By William E. Welsh

The Prussian soldiers had been awake long before sunup on the morning of July 3, 1866, and were marching downhill to the Bystrice River in the rolling countryside of Bohemia, 65 miles east of Prague. A heavy rain fell from low-hanging clouds, turning farm fields and dirt roads into seas of ankle-grabbing mud. The soldiers’ mood reflected the morning gloom. Hunger and lack of sleep were their unwelcome companions.

Forming on high ground across the Bystrice was the 240,000-strong Austrian North Army, commanded by Field Marshal Ludwig von Benedek. The 62-year-old Hungarian-born commander, nicknamed “Lion of Solferino,” had been entrusted by Emperor Franz Joseph with vanquishing the Prussian invaders. The day before, Prussian scouts had located Benedek’s massive army encamped behind the Bystrice, where it blocked the main road to the Koniggratz fortress on the Elbe River. When the scouts reported their findings to the Prussian First Army commander, Prince Friedrich Karl, orders were issued for a general advance to begin at sunrise. On hand for the battle were Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke, mastermind of the modernized Prussian war machine, and King Wilhelm I. Not to be outdone, Minister President Otto von Bismarck also was in attendance, taking advantage of his position as a major in the Landswehr.

Von Moltke’s Army

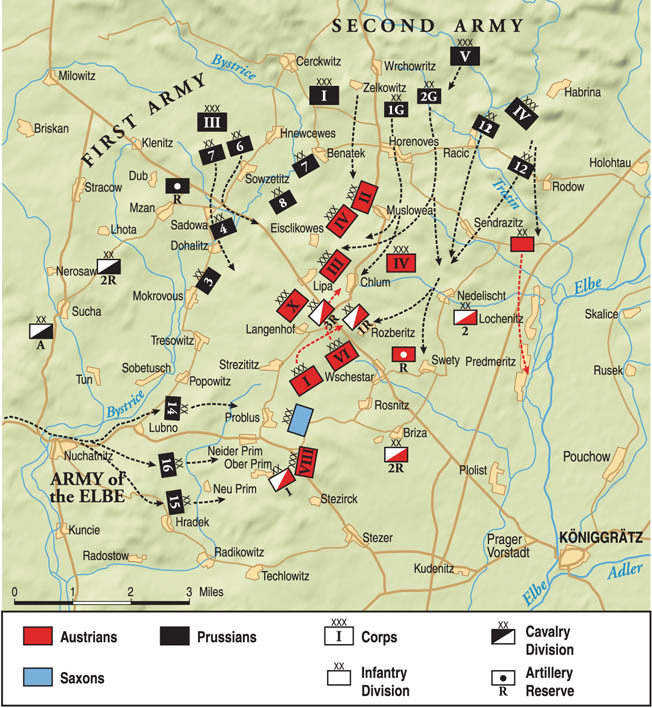

Moltke’s plan was relatively simple. The First Army’s 140,000 troops would pin the Austrians in place, while the 105,000-strong Second Army, encamped a half day’s march to the north, would sweep down on the Austrian right flank. The Prussians were clad in dark-blue uniforms, and most had left behind their spiked Picklehaube helmets for flat, nondescript field caps. They carried breech-loading Dreyse needle guns (named for their needle-shaped firing pins), wore bedrolls slung over their shoulders, and marched in hobnail boots.

In contrast, the Austrians “blazed all the splendor and variety of the old empire,” wrote London Times correspondent W.H. Russell. Austrian infantry were dressed in white coats and blue pants, sharpshooters wore forest-green greatcoats and sported broad-rimmed hats topped with feathers, hussars were clad in yellow-trimmed jackets, and black-booted cuirassiers wore crested helmets. The mood of the Austrian rank and file also contrasted sharply with that of the Prussians. Russell captured the spectacle that unfolded when Benedek rode forth from Koniggratz amid martial music from regimental bands to the cheers of his troops: “Despite the rawness of the day and the cold rain that fell on already sodden fields, Benedek’s progress toward the front brought color, music and a momentary gaiety to the army as if a festival were anticipated rather than a battle.”

It was a festival that had been in the works for quite some time. When Wilhelm I ascended the Prussian throne in 1861, he surrounded himself with ministers who shared with him a desire to elevate Prussia to the position of a great power, one that could successfully contest Austria for domination of the other German states. The king lacked the military acumen of his ancestor Frederick the Great. Aware of his shortcomings, Wilhelm relied heavily on Bismarck to orchestrate Prussian foreign policy and on Moltke to strengthen his kingdom’s military power to a point that would put it on par with the continent’s great powers: Austria, France, and Russia.

Austro-Prussian Competition Over the German Confederation

At the time of Wilhelm’s ascension, Germany remained subdivided into 35 small states and four free cities. One of the strongest of these was Prussia, which had gained the key territory of Silesia under Frederick the Great and other lands in central and western Germany in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat. The German Confederation, established at the Congress of Vienna, was meant by the great powers to replace the Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved in 1806.

The Prussians deeply resented the continuing domination of the German Confederation by Austria, and Wilhelm set about to unseat the Austrians as the first among equals of the German states. Misfortune befell the Austrian Empire when it was defeated by a French-Sardinian alliance in the Second War of Italian Independence in 1859. Moltke studied in great detail the lessons of that war and set about implementing a series of reforms intended to put Prussia ahead of its rivals in the areas of armaments, tactics, logistics, and military organization. During the period between Wilhelm’s coronation and the outbreak of hostilities with Austria, Prussia tripled the size of its army from 100,000 to 300,000 men. The logistics involved in supplying, transporting, and leading an army of this size into battle required a professional general staff.

Prussia and Austria, as defenders of German interests, went to war together in 1864 to expel the Danes, who were attempting to annex the duchy of Schleswig. This duchy and Holstein, to the south, were caught in the middle of the nationalist desires of both the Danish kingdom and the German Confederation. The Second Schleswig War provided the Prussians a chance to test their new weapons and tactics. After four months of fighting, the combined Prussian-Austrian Army drove the Danes out of the Elbe duchies. The subsequent treaty signed August 14, 1865, known as the Gastein Convention, called for Prussia to govern Schleswig and Austria to administer Holstein.

Bismarck felt that possession of both Elbe duchies would substantially augment Prussia’s holdings in central Germany, and he proceeded to meddle in Austria’s affairs regarding Holstein. By early 1865, relations between the two powers had deteriorated to the point that both sides were on the verge of mobilizing their armies. In a deft diplomatic move, Bismarck signed a mutual support treaty with the Italians in April 1865 to counteract the support Austria enjoyed with the German middle states. If war broke out, the Austrians would find themselves in the difficult position of fighting a two-front war.

As early as February 1866, the Austrians had shifted troops from far-flung eastern garrisons to Bohemia in preparation for war with Prussia. Aware that the Italians were moving troops to the Austrian border, Franz Joseph ordered a full mobilization of Austrian forces on April 27. Despite the urging of Bismarck and Moltke that he respond immediately by mobilizing Prussian troops, Wilhelm I was reluctant to order a countermobilization, for fear of appearing the aggressor in the eyes of Europe. As the days went by, his resolve waned under pressure from his ministers, and on May 12 he authorized the army to call up and equip its reserves. Moltke ordered the Prussian Army to make use of multiple railroad lines to move troops to the Saxon and Bohemian borders.

The Schleswig-Holstein crisis came to a boil the following month. Exasperated by Prussian interference in its administration of Holstein, the Austrians put the matter before the German Diet on June 1. By putting the matter before the German princes, the Austrians violated the Gastein Convention, which instructed that all matters regarding Schleswig-Holstein were to be settled between Prussia and Austria without the involvement of the other German states. A week later, the Prussians invaded Holstein with a sizable force. The small Austrian garrison at Kiel withdrew by rail to Bohemia without firing a shot. In a meeting of the German Diet at Frankfurt on June 14, the German middle states threw their support behind Austria.

Prussia’s Advantages in Mobile Warfare

Although Prussia’s population of 18 million was about half of the population of the Austrian Empire, Prussia’s mandatory service requirement ensured that the two powers had roughly the same number of men under arms. The coming conflict would give Prussia its first chance to employ new transportation and communication technologies in a large-scale campaign. Moltke intended to use the railroad to speed Prussian mobilization and employ the telegraph to connect war planners in Berlin with Prussian armies in the field. Once the armies had crossed the border, they would converge on the Austrian main army from different directions and surround it in what Moltke called a Kesselschlact, or pocket battle. He arranged for the military to use five different railway lines to move troops to the Austrian border at the outbreak of hostilities. For their part, the Austrians had only one line running north from Vienna.

New advances in rifled artillery and the development of the breech-loading rifle, with which the Prussian infantry would be armed, also would play an important role in the conflict. Prussian infantry entered the conflict armed with the Dreyse needle gun. Loaded at the breech rather than the barrel, the rifle could be loaded more rapidly and fired from a standing, kneeling, or prone position, unlike muskets, which were best loaded while standing. The ability to load and fire kneeling or lying down meant that soldiers could conceal themselves in the terrain and present a smaller target to the enemy. The Prussians had experimented in the Schleswig War of 1864 with new rifle tactics in which infantry battalions broke into smaller companies and platoon formations that allowed them to make maximum use of the tremendous firepower of the needle gun. In contrast, the Austrians clung to more traditional shock tactics in which tightly packed masses of men stormed enemy positions with fixed bayonets, seeking to overwhelm them with the sheer shock of their charge.

The Plans of Moltke vs Benedek

Bismarck saw the Austrian violation of the Gastein Convention as an excuse to expel Austria from German politics once and for all. He immediately dispatched a letter disbanding the German Diet. While this formality was ignored by Austria and its allies, it reflected Prussia’s desire to establish a new German political body in which it would be the prime authority. To carry out the political aims, Moltke set in motion a well-crafted plan. Three Prussian armies would converge on Saxony and Bohemia, trapping Austria’s North Army in a pocket where it would be forced to surrender or face destruction.

Prussia’s Army of the Elbe, led by General Karl Erhard Herwarth von Bittenfeld, numbering 46,000 men in three infantry divisions, was instructed to invade Saxony and occupy Dresden. Once Herwarth’s army had neutralized Saxony, Moltke’s plan called for the Army of the Elbe to join the 94,000-strong Prussian First Army under Prince Friedrich Karl. Together, the two armies would invade Bohemia from Lusatia. Friedrich Karl, a veteran commander who had led the Prussians in the Second Schleswig War, commanded three infantry corps and two cavalry divisions. Meanwhile, the 115,000-strong Prussian Second Army, led by untested Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, would march into Bohemia from Silesia. Moltke’s plan called for First Army to capture the Iser River crossings in Bohemia and advance toward the Elbe, where it would make contact with the Second Army. Once contact was made, the two armies would plot the final moves designed to squeeze the Austrians as in a vice.

The Austrians had no comparable plan in effect at the beginning of hostilities, and Field Marshal Benedek was less than brimming with confidence. Benedek had fought with distinction seven years earlier during the humiliating Austrian defeat at Solferino. During that decisive battle, he had disobeyed orders to withdraw the forces under his command in order to enable the remainder of the army to escape to safety across the Mincio River. His performance was hailed throughout the Austrian empire and earned him his dubious leonine sobriquet. But while Benedek exhibited bravery during battle, he lacked both strategic ability and arrogant confidence. Nevertheless, Franz Joseph promoted him to supreme commander of Austrian forces and charged him with defending the crown.

Austria’s Defensive Advantage

The conflict began with the Austrians benefiting from a strong defensive position behind a curtain of high mountains that separated Bohemia from Saxony and Prussia. Should the Austrians need to fall back to a second line of defense, the three 18th-century Elbe fortresses at Josephstadt, Konnigratz, and Theresienstadt, known collectively as the Northern Quadrilateral, offered the most logical place for a strong defensive line from which the Austrians could contest Prussian attempts to cross the river. Benedek began concentrating Austrian forces in Olmutz, east of Bohemia in Moravia, in late May.

Herwarth’s Army of the Elbe crossed into Saxony on June 16, forcing Crown Prince Albert’s smaller 32,000-strong Saxon army to retreat into Bohemia. As he made final preparations to lead his massive North Army west into Bohemia, Benedek sent a 28,000-man vanguard consisting of the Austrian I Corps and 1st Light Cavalry Division, under the command of General Eduard Clam-Gallas, ahead of the main army to join forces with the Saxons. Clam-Gallas’s orders were to take up a strong defensive position behind the Iser River and delay the Prussian advance as long as possible.

On the same day, Franz Joseph ordered Benedek to shift his base of operations from Moravia to Bohemia. Benedek drew up plans for a westward march that he estimated would take his large army two weeks to accomplish. The elaborate plans for the North Army’s march into Bohemia called for its six infantry corps, four cavalry divisions, and their supply trains to fan out over five roads.

Prussia’s Official Declaration of War

After the fall of Saxony, Moltke ordered the Prussian First and Second Armies to march from their staging areas to the Bohemian border on June 19. Two days later, the two armies arrived on the Prussian border and awaited final orders to cross into Bohemia. On that same day, Benedek received at his field headquarters an official declaration of war signed by King Wilhelm I. Moltke’s plan called for the two armies to advance into Bohemia from two different directions and establish contact with each other at the village of Jicin, a key crossroads on a plateau between the Iser and Elbe Rivers.

The Prussian First Army crossed unopposed into Bohemia on June 23 after Clam-Gallas chose not to block the mountain passes. The First Army occupied Reichenberg the following day. Despite Moltke’s clear orders to march as quickly as possible toward the town of Jicin to await the arrival of the Prussian Second Army, Prince Friedrich Karl camped for two days at Reichenberg to replenish his supplies.

Meanwhile, the Prussian Second Army, climbing through the mountains into Bohemia on June 26, found its way blocked by large detachments from Benedek’s North Army marching west from Olmutz. Moltke sent orders by telegraph on June 23 to Friedrich Karl urging him to press on to Jicin in order to draw off Austrian forces that might block the passage of the Prussian Second Army through the high mountains to the east.

Spurred into action by Moltke’s orders, First Army’s 7th and 8th Divisions reached the Iser crossings the evening of June 26. Clam-Gallas, by then united with the Saxons for a combined force of 60,000 men, received orders from Benedek imploring him to hold the Iser line at any price. The two sides clashed at Podol on June 26, and again on June 28 at Munchengratz. At Munchengratz, the Austrians slipped east through a foiled Prussian trap, but the following day were driven from Jicin by the Prussian 5th Division under General Ludwig Tumpling. When Friedrich Karl advanced beyond Reichenberg on June 26, Moltke lost contact with the Prussian First Army for 72 hours. Because of mounting frustration over communications between Berlin and the two Prussian armies in the field, Moltke, Bismarck, and King Wilhelm left Berlin on June 29 to join the First Army at Jicin.

When he learned that a large Prussian force was advancing on the right flank of his route of march toward Jicin, Benedek dispatched the VI Corps and X Corps to slow the Prussians’ progress. While the two corps delayed the Prussian army to his north, Benedek would continue west with the bulk of North Army to Jicin. The Austrian VI and X Corps attacked the Prussian Second Army’s left and right flanks, respectively. Prussian V Corps commander General Karl Steinmetz soundly defeated Wilhelm Ramming’s VI Corps on June 27 at the village of Vysokov, forcing Ramming to fall back to the village of Skalice, where his corps was relieved by Archduke Leopold’s VIII Corps.

“A Catastrophe is Inevitable”

The clash between Austrian General Ludwig Gablenz’s X Corps and Alfred Bonin’s Prussian I Corps at Trautenau Pass that same day brought strikingly different results. Despite heavy losses, Gablenz managed to drive the Prussians back into the mountains. Gablenz subsequently withdrew when the Prussian Guard, which had emerged unopposed from Eipel Pass, outflanked his position.

The last significant action in the sector occurred on July 28, when Steinmetz drove off the Austrian VIII Corps at Skalice. Following that action, Benedek issued new orders for the North Army to move upstream of Josephstadt and concentrate at Koniginhof on the Elbe, a short distance from Skalice. He held no council of war and gave no reason for his change of orders, leaving his corps commanders wondering which Prussian army he intended to fight first.

June 30 dawned with the Austrian North Army concentrated in the Dubenec Plateau between the upper reaches of the Bystrice and Elbe Rivers. Over a four-day period, the Austrians had lost more than 30,000 men as the two armies maneuvered for a set-piece battle. The losses weighed heavily on Benedek, who believed that his army stood little chance of defeating the Prussians in a large-scale encounter. Accordingly, Benedek decided to pull back behind the Elbe in the vicinity of the Koniggratz fortress. “Debacle of Iser Army forces me to retreat in the direction of Koniggratz,” Benedek telegraphed the emperor, laying the blame unfairly on Clam-Gallas, whom he replaced at the head of the Austrian I Corps with his second in command, General Leopold Gondrecourt. That evening, the Austrian North Army began marching south toward the Jicin-Koniggratz road, which passed through the small village of Sadowa on the Bystrice River.

Rather than push his corps commanders to get their troops to the east bank of the Elbe as quickly as possible, Benedek allowed his army to encamp on July 1 on a string of hills overlooking the Bystrice, a shallow tributary of the Elbe. While the stream itself posed no obstacle to foot soldiers, artillery had to be driven through fords or bridges. Benedek then sent a second telegraph to Franz Joseph from Koniggratz, urging him to sign an armistice with the Prussians. “Pray conclude peace at any price,” wrote Benedek, “a catastrophe is inevitable.”

A Wide Austrian Deployment

On June 30, Bismarck, Moltke, and King Wilhelm arrived at I Corps headquarters east of Jicin. Moltke immediately ordered scouts to comb the countryside along both banks of the Elbe to locate the North Army’s exact position. Moltke assumed that Benedek would withdraw east and set up a defensive line behind the Elbe with his right flank anchored on Josephstadt and his left flank anchored on Koniggratz.

Rather than order the Prussian Second Army to shift west to link up with the Prussian First Army, Moltke ordered it to remain in place. At Koniginhof, the Second Army controlled the upper Elbe crossings and was in a position to march south on either bank, depending on the strategic situation. By keeping a day’s march between the two Prussian armies, Moltke was confident that he would be able to outflank Benedek, regardless of where the Austrian chose to make a stand.

Unsure whether the main Prussian attack would come from the west or north, North Army operations chief, General Gideon Krismanic, had drafted orders for the Austrian infantry to deploy on a wide arc that stretched for four miles from the Bystrice to the Elbe. The Austrian center was situated directly opposite the village of Sadowa on the west bank of the Bystrice, straddling the Koniggratz road. Located on the east bank of the Bystrice were about a half dozen hamlets. Adjacent to the road on the south side was the Hola Forest and on the north side the much larger Svib Forest. Austrian engineers set to work clearing trees in front of the Austrian center to provide clear fields of fire and constructing abatis from the logs. They also sited their guns and marked the ranges to ensure effective artillery fire.

On the left flank, atop the hills of Prim and Problus near the village of Nechanice, Krismanic placed the Saxons, the Austrian VIII Corps, and the 1st Austrian Light Cavalry Division. In the center, on the hills of Lipa and Chlum, he positioned the Austrian III and X Corps. On the right flank, anchored on Nedelist, were the Austrian II and IV Corps and the 2nd Light Cavalry Division. The Austrian reserve, placed in the center of what became known as the Bystrice pocket, consisted of I and VI Corps, three heavy cavalry divisions, and 16 batteries.

The plan had several key disadvantages. The flanks were not well anchored, and the entire position was in the form of a salient that made it difficult for the wings to support each other and would make withdrawal difficult if the battle went against the Austrians. Krismanic received orders recalling him to Vienna to explain North Army’s questionable state of affairs to the emperor, and he relinquished his authority on the eve of the battle to his replacement, General Alois Baumgarten.

“How Long is This Towel Whose Corner We’ve Grabbed Here?”

Following the capture of Jicin, the Prussian First and Elbe Armies had camped at Horice, a short distance east of Jicin. Moltke instructed Karl Friedrich to wait there until Prussian scouts were able to report the exact location of the Austrian North Army. When the scouts located the enemy’s position on the evening of July 2, Karl Friedrich immediately issued orders for his troops to begin a general advance to the Bystrice at 2:30 am. His orders included no instructions for the Second Army, as he hoped to defeat the Austrians on his own and hoard the glory. When a staff officer showed Moltke a copy of the orders, the chief of staff promptly issued revised orders that included instructions for the Second Army to make a forced march south and deliver a sledgehammer blow to the Austrian right flank.

By 4 am, Friedrich Karl’s six divisions were ready for battle. Four divisions formed the main battle line above and below the village of Sadowa, ready to advance across the Bystrice, with two more in reserve. An hour later, Crown Prince Wilhelm received orders from Moltke to march swiftly south. Meanwhile, Herwarth’s three divisions marched south to Nechanice, where they would attempt to turn the Austrian left flank.

The first shots of the battle were fired at 6:30 am by fusiliers from General Philipp von Canstein’s 15th Division of the Army of the Elbe. The Prussian riflemen drove off Saxon pickets attempting to dismantle the plank bridge over the Bystrice at Nechanice. Hearing the firing, Austrian and Saxon troops nearby formed for battle.

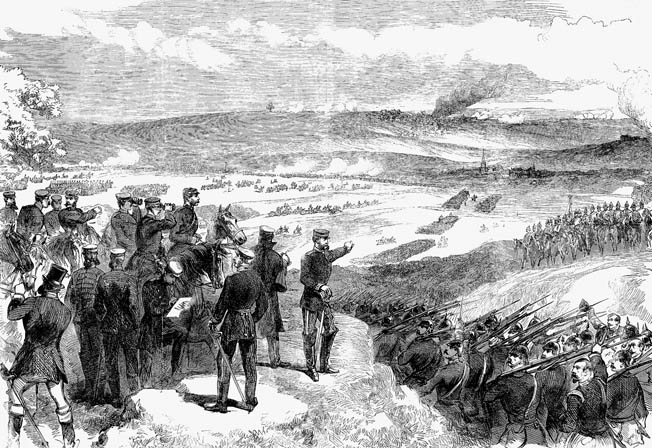

King Wilhelm I, accompanied by Bismarck, arrived on horseback at 7:45 am at the Prussian command post established by Prince Friedrich Karl atop Dub Hill overlooking the Bystrice. There they joined the prince and Moltke, who were doing their best to survey the enemy position through a thick blanket of mist that clung to the valley. An artillery duel between the two sides had begun just 15 minutes before. As if on cue, an Austrian shell exploded 20 yards from the king, causing brief alarm but failing to harm the Prussian monarch.

Spurring his horse, the king rode to Moltke’s side. “How long is this towel whose corner we’ve grabbed here?” the king demanded, wanting to know whether they faced the entire Austrian army or simply a determined rear guard. “We don’t know exactly; it’s at least three corps, perhaps the whole Austrian Army,” replied Moltke calmly.

Prussians in the Svib Forest

At 9 am, Friedrich Karl ordered a general advance across the Bystrice. The Prussian Pomeranian II Corps, comprising the 3rd and 4th Divisions, forded the stream with relative ease and drove the Austrian jaegers from the X Corps back to Langenhof Hill. Austrian shells crashed among the advancing Prussians with devastating results. Efforts to unlimber Prussian guns were unsuccessful as the Austrians zeroed in on the gun crews, smashing them before they could bring their guns into action. The shelling was so intense that the troops from the 4th Division sought shelter in the Hola Forest.

“The bombshells crashed though the walls as if through cardboard. Finally, raging fire set the village ablaze,” wrote one Prussian soldier. “We withdrew to the left, into the woods, but it was no better there. Jagged hunks of wood and big tree splinters flew around our heads.”

To the north, the lead battalions of hard-fighting Eduard Fransecky’s 7th Division crossed the Bystrice and cleared the village of Benatek of enemy pickets. Following closely behind 7th Division was General Heinrich Horn’s 8th Division. To the north of the sprawling Svib Forest was Benatek, and to its immediate south was the village of Cistoves. Before the Prussians could put troops on unoccupied Masloved Hill, they would need control of the Svib Forest to protect their lines of communication. At 8:30 am, Fransecky personally led his battalions into the wooded tract.

The Fight For the Svib Forest

Fearing that his troops might be left out of the fighting, Austrian IV Corps commander, General Tassilo Festitics, rode west to Masloved at 7:30 am to reconnoiter enemy troop positions. He believed that if his troops occupied Masloved, they would be in a position to counterattack Prussian infantry and possibly drive them back across the Bystrice. Festitics dispatched messengers to both his second in command, General Anton von Mollinary, and II Corps commander General Karl Thun, directing them to march west and occupy Masloved and Horenoves. While Festitics rightly assumed that enemy possession of the two hills would endanger the right flank, he failed to consider that the Prussian Second Army, whose location was still unknown to the Austrians, might be able to slip around the right flank.

Benedek broke off a meeting with Krismanic and Baumgarten at the Koniggratz fortress when informed that the Prussians were attacking in force. Passing through cheering ranks of soldiers, Benedek rode west on the high road toward the sounds of battle. Arriving at Lipa around 9 am, he assessed the situation with Archduke Ernst, commander of the Austrian III Corps. Benedek learned that the archduke had sent two brigades forward to engage the Prussians in violation of Krismanic’s orders, which called for the units to hold the high ground and await Prussian attacks. Benedek immediately called them back. It was not the last time that the field marshal would have to countermand subordinates’ faulty orders.

For close to three hours the fighting raged in the dark confines of Svib Forest. Shells from 50 guns atop Lipa Hill roared into the forest. When the Prussians emerged from the woods, General Karl Appiano’s brigade from III Corps at Cistoves counterattacked, forcing the Prussians to fall back to the protection of the forest. This assault was followed by a flank attack from the east by General Emerich Fleischacker’s brigade of the IV Corps.

The Austrian columns made easy targets for the Prussians, who had divided into smaller, platoon-sized formations more suitable to the forested terrain. “We attempted a bayonet attack first on the northeastern edge of the wood, and then several times inside,” an Austrian officer wrote. “Each time the enemy refused to stand his ground. Instead he kept up a steady fire until we had closed to within 80 paces, then dropped back using the terrain for cover.”

While the battle raged in Svib Forest, shrapnel from a Prussian shell sheared off Festitics’s foot, and Mollinary immediately assumed command of IV Corps. By 10 am, Mollinary was feeding fresh troops into the fight in an effort to cut off Fransecky. General Carl Pockh’s brigade from IV Corps charged into the south end of the woods, while two more brigades from Thun’s II Corps attacked the north end of the woods. At 10:30, Fransecky ordered a general withdrawal toward Benatek. Exiting the woods to the south, Fransecky’s men were pursued by Pockh’s columns, but fresh Prussian battalions provided covering fire for their fellow soldiers. Altogether, Fransecky’s men had withstood 13 charges by the Austrians with a loss of more than 2,000 men.

Prussians on Hradek Hill

In a desire to try to retake Svib Forest, Fransecky sent a messenger to Dub Hill requesting reinforcements. Friedrich Karl prepared to commit his two remaining divisions, but Moltke was adamant that they be kept in reserve. The king listened to arguments on each side. “I must seriously advise your majesty not to send General Fransecky a single man of infantry support,” Moltke warned, adding that Fransecky’s situation could only be improved by the arrival of Second Army’s vanguard. Wilhelm overruled his nephew.

After Mollinary’s request for heavy cavalry from the reserve to help drive the Prussians back across the Bystrice was denied by Benedek, he rode to Lipa at noon to consult in person with the field marshal. Mollinary proposed an assault by three Austrian corps across the Bystrice that would drive a wedge between the Prussian First and Second Armies. Minutes before Mollinary’s arrival, Benedek had received a message informing him that the Prussian Second Army was marching south to the battle. Fearing that storming the Prussian positions would result in mass casualties, Benedek refused to take the offensive. He ordered Mollinary and Thun to break off their attack and fall back to their original positions. To further bolster the Austrian right, Benedek ordered Ramming’s VI Corps in the reserve to shift north to bolster the right flank.

To the south, Herwarth had two of his three divisions across the Bystrice by midday. Prussians armed with the deadly needle gun shattered Saxon battalions that put up token resistance before falling back to the relative safety of Prim Hill. The Saxon retreat left Hradek Hill, to the south of Prim and Problus, open for the Prussians to occupy. Canstein’s men swarmed over the key position, and the Prussians dragged guns up Hradek to enfilade enemy positions. General Joseph Weber, who had replaced Archduke Leopold as VIII Corps commander, sent two of his brigades to stabilize the Saxons and attempt to take Hradek back from the Prussians. The Prussians shattered the Austrian counterattack through a combination of artillery and rifle fire.

“We are Fighting for the Very Existence of Prussia”

By noon the mist had cleared from the valley floor, and the Prussian leaders atop Dub Hill had their first unobstructed view of the battlefield. The Prussian center was a scene of complete carnage, the landscape strewn with dead and mangled bodies that had absorbed the full fury of well-served Austrian batteries. In the distance, Ramming’s VI Corps was seen moving toward the front. Fearing the worst, King Wilhelm inquired whether Moltke had contingency plans for a retreat. “Here there will be no retreat,” Moltke said coolly. “We are fighting for the very existence of Prussia.” Observing the timely arrival of the Second Army’s vanguard, Moltke reassured the nervous monarch, “Success is complete; Vienna lies at your feet.”

Riding with the vanguard, Crown Prince Wilhelm and his staff reconnoitered enemy positions atop Masloved and Horenoves from a safe distance while Prussian guns unlimbered and began shelling the Austrian forces on the heights to the south. When sufficient numbers arrived to warrant an advance, a single Prussian fusilier battalion captured Horenoves from a small party from the Austrian II Corps, which surrendered without a fight. A short time later, the lead battalions of General Louis Mutius’s VI Corps crossed the Trotinka River east of Horenoves and brushed aside enemy pickets, occupying the villages of Racic and Trotina.

By 1 pm, Austrian troops of the II and IV Corps abandoned their forward positions and began retreating to their original positions. Prussian troops from the 1st Guard Brigade, supported by a portion of Fransecky’s 7th Division which had reoccupied the Svib Forest, advanced south at 2 pm through Cistoves. Dividing into smaller companies and platoons, the 1st Guard Brigade hurried south along a sunken road that offered a strong measure of cover toward the village and heights of Chlum. By then, Herwarth had all three of his divisions in action to the south. Shortly after seizing the twin hills, Herwarth’s guns began shelling Gablenz’s X Corps atop Langenhof Hill. Moltke’s envelopment strategy was going precisely according to plan.

Chaos in the Austrian Ranks

When the 1st Guards units arrived at Chlum, the village was in flames from Prussian artillery fire. Shaken by the continuous shelling of Prussian guns, several hundred Hungarians of Appiano’s Brigade promptly surrendered. Other battalions of Appiano’s brigade were mowed down by Prussian rifles as they attempted to retake the village. “The Prussians materialized in Chlum as if from thin air,” Baumgarten wrote.

Benedek realized by mid-afternoon that his army was in imminent danger of being surrounded and cut off. Even so, he had not realized the depth to which the Prussian Second Army had breached his right flank. From his position on the southwest slope of Lipa, he had just issued orders for Ludwig Piret’s I Corps brigade to march south and retake Problus when his adjutant, August Neuber, informed him at 2:45 pm that the Prussians had taken Chlum and were in the Austrian rear. Hoping to retake Chlum, Benedek issued orders through his staff for Ramming and Gondrecourt to take their reserve corps and assault Chlum. Benedek and his staff then rode south to assess firsthand the severity of the situation. After trying unsuccessfully to rally Austrian troops retreating from Chlum, Benedek and his staff turned south toward Langenhof.

Benedek never made it that far. Rather than setting up a new headquarters from which he might establish a rearguard to cover the retreat, the Austrian field marshal rode wildly about the field, vainly attempting to rally individual units. When the Prussians atop Problus and Chlum began shelling the position of the Austrian reserve units, a substantial number of soldiers dropped their muskets and packs and fled across the countryside to escape the surging enemy.

The sea of panicked Austrian troops fleeing from the front lines swept Benedek and his small entourage along with it toward the Elbe. Troops from seven corps and five cavalry divisions were squeezed into a pocket no more than a half mile wide, trying to reach the Elbe. Although Benedek had ordered four pontoon bridges constructed earlier in the day in case retreat became necessary, neither the troops nor their officers had been told how to reach them.

In the chaos unfolding in the Bystrice pocket, it was impossible for the two Austrian infantry corps commanders charged with counterattacking Chlum to coordinate their actions. Nevertheless, Ramming and Gondrecourt ordered their troops to change direction and attack. Ramming’s counterattack began around 3:15 pm, with General Ferdinand Rosenzweig’s brigade on the left sweeping aside a few companies of Prussian fusiliers stationed around the village of Rozberic. Among the Prussian officers who received a taste of combat at Rozberic was Lieutenant Paul von Hindenburg, who would obtain worldwide fame in the next century.

Benedek’s Catastrophe

The Prussians retreated north on a sunken road from Rozberic toward Chlum, with Rosenzweig’s infantry in hot pursuit. Without realizing it, the pursuing Austrians ran into a trap. Prussian infantry hiding in the fields to the west sprang up and fired at point-blank range into the stunned Austrians. In an effort to support Rosenzweig, Ramming ordered General Georg Waldstatten’s brigade into action, but retreating Austrian cavalry rode through their own lines, severely disrupting the formations. Before they could realign, Prussian rifles and cannons ripped into their ranks. Realizing the futility of his situation, Ramming called off the attack. In a short time he had lost nearly 6,000 men.

Gondrecourt’s attack followed on the heels of Ramming’s attack. As he repositioned his three brigades to face north, the Prussians poured continuous rifle fire into the Austrian I Corps. Gondrecourt personally led a Slovenian regiment up the slopes of Chlum into a hail of enemy fire. After taking heavy losses, he broke off the attack, having miraculously survived the experience. Gondrecourt’s attack sputtered out before 5 pm, and the survivors fled east.

Two Austrian heavy cavalry divisions from the reserve formed up facing west just before 4 pm to relieve pressure on the Austrian center. Prince Wilhelm of Schleswig-Holstein’s 1st Cavalry Division and General Carl Coudenhove’s 3rd Division lined up on the north and south sides of the Koniggratz road. Prince Wilhelm intended to attack Langenhof, while Coudenhove aimed for Problus. Holstein’s troopers never reached their objective. Heavy fire from Prussian fusiliers on the valley floor forced the prince’s division to retire, while a wall of shrapnel and rifle fire shattered Coudenhove’s attack before his troops could reach their objective. In a half hour’s time, the Austrians lost more than 700 troopers in the suicidal charge.

Demoralized Austrian infantry milled around the west bank of the Elbe before the palisade guarding the causeway leading to Koniggratz. Shortly before 5 pm, a large body of Austrian and Saxon soldiers smashed through the gates and swarmed over the causeway. The garrison inside mistook the Saxons for Prussians and fired on the mob. Ramming arrived and attempted to restore order. Meanwhile, Benedek and his small escort gave up trying to rally individual units. With tears of sorrow and rage streaming down his face, the defeated field marshal rode away from the field.

When he reached the fortress, Benedek ordered the pontoon bridges destroyed for fear the Prussians would capture them intact. His decision left large numbers of Austrian and Saxon infantry and cavalry stranded on the west bank. Many refugees unwilling to wait for the bottleneck at the causeway to subside plunged into the river and drowned. That night Benedek telegraphed Franz Joseph: “The catastrophe I warned you of two days ago happened today.” Refusing to accept responsibility for the disaster, Benedek blamed foul weather and disloyal subordinates for the debacle.

The Prussian cavalry, which had ridden into battle behind the infantry, was not in a position to pursue the retreating Austrians. A large portion of the Prussian Second Army was still en route to the battlefield and would not arrive until after nightfall. For these reasons, Moltke decided against a night pursuit.

The Peace of Prague

Austrian casualties from Koniggratz totaled 24,000 killed and wounded and 20,000 captured, while the Prussians lost 9,000 killed and wounded. Moltke’s decision not to push Prussian units across the Elbe the next day gave Benedek and his generals time to reorganize and begin the long retreat to Olmutz. When the Prussians finally crossed the Elbe on July 5, Moltke sent the Second Army east to pin the North Army at Olmutz while First Army occupied Prague and marched on Vienna.

The Austrian situation in the Seven Weeks’ War continued to deteriorate. The Italians launched a fresh offensive against the Austrians in the south, and the Prussian First Army pillaged Austrian crown lands in Bohemia and Upper Austria. The remaining German states surrendered to Prussia, and France showed no interest in assisting the Austrians. With no help in the offing, Franz Joseph surrendered to King Wilhelm on July 22.

The Peace of Prague signed on August 23 called for Austria to cede Holstein and withdraw from German politics altogether. In addition, Franz Joseph had to pay 30 million silver florins in compensation for Prussia’s wartime expenses. As a result of its triumph over the German middle states, Prussia greatly expanded its territory through the annexation of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, Nassau, and Frankfurt. The creation of the German empire substantially altered the balance of power on the European continent and set the stage for two catastrophic world wars in the coming century.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments