By Donald J. Roberts II

The road that stretched through the pine and palmetto woodlands of central Florida was void of the usual animal chitter-chatter on the cool morning of December 28, 1835. Intruding on the usual hubbub of critter activity were 180 hiding Seminole warriors, arrayed along the western side of the road. As the Indians waited silently in their ambush positions, they slowly began to hear the clink and clank of approaching U.S. Army soldiers marching toward them.

These were 107 men under the command of Major Francis L. Dade. The major’s force had marched out of Fort Brooke near Tampa Bay six days earlier. They had been ordered to reinforce the garrison at Fort King, built at the site of present-day Ocala. The road Dade’s men marched along ran directly through the Indian reservation, which lately had become a place of violence. As the soldiers marched closer, the Seminole warriors prepared to unleash their attack upon the unsuspecting soldiers. From his hidden position in the high grass, Micanopy, a Seminole chief, aimed his rifle at the mounted figure of Major Dade. Seconds later, Micanopy’s shot signaled the other warriors to open fire on the soldiers.

Monroe’s “Revenge Against the Indians”

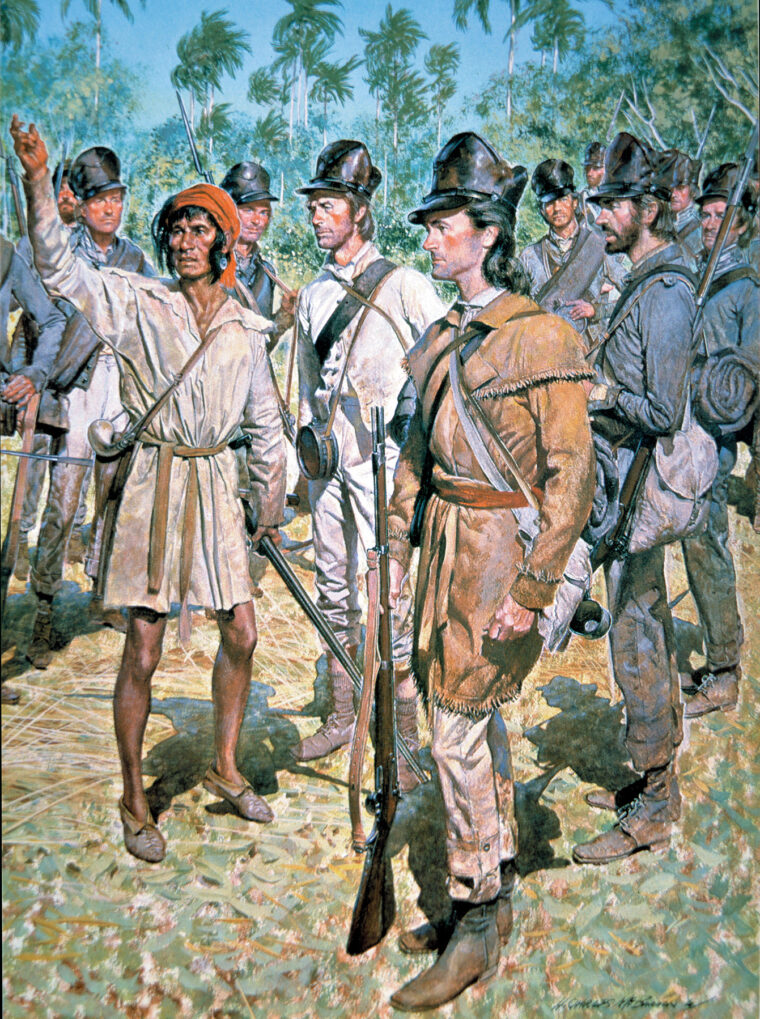

Armed conflict between the U.S. Army and Indians was not new to the Florida Territory in 1835. Following the American War for Independence, Regulars as well as militia had been used to protect settlers as they crossed the border into Spanish Florida. At the same time, Seminole settlements provided a safe haven for runaway slaves from the deep Southern states. Pressure from the wealthy planter class thus prompted government officials even more to act against the Indians. Skirmishes between whites and Indians eventually led to a full-scale battle in November of 1817. Forty-one soldiers and family members were killed in north Florida. As a result, President James Monroe ordered an expedition into Florida to “take revenge against the Indians.”

U.S. forces under the command of General Andrew Jackson invaded Florida and defeated the main Seminole forces in a timely manner by what later became known as the First Seminole War, 1817-1818.

With his easy victory over the Seminoles, Jackson decided to keep fighting. Now, however, most of the aggression was launched against the Spanish, who still maintained political control over the Florida peninsula. During the next four months, U.S. Army forces under the command of Jackson and General Edmund Gaines penetrated the Florida wilderness and captured every Spanish outpost in the territory. While Monroe had been pleased with the victory over the Indians, Jackson’s attacks against the Spanish were dimly viewed by the White House. Although many Americans believed that Spanish soldiers had instigated the Indian attacks against whites in Florida, Monroe returned the captured territory to the Spanish. However, Jackson’s military campaigns had “set the stage” for establishing Florida as a U.S. territory; at the same time, they signaled the beginning of the end for the Seminole Nation.

Although this First Seminole War ended in 1818, military incursions continued into Florida until the Spanish formally ceded it, allowing Florida to become an official territory in 1821. Almost as soon as Florida became a territory, the U.S. government began to urge Seminoles to leave their lands in Florida for reservations in present-day Oklahoma.

In order to begin the process of gathering up and systematically preparing the Seminoles for relocation, the American government signed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminoles in 1823. The treaty’s main purpose was to force the Indians onto a reservation in Florida, with the promise to supplement their diet with government rations and with the understanding they could remain on the reservation for the next 20 years. However, by year’s end many more Seminoles lived off the reservation than on it.

“If I had the Power, I Would Tonight Cut the Throat of Every White Man in Florida”

Within two years, bad soil and long periods of drought forced the hungry Seminoles who did live on the reservation to leave it in search of food. Many times the search included the slaughter of settlers’ cattle. Indians who were leaving the reservation joined with the more militant warriors who had never observed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek. One, who hated confinement, was Neamathia. He was a Mikasuki chief who had a strong hatred of whites. He wrote, “Ever since I was a small boy I have seen the white people steadily encroaching upon the Indians, and driving them from their homes and hunting grounds…. I will tell you plainly, if I had the power, I would tonight cut the throat of every white man in Florida.”

Increased violence between settlers and Seminoles led the Florida Legislative Council in 1828 to urge the U.S. Congress to remove all Seminoles from the Florida Territory. By 1827, Fort King had been built near the Indian Agency at Silver Springs to help control the marauding natives. The very next year, a road was built between Fort King and Fort Brooke.

As conflict continued with roaming bands of Indians, President Andrew Jackson’s administration remained committed to removing Indians from the Florida territory. A second treaty, the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832, was signed with a number of Seminole chiefs. The chiefs agreed to send a delegation to the Indian Territory in the West to inspect the land. This encouragement of the Indians to visit their proposed new homeland came on the heels of the government’s decision to stop supplementing the Seminole diet.

It is widely believed that the Indian delegation was shown only the most desirable land on the reservation. During the visit, a new treaty, the Treaty of Fort Gibson, was signed. The main emphasis of this new treaty spelled out a new time frame for the Seminoles to abide by. The new schedule called for the removal of all Seminoles from Florida within three years, one-third moving each year. According to Frank Mahon in his 1967 work History of the Second Seminole War, many believe that the government bribed the interpreters to cover up the full content of the treaty.

The signing of the Treaty of Fort Gibson infuriated the more militant Seminole chiefs in Florida. As a result, the job of Wiley Thompson, the newly appointed Indian Agent at Silver Springs, became very difficult. It was his job to encourage the Indians to adhere to the latest treaty (Fort Gibson). Many Seminoles simply did not want to move west because they feared the much stronger Creek Indians with whom they would be sharing the reservation. At the same time, many Seminoles believed that the U.S. government should honor the Treaty of Moultrie Creek and give them the full 20 years specified in that treaty.

Thompson’s report to President Jackson in October 1834 outlined the growing differences of opinions among the Indians, and the report reflected the increasing violence between whites and Seminoles. Jackson wrote back, “Let a sufficient military force be forthwith ordered to protect our citizens and remove and protect the Indians agreeable to the stipulations of the treaty.”

As unrest among the Seminoles grew, general distrust of the government increased as well. Violence between Indians and settlers in Florida reached unprecedented levels throughout 1835. An intense skirmish occurred between local militia and Indians near Gainesville in June, and in August Seminoles killed Private Kinsley H. Dalton while he was delivering mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King.

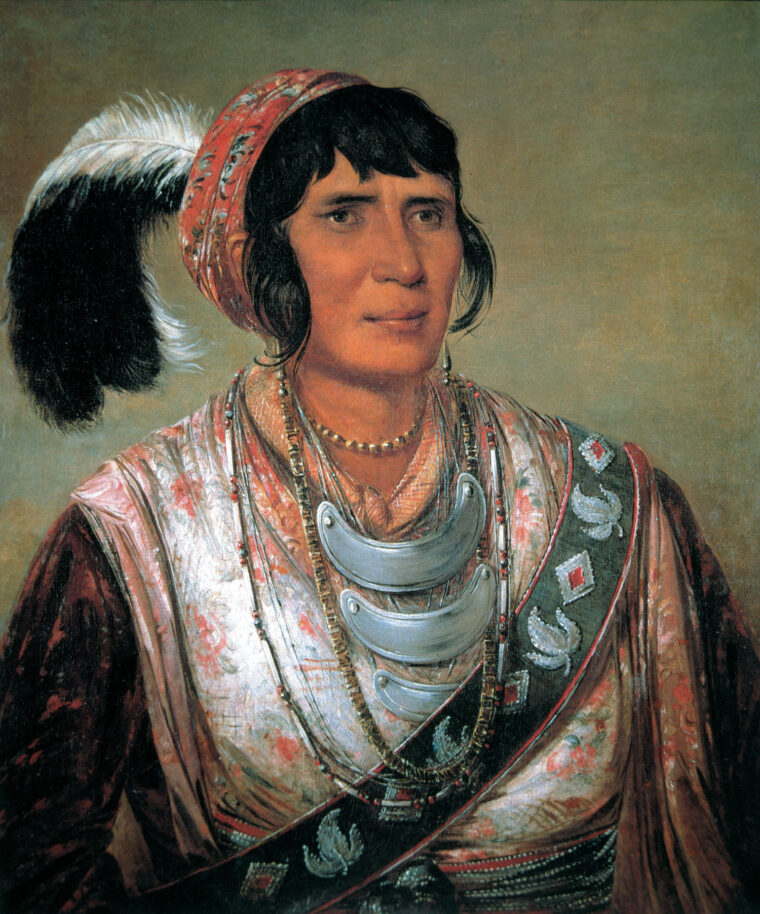

Osceola Planned Revenge Against Both Indians and the White Men

As growing Indian opposition against removal began to be organized behind leaders such as Osceola and Halpatter Tustenuggee (Alligator), General Duncan L. Clinch, commanding general in Florida, requested reinforcements from the War Department. It responded by sending 10 Regular infantry companies. Clinch stationed six at Fort King, three at Fort Brooke, and one at Key West.

In order to isolate some of the Seminole chiefs who organized opposition to relocation, Thompson had Osceola arrested and put in irons. Thompson tried to force the Indian chief into validating the Treaty of Payne’s Landing. Eventually, Thompson had to release Osceola, but the Indian never forgave the Indian Agent. “As far as Osceola was concerned, revenge must follow.”

Osceola decided to take his revenge out on Indians as well as whites. Charley Emathla, a well-respected chief, had decided to relocate to the western territory. On November 26, 1835, while returning home from auctioning off his cattle, Charley Emathla was ambushed by a group of Osceola-led Seminoles. Following a loud argument, Osceola shot Charley Emathla and left him dead on the trail. Osceola then scattered Charley’s money to the wind. When word of the ambush got out, near panic spread among whites as well as Indians.

Many of the Seminoles who were willing to relocate began to make camps near the stockade walls of Fort Brooke. Within weeks, there were nearly five hundred frightened Indians living near the fort, which was commanded by Captain Francis S. Belton. In order to keep the Indians from starving, Belton was forced to begin feeding them government rations. But Belton’s major concern was that the line of communication to Fort King had been severed by marauding bands of Seminole warriors.

Many whites throughout the Florida Territory began to gather together for protection against raiding bands of Indians. This was especially true in north-central Florida. From December 17 to the end of the month, there were several skirmishes between raiding Indians and militia units that had been called out by Governor John H. Eaton.

The first “pitched battle” of the Second Seminole War occurred on December 18, 1835. With Osceola as their leader, 80 Indians ambushed and then captured a train south of Gainesville. During this Battle of Black Point, 14 whites were killed or wounded. Within days, newly called-up militia arrived at the battle site and were able to reclaim some of the lost property. However, the “elusive” Seminoles could not be located.

This “wave of terror” that was sweeping the Florida peninsula had been the result of an on-going plan for over a year. Osceola and Alligator, along with other Seminole leaders, had as their objectives to steal food and cattle from settlers and strike against the federal government. The revenge-minded Osceola planned to kill Indian Agent Thompson as well.

Clinch Played Directly into Osceola’s Plans

Seminole leaders wanted to deliver as many blows against the paltry U.S. forces in Florida as possible. By the middle of December there were very few Indians remaining on the reservation. The usual groups of hostile Seminoles had all but disappeared from their usual “haunts.” Hiding out helped protect them from attack while they waited for opportunities to fight.

The chance the Indians were waiting for was not long in coming. In order to help protect his plantation and the surrounding area from marauding Indians, General Clinch had built a stockade (Fort Drane) about 20 miles northwest of Fort King. Clinch garrisoned Fort Drane with soldiers from Fort King, thus reducing the garrison there to only one company. This one maneuver played right into the plans of Osceola.

Reducing Fort King’s strength gave Osceola the opportunity to attempt the assassination of Agent Thompson. At the same time, Clinch ordered two companies from Fort Brooke to reinforce Fort King. When Osceola, Micanopy, and Alligator learned of this, they immediately began making plans to ambush the unsuspecting soldiers as they marched northward along the road running to Fort King.

Clinch’s order to Captain Belton to march to Fort King had Belton and his fellow officers puzzled. The two companies that Clinch had ordered northward would have no support as they made their way 100 miles through the heart of enemy territory. The officers considered waiting for promised reinforcements from New Orleans and Key West. But Clinch’s orders had specifically directed Belton to send two companies “as soon as practicable.”

On December 21, a ship did arrive from Key West. On board were Brevet Maj. Francis L. Dade and 38 men. They were not the reinforcements Belton had hoped for, but he would gladly accept them.

As deliberations continued concerning Clinch’s orders, a message arrived from Micanopy. It was translated as quickly as possible. “The Micasuki [a Seminole tribe] are gathering at the forks of the Withlacoochee, are already 250 strong, including 40 mounted. If the ‘Big Knives’ marched out—tried to force their way through the Seminole Nation—they would be killed.” Many officers inside Fort Brooke felt certain that following Clinch’s orders now would lead to certain suicide. But orders were orders.

Because Clinch’s order had arrived, the main question Belton had to answer was when to obey it. Two companies, unsupported, marching through enemy territory might wind up in a total disaster. On the other hand, one could wonder whether Micanopy’s message was false Indian bravado or a sincere threat.

Each Man Allotted 30 Bullets Each

The arrival of Dade and his men brought Captain George W. Gardiner’s C Company and Captain Upton S. Fraser’s B Company up to an acceptable strength. Belton finally decided that the time had come to follow Clinch’s orders. He could not delay any longer. B and C Companies would march in two days, on December 23.

Each man was issued 30 rounds of ammunition. This left only a small quantity of musket ammunition for Fort Brooke’s defense. Gardiner decided to bring a wheeled six-pounder along with 50 rounds of solid shot and grape shot. Four oxen were detailed to pull the cannon while a horse would pull the detachment’s supply wagon.

On the morning of the 23rd, Gardiner formed his men two by two, ready for the day’s march. At the rear of the column, the formation’s cannon and supply wagon waited for the command to march. At the last minute, Major Dade approached Gardiner and offered to take command of the column so Gardiner could stay back with his wife, who was very ill. Deciding to take Dade up on his offer, Gardiner galloped to the post hospital, leaving Dade in command of the operation.

Second Lieutenant William E. Basinger was given command of Gardiner’s C Company. Within minutes Dade was mounted, the stockade gates swung open, and when the order to “march” was given, 110 men began their trek northward toward Fort King.

As the formation cleared the confines of the fort, Dade put out his flanking guards into the palmettos and marshes. Marching was difficult on the Fort King Road. Recent rains had already soaked through the sand, making it loose and soft again. Wrote historian Frank Laumer in his 1995 work Dade’s Last Command, “There was a jingle of harness, the creak of leather, a screech of axles, and the muffled footfalls of an army. Long after the soldiers had crossed the ridge and gone from sight, the sound of their passage could still be heard by the watchers at the gate.”

Scouts sent by Osceola and Alligator watched Dade’s column leave the fort and then four miles up the road come to an abrupt halt. The oxen pulling the six-pounder were already played out. They would not take another step.

Log Walls Were Constructed to Slow the Seminole Attack

Major Dade was the only true infantryman in the formation. The balance of the force was red-legged infantry. That is, they were artillerymen somewhat trained to fight as infantry. The six-pounder bolstered spirits among the ranks. To Dade, the gun was a mild inconvenience, and its care and maintenance were not high on his priority list. He then decided to abandon the gun alongside the road and hitch the oxen to the column’s supply wagon. The men began casting nervous looks at one another. They had only marched four miles, and already they had lost their cannon.

With a slight increase in marching speed, the column was able to reach the Little Hillsborough River in time to prepare camp before dark. The men quickly went to work felling tall pines in order to construct a three-log- high wall around the camp to slow any Seminole attack. Fires were started and the evening meal eaten.

Back at Fort Brooke, the schooner Motto had arrived during the afternoon. One of its passengers was a slave named Louis Pacheco. He spoke fluent Seminole, English, Spanish, and French. At the same time, he was familiar with the territory between Fort Brooke and Fort King. Captain Belton immediately made arrangements with Pacheco’s owner to hire him for $25 a month. Pacheco was then sent out to catch up to Dade’s column in order to act as a scout and interpreter.

Belton received word from Dade that the column had abandoned the gun along the road. Because Gardiner had sent his wife to Key West for better medical treatment aboard the Motto, he volunteered to take two men and a team of horses to recover the cannon and catch up to the column. By 9 pm, Gardiner reached the camp at the river. Immediately, spirits lifted all around the encampment. The transformed artillerymen had their gun back.

At Fort Drane, General Clinch began to have second thoughts about his order to march two companies from Fort Brooke. He realized that they would have to force their way “a distance of one hundred miles, through the disaffected & hostile part of the Seminole Nation.” Clinch decided to change the earlier order to Gardiner and Fraser. Clinch wrote: “to the Commanding Officer of U.S. Troops, Ft. Brooke that, instead of two companies setting out alone, the four designated in a previous order will proceed to Ft. King. The Commg. Officer will use much caution on the march, and avoid any possible chance of a surprise.”

As the soldiers began to break camp for the second day’s march, Dade sent Pacheco ahead to scout the road. After five miles Pacheco began to smell smoke. He knew he was getting close to the Big Hillsborough River. He approached and discovered that a trading post was reduced to charred ruins, the bridge over the river was still smoldering, and a cow had been slaughtered in the middle of the road. It had not been killed for food. It was a clear threat.

“Micanopy Should be Coming in. Then They Would Kill the Soldiers.”

Pacheco reported back to Major Dade. Was this truly a sign of hostility? Dade laughed. “Hostile? No…. That’s old Bowlegs did that, Louis. He’s been in the guard house at Tampa. He got away a few days ago, and he did that out of spite.” Bowlegs (Boleck) was the brother of King Payne, who had been chief of the Alachua Seminoles around 1815. Pacheco risked a mild protest, muttering, “More than old Bowlegs did that.” The protest never reached Major Dade’s ears; he had already ridden on.

The bridge across the Big Hillsborough was unserviceable. Dade sent Private Aaron Jewell with a message to Belton stating that there would be a delay until the river could be forded. Dade requested reinforcements should they arrive by sail.

To the north, deep in the reservation, Indian scouts reported the movement of Dade’s men. Ote Emathla, another Seminole chief, knew that all time for talk was gone. Government soldiers were near. “Perhaps tomorrow Osceola would return from the agency where he had gone to see his friend, Thompson,” Emathla said. “Micanopy should be coming in. Then they would kill the soldiers.”

On Christmas morning, Dade’s third day of march, one company of infantry arrived by ship at Fort Brooke. Captain John Mountfort disembarked his men from the ship, and Belton reported to him on Dade’s situation. The two officers speculated that if Dade’s command were in peril, Mountfort’s men would be in a worse position. Nevertheless, Mountfort was willing to try and catch up to Dade. He would take his men out at first light.

Private Jewell volunteered to take a message back to Dade informing him of Mountfort’s forthcoming march. Belton gave Jewell the note, considering him “a Most Gallant Volunteer,” and wished him Godspeed.

At the Hillsborough River, the men of B and C Companies had spent another restless night. There was not a man present who did not realize the Seminoles were getting bolder. They had listened to the Indians yelling throughout the night and had even heard a few wild shots fired. Following a hasty breakfast of boiled coffee, fried bacon, and hard biscuits, Dade sent Pacheco across the chilling water of the Hillsborough with orders to scout the road ahead all the way to a spring named Hagerman’s Hole.

As Pacheco moved ahead out of sight, the advance guard waded across the river with its ammunition, knapsacks, and muskets held high above their heads. When half the main body had crossed, Dade ordered the supply wagon and six-pounder hauled across with ropes. Once the rear guard had crossed with still no sign of Indian activity, the column moved together through the heavy growth of oaks and hickory trees that grew near the river. The men were nervous, watching, expecting an attack at any moment from the dense growth on both sides of the road.

Within a few hours, the heavy foliage gave way to open pine barrens. The men’s confidence suddenly swelled, many remembering that today was Christmas Day. The advance guard increased its distance from the main body, flankers fanned out on either side, and the rear guard dropped back. No attack was likely now.

Before dark, the soldiers reached Hagerman’s Hole. Pacheco was there, waiting patiently. As the men took to the trees again with their axes, Pacheco made his report to Dade. He had seen an abundance of Indian signs. The grass had been flattened down throughout the woods on both sides of the road. Clearly the Seminoles had been there watching.

Dade’s Men Knew They Were Being Watched From Afar

At 11 pm, there was a shout in the dark, “Who comes there?!” Men began staggering up, loading their muskets. Then shouts were heard of “Corporal of the guard!” A man was brought through the lines. It was Aaron Jewell, back from Fort Brooke. “Damn! Went back twenty-two miles yesterday, came back today,” the men began to whisper. “Guess Seminoles ain’t no worry to him. Just walks right through ’em.”

Dade learned from Jewell that the reinforcements he had been waiting on numbered only 50 men, and they would not leave Fort Brooke until the morning. Dade thought that if his command of 108 were in danger, what would it be like for half his number burdened with pack horses? Dade continued to read Belton’s message, “From all this you can regulate your movements so as to allow the reinforcement to join you.” Dade was stunned. Regulate your movement? Did he [Belton] mean march back the way they had come? Or did he mean just sit here for two days? Dade decided that it did not matter to this detachment any longer what Belton thought. Dade sent a message back stating that he was pushing on toward Fort King in the morning.

In fact, Mountfort’s column never left Fort Brooke. The decision was made to wait at the fort for more reinforcements to arrive by sail before moving out to catch up to Dade’s force.

Every day since leaving Fort Brooke, Dade’s men knew they were being watched by the Seminoles, and at night the harassment of the soldiers increased. The Indians who kept the steady vigil upon the soldiers reported to Micanopy, Ote Emathla, and Alligator. As the reports came in, the Seminoles began to formulate a plan. Foremost was an idea that Osceola had explained to them some time ago. According to Laumer, many times “he [Osceola] had seen the soldiers’ willing submission to the orders of officers, the men who wore the gold and silver marks upon their shoulders, the long swords. It was easy to see the strength it gave the white men when, in battle, all would move and fight on a series of commands. It was also clear that if officers were killed early in battle the soldiers, leaderless, not thinking for themselves, might be more easily overcome, like a snake without its head.”

Although the white man’s tactical approach to battle differed greatly from the individualistic, independent style of the Indians, the Seminoles appreciated the army’s tactics and planned to use them to their advantage in the upcoming battle.

The next morning, the fourth day of march, drums sounded the roll of Assembly, and sergeants shouted their orders to form the usual double column. Dade instructed Pacheco to move ahead and scout all the way to the Withlacoochee River. The major hoped to reach the river by late afternoon.

The day’s march was uneventful. Second Lieutenants Robert Mudge and John Keais ensured that the flankers, advance, and rear guards held their positions and remained alert for any sign of enemy activity. After a few hours of march, the ground began to slope downward as the road neared the river. Pacheco returned with news of an abundance of fresh tracks in the hummocks on both sides of the river. To this, Major Dade responded angrily, “Oh I’ll go through if I have to fly sky-high.”

Their Last Night on Earth?

The men dreaded the upcoming leg of the march to Fort King. Between the Withlacoochee River and the Little Withlacoochee, there were 12 miles of swamps on both sides of the road. The soldiers knew that if the Indians were serious about making any trouble, it would undoubtedly be between the fork of the two rivers.

The bridge across the Withlacoochee was found in charred ruins. Dade ordered the men across as before. The march was continued on the other side, and within 30 minutes some high ground was found that would serve as the night’s camp. The familiar sound of axe on wood echoed in the forest. The night fortification was built. The men ate their evening meal and bedded down. Most believed this would be their last night on earth. The column’s present location deep within the swamp was vulnerable to a Seminole attack.

About 10 miles ahead, deep within the Wahoo Swamp, countless cooking fires crackled and spit in front of each Seminole lodge. Warriors had been swarming into the camp for days. Scouts reported to Ote Emathla that the “Big Knives” had already made it across the “Weewa-thlock-ko” (Withlacoochee). Ote Emathla knew that he had to strike the enemy soon before they reached the high, open ground that would give the white soldiers the advantage in battle. Where was Osceola? He had not returned from the Agency near Fort King. If this attack against the soldiers was to be what the Seminoles desired, which was, in Laumer’s words, “a blow of the Seminole Nation against the whites” rather than an “irresponsible” attack by a group of unorganized warriors, then the leaders of the Nation needed to be present for the fight.

White Man’s Country

By noon the next day, the fifth day of marching, the men of Dade’s column reached the Little Withlacoochee to find that the Indians had destroyed this bridge by fire as well. The soldiers immediately went to work felling trees across the narrow river to use as foot bridges. Again the march was slowed by river crossings; however, the men were able to march another two hours before settling into their night camp. Spirits were high now that the swamp was behind them. The soldiers had not felt this safe since leaving Fort Brooke. They were now in “white man’s country.” The terrain was dry with open fields of vision and high elevation. Most of the men felt that the Indians had been bluffing, had now let them pass. The strain on nerves and muscles crossing the swamp had been tremendous. Once again confidence swelled throughout the camp. The fires had never burned brighter. The jokes and kidding among themselves that soldiers often enjoy once again filled the camp.

At the same time, within the Great Swamp just to the north of Dade’s night camp, Micanopy had finally arrived. It would be a great and fine thing if Osceola could join the gathering, but the word was that he remained at the Agency. Scouting reports indicated that the soldiers were over an hour north of the Little Withlacoochee. Ote Emathla knew the spot. If the assembled warriors left camp at dawn, they could reach a location along the white man’s road “where the road swung close around a pond. An attack there would leave the soldiers no place for retreat, while the Seminoles, if not successful, could return to the swamp.” Ote Emathla made sure that his warriors would have sufficient time to pick their spots and prepare for the ambush.

Light rain had fallen during the night, but as the men stood in the morning formation on the sixth day of march, their spirits were high. From here on, swiftness became more important than caution. Dade ordered his advance and rear guards to their posts but did not put out flankers. Wading through the palmettos and high grass and watching out for rattlesnakes as well as Indians, the flankers would slow the march even more than the oxen had. The terrain was open anyway, extending the column’s vision far to either side of the road. Dade did order the dogs out as usual. The cries of the handlers could be heard up and down the line, “Sooby, boy, sooby!” Lieutenant Mudge led out the advance guard of six soldiers. When the guard was 200 yards ahead, the drummer sounded the marching beat, and Captain Gardiner led the double column of soldiers forward. Lieutenant William Basinger commanded both the rear guard and the six-pounder’s crew. When the column was well under way, Dade gave the command for route step, and the drumming stopped.

Dade had decided to keep Pacheco with the main column today. Tomorrow he would be sent ahead to Fort King to announce the arrival of B and C Companies. All of a sudden, the dogs began barking as they caught the scent of something in the woods. It turned out to be an old horse grazing among the pine trees. When the dogs were turned back out, Pacheco noticed that they “persisted in remaining on the road. They did not hunt through the woods nor bark with any spirit.” As if to pick up the men’s spirits after the false alarm, Dade swung around in his saddle and called to his men, “We have now got through all danger; keep up good heart, and when we get to Fort King, I’ll give you three days for Christmas!” Dade’s reassurance brought “smiles, shouts, and hurrahs” from the men.

“If You Do Not Fire the First Shot, I Will”

Sixty feet west of the road, Micanopy and Ote Emathla were lying next to each other under a stand of palmettos. Alligator lay hidden nearby. As the Indians watched the “Long Knives” approach, Micanopy realized that he knew the leader. He remembered that his name was Dade. He watched as the major trotted to the back of the advance guard following his message to the men about the belated holiday. Ote Emathla nudged his friend and whispered, “If you do not fire the first shot, I will.” Micanopy whispered back, “I will show you.” Micanopy then sighted his rifle on Major Dade just as the officer had taken a hard biscuit out of his pack and raised it to his mouth.

Micanopy’s shot struck Dade through his heart. The Indians heard the major cry, “My God!” before falling from his horse, dead before he hit the ground. In a second, 180 warriors raised up from under palmettos or stepped aside from behind pine trees and unleashed a staggering volley at the surprised soldiers.

Within seconds nearly half the soldiers were down. Most were dead where they lay. The remaining men could only watch as the action unfolded around them. Men continued to be shot from all angles except from the pond, which stretched to the east. Captain Gardiner, standing in the middle of the road and seemingly impervious to enemy fire, began cursing and shouting commands to force the men into action. Slowly, the men began to search out cover and return fire.

As Captain Gardiner took command, he noticed there was no sign of the advance guard. Dade, Fraser, and Mudge, along with six men, were all down and probably dead. Gardiner began yelling for the gun to be brought up. Suddenly everyone began yelling, “The gun! Bring up the gun!” The words were thrown out like a lifeline to a drowning man, “Bring up the gun!” The gun could be a rallying point and their major advantage.

As Basinger brought the gun forward, effective Seminole fire shot the gun’s team of horses. Advancing the cannon by hand, Basinger’s crew had the gun firing solid shot within minutes. Many rounds shattered pine trees, sending splinters into the attacking Indians. Soon, however, Basinger’s initial gun crew were all shot down. As the gun was traversed from side to side, the Seminoles would roll away from the direction of fire and lie flat and wait for the next fearsome discharge. As soon as the smoke cleared, they would jump up and fire at the crew before they could reload.

Slowly the Seminole attack pressed in on the soldiers without any signs of weakening. But Basinger decided to switch his fire to canister rounds, a move that began to change the momentum of the battle in favor of the soldiers. It was nearly impossible for the Indians to dodge grapeshot.

Within minutes, Indians who had willingly exposed themselves to the soldiers’ fire now began to withdraw into the pine woods away from the cannon. Ote Emathla and Alligator did not try to stop the retreat. They realized that each warrior had his own reasons for fighting the soldiers. They had come of their own free will, and they could leave in the same manner.

Lying with the dead of the advance guard, Pacheco remained still. When the ambush had started, he had fallen to the ground unscathed. After several minutes, a few Seminoles noticed that he was not dead. One of the Indians aimed his weapon at him. Another Seminole pushed the barrel up, saying, “Don’t kill him. That’s a black man. He is not his own master.” As the Indians retreated from Basinger’s cannon fire, they took Pacheco back into the woods as their prisoner.

Both Thompson and Smith Were Killed Instantly by Osceola’s Men

Meanwhile at the Agency, Osceola, along with a number of warriors, lay concealed in the underbrush around Fort King. The time had come for Osceola to take his revenge against Thompson. Although Osceola wished to be present both at Thompson’s destruction and at that of the relieving column on the march to Fort King, killing Thompson held a higher priority in his mind.

As Thompson and his dinner companion, Lieutenant Constantine Smith, strolled outside Fort King’s stockade walls, Osceola’s warriors opened fire on them from their concealed positions. Both men were killed instantly, Thompson being hit by 14 shots. He was then scalped and the trophy was cut into small pieces so that each participant could have a portion. Although other settlers in the area were killed in the raid as well, the Indians did not attack the 46 soldiers inside the walls of Fort King. When the killing was over, Osceola left for the ambush site to the south.

With the Indians retreating, Captain Gardiner, “God of War” (his nickname from his West Point days), sent men to retrieve the axes, and other soldiers to gather in the wounded and the ammunition from the dead. The now-familiar chopping started in earnest. Pine trees were felled, topped, and notched, and a triangular barricade slowly began to take shape. The fortification was similar to a rail fence, with openings as wide as eight inches between the logs. It was better than nothing. Gardiner ordered the six-pounder to the north side of the barricade and instructed Basinger to direct his fire to the west and north.

Inside the barricade the assembled looked more like patients in a hospital ward than men manning a fighting position. There were many more men wounded than not. The only officers unhurt so far were Gardiner, Basinger, and Dr. John Gatlin. When the Seminoles attacked again, Gardiner could expect about 40 men to be able to continue the fight.

A quarter-mile to the west, Ote Emathla and Alligator had stopped the withdrawal and began trying to convince the warriors to renew the attack. The two explained that a victory had been achieved, but an even greater victory could still be gained. Everyone had heard the soldiers cutting the trees down; the soldiers were not moving on. Once the big gun was silenced, the remainder of the soldiers could be surrounded in their “log box” and killed.

Whooping and Yelling Like Devils

Even after an hour of debate, Alligator would not give up. He said: “Some say no! Are you drunk, or sick, or women, to be afraid of a few white men? Have we forgotten why these soldiers are here? They are here to take our land, our homes, our lives. They will enslave our blacks. They come to ‘round us up’ like cattle, pigs, put us on their boats, send us to the western land. This is our land. We did not come here today to leave it, but to fight for it. Then fight, until we kill these soldiers! Let their death carry the message to ‘The Washington Micco, the Great Father,’ Andrew Jackson, that though he may despise us for being Indian, for being Seminole, yet he still must look upon us as men. Go back! Go back and kill them all!”

By the time Alligator had convinced most of the warriors to renew the attack, more Seminoles had joined the fight, though not Osceola. With shouts “like devils, yelling and whooping,” the Indians swarmed through the pine trees in order to launch their second attack against the soldiers.

As soon as the attacking enemy came within range, Gardiner ordered the firing to begin. He took up position in the middle of the barricade, directing fire while Basinger commanded his field piece. Behind the barricade, the men were loading and firing as fast as they could. The “boom” of the cannon was a heartening victory every time Basinger’s men unleashed its fury.

Sand, blood, sweat, and tears were everywhere. Some men cursed while others cried. Over the sound of battle, Dr. Gatlin’s voice could be heard as he kneeled behind the lattice-work, “Well, I have got four barrels for them!” Those were the last words he spoke.

It became difficult for Basinger to keep up a steady volume of fire because the Seminoles targeted the exposed crew of the gun with renewed vigor. Crewmembers fell in succession, but new men jumped up to help service the gun. Then ammunition began to run out and the Seminoles pressed their attack as never before. Then the gun’s supply of shot was completely gone. The enemy closed in on the barricade from three directions.

Exposing himself repeatedly, Captain Gardiner was hit several times by rifle shots. He stumbled to a nearby pine tree for support. But he was finished, and he knew it. “I can give you no more orders my lads, do your best!” He then dropped his musket and fell to the ground.

With the gun silenced, Gardiner gone, and only about 12 men alive, the Seminoles advanced almost to the barricade itself. Men began shouting for more ammunition.

There was none. Basinger, who was the last officer standing, took bullets through both legs. He fell, immobilized. Minutes after that, the Indians overwhelmed the few remaining soldiers.

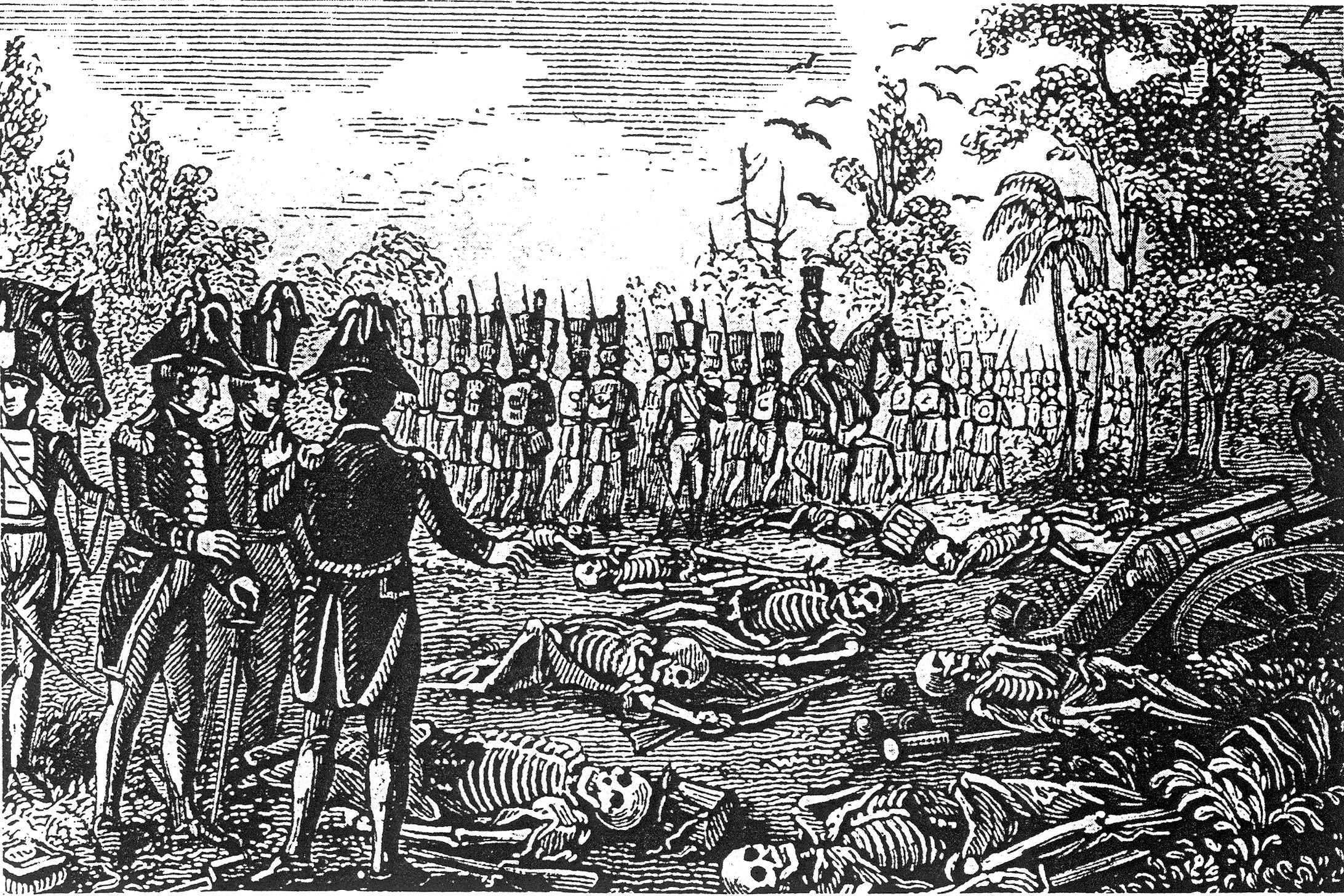

The Seminoles Left Behind a Scene of Total Devastation

Ote Emathla, Alligator, and Micanopy advanced along with their warriors. Micanopy and Ote Emathla explained to their men that “the plan was to kill, not to steal.” The soldiers’ weapons were to be their spoils of war. There was to be no stealing of personal items from the dead white soldiers. As the Indians moved in among the dead, two soldiers jumped up, startling the Seminoles. One tried to bargain for his life but was shot down on the spot. Another clubbed an Indian, killing him. As the soldier tried to run away, he was chased by two Indians on horseback and shot down as well.

Within an hour after the last shot was fired, the Seminoles began moving back into the swamp bordering the battlefield on the west. They left behind a scene of total desolation. Broken equipment, damaged muskets, bayonets, and ramrods lay scattered everywhere in the sand.

But the Indians mistakenly had left behind two soldiers who were alive. One was Private Ransom Clark and the other Private Edwin DeCourcy. It was past sundown by then but the two men somehow found each other through the dark and their pain. Clark had been wounded four times, DeCourcy twice. They had no water, food, or boots. They both decided that it would be best if they headed south and tried to make it back to Fort Brooke. Struggling, they set off.

Deep in the Wahoo Swamp northwest of the battle site, Seminoles celebrated their victory throughout the night by passing around trophies they had won in battle such as uniform parts, weapons, and various other pieces of the soldiers’ equipment they had gathered up from the ground. Osceola and his group of warriors then came into camp. When Osceola had described his raid on the Indian Agency, Ote Emathla and Alligator explained the day’s battle against Dade’s men. More whoops of joy echoed in the night.

At noon the next day, Clark and DeCourcy were continuing their struggle toward Fort Brooke. Suddenly they saw a Seminole ahead sitting on his horse and loading a rifle. The two soldiers decided to split up, each sneaking into the woods on either side of the road so they could hide. Within a few minutes, Ransom Clark heard two shots. Then the Indian “came riding through the brush in pursuit of me, and approached within ten feet…. Suddenly, however, he put spurs to his horse and went off at a gallop.”

Checking on DeCourcy, Clark found him dead. Crawling and limping on by himself for the next three days with nothing but water for nourishment, Clark reached Fort Brooke. A second survivor, Private Joseph Sprague, wandered into the fort a day after Clark’s arrival. The two soldiers’ accounts of the battle agreed. Dade and the remainder of his command had all been killed.

Slowly, the story of the Army’s defeat in Florida began to spread throughout the country. Captain Belton wrote an official report to Governor Eaton in Tallahassee. It detailed the Seminole victory. Newspapers printed stories about how the government should be “up and be doing! Send … armed volunteers … to Florida; and extirpate the Seminoles. The best in the army lie bleaching in the air.”

Victorious, But For How Long?

In the weeks following Dade’s massacre, increased numbers of Army, Navy, and Marine Corps troops were sent to Florida. Along with the Regulars, large numbers of militia were mobilized as well. Six weeks after the battle, General Gaines brought a thousand-man force into Fort Brooke. On February 13, 1836, Gaines, following Dade’s route of march, led his brigade into the Indian territory. When the brigade arrived at the battle site, the unrecognizable remains of Dade’s command were buried in a military ceremony while the brigade’s band played a funeral march. On the 22nd, Gaines led his men into Fort King. At last the fort was reinforced.

To the Seminole chiefs including Ote Emathla, Halpatter (Alligator), Micanopy, Osceola, and many others, the massacre of Dade and his soldiers had been a great and wonderful victory. They believed it had sent a strong message to the white men that the Seminoles would not be pushed around like chattel. They would fight for their homelands, make the whites go back and leave them in peace.

But the killing of Dade’s column sparked the Second Seminole War into flames. For seven years, battles continued throughout the interior of Florida, some as far south as Lake Okeechobee. Nearly four thousand soldiers and Indians died before the war ended in 1842. Osceola died in captivity at Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) in 1838. Micanopy was taken prisoner under a flag of truce and transported to Fort Gibson in the western Indian Territory. Ote Emathla and Alligator both surrendered to General Zachary Taylor and relocated to the west. Louis Pacheco survived the battle and lived until sometime around 1880.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments