By John Walker

The humiliating seizure of the American spy ship Pueblo on January 23, 1968, by North Korean gunboats proved both an enormous intelligence setback and a searing indictment of America’s Cold War policy. With their opening salvo of cannon and machine-gun fire aimed almost point-blank at the ship’s pilothouse, the North Koreans blew away both Pueblo’s main line of defense and the time-honored respect for the freedom of the seas. The attack also revealed the defenseless nature of the ship, her mission, and the entire concept behind it.

The stain on American honor started with Naval Intelligence and the National Security Agency (NSA), the originators of the spy ship program and Operation Clickbeetle, which sent the poorly armed Pueblo into hostile waters off North Korea’s east coast in the first place. Also coming in for a share of the blame were the planners who assessed Pueblo’s mission as one of minimal risk, the chain of command in Hawaii and Washington that seconded it, and the Lyndon Johnson administration’s unsophisticated interpretation of international relations as a bipolar rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Had American policymakers regarded North Korea as a country with its own national agenda, rather than as an auxiliary serving a global communist conspiracy headed by the Soviet Union, the Pueblo incident might have been avoided or resolved more effectively. The warning signs were there for all to see: the hostile actions of the North Koreans in 1967 alone—they violated some 542 times the 1953 armistice agreements that ended the Korean War, killing and wounding a number of American and South Korean soldiers alike—should have alerted American planners that the North Koreans’ supreme leader, Premier Kim Il-sung, was more than ready to act unilaterally, especially after severe economic hardships and political dissent compelled him to find a way to distract his people from their plight.

In the nine months before Pueblo’s capture, 20 South Korean fishing vessels had been illegally seized by the North Koreans for allegedly entering their territorial waters. The North Koreans violated the armistice terms 40 more times just in the first month of 1968, and 40 hours prior to the attack upon Pueblo dispatched a 31-man commando team across the Demilitarized Zone separating the two Koreas in a brazen, though unsuccessful, attempt to assassinate the president of South Korea, with the United States Embassy as a secondary target.

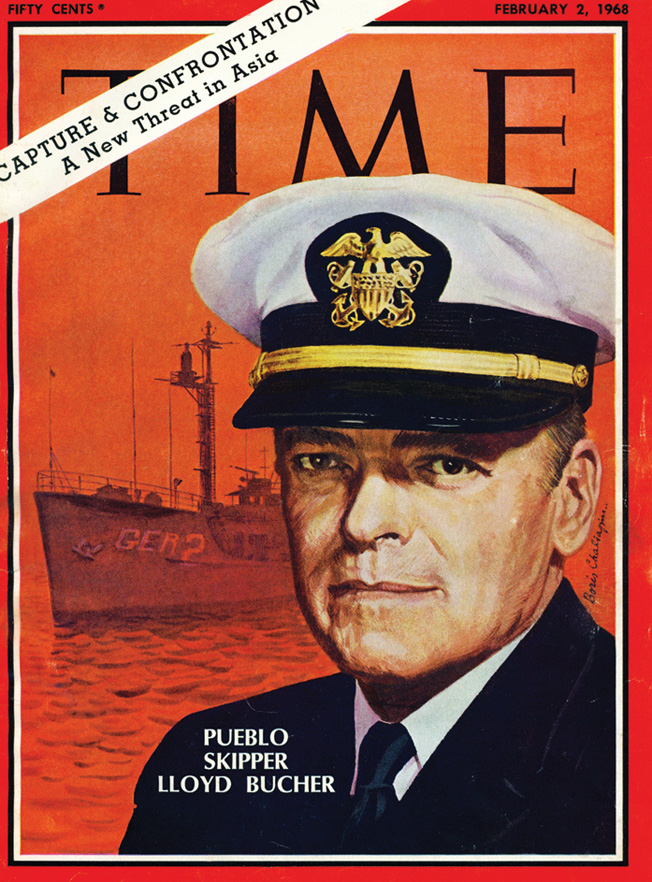

With one day remaining on Pueblo’s first mission, which had been uneventful to that point, it was decided not to inform her captain, Lloyd “Pete” Bucher, of the hostile North Korean action, a grave miscalculation that had horrendous repercussions for the tiny ship’s crew, operating alone and unsupported in hostile waters. Bucher later wrote that, had he known of the commando attack, he would have immediately moved Pueblo 30 miles out to sea, where the enemy’s sub chasers and torpedo boats probably would not have ventured. The crisis might have been averted.

The AGER Program

During the Cold War the United States maintained an extensive intelligence-collecting effort aimed at communist countries within the Sino-Soviet sphere of influence. The Soviet Union, for its part, developed a program of ocean-going trawlers outfitted as electronic surveillance platforms. Throughout the 1960s, these trawlers trailed ships of the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet, inserted themselves into the center of U.S. fleet exercises, and operated in the open just outside U.S. territorial waters intercepting electronic communications.

The United States depended on aircraft, submarines, and low-altitude earth-orbiting satellites to provide a good portion of the intelligence efforts directed at communist countries; the flaw with these collection assets was their inability to remain on station for long periods of time. Looking at the apparent success of Soviet trawler operations, the Navy in conjunction with the NSA began development of the Auxiliary General Environmental Research (AGER) program to provide platforms that could remain inconspicuously on station for extended periods of time.

AGER ships were conceived as small, unarmed or lightly armed intelligence ships. Manned by U.S. Navy crews, communications technicians from the Naval Security Group, and civilian oceanographers, they would provide an equivalent capability to Soviet trawlers as well as be less costly to convert and operate. The United States already had a series of World War II-era Liberty-class ships serving as intelligence platforms; the USS Liberty (AGTR-5) was a member of this series and was a success at its primary intelligence missions, but it was large and costly to operate.

A smaller ship that appeared nonconfrontational in nature might be able to remain on station longer and receive less attention than a large or heavily armed craft. To test the theory, one light auxiliary cargo vessel was selected for conversion; it was refitted and christened USS Banner (AGER-1). During her operations in 1967-1968 off the coasts of the Soviet Union and China and the west coast of North Korea, Banner’s efforts were considered successful, and the Navy was authorized to convert two more auxiliary vessels into AGERs. These ships became the USS Pueblo (AGER-2) and USS Palm Beach (AGER-3). Pueblo was slated to join Banner in the western Pacific.

Hazardous Mission for the Aging USS Pueblo

The ship that became Pueblo was built in 1944 as U.S. Army cargo vessel FP-344; at 850 tons she was used as a general-purpose supply vessel during World War II and the Korean War. Laid up in 1954, she remained inactive until April 1966, when she was transferred to the U.S. Navy and renamed Pueblo (AGER-2), after which she began a lengthy conversion at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington, for her new role as an intelligence platform. After training operations off the western coast of the United States, Pueblo departed for the Far East in November 1967 with a first-time captain and an inexperienced crew. While in Pearl Harbor and at Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan, the ship needed additional repairs, especially of her antiquated steering engine, which had failed 180 times in three days during pre-mission trials in San Diego.

While Pueblo was docked in Japan, Bucher asked his boss, Rear Admiral Frank Johnson, for TNT charges with which to scuttle the ship in an emergency. He was offered thermite instead, which Bucher refused, knowing it to be extremely hazardous as well as against naval regulations. Bucher didn’t pursue the matter, he wrote later, because he didn’t want his superiors to think they had a commander who was obsessed with blowing up his own ship. Pueblo was crammed with highly classified material and equipment, yet possessed only rudimentary equipment for destroying her secrets in an emergency. Bucher requested installation of an emergency destruct system but was refused—it was too costly, superiors said.

After the tragic and deadly attack upon Liberty by Israeli air and naval forces in June 1967, during the Six-Day War, the American chief of naval operations declared that all spy ships, no matter their size, would be armed immediately. Pueblo was authorized to carry a relatively large 50-mm cannon. But, overburdened with men and equipment, the vessel had neither the deck space nor qualified gunners to man the heavy weapon. Instead, Pueblo was supplied with two Browning .50-caliber machine guns, which were mounted on the starboard and stern rails without armor protection and wrapped in cold-weather tarpaulins, the ammunition stored below decks. Admiral Johnson was against arming Pueblo altogether, suggesting to Bucher in December 1967 that he point the covered guns downward or, better yet, store them below deck so as not to appear provocative.

Pueblo was never intended to fight; her protection lay in international law and the freedom of the seas. Like Liberty, Pueblo operated under the assumption that help would be available if needed. The American Seventh Fleet, U.S. forces in Korea, and the Fifth Air Force in Fuchu, Japan, were all informed of Bucher’s mission, but because of the minimal risk assessment, the Navy made no specific requests for emergency support. Brig. Gen. John Harrell, Air Force commander in South Korea, asked the Navy if planes should be kept on “strip alert” for a possible rescue operation, but the Navy declined. When Fifth Air Force personnel questioned the lack of request for strip alert statue for Pueblo, they were also informed that it wouldn’t be needed. All requests by Bucher to upgrade his mission assessment to “hazardous” likewise were refused.

The Capture of the Pueblo

On the afternoon of January 20, 1968, a North Korean SO-1 class Soviet-style sub chaser passed within 4,000 yards of Pueblo. Two days later, two North Korean fishing trawlers passed within 30 yards of Pueblo. That same day, a 31-man North Korean commando team infiltrated across the Demilitarized Zone that separates the two Koreas and attempted to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee and other senior government officials, penetrating as far as the presidential grounds before being halted. Oddly, Bucher and the men on Pueblo were not informed of the commando attack.

Pueblo’s final day of monitoring, January 23, began uneventfully. Early in the afternoon, a North Korean patrol vessel was spotted advancing toward Pueblo at high speed, and as it drew nearer it raised signal flags, demanding Pueblo identify her nationality. The intercepting crew was at battle stations. While his men hoisted three American flags, Bucher verified by radar that his ship was in international waters, farther than 13 nautical miles from shore. As three more North Korean torpedo boats approached, the sub chaser signaled the alarming message that sealed the fate of Bucher and his crew: “HEAVE TO OR I WILL FIRE.”

As two Soviet-made North Korean MiG fighters buzzed Pueblo and two more patrol boats appeared, Bucher made for the open sea, avoiding one North Korean boarding attempt. The aging cargo ship could muster only 12 knots, however, and was quickly caught and surrounded. Bucher’s distress call reached the Naval Security Group in Japan, and he was promised fighter support.

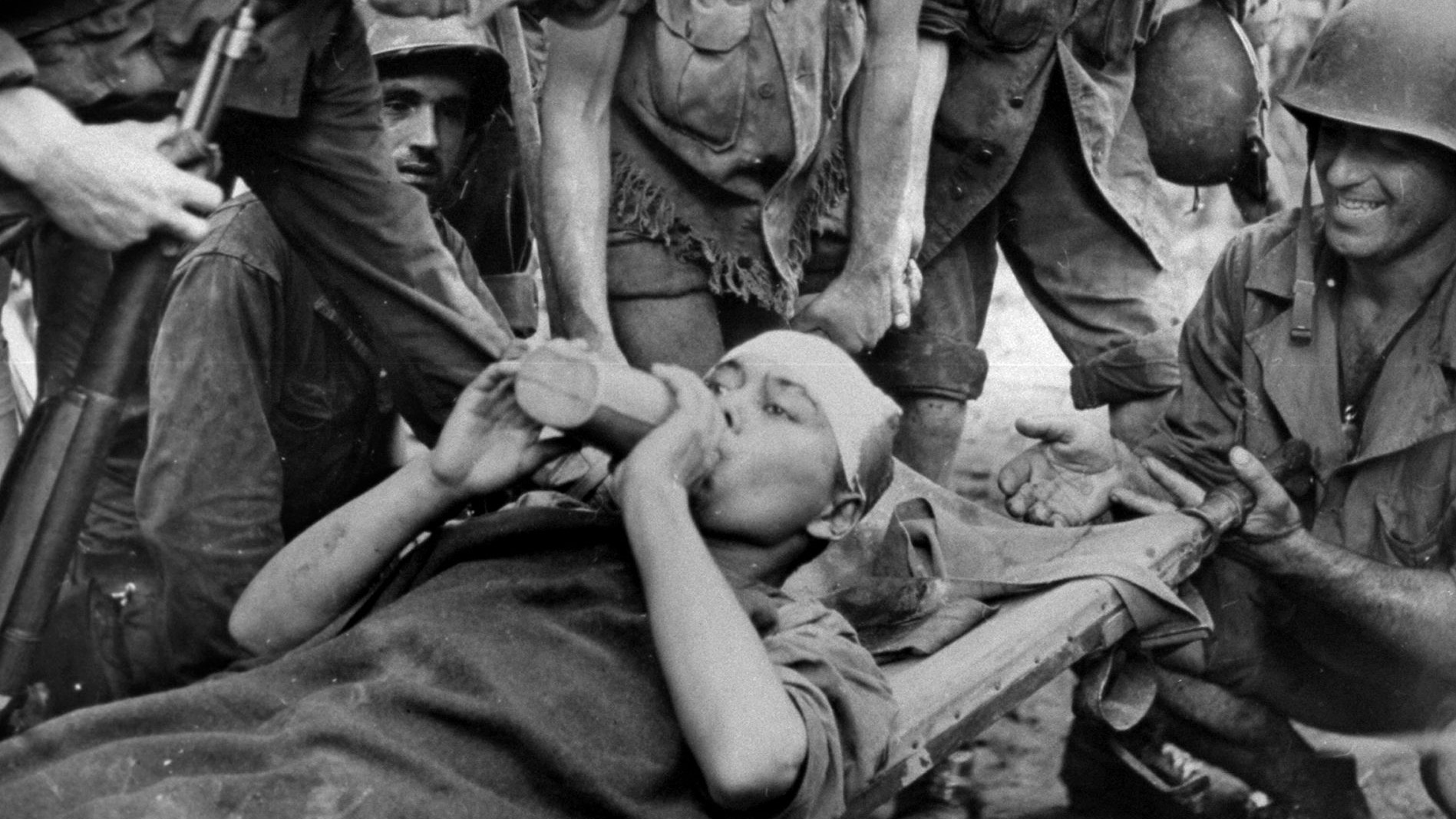

A hail of .57-mm explosive cannon rounds and machine-gun fire from the smaller, faster North Korean patrol vessels rocked Pueblo, and in minutes the tiny spy ship’s maiden voyage came to a terrifying and abrupt end. After eight high-explosive cannon shells penetrated Pueblo’s superstructure, leaving her leaking and damaged and with several crew members wounded, all that was left was an undefended ship with no hope of escaping to the open sea. Bucher gave the order to begin emergency destruction, but the crew found that their sledgehammers and axes had trouble penetrating the metal-encased electronic equipment. Adding to the difficulty, the ship’s incinerators and shredders were inadequate to destroy the enormous amount of classified material that remained on board. Finally, under fire, the crew resorted to throwing classified material overboard.

Pueblo was taken into port at Wonsan and the crew transferred to POW camps, where they were regularly starved, deprived of medical attention, and tortured. Bucher was put through a mock firing squad in an unsuccessful effort to make him confess. Only after the North Koreans threatened to execute his men in front of him did he relent. Finally, following an apology, a written admission by the United States that Pueblo had been spying (later recanted), and an assurance that the United States would not spy in the future, North Korea released the 82 remaining crew members on December 23, 1968, exactly 11 months after their capture.

A Massive Intelligence Coup

The loss of Pueblo was an intelligence failure of enormous proportions. One intelligence estimate concluded that the Soviet Union had gained between three and five years on the United States in the ongoing race for state-of-the-art communications technology. Just hours after Pueblo arrived at Wonsan harbor, a North Korean aircraft flew from Pyongyang to Moscow, carrying between 800 and 1,000 pounds of cargo salvaged from Pueblo. Among the many items lost were a detailed account of top-secret U.S. intelligence objectives for the Pacific, classified communications manuals, a number of vital NSA machines and the manuals that detailed their operation and repair, and the NSA’s Electronic Order of Battle for the Far East. Also lost were information on American electronic countermeasures, radar classification instructions, and various secret codes and Navy transmission procedures. An NSA report described the loss as “a major intelligence coup without parallel in modern history.”

The loss of Liberty and Pueblo within 18 months of each other made it clear how poorly such ships could be defended and how vulnerable their highly secret listening equipment was. Providing adequate protection to ships like Pueblo would greatly increase the costs of an already expensive program. The ships were summarily removed from service and the program dismantled.

The premature end of the Navy’s intelligence collection ships was deeply felt in the intelligence community—spy ships could do a lot that other platforms could not. Beyond direct support to local commanders and national authorities, the ships had the capacity to locate, collect, and report sophisticated foreign electromagnetic signals to the national database of known characteristics of electronic emitters. Such knowledge could aid in development of electronic warfare countermeasures. While other platforms could do much of this work, probably no other vehicle could do it as well. Certainly, no other sensor could cover a target as thoroughly as Pueblo had done.

“There’s Plenty of Blame to Go Around”

A formal Navy court of inquiry used Bucher as a scapegoat to cover up the fact that the military and intelligence community had sent his ship—an aging, leaky, refurbished cargo ship, top-heavy with men and equipment, poorly armed, and barely seaworthy—into hostile waters without adequate protection or contingency plans for emergencies and without the means to destroy classified material and equipment on board. With the odds stacked overwhelmingly against her, Pueblo’s chances for a safe and successful maiden voyage turned out to be very slim indeed.

Despite the preceding spate of hostile North Korean actions, no American fighter aircraft stationed in South Korea, Japan, or on a nearby carrier, USS Enterprise, in the Sea of Japan was put on alert status. One of the admirals who served on the court of inquiry said disingenuously, “There’s plenty of blame to go around.” But South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond put it more succinctly. “Sending poorly armed surface reconnaissance ships into dangerous waters without air cover, naval escort, or emergency plans for adequate support was a serious error in judgment,” Thurmond said. He was right.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments