By Blaine Taylor

When British diplomat Lord Halifax arrived at the Berghof in the Bavarian Alps on November 19, 1937, he mistook German Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler for a footman and was about to hand him his coat and hat when Foreign Minister Baron Constantin von Neurath hissed, “The Führer! The Führer!”

Hitler’s Views on India

Following a dismal luncheon, Hitler told his guest that his favorite film was Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and that the movie was compulsory viewing for his SS because “this was how a superior race must behave.”

Then he launched into a tirade for the benefit of the former British Viceroy of India about what to do in response to Great Britain’s current problems in that unhappy land: “Shoot Gandhi! If that does not suffice to reduce them to submission, shoot a dozen leading members of Congress, and if that does not suffice, shoot 200 and so on until order is established,” said Hitler.

That night, Lord Halifax, called the “Holy Fox” by his peers, confided to his diary, “He struck me as very sincere, and as believing everything that he said…. We had a different set of values and were speaking a different language.”

Earlier, in his infamous book Mein Kampf, Hitler turned his attention to the subject of British India. “I still remember the hopes, childish as they were incomprehensible … to the effect that British power was on the verge of collapse in India.

“Some Asiatic jugglers … real ‘fighters for Indian freedom’ … had … [been] expecting the end of the British Empire to follow from a collapse of British rule in India. If anyone imagines that England would let India go without staking her last drop of blood, it is only a sorry sign of absolute failure to learn from the World War … and ignorance on the score of Anglo-Saxon determination….

“England will lose India either if her own administrative … machinery falls a prey to racial decomposition … or if she is bested by the sword of a powerful enemy. Indian agitators, however, will never achieve this … I, as man of Germanic blood, would … rather see India under English rule than under any other.”

So Hitler concluded in 1925, but he was proven dead wrong on August 15, 1947, when, in fact, Great Britain did grant independence to such “Indian agitators” as Mohandas K. Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Subhas Chandra Bose, the last name being virtually unknown in the world outside India to this day.

Subhas Chandra Bose: “Darling of the Axis”

Known to his many followers as the Netaji (Respected Leader) of the Azad Hind (Free India) movement, Bose was called “the darling of the Axis” by his biographer Marshall J. Getz in Subhas Chandra Bose (2004) and termed a “charlatan” by German postwar chronicler Max Domarus in Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations, 1932-45.

Having met with Hitler, Italian Fascist Duce Benito Mussolini, and Japanese Premier General Hideki Tojo, Bose was, at one time or another, backed by all three of the major Axis powers. By 1943, he also held a trio of titles.

Bose was born in Calcutta on January 23, 1897, the son of a lawyer, and came from a family of 26 generations of soldiers, writers, and poets. Having studied both yoga and transcendental meditation, Bose entered college at age 16 in 1913. Thus, he was reared and educated in the traditions of the Raj that had grown out of the British Crown Colony claimed by the East India Company in 1757 during the first year of the Seven Years’ War. Indeed, as a student, Bose even wrote an essay praising George V, the British king.

A liberal Hindu from a Muslim area, Bose fought the Raj as a socialist. He later tilted toward European fascism and established and then led military forces for the creation of Greater India in three theaters of war under the Springing Tiger flag made up of members of the Indian communities of Malaya, Burma, Singapore, and Thailand.

Deeply interested in the history of his country, Bose as a student was greatly influenced by the Swadeshi (Our Country) and Swaraj (self-government) movements. Indian nationalists had felt sympathy for the Kaiser’s Germany during World War I; thus, Bose later saw Hitler as a fellow revolutionary against Great Britain.

By 1941, Bose had helped create the Indian Liberation Army (ILA) and joined the fascists in what he thought was the most direct path to Indian independence and home rule. He had headed the All-India Trade Union Congress in 1929, and the Raj later branded Bose a terrorist and had him jailed.

Elected mayor of Calcutta in 1930, Bose published his book, The Indian Struggle, six years later. During the years 1933-1936, he traveled to Warsaw, Prague, London, and Dublin. He was hailed in Dublin as a kindred rebel. Bose also appeared on the cover of Time magazine. While abroad, Bose studied the revolutions of Italy, Ireland, Turkey, and Russia. His turn toward fascism came as a result of Soviet attempts to dominate China and also the Soviet abandonment of the domestic Indian Communist Party.

A Rival to Gandhi, a Pawn to the Axis

A rising figure, Bose was considered “the black sheep of Indian politics” and wanted a national leftist government before his break with Nehru in April 1939. Bose founded the Forward Bloc that rivaled Gandhi’s own Seva Sangha Party, and in April 1940 he called for riots and strikes against the British.

Despite his open support of a fascist victory in World War II, as early as March 1936 Bose was shocked to discover that Indians in Berlin were regarded as “colored” people and that when he was in Germany he himself was routinely followed by the Nazi Gestapo (Secret State Police.) His biggest supporter in the Third Reich was Nazi Propaganda Minister Dr. Josef Goebbels.

Bose gave an anti-British speech in Calcutta on June 31, 1940, and was arrested and sent to prison for the 11th time. There he came to a trio of conclusions: the Axis would defeat the Allies, the United Kingdom would retain India and, in return for Indian aid to the Axis, the Axis would set India free. Was he naïve? Possibly, as it is difficult to imagine Hitler, Mussolini, or Tojo freeing India once it had been conquered militarily.

Following a hunger strike and threats of suicide, Bose was released by the British and then disappeared from public view before turning up at the German Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan, where his initial political advances were rebuffed. His later negotiations at the Italian embassy led to a tentative agreement by Italy, Germany, the Soviet Union, and Afghanistan to back Bose, who wanted both Il Duce and the Führer to sponsor an expeditionary force to invade India as a catalyst to spark a full-scale revolt against the British.

The Meetings Between Hitler and “the Indian Charlatan”

In March 1941, Bose reached Berlin via Moscow and offered the Nazis an outright military alliance against the United Kingdom. Far from fearing a German military invasion of India that both Hitler and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel were planning, Bose wanted to include the Imperial Japanese Army as well.

For their part, the British were wary of a joint German-Soviet invasion of both Afghanistan and the Indian subcontinent. Meanwhile, the Afrika Korps was capturing thousands of Indian prisoners of war who had been fighting for Britain during 1941-1942, from which Bose envisioned the future ILA that would free their country from the hated British yoke.

They would end World War II as members of Reichsfuhrer Heinrich Himmler’s Waffen (Armed) SS, a supreme irony for the “turban-wearing, brown-skinned men” in the ultra-racist Nazi Germany, according to author Christopher Ailsby’s book, Hitler’s Renegades: Foreign Nationals in the Service of the Third Reich.

Bose set up the Free India Center in Berlin and began radio broadcasts from Nauen, Germany, to his far-off homeland on February 19, 1942.

Bose’s British Broadcasting Corporation rival and counterpart, author Eric Blair (aka George Orwell of Animal Farm and 1984 fame), led the Allied propaganda team that fought Bose over the radio. On March 1, 1942, Free India declared war on the United Kingdom.

On May 4, Bose met with Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano in Rome and Il Duce himself on May 5, but still Berlin vetoed overall Axis support for his movement even after Mussolini fully committed Fascist Italy.

On May 29, 1942, Bose met the Führer at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. According to Getz, “The Führer … asked Bose what his plans would be if the Axis refused to help him. Misunderstanding slightly, Bose told his interpreter to ‘please tell His Excellency that I have been in politics all my life and that I do not need advice from anyone.’”

A second and final meeting between Hitler and “the Indian charlatan” took place the following July 15 at Wolf’s Lair, Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg, East Prussia.

The ILA: “Cowardly, Rebellious, and Barbaric”

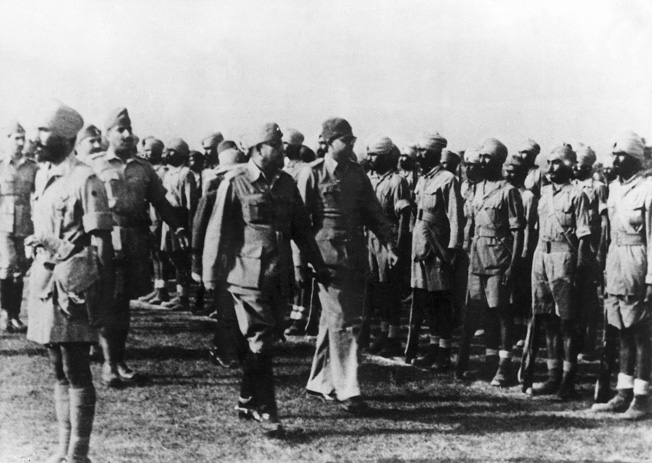

Meanwhile, the men of the newly formed ILA refused to serve under Italian officers because of their own colonial record in North Africa, and thus it was that the Nazis recruited and trained 27 officers and 10,000 enlisted men at Annaberg in Saxony; the troops comprised Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu components, each man wearing the symbol of a springing tiger on the tricolor shield of India on his uniform sleeve.

Ironically, these former British Imperial Army men took the oath of allegiance on August 26, 1942, to Hitler, Bose, and India—in that order—as Brandenburg Commandos. They were later incorporated into the German Army as the 950th Infantry Regiment with 2,593 men in three battalions. Most wore tropical-style uniforms with peaked forage cap with the standard Nazi eagle and swastika on their breasts. Their helmets featured both the Indian and German national colors.

The man who originally captured them, Rommel, refused their usage in combat on his side “for being cowardly, rebellious and barbaric.” Indeed, the Germans never did commit this new Indian National Army (INA) to combat, and with good reason. There were instances of reported mutinies. At this point, it looked as if Bose’s lifelong goal of Indian independence was as far off as ever.

It was the Japanese who came to his political rescue in February 1943. The armies of Imperial Japan, the so-called Floating Kingdom, had been welcomed with open arms by the scattered Indian population enclaves throughout Southeast Asia during their march of conquest early in 1942.

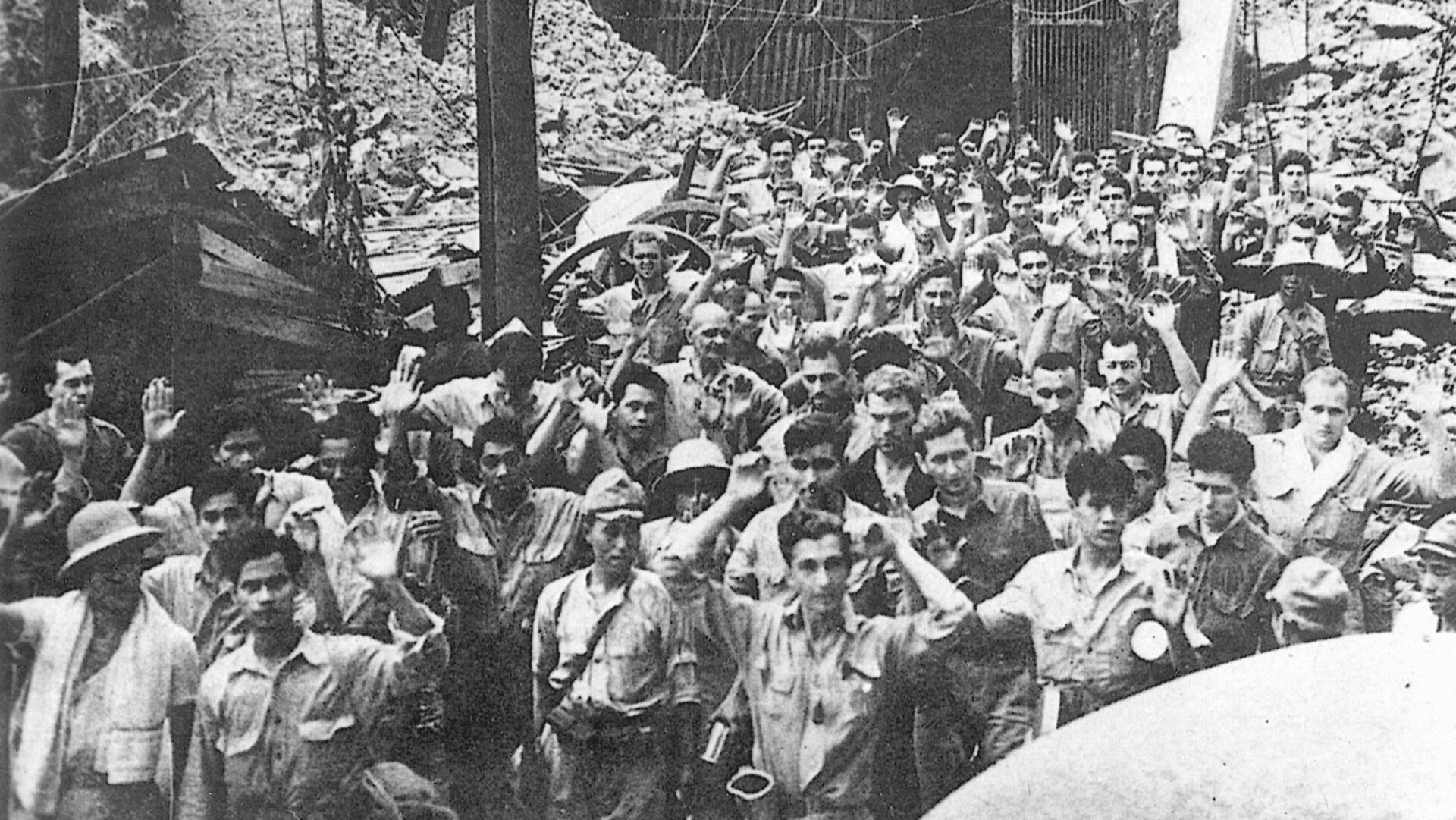

Just as in North Africa earlier, on February 19 fully 45,000 Indian soldiers of the British Army surrendered to the Japanese and were pressed into service with the Japanese version of the Indian National Army. Its initial commander, Mohan Singh, was fired by the Japanese, however, and his force dissolved on December 29.

Creating the Indian National Army: “On to Delhi!”

For his part, having had little luck with the German and Italian fascists, Subhas Chandra Bose was smuggled out of the Third Reich in a German U-boat bound for the Far East. In Tokyo, Bose shook hands with General Tojo and got yet another lease on political life.

Nominal leader of the new Japanese Indian National Army that had a Nipponese field marshal as chief of staff, Bose hailed Imperial Japan as the liberator of both Asia and India. In July 1943, he took over the Indian Independence League and the INA in Singapore, and at the subsequent military review compared his new force to the legions of George Washington and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Their goal was at once both simple and bold: to take the Red Fortress of Delhi, British military headquarters for the Indian Raj.

This time, however, Bose and his men swore allegiance to Free India, not the Axis, with the headquarters of the new provincial government of Free India based in Singapore. Bose also rejected both the exclusionary caste and religious aspects of the Royal Indian Army of the British Raj in favor of the triad themes of “Unity, Faith, and Sacrifice.”

Bose was formally declared president of Azad Hind (Free India) on October 21, 1943. His core belief was that World War II gave India the chance to liberate itself. Like Il Duce and the Führer before him, Bose now claimed the multiple titles and offices of head of state, prime minister, minister of war, and head of the foreign office. On the 23rd, the new chief executive officer made a state visit to Japan’s Emperor Hirohito during the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo, while Premier Tojo ceded the islands of Andaman and Nicobar to Bose’s new regime. On November 18, 1943, Chief of State Bose traveled to Nanking, China, as well.

By then, the INA numbered 12,000 men charged with the battle cry of “On to Delhi!” In March 1944, the force invaded India and battled West African soldiers on the Burmese Arakan Front, with Azad Hind being a reality in the Indian border states of Mizoram and Manipur.

Asserts Getz, “Bose had grown into a serious threat: a Bose-Nehru-Gandhi-Japanese alliance that the British Raj feared above all. Although both Gandhi and Nehru were anti-fascist, they still advocated a tacit alliance with the Japanese nonetheless, but rejected joining either the INA or the IJA. Both the British and Bose now felt that the Raj would fall to the Japanese.”

Bose advocated burning the Raj to the ground, while top American magazines gave him prominent coverage and Allied intelligence overestimated his forces.

Defeat at Imphal and the Collapse of the INA

The high-water mark of his epoch was the Battle of Imphal on July 20, 1944, but the Japanese Army retreated, abandoning the INA to a British counterattack, two million strong. By the fall of 1944, the INA was in complete rout.

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany on May 7, 1945, Bose considered tilting toward fellow “socialist” Generalissimo Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union, but nothing came of it in the end. For its part, the Communist Party of India (CPI) labeled Bose “the running dog of Japanese fascism.” The Provisional Government of India (PGI) had been disbanded when the Allies retook Burma.

The future of this “would-be Führer” and “Indian Quisling,” as he was called, now looked dark, indeed, even as he continued to chant “Jai Hind!” (Free India!). Before their surrender, Bose asked the Japanese to send him to either Shanghai or North China.

On August 17, 1945, Subhas Chandra Bose flew out of the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon aboard a Japanese bomber heading north for either Manchuria or the Soviet Union. Following takeoff from a refueling stop on Taiwan, an engine blew up and the plane crashed in flames.

About seven hours later, Bose died from burns in a Taipei hospital. Owing to his 1941 escape from the British in India, many people refused to believe that Bose was, in fact, dead, and it was not until 1956 that The New York Times finally published an obituary that was by then 11 years old.

Of Bose’s troops, Hitler asserted near the end of the war, “If one were to use the Indians to turn prayer wheels, they would be the most indefatigable soldiers in the world … The Indian Legion is a joke! There are Indians who can’t kill a louse, and would prefer to allow themselves to be devoured. They certainly aren’t going to kill any Englishmen … It would be ridiculous to commit them to a real blood struggle.”

While he may have been right about the INA, it is a military fact that Indian troops fought well against both the Germans in North Africa during 1941-1943, and then, later, against the Axis forces in Italy during 1943-1945.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments