By Robert Suhr

Philip of Valois, for long have we made suit before you by embassies and all other ways which we knew to be reasonable, to the end that you should be willing to have restored unto us our right, our heritage of France, which you have long kept back and most wrongfully occupied.”

With this letter to his distant relative, Edward III of England responded to attacks by the French king on Edward’s Continental lands. What began as a conflict over differing national interests became a century-long war of succession to the French throne.

Charles IV of France died without an heir in 1328, leaving two aspirants to the throne: Edward, son of Charles’s sister Isabella, and Philip of Valois, a nephew. The Twelve Barons of France chose Philip because they did not want a foreign king ruling over France. Scholars later used the logic of an old French law that prohibited a woman from inheriting property as basis for rejecting Edward. At first Edward seemed to accept the decision and, as lord of Gascony in what is now southwestern France, swore fealty to Philip.

During the first decade of his reign, Edward sought revenge for his father’s defeat in Scotland. His grandfather, Edward I, conquered Scotland, but Edward II lost it at Bannockburn in 1312. The Scottish army of Robert Bruce routed the English army in a humiliating defeat that was the nadir of English military fortunes.

Robert died in 1329, leaving his 12-year-old son, David, as king. At first Edward supported Edward de Baliol’s claim as king of Scotland. As Baliol’s fortunes faltered, Edward marched north in 1332 with his own army.

At Halidon Hill, Edward earned his first major victory. While besieging Berwick Castle, he maneuvered the Scottish army to attack on ground of his choosing. He deployed with the dismounted men-at-arms in the center and archers on the flanks. Archibald Douglas led a larger Scottish army through a marsh into the teeth of the English defenses.

The 14th century was the twilight of knighthood and chivalry. A small part of every English army was composed of men-at-arms, a generic term describing knights and other warriors on horseback. In battle they dismounted to fight on foot.

The backbone of the English army was the archer. At the end of the 12th century, Edward I adopted the Welsh longbow. It had a killing range of 300 yards and could penetrate plate armor at closer range. Edward III used his archers to canalize the attackers into a narrow front. Those not killed by the arrows were easily hacked by the men-at-arms.

The six-foot-high longbow was a “self” (as opposed to composite) bow, preferably made from Spanish or Italian yew. The “draw” of the longbow is not known, but is estimated to approach 100 pounds. Firing six to 12 arrows per minute, a body of longbowmen could place a devastating number of arrows on an enemy. That rate of fire, however, created a need for constant resupply.

Edward’s success at Halidon Hill forced 12-year-old King David to flee Scotland for France. Philip threatened Edward and tied the fate of Gascony to Scotland.

About the same time, Philip accused Robert of Artois of committing murder to snatch the lordship of Artois, an area that is now the French/Belgian border around Calais and the Somme River. Robert fled to Windsor where he joined his boyhood friend, Edward. While at the English court he encouraged Edward to claim the French throne. Philip accused Edward of harboring his enemies.

While Edward’s eyes were to the north, Philip’s were to the east. The Pope persuaded Philip to launch a crusade against the Turks. To transport his army to the Middle East, he assembled a large fleet at Marseilles.

Philip vs. Edward

With the fortunes of an independent Scotland fading, Philip threatened England by transferring his fleet from the Mediterranean to the Channel. In 1335, the situation deteriorated further as Philip announced he would help the Scots against Edward. Pope Benedict XII delayed the inevitable conflict by negotiating a two-year truce between Philip and Edward.

Philip was known as a brave knight, but he left much to be desired as both a general and a king. Throughout his reign he attacked those in France he thought were his enemies. Not only did he drive Frenchmen into the English camp, but he lost the support of others.

While Philip moved against his enemies in France, Edward bought allies in The Lowlands. Philip had already alienated Flanders (just up the coast from Artois) by banning the importation of English wool. The pro-French Louis of Nevers, Count of Flanders, was expelled and replaced with pro-English leaders. Edward also strengthened commercial ties with new treaties.

With Flanders allied to England, Edward had a strategic advantage. If Philip moved against Gascony in the far south, Edward could use The Lowlands to open a second front close to Paris.

Philip had moved against England first. In 1337 he opened the war by announcing that Edward’s Continental lands were forfeit. But taking possession of Gascony would be difficult. An English army led by the Duke of Lancaster frustrated Philip’s efforts to seize control of the region.

In June 1338, French privateers burned Portsmouth. Between 1338 and 1340, they attacked England from the Thames estuary to Cornwall. The French intent may have been to force Edward to defend England, giving Philip a free hand to operate on the Continent.

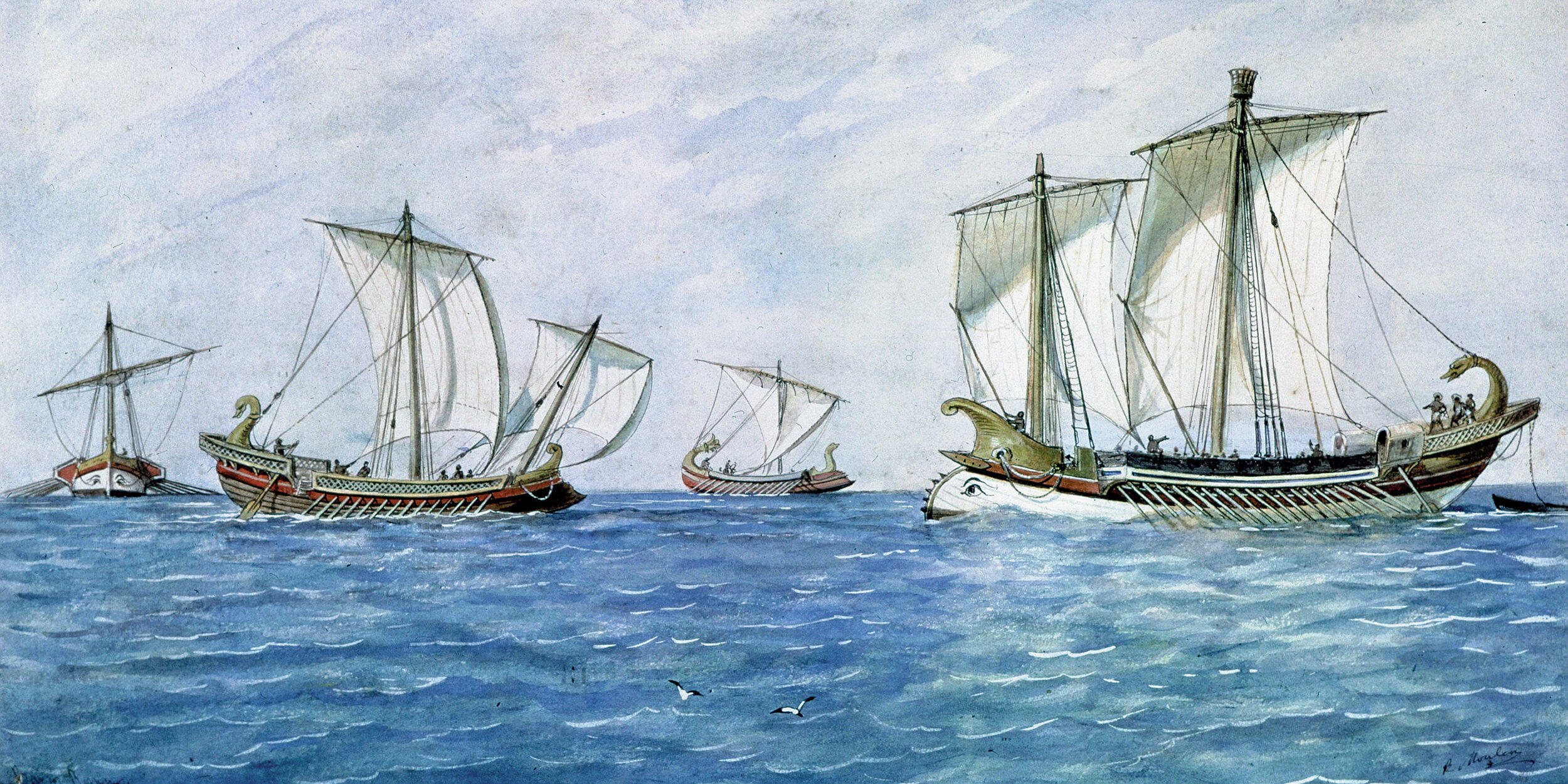

The grand fleet Philip had collected for his crusade moved into Flanders where it threatened Edward’s line of communication with his allies on this part of the Continent. The fleet anchored at Sluys at the mouth of the River Zwin under the command of the Breton buccaneers Hugnes Kiriet and Nicholas Babuchet and the most famous admiral of the era, Barbenoire from Genoa.

On June 23, the English fleet attacked. Rather than sail into the open where they could use their superior power, the French chose to fight as though it was a land battle. The English found the French ships chained bow-to-stern in four rows.

The Battle Was Such a Disaster, No One had the Courage to Tell Philip…

Edward had the English ships chained in pairs—a ship of infantry next to a ship of archers. The English longbowmen swept the decks of the French while suffering few casualties themselves. Only the fourth line managed to flee. After an all-night running battle, Barbenoire escaped with 24 ships. The battle was such a disaster than no one at the French court had the courage to tell Philip. It fell to the court jester to tell the king that the English were cowards because they did not jump overboard as did the brave French sailors.

Although the Battle of Sluys gave Edward command of the seas, he could not follow up on that victory. The siege of Tournai in The Lowlands failed in 1340 when Edward’s allies agreed to a truce proposed by Jeanne de Valois, Philip’s sister and Edward’s mother-in-law. Campaigns in Brittany and Gascony brought tactical victories but no strategic gain.

Another French refugee joining Edward early in the war was Godfrey de Harcourt. Following a fight with the Bishop of Bayeux, Harcourt fled to his estates in Normandy. After Philip executed those who helped him, Harcourt sailed to England where he offered his services to Edward.

By this time the Flemish had forced Edward’s hand. They understood that they could not oppose Philip without suffering ecclesiastical penalties because he was their king, but they discovered a loophole. By having Edward declare himself king of France, they could transfer their allegiance from one king of France to another. Edward could then keep their support.

With all this in mind, in 1346 Edward prepared to invade France with many options available to him. Philip had sent a large army under Prince John of Normandy against Lancaster in Gascony. Edward could sail there to help protect his possession in the south of France. About the same time he was ready to sail, an Anglo-Flemish army marched from Ypres in Flanders toward Paris from the north. With control of the seas, Edward could help that army, or land anywhere between Flanders and Gascony.

Most contemporary chronicles claim Edward originally intended to join Lancaster in Gascony. The ships sailed west for three days before the wind changed and threw the fleet back on the Cornwall coast. Harcourt suggested Edward land in Normandy, a land rich and defenseless since Philip had stripped the area of troops to fight Lancaster.

Edward took the advice and sailed to Cotentin with about 15,000 men. Before landing at La Vaast on July 12, he knighted his son Edward and others.

Edward’s strategy was to conduct a raid called a chevauchée. The intent was to make war on civilians to destroy French morale. If Philip did nothing, his prestige and support would weaken. If he acted rashly, he might try to fight Edward before assembling a significant force.

2,500 Soldiers Roaming the Countryside, Looting and Burning

In France, Edward organized his army into three “battles.” He commanded the largest in the center. He appointed Godfrey de Harcourt marshal of the right battle and the Earl of Warwick marshal of the left.

Edward wanted to join the Anglo-Flemish army for an attack on Paris. His initial route followed the coast southeast from La Vaast to St. Lô. During the first 10 days, Harcourt’s 500 men-at-arms and 2,000 archers roamed the countryside, looting what they could carry off and burning what they could not. At night they fell back on Edward’s position. Warwick’s battle marched on the English left, keeping in touch with the English fleet following the coast.

Edward crossed the River Vire at St. Lô and continued southeast from there. Fourteen miles from St. Lô, Edward abruptly changed direction to march northeast toward Caen. The army moved in the same formation as before, Warwick on the left, Harcourt on the right, cutting a path of destruction 12 to 15 miles wide.

As he approached Caen, Edward sent a cleric forward with a message demanding that the town surrender. If the town did, he would respect the lives and property of the people. The Bishop of Bayeux answered by tearing up the letter and throwing the cleric in prison.

Caen had a castle with a moat on two sides. The new town lay on an island in the Orne River with the old town between it and the castle. Edward chose to attack the weakest of the three targets, the old town. His men advanced in three columns with the marshals’ banners in front. They swept through the lightly defended old town and wheeled toward the new town. At the bridge of St. Pierre, stiff French resistance stopped the attack, but at another bridge the English pushed across to turn the French flank.

Two French leaders at the bridge of St. Pierre were Count Eu, the constable, and the Earl of Tancarville, the chamberlain. They retreated toward the town but were trapped outside the gates. Well-known among the chivalry of Europe, they could expect to be ransomed if captured but they were afraid they would be caught and killed by archers who did not know them. Riding toward the gate was Sir Thomas Holand whom they knew from campaigns in Grenada and Pressia. They called to him as he passed, then surrendered along with 25 knights.

After losing 500 men in Caen to civilian attacks Edward decided to burn the town, but Harcourt stopped him. Many people in the town would resist, costing the English more casualties, he argued. Harcourt continued by saying that Philip was so unpopular in the area that if Edward left the town alone, the people would support him within a month. Thus Edward spared Caen.

Philip had not been idle while the English ravaged Normandy. Word of the invasion arrived at his chateau at Becoiseau shortly after Edward landed in France. He summoned all the nobles who were not with Prince John and asked for help from his friends.

Coming to join him was John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia. Luxembourg was the most renowned fighter in Europe. Between wars, he participated in many tournaments for the pure joy of fighting. In one, he received an injury that left him blind in one eye.

The Legendary Oriflamme

Along with Luxembourg was his son, Charles, King of Germany, and James, King of Majorca. Answering Philip’s call were many of the greatest lords and knights of France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Bohemia.

Philip moved to Paris, then to the abbey of St. Denis north of the city to retrieve the Oriflamme. This was not the banner of the kings of France, which was the fleur-de-lis, but a national treasure, a special battle flag brought out only in times of emergency. It was first mentioned in 1124 but some legends trace it back to Charlemagne (and even Constantine).

Before receiving it, the bearer had to take the sacraments and swear to protect it. Philip selected Guy, Sieur de la Tremoille, to carry it during this campaign. A golden staff supported a red silk banner that ended in two (or possibly three) tails. Green tassels (or fringe) lined the edges.

Edward’s direct route to Flanders lay across the Seine at Rouen. Philip placed Jean Count of Harcourt, Godfrey’s older brother, in command there. Despite this, Edward continued in the general direction of Rouen, but other than sending Godfrey toward it on a reconnaissance in force made no effort to cross the river there.

At Elbeuf Edward changed directions, abandoning plans of marching directly toward Flanders. Instead, the English army followed the south bank of the Seine toward Paris in hopes of finding a crossing. By moving in that direction, Edward hoped to mislead Philip into thinking his objective was the French capital.

As the English army marched east, the French army shadowed it along the north bank of the river. By then, Philip had arrived to command the army in the field. As his army moved closer to Paris, he fell for Edward’s ploy. Avoiding the twists and turns of the river, his army continued to Paris ahead of Edward.

The English had no luck finding a place to cross the Seine until Poissy, 10 miles from Paris. Philip paused to destroy the bridge, but only left behind a small force to guard the piles still rising from the water.

Edward sent men across in boats to drive off the French. With the far bank secured, the English labored for days to rebuild the bridge. To continue the illusion that he intended to attack Paris, Edward sent his son in that direction. The ruse worked as Philip moved around the perimeter of Paris, attempting to defend the unwalled city.

While Philip still protected the capital with most of his army, he sent a small force forward. The French attacked the English on the north bank, but a counterattack by the Earl of Northampton, Edward’s constable, killed 500. Although he knew the English were trying to cross the river, Philip remained in Paris.

Edward sent his marshals toward Paris to reinforce Philip’s fears that he still intended to march in that direction before beginning a race for the Somme and the Anglo-French army to the north. When Philip saw Edward’s direction, he, too, headed north. The two armies arrived at the Somme at about the same time, the French at Amiens and the English 50 miles west.

A Desperate Edward Promised Freedom to Any Prisoner Who Helped Him

Philip believed he had Edward trapped south of the river. Philip already controlled the bridges so he could advance on either bank. To ensure that Edward remained south of the Somme, he sent men to guard the fords. The only remaining place to cross was at Blanche-Tache below Abbeville. Philip sent Sir Godemar de Fay there with 1,000 men-at-arms and 5,000 foot soldiers, including some Genoese crossbowmen.

Edward decided he was trapped about the same time Philip did. He ordered the marshals to take 1,000 men-at-arms and 1,000 archers west to try to find a place they could cross. At Pont-à-Remy, they found a bridge occupied by a large number of French knights. The English dismounted and tried to fight their way across but conceded defeat at noon and withdrew. They marched further west to Long-en-Pontrieu, but the bridge there was too strongly fortified, as was the one at Pequigny.

In desperation, Edward had his prisoners brought to him. He offered to free any man (and 20 of his friends) in return for information about a crossing below Abbeville. One peasant, Boin Agace, told Edward about Blanche-Tache. At Blanche-Tache the river ran over white chalk so hard carriages could pass over and so wide men could cross 12 abreast. The problem with crossing there was that they could only ford when the tide was out.

At midnight Edward ordered the trumpets to sound. The army arrived at the ford at daybreak, but the tide was full. The English remained trapped on the south bank until noon. By the time the tide had receded, the French under Godemar de Fay lined the far bank.

Pursued by 40,000 of Philip’s Men

Edward ordered his marshals to force a passage with his archers covering the attack. The longbowman led the advance. The initial fight was between the archers in the river and crossbowmen on the river bank. Bolts from the crossbows hit the Englishmen in the water, but with their higher rate of fire, the archers drove the crossbowman back. At this time the English men-at-arms passed through the ranks of the archers to the cry of “Dieu et Saint George!” Believing that 100,000 Frenchmen were approaching from the rear, the English fought desperately, driving their French counterparts back from the river.

Indeed, the French were approaching south of the Somme and, although Philip commanded only about 30,000 to 40,000, his troops nevertheless vastly outnumbered Edward’s. Already French scouts had made contact with the English rear guard and reported that the English were trying to force their way across. The French vanguard hurried forward.

Attacks by the longbowmen followed by men-at-arms took a toll on the French at the ford. De Fey retreated when he realized he could no longer hold the ford. His mounted men made it to Abbeville, but his foot soldiers were less lucky. The English chased them for a couple miles, killing all they could catch.

Edward had most of his army across the Somme when knights under Count John of Hainaut and King John of Bohemia fell on the English rear. They killed many English and captured some wagon, but the army escaped.

Philip pushed forward as quickly as he could, but by the time he arrived at Blanche-Tache, the English were on the other side of the river. He held a council with his marshals who told him his army could not cross. The tide had come in and it would be another six hours before they could make the transit. Philip withdrew to Abbeville for the night. Meanwhile, Edward gave Agace his reward and released both him and his companions.

Edward’s sense of urgency ended as soon as he crossed the river. At a minimum, he had half a day’s lead on Philip if the French stayed at the ford. It was somewhere near the Somme that Edward abandoned the idea of joining the Anglo-Flemish army. He may have received word that the campaign in the north was failing—the same day Edward crossed the Somme, the allies ended the siege of Bethune and withdrew to Flanders.

In any event, on the morning of Friday, August 25, Edward sent his marshals to the left and right. One burned and devastated the countryside as far as the gates of Abbeville before falling back. The other column reached the town of St. Esprit de Rue. Then the army assembled in the Forest of Crécy.

Edward decided to fight Philip there. “Let us stand here till we have seen our enemy, for I am now in the inheritance of my mother, which was given to her on her marriage, and I should like to contest my quarrel here with my enemy Philip de Valois.”

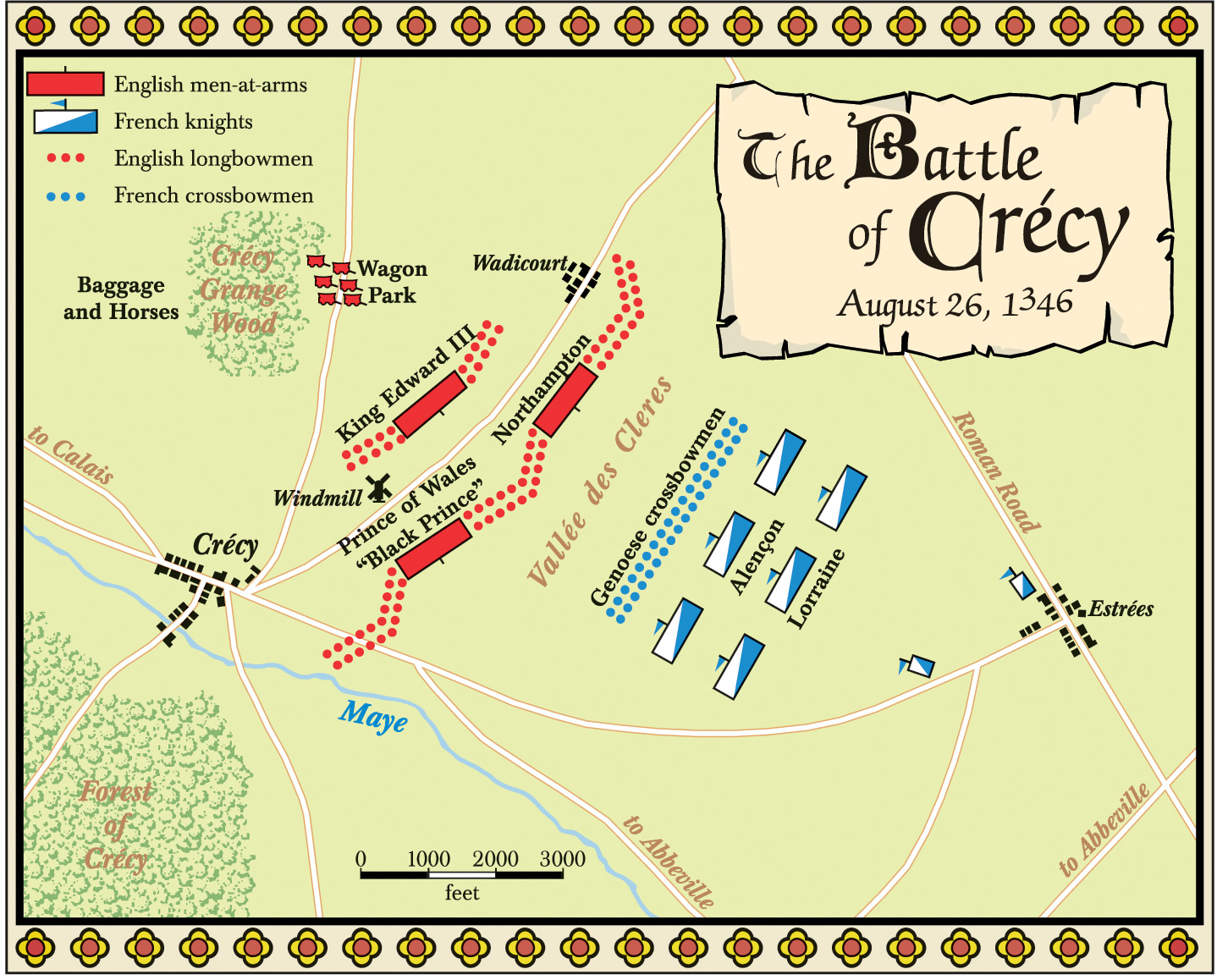

Edward set his azure and gold silk pavilion on a hill next to a windmill. Overhead he flew his personal banner upon which he had placed the fleur-de-lis of France. On his left was the village of Wadicourt and on his right, Crécy (or Cressy). At the base of the 200-foot hill was the Vallée aux Clercs. The slope of the hill was gentle at the bottom, but as it approached the English position, the gradient became sharply steeper.

The Eve of Battle

Edward asked his marshals and others for advice, and then deployed the army accordingly. The position they chose would force the French to advance on a narrow front that would negate the French numerical advantage. The terrain gave Philip no room to deploy his army and advance in broad array.

On the eve of battle, Edward held a dinner for his senior nobles. He ordered his people to rest but to be ready, arrayed for battle as soon as the trumpets sounded. When the nobles had left, Edward retired to his oratory where he prayed until midnight.

In the evening, Philip held a grand banquet to which he invited all the royalty and major nobility. These were men who had been brought up believing in the “Song of Roland” and the legends of chivalry. Philip seems to have recognized the rivalry among them. In a speech after dinner he asked them to put aside their jealousies in the coming battle.

At dawn, the English leaders moved their troops into position. Edward emerged from his pavilion accompanied by Prince Edward, who was wearing the black chain mail that would give him the nickname “the Black Prince.”

Edward divided his army into three battles. Prince Edward nominally commanded the first battle on the right, the position of honor. The real commanders, though, were the Earls of Warwick and Oxford and Godfrey de Harcourt. Later, when Edward created the Order of the Garter in 1348 to celebrate the ideal of chivalry, Prince Edward and 12 others who fought with him this day would be among the original 26 members.

The Earls of Northampton and Arundle commanded the second battle on the left, while King Edward commanded the third in reserve on the hill behind the first. From the windmill he could watch the battle develop.

With 800 men-at-arms and 2,000 archers, Prince Edward’s battle was the largest formation; the reserve was almost as large at 700 men-at-arms and 2,000 archers. Perhaps because he knew honor would force the French to attack his right, the left battle had only 500 men-at-arms and 1,200 archers.

The battle formation was one that had served Edward well in the past. Dismounted men-at-arms were in the center with the archers on the flanks in a staggered formation that allowed all the men to fire simultaneously. Archers filled in the gap between the two battles and Welsh infantry waited in reserve immediately behind the men-at-arms. Behind the front lines, Edward placed a few primitive cannon.

The Calm Before the Storm: Edward’s Troops Await the Coming Battle

After his army had been drawn up, the king rode slowly from rank to rank, giving speeches to boost morale and admonishing the earls, barons, and knights to guard well his honor and defend his territorial rights. He ordered the men to maintain their ranks and not to leave them to take prisoners or to attack their enemies.

Edward’s army was ready for battle, but the enemy had not arrived. Thus Edward had his men sit down and remove their helmets so they would not be tired when the enemy arrived. And he ordered food brought up so they could eat.

At dawn, Philip heard mass within the Abbey of St. Pierre at Abbeville with the great lords. His army was packed with nobility, including four kings; Philip’s brother Charles, who was the Earl of Alençon; and the Counts of Flanders and Hainaut. Before the army started that morning, Philip gave Hainaut a powerful black horse. Hainaut in turn loaned it to Sir Thierry de Senseilles to carry his banner.

Philip issued no orders for a battle before his army marched. Five miles from Abbeville, the nobles with him suggested he send three or four knights out to discover the position of the enemy. The four he chose rode close to Crécy but the English did not fire on them. When they returned, Philip commanded Le Moine de Basele to tell what they had seen.

“Sire, I will speak if you wish it. We have ridden and observed well the English, and you should know that they are drawn up in full array in three columns, and there is no sign that they mean to retire.”

The report also revealed that the French army had been marching somewhat in the wrong direction. With information as to the exact location of the English, it changed directions to march directly to Crécy.

As they approached Crécy, de Basele suggested that Philip halt the army so it could close up. Realizing the English would not run away that day, the French king sent one marshal forward to stop the front of the army, and another rearward to order the remainder to close up. Those in front halted, but those in the rear said they would not halt until they were as far forward as the others. When those in the advance saw the others still moving, they started forward again.

“À La Mort, à La Mort!”

This caused the van of the French army to encounter the English. They in turn attempted to fall back, but this created confusion. Frenchmen immediately behind thought there had been fighting and that they had been defeated. The French infantry was still seven miles from the English position but they pulled out their swords, crying out, “À la mort, à la mort!” They were still too far from Crécy to see anything.

Then, as the bulk of the French army drew up, a thunderstorm swept across the landscape. When the skies cleared, the French advanced with the sun in their eyes.

The Earl of Alençon commanded the French approach. With him were Philip’s personal force of 6,000 Genoese crossbowmen. Alençon ordered them to advance to soften up the English while the French chivalry closed up behind. Unfortunately, the crossbowmen were exhausted, having marched 15 miles carrying their heavy crossbows. They complained to their constable that they were in no condition to fight, but Alençon demanded that they attack.

With a shout the crossbowmen started forward. Until then the English had been lying down, but seeing the Genoese, they arose. The crossbowman halted, gave another shout, then resumed the advance. As they neared the English lines, they moved up the slope, unfortunately for them made slippery by the recent rain. They halted again, gave another cry, and fired their bolts.

Within the English position the order was given: “Draw!”

To rearm their crossbows, the Genoese had to place the tip on the ground and draw the string back. Their eyes were down on the task at hand. Behind the lines, Edward’s cannon began to belch iron balls toward the enemy.

“Loose!” came the command within the English longbowmen.

Unlike the cannon, the arrows made no sound. There was no warning to the Genoese until they heard the sound of arrows striking armor or the sickening “thud” as they pierced flesh, and the screams of the wounded and dying. Then in rapid succession a second volley was in the air and a third soon joined it. The Genoese were hit with perhaps 12,000 to 20,000 arrows a minute, far more than they could put into the air with their slower-to-load crossbows.

They had not wanted to fight this day. They soon discarded their heavy weapons and ran for the rear.

“The King has Commanded His Men to Kill Them”

When Alençon saw the crossbowmen in retreat, he flew into a rage. “Let us charge this rabble which fails when it is wanted.” With the handful of men-at-arms who had arrived, he led a charge through the Genoese, crying “Montjoye St Denis!” and hacking down the crossbowmen as they passed. Soon a combination of bodies and horses clogged the road the French used to advance.

Philip’s arrival on the battlefield did nothing to bring order to the French army. In fact, he himself flew into a rage when he saw the fleur-de-lis on Edward’s banner. As more French arrived on the battlefield, they attacked again.

King John of Bohemia asked where the fighting was. One of his knights replied, “Monsiegneur, it is in this way. All the Genoese have been defeated, and the King has commanded his men to kill them, and there is such confusion from their stumbling and falling amongst the horses that the road is blocked.”

The King of Bohemia had come to France to fight, and fight he would. Although he was handicapped by being half blind he was determined to get into the fray. “Then, my Lords,” he said, “you are my vassals and my friends and companions. I pray you take me somewhere where I can strike a blow.”

The knights cared for his honor and their reputations. Le Moine de Basele tied the bridle of his horse to the half-blind king’s horse. Another knight did the same on the other side. Their horses tied together, they advanced on the enemy.

Time after time—the sun all the while sinking lower—the French gathered as they arrived from the march and advanced up the slope to the English line. Philip joined in at least one charge, but his horse was killed by an arrow and he received a facial wound.

At one point the French broke through the wall of arrows. Because the longbowmen could fire at a rate of six to 10 per minute, they needed constant resupply. They could scavenge between the lines for spent arrows or they could await fresh arrows from wagons parked behind their lines. The French may have taken advantage of this situation to break through.

In any event, the French knights thundered past the spot where English arrows had previously stopped them. Beyond it, they were into the ranks of the dismounted men-at-arms and into a zone where the longbowmen could not fire for fear of hitting their own men.

At this time, in Prince Edward’s battle, Harcourt panicked. He sent Sir Thomas de Norwich to King Edward to ask for reinforcements. He then moved left behind the English lines to the battle on the left where he found the Earl of Arundel. He asked Arundel to attack the French flank. Arundel set off to comply.

Meanwhile, the French found the English dismounted men-at-arms as formidable as the archers. Sir Thierry de Senseilles penetrated the ranks of the English but in attempting to retire, the black horse Hainaut had loaned him stumbled and fell into a ditch. De Senseilles’ page found him pinned to the ground under the horse and pulled him free. This charge, like the others, failed.

Crécy was one of the few battles of the time during which the commander actually knew what was happening. From his vantage point in the windmill, Edward saw the French strike his son’s battle. By the time Norwich arrived, he had probably seen the attack by Arundel crush the French right.

Philip in Anguish at the Destruction of His Army

“Sir Thomas, is my son dead or thrown down, or wounded?” the king asked.

“No, Monsigneur, if it please God, but he is very hard pressed and would be very glad of your assistance.”

“Tell them they must permit the boy to win his spurs,” replied King Edward, “for I wish, if the day is won, that the honor should belong to him and to those in whose charge I have placed him.”

The sun set, but still the French sent charges up the rise. They may have charged as many as 15 times, well beyond sunset. Philip was in anguish at the destruction of his army by such a small group of English. He asked Hainaut what he should do. Hainaut answered that there was no option but to withdraw to seek safety.

The king made no answer at that time. He moved closer to the front line to support his brother, the Count of Alençon, whose banners he could see on a slight rise of ground, but the crush of archers and men-at-arms was so great he could not pass through. Darkness and fatigue were ending the long struggle.

The Battle of Crécy decimated the French nobility. An English knight, familiar with French heraldry, told Godfrey of Harcourt he had seen the Count of Harcourt’s banner, gold bars against a crimson field, on another part of the field. Godfrey crossed the battlefield in search of his brother, but when he arrived Jean was dead, as was his son. The French Counts of Alençon and Flanders died with many of their retainers. Also dead were both of Philip’s marshals and Guy, Sieur de la Tremoille (although the sources are unclear if the English captured the Oriflamme). Likely 1,500 French knights and squires perished at Crécy.

Count John of Hainault finally grabbed the bridle of Philip’s horse. “Sire, it is time to go away; you have lost this time, but you may win another time, and by staying longer you will lose everything.” He dragged Philip from the battlefield almost by force. A thick fog set in, and the English lit a large number of fires, the better to spot any more charges by the enemy.

The Glory of Victory and Shame of Defeat

Edward came down to the front lines and embraced his son. “My good son, Heaven grant you may persevere as you have begun: you have acquitted yourself nobly by the way you held your ground.”

The next morning Edward sent 500 men-at-arms and 2,000 archers to search for the French. They came across French foot soldiers from Rouen and Veauvais marching to join Philip, fought them, and then claimed to have killed 7,000.

Also in the morning, his men brought Prince Edward the caparisons (horse ornaments) of the King of Bohemia. He had died in front of Edward’s position with de Basele and others of his retinue. The horses lay dead, still tied together at the bridle. The King of Bohemia’s symbol was three ostrich feathers and his motto “Ich diem.” Edward adopted these as the symbol and motto of the Prince of Wales.

Edward selected two knights familiar with the hierarchy of French chivalry. With three heralds to keep records, they moved about the battlefield, identifying the fallen by their coats-of-arms.

Edward had won previous battles without gaining any strategic benefit, and Crécy would prove to be no different. He marched for the coast where he laid siege to Calais. The coastal city held out for months, allowing Philip to withdraw Prince John’s force from the south. Calais eventually fell and became an English stronghold in France. But this was not sufficient to save Edward’s lands in France … or to preclude another hundred years of war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments