By Gene Eric Salecker

On January 9, 1945, after almost three years, General Douglas MacArthur and the United States Army returned to the Philippine island of Luzon, landing at Lingayen Gulf on the northwest coast. After establishing a fortified beachhead and moving inland a few miles, MacArthur formed two “flying columns” of cavalry, armor, and artillery and ordered them to go toward the Philippine capital of Manila.

“Go to Manila,” he told the column commanders, “go around the Nips, bounce off the Nips, but go to Manila.” Among the objectives for the flying columns was the rescue of civilian internees being held in captivity at Santo Tomas Catholic University and Bilibid Prison inside Manila. On the night of January 31, the columns started forward.

One of MacArthur’s top priorities during the invasion of Luzon was to rescue the men, women, and children being held at four prison camps around the island. The civilians had fallen into the hands of the Japanese during the fall of the Philippines in 1942, and MacArthur wanted to set them free before the Japanese committed any acts of reprisal.

The prison camp near Cabanatuan, holding 500 prisoners of war, was liberated on January 28 in a daring behind-the-lines raid by the 6th Ranger Battalion. The two Manila area compounds, Santo Tomas University, with 4,000 civilian internees, and Bilibid Prison, holding 500 civilians and 800 American and Allied prisoners of war, would be liberated on February 3 and 4, respectively. The fourth internment camp, close to the village of Los Baños near the southern shore of Laguna de Bay, a large inland lake lying southeast of Manila, would be the only one still in existence in the middle of February, but not for long.

On January 21, on the Philippine island of Leyte, south of Luzon, Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, commander of the Eighth Army, met with Maj. Gen. Joseph Swing, commander of the 11th Airborne Division, the only airborne division in the Pacific. During the meeting, Eichelberger informed Swing that his unit of paratroopers and glidermen would be used to form a second front in the battle for Luzon, making a beach landing and a parachute drop south of Manila. Among his objectives, Swing was given two priorities: get to Manila ahead of Sixth Army coming down from the north, and free the prisoners at Los Baños as soon as possible. Although Swing had never heard of the Los Baños prison camp, his staff began gathering information while they got ready for their invasion of Luzon.

The civilian internment camp near Los Baños had been established by the Japanese in December 1942 at the Agricultural College of the University of the Philippines, located about 21/2 miles southeast of the town. Held within the large, fenced compound of more than 30 buildings were 2,147 internees of various nationalities, including 1,575 Americans.

General Swing made a beach landing with his glidermen near the city of Nasugbu, 55 miles south of Manila, on January 31. Three days later, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) dropped on Tagaytay Ridge, along the northern shore of Laguna de Bay, to capture and secure a vital road junction. Almost immediately, General Eichelberger asked Swing to form a flying column and send it south toward Los Baños to rescue the internees.

With his troops heavily engaged with the Japanese forces below Manila, Swing pointed out, “of the 8,000 troops of the division, no flying column of sufficient strength could be made immediately available.” Instead, Swing recommended that the mission be suspended until he could “disengage a force of the necessary size from contact with the Japs.” Over the next few weeks, although the 11th Airborne Division drove steadily northward toward the southern environs of Manila it was eventually beaten to the capital by the Sixth Army. Missing out on Eichelberger’s first priority, Swing then turned to his second priority, the raid on Los Baños.

During the attack toward Manila, Swing’s staff had been gathering intelligence and drawing up plans for the raid on Los Baños, located 40 miles behind Japanese lines. As envisioned, Swing wanted his planners to use both an airborne and amphibious attack. Swing wanted his paratroopers to land near the prison compound and destroy the Japanese garrison while his amphibious force swept across Laguna de Bay equipped with vehicles for transporting the internees to safety. Additionally, Swing felt that a diversionary attack was crucial to draw the Japanese troops away from the camp.

The raid would entail of a four-pronged attack. The 511th PIR Provisional Reconnaissance Platoon under Lieutenant George E. Skau, aided by local guerrillas, would move into an area opposite the camp prior to the strike. Then, simultaneous with a parachute drop of Lieutenant John M. Ringler’s Company B of the 511th PIR and an amphibious landing by Major Henry A. Burgess’s 1st Battalion, minus the airdropped company but reinforced with a platoon from C Company, 127th Airborne Engineer Battalion and two howitzers from Battery D, 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, the recon platoon and guerrillas would eliminate the sentries along the wire.

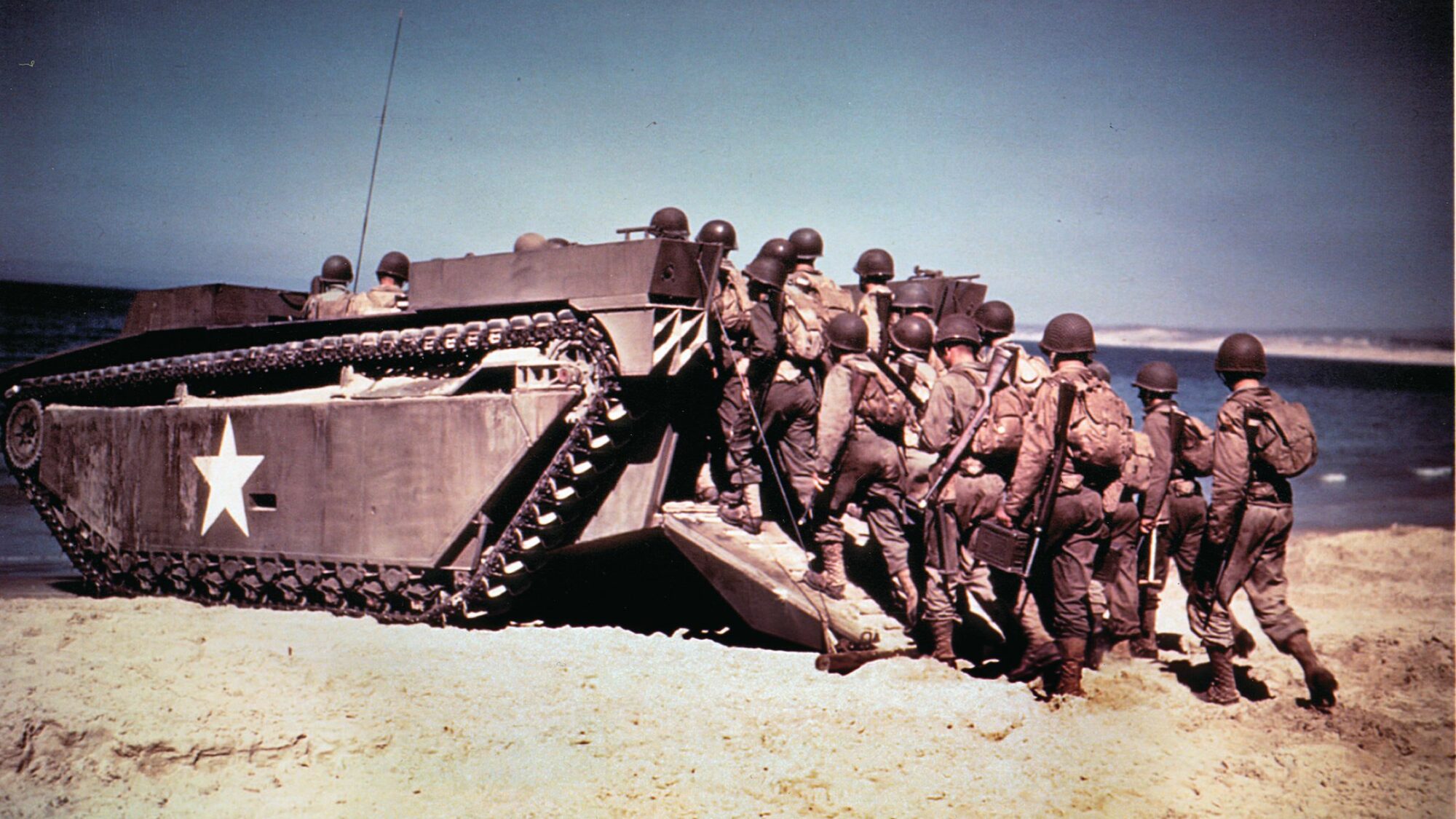

While the amphibious force, landing in LVT-4 amphibious tractors or amtracs of the 672nd Amphibious Tractor Battalion rolled up onto the beach from Laguna de Bay and continued toward the camp, the company of paratroopers would link up with the recon platoon and guerrillas and wipe out the rest of the garrison. When the amphibious force reached the camp, it would deploy to the south and west to block any reaction by the Japanese.

The fourth force would form a flying column composed of the 1st Battalion, 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Ernie LaFlamme, the 675th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, the 472nd Glider Field Artillery Battalion, and Company B of the 637th Tank Destroyer Battalion and move by road around the southwest end of Laguna de Bay up to the gates of the camp. This force, under the command of Lt. Col. Robert H. Soule and designated “Los Baños Force,” would bring enough trucks with it to carry out all the internees and paratroopers. If the fourth group could not reach the camp, the internees could be ferried out in the amtracs across Laguna de Bay while the paratroopers fought their way out. The raid was scheduled for dawn on February 23, 1945, a moonless night.

“Something Big was Brewing for B Company”

Major Burgess pulled his 1st Battalion troops out of line on February 21 and moved them to New Bilibid Prison at Muntinlupa on the northwestern shore of Laguna de Bay. “Something big was brewing for B Company,” remembered Jim Holzem. “We could feel it in the air. And the rumors! Something big, something important, was coming up. What was it all about? We were loaded onto trucks and driven about 20 miles south of Manila. The trucks drove up to the gates of a large penitentiary called New Bilibid Prison, and we were driven in. Some thanks for all the fighting we had been doing! We were being put in prison. We were assigned cells and that night slept on cots with boards for mattresses. I guess the reason we were spirited away to prison was that they wanted to maintain complete secrecy regarding the upcoming operation.”

During the last few days before the raid, a major change was forced upon the planners. Combat engineers looking into the route of the mobile relief force had discovered that a number of bridges between the San Juan River, the jumping off point for the column, and the Los Baños Internment Camp had been demolished by the Japanese and that the road to the camp was in terrible shape. Although the engineers were confident that they could rebuild the bridges and fill in the roads, they admitted that such jobs would take time, too much time. An alternate plan had to be found.

Instead of carrying the internees out in trucks that would accompany the mobile relief force, the plan was changed so that the internees would be carried out in the amtracs, capable of carrying 35 combat infantrymen each. With over 2,000 internees, it would take two trips to carry everyone to safety. The 511th PIR would have to hold the beachhead until everyone was away. Colonel Soule’s ground force, coming from San Juan, was now relegated to a diversionary role rather than a rescue role. One last change had the 511th PIR walking out of Los Baños on foot, heading west and hoping for a quick link-up with the mobile task force.

At 8 pm on February 21, Lieutenant Skau and his 22-man reconnaissance platoon set out for the southern shore of Laguna de Bay. Skau and seven men were the first to go, setting out into favorable winds in a small native fishing boat, or banca, handled by a Filipino crew. Fifteen minutes later, another group of six followed. When the third and largest group was about to set sail in the largest banca, carrying the reconnaissance platoon’s heavy weapons, ammunition, rations, and extra weapons and ammunition for the guerrillas, the Filipino captain informed the men that he had a broken rudder. Two hours later, the third banca finally pushed into the bay, but by now the winds had died down. The crew would have to tack back and forth across Laguna de Bay to reach the southern shore.

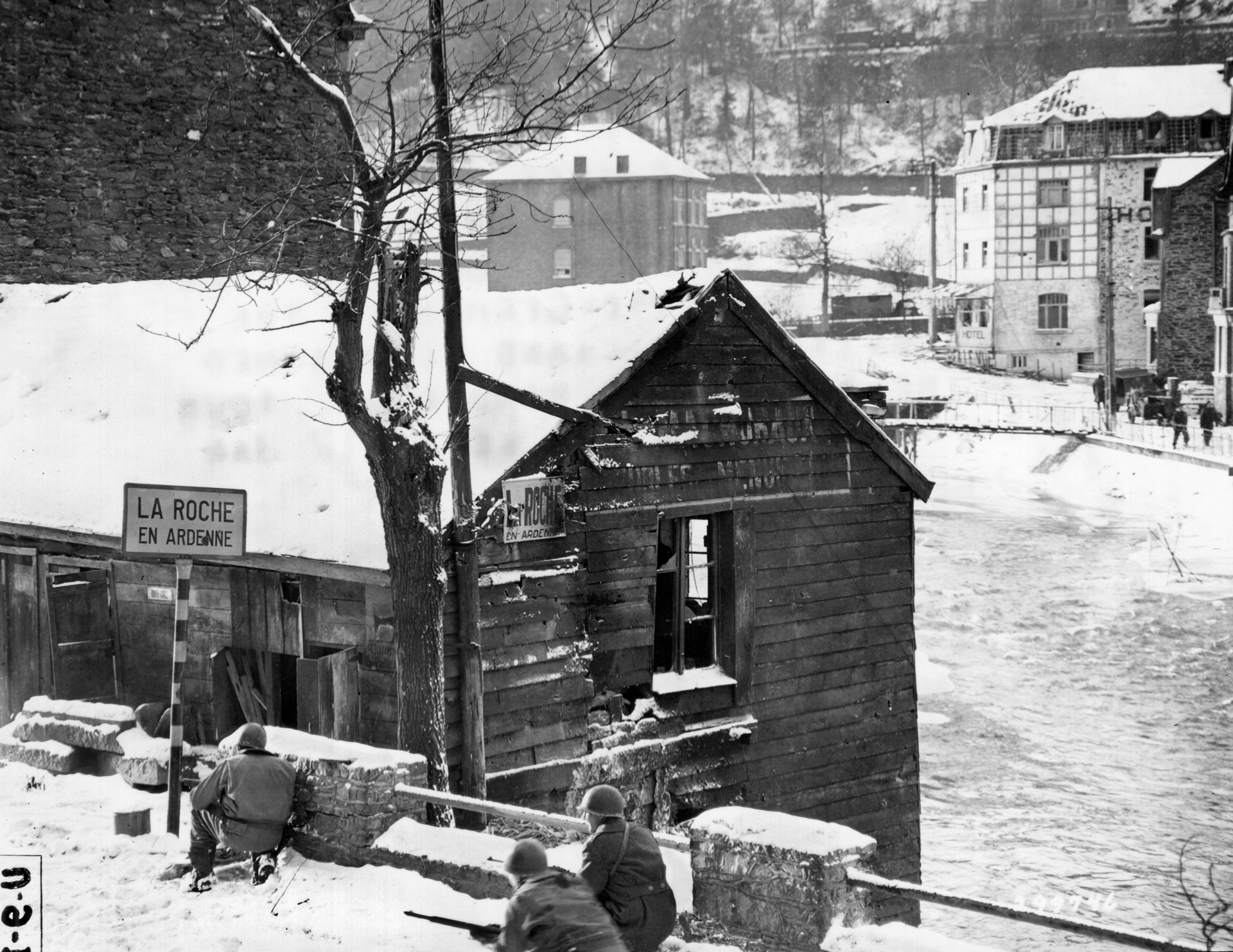

On the afternoon of February 22, everything went into motion. Colonel Soule’s diversionary column of glidermen, artillerymen, and tank destroyers formed up at Parañaque near the northwest corner of Laguna de Bay and began heading south along Highway 1. Paralleling the western shore of Laguna de Bay, the column finally stopped on the north bank of the San Juan River just before dark.

A second group that moved out that afternoon included Companies A and C of the 511th PIR, the engineer platoon from Company C, 127th Airborne Engineers, and the two guns and crews from Battery D, 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. Heading out from New Bilibid Prison, the group also turned south down Highway 1 and eventually turned off at Mamatid, along the western shore of Laguna de Bay and about five miles above the San Juan River. Here, the entire convoy went into bivouac under a canopy of trees. Major Burgess finally informed the men about the upcoming mission, specifying the role of each company, the engineers, and the two gun crews.

That afternoon the convoy of 54 amphibious tractors of the 672nd Amphibious Tractor Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Joseph W. Gibbs, moved out. The amtracs had been sitting at the Manila racetrack for a couple of weeks before making the trek southward through the streets. After traveling along Highway 1 to Muntinlupa, the convoy turned east and crawled into the waters of Laguna de Bay. Traveling southward until just after dusk, Colonel Gibbs led his amtracs ashore near Mamatid to join Major Burgess’s waiting paratroopers, engineers, and artillerymen. Once ashore, the crews and drivers were briefed on the operation and each member of the waiting attack force was assigned to one of the vehicles.

Finally, in the late afternoon, the reinforced Company B paratroopers moved out of New Bilibid Prison. Before the men left, the plan was revealed to them. “Finally, Lieutenant Ringler, our commanding officer, called us together and told us of the operation,” remembered Trooper Holzem. “There were over 2,000 American, Allied, [and] civilian prisoners in a Japanese internment camp about 25 miles beyond where our front lines were. Word had come in from Filipino guerrillas that the Japanese were going to execute all the prisoners on the morning of February 23rd.”

Lieutenant Ringler recalled the reactions of the men: “The men of B Company accepted the initial news of the jump in good spirits. I don’t believe that they initially understood the full danger of the mission until after our briefings were completed. At that time they became apprehensive of what could happen; however, with the amount of intelligence that we had we were very confident of success. We realized that we might be dropping into a hornet’s nest, which could result in considerable casualties. Regardless of our feelings, we knew that the mission was ours to accomplish. This was truly an ideal airborne mission, and this is what we were trained for.”

Taken from New Bilibid Prison to Nichols Field outside Manila, the troopers, engineers, and artillerymen who were to drop alongside the Los Baños Internment Camp were given their parachutes, ammunition, and rations. After assignment to one of the nine waiting Douglas C-47 transport planes, the men curled up under the wings of the planes and tried to get a few hours of sleep.

At this late hour, there was a last minute addition to the amtracs. Maj. Gen. Courtney Whitney, a staff officer with MacArthur who was charged with overseeing the entire guerrilla organization on Luzon, and a mysterious man dressed in civilian clothing, suddenly showed up and were given room in an amtrac. Although Whitney outranked Major Burgess, he came along solely as an observer.

Far away, along the southern shore of Laguna de Bay near the small barrio of Nanhaya, Lieutenant Skau and his recon platoon from the first two boats sweated it out for a whole day. Both boats had gotten ashore well before daylight on February 22, but the big banca carrying most of men of the platoon and all the heavy weapons and extra equipment was nowhere to be seen. When night fell and the boat had still not arrived, the lieutenant made alternate plans for the men at hand. Then, almost miraculously, the big banca loomed into view.

A little behind schedule, Skau and his recon platoon and about 80 Philippine guerrillas moved over to San Antonio, a small shoreline barrio located about one mile east of the village of Los Baños. Leaving a few recon men behind to mark the beach with white phosphorous grenades, the rest of the band headed inland. “Traveling overland through rice paddies, taking circuitous routes in order to skirt by the various enemy listening posts and outposts, it took us 10 hours to arrive at our objective [i.e. the internment camp],” wrote Terry Santos, a member of the recon platoon.

Around midnight, while most of the men were asleep, General Swing received information that the Japanese were moving large forces into the Los Baños area; this was confirmed by a night fighter pilot who saw numerous truck headlights on the highways. Had the secrecy been breached? Did the Japanese know that the raid was on? Too late to do anything at this hour, Swing decided to continue with the raid but notified the 2nd Battalion/511th PIR to be on standby for special movement south. He was hoping that the movement of the Japanese trucks through the Los Baños area was just a coincidence.

In reality, the movement of the Japanese was in response to the movement of the American amtracs from Manila to Muntinlupa. Lt. Gen. Masatoshi Fujishige, the Japanese commander in the area, had been informed of the movement of the amtracs but had been incorrectly told that they were American tanks. Assuming that the Americans were getting ready for a major drive down Highway 1, he shifted his forces accordingly, moving them west, away from the Los Baños prison area.

At 5:15 am on February 23, Major Burgess’s amphibious force was in motion. The LVT-4s crawled into the water and turned south. With the sun not yet up, the drivers would have to navigate the entire 7.4 miles to the San Antonio beachhead by compass, something that had never been done before. Moving at only five miles per hour in water (and 15 miles per hour on land), the trip would take just under 11/2 hours if everything worked out all right.

The next group to get into motion was the airborne segment. In addition to the paratroopers of Company B, 28 men from the Headquarters Company Light Machine Gun Platoon who had been attached for added firepower and nine engineers who had become separated from Colonel Soule’s relief column would also make the jump onto Los Baños. In all, Lieutenant Ringler would have about 140 men in his strike force.

“There was no moon,” Ringler wrote. “The sky was clear in the pre-dawn as we put on full combat equipment, then our parachutes, and loaded with our crew, several weapon bundles into the nine C-47s, under the command of Major Don Anderson, 65th Troop Carrier Squadron.”

As the B Company paratroopers climbed into their planes, they must have noticed the huge yellow letters painted on the side of one of the planes—RESCUE. Perhaps one of the C-47 crews wanted to let the internees know just exactly what was happening when the paratroopers hit the silk and the gunfire started, and they wanted everybody to get ready to leave.

The planes took off around 6:15 am and by 7 were nearing the Los Baños area. “As we dropped altitude and lined up with the drop zone,” wrote Captain Herbert J. Parker, the co-pilot on Anderson’s plane, “I flipped the cockpit switch to turn on the red light over the open rear door of the plane. At that signal, Lieutenant Ringler ordered his men to ‘stand up and hook up.’ They formed a row facing the rear of the plane, and each paratrooper checked the static line of the trooper in front of him, making sure that the chute was in order and the static line hook was attached to the metal anchor cable that ran overhead of the cabin.”

Down below on Laguna de Bay, the 54 amphibious tractors carrying the men from Companies A and C/511th PIR, the platoon from Company C, 127th Airborne Engineer Battalion, and the two 75mm pack howitzers and crews of Battery D, 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion were nearing their destination. Although guided only by their compasses, the drivers were approaching right on target. “We were told paratroopers would jump at dawn,” recalled Art Coleman, a machine gunner on one of the amtracs. “At first light we had eyes glued straight up as we neared the lake shore. Suddenly, at treetop height, nine C-47s rounded a hill….”

On the ground below, the recon platoon, slowed by the late arrival of the large banca, was just approaching the compound. “Just as we crested the bank of Boot Creek [on the south side of the prison pen],” wrote Terry Santos, “enemy fire erupted at 3 minutes before 0700. This alerted the Japanese gunners in the pillboxes.”

Charging the positions, two of the four recon men in Santos’s squad were wounded, and one of the 12 Philippine guerrillas with them was hit before two pillboxes were silenced. “Then suddenly a third, unreported machine gun opened fire on us,” Santos remembered. “We spotted this machine gun on a knoll near a large tree overlooking our exposed position. We kept it under fire until B Company troopers reinforced us.”

Up above, the pilots spotted the intended drop zone, a small field to the west of the compound. “As we crossed the edge of the drop zone,” co-pilot Parker stated, “[Major] Don [Anderson] ordered the jump. I threw the switch that activated the green light over the rear cargo door. Lieutenant Ringler kicked out his equipment bundle and jumped. His troopers were right behind him. It was 7:00 am, February 23, 1945.”

Ringler recalled, “I was jumpmaster of the lead aircraft, and at dawn, 0700 hours, we jumped and all landed on the DZ without casualties…. My time in the air consisted of only a couple of oscillations and I was on the ground. If there was any firing, it was very light or the enemy was off target.”

The crews of the amtracs watched in amazement as the paratroopers dropped out of the sky from an altitude of only 400 feet. At 6:58 am the amtrac drivers saw white phosphorous smoke identifying the landing beach, courtesy of Lieutenant Skau’s reconnaissance platoon.

The Japanese at Mayondon Point, an outcropping just west of San Antonio, fired upon the noisy, incoming horde of amtracs but scored no hits. As soon as the first wave of LVT-4s hit shore, one of Major Burgess’s paratrooper platoons scrambled out of the vehicles and set up a defensive perimeter around the beach. At the same time, the two 75mm pack howitzers were offloaded and went into action, firing at a Japanese position on a hill to the west. The empty amtracs and those in the succeeding waves then started down the road to Los Baños, 21/2 miles away.

Inside the Los Baños compound, all was suddenly noise and confusion. “That morning, as I walked out of the barracks with my family to line up for 7:00 am roll call, I looked up into the sky and over a field near our camp saw several C-47 transport planes,” remembered Robert A. Wheeler, a 12-year-old internee. “Suddenly, the sky filled with the ‘Angels’; the men of ‘B’ Company of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, floating down as if from heaven in their white parachutes. At that same moment, the Recon Platoon … hit the guard posts and began the race to the guard room where the off-duty guards had their rifles stored. Those guards were outside doing their regular 7:00 am morning exercise…. We all ran back into the barracks. With bullets flying just over my head through the grass mat walls, I lay on the floor under my bunk, eating my breakfast.”

Twelve prisoners of war, Army nurses that had been captured during the fall of the Philippines, were being held at Los Baños along with the civilian internees. Navy Lieutenant Dorothy Still Danner remembered working through the night taking care of a newborn baby. “It was just about 7 in the morning,” she wrote. “I had the baby in my arms when I noticed smoke signals going up. Nobody paid any attention to them. Then, all of a sudden we saw a formation of aircraft coming over. As the paratroopers started jumping out, the guerrillas and soldiers around the guard houses began killing the Japanese there.”

The paratroopers took approximately 15 minutes to assemble and move the 900 yards or so to the barrier around the compound. “After a rapid assembly,” remembered Lieutenant Ringler, “there was only minor enemy resistance, which was eliminated.” Some of the men used a dry riverbed on the edge of the drop zone that angled toward the camp to provide cover as they rushed forward.

Within 20 minutes of the first shots, the firing seemed to die down. Most of the Japanese guards were either killed or fled to the south and west, away from the incoming paratroopers. All the guards doing their morning calisthenics in an open area to the south of the compound were either killed or scared off. Although most of the sentries and pillboxes had already been silenced, some had to be eliminated by the Company B paratroopers. For the next few minutes, there was only sporadic shooting as the paratroopers, guerrillas, and recon men completed a building-by-building search.

While the fighting was going on at Los Baños, the 54 amtracs were rushing to the scene over a small dirt road. Lieutenant Danner was still helping the mother with the newborn baby and recalled, “Then the amtracs came in, crashing through the swali-covered fence near the front gate.”

Young internee Bill Rivers remembered, “A whole herd of the damnedest vehicles I’d ever seen, roared into the camp. When I saw the white star with the two bars on each side, I feared that the Russians had somehow rescued us, as I’d never seen that insignia before. But when I heard one soldier profanely order [another soldier nicknamed] ‘Red’ to give him the field phone, I believe I heaved a sigh of relief.”

As soon as the amtracs were inside the prison compound the Company A and C men dismounted and took up their positions, C Company moving to the south to set up a defensive perimeter against any sudden attacks by the Japanese, and A Company, with less than 50 men, deploying around the amtracs to help with the internees.

Two of the first men to jump out of the amtracs were General Whitney and his mysterious civilian companion. As Major Burgess recalled, the two men went into the camp and after a short time General Whitney came out carrying “several boxes well tied together containing documents which he deemed to be of considerable military significance. I didn’t believe it at first, but he was really sincere about keeping those boxes together and was with them all of the time.”

Although the contents of those boxes were never made public, it is believed that the information on the captured papers was used against the Japanese during subsequent war crimes trials.

Lieutenant Ringler was inside the camp, busy with other things when the amtracs showed up. “Upon our arrival inside the camp, the internees were very jubilant and excited as to the events taking place,” he wrote. “After a rapid survey of the situation, our company started to assemble the internees for a rapid movement out of the camp. With over 2,000 individuals, this became a turbulent mass of human beings. Trying to control them and keeping them in one place was almost an impossible task.”

Although most of the paratroopers were shocked by the emaciated condition of the internees, the civilians in turn thought that the soldiers looked enormous. Sister Louise Kroeger, a Catholic nun, recalled her first look at the American paratroopers. She wrote, “We thought each soldier an angel, and a giant one at that. They were massive compared to our malnourished men in camp.”

Recalled Lieutenant Danner, “Oh, we never saw anything so handsome in our lives. These fellows were in camouflage uniforms wearing a new kind of helmet, not those little tin pan [World War I-style] things we were used to seeing. And they looked so healthy and so lively.”

Of the 54 amtracs that had climbed onto the beach near San Antonio, a few had broken down during their trek to the prison compound since they were not designed for such long overland travel along a rutted, jungle track. While the crews tried to get them repaired, the rest of the amtracs had gone on to the prison compound and had gathered in an open field near the old university baseball diamond. Now all the paratroopers and amtrac crews had to do was get the internees into the waiting tractors.

“Many of the internees did not want to leave their huts or were returning to retrieve items left behind,” remembered Lieutenant Ringler. Eventually, the paratroopers came up with the idea of burning the internees out.

“The results were spectacular,” Major Burgess stated. “Internees poured out and into the loading area. Troops started clearing the barracks in advance of the fire and carried out to the loading area over 130 people who were too weak or too sick to walk.”

Nurse Danner, a trained military professional, agreed with the tactic. She wrote, “The American troops actually had to set fire to the barracks to get the internees moving.”

Although the internees were told to take only one or two small suitcases with them, they were showing up with boxes and suitcases in large numbers and all shapes and sizes. Not wanting to disturb the situation, Major Burgess and Colonel Gibbs had their men load the impediments into the amtracs along with as many people as they could accommodate. All the while, the faint rumble of artillery fire could be heard from far off in the distance, indicating that Colonel Soule’s task force was trying to break through to Los Baños.

On schedule at 7 am, Colonel Soule launched his task force southeast across the San Juan River toward two Japanese-occupied hills while a large guerrilla force launched an attack against Calamba, a Japanese-held barrio near the western shore of Laguna de Bay. By mid-morning, the glidermen and their attached artillery had formed a bridgehead across the river and had managed to wrestle the hills away from the Japanese. After setting up a blocking force to stop any movement by the Japanese 80th Division soldiers up Highway 1 from the south, most of the task force began moving southeast toward Los Baños, hoping to make their link-up with the reinforced 511th PIR and escort the paratroopers out of the area.

About 9:30 am, 21/2 hours after the Los Baños Raid had begun, Colonel Gibbs and his fully loaded amtracs finally began the slow crawl back to San Antonio and Laguna de Bay. Those people that could not fit in the amtracs began walking back to the beach.

Father William R. McCarthy, an internee Catholic priest, remembered those that walked. “Men, women and children followed,” he wrote, “bundles under their arms or dangling from sticks, carrying their scant possessions with them…. With many others we walked over the highway of freedom against a background of flames, as one straw barracks quickly followed another in an all-consuming fire fanned by the morning breeze.”

“After the first amtracs were loaded with the disabled, along with women and children, we were able to assemble all the remaining internees into a walking column and head for the Mayondon beach area,” wrote Lieutenant Ringler. “As our unit guarded the moving internee column we heard distant firing, indicating the enemy was probably sending elements to engage [Colonel Soule’s task force].” By approximately 11:30 am, the Los Baños Internment Camp was in flames and completely deserted.

The first amtrac reached the beach near San Antonio about 10 am. After all of the amtracs had assembled, including the four or five that had broken down and been repaired, Colonel Gibbs turned them northward and they crawled into the water for the trip back to Mamatid. There, a horde of Army ambulances and trucks waited to whisk the internees to New Bilibid Prison for help and medical aid.

“We entered the water,” wrote amtrac gunner Coleman, “having been instructed to stay away from the shore on the return. The 1st Platoon wanting more action, went close in with all those people on board and promptly the enemy opened up. They turned away and the bullets struck the tailgates which could withstand the fire better. No one was injured. On reaching the safe shore, the freed people boarded trucks and ambulances. We immediately returned to Los Baños.”

Although the Japanese at Mayondon Point fired at the retreating amtracs, their fire was mostly inaccurate. The only casualty was one of the LVT-4s. One pontoon on the side of the vehicle was punctured by the enemy gunfire and began to fill with water. After a short while, the amtrac settled low in the water. Fearing that the craft might sink, the crew simply radioed for help and another amtrac came alongside and took off all of the worried evacuees. Then, another amtrac towed the water-logged tractor all the way back to Mamitid.

After seeing the first group of about 1,500 internees and some of his paratroopers move away in the amtracs, Major Burgess and his remaining paratroopers, about 420, strengthened the perimeter set up around the San Antonio beachhead and waited. Off in the distance to the west, they could still hear the slight rumble of artillery fire coming from Colonel Soule’s task force. As intended, Major Burgess was still working under the belief that he was supposed to evacuate the remaining 720 or so internees in the amtracs once they returned and then march his men out on foot. However, seeing how many people the amtracs could carry out, he decided it would be safer to have his own troopers ride out with the second wave of internees.

Although Burgess could not establish radio contact with Soule, he was able to make contact with a Piper Cub artillery liaison plane flying overhead and carrying General Swing. After informing the general of the success so far, Burgess requested permission to evacuate his reinforced battalion along with the last group of internees by amtrac. When Swing suggested that Burgess might want to hang onto his beachhead deep within enemy territory until Soule’s task force reached him, the radio suddenly went dead.

Recalled Major Burgess, “I was so startled at the inquiry that, rather than reply, I turned off our radio…. I decided against the ‘suggestion’ and ordered the artillery radio to remain silent. To communicate further about the subject might have led him to order me to make contact with the 188th. Accordingly, we continued the evacuation of the beach by the amtracs.”

Colonel Gibbs and his noisy herd of amtracs returned to the San Antonio beach near 1 pm, and immediately the back ramps were dropped and the internees and their belongings were brought inside. The two 75mm pack howitzers of Battery D, 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, which had been firing into the high ground to the west of the beachhead all day, were picked up and placed atop the clutter of suitcases and packages in the center of a couple of amtracs. When all the remaining civilian passengers were safely on board, Major Burgess and his paratroopers climbed in. As the LVT-4s returned to the water, they drew fire from Japanese soldiers that were finally closing in on the American beachhead.

“As we entered the water,” remembered Coleman, “mortar and artillery fire descended on us but not a round found its target. The commander of the task force, Major Henry Burgess, later told me he could hear the Jap officers giving commands as we withdrew.”

As the amtracs scurried across the water, the crew of one of the 75mm pack howitzers pinpointed the location of a Japanese machine-gun position. Sergeant Harold Mason, one of the gunners, recalled: “The howitzer was high enough on the pile of baggage for us to contemplate firing a round back at the hill, which was the only place we thought the firing might be coming from. So we loaded and fired at the hill with a charge one, I believe. The machine gun stopped firing but the ‘[am]track’ was dipping from side to side and taking on water with each dip. The amtrac driver pointed a .45 pistol back at us and said, ‘Anyone loading that thing again gets a bullet in the head.’”

Needless to say, the American artillerymen stopped firing, but then, so did the Japanese.

By 3 pm, eight hours after the Los Baños Raid had begun, the beachhead at San Antonio was clear of internees and American soldiers. Burgess was one of the last men to leave the beach. The raid had been a complete success.

The first group of internees, which included all the sick and most of the women and children, had reached Mamatid about noon. Once there, the civilians were overwhelmed by American soldiers and Filipinos wanting to lend a hand wherever they could. A few hours later, the second group of internees was brought ashore and met the same reception.

West of Los Baños, Colonel Soule and his men spotted the first group of amtracs heading north across Laguna de Bay toward Mamatid crowded with internees and knew that, at least so far, everything was going as planned. A few hours later they watched as the amtracs returned to Los Baños, and a little after that, saw them heading north again, this time loaded with internees and paratroopers. Soule realized that the reinforced 511th PIR would not be fighting its way west to meet him, so he gave the order to begin a slow withdrawal to the San Juan River. Late in the afternoon, the entire task force was back where it had started.

The raid on the Los Baños Internment Camp understandably netted all sorts of publicity for General Swing and the 11th Airborne Division. News hounds interviewed the general, his men, and the internees themselves at New Bilibid Prison. Committees from among the internees wrote letters to General MacArthur, to Major Burgess, and to others. General MacArthur himself sent a letter to the 11th Airborne. “Nothing could be more satisfying to a soldier’s heart than this rescue,” he penned. “I am deeply grateful. God was certainly with us today.”

When viewed by military historians, the Los Baños Raid is generally accepted as a roaring success. “Of all of the 11th Airborne Division operations during the Luzon Campaign,” wrote the division historian, “the most spectacular was the hit-run raid on the Japanese internment camp at Los Baños.”

A 511th PIR historian wrote, “The whirlwind speed and split second timing of the attack was the main contributing factor in the success of the operation. The support of the 188th Glider Infantry and the 472nd F.A. Battalion, coming down from the north kept the Japs occupied in that sector so that the northern flank was secured.”

When studying the entire mission, the U.S. Army concluded, among other things, “Through the employment of airborne troops, tactical surprise can be obtained to a degree not possible in strictly ground operations.” It also went on to state that an “operation involving airborne, amphibious, and ground troops can be successfully accomplished with pinpoint precision when it is carefully and exactly planned and executed with rapidity.”

Preeminent airborne historian Major Gerard M. Devlin echoed the Army historians when he wrote in 1979, “Because of the highly accurate intelligence information, a perfect plan, and a faultless performance by the attacking troops, the Los Baños mission is still considered to be the finest example of a small-scale operation ever executed by American airborne troops. There is no doubt that it will remain a masterpiece of planning and execution and the blueprint for any future daring prisoner-rescue operation.”

Unfortunately, when the Japanese discovered that the Los Baños prisoners had been spirited away from under their very noses, they retaliated against the Filipino residents in the barrio of Los Baños. Shortly after finding the internment camp empty and destroyed by fire, the Japanese rounded up an estimated 1,400 Filipinos, tied them to the stilts holding up their houses, and set the structures on fire. For these crimes and for others committed against the Filipino people and the internees at Los Baños, Lt. Gen. Fujishige and Warrant Officer Sadaaki Konishi, a brutally sadistic supply officer at the camp, were summarily found guilty by the subsequent war crimes commission and executed.

Almost 50 years after the raid, General Colin Powell, while chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, sent a letter to the 11th Airborne Division association stating, “I doubt that any airborne unit in the world will ever be able to rival the Los Baños prison raid. It is the textbook airborne operation for all ages and armies.”

For the men of the reinforced 1st Battalion/511th PIR and Task Force Soule, the war continued. Although praise came from many quarters, the highest praise that the men could receive came from the internees themselves. “They were and are a special breed, those men who came that day,” wrote internee Robert Wheeler. “Superbly trained, thank God—men who went home after they served—going on with their lives—not complaining, humble, proud that they served. When I meet one of my ‘Angels’ for the first time, I take his hand and say, ‘Thank you for my life.’ To a man, they immediately insist, ‘I was just doing my job. You guys were the heroes.’”

Santos spoke for many of the rescuers when he wrote, “We, the liberators, have in the past, sometimes have been referred to as ‘Heroes.’ I disagree. The true heroes/heroines were the internees and the … POWs, [and] the U.S. Navy Nurses. These courageous people did not give up. They survived almost 1,200 days of incarceration, which emphasizes the invincibility of their spirit. Their faith in the United States and its armed forces remained unshaken. This, to me, is true heroism.”

Some of President Quezon’s Own Guerillas (PQOG) that took part in the raid: Dr. Leoncio Faraon, Manual T. Faraon, Dr. Pablo Faraon, Cornelio M. Manese, Pastor B. Timog, Eduardo J. Munsod, Pedro Castantino, Cicente Batacan, and Catalino Faustino.

Sari-sari owners that aided the PQOG: Francisca Naval and Olimpia M. Munsod.

There was also a prison camp on Palawan Island to the West of the Visayas. Unfortunately, all of the prisoners were murdered by the Japanese before they could be liberated. This pretty much validated MacArthur’s fears in ordering the rescue operations.