By John Brown

Tobruk, the vital Libyan seaport on the coast of Cyrenaica, fell to General Erwin Rommel and his victorious Afrika Korps in less than 24 hours after an unexpected and devastating air, armor, and infantry attack on June 21, 1942.

Into captivity went Tobruk’s garrison commander, South African Maj. Gen. Bernard Klopper, 13,400 South African soldiers, 2,500 Indians and Gurkhas, and 19,000 British soldiers and sailors. Only a thousand or so of the garrison managed to escape to rejoin the British Eighth Army, falling back on Mersa Matruh 220 miles to the east and well inside Egypt. Popski’s Private Army, led by Lt. Col. Vladimir Peniakoff (nicknamed “Popski”) and the smallest of the British special forces detachments operating in the desert, assisted some of the escapees in getting out of Tobruk. Many months later, while operating behind the German lines in Italy, Popski and his Private Army rescued General Klopper who had escaped from a POW camp and was, in Popski’s words, “wandering around.”

Opening the Way to Egypt

Rommel’s victory was given huge publicity in Germany and Italy. Rommel, the headlines blared, had opened the way to Egypt, to Alexandria, Cairo, the Suez Canal, and beyond. Hitler promoted him to field marshal, and Mussolini flew to Tripoli with his white horse and dress uniforms to lead the Italian troops in a victory parade in Cairo.

Three days later, June 24, using trucks, gasoline, oil, ammunition, and food captured at Tobruk and the Beau Geste-style Fort Capuzzo, Rommel advanced on Mersa Matruh where the severely mauled Eighth Army had halted its retreat and was preparing to make a stand. At this point, the British Commander in Chief Middle East, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, assumed personal command in the field. He decided not to fight for Mersa Matruh and ordered the Eighth Army to begin an immediate withdrawal to El Alamein. That evening, Rommel launched his attack on Mersa Matruh.

The New Zealand Division, encircled by panzergrenadiers on an escarpment south of Mersa Matruh and without armored support, broke out in a wild night attack with fixed bayonets, yelling Maori war cries and killing grenadiers as they tried to surrender. Almost 10,000 New Zealanders broke through and got away, but when the battle for Mersa Matruh was over the Germans held another 6,000 unwounded Eighth Army prisoners.

Rommel drove relentlessly after the tired, scattered Eighth Army in what became a race for El Alamein, 109 miles eastward along the coast. El Alamein for Rommel was “the last obstacle to our advance on Alexandria. Once through, our road to the Nile is clear.” For Auchinleck, El Alamein was “the defensive position of last resort.” The German and Italian tank crews and infantry, exhausted and running short of the supplies captured at Tobruk, lost the race.

Attacks Through Minefields and Sandstorms

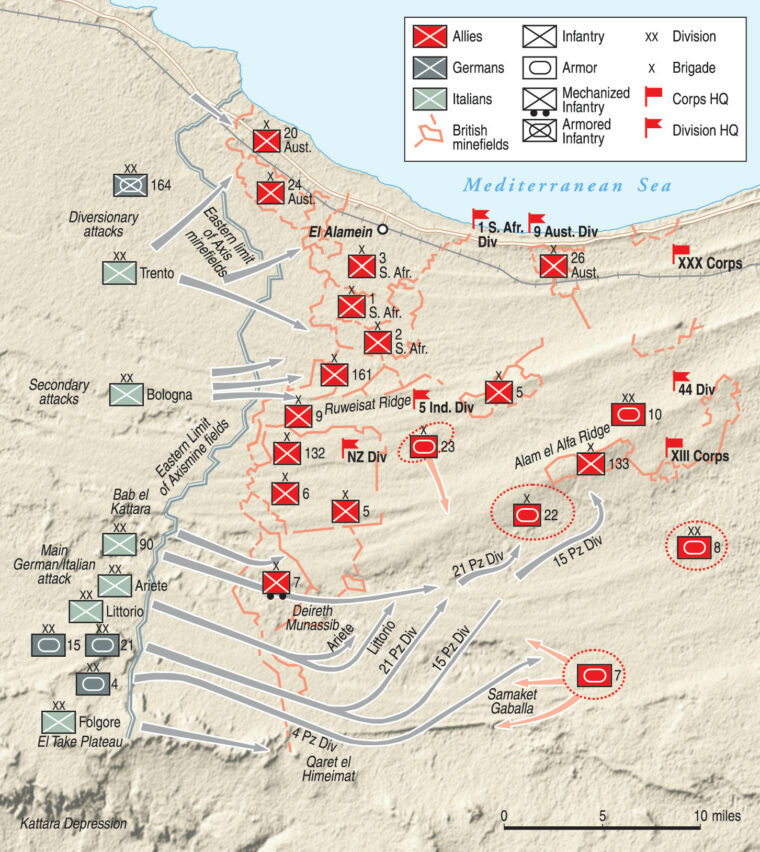

At El Alamein, Auchinleck regrouped his forces, including the recently arrived 9th Australian Division, in a line stretching from El Alamein, an isolated railway station one mile from the sea, 40 miles south to the northern cliffs of the Qattara Depression, a 7,000-square-mile basin of sand-encrusted salt marsh almost impassible for any kind of vehicle. Anchored on the sea to the north and the Qattara Depression to the south, the Alamein line could not be outflanked. Any attack on the line would have to be frontal, denying Rommel’s panzers the advantage of mobility.

Between El Alamein and the Qattara Depression were three low, narrow ridges running roughly parallel with the coast and named from west to east Miteiriya, Ruweisat, and by far the largest, Alam el Halfa. Auchinleck deployed some infantry and artillery on these ridges and set up his forward tactical headquarters on the eastern part of Ruweisat. As there were not enough troops to hold the line continuously, a number of strongpoints, or “boxes,” were set up along the line with most of the armor deployed behind them. German Maj. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein described the whole area as “stony, waterless desert where bleak outcrops of dry rock alternated with stretches of sand sparsely clotted with camel scrub beneath the pitiless African sun.”

On July 1, 1942, the Afrika Korps came up against the British minefields and murderous artillery fire of the Alamein line. In Rommel’s words, “Under such overwhelming weight of firepower our attack ground to a halt.”

The following day, after some reorganization, Rommel attacked again with the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions pushing to the north of the line. Eighth Army armor ducked and weaved, feigned a retreat, and then hit the panzers on their unprotected southern flank. They were soon on the defensive and outnumbered by Eighth Army tanks, and with a sandstorm blowing in, the panzers pulled back.

During the sandstorm, Rommel’s 90th Light Division, which had more armored vehicles and mechanized infantry than tanks, unexpectedly stumbled into the 3rd South African Brigade. In an uncharacteristic display by the veteran division, it panicked and bolted. At the same time, the Italian Ariete Armored Division crumbled under an attack by the New Zealanders, who captured 30 guns and took 400 prisoners.

The Allied Counterattack

When the sandstorm died down, Rommel tried for several more days to break the Eighth Army line, but his attacks were broken up and repelled by artillery and air bombardment. Auchinleck retaliated with several widespread counterattacks. His targets were Italian in an effort to force Rommel to use up his armor’s fuel to assist his allies. On the fifth day, Rommel ordered a pause to rest his exhausted troops and to absorb German infantry reinforcements being flown in from Crete. He intended to return to the attack, but Auchinleck beat him to it.

During the first six months of 1942, the U.S. military attaché in Cairo had been sending regular, comprehensive reports on the British order of battle and British intentions to Washington in a code that German intelligence had broken. It had been a valuable source of information for Rommel until the leak was discovered by ULTRA intercepts and was plugged. Without advance notice of British intentions, Rommel was now obliged to fight his enemy on a more equal footing.

At 5 am on July 10, Auchinleck’s guns opened up in a heavy bombardment of the northern end of the front. This was followed by an attack astride the coastal road by the 9th Australian Division. The Australians put the Italian Sabratha Division to flight, taking 1,550 prisoners, and on Tel el Eisa, the Hill of Jesus, they captured Rommel’s 100-strong Wireless Reconnaissance Unit 621. This mobile radio interception station had been picking up reports from German spies in Cairo and eavesdropping on British military radio communications. The tactical intelligence collected was of vital importance to Rommel and its loss was another serious blow for him. For the British it was a bonus; they put the radios and other equipment to good use.

Rommel was at the southern end of the line when he heard of the Australian attack. He rushed north with part of the 15th Panzer Division to close the gap, and for several days a vicious battle was fought for Tel el Eisa. During one panzer attack, Corporal James Hinson got close enough to a leading tank to take it out with a “sticky” bomb he attached to it. Hinson was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal. During an infantry assault, Corporal Victor Knight and his four Vickers machine guns held off an attack for three hours, the infantrymen urinating on the gun barrels to cool them and pouring oil into the working parts, keeping the guns firing continuously. The Germans, the 104th Infantry Regiment recently arrived from Crete, sustained 600 casualties, more than 50 percent of their number, from the machine guns and some shellfire during the attack. Knight, too, was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal.

Rommel’s Worst Days

On July 14, savage fighting erupted around Ruweisat Ridge, held by the New Zealanders, when it came under attack by the 15th Panzer Division and the Italian Brescia Infantry Division. Fighting continued into the next day. In one action, Captain Charles Upham was awarded his second Victoria Cross. He was wounded twice while leading a night attack against mechanized infantry and got close enough to a truck filled with panzergrenadiers to kill most of them with grenades. He was wounded again but took part in another attack at dawn.

Four machine-gun posts, supported by tanks, held up the attack, and Upham charged. Wounded yet another time, he was captured. He made several attempts to escape and ended the war in Colditz Castle, the Germans’ highest security prison. He was only the third man in the history of the Victoria Cross to receive it twice, and the only one to survive. When the battle for Ruweisat Ridge ended the New Zealanders remained in possession of it.

Around this time the British mounted several strong attacks, severely mauling the Italian Brescia, Trieste, and Pavia Infantry Divisions and forcing German armored units to use scarce fuel in coming to their assistance. On July 17, Rommel wrote to his wife, “It is going pretty badly for me. The enemy’s superior infantry is taking out one Italian unit after another. German units much too weak to halt them alone. It makes me cry!” And on the following day he wrote, “The past, crucial day was particularly bad for us. Once again we got away. It cannot go on much longer or the front is lost. Militarily these are the worst days I have lived through.”

By now, Rommel had committed his last reserves, including elements of the new 164th Infantry Division, which was still being formed. To keep the pressure up, Auchinleck threw in the 23rd Armored Brigade, only recently arrived from England. It had done little desert training, and its Valentine tanks, although heavily armored, were armed with only the old, inadequate two-pounder gun. In Balaclava style, the brigade charged the veteran 21st Panzer Division, screened by antitank guns, and in an hour 86 of its 97 Valentines were destroyed.

The Threat of Mutiny

Auchinleck was now faced with another problem—a high-level mutiny. Both Australian commander Maj. Gen. Leslie Morshead and New Zealand commander Maj. Gen. Bernard Freyberg had long been dissatisfied with the performance of the British armor. More often than not, they said, “the tanks had difficulty coordinating with the infantry—they turned up at the wrong place or the wrong time, or didn’t turn up at all. They disappeared from the battlefield long before midnight saying they couldn’t see in the dark, leaving the infantry without tank cover. When they did attack they often attacked ‘unscientifically,’ for example, as had the 23rd Armored Brigade.” So now Morshead was declining to attack on the grounds that he had no confidence in the armor and if ordered to do so he would have to consult the Australian government.

Auchinleck managed to placate the Australian by offering him British troops for the most dangerous part of the next offensive, and Morshead finally agreed. Freyberg, too, decided to let the matter rest. The British troops given to Morshead were one of 50th Division’s tired brigades that had been in action continuously for over three months.

On the first night of the offensive the British brigade lost 600 men killed or captured, and one Australian battalion was surrounded by panzers after its tank support was driven off with heavy losses. As the panzers closed in, an Australian soldier ran forward, spraying a tank with bullets from his .303 Bren gun. The bullets were useless against the tank, and the soldier was shot down. His action convinced the battalion commander of the futility of resistance, and he signaled the battalion to end the hopeless fight.

The next day, Auchinleck called off the offensive, ending the battle in a stalemate. Both sides were exhausted. But for Auchinleck, it was, in a sense, a victory. The Afrika Korps had been stopped cold, and 7,000 prisoners, mostly Italian, had been taken.

Montgomery Takes Command of the Eighth Army

During July and August, Rommel received some 24,000 troops and 11,000 Luftwaffe personnel airlifted in by Junkers Ju-52 transports. However, these reinforcements had no artillery or other heavy weapons, no troop carriers, tanks, or ammunition. They, in fact, imposed a greater strain on his overstretched transport and supplies. Among the reinforcements was a brigade of paratroops commanded by Maj. Gen. Bernhard Hermann Ramcke. It comprised four battalions of paratroopers and support units, 4,000 men in all, a tough, hard-hitting force that was soon in the thick of the heaviest fighting.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill flew into Cairo on August 3, and, intent on a shakeup of his top military commanders, visited them in the field. He replaced Auchinleck with Lt. Gen. Sir Harold Alexander as commander of a new Near East Command, and placed Lt. Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery in command of the Eighth Army.

Montgomery arrived at Eighth Army headquarters on Ruweisat Ridge on August 13, where his chief of staff, Brigadier Francis de Guingand, had assembled all his staff officers. Sitting in the sand, they listened to this small, wiry man who “looked more like an ops room clerk than an army commander.” His message was short, simple, and electrifying: There would be no more surrender.

“There will be no further withdrawal,” stated Montgomery. “I have ordered that all plans and instructions dealing with further withdrawal are to be burnt, and at once…. The Eighth Army will not yield a yard of ground to the enemy…. Troops will fight and die where they stand…. We will start to plan a great offensive; it will be the beginning of a campaign which will hit Rommel for six right out of Africa.” He was doing what all effective leaders do—defining and focusing on the task of finishing Rommel. He was also building a team by creating mutual confidence.

Montgomery knew that “generations of taking war seriously had given the Germans a superiority in standard operating procedures, command and control and staff work, and an instinct for battle so great that the only way they could be defeated was by ruthless attrition.” He planned accordingly.

Montgomery Reorganizes the Defense

Anticipating that Rommel’s next attack would be at the southern end of the Alamein line and aimed at Alam el Halfa Ridge, Montgomery brought in a newly arrived infantry division, the 44th, with its antitank guns and artillery, to reinforce his units already on the ridge. Most of his tanks, including 170 American-made Grants with their 75mm guns, were dug in around the ridge, hulls down so that only their turrets were exposed. The tanks were under strict orders to stay put, to stand and fight. There would be no more heroic cavalry-style charges as had happened so often in the past with devastating results. From now on the Eighth Army would play it Monty’s way, not Rommel’s.

Montgomery knew from ULTRA that Rommel was desperately short of supplies, especially fuel. The main ports along the North African coast, through which Rommel could obtain supplies from Italy and Greece, were Tripoli, 1,300 miles from El Alamein; Benghazi, 800 miles away, and the still-distant locations of Tobruk at 300 miles and Mersa Matruh at 109 miles. The British Desert Air Force mauled German convoys, bombed and strafed targets in Tobruk and Mersa Matruh, and attacked supply ships. British submarines also took their toll on Axis shipping. Only a small percentage of the supplies sent were reaching Rommel.

In stark contrast, for the Eighth Army, El Alamein was only 60 miles from the port of Alexandria and 150 miles from the Suez Canal where 100,000 tons of fuel alone were being unloaded each month. As a veteran desert warrior remarked, “War in the desert is ultimately about who has the better lines of supply.”

A Slow Armored Advance

For his next attack on the Alamein line and a breakthrough to Alexandria and Cairo, Rommel planned a feint attack in the center of the line while his armor would outflank British positions in the south, then wheel north and head for the sea, encircling British forces in their positions. They would then head east, for Alexandria. Rommel believed that Egyptians would welcome him and turn against the British. An integral part of the operation involved the Ramcke Parachute Brigade which, with the Italian Folgore Parachute Division, would parachute near the Nile and capture the bridges at Alexandria and Cairo. The plan did not fully materialize.

When he spoke to his officers on August 13, Montgomery had said, “I understand that Rommel is expected to attack at any moment. Excellent. Let him attack. I would sooner it didn’t come for a week; it will just give me time to sort things out. If we have two weeks to prepare we will be sitting pretty. Rommel can attack as soon as he likes after that and I hope he does….”

Rommel launched his attack on the night of August 30. With the larger part of the Axis force, including four armored divisions, he raced in a sweeping arc just north of the Qattara Depression to break through the British line and wheel toward the sea. But the British had heavily mined the area, and while German and Italian troops tried to clear passages through the minefields the Desert Air Force lit up the sky with parachute flares and bombed and shot up tanks and the supply trucks coming up behind them. British guns accounted for more.

The following day, the panzers were out of the minefields but still under air attack and faced with the guns and tanks on and around Alam el Halfa. Rommel wanted to call off the attack, but Bayerlein persuaded him to go on, turning east earlier than planned so as to make the drive on Alexandria much shorter and save on fuel. As it was, the armor would soon have to refuel anyway.

It took until 10 am to get the armor moving, but by then a sandstorm was beginning to blow in. By midday visibility was almost nil. The Desert Air Force was grounded, and refueling for the Germans and Italians was an exhausting and nerve-wracking business, but better than being bombed. By 1 pm the tanks had refueled and, with the storm at its height, they began moving slowly northward, toward the western edge of Alam el Halfa where the 22nd Armored Brigade with its Grant tanks and supported by the 23rd Armored Brigade was dug in and waiting.

Progress for the German and Italian armor was painfully slow in soft sand and the blinding sandstorm. Then, at about 5:30 pm, the storm began to abate. As the air cleared, observers on Alam el Halfa saw 120 German tanks emerge from the subsiding clouds about 1,000 yards in front of the 22nd Armored. The tanks then wheeled east, across the British positions, and General Roberts ordered a flank attack. The leading German tanks were new, with long-range guns, and they opened up while they were out of range of the British guns, causing casualties among the Grants. However, they closed in, and the British hit back. Probing for a way through, the Germans edged west, toward presighted antitank guns, which they could not see. The gunners held the fire of their 6-pounders until the range closed to 300 yards, then opened up. There was nothing the German tanks could do but charge. They overran a few of the guns but took losses and could not break through. It was a reversal of Rommel’s tried and tested tactic of show and kill, which had so often in the past lured British tanks to their destruction. When dusk came, Rommel withdrew a few miles. Both sides had lost more than 20 tanks in the action, and both sides worked at reclaiming and repairing the many that were damaged.

Rommel’s Defeat at the Battle of Alam el Halfa

That night, Montgomery ordered the bombing of German and Italian supply transports, hitting Rommel where it hurt. The next morning, September 1, Rommel was further frustrated when the British tanks did not try to attack him. He attempted another push on the ridge, hoping to lure the British tanks out, but they did not move. He then withdrew into the desert where he was bombed all day. He subsequently decided to retreat but had to wait until nightfall to do so. He then fell back in good order, and by the evening of September 6 had returned his forces to the safety of their own fortified line.

From now on, Rommel was doomed to a battle of attrition, a battle he knew he could not win. His only gain in territory was the Himeimat Ridge in the far south, and at 1,300 feet it was a wonderful observation post for the Folgore. Montgomery was happy to leave the Germans there; he said it suited his purposes “that Rommel should be able to have a good look” at the dummy installations he was preparing to set up in the south to confuse the Germans as to the direction of the next British attack.

Casualties in the battle of Alam el Halfa were about 1,750 for the Eighth Army and about 2,800 for the Germans. The Afrika Korps had lost 47 tanks and recovered 76 that had been damaged. It had lost some 400 other vehicles, mostly by bombing, a serious blow to the movement of troops and supplies.

Some high-ranking German officers blamed Rommel for the defeat at Alam el Halfa, saying that once the panzers had gotten through the minefields and outflanked the British the old Rommel would have pressed on. Others accused him of allowing himself to become demoralized by his fears of fuel shortages after the sinking of several Italian oil tankers in the Mediterranean. On the other hand, if he had pressed on at Alam el Halfa he might have lost all his armor in useless frontal attacks.

Generals as Celebrities

Rommel was also a sick man, suffering from stomach and liver complaints complicated by high blood pressure, sinusitis, and a sore throat. On September 23, he handed over command of the Afrika Korps to General Georg Stumme, a veteran Panzer commander of the French and Russian campaigns, and left for Germany on sick leave. He was greeted as a national hero.

Rommel was also a heroic figure to many in the Eighth Army, and Montgomery looked for a way to improve his own image. He had begun wearing an Australian issue Digger’s hat studded with the badges of various regiments, but it tended to fly off when he stood up in the turret of the tank he had adapted for use as his mobile tactical headquarters. He changed it for a black Royal Tank Corps beret adorned with the Tank Corps badge and a general’s insignia. He also had the name “Monty” painted in large letters on the side of his tank, a rather dangerous thing to do.

Montgomery was determined not to launch an offensive against the Afrika Korps without the intensive training and retraining of both newcomers to and veterans of his Eighth Army. So, though Prime Minister Churchill (who wanted an offensive mounted in September before the planned Allied landings in Morocco and Algeria) fumed at the delay, Montgomery refused to move until he was sure his army was ready and he was confident of a victory.

Building a British Bloodlust

While working on his plans, Montgomery rotated brigades out of the line and put them through various training courses based on what he expected to happen in reality. Vigorous physical training, mine clearing, tanks and troops working together, the use of creeping barrages, communications, night attacks, and cooperation with the Desert Air Force were part of the regimen. He also worked on camouflaging the buildup for his offensive to achieve maximum surprise on the date he had set, a date he was keeping secret.

At the southern end of the Alamein line, dummy headquarters buildings, barrack tents, and supply dumps with empty fuel cans were set up. Fires were lit at night to suggest a major troop concentration, trenches and gun emplacements were dug, and imitation minefields laid, while the Desert Air Force deliberately allowed German reconnaissance aircraft to photograph the activity. Mock tanks were set out, a dummy water pipeline made from empty oil drums was constructed, and signalers kept up a steady flow of coded radio traffic between bogus divisions.

In the north, similar dummy positions were laid out while the fighting divisions were kept well to the rear. As the deadline for the attack approached, the fighting divisions were filtered into their positions and dummy vehicles and supply dumps were replaced with the real thing.

As the date Montgomery had selected to begin his attack approached, he issued an order to his officers telling them to promote a bloodlust among their men, saying, “They must be worked up to that state which will make them want to go into battle and kill Germans, even the padres who could kill Germans one on weekdays and two on Sundays.” Montgomery was the son of a bishop.

Half a Million Mines

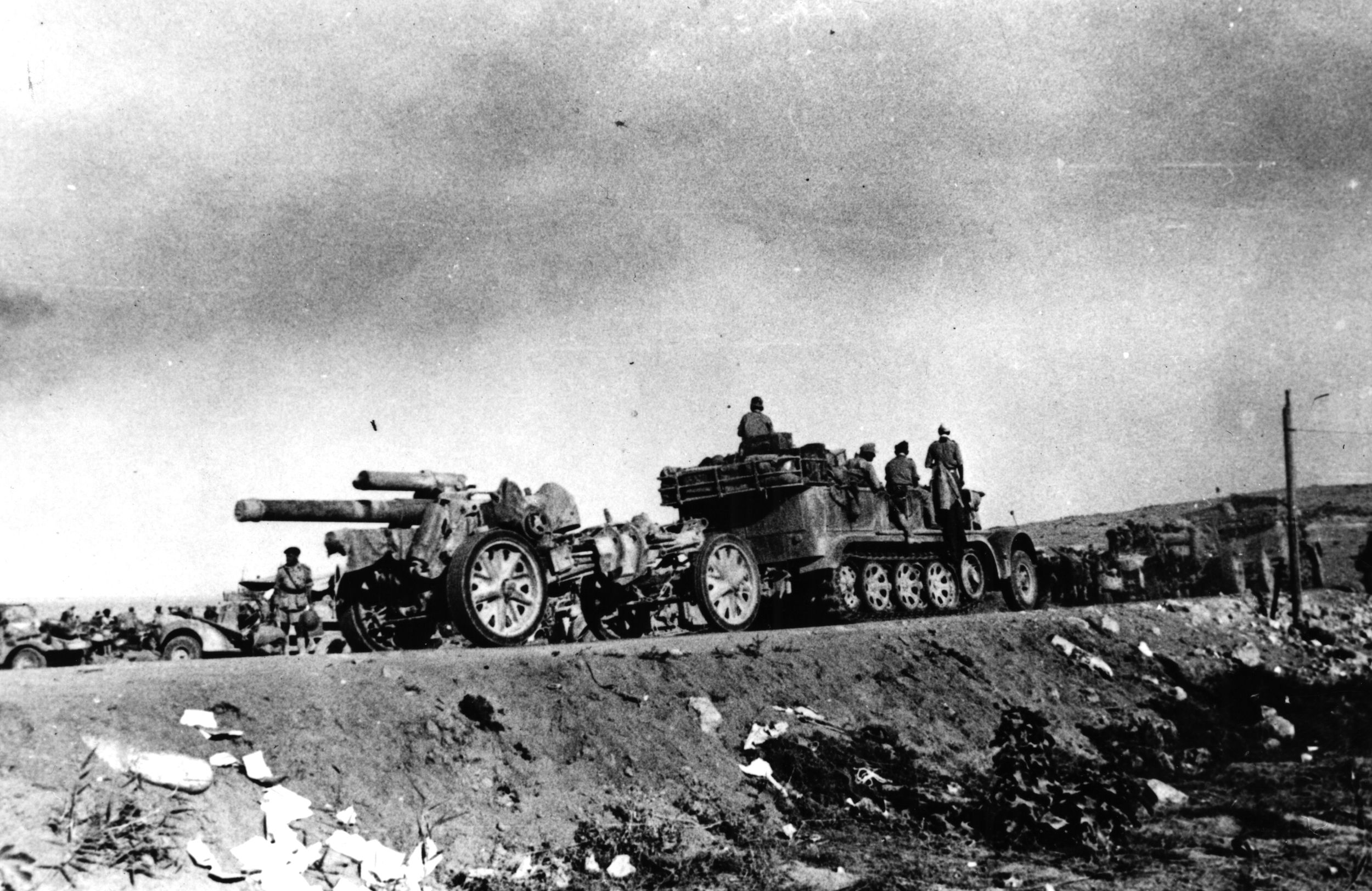

Before leaving for Germany, Rommel had laid the foundations for a formidable defense. It was based on a half million mines, a mix of antitank and antipersonnel mines in two enormous fields a mile apart. The minefields were covered by artillery and machine guns, and behind them the deadly 88mm cannon and other antitank guns.

The front was manned by infantry: the 164th Light and Trento Divisions in the north; Bologna, Ramcke’s Parachute Brigade, and Brescia in the center; Pavia and Folgore Airborne in the south. Behind them were the armored divisions divided into six groups, three formed by 15th Panzer and Littorio in the north and three by 21st Panzer and Ariete in the south. At the far south of the Axis line was the German Kiel Group, equipped with captured Stuart light tanks. The reserves, the veteran motorized 90th Light and Trieste Divisions, were three miles behind the front and close to the coast in case Montgomery tried an amphibious landing to the rear. In all, the Axis force consisted of about 50,000 Germans and 54,000 Italians. They had about 500 tanks, 280 of them inferior Italian models; some 1,200 artillery pieces, half German and half Italian; and about 350 aircraft, not counting those available from Crete, Greece, and Sicily.

The Eighth Army’s Three Corps

The reinforced Eighth Army had 195,000 men, just over 1,000 tanks, 2,300 artillery pieces, and some 530 aircraft of the Desert Air Force. It consisted of 19 Royal Air Force, nine South African, seven American, and two Australian squadrons. Some RAF squadrons had the latest Supermarine Spitfire fighters, while the U.S. squadrons flew primarily the North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber and the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter. The Desert Air Force was now in almost total control of the air, and it worked extremely well with the Eighth Army. Montgomery worked feverishly to make his Eighth Army “think on its tracks and wheels and react quickly, and to weld infantry, antitank guns, artillery, armor and air power into one controlled and seamless killing machine.”

Monty divided the Eighth Army into three corps, numbered 30, 13, and 10. The first two were mainly of infantry, while 10th Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Herbert Lumsden, was made up of tanks, armored cars, and the truck-borne infantry of two armored divisions.

Montgomery divided the front into northern and southern sectors at the Ruweisat Ridge. In the northern sector was Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese’s 30th Corps with Morshead’s Australians nearest the coast; then, moving south, Maj. Gen. Douglas Wimberly’s 51st Highland Division, Freyberg’s New Zealand 2nd Division, Maj. Gen. Dan Pienaar’s South African 1st Division, and Maj. Gen. Francis Tuker’s Indian 4th Division. All these Commonwealth divisions had a certain amount of British armor attached to them, the New Zealanders an entire brigade. The 4th Indian Division included three battalions of British infantry. The artillery and support arms were almost entirely British, and in reserve was the 23rd Armored Brigade, which included a battalion of motorized infantry. Behind these in the northern sector were the 1st and 10th Armored Divisions of Lumsden’s 10th Corps.

In the southern sector, Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks’s 13th Corps included Maj. Gen. Nicholl’s 50th Division reinforced with a brigade of Free Greeks and Maj. Gen. Hector Hughes’s 44th Division. Farthest south in the line was Brig. Gen. Marie-Pierre Koenig’s Free French Brigade, the heroes of Bir Hacheim. Behind them was the 7th Armored Division, the original Desert Rats, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Harding.

Confined as he was to a 40-mile front, Montgomery’s plan for his assault on the enemy was quite simple. He would attack simultaneously in the north and the south, making it hard for Rommel to ascertain the direction of the main effort, which would be in the north where 30th Corps would break the Axis line between the Miteiriya Ridge and the sea and clear a bridgehead. The 10th Corps would then pass through them and engage the armor of the Afrika Korps on the plains beyond. In the south, 13th Corps would capture Himeimat and thereby threaten Rommel’s flank, forcing him to commit his armored reserves to plug the gap. At the same time, part of the 7th Armored Division would attack his supply dumps.

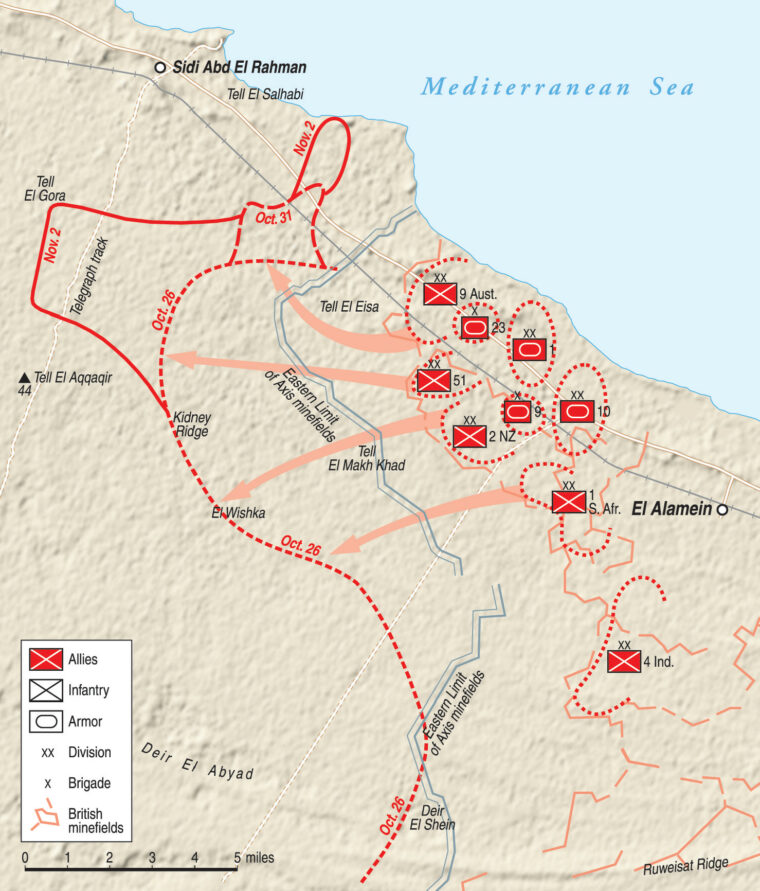

Montgomery’s date for the beginning of his offensive was October 23, and for all of that day the frontline troops in the northern sector lay hidden in their trenches and foxholes under the desert sun. After dusk, in the early chill of a cold desert night, the troops were allowed out of their holes to eat and smoke and, if lucky, to sip a little rum from large stone bottles that were passed around. Since the days of Admiral Horatio Nelson a regulation tot of 90 proof navy rum had been issued daily to sailors on His or Her Majesty’s ships, but only on very special occasions was it issued to soldiers. A tot, a serving spoonful, was estimated to be enough to maintain morale without losing coherence. At 9 pm, in full moonlight, the infantry divisions moved to their start lines and waited in complete silence.

The British Advance Begins

At 9:25, in the southern sector, 230 British guns opened up in a bombardment of the German defenses. At 9:35, all along the line there was the sound of approaching bomber squadrons of the Desert Air Force, and at 9:40 the ground shook and the air vibrated as a 460-gun artillery barrage opened up in the northern sector, mixing with the crash of bombs from the planes passing overhead.

The artillery barrage and the bombs were aimed at enemy artillery batteries, and an intense rate of fire was kept up for 15 minutes. Then there was a pause for five minutes. At exactly 10 pm, the guns opened up again with a rolling barrage on all of the enemy’s forward positions at the rate of 900 rounds per minute. Acres of mines were blown up, blockhouses and dugouts caved in. German and Italian soldiers were deafened for hours, their ears bled, and some dropped dead from the concussion of the exploding shells.

As the barrage rolled forward, the infantry divisions in the northern sector of the line fixed bayonets and began their advance, the 51st Highland Division with bagpipes skirling. Piper Duncan McIntyre, age 19, his Royal Stuart kilt swinging, led the 5th Black Watch to the first ridge. Twice he was wounded, but he continued skirling out “Highland Laddie” until a burst of machine-gun fire silenced him forever. The job for the Highlanders that night was to open up two corridors through the enemy minefields and defenses. Bofors antiaircraft guns fired tracers above their heads to mark the lines of advance cleared by sappers and flail tanks through the minefields.

The Australians and Highlanders, with the assistance of three regiments of tanks, were to clear a path through the positions held by the 164th Light and Trento Divisions so that the 1st Armored Division could pass through. The Australians struck into the area west of Tel el Eisa. The northern brigade of the division took its first objectives by midnight and, after some hard fighting, took its final objectives by 2:45 am. The southern brigade was still 1,000 yards short of its final objectives when dawn broke, so the troops dug in. Casualties were only about 350.

The Highland Division’s task was to extend the northern corridor down from the Afrika Korps strongpoint at Kidney Ridge to the northwest corner of Miteiriya Ridge, the strongest part of the defenses. After crossing the first minefield the troops came upon barbed wire entanglements and, as they cut the wire, machine guns opened up on them. Men began falling, and platoons and companies mingled and bunched up and lost direction. The supporting tanks ran into minefields. In spite of the chaos that ensued, the northern brigade captured some of its objectives though the southern brigade was short of all its objectives. The infantry now became pinned down by fire from some of the enemy strongpoints. The 51st had taken 1,000 casualties.

The Fight for Miteiriya Ridge

The Trento and 164th Divisions held the Miteiriya Ridge. The New Zealand Division, supported by the 9th Armored Brigade, attacked the northern half of the ridge, and the South Africans, supported by a regiment of Valentine tanks, attacked the southern half. The New Zealand northern brigade, after some heavy fighting, had reached all its objectives by 2:45 am and linked up with the Highlanders. They then found more minefields and had only just cleared them by sunrise. The southern brigade also got across the ridge by dawn, but its supporting tanks were held up by mines and gunfire and stayed on the eastern slope of the ridge, with the infantry out in front of them without heavy weapons. They had bunched toward the north, leaving a gap to the south between them and the South Africans. The New Zealanders had lost about 800 men.

Although held up by heavy resistance at the beginning of their attack, the three South African brigades got onto the ridge and captured their objectives by dawn—except for the brigade to the north; it was 500 yards short. South African losses were 350.

The Indian Division, at the southern end of the northern sector, carried out a number of diversionary attacks on the Italian infantry and German paratroopers on Ruweisat Ridge, helping to keep the enemy unclear as to the intentions of the Eighth Army.

The Deadly Lanes Through the Minefields

The problem on the northern sector of the line was that the engineers and sappers, taking casualties in the moonlight from artillery and machine-gun fire, had been unable to keep to the timetable of mine removal. Mine detectors and flail tanks were in their infancy and unreliable, and the task of detecting and lifting mines was mainly left to probing with bayonets. Most of the mines were teller antitank, and mixed in with them were antipersonnel mines, which, when exploded, threw out a ring of ball bearings at waist height. The minefields were covered by artillery and machine guns, many of the machine guns fixed to fire at knee height.

Once a lane had been cleared through the mines, it became congested with tanks and vehicles waiting for lanes ahead to be cleared, and the tanks and vehicles were sitting targets in the moonlight under German parachute flares. In the swirling sand and dust, tanks ran over the tapes marking the lanes, and some veered off into the minefields while others stopped, not knowing where to go. Soon it became a vast traffic jam, and the ammunition and fuel trucks, artillery, ambulances, and other vehicles stretched back for miles. The sun came up to fully reveal this huge mass of vehicles in choking sand and dust clouds.

The Death of General Stumme

In the southern sector of the line, the role of 13th Corps was to look threatening enough to persuade Rommel to keep his 21st Panzer Division and other units in the south. To do this, Horrocks sent his 7th Armored Division into the attack, with the infantry following, at the same time as the northern sector infantry began their advance. The infantry attack comprised the 44th and 50th Divisions, the Free French Brigade, and the 1st Greek Infantry Brigade.

After some delays, mainly because of the breakdowns occurring with several of the flail tanks, a path was cleared to attack the positions of the Folgore Parachute Division, and the Free French moved through to take the two peaks of the Himeimat. But the German Kiel Gruppe counterattacked and pushed them off. The French, mostly Foreign Legion men, were demoralized by the death of one of their most flamboyant officers, the Russian prince Colonel Dimitris Amilakvari. The Kiel Gruppe, on the Himeimat, played havoc with the advancing 13th Corps armor and infantry. When dawn came, the infantry dug in and the Folgore Airborne and some of Ramcke’s paratroopers closed in.

The Eighth Army’s opening artillery barrage and bombing had destroyed many of the Axis guns and disrupted communication links between army, corps and divisional headquarters. Runners were used to carry some messages, but no one knew very much about what was going on. The German commander, General Stumme, set off in the early morning for the front line in a car with a driver and staff officer to assess the situation. Under fire from Australian machine guns, the staff officer was killed and Stumme was stricken by a fatal heart attack. The driver, though wounded, managed to get Stumme’s body back to his headquarters. Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, commander of the Afrika Korps, took over as commander of the entire panzer army until Rommel returned.

The 10th Corps Stalls

By dawn on October 24, the Australian, British, New Zealand, and South African infantry of 30th Corps had achieved some of their objectives along the line codenamed “Oxalic,” but by 8 am only about half of them were where Montgomery had wanted them to be. Nevertheless, they had hammered a huge wedge in the enemy’s defenses. Casualties had been relatively few, mainly wounds from mines and booby traps.

Behind the infantry, 10th Corps armor had performed badly, failing to exploit the infantry’s successes. Nowhere had they broken through the enemy defenses to establish a tank screen to protect the infantry from the panzer divisions massed to counterattack. Much of 10th Corps’ armor was stuck in the minefields or in the clogged lanes through them. They had not carried out Montgomery’s order that if the infantry was held up they should drive through them and attack. The British commander was furious. He saw it as a lack of determined leadership and offensive spirit in his armor, and he threatened that if the armored division commanders hung back any more he would replace them with better men.

During next day, on both fronts, one soldier said, “It was dangerous to lift your head, suicide to stand up,” and casualties were heavy. That night, in the northern sector the tanks tried to get through the minefields to the infantry, but German 88s and mines took out so many of them the attempt was called off. In the southern sector, Maj. Gen. John Harding withdrew his tanks and infantry—he had been ordered to conserve his tanks for a future action—leaving Ramcke’s paratroopers and the Folgore Airborne on Himeimat. This was intentional; Montgomery wanted the Germans to think he might still make his major attack in the south.

Getting the wounded back from areas under shell and machine-gun fire was a hazardous business for the Eighth Army medics and many others who helped. They were assisted by a band of American Red Cross volunteers who drove four-wheel-drive Dodge trucks back and forth under fire, leaving British medical officers and soldiers with, as one medical officer said, “fond memories of a gallant and eccentric breed.”

The Battle for Kidney Ridge

Rommel returned and took up command of the Axis forces at midnight on the 25th, more than 48 hours after the battle had begun. With his return, morale rose in all the ranks of the army. He inherited a front on which the Eighth Army had severely dented the northern part of his line, but nowhere had the British succeeded in driving a hole through it. Most of the Eighth Army’s armor was still stuck behind the infantry, and the Germans and Italians were putting up a stiff resistance.

Rommel quickly realized that Montgomery was feinting in the south and that his main attack was nearer the coast. He ordered the 21st Panzer to move north toward Kidney Ridge. It was a risk; it left him with only the Ariete Division in the south, and if Montgomery decided to move his armor in that direction Rommel would not have enough fuel to send his panzers back to help the Ariete.

But Montgomery was sending his infantry and armor from the south to the north, around Kidney Ridge, where an all-out battle was developing with the Highlanders and Australians fighting for the position. Early in the battle the 15th Panzer and the Littorio Armored Division with its “wretched M13 tanks” began an all-day attack on the ridge. One regiment of the Littorio had its 41 tanks quickly reduced to two. An Italian officer described what happened: “Some of the tanks continued to advance even after they had been hit and set on fire, with only dead and dying men inside them, like huge self-propelled funeral pyres, a dead man’s foot still pressing down on the accelerator…. A procession of blazing monsters, shaken by explosions and emitting colored flashes as the shells inside went off…. The souls of the dead men must have been trapped in their vehicles; how else could a smashed and blazing tank continue to advance towards the enemy?”

The battle continued with heavy losses on both sides in men and tanks, six days of non-stop attack and counterattack. Then Montgomery withdrew his tanks, and with both sides exhausted the battle petered out in stalemate. More than 2,000 of the Highlanders were dead or wounded, and well over 1,000 Australians, but the Australians had gotten “a thumb” across the railway line. If they reached the sea, they would trap Rommel’s 90th Light and 164th Divisions in a pocket.

Codename Supercharge

Montgomery had already planned his next attack, codenamed Supercharge. New Zealand commander Bernard Freyberg would lead five battalions—three from the Durham Light Infantry and two from the Highland Division— together with one battalion of his Maoris and, supported by the tanks of the 9th Armored Brigade, and punch a corridor through the minefield to just north of Kidney Ridge in the vulnerable junction where the German and Italian defenses met.

At 1 am on November 2, the six battalions of infantrymen fixed bayonets and began walking forward behind a creeping barrage that advanced 100 yards every three minutes and fell on and exploded hundreds of mines. Bofors antiaircraft guns with barrels lowered fired tracers above the heads of the infantry to help the battalions stay on course. Shortly before dawn, the infantry had seized most of its objectives. The 9th Armored Brigade, for various reasons, started late, at 6:15 am. Close to the front, the tanks had to feel their way under artillery fire along narrow channels cleared through the minefields. When the sun came up behind the tanks, they were easy targets, and soon plumes of smoke rose up from the burning wrecks.

Still, the armor pushed on in a frenzy, in a charge often compared with that of the Light Brigade at Balaclava, reaching the enemy’s anti-tank and field guns, driving over guns, gun pits and gunners. Some of the armored cars of the Royal Dragoons charged through the enemy lines and began shooting up fuel dumps, transports, and other soft targets. In this charge, the brigade lost 270 men killed or wounded and 71 of its 90 tanks.

The 2nd Armored Brigade failed to take advantage of the hole punched through the enemy antitank gun line, and then it was too late. Rommel, realizing what was happening, reacted quickly, moving the 21st and 15th Panzer Divisions to block Montgomery’s move, and the largest tank action of the battle began to build up on the Rahman track around Aqqaqir.

The 2nd Armored Brigade and the remnants of the 9th bore the brunt of the initial fighting, but soon more and more British armor was drawn into the battle. By the end of the day, Rommel had less than 50 tanks able to move while Montgomery had some 500. Rommel was also short of antitank guns; he had only 24 88mm guns left to face the British tanks in the salient Freyberg had created. That evening, Rommel sent a message to the Commando Supremo in Rome, saying that his only hope was to “extricate the remnants” of his army. He warned that his Italian formations, without transport, would have to be abandoned. The British picked up the message via ULTRA, as well as one that followed the next day. This was a communication from Hitler ordering Rommel to stand and fight, victory or death. It was a death sentence for the army, and Rommel understood it as such.

The Axis Retreat

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Commander in Chief South (although he did not have direct authority over Rommel), intervened on Rommel’s behalf and got Hitler’s order rescinded on November 4. That day, the Afrika Korps (the two panzer divisions plus the 90th Light) commander, von Thoma, was taken prisoner when his command tank was hit and disabled. He formally surrendered to Montgomery.

The panzer army front collapsed as Germans and Italians began to fall back, pursued by the Eighth Army. In the southern sector the Folgore Airborne Division, having fought well and now out of ammunition, surrendered. Only 306 paratroopers were left of an original complement of 5,000. The infantrymen of the Pavia and Brescia Divisions quickly joined them. Others began the long walk back, and many died from their wounds, hunger, or thirst or were picked off by Senussi tribesmen for their weapons and anything else of value.

Ramcke’s parachute brigade, which had been involved in heavy fighting during the battle, was abandoned as it had no transport and was unable to join the retreat. Ramcke, rather than surrender, decided to break out to the west. The breakout cost him 450 men, but by a stroke of luck he captured a British convoy of 50 trucks carrying supplies. Using them, the brigade made a hazardous drive across the desert to rejoin the retreating panzer army at Mersa Matruh. Only 600 of the brigade survived.

In the northern sector, the British 22nd Armored Brigade cut off the remnants of the Ariete Armored Division. Twenty-nine tanks and numerous other vehicles were destroyed and 450 prisoners were taken. The 8th Armored Brigade reached the coast and destroyed 40 Italian tanks and six panzers. By then, the Axis forces were in full flight.

El Alamein: “The End of the Beginning”

The Eighth Army’s total casualties were 13,500 killed, wounded, or missing, about eight percent of the force engaged. Most were in the northern sector. The Australians, who at the opening of the battle were tying down the bulk of the panzer army, suffered 2,827 casualties; the 51st Highland Division 2,495; the New Zealanders 2,388; and the South Africans 922. Among the Germans and Italians, 30,000 out of a total of just over 100,000 were taken prisoner, 10,000 of them Germans. Perhaps another 20,000 were killed or wounded. There are no accurate figures.

On Sunday, November 15, 1942, church bells rang out all over Britain, ringing for the first time in the three years since war began, to celebrate the first victory over a German-led army—the victory at El Alamein. Prime Minister Churchill said of the victory, “Now is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But perhaps it is the end of the beginning.”

While Churchill was speaking, the Eighth Army was entering the devastated seaport of Tobruk. Ahead of it, Rommel and his panzer army continued their retreat westward, 1,400 miles across Libya, until, in January 1943, they crossed the border into the hills of Tunisia to meet their end in the final battles in Africa. Before the Axis surrender in North Africa in the spring of 1943, Rommel was recalled and given command of Army Group B in France, tasked with preparing to meet the expected Allied invasion of Fortress Europe.

Montgomery commanded the Eighth Army in Sicily and Italy until late 1943, when he was recalled to England and given command of the 21st Army Group preparing for the invasion at Normandy. He was promoted to the rank of field marshal and remains one of the most renowned heroes in British military history. Fittingly, he was invested with the title Montgomery of Alamein.

John Brown last contributed to WWII History with a story on the ordeal of the Mediterranean island of Malta. He hails from Minyama, Queensland, Australia.

My father Albert Edward Warren was a tank and artillery driver from 1939 to the end of World War II he drove Bernard Law Montgomery’s White car in the battle of El Alamein i would love to know where and if i can find information of my fathers years and time through this period hopefully someone can help point me in the direction thanks