap of the Germans without further discussion threatened to cause the proceedings to devolve into a judicial circus. German counsel opposed the move and gained a ruling allowing each side to present three witnesses. Not surprisingly, two very different versions of the story were aired in court.

The Soviet case hinged on establishing the date of the executions, and they brought forward a Bulgarian pathologist, Doctor Marko Markov, who had been a member of the international investigation team set up by the Germans in 1943. What was not widely known was that after the war Markov had been arrested by Soviet security police as an enemy of the people for being a signatory to the report incriminating the Soviet Union of the murders. Markov had endured months of imprisonment for aiding the Germans and had virtually come straight from his prison cell to Nuremberg to testify.

In the witness box, Markov recanted his original claims, announcing that his findings were faulty and had been made under duress. He was now adamant that the forensic evidence indicated that the bodies had been in the ground for no longer than 18 months, a claim supported by a Russian pathologist named Dr. Prosorovsky, who had been a member of the Soviet commission. The shootings, they claimed, had taken place in the autumn of 1941 and had been carried out by the German Staff Engineer 537 unit commanded by a “Lieutenant Colonel Arnes.” The Soviet team was confident that coupling the disclosure of the German unit responsible with the expert testimony of their witnesses had effectively laid the blame squarely at the feet of the Germans. The tactic, however, was about to rebound on them.

A Blameless Massacre?

In a remarkable development, German defense counsel produced the very officer identified as having been responsible for the murders. His appearance in court not only surprised the Soviets but brought into question the accuracy of their entire case. The Wehrmacht officer, Colonel Aherns, not “Arnes,” had commanded the 537th Signals Regiment, which occupied the Katyn area in late 1941. The German officer, who had volunteered to testify, endured rigorous cross-examination by the Soviets but was able to demonstrate that Soviet reports identifying his men as the culprits was wrong.

In 1941, Colonel Aherns’ men were deployed in the Katyn Forest, but his overstretched regiment had lacked the logistical support, manpower, and weapons to undertake executions on such a scale. The Soviet prosecutors then tried to blame an Einsatzgruppe extermination unit, which was in the in the district in the autumn of 1941, but once again they lacked the evidence to connect it with the murders. To the acute discomfort of the entire Allied prosecuting team, the Soviet case had completely foundered.

With the Soviet inability to conclusively prove German guilt, the German defense counsel pressed the court to determine who should then be made responsible for the massacre. The answer was short— no one. It was made clear to the German barristers that if Nazi guilt for the crime could not be proven it was not the function of the court to look for the murderers elsewhere. With the Germans absolved of blame, Katyn was abruptly dropped from the proceedings.

When the final judgment at Nuremberg was eventually delivered on November 1, 1946, the charges relating to the Katyn massacre were excluded without explanation.

The omission of the Katyn Forest massacre, compounded by the peculiarly inept Soviet handling of the case, outraged the Polish community. The Poles knew that there was copious evidence available to determine the identity of the killers had the tribunal insisted on a more thorough investigation. During the war, Polish soil had soaked up the blood of millions of foreign victims whose murders had been, in some way, avenged by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. However, the murderers of their own military elite had deliberately been left unrevealed and unpunished without protest.

In his memoirs, Churchill said of Katyn that the victorious governments decided that the issue should be avoided. Postwar relations made it clear that in order to secure the cooperation of Stalin in the organization of the United Nations the matter would never be probed in detail.

In the years following the war, Katyn was a forbidden topic in Poland, erased from the nation’s official history. Despite the censorship, the massacre itself and the fate of the other 10,000 men missing from the Ostashkov and Starobelsk camps remained an open wound that refused to heal. Many Polish historians and private citizens, buoyed by compelling evidence from Western sources, moved to have the crime investigated further. However, the communist government of Poland refused to countenance anything other than the official Soviet version that, since 1943, had blamed the Germans for the killings.

For 50 years, the Soviet files on Katyn remained closed until the era of Mikhail Gorbachev and glasnost in 1987. It was then that a joint commission was formed to investigate “blank spots” in the troubled history of the two nations.

Finally, in October 1990, the Soviet premier solemnly handed the Polish leadership a folder containing documents outlining the chilling truth. The NKVD, on Stalin’s direct orders, had been responsible for the killings.

As many had suspected all along, the massacre was not a rogue secret police action but a carefully and officially sanctioned operation that commenced soon after the cessation of hostilities with Poland in 1939. The principal targets were the Polish officers held in the three camps at Kozelsk, Ostashkov, and Starobelsk, who were at that time enduring an incessant barrage of Soviet propaganda and political re-education. Stalin did not feel threatened by the rank or military bearing of these men, but rather their standing as the professional and military elite around whom a resurgent, independent Poland could emerge.

From October 1939 to February 1940, the prisoners had been subjected to lengthy interrogations which, in effect, formed the basis of a selection process to determine who would live and who would die. With the exception of a few hundred prisoners, the NKVD categorized the majority as “hardened and uncompromising enemies of Soviet authority.”

That was all the reason Stalin needed, and on March 5, 1940, he signed an order condemning 21,857 prisoners to death. Every morning at 10 am, the camp commandant at Kozelsk would be contacted by NKVD headquarters in Moscow with a list of prisoners to be moved that day. Those selected were taken to a nearby railway station and transported to an undisclosed destination.

In the early hours of the morning, the first of the Kozelsk prisoners were detrained at a small station near Smolensk and, under the supervision of a grim-faced NKVD colonel, bundled into a bus with whitewashed windows. They were then taken along a road leading into the Katyn Forest.

Arriving at the destination, the Poles emerged from the bus and each was grabbed by a guard. The prisoners were led to the edge of the pit, and on the command of an NKVD officer the shootings began.

As the graves filled with hundreds and then thousands of men, the executioners were forced to climb down and rearrange the bodies to obtain an even distribution. During the next four weeks, the rest of the men at Kozelsk were murdered either in Katyn itself, in the basement of the NKVD headquarters in Smolensk, or at a nearby abattoir in the same city.

With the gruesome task completed, the last of the pits was covered with soil, and young pine saplings were planted over the mounds. Less detail is known about the executions of the other 10,000 men except that their fate was as final and absolute as those of the men from Kozelsk. Controversy still surrounds the exact locations, but the 3,841 men from the Ostashkov camp were believed to have been shot at Dergacki, near Kharkov, and 6,376 from Starobelsk were killed near Bologne.

The massacre of the 15,000 men, not including more than 7,300 other anti-Soviet military prisoners that were murdered, had been planned and carried out with great speed, secrecy, and skill and then covered up with an equal degree of shameful overt and covert support from other nations.

While the truth behind Stalin’s far-reaching killing fields and the circumstances surrounding the fate of the missing men had been finally laid bare, the place most commonly identified with the murders will probably always remain the Katyn Forest. It was the scene of only one of many cold-blooded mass executions committed during a war whose enduring legacy was the savage treatment inflicted upon noncombatants and prisoners alike.

Despite the Soviet Union’s remorseful disclosure of the facts behind the massacre, its assurances that any perpetrators still living would be brought to justice remains unfulfilled. To date no former member of the Soviet military or NKVD has ever been arrested or charged with the killings.

Richard Rule is a veteran of the Australian Army who has written several books, works in sales management, and enjoys fly fishing. He writes from his home in Heathmont, Victoria, Australia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments