By Peter Kross

By the spring of 1945, Hitler’s thousand year Reich had come crashing down in flames. The Allied armies that had landed at Normandy almost one year earlier had penetrated deep inside Germany. Soviet forces were shelling the city, and by April, Adolf Hitler, situated in his fortress bunker, would commit suicide.

Throughout Europe, plans were underway by various high-ranking German officers to save themselves. Many planned to make their getaways with the plunder taken from millions of holocaust victims, who had perished in the concentration camps and that which had been confiscated in occupied countries.

In Hungary, a clandestine plot was hatched by a few greedy military officials who took possession of millions of dollars worth of gold, diamonds, and other precious valuables stolen from the Jewish victims of the holocaust. So began the myth of the Hungarian Gold Train, one of the most mysterious and brazen incidents to come out of World War II.

The Jews of Hungary occupied a unique position among the nations of Eastern Europe. In 1867, the Hungarian government emancipated the Jews, who then began organizing their cultural and economic life as a distinct minority in a non-Jewish nation. The Catholic Church never recognized the Jews’ distinct position in everyday life and only gave lip service to their newly found freedom.

In 1938, one year before the outbreak of World War II, the first anti-Jewish laws were put into effect in Hungary. The government of Kalman Daranyi decreed that all professional Jews, such as doctors and lawyers, could no longer pursue their livelihoods. Further restrictions forbade Jews from participating in the cultural arts of the country. In 1939, the so-called Second Jewish Law put severe impediments on the everyday occupations of the majority of Hungary’s Jews. For the Jews of Hungary, conditions became even worse when the radical, anti-Semitic Magyar government allowed the Nazis to assert control over their country at the outbreak of World War II.

Hitler’s Final Solution to the Jewish problem in Europe did not spare Hungary’s minorities. Under the command of Colonel Adolf Eichmann, over 600,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to the concentration camps. Before being killed, the Nazis stripped these innocent victims of all their precious jewels, gold, furs, and anything of value that could be later sold for profit.

Toldi Develops Plot to Smuggle Valuables Out of Hungary

By the end of the war, 200,000 Hungarian Jews remained alive. Like their brethren, they too had lost their jobs and possessions, taken by either the puppet Magyar government or its Nazi protectors. The fascist government of Hungary was in possession of millions of dollars worth of valuables looted from its own populace. As the war drew to an end, Hungarian government officials drew up an audacious plan to take these valuables out of the country and far from the reach of the fast approaching Allied armies.

When Hungary fell to the Red Army on April 5, 1944, preparations to move the treasure went into high gear. With Switzerland as its final destination, a large train consisting of 24 cars filled with the looted treasure, 15 other cars containing police and selected army officers, a large amount of foodstuffs, and finally, seven cars containing miners, made emergency plans to leave. In all, the train consisted of 46 cars, with a total of 213 people on board. The gold train was about to begin its journey into myth and legend.

The man in charge of the gold train was Colonel Arpad Toldi. Toldi had served in the German ministry of occupation in Hungary. He had written numerous pamphlets on police procedure and a manual for the Gendarmerie (police) training school. Soon after the German occupation, he had been appointed governor of the Fejer district in Hungary. Toldi was virulently anti-Semitic and anti-Soviet in his politics. He appointed his own people to all the local positions of governmental authority, enforced the deportations of Jews, and oversaw the seizure of their personal property. He was eventually given the prestigious job of Commissioner of Jewish Affairs.

With Soviet troops now on his heels, Toldi began the laborious process of getting the gold train ready for departure. He firmly believed that the treasure was the property of the Hungarian government.

Hundreds of men toiled for months during the summer, fall, and winter of 1944 to prepare the stolen property for its journey. Under his personal supervision, Toldi divided the most precious cargo in preparation for two types of transportation. The most valuable goods, mainly gold and jewels, were stored on trucks. The rest of the booty was attached to the main part of the train. The cargo was divided to save some of the items in case the train came under Allied aerial attack.

The Gold Train Begins Its Journey

By the end of December 1944, the gold train was ready for departure. On board were members of Toldi’s family, including his wife, son, and step daughters. At a point along the train’s trek, Toldi was reported to have unceremoniously expelled his step daughters from the caravan.

The gold train began its journey shortly before Christmas 1944. Its first stop was the town of Zire, 120 miles from Budapest. At this juncture, Toldi requisitioned several transports from a nearby Hungarian army base to gather up more Jewish gold and jewels, which had been secretly kept at the nearby Obanya Castle. A week later, the train arrived in Brennbergbanya. It stopped along the route at various small towns and villages where more gold and other valuables had been stored in warehouses and were then transferred to the train.

The gold train spent 92 days at Brennbergbanya, where the cargo was carefully counted and sorted into various categories. Classifications included precious stones and jewelry, gold objects, gold coins, gold watches, silver objects, and furs.

Toldi Tries to Escape into Switzerland

By the time the gold train began the second leg of its journey in the spring of 1945, the war was almost over. Toldi was convinced that the Soviets were actively hunting his treasure-laden train, and he began a desperate gamble to keep the contents out of their hands. As the train neared the Swiss border, Toldi intended to stop from time to time and begin selling off some of the contents to the guards on board, as well as certain civilians living along the route.

Events on the train were about to shift into high gear as Toldi began a double cross intended to ensure the safety of himself and his family at the expense of the rest of the crew and passengers of the gold train.

During the night of March 30, 1945, Toldi, his family, and a few trusted aides left the train with the most valuable of the loot, leaving his subordinate, Lazlo Avar, to take the train to its ultimate destination, the Swiss-Austrian border. This was a tactical decision, Toldi stated to Avar; he would meet up with him later. Unknown to Avar, Red Army units were only 10 miles away.

At the beginning of April 1945, with the end of the war in Europe now weeks away, Toldi and his family were situated at the border between Switzerland and Austria where they accumulated additional valuables beyond what they had already stolen from the train. Toldi and his party tried to enter Switzerland but were refused admission by the Swiss government. With his situation growing more desperate by the day, Toldi had to find a way into Switzerland before the Soviets could grab him. He now turned to an SS officer, Wilhelm Hottl, for help.

Hottl had previously been a high-ranking officer in the Balkans, and the two men had come in contact with each other during their work. At this point, the historical record becomes sketchy regarding how much and what kind of assistance Hottl gave Toldi, as well as what the former Nazi officer demanded in return. Reports say that Toldi gave Hottl 10 percent of the plunder in exchange for his promise to transport the fugitives to Switzerland and to give the Toldi family fake German passports under assumed names.

Hottl worked with another con man, Friedrich Westen, an Austrian who traveled freely to Poland, Romania, Italy, and Yugoslavia. In February 1945, Westen made secret contact with Allen Dulles, the American OSS station chief in Bern. Westen, it seems, was a go-between on behalf of Hottl with the OSS. In time, however, the OSS worked directly with Hottl, although the extent of their cooperation is not known.

Toldi, the story goes, got false passports from Westen. In return, Hottl and Westen received four crates of valuables as their cut. By May 1945, Hottl and Westen disappeared from sight. Their trail had grown cold—at least temporarily.

After the war, the new Hungarian government tried to find Toldi, and investigators came up with interesting information. Toldi’s personal file was missing from the Hungarian Ministry of Defense. Reports placed him in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1947, but that sighting could not be verified. Charges were filed against him for the forcible deportation of 4,000 Hungarian Jews, and the post-war government asked for his extradition. All requests for his surrender were for naught. Unconfirmed accounts placed Toldi in North Africa or as having enlisted in the French Foreign Legion.

The Train is Tracked Down in Werfen

By May 1945, U.S. intelligence operatives actually made contact with the gold train. On May 16, the train arrived in the city of Werfen and stayed there four weeks. During this time, U.S. Army investigators began interrogating the remaining members of the train entourage and soon learned its sordid history. At the same time, the Soviets took control of Hungary and demanded that all the loot on the train be turned over to them. With the Soviets in the picture, an international incident loomed ahead.

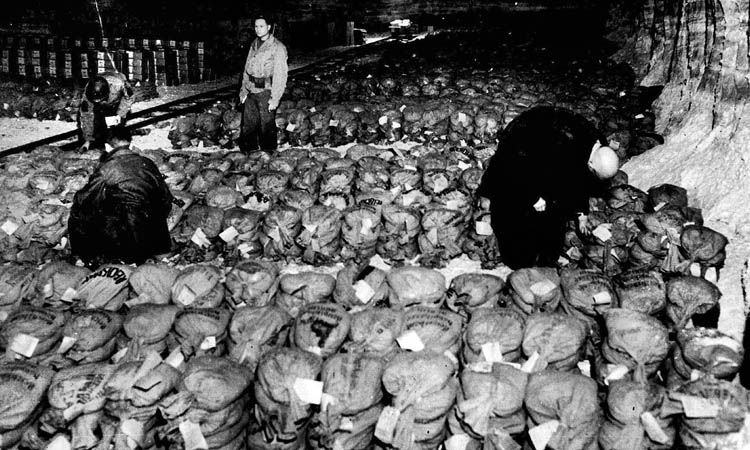

The first members of the American military to question the Hungarians on the train were the members of the 430th Detachment of the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) stationed in Salzburg, Austria. Marton Himler was the arresting officer who took charge of the gold train investigation. With the train now in American hands, it was given a new name—the “Werfen Train.” The train and its passengers were separated, and the Hungarian guards helped the Americans unload and sort the contents. Emptied from the train were 1,500 crates containing watches, silverware, and jewelry, as well as 5,200 Persian carpets, stamp collections, and fine china.

No immediate provisions were made for the return of the train’s contents to the people of Hungary. Three years later, on July 27, 1948, Secretary of State George C. Marshall sent a cable to the U.S. Legation in Budapest spelling out the United States’ position regarding the contents of the gold train. Marshall’s directive reads in part: “American forces having examined the portion of the Hungarian train in the American Zone of Austria, the U.S. Commander (General Mark Clark) determined that the contents therefore were unidentifiable as to owners and, in view of the territorial changes in Hungary, as to national origin, restitution to Hungary being therefore not feasible, it was determined, with the approval of this government, that the property in question would be given to the Intergovernmental Committee for Refugees …”

This statement by Secretary Marshall made an already complicated situation more involved as the surviving Hungarian Jewish population railed at the American decision, asserting that the contents of the gold train belonged to them.

American Officers Also Guilty of Taking Confiscated Valuables

Greed on the part of certain high ranking American military officers also reared its ugly head. On July 13, 1945, Maj. Gen. Henry Collins, the commander of the 42nd Infantry Division in western Austria, requisitioned certain valuable objects from the gold train for his own personal use. Among the items taken by General Collins for both his private villa and his personal railcar were the following: chinaware; silverware; glassware, including liqueur and champagne glasses; five rugs; eight paintings, 30 sets of table linens; 60 sheets; 60 pillow cases; and 60 large bath towels. Other highranking American officers also took gold train items. Some items from the train unexpectedly showed up at American PX stores where they were sold to GIs and others.

Post-war documents held in the Central Zionist Archives (CZA) in Jerusalem reveal the extent of the American pillage of the gold train. Dated July 16, 1947, a report by Yehuda Gaulan, a member of the negotiating team with the Americans regarding the fate of the gold train, is quite revealing.

“The local American authorities are doing everything to obstruct that work,” the report reads, “especially in view of the fact that at the beginning of this work they have lost a source for easily acquiring riches. It is known that top ranking officers of the American army have pocketed very valuable items …”

The Americans were not the only ones to take illegal possession of gold train contents. French troops, tipped off by informers, were able to confiscate large caches which had been hidden in their occupation zone in Austria.

By 1948, portions of the receipts from the sale of contents of the gold train found their way into private hands. Some funds wound up in the vaults of the Hungarian National Bank. About $8 million was sent to the Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem.

With the U.S. declaration that the rightful owners of the gold could not be ascertained, large amounts of the gold train booty were shipped to the United States for auction. The first shipment of merchandise arrived in New York in December 1947, under the direction of the Advisory Liquidation Committee, and was auctioned in June 1948, at the Parke-Bernet Galleries. Roughly $4 million in valuables was put up for auction.

In December 1949, over a thousand paintings were transferred to the custody of the government of Austria. In a change of direction by the American government, a March 26, 1952, State Department document titled Confidential Security Information: Hungarian Cultural Property in U.S. Custody, said in part that it would “… propose that all cultural property of Hungarian ownership will be held indefinitely for eventual return to the rightful owners and that this fact should be broadcast to Hungary.”

Toldi is Finally Brought to Justice

The strange case of the Hungarian gold train lingered well after the end of World War II. Wilhelm Hottl turned himself in to U.S. 3rd Army personnel along with six of his men. The Army’s Counterintelligence Corps issued a most wanted list with the name of Arpad Toldi right at the top for the crime of “destruction of Hungarian Jewry.” Toldi, aware that he was a wanted man, made contact with a French Army officer named Colonel Henri Jung and told him a bogus story that he was ordered to “protect” the gold train from the Soviets. He provided Jung with the locations of various sites in the French zone that contained portions of the gold train loot. Toldi decided it was in his best interest not to reveal his secret deal with Friedrich Westen and Wilhelm Hottl. Toldi was finally arrested in August 1945, and released from confinement that November with no charges being filed.

In October 1999, the United States government released its findings on the gold train incident as part of its investigation into the role of the Swiss government during the war. The U.S. report’s ending paragraph sums up the case in spades. “In the end, there may be no single explanation of why the property of the Hungarian Jewish community was so readily dispersed. But the fact remains that the application of several policies to the various assets aboard the Gold Train assured that the property was never returned to its rightful owners.”

Peter Kross is the author of The Encyclopedia of World War 2 Spies. He resides in New Jersey.

Good article. I highly recommend watching the movie ‘The Lady in Gold’ with Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. It details the attempts to return a famous painting solen by the Nazies to a surviror of the family from whom it was stolen. The official storyline is below:

Storyline

Maria Altmann (Dame Helen Mirren) sought to regain a world famous painting of her aunt plundered by the Nazis during World War II. She did so not just to regain what was rightfully hers, but also to obtain some measure of justice for the death, destruction, and massive art theft perpetrated by the Nazis. Written by Elyse J. Factor

Yes – that great film “woman in gold” about the Gustave Klimt painting was so interesting! I’ve have watched it twice.

The “monuments men” is another great film about the recovery of a multitude of art & sculpture stolen by the nazis.

So Toldi got away & was never brought to justice?