By Al Hemingway

Private First Class Frank Rinaldi cautiously made his way through the dense foliage. He and other soldiers were on patrol when they heard the unmistakable sound of Japanese voices, and they inched their way forward to investigate. To their surprise, they had stumbled upon a group of enemy combatants performing close-order drill. Rinaldi and the others had been in the jungles of Burma for months and had become experts in jungle fighting, and soon learned how to sneak up on the enemy without being detected. They were members of an elite unit referred to as Merrill’s Marauders.

As the patrol moved closer, the machine gunner, a Chicago native named Farino, held up his hand and whispered, “They’re mine.” Suddenly, the air erupted with the crack of .30-caliber rounds ripping into the Japanese. “After it was over,” Rinaldi later said, “we counted 80 bodies.”

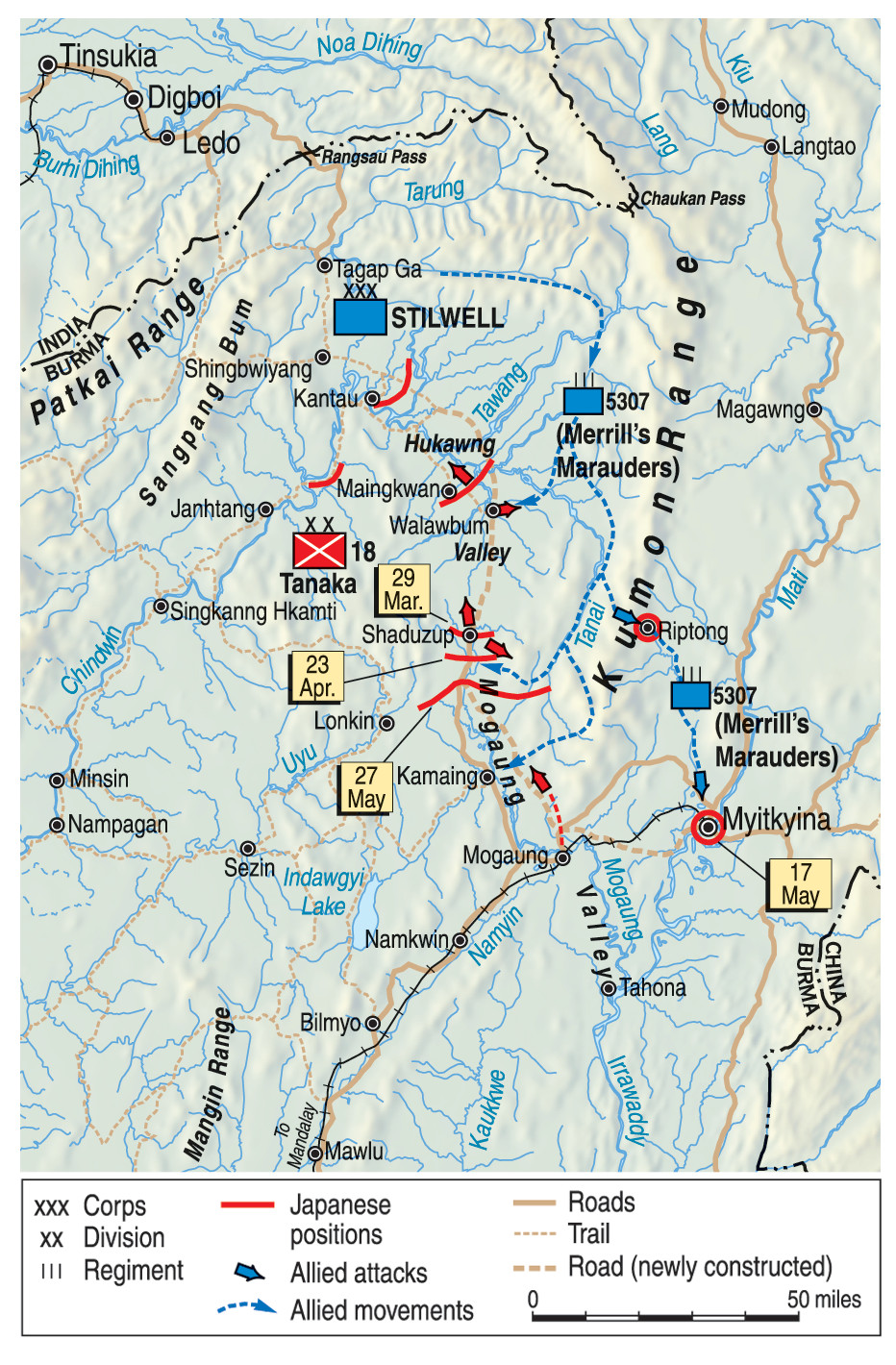

Since the outbreak of World War II, the Japanese had moved rapidly and seized most of Burma. Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, CBI (China-Burma-India) commander, remarked, “I claim we got a hell-of-a-beating. We got run out of Burma, and it was humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back, and retake it.”

The eccentric British Major General Orde C. Wingate had organized and trained a group of jungle fighters in 1942 to take the war to the Japanese deep within the Burmese jungles. The unit was officially named the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, but everyone knew it by its nickname, the Chindits, a mythical beast, half-eagle and half-lion, that guarded the Buddhist temples throughout the country.

Wingate’s Chindits participated in a raid, dubbed Operation Longcloth, in February 1943 that really did not accomplish anything militarily. It did, however, excite the public back in Britain, which was starving for any positive news from the CBI Theater. Because of this, the Chindits’ popularity rose, and they took part in Operation Thursday in early 1944.

Merrill’s Marauders

Captivated by the aura that surrounded the Chindits, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered that an American unit, similar to Wingate’s Chindits, be formed to fight in the CBI Theater. It would be the first and only U.S. ground force in World War II to fight on the Asian mainland.

Volunteers came from various Army units for a “dangerous and hazardous mission.” Approximately 3,000 soldiers answered FDR’s call, and they created the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), codenamed Galahad. The men were split up into six combat teams: Red, White, Blue, Green, Orange, and Khaki; two teams were in a battalion with the remainder of the soldiers forming headquarters company and air transport units.

This was an odd name for a combat unit, but soon Life magazine reporter James Shepley dubbed the group “Merrill’s Marauders,” after the outfit’s leader, Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill.

Merrill, sporting his wire-rimmed glasses and clenching a pipe between his teeth, resembled a college professor rather than a combat leader. Merrill, however, had garnered an impressive record since graduating from the United States Military Academy in 1929. He received an engineering degree from MIT and was assistant military attaché in Tokyo in 1938, where he studied Japanese and Chinese. Since the start of the war, Merrill had been enjoying a meteoric rise from major to major general in a short span of time and he was assigned to lead the newly organized unit that would bear his name.

After a long and arduous ocean voyage, the unit disembarked in Bombay, India, and began jungle warfare training under the auspices of Brig. Gen. Francis G. Brink, who had experience training Chinese troops in long-range patrolling and operating behind enemy lines. After a 10-day exercise with the Chindits, Galahad was sent to northern Burma in January 1944 to link up with Stilwell’s force comprising Chinese, Kachins (Burmese natives), Indian, and British forces.

The Brutal Attrition of Jungle Warfare

From February 1944 until April of that same year, the Marauders had fought bitter battles at Walawbum, Shaduzup, Inkangahtawng and Nhpum Ga. In addition, they had over 30 minor engagements and inflicted numerous casualties upon the elite 18th Japanese Division. The unit had compiled a remarkable record in a short period of time. After the Walawbum campaign, where the infantrymen pushed the enemy from their positions and killed and wounded over 800, Merrill commented, “Between us and the Chinese, we forced the Japanese to withdraw farther in the last three days than they have in the last three months of fighting.”

Unfortunately, the rigors of jungle warfare had taken their toll on the Marauders. Since beginning the campaign, the riflemen had marched an astonishing 750 miles in some of the worst terrain in any theater of operations. Disease and battle casualties had drastically reduced the unit’s combat effectiveness. Out of the nearly 3,000 men, only 1,400 remained— and some of these soldiers needed to be evacuated. Men could barely walk and suffered from such severe dysentery that they slit the seats of their trousers so they could keep moving. Because there were no reinforcements for them, Stilwell augmented the force with Kachins and Chinese troops for a total strength of 7,000. Stilwell pressed the Galahad force even harder and gave them a new assignment: take the airstrip at Myitkyina, code-named Operation End Run.

Preparing for Operation End Run

A complete reorganization took place for the Myitkyina operation. The 2nd Battalion was the most depleted of the lot after sustaining numerous casualties at Nhpum Ga. With just enough men to form two rifle companies, 300 Kachin guerrillas boosted their numbers. This was designated M Force under Lt. Col. George A. McGee, Jr.

Colonel Charles N. Hunter was given the 1st Battalion with the Chinese 150th Regiment from their 50th Division. Several 75mm pack howitzers were added to Hunter’s command, which was named H Force.

Lastly, the 3rd Battalion and the Chinese 88th Regiment, 30th Division was consolidated into K Force and commanded by Colonel Henry L. Kinnison, Jr. They were given the artillery from the Marauders for additional firepower for the upcoming campaign. Merrill, who had a heart attack after Galahad’s second operation, had recovered sufficiently and rejoined the Marauders.

In late April, Stilwell arrived at Merrill’s headquarters at Naubum to confer with him on the upcoming operation. The plan had H and K Forces traveling north to Taikri, then turning sharply east, traversing the Kumon Mountains, and arriving at Riptong. From there, both groups would make their way south all the way to Myitkyina. M Force would move parallel to the others, acting as flankers to stop any enemy troops from advancing northward to strike at H and K Forces.

On April 28, K Force began its arduous trek into the Tanai Valley and over the Kumon Range. Several days later, H Force jumped off. The march was approximately 65 miles, but one-fifth of it was over the toughest ground ever encountered by the Marauders. To make matters worse, the trail the men were to use had not been traveled in 10 years. A group of Kachins and 30 laborers, under the leadership of Captain William A. Laffin and 2nd Lt. Paul Dunlap, took the point to clear the unforgiving underbrush for the rest of the party.

To add to their misery, torrential monsoon rains began. Rain fell every day, and the humid tropical air was unbearable. The loads had to be taken off the pack mules and carried by the soldiers up the steeper cliffs for fear that the animals would slip and fall. In spite of this, Khaki Team alone had 15 mules lose their footing and, in some cases, fall hundreds of feet to their deaths.

The other Marauders experienced the same harsh elements as they slowly snaked their way toward their objective. In his book, The Marauders, former member Charlton Ogburn, Jr., relates the misery of the trek: “We were scarcely ever dry. When the rain stopped and the sun came out, evaporation would begin. The land steamed. The combination of heat and moisture was smothering. You had to fight through it. For those most weakened by disease, it was too much. For the first time you began to pass men fallen out beside the trail, men who were not just complying with the demands of dysentery—we were used to that—but were sitting bent over their weapons, waiting for enough strength to return to take them another mile.”

The Battle of Riptong

On May 6, the advance elements of K Force arrived at Riptong, where they knew a sizable Japanese garrison was stationed. Colonel Kinnison opted to envelop the enemy. He sent 1st Lt. Logan Weston and his platoon to hack at the dense jungle on the south side of the village. While Logan’s men were establishing their blocking position, the Khaki and Orange Teams proceeded in a wide arc to the south to further cut off any escape attempt by the Japanese. Orange Team arrived on the heels of Khaki and set up its 60mm and 81mm mortars to support the Chinese infantry ordered to seize the village.

Enemy snipers soon began harassing the Marauder’s positions with rifle fire. Private Charles A. Page was seriously wounded and died four days later. Private Anthony Colombo later said, “We knew that he was going to die. I was 19 years old and he was 18, and from what I understand it was his birthday. I just sat and held his hand as he lay there.”

On May 7, the sounds of the Chinese bugles of the 88th Regiment permeated the air as two companies prepared to attack Riptong. Moving on the village, the Chinese took extensive casualties as the enemy opened up with mortars and automatic weapons fire. The Marauders supported the Chinese with machine guns and mortars but had to be careful not to drop shells on the advancing Chinese infantry. Japanese defenders assaulted the Marauders’ roadblock in an attempt to breach the perimeter and make their escape but were driven back.

By May 9, the Chinese had successfully taken Riptong. One Marauder medical officer estimated that “about one-third of the two companies of Chinese became casualties.” However, it became evident that they had inflicted heavier casualties on the Japanese when one prisoner said under interrogation that 90 of his comrades were killed and only 40 managed to escape. Later, Marauder patrols would kill 36 of these enemy soldiers.

“Japanese Defenses Dominated All Approaches”

The battle at Riptong had undoubtedly alerted the Japanese to a sizable enemy force in the area. Colonel Hunter’s H Force attempted to make a dash for Myitkyina, a mere 35 miles away. To protect Hunter’s flank, K Force was ordered to the village of Tingkrukawng, to assist a group of Kachins and Gurkhas embroiled in a battle there.

By the morning of May 12, lead elements of K Force had reached the outskirts of Tingkrukawng. One of the scouts erroneously thought he saw a group of Chinese on the trail and he greeted them, only to find out they were Japanese when they quickly scattered. Soon Khaki and Orange Teams, together with the Chinese 89th Infantry Regiment, prepared for the attack.

As the infantrymen pressed forward, enemy machine-gun bullets wounded several men, nearly killing the cameraman accompanying them. Orange Team’s K and L Companies attempted to reach the village but met stiff resistance. Colonel Kinnison soon estimated that well-entrenched battalions of Japanese were in the village.

As American and Chinese mortars tried to soften the enemy’s defenses, riflemen scurried to envelop the Japanese but met with no success. By late afternoon, the Marauders located the Japanese fortifications. In his book, Spearhead: A Complete History of Merrill’s Marauder Rangers, author and former Orange Combat Team surgeon James E.T. Hopkins wrote, “The entire battle area was covered by dense jungle with massive hardwood trees and dense low vegetation, including much thick and heavy bamboo. The Japanese defenses dominated all approaches.”

Even medical personnel were susceptible to Japanese fire as Hopkins would soon find out when the battle resumed the next morning. As the team of doctors was operating, a Japanese machine gun let loose devastating fire on the makeshift operating room. Hopkins describes the courage of several muleskinners trying to silence the weapon: “Pfc. H.T. Pausch’s heroic action cost him his life, and that of Pvt. Clayton A. Vantol resulted in his being wounded. These two and several other muleskinners worked their way toward the gun and, at about fifty yards’ range, a burst from the gun caught Pausch in the chest, causing his instant death.” The deadly machine gun nest was eventually wiped out by the Marauders.

“Roll in and Swing on ‘Em”

Realizing he could not dislodge the enemy with the troops he had, Kinnison was satisfied that he had held up the enemy long enough, and Hunter’s group was well on its way to Myitkyina. Under the protective umbrella of an artillery barrage, K Force slipped away and set out to link up with H Force.

On May 13, Merrill fired off a message to Stilwell that read: “Can stop this show up till noon tomorrow, when die will be cast, if you think it too much of a gamble. Personal opinion is that we have a fair chance and that we should try.” Stilwell concurred and penned in his diary: “Hunter expected to give us the 48-hour signal tonight. I told Merrill to roll in and swing on ‘em.”

Hunter’s weary H Force, consisting of the 1st Battalion of Merrill’s Marauders, the 150th Chinese Regiment, the 3rd Company Animal Transport Regiment, and a detachment from the 22nd Division artillery, trudged into the village of Lazu where Hunter immediately formulated plans for the capture of Myitkyina airfield. H Force would conduct the main assault, with Colonel Kinnison’s K Force on the eastern side. Colonel McGee’s M Force, which had just arrived after an arduous trek through the jungle, was to shield Hunter’s western flank.

The Kachin lead scout, trained by OSS (Office of Strategic Services) Detachment 101, led the column on a torturous trail so they could arrive at their destination unseen by the Japanese. Misfortune struck when the knowledgeable guide received a bite from a venomous snake. When the Kachin’s foot became infected, several Marauders sucked poison from the wound to save his life. This rudimentary medical practice was successful, and they placed him on Colonel Hunter’s horse so they could continue on to Myitkyina. The account from the official history states, “Without his guidance, the Marauders would have had difficulty finding their way in the dark through the intricate maze of paths.”

Taking the Air Strip

As the group proceeded, Hunter took every precaution to hide his movements from the enemy as they neared their objective. He had his men confine the inhabitants of the village of Namkwi, just four miles from the airfield, within his own perimeter. Many of the natives were known to be loyal to the Japanese.

Prior to the attack, Hunter wanted intelligence on the condition of the airstrip and the disposition and number of its troops. Sergeant Clarence E. Branscomb, from White Combat Team, a savvy veteran of the Solomon Islands campaigns, led a six-man patrol to reconnoiter the area. Taking a radio, Branscomb’s patrol headed out. On the way, the men “killed a [bottle of] Canadian Club” given to them by Colonel Hunter. Upon reaching the field, the Marauders witnessed the enemy repair crews leaving. Apparently, the Japanese customarily worked on the field until midnight and then withdrew to their bunkers to afford them better safety from the constant air attacks.

In 1989, in a letter to The Burman News, Branscomb relates what happened next:

“I picked up the radio and started walking down the middle of the runway, thinking if those emplacements were occupied we’d soon find out …”

After keying the microphone, because the radio could only receive but not send voice traffic, Branscomb notified headquarters that the coast was clear to send in gliders carrying Chinese troops for the impending assault.

On May 17, Colonel William L. Osborne was to jump off at 10 am with the 1st Battalion of the Marauders and the Chinese in trace. Arriving at the southwest end of the airstrip, he was to leave the 150th Regiment there to seize the field at a predetermined signal while he and the battalion made their way to Pamati to capture a ferry launch that traversed the Irrawaddy River.

Within the hour, the Marauders had secured Pamati and the nearby ferry. Red Combat Team remained at the ferry while White Combat Team returned to the airfield to capture Zigyun, the main ferry terminal for Myitkyina. The Chinese, after seeing the red flare signal, moved on the airstrip and quickly overran the enemy positions. With bugles sounding the charge, the Chinese took the Japanese completely by surprise, and the airdrome soon belonged to the Allies.

After the bridge at Namkwi was blown by the Kachins, the Chinese established defensive positions on the southeast end of the field. The code words, “In The Ring,” were sent, informing Merrill that the strip was ready to be used.

Communicating between the various units soon became a problem. Seven C-47s, towing gliders with engineering supplies and soldiers from the 879th Engineer Aviation Battalion, began their approach to the airfield with no advance warning to the working parties on the ground. Gliders landed and skidded in all directions as men ran to escape injury. Luckily, no one was hurt.

Soon, Chinese units began arriving as well. The 2nd Battalion, 89th Regiment, and a battery of antiaircraft guns landed before the rains struck. Again, Hunter could not reach this unit to disperse the troops around the airfield. However, the items most desired by the Marauders—food and ammunition—did not arrive.

Health Crises Among the Marauders

On May 18, two battalions of the 150th Chinese Regiment attacked Myitkyina itself from the north while White Combat Team seized Rampur. The Chinese assault was moving well as they took a railroad station, but they soon bogged down when they became involved in confused fighting and had to retire. The Chinese withdrew and set up a perimeter 800 yards west of Myitkyina.

K Force was moving toward Myitkyina from the north and was ordered to attack the village of Charpate, located about five miles from the airfield. After a brief firefight with a lone Japanese machine-gun emplacement, the hamlet was secured. K Force’s ranks were rapidly thinning because of disease. As Dr. Hopkins states in his book Spearhead, “A new combination of complaints was now surfacing. Numerous men were complaining of severe headaches that persisted in spite of aspirin. The men also had skin rashes and swollen glands in their groins. We suspected that we were now seeing early cases of scrub typhus, the frequently fatal disease about which we had been warned when we were halfway across the mountain range.”

Despite the health crisis in the 3rd Battalion, the Marauders patrolled the area and kept a constant vigil for any Japanese. Merrill and Hunter situated their forces to block the enemy from reinforcing their small garrison at Myitkyina. The 3rd Marauder Battalion blocked the north and northwest, while the 88th and 89th Chinese Regiments held a perimeter that ran from Charpate southwest to the railroad. The 2nd Marauder Battalion formed its lines between the railroad and Namkwi to the south. The 1st Marauder Battalion was protecting the airfield with the 150th Chinese Regiment, which also had the responsibility of defending the western side of the city.

Merrill disbanded H, K, and M Forces and had the Marauders stay in their own battalions under the command of Colonel Hunter, while the Chinese were to operate independently. When he arrived at the airstrip and saw his men, even Merrill remarked sympathetically, “[They] were pitiful but still a splendid sight.”

When this was completed, however, Merrill sustained another heart attack and had to be evacuated. Command of the depleted Marauder battalions fell to Colonel John McCammon.

The Japanese Counterattack

Even though the Allies had established blocking positions around Myitkyina, the Japanese were soon able to bolster their small force near the airfield with an additional 3,000 to 4,000 men from the surrounding villages. By the end of May, the enemy began offensive operations to retake the airdrome.

The reason for the rapid buildup of enemy forces was simple: the Marauders were spent both physically and emotionally. The medical report states, “Many of them were seriously ill and they were so tired, dirty, and hungry that they looked more dead than alive. They suffered from exhaustion, malnutrition, typhus, malaria, amebic dysentery, jungle sores, and many other diseases resulting from months of hardship in the tropical jungle.”

Morale was also extremely low. In an article entitled “Burma Campaign Phase I,” author C. Peter Chen noted, “The harsh conditions the Marauders fought in were made worse by their constant fighting in the jungles without adequate rest and recuperation. Colonel Hunter made a report of complaint to General Stilwell, noting that his men had been overworked…. Even promises that they would not be used as spearheads for Chinese troops were broken, as shown by the current campaign at Myitkyina. Nevertheless, the Marauders stayed in the campaign, and fought on valiantly.”

On May 23, a company-size enemy force breached the 3rd Battalion’s lines at Charpate. Visibility was made worse by a driving rain, and before the Marauders realized it, the enemy was within their lines.

Private First Class Stephen “The Russian” Komar was ripping into the attackers with his Thompson submachine gun when he was struck in the arm. He was draped with the intestines of one Japanese soldier as he continued firing. Hand-to-hand combat ensued, with a few Marauders being killed by enemy bayonet wounds. In the end, however, the defenders drove the enemy from their position. Five Marauders were killed and another six wounded while the Japanese sustained 15 dead and 35 wounded.

Soon, the Japanese occupied Namkwi and set out to rebuild their fortifications. Even with some replacements from engineer battalions, the Marauders were finished as an effective fighting force. Additional Chinese units arrived as the 2nd and 3rd Marauder Battalions were evacuated. Only the 1st Battalion, also a mere shell of its former self, remained at Myitkyina until August 3, when the town was finally wrestled from the Japanese.

A Distinguished Unit Citation for Merrill’s Marauders

Of the nearly 3,000 original Marauders, only 1,300 were there at the Myitkyina campaign. Of this, nearly 700 were evacuated during the last two weeks of May. By August 3, when the remnants of the Marauders finally left Myitkyina, only 200 were left. Disease and death had taken their toll. The Chinese lost 972 killed and 3,184 wounded. The Americans had 272 killed, 955 wounded, and 980 medically evacuated for various illnesses. The Japanese fared worse, losing over 3,000 men. The outfit received a Distinguished Unit Citation (renamed Presidential Unit Citation in 1966) for its outstanding service in the CBI Theater.

The Marauders tallied an impressive record in the nearly five months of jungle fighting in Burma. The unit history proudly states, “The attack on Myitkyina was the climax to four months of marching and combat in the Burma jungles. No other American force except the First Marine Division, which took and held Guadalcanal for four months, has had as much uninterrupted jungle fighting service as Merrill’s Marauders. But no other American force anywhere had marched as far, fought as continuously or had to display such endurance, as the swift-moving, hard-hitting foot soldiers, of Merrill’s Marauders.”

Al Hemingway is a frequent contributor to WWII History and a Vietnam veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments