By Michael D. Hull

Short, wiry, and with baleful blue eyes and an Old Testament beard, Maj. Gen. Orde Charles Wingate was unorthodox in thought and action.

His trademarks were a colonial-era pith helmet and a scruffy tropical uniform that he saved for special occasions.

Genius Or Mad Man?

To conventionally minded staff and command elements in the British Army, he was an out-of-control visionary whose ideas about guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines were unworkable. To others, he was plainly unstable. After all, while suffering from malaria and depression, he had tried to slit his throat with a sheath knife in his room at Cairo’s Continental Hotel on July 4, 1941.

But the eccentric Wingate was also a scholarly, brave, and innovative exponent of irregular warfare in the mystical, adventuring tradition of Colonel T.E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, and General Charles “Chinese” Gordon. And he had mentors in high places—Prime Minister Winston Churchill, General Archibald Wavell, and, eventually, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Allied Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Disruption Behind Enemy Lines

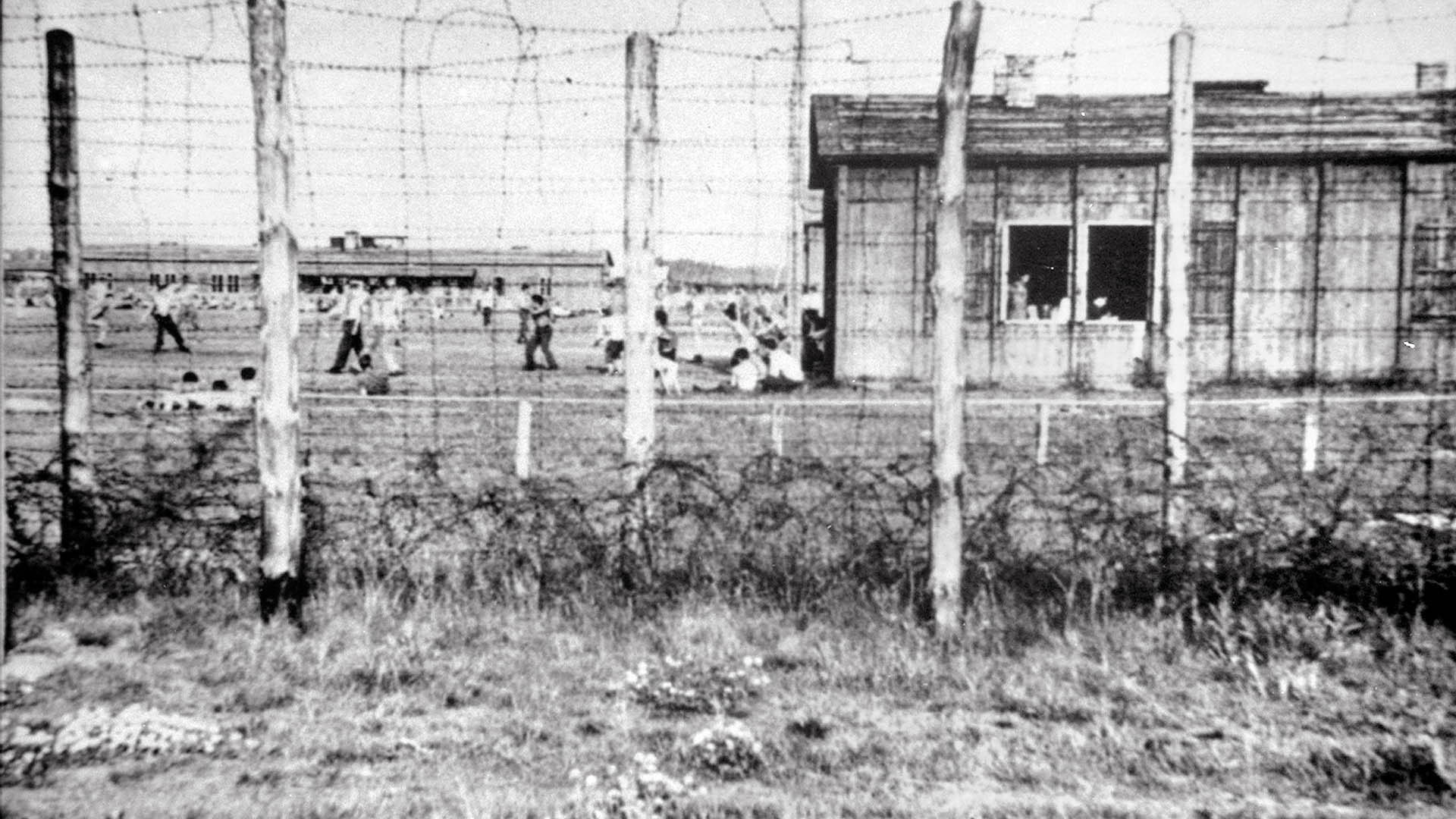

Wingate created, organized, and led the Chindits, named with an anglicized mispronunciation of the term for the statuary lions that guarded Burmese temples. The Chindits were a long-range penetration group designed to slip into Burma to maraud, ambush, and stir up trouble behind Japanese lines in World War II. Their primary mission was to support the British and Chinese efforts by disrupting enemy lines of communication.

Initially comprising battalions from the Burma Rifles, the Gurkhas, and the King’s Liverpool Regiment, the 3,000 Chindits used hit-and-run tactics and subsisted on air-dropped supplies. They harassed much stronger Japanese forces in the forbidding jungles of northern Burma.

From February to May 1943, the Chindits entered Burma from the west, crossed the Chindwin River, and fought effectively until reaching the Irrawaddy River. Crossing the Irrawaddy in an attempt to sever enemy links with the Salween River to the east, Wingate’s force found the terrain unfavorable and was compelled to return circuitously to India.

The Chindits became a legend, shoring up Allied morale and capturing the imagination of leaders like Churchill, though Wingate was criticized for diverting men and resources from conventional formations. The operations consumed men at an appalling rate. Only two-thirds of those participating in his first Chindit operation made it back to friendly lines. Of these, riddled with dysentery, typhus, and malaria, only a fraction were declared fit for further duty.

A Bored Youth Captivated By Tales Of Adventure

Born at Naini Tal, India, on February 26, 1903, into a military family, Orde Wingate was educated at Charterhouse School in Surrey, England, and entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1921. He was bored by team sports and the structured curriculum, and his cadet career, like his days at Charterhouse, was undistinguished. He was commissioned in the Royal Artillery in 1923.

Wingate had a yearning to soldier in exotic locales, fired by the example of his eminent cousin, General Sir Reginald Wingate, who had served as sirdar (commander-in-chief) of the Egyptian Army, governor-general of the Sudan, and high commissioner for Egypt.

Quest By Camel To Find “Lost Oasis”

After taking an Arabic course at the School of Oriental Studies in London, young Orde was posted to the Sudan as a company commander in the Sudan Defence Force. While there, he joined a Royal Geographical Society camel expedition to locate the legendary “lost oasis” of Zerzura in the vast Libyan Desert. It was unsuccessful.

Wingate returned to England in 1935, married 18-year-old Lorna Paterson, and started preparing for the qualifying examination to the Staff College at Camberley, Surrey. When he passed, but failed to gain admission, Wingate made a characteristically bold move. He confronted the chief of the Imperial General Staff (Army chief of staff). The young officer secured a general-staff intelligence appointment in 1936 with the British forces attempting to keep order between the Arabs and Zionists in Palestine.

This was his first big break. Palestine changed Wingate’s way of thinking and provided an opportunity to advance into the arena of irregular operations and show what he could do. He met General Archibald Wavell, the Palestine commander, and Churchill, who would ensure that Wavell’s plans for Wingate were supported at all levels. Almost from his arrival, Wingate was won over to the Zionist cause.

Lawrence Of Arabia Serves As Inspiration

He believed that it was his destiny to lead some wronged and beleaguered people to victory, as Lawrence had done with the Arabs in 1916-1918.

Wavell had devised the concept of “motor guerrilla” and other irregular forces to suppress Arab hostilities, so he chartered Wingate to organize, train, and lead a force of special patrols. They were called the Special Night Squads, which would eventually form the nucleus of Jewish irregular operatives and the modern Israeli Army.

The squads repelled Arab raids on Jewish settlements and halted sabotage of the Mosul-Haifa oil pipeline. The successes won Wingate the Distinguished Service Order and a mention in dispatches, and he was hailed as another Lawrence. He submitted a paper on unconventional operations to military theorist Basil Liddell Hart who, in turn, passed it along to Churchill.

Churchill’s Special Ops Vision

During his first weeks as prime minister in 1940, Churchill envisioned a program of special operations, ranging from commando raids along the German-occupied coast of Europe to the highly successful Long-Range Desert Group in North Africa. Likewise, the British fostered a partisan revolt in Ethiopia to retake the capital, Addis Ababa, from the Italian invaders, and restore the exiled emperor, Haile Selassie.

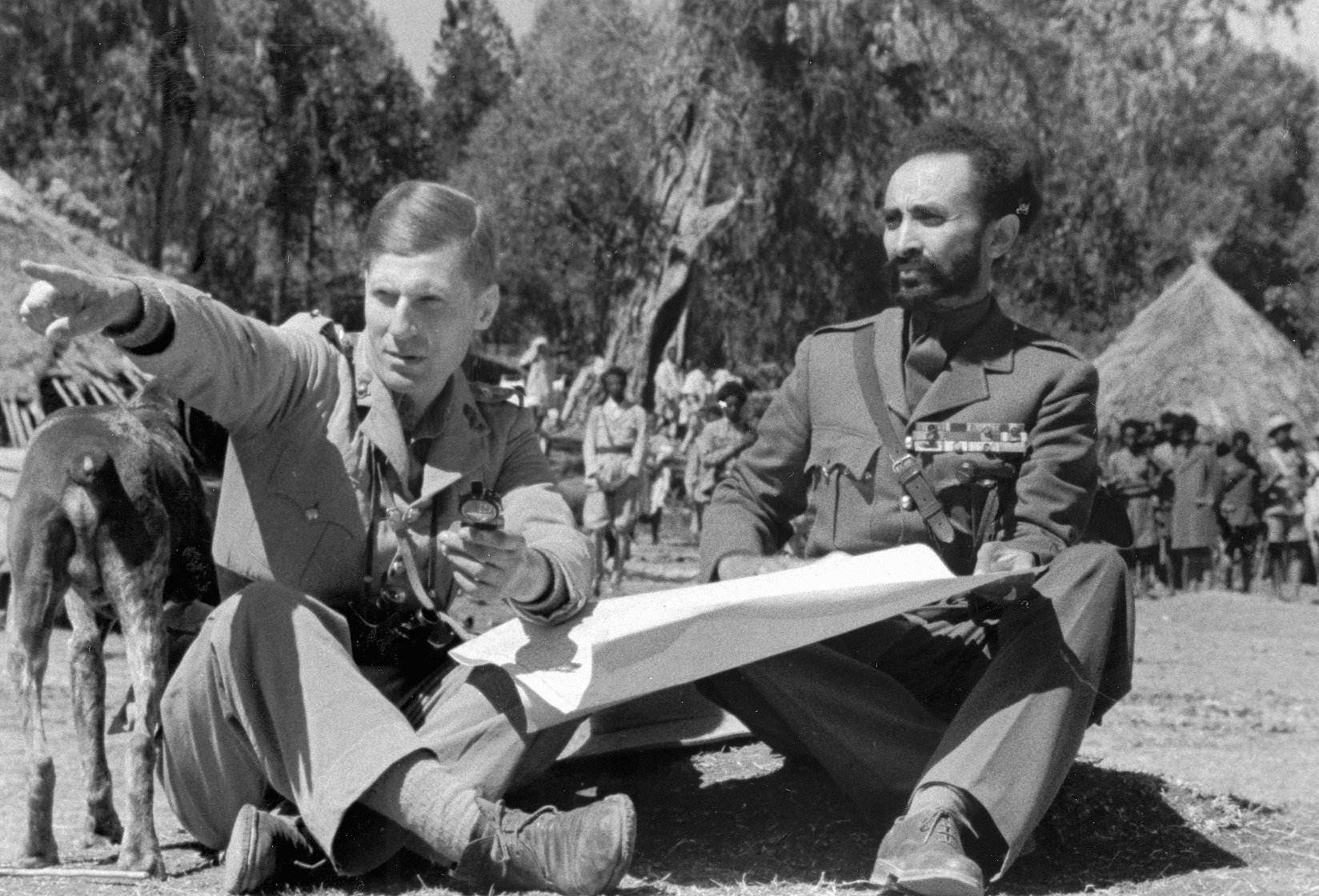

Wingate was appointed military adviser and the leader of the guerrilla campaign. A cadre of British officers and NCOs helped him train the native irregulars, and the campaign commenced in January 1941. Dramatic British successes in Libya helped, and Italian morale in Ethiopia dropped. With audacity and determination, Wingate’s Ethiopian and Sudanese tribesmen—named Gideon Force—disrupted the enemy garrisons and blocked the road to the capital.

British Guerrilla Force Triumphant

One by one, key Italian outposts were abandoned, and they fell back. Gideon Force opened the way for conventional British Army units to recapture Addis Ababa. The gallant emperor made a triumphant entry on May 5, 1941, and Wingate was awarded a bar to his DSO.

The triumph preceded the lowest point of Wingate’s life. He wrote a blistering report on organizational flaws that had hampered his Gideon Force and caused an upheaval at General Headquarters Middle East. Even his friend Wavell took Wingate to task for the intemperate tone of his paper. Then, after the failure of his thinly spread forces to smash the Afrika Korps, Wavell was reassigned as Viceroy of India.

On top of the strain of the Ethiopian campaign, malarial fevers pushed Wingate’s temperature up to 104 degrees. Rather than report to sick bay and be shunted off to convalescence in a rear area, he visited a private doctor. The result was that he greatly exceeded his prescribed doses of atabrine.

A Feverish Act Of Desperation

Alone and delirious in his Cairo hotel room, he stabbed himself in the throat. He was saved because he fell unconscious on the floor before he could finish the job. When help arrived, the bleeding was stopped before it was too late. Months of recuperation in England followed.

Meanwhile, after the fall of Singapore, Malaya, and the Philippines to the Japanese, the British created the Southeast Asia Command, with Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten in command. His deputy was the crusty old China hand, U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell.

In March 1942, with the temporary rank of colonel, Orde Wingate was on his way to war again. He was ordered by Wavell to report to the Bush Warfare School in India and take charge of guerrilla operations against the Japanese. After the fall of Rangoon and the disastrous British-Chinese retreat from Burma that May, Wingate carried out a detailed reconnaissance of Burma.

Wingate Prepares Chindits For Crucial Burmese Assault

An Allied hold on the country was vital because it was the world’s largest exporter of rice—and a geographic wedge between India and China.

Wingate spent the summer of 1942 training his Chindits, formally called the 77th Indian Brigade. The emphasis was on relentless forced marches, radio coordination, and the receipt of air-dropped supplies.

In February 1943, separate columns, supported by pack mules and even elephants, started slipping into enemy territory. During their first foray, the Chindits molested the Japanese all the way to the far side of the Irrawaddy, cut the Mandalay-Myitkyina railway line in several places, planted mines, and ambushed enemy units. When the Japanese pursued, Wingate’s columns disappeared into a new part of the jungle.

Guerrillas Emerge From Jungle Haggard Heroes

But the raiders’ luck and strength waned, and hunger, thirst, and disease forced Wingate to order a retreat back to India. Three months after starting out, and 800 men fewer, they returned to India. Emaciated, bearded, wearing his battered pith helmet, and lugging a rifle and map case, Wingate emerged from the jungle to find himself and his men heroes.

Churchill called Wingate “a man of genius and audacity and no mere question of seniority must obstruct the advance of real personalities to their proper stations in war.” The first Chindit campaign did much to break the spell of Japanese invincibility in the jungle.

Churchill wanted to make Wingate commander of the whole British offensive in Burma, but was dissuaded.

In August 1943, the prime minister took Wingate to the top-level Allied conference in Quebec, where the guerrilla leader presented a plan for an extended long-range penetration effort in Burma. He would vault his men over the enemy by transport plane and glider, and insert eight brigades to clear jungle air strips and set up a line of strongholds in the river valleys.

A Joint American And British Offensive

The strategy was a compromise between Churchill’s proposal for a thrust toward Singapore and an American plan for retaking Burma to secure land links with China. The briefing met with success. The Americans agreed to provide the air support, led by Colonel Philip Cochran, and to contribute a ground brigade, the 5307th Composite Unit led by Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill. “Merrill’s Marauders” would be trained by Wingate and his Chindits.

The second Chindit expedition jumped off in February 1944, as part of a three-pronged Allied offensive. In the north, Stilwell’s Chinese X Force thrust into Burma from India, covering engineers building a road and pipeline. In the south, Lt. Gen. William Slim’s British XV Corps pushed into Burma’s coastal area of Arakan, and the British IV Corps advanced across the Chindwin River. Wingate’s Special Force supported Stilwell and Slim by establishing air-supported bastions astride the key Japanese supply lines.

Enduring great hardships like their comrades in Merrill’s legendary force, the Chindits fought the enemy in a score of battles and far exceeded the agreed limit for time spent in the jungle. The hard fighting by all units—particularly in the epic British victories at Imphal and Kohima—paved the way for new Allied offensives and the annihilation of the Japanese field army in Burma.

“A Man Of Genius Who Might Have Become a Man Of Destiny

Wingate had become a living legend in the British Army, destined for greater roles, until fate stepped in cruelly on March 24, 1944. At the age of 41, and with the rank of major general, he was killed when the American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber in which he was riding crashed into the jungle behind enemy lines.

Churchill was shattered, as he had been when Lawrence was killed in 1935. He mourned the loss of “a man of genius who might have become a man of destiny.”

Although he was flawed at the “operational art” level (between strategy and tactics), and although he misjudged Japanese vulnerabilities to his 1944 plan, Orde Wingate was a brilliant planner, a clear thinker who could sway premiers and presidents, and a gallant soldier who could inspire men to risk their lives. No other special forces leader achieved the rank of general officer and led 20,000 men in the field behind enemy lines.

In Burma, Wingate expanded Allied capabilities. His ability to create and lead special forces in the field to achieve strategic ends has not been matched.

Suggested alternative title:

Orde Wingate And His Chindits Copied Guerrilla Warfare from Its Successful Use in the American Revolution and Elsewhere.