By William McPeak

When did humanity begin throwing explosive devices? What are the origins of the modern grenade, and how did explosives evolve?

By the early 13th century, the Chinese and the heirs to their technology, the Mongols, were using effective incendiaries such as fire arrows and small rockets in battle, and further advanced to using metal casings for larger incendiary grenades. Meanwhile, in Muslim Spain, the military use of explosive gunpowder was typical by the middle of the century. Spanish Moors were hurling rocks with explosive gunpowder from primitive bucket cannons in siege warfare about the time the Mongols were using them.

Gunpowder: From a Propellant to a Weapon

By the early 14th century, European cannons, although not yet completely replacing the age-old slinging siege machines such as the catapult and trebuchet, were evolving quickly into cheaper, more rapid-fire weapons. By the time the idea of using gunpowder as an explosive weapon rather than as an explosive propellant for cannons and early firearms, it was near the end of the 15th century. The innovation was a simple discovery—gunpowder was transported in barrels, and flammable powder dust near camp flames or cannon matches caused occasional massive explosions. But it was not until 1495, when Francesco di Giorgio Martini, a Sienna architect, loaded barrels of powder into a shaft beneath Castel Nuovo in Naples, lit a long match, and proceeded to blow up a whole section of wall and scores of French defenders, that the true destructive potential of gunpowder was realized.

The mine—in the form of a powder keg—quickly became an accepted weapon and continued to evolve into more manageable sizes such as the compact petard mine attached to gates and walls. The earliest innovators may have been the Knights Hospitalers of St. John, the crusading order in the Middle East. Vastly outnumbered, the Hospitalers needed up-to-date military technology for their survival, and for that reason they began adapting and modifying the use of gunpowder in the later 15th century. The Knights used terra-cotta to fashion hand-sized ovoid or heart-shaped containers four inches in length and filled with Greek fire. They etched crisscross lines for better gripping, thus anticipating the modern grenade with its pineapple design for grip and fragmentation.

In the early 16th century, the Knights made a variation of these “fire pots” using gunpowder. The neck of the new weapon was covered in canvas or parchment and wound with a match cord looped into the container, with both ends wound around the neck and lit to ensure detonation. These hand bombs proved to be very effective as antipersonnel weapons. Dropping firearm shot into the mixture was a natural progression, since grapeshot had been used for cannons for over a century. This was the first instance of the explosive hand grenade.

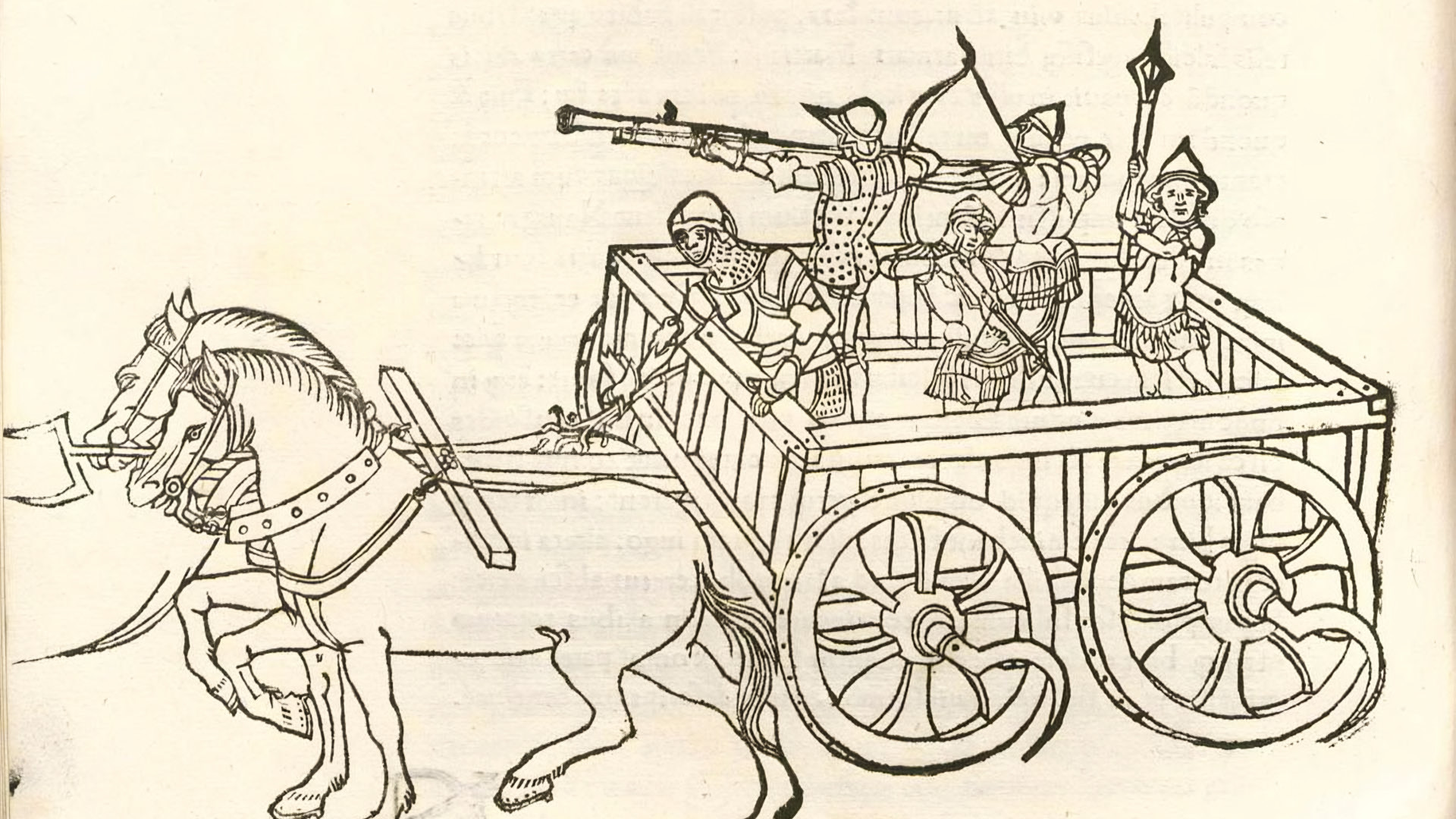

Explosive cannonballs with a fuse appeared in the later 16th century, adapted from the development of similar-sized bombs that could be fuse-lit and launched by small catapults, slings, and heavy-duty crossbows. Explosive and incendiary devices continued to be adapted for siege use in the 17th century. Hand-held sizes also continued to develop with the use of various metal casings, some entwined in rope with a leader to sling the grenade. Another variation was the spiked grenade, which alleviated the danger to volunteers planting petards on wooden ramparts. The spiked grenade, embedded with as many as 80 or 90 iron spikes, was launched by crossbow and could stick to anything wooden—a precisely aimed weapon that saved the lives of many besiegers, if not those besieged.

The Evolution of the Hand Bomb

Toward the end of the 16th century, soldiers realized that hand bombs or grenades could be effective in battlefield conditions. For more than a hundred years, large center and flank formations had been divided into specialized infantry and cavalry block formations. Thrown with sufficient skill, a grenade could wreak havoc on these formations and cause enough damage to inspire panic and retreat. Such weapons needed strong fellows with good arms. By the mid-17th century, soldiers with these specific physical abilities, “grenadiers,” were formed as companies within infantry regiments. As special soldiers more vulnerable to enemy fire, they were given more pay and various privileges, including distinctive uniforms and hats. In the 18th century, with the formation of the midsize battalion unit, England, France, and Prussia began taking grenadier companies from individual regiments to form special battalions. Napoleon Bonaparte thought enough of their service to form brigade- and division-level units of grenadiers. By the mid-19th century, the use of grenadiers went out of military fashion, although units kept the name as a traditional title for special skills and esprit de corps.

Troops in the field continued to improvise their own grenades. During the Crimean War, grenades made from powder and nail-packed soda bottles were devised by the British and thrown into Russian trenches. Grenades were a factor during the Russo-Japanese War. German observers noted the use of grenades and began turning out various types—disk-, ball-, and egg-shaped—for stockpiling, using a high explosive developed in Germany in 1863—TNT. During World War I, there were some 50 new designs—good and bad—developed for grenades with two basic ignition types: the time fuse and the more dangerous impact or percussion design. The latter was potentially unsafe because it exploded on impact—but impact could come from being jarred in many different ways before ever getting close to the enemy. For obvious reasons, timed grenades were preferred over the percussion variety.

The Birth of the Modern Grenade

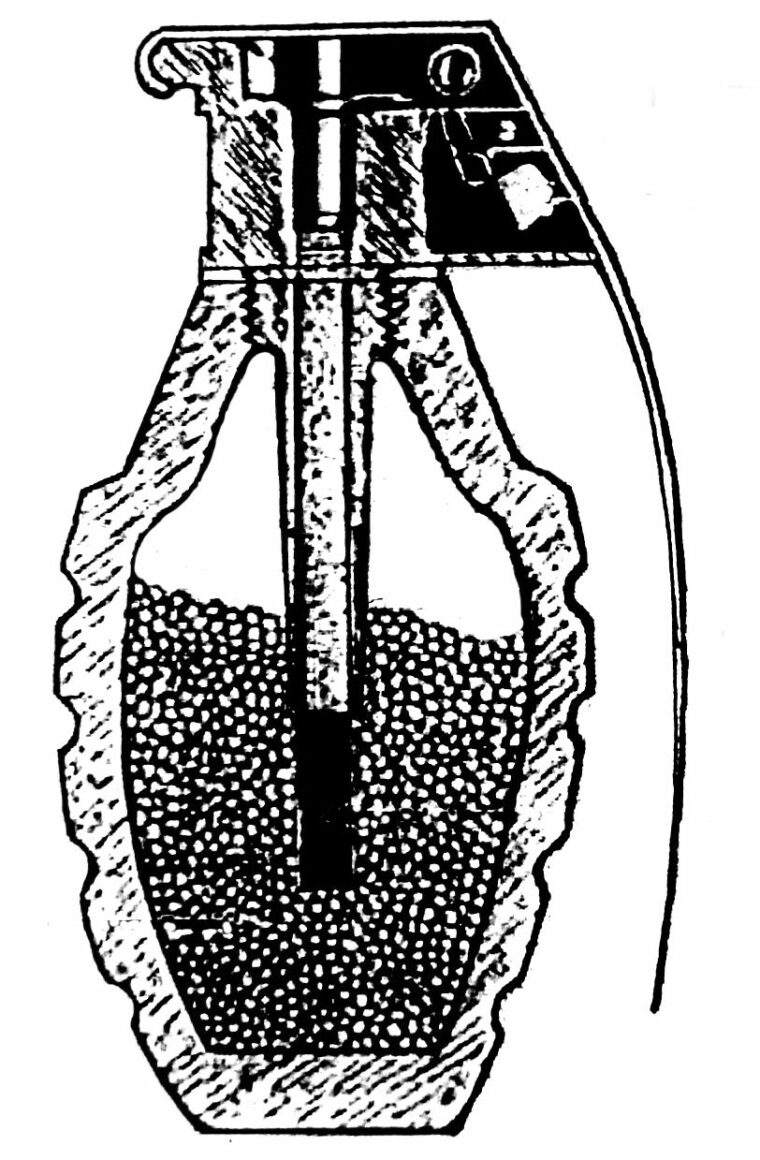

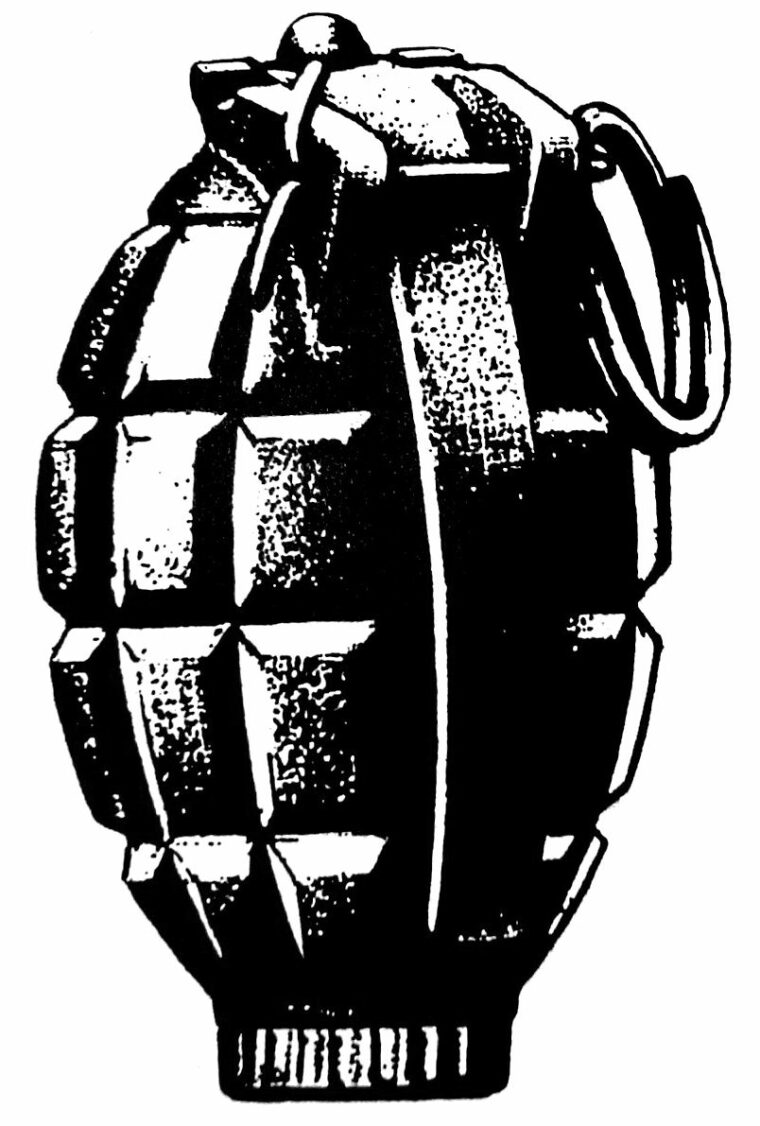

The first modern grenade was the British Mills bomb, developed in 1915. With a cast-iron casing ribbed horizontally and vertically to form surface notches, it was the first of the so-called “pineapple” or fragmentation grenades. The Mills bomb employed a central spring-loaded firing pin and spring-loaded lever. The lever released the striker, which in turn ignited a four-second fuse. Although it was filled with low-explosive gunpowder, the Mills bomb nevertheless was a leap forward in grenade technology. Other designs would prove more enduring. The German variation of the stick grenade appeared in 1915 and was perfected by 1917. This was the famous “potato masher,” Model 24, with a time fuse lit by a friction igniter that was used throughout World Wars I and II. It had the advantage of achieving about twice the throw distance of conventional ovoid-type grenades because of the torque achieved with the hollow wooden handle, which also contained a pull fuse.

The United States entered World War I with a complicated impact fuse grenade that proved such a failure in combat that it had to be scrapped. For a short period, the French pineapple grenade, the F-1, was used by American forces, but in 1917 an improved variation of the Mills bomb, the Billant grenade fuse system, was integrated into a new American grenade, the famous pineapple MK. The MK-1 was abandoned after May 1918 for the MK-2, which was improved after the war and used in World War II and Korea. New design and safety features went into the improved M-61 used in Viet Nam and today’s M-67.

Different Kinds of Grenades

Grenade design was not confined to the ignition mechanism; it also entailed the combat use of the weapon. The most common defensive grenade was the fragmentation grenade, which was meant to throw shrapnel out to about 50 yards. The Mills bomb and other pineapple designs were of this type. An offensive grenade was meant for demolition, and thus was packed with more explosive. The highly explosive potato masher was an example of the offensive grenade. Another type was the concussion grenade, designed to have the effect of a shockwave in an enclosed area. The concussion grenade used a thinner, low-fragmentation casing, and its explosive power was concentrated within a 10-yard radius.

The idea of using gas in grenades originated with the French, who first used tear gas (an eye- and throat-burning, chlorine-based compound) against the Germans in 1914. The proliferation in the use of poison gases during the war inevitably found an application in grenades as well. The Germans developed gas grenades loaded with various poison gases in liquid form. The small egg grenade was often used for this because its aerodynamics allowed a longer throw. The Allies were quick to follow up with their own gas grenades. Because shifting winds could easily blow the gas back on the attacker, gas masks became essential equipment.

Grenade Tactics of World War I and II

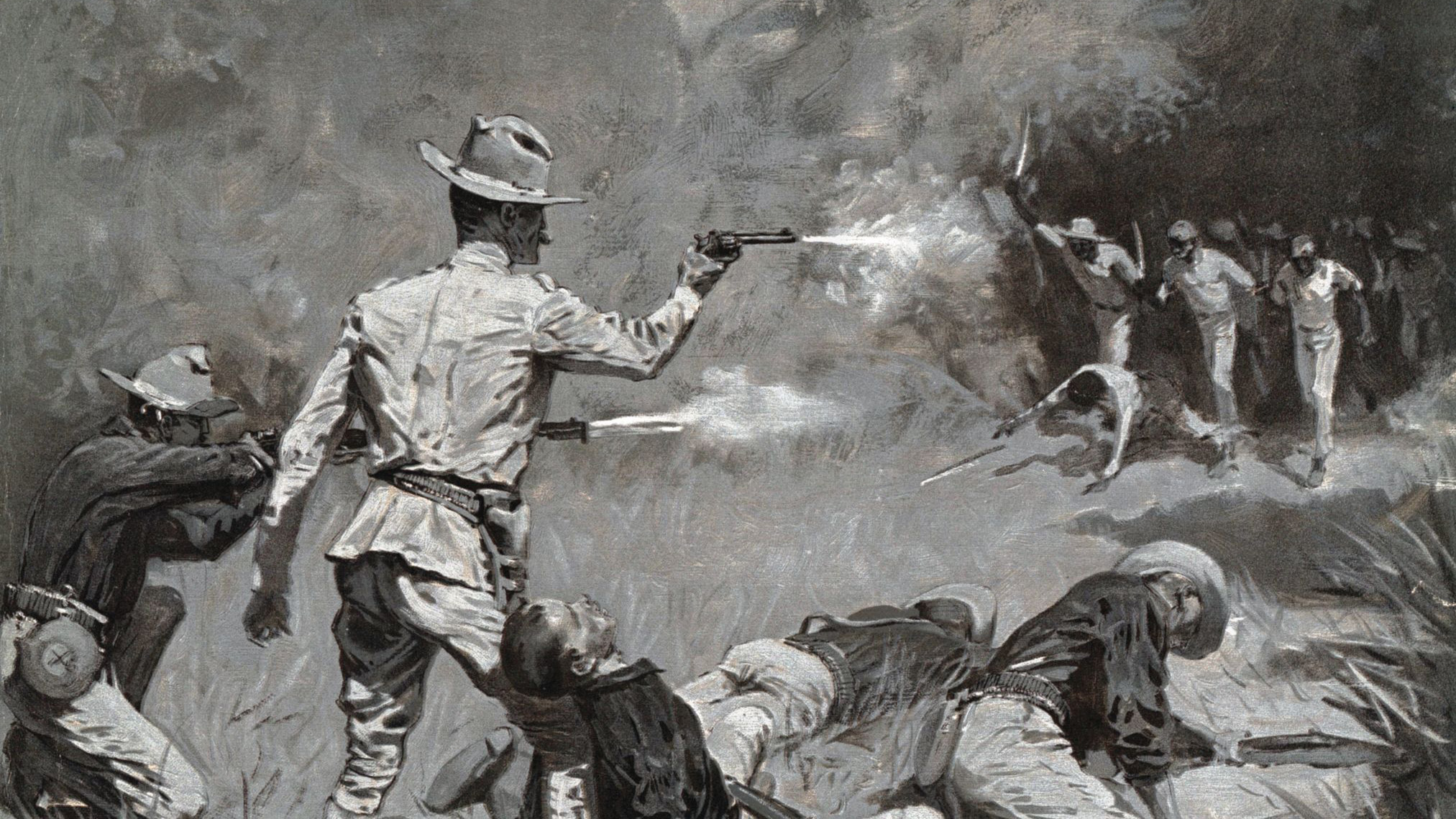

Tactically, the grenade came into its own in World War I, where stalemated trench warfare was a fact of life and lobbing a grenade into the enemy’s trenches might cause more casualties than random pot shots from trench to trench. Throwing grenades became fundamental field tactics, and skirmishes between grenade-throwing patrols became commonplace. The grenadier was reconstituted into bombing parties used by both sides to raid the enemy trenches and cause disorganization and panic before an infantry assault. The longest grenade combat encounter during World War I occurred at Pozieres Heights on the night of July 26-27, 1916, when Australian and British troops fought the Germans for 121/2 hours. The Germans used every kind of grenade they possessed, while the Allies used some 15,000 Mills bombs.

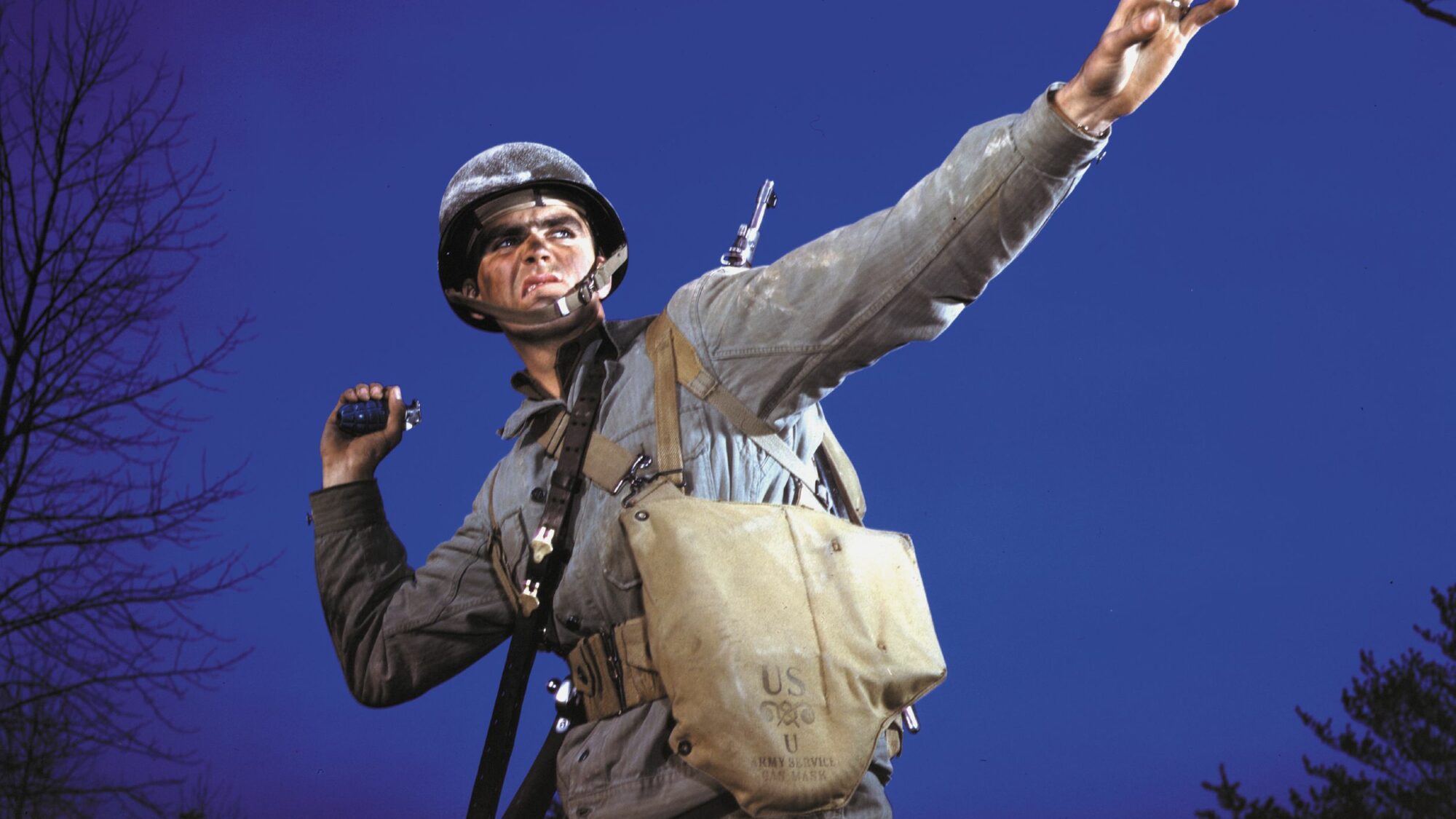

By World War II, it was common for most infantrymen to be proficient in the use of grenades, but specialists still were trained for tactical duty in preparing and delivering grenade packs against tanks and machine-gun pillboxes. Lobbing a grenade ever farther was an important incentive for improvements. The idea of using a rifle to do so was first advanced during World War I. A variant Mills bomb was developed with a base plug and rod to fit over the rifle barrel as a launch adapter. Other adapters included a simple tin can-looking affair, a discharger cup, whose base was integrated over the rifle barrel. Launch was via a blank cartridge. By World War II, TNT had been improved with the more powerful RDX (explosive nitroamine) and Composition B, a mixture of the two. (Get more acquainted with the weapons and machines that defined the Second World War inside WWII History magazine.)

The American military developed a tube-launched small rocket and shaped-charge aerodynamic grenade to disable tanks. The latter would become the powerful M-10 grenade, while smaller versions of rifle grenades were adapted for the M-1 Garand rifle and M-1 carbine. With a new stabilized rocket launcher added in late 1942, the weapon became the bazooka rocket grenade, the world’s earliest RPG. The Germans copied the bazooka as the Panzerschreck; the Russians would use it as the basis for what would become the RPG-7, the weapon of choice for modern-day terrorists. There were also launcher adapters for the conventional pineapple grenades, but the user had to pull the grenade pin before seating it for launch. American forces continued to use bazooka rocket grenades through the Korean War.

By World War II, the gas grenade had expanded in other directions. Smoke bombs or smoke grenades were used as nonlethal tactical weapons, usually in canister form, for screening military movements, signaling (using different colored dyes with potassium-based smokes), targeting, and marking landing zones. There were also exploding smoke grenades, using highly flammable and poisonous white phosphorus with a bursting charge to spread more than smoke. These were employed both as antipersonnel agents and for illuminating enemy positions. Along with these were incendiary grenades containing thermite reactants, aluminum metal, and iron oxide; they were used to destroy weapon caches, artillery, and vehicles. Not requiring oxygen, some were also used for underwater demolition. Like other grenades, the incendiary grenades had rifle-mount applications with extra charge-assists to boost effective ranges.

The Grenades of Today

Grenade technology, following functional demand and progression, has continued to inspire improvements. Many military applications have been translated to law-enforcement work. Tear gas grenades are a common example, along with so-called stun or flash grenades used as diversionary weapons to disorient and confuse criminals with intense light and noise. Yet another crossover is the sting grenade, designed to explode with a nonlethal payload of small, hard rubber balls that can incapacitate suspects without killing them.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments