By Jeffrey A. Easton

Centuries before the Romans came to dominate the Mediterranean basin, they fought a series of wars against neighboring peoples to establish their hegemony over the Italian peninsula. During this long process, their greatest opponent was the powerful Samnite federation, with whom the emerging Roman majority clashed for more than 50 years. The most crucial of the three Samnite Wars was the second conflict, fought during the last quarter of the fourth century bc. Nearly every spring from 326 to 304, the two sides deployed fresh levies into the field for annual bloodlettings.

Wearing Down the Samnite Federation

Tactically, the Roman and Samnite armies were quite comparable in their abilities, and the Romans hoped to wear down the Samnites by employing a systematic and well-conceived twofold strategy. First, the Romans secured the southern reaches of their homeland, a disputed area that shared a border with the Samnites. The second phase of the Roman policy was to isolate the Samnites geographically, encircling their territory by capturing key objectives. The Romans planned to accomplish this scheme with a blend of military action, colonization, and the extension of Roman citizenship to residents of important Samnite cities. They intended, as well, to manage their resources in a protracted war while entrusting their armies to the capable hands of experienced military men.

The Romans had good reason to feel confident. During the previous 40 years, the armies of the Republic had regained many of the territorial conquests that had been lost after the Gallic sack of Rome in 390 bc. Through a savvy combination of military action and diplomacy, the Romans secured a base of power in northern Latium by reducing many of their Latin-speaking neighbors to dependent status. The Romans also began making advances against cities in southern Etruria, and in 353 they even concluded a treaty with the Samnites. This alliance was based on mutual anxiety over residual Gallic and Etruscan power rather than any particular affinity toward one another.

Origin of Conflict

Despite the delicate treaty that bound them, the Romans and Samnites became rivals within a short time. The two expanding peoples continued to share a volatile border while competing for control of neighboring regions. The Samnites had a strong position in central Italy, controlling a stretch of land from Campania in the west all the way to the Adriatic coast in the east. The people known collectively as the Samnites were actually a loose federation composed primarily of four major tribal groups—the Hirpini, Caudini, Carricini, and Pentri—who were united by their Oscan dialect. Each group maintained local control over its individual settlements through assemblies and an elected chief magistrate called a meddix. For political and military purposes, multiple towns were grouped together into larger units called touto. During a military crisis, the individual sovereignty of the units was suspended and the entire federation fell under the rule of an appointed commander in chief. This generalissimo then coordinated Samnite resources and led federation forces on campaign.

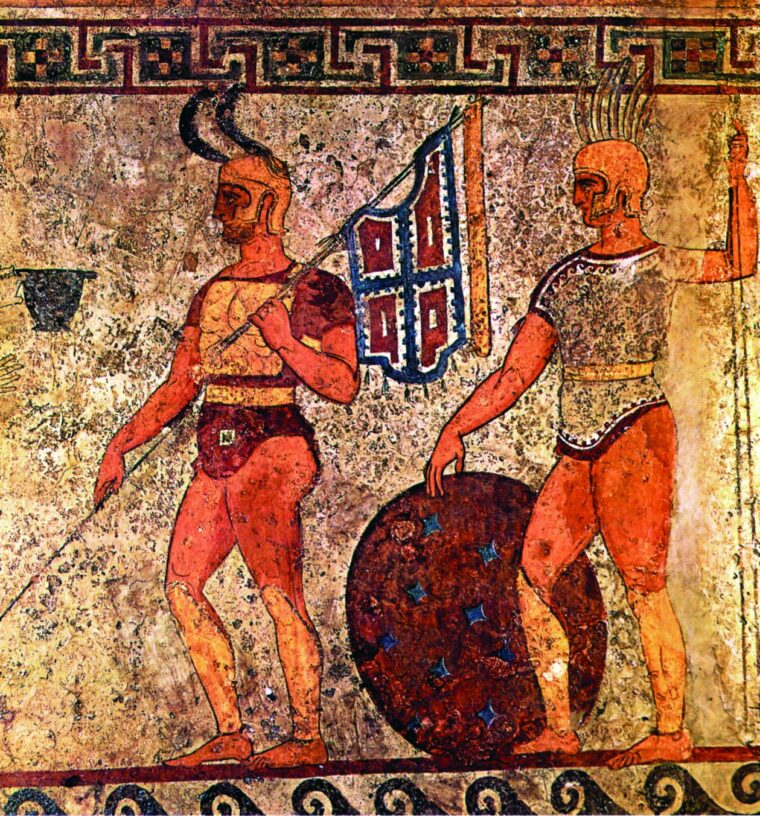

The Samnites were no more disposed toward warfare than any other group in central Italy, but they still appeared to be quite bellicose. As depicted on surviving vases from the fourth century bc, Samnite men shown engaging in a variety of activities are almost always depicted in full military kit. For the most part, the economy and culture of the Samnites were based upon agriculture. They maintained livestock and farmed extensively, but they shared neither the interest in commerce nor the accumulated wealth of their more powerful neighbors, the Romans. For their part, the Romans viewed the Samnites as a rather backward, rustic people living a simple existence. They soon found out, however, that the Samnites possessed the skill necessary to marshal their resources and manpower rapidly and to sustain a conflict over a long period.

The First Samnite War

In 343, Roman and Samnite interests collided and their treaty was broken. The Samnites had begun carrying out raids against the Sidicini, a tribe whose territory lay just beyond the western border of Samnium. The Sidicini looked for help from neighboring Campanian cities, but the Campanian army that took the field to face the invading Samnites was rapidly beaten back. A delegation representing a number of northern Campanian cities led by prosperous Capua pleaded for military protection on the floor of the Roman Senate. After brief deliberations, the Romans reneged on their treaty with the Samnites and determined to go to war to protect their Campanian interests.

The precise reasons why the Romans broke their prior treaty remain unclear. Perhaps it was the great wealth of the Campanian cities, the characteristic Roman desire for further expansion, or the realization that a turf war with the Samnites was becoming inevitable and might as well come now as later. At any rate, when the Romans sent their armies into the field, the Samnites showed no misgivings about fighting their former allies. The First Samnite War was brief. In the opening year the Romans scored a major victory, but for most of the next year civil unrest and mutiny within their army pulled attention away from the conflict. At the same, the Samnites had their own problems, being forced into a border war in southern Samnium. Before any further action could begin in 341, the Samnites initiated negotiations with Rome, and the two sides settled their grievances—for the time being.

The peace of 341 essentially restored prior treaty obligations, infuriating the northern Campanians, as well as the Sidicini. These two groups joined forces with a growing rebellion inside Latin cities that were looking for an opportunity to curb Rome’s increasing power. Emboldened by a belief that Roman attentions were focused elsewhere, the coalition sent armies into the field, but in just three years the Romans reduced the Latin rebels and broke up their coalition. Rome made treaties with each individual Latin city, as well as with the northern Campanian cities. These two newly dependent groups would give Rome a significant advantage in the next war with the Samnites, which the Romans already were anticipating. They doubted the Samnites would honor the existing treaty.

Lessons of the Conflict

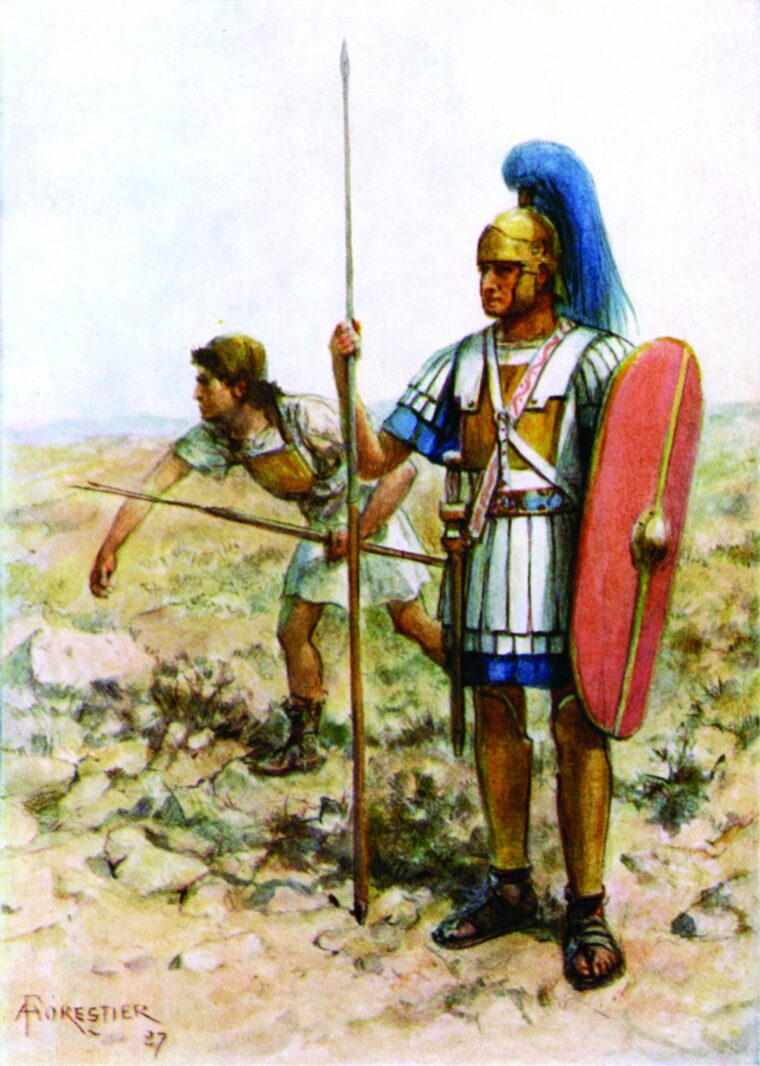

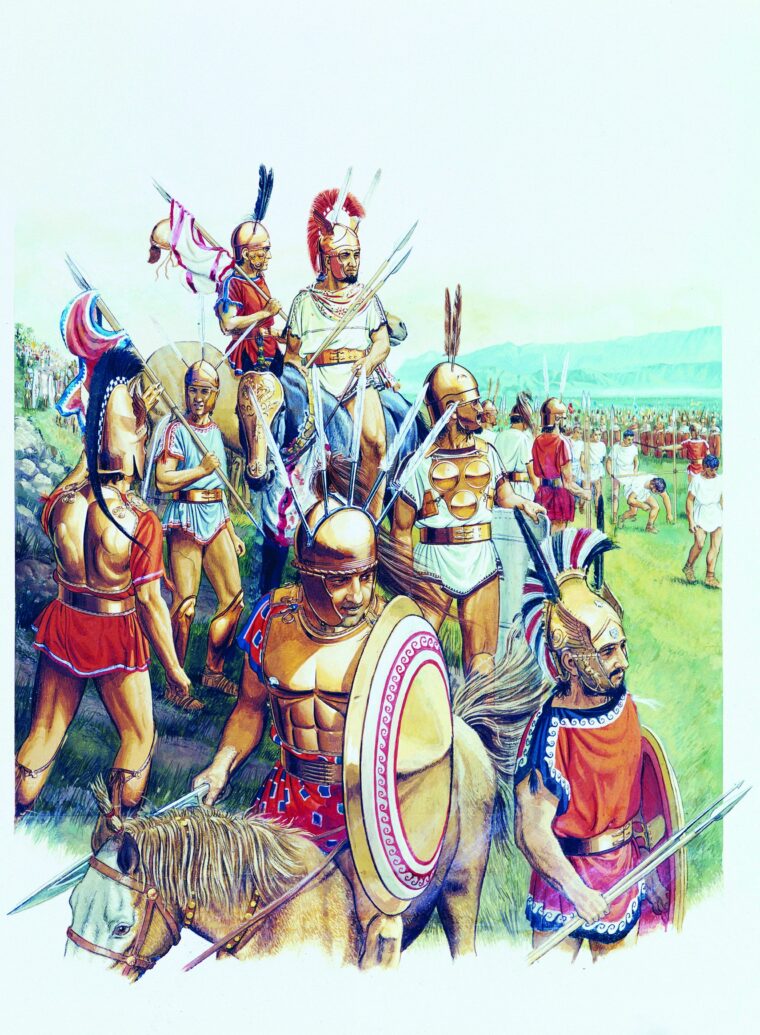

The first Roman-Samnite conflict had revealed much about the military systems of the two states. The Romans were still fighting in a Greek-style phalanx, with densely packed soldiers in a rigid formation equipped with long spears and heavy body shields. This old-style formation required an open and level plain upon which to operate effectively, and it was particularly ill-suited to fighting in the rugged terrain of the central Apennine region. There the Romans first made contact with the lightly armed and highly mobile Samnite warriors. The loose-order Samnite tactical formations and weaponry—which included throwing spears and other missile weapons—gave the Samnites an advantage in such an environment.

The Romans, never afraid to implement new measures, even those learned from an enemy, observed the benefits of mobility under such circumstances, and they introduced the revolutionary manipular legion. This new tactical formation classified Roman infantrymen into three lines—the youngest frontline men were the hastati; they were followed by the older and more experienced principes and the seasoned veteran triarii safeguarding the rear. The first two lines were similarly equipped, with each man wearing helmet and body armor and carrying a longer-pattern shield. The panoply was rounded out with javelins and short thrusting swords. The triarii carried different arms, including a long spear like a phalangist’s pike, which suited their function of administering the coup de grace to shaken enemy ranks. The three-lined formation (triplex acies) allowed for greater mobility and a flexible system of cycling reserves to the front. In addition to the infantry, poorer citizens called velites formed a skirmishing line, while wealthier Romans and allied contingents formed a highly competent cavalry.

Even with this new organization, the Roman legionary remained a part-time citizen soldier, drafted usually for one year of military service. From year to year a specific legion might be filled with a different selection of soldiers, a practice that did not cultivate the esprit de corps and unit pride of later generations. Despite the training and strict discipline of soldiers during their tour, Roman armies were still amateurs. The politicians who commanded the legions were little better prepared for combat than their men. Military commands in the Republic were originally delegated to the two annually elected chief magistrates, or consuls. During a period when multiple fronts had to be covered, a special commander called a praetor could be appointed to conduct a campaign. The Republican system of government also possessed the ability to extend the term of a magistrate, while the consuls had the power to nominate a temporary dictator. These extraordinary military commands became quite useful during the Second Samnite War.

When the Romans used military action to capture a city, their conduct entailed some of the basic tactical elements of a siege. However, the Romans had little knowledge of the advances in the science of siege craft in the post-Alexandrine Greek world. They had no siege engines, towers, or battering rams, and made little use of missile troops so valuable in siege operations. To capture a fortified city, Roman commanders had to rely on storming the ramparts before the defenders could mount an effective resistance. Otherwise, Roman armies could only surround a city and hope to starve out the defenders, or carry a city by deception with the aid of a fifth-column faction operating within.

Fortifying the Border with the Samnites

In 334, the Senate sent a three-man commission—triumviri coloniae deducendae—to oversee the settlement of 2,500 Romans at Cales on the Campanian-Samnite border. This colony added security to Rome’s interests in northern Campania and provided a point of entrance into Samnium whenever hostilities erupted again. Cales also allowed the Romans to operate in the important border lands of the Sidicini, which were once again threatened by Samnite incursions. In the same year, the Senate extended partial Roman citizenship to many northern Campanian cities. The status granted to the Campanians was civitas sine suffragio—a city without voting rights in Rome. They were allowed to maintain local autonomy but owed allegiance and certain obligations to Rome, most notably to make their troops available whenever the Senate called.

For the remainder of the decade, the Romans fought against and subdued the Volscians of central Latium, turning two of their towns into dependents. The Senate also made a treaty with Alexander of Epirus, a Greek mercenary general who was operating against Samnite interests in the southern regions of Apulia and Lucania. Partial citizenship status was granted to the people of Acerrae, whose city lay in central Campania. These gains provided Rome with new points of access into western Samnium and expanded Roman control in southern Latium. This was merely the beginning of an ever-entangling Roman web of isolation that placed a powerful stranglehold on the Samnites who were outside its fraternal embrace.

The Roman consuls for the year 329—Lucius Aemilius Mamercinus and Gaius Plautius—entered office in July, the beginning of the Roman political year. The Senate dispatched them to south-central Latium to deal with the rebellious city of Privernum. The city had spread anti-Roman sentiment to nearby Fundi; the latter quickly fell in line once the consuls approached, offering hostages to emphasize their loyalty. The consuls then encircled Privernum, capturing it in just a few weeks. The man responsible for the uprising was Vitruvius Vaccus, a wealthy noble who kept a house in Rome. He and the other ringleaders of the plot were taken back to Rome and executed during the consuls’ triumphal parade through the streets. After razing the walls of Privernum and installing a Roman garrison, the Senate offered citizenship to the remaining Privernates. This measure did much to secure the loyalty of Privernum and outlying areas. To follow up their military success in the region, the Romans sent 300 colonists to Anxur, just south of Privernum. The three cities secured during the year created a strong base of Roman control along the Latin-Samnite border. In 328, this base was strengthened even more by the establishment of a Roman colony at Fregellae, an important and much disputed town in Volscian territory.

The Second Samnite War

During the year 327, the Romans did not extend their territorial gains directly. Instead, they sent the first troops into the event that sparked the outbreak of the Second Samnite War. Palaepolis, an important city on the western coast of Campania, began threatening Roman-allied Capua. As wealthy Capua was the capital of Campania, its protection was paramount to Roman power in the region. The situation at Palaepolis gave the Romans the opportunity to frame the emerging conflict as a defensive war. The Palaepolitans, emboldened by either a report of plague in Rome or Samnite encouragement, soon began raiding other Roman interests in northern Campania. The situation escalated rapidly after the Roman consuls sent to diffuse the matter were promptly dismissed. The Senate pressed for war, and in the comitia centuriata, where such matters were resolved, the decision was made to send an army against Palaepolis for the purpose of defending Capua and Roman control in northern Campania.

The consuls received their orders and marched immediately, Quintus Publilius Philo to Palaepolis and Lucius Cornelius Lentulus to the northern Campanian border to meet an anticipated Samnite counterstrike. Publilius reported that 2,000 soldiers from Nola had united with 4,000 Samnite warriors and gained entrance into Palaepolis. Lentulus sent word that levies were being called up all over Samnium, and that their armies would soon be on the move. The eleventh-hour diplomacy between the Romans and Samnites was quick and unsuccessful. As might be expected from negotiations between two armed and motivated camps, accusations and warnings were tossed about, ending with a Samnite delegation storming out of the Senate with one of its members remarking prophetically, “Let us settle the question whether Samnite or Roman is to govern Italy.” As tensions at Palaepolis increased into full-scale war, both sides relished the coming conflict, confident of their prospects for victory.

Two New Fronts Against the Samnites

In 326, cities in Apulia and Lucania sent word that they wished an alliance with Rome, as they too were enemies of the Samnites. The Romans had no connection or influence in these regions prior to the entreaties, but they quickly realized the benefits that could be exploited from control in southern Italy. This new alliance opened two new fronts for the Samnites to defend and gave the Romans access to southern Samnium. Roman consular armies also made inroads into western Samnium for the first time, capturing Allifae, Callifae, and Rufrium, while ravaging crops and farmland as they campaigned in the region, a standard tactic of ancient Mediterranean warfare. In 326, Palaepolis finally fell to the Romans, under the direction of the prorogued consul Publilius. For this operation, Publilius earned a distinctive honor—he became the first Roman commander to celebrate a triumph for a victory attained after his official term had expired.

During the next four years the Romans continued to solidify their position on multiple fronts. In 325, the Vestini, whose land lay on the eastern coast of Italy just beyond the northern border of Samnium, concluded an alliance with the Samnites. In response the Senate sent the consul Junius Brutus Scaeva to combat this new threat. Scaeva conducted a brutal campaign against the Vestini, pillaging and murdering along the way to capturing Cutina and Cingilia. In addition, Roman forces continued to advance into Apulia. In 324 and 323, the dictator Lucius Papirius Cursor and his associate won a pair of stunning victories in the field. By some accounts, the Samnites suffered 20,000 casualties during the campaign. The Samnites, although worn down, were by no means defeated; the Romans did not fully appreciate this fact. Seeking a respite to rally their forces, the Samnites sent a peace-seeking mission to Rome with a proposal to restore the terms of the 341 treaty. In a haughty mood, the Romans suggested instead that the Samnites recognize their hegemony over all of Italy.

Bloody Blunder at the Caudine Forks

By the time the Samnite delegation approached Rome about a truce, the Romans had already established a strong influence in the upper Liris valley, as well as control of the Campanian seaboard and a secure foothold along Samnium’s northern border. Moreover, Roman influence was gaining momentum in Apulia. Their position was quite solid, and they must have felt that the Samnites were on the verge of defeat. In its arrogance and desire for a quick battlefield victory, the Senate explicitly rejected the Samnite peace proposal. In doing so, the Romans deviated from their previously patient strategic plan. This lapse led the new consuls, Spurious Postumius and Titus Veturius Calvinus, to step blindly into disaster at the soon-to-be-infamous Caudine Forks in 321.

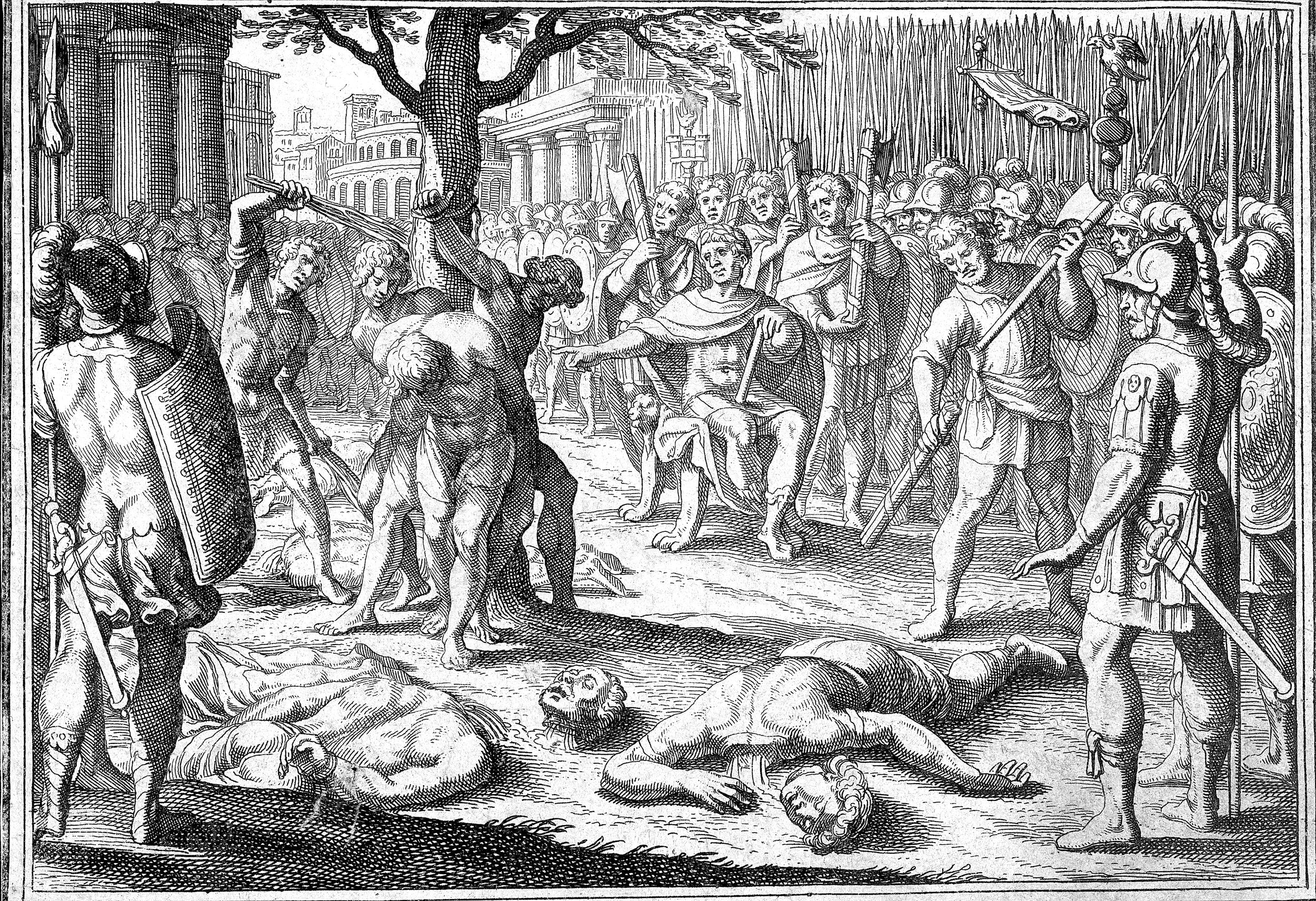

In one of the worst military blunders in Republican Roman history, a Roman army of 20,000 men nearly came to ruin in the Apennine mountain pass known as Caudine Forks. Samnite general Gaius Pontius had set an ambush at the difficult passage and drawn in the imperious Roman consuls through misinformation. After being trapped for a number of days with no means of escape, the consuls were compelled to accept a treaty dictated by Pontius. The terms called for the return of all captured Samnite territory, the surrender of all Roman forts and garrisons, and a promise to end the war; Pontius kept 600 Roman knights captive as insurance. He then stripped the remaining Roman soldiers and forced them to march out of the valley under the Samnite yoke, through the gamut of jeers and taunts from the assembled Samnite warriors. This defeat brought howls of anger back in Rome, but the citizens soon recognized their good fortune in the bloodless resolution of the siege. When the dust had settled, the Senate repudiated the Caudine treaty as an unauthorized action by the consuls, and it even sent the guilty magistrates back to Samnium. The following year, two experienced soldiers were elected consuls, and the Romans hoped to get back on track after their rare defeat.

A Lull Under the Caudine Peace

The Romans had barely missed having an entire army slaughtered at Caudine Forks, a setback that could have been devastating to their cause. But the Caudine settlement did not halt Roman plans for long, and they renewed their commitment to the effective strategy of isolating the Samnites. In 319, Lucius Papirius Cursor, now consul and rapidly emerging as one of the most skilled generals of the period, secured the major northern Apulian city of Luceria. The consul relished the victory, particularly when he ordered the 7,000 Samnite defenders to march out under a Roman yoke. Luceria was the key to all of northern Apulia, offering the Romans a prime strategic base of operations in the region. What was more, the city was not far from the Samnite border itself. The consuls then united in southern Latium to restore Roman control of Satricum and Ferentinum, two Latin cities that had revolted after the Caudine disaster. Roman armies also began operating in Umbria at this time.

In 318, Roman armies expanded their power in Apulia by taking control of Teanum on the northern Apulian border and Canusium, the major city on the Aufidus River. The next year the Senate assigned a Roman prefect to Capua to assert Rome’s control in the important central Campanian city. Also in 317, the Romans extended their southern campaigns into Lucania, an area that long had been susceptible to Samnite influence. Consul Gaius Junius Bubulcus took control of Forentum, just inside the Lucanian-Samnite border. The web of isolation being woven by Rome was tightening on the Samnites. Roman control in Campania was stronger than ever, while the legions were gaining along Samnium’s northern border. There were few Samnite operations on the Samnite-Apulian border, and the Romans were able to cover the entire area from a network of their three major bases at Luceria, Canusium, and Teanum. As satellites for their Apulian bases, the Romans also captured and maintained outposts inside southern Samnite territory. It was during his account of these operations that the Roman historian Livy observed, “Not Roman arms alone but also Roman law began to exert a widespread influence.” The method of using military action and diplomacy in tandem was paying off.

Escalating the War

Despite continued operations by both the Romans and Samnites during the lull in the war, it took an attack by an emboldened Roman dictator to formally break the Caudine peace. The initial attack on the border Samnite city of Saticula came in 316. Following a year-long siege, the Romans sacked the city. In 314, the Romans captured Sora in southern Latium and conquered the territory of the Ausones along the upper Liris. In this same year, the Senate received reports that Roman influence in Campania again was being compromised by a growing faction. A dictator was appointed, and he quickly exposed the plot and dealt with the conspirators. The Senate also sent 2,500 Romans to colonize Luceria, further extending their control of Apulia.

The year 313 was a busy one for Roman armies, as the consuls were accompanied in the field by two different dictators and their lieutenants. Fregellae, having since fallen back into Samnite hands, was recaptured, along with Nola, Atina, and Calatia. Control of the latter three cities had important strategic implications on the western border of Samnium. This year also saw plentiful Roman colonization. A three-man commission led colonists to Saticula, while 4,000 Romans settled in Interamna on the Liris. At Suessa, in the territory of the Sidicini, another contingent of Romans established a colony. In addition, the Romans began planning for naval operations, founding a colony on Pontia, an island off the west coast of Latium. By 312, the Samnites were on the verge of capitulation; their federation was beginning to crack. The Roman plan of isolation was putting pressure on the Samnites from all sides, and their new bases allowed for expedient seasonal raids and attacks on the increasingly embattled enemy.

A rumor began circulating that a new coalition of Etruscan cities was forming on Latium’s northern border. The Senate appointed a dictator and a master of horse to deal with the potential threat, a show of force that prompted the Etruscans to turn back. That same year, Appius Claudius began his term as censor, a position that entailed a wide range of civic responsibilities, and he launched an ambitious public works program. The most important strategic element was the paving of the Via Appia, a smooth and solid road running from Rome to Capua. This was an immensely expensive undertaking, but it was a key to the continued security of Rome’s power in Campania. The road provided for the rapid transit of Roman troops along the Campanian seaboard, and it enhanced the communication between Rome and its southern territories. Adding to the defensive aspects of the project, points along the road served as useful depots for attacks into the Samnite heartland. The Romans also reasserted their influence in Sora, on the fringe of southeastern Latium, and began advancing against the Marrucini, whose lands straddled the northern edge of Samnium.

During 311 and 310, the Samnite federation continued to crumble as the Romans pressed their advantage. Consul Gaius Junius Bubulcus reestablished a Roman garrison at Cluviae in Samnium, then besieged Bovianum in the heart of Pentrian Samnite country. After a short period of ineffectual siege operations, the consul withdrew, but the capture of the wealthiest city in Samnium remained a primary Roman objective. Roman armies established new outposts in Apulia, while reopening campaigns in southern Umbria and Etruria. Lucius Papirius Cursor, serving a term as dictator, followed up these campaigns with the capture of Longulae in Samnium.

Military Reforms and Battlefield Successes

In 311, the Roman military underwent organizational changes meant to strengthen the armies as they fought on multiple fronts. The military tribunate was expanded, giving the popular assemblies the right to elect four tribunes for each of Rome’s four legions. This measure made it easier for the Romans to retain the services of their most experienced commanders, men with an expertise in the strategy of isolating the Samnites. In addition, new levies from Campania were likely formally organized and incorporated into the new Roman military structure. In 310, there were created for the first time two naval commissioners to supervise the construction and operation of Rome’s first fleet. In that same year, the Romans regained Allifae in west-central Samnium, dealing a serious blow to the resolve of the Pentrian Samnites. Despite Roman victories in the field, the Samnites remained strong in manpower. In one battle in 309 they deployed a newly outfitted army, but a combined Roman and Campanian force routed them. In 308, Nuceria Alfaterna was captured. This coastal city was the farthest south that Roman power had yet extended, allowing them the opportunity to link up their garrisons in Lucania and to complete a net across southern Samnium with a connection to Roman control in Apulia.

During the next few years, the Romans maintained their hold on the Samnites, who did little to break through the Roman ring of isolation. Simultaneously, the Romans conquered much of southern Latium by both sword and citizenship, taking control of the important border areas of Arpinum and Auruncia, among other gains. In 305, the Romans renewed their campaigns into the heartland of Samnium, and the combined consular armies finally completed the long-awaited capture of Bovianum. The surrender of this stronghold devastated Samnite military capacity.

Ending the Second Samnite War

Exhausted after enduring 20 bloody years of war, the Samnites could not break the Roman stranglehold that had progressively tightened. Nor were they able to put a viable defensive effort into the field. A delegation representing the remaining Samnite federation traveled to Rome to seek peace terms. Even now the Senate suspected treachery—perhaps the Samnites once again only desired a reprieve to rally their forces. Instead of considering the peace proposal, the Senate dispatched the consul Publius Sempronius to Samnium. Sempronius marched the length of the region and found that the formerly hostile towns were quite accommodating to his army. At his assurance that the Samnites were sincere, the Senate reconsidered the proposal and agreed to peace in early autumn 304.

The settlement did not reduce Samnite territory substantially, while the terms of the 354 Roman-Samnite treaty were largely restored. The Samnites had to abandon their claims in the Liris valley and other gains made during the 20-year war, but they retained control of their homeland as firmly as ever. Perhaps the most important aspect of the 304 treaty was the universal recognition of Rome’s many conquests during the conflict. To further drive home this point, the Romans also reduced and concluded treaties with the Marsi, Paeligni, and Marrucini, tribal groups positioned along the northern Samnite border. During the final years of the fourth century bc, the Romans strengthened the buffer zone between their lands and the Samnites on other fronts. Never again could the Samnites alone seriously threaten Roman supremacy in Italy.

Roman Mastery of Italy

The victory taught the Romans a number of important lessons. At the outset of the conflict, the military capabilities of the Romans and Samnites were nearly equal. Victory in the war pivoted on the Roman inclination for strategic thinking, as they employed military action in combination with diplomacy to surround the Samnite homeland. While the Romans maintained their web of isolation, the Samnites could not break the stranglehold, and they were overcome. The Roman policy in the war was certainly quite successful. The Fasti Triumphales Capitolini—inscriptions celebrating significant military victories during the Republic—record no less than 11 triumphs during the years of the Second Samnite War.

In a third conflict with the Romans, the Samnites formed an imposing coalition with other groups in central Italy that also wanted to halt Rome’s expansion. But Rome’s strategic alliances and assets throughout Italy proved decisive. When the last stand of native resistance was crushed by the legions in 295, the Romans took a step closer to the mastery of Italy. The Second Samnite War had enabled the Romans to put into practice advanced strategic planning and implementation on wide scale. Such skills would serve the Romans well as they expanded their empire in centuries to come.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments