By Mason B. Webb

In German it was called Operation Rösselsprung, which translates to “Long Jump.” Its goal was to kill or kidnap the Allies’ “Big Three” leaders––Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill, and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt—when they met in Tehran, Iran, in November 1943. That the plan did not succeed is attributable to smart intelligence work, a drunken disclosure, and a bit of good luck.

Perhaps no operation was more audacious or had greater consequences to the war’s outcome if it had succeeded than Long Jump. Former Soviet Lieutenant General and KGB intelligence officer Vadim Kirpichenko said, “The first secret report that this act was being planned came from Soviet intelligence officer Nikolai Kuznetsov, who learnt about it during a conversation with SS-Sturmbannführer Ulrich von Ortel. Ortel was the chief of the sabotage group in Copenhagen, which was preparing the operation. While drunk, the senior German counterintelligence officer blurted out that preparations were underway to assassinate the Big Three. Later the Soviet Union and Britain discovered other facts confirming that preparations had been made to assassinate Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt.”

Soviet Counterintelligence in Iran

The assassination was scheduled to take place in Tehran, the capital of Iran, after the three Allied leaders announced plans to meet there to hammer out the final strategy for the war against Nazi Germany and its Axis allies. Stalin, whose nation was then still bearing the brunt of the German onslaught, also wanted to know how and when Britain and the United States would open a second front in Western Europe (Churchill was still dead set against a direct assault on the continent, fearing it would lead to catastrophe). The momentous meeting, dubbed Eureka, would be held at the Soviet embassy in Tehran between November 28 and December 1, 1943.

Iran was occupied by Soviet and British troops during the war and it was the “southern route” for Lend-Lease materials being shipped from the United States to the USSR. Although Iran had declared itself neutral on September 4, 1939, and despite the presence of Allied troops in the country, it continued to pursue an openly pro-German policy.

“The USSR paid close attention to intelligence in Iran,” said Kirpichenko, “and not only because the country played a major role in the Middle East during World War II. Its territory was used [by the Germans] for espionage and subversive activities against the USSR, and for disrupting activities in the most important regions of the Soviet homeland.”

In Tehran, the occupation armies maintained tight security, establishing numerous checkpoints at which pedestrians and vehicle drivers and passengers were required to show documents. The heavily guarded Soviet and British embassies were adjacent to each other inside a walled park in the center of town; the American embassy was a mile away.

With a German spy network firmly established in Tehran (there were an estimated 400 German agents in the city), the Soviets countered by beefing up their own intelligence operations there. The Soviet Foreign Intelligence Service in Iran was established, headed by Ivan Agayants. Its main mission was to expose foreign spies and organizations that were hostile toward the USSR’s interests and to prevent possible acts of subversion and/or sabotage aimed at Soviet military and economic interests in Iran.

Kirpichenko noted, “Soviet and British intelligence officers knew the real situation in that country, which helped them to frustrate Nazi plans in due time, including those to assassinate the leaders of the three great powers.”

Otto Skorzeny: Nazi Germany’s Legendary Commando

Chosen to plan and carry out Operation Long Jump was none other than SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) Otto Skorzeny, Germany’s mastermind of daring, unconventional, and audacious commando operations. The tall (6 feet, 3 inches), imposing Skorzeny was already famous (or infamous, from the Allies’ point of view) for his bold rescue of deposed Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in September 1943.

On July 25, 1943, Italy’s Fascist Grand Council, reeling from the invasion of Sicily and fearing a subsequent destructive invasion of the mainland, forced Mussolini to resign. He was then taken into custody.

Upon hearing this news, Hitler was determined to arrest those responsible for Mussolini’s ouster, including the king, and return Il Duce to power by force of arms. Additional German divisions were ordered to move immediately from France and the Eastern Front to Italy. But King Victor Emmanuel III moved faster and named Marshal Pietro Badoglio the new head of government. Badoglio declared Italy officially neutral while, at the same time, he began working secretly to effect an armistice with the Allies. Although Hitler had long ago eclipsed Mussolini as a powerful leader to be feared, he still felt it important to come to the aid of his fellow Axis partner.

During the rescue-planning phase, the names of six German special agents were presented to Hitler as the possible leader of such an expedition. One name that stood out was that of Otto Skorzeny, and Hitler personally selected him to rescue Mussolini.

From SS to Commando

Otto Skorzeny was born into a middle-class family in Vienna, Austria, on June 12, 1908. While attending the University of Vienna as an engineering student, he joined the fencing team and obtained the prominent dueling scar on his cheek (known in German as a Schmiss, for smite or hit) which was then a coveted mark of bravery among German and Austrian youth.

In 1931, as Nazism was gaining popularity in Europe, Skorzeny joined the Austrian Nazi Party and soon became a member of the paramilitary SA, or Sturmabteilung, while working as a civil engineer.

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Skorzeny volunteered for service in the German Air Force but was rejected because of his age (he was 31). He then joined the SS and was accepted into the Leibstandarte, Hitler’s bodyguard regiment, as an officer-cadet.

In 1940, when Skorzeny was an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) in the Waffen-SS, his engineering skills gained notice when he designed ramps to load tanks onto ships. He also proved his courage under fire during combat in Holland, France, and the Balkans, where he was decorated after capturing a large Yugoslav force, after which he was promoted to Obersturmführer (first lieutenant).

Skorzeny next saw combat with the 2nd SS Panzer Division (“Das Reich”) during the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. During the siege of Moscow that autumn, he was in charge of a “technical section” whose mission was to seize important Communist Party buildings, including the NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) headquarters, the Central Telegraph Office, and other high-priority facilities before the Soviets could destroy them. But when German forces failed to capture Moscow, the mission was canceled.

In December 1942, Skorzeny, now a captain, was struck in the head by shrapnel from a Russian rocket. At first refusing medical treatment, he was evacuated to the rear, awarded the Iron Cross for bravery, and sent home to Vienna to recuperate. While there, he became intrigued by commando operations and read all the published literature he could find on the subject. He then began to submit his ideas on unconventional warfare to higher headquarters, which took an interest in his thoughts.

His concepts soon reached the desk of Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the new head of the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (or RSHA, the Reich Security Main Office, which was composed of both the Security Police––Sicherheitspolizei, or Sipo––and the SD), who had replaced former head Reinhard Heydrich when the latter was assassinated in Czechoslovakia in June 1942. Skorzeny’s ideas were then passed on to SS-Brigadeführer Walter Schellenberg, head of Amt VI, Ausland-SD (the SS foreign intelligence service office of the RSHA), who requested a meeting with Skorzeny. So impressed was Schellenberg with the officer and his ideas that he appointed Skorzeny commander of the newly created Waffen Sonderverband z.b.V. Friedenthal. Skorzeny’s role was to train operatives in espionage, sabotage operations, and paramilitary techniques.

In the summer of 1943, Operation François became Sonderverband z.b.V. Friedenthal’s first mission. The objective was to make contact with dissident mountain tribes in Iran and encourage them to sabotage Allied supply lines through Iran heading to the Soviet Union. He discovered that the rebel tribes weren’t all that eager to help the Germans, and the mission was abandoned.

Operation Oak: The Daring Rescue of Mussolini

Although Skorzeny had not yet scored any major triumphs, Hitler decided to take a chance on him for Unternehmen Eiche, or Operation Oak, the rescue of Mussolini. After Mussolini’s arrest, Il Duce’s captors had moved him to the area of Pratica di Mare, an airbase southwest of Rome, where German agents soon located him. On July 27, 1943, Skorzeny and a team of commandos were flying in to parachute onto the airbase and free him, but the Junkers Ju-52 in which they were riding was shot down; Skorzeny and his men were barely able to parachute to safety and escape.

While new plans for a rescue were being made, Operation Avalanche put British and American forces ashore in southern Italy on September 3.

The ex-dictator was continually moved from one hiding place to another, but the Germans soon discovered him at a villa on La Maddalena, near Sardinia. Skorzeny was able to smuggle an Italian-speaking commando onto the island who confirmed that Mussolini was indeed there. Skorzeny then flew over in a Heinkel He-111 to take aerial photos of the location. The bomber was shot down by Allied fighters and crashed into the sea, but Skorzeny and his men were rescued by an Italian warship.

Mussolini was again moved, this time to the Campo Imperatore Hotel at the top of the Gran Sasso peak in the rugged Italian Apennine mountains in central Italy east of Rome––a place accessible only by cable car from the valley far below.

Captain Skorzeny flew over the site and photographed the area; it was formidable in the extreme, but he, Luftwaffe General Kurt Student (who had earlier conceived Germany’s famous airborne and glider operations against Belgium’s Eban Emael fortress and the British-held island of Crete), and Major Otto-Harald Mors, a paratrooper battalion commander, came up with a workable plan. Skorzeny assembled a team of 107 commandos who would be landed in gliders.

On September 12, 1943, Skorzeny and his 107 men silently descended on the mountaintop in 12 gliders, took the Italian Carabinieri guards by surprise without firing a single shot, and whisked the ex-dictator away in a Storch airplane to Rome. The rest of the commando team escaped by cable car. Skorzeny then flew Mussolini to meet with Hitler. It was a stunningly brazen, textbook example of the perfect commando operation––an operation that earned Skorzeny fame, promotion to major, Hitler’s gratitude (not to mention Mussolini’s), and the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross.

German Intelligence Learns of the Tehran Conference

In mid-October 1943, after the Germans broke a U.S. Navy coded message, German intelligence learned the date and place of the Tehran conference. Exactly who first came up with the idea of assassinating the Big Three during the conference is unknown (Kaltenbrunner can’t be ruled out), but the plan was approved by Hitler and Kaltenbrunner was told to carry it out. Because of Skorzeny’s recent rescue of Mussolini, he was the logical choice to head the mission.

On November 21, a German radio broadcast had announced that the Big Three would hold a meeting in Tehran at the end of the month, and there were rumors that the Germans might attempt to kill the leaders. As luck would have it, among a group of Soviet guerrillas operating in the Rovno forest in the German-occupied Ukraine was the legendary Soviet intelligence officer Nikolai Kuznetsov, who spoke perfect German. Posing as a Wehrmacht first lieutenant by the name of Paul Siebert, Kuznetsov penetrated German lines and became friendly with SS-Sturmbannführer Ulrich von Ortel, who happened to be well versed in the Long Jump plot.

Kuznetsov/Siebert kept pouring the drinks and the inebriated Ortel kept talking, telling Kuznetsov that he would soon depart for the meeting of the Big Three in Tehran, where, “We will eliminate Stalin and Churchill and turn the tide of the war! We will abduct Roosevelt to help our Führer to come to terms with America. We are flying in several groups. People are already being trained in a special school in Copenhagen.” Ortel even promised to introduce the spy to Skorzeny.

It was an intelligence coup of massive proportions.

The Soviets Thwart the Assassination Attempt

With Moscow and the Soviet legation in Tehran now alerted, the plan was allowed to unfold. The first German group, consisting of six radio operators, was dropped by parachute at Qum. Soviet intelligence officer Gevork Vartanyan said after the war, “Our group was the first to locate the Nazi landing party––six radio operators––near the town of Qum, 60 kilometers from Tehran. We followed them to Tehran, where the Nazi field station had readied a villa for their stay. They were traveling by camel and were loaded with weapons.”

Vartanyan noted that as the six men approached Tehran, a pre-arranged truck appeared and they loaded their equipment––radios, weapons, and explosives––into it. They moved into a “safe house” in Tehran, set up their communications equipment, changed into civilian clothes, and disguised their appearance by dyeing their hair. But then things started to fall apart.

“While we were watching the group,” said Vartanyan, “we established that they had contacted Berlin by radio and recorded their communications. When we decrypted these radio messages, we learned that the Germans were preparing to land a second group of subversives for a terrorist act––the assassination or abduction of the Big Three. The second group was supposed to be led by Skorzeny himself, who had already visited Tehran to study the situation on the spot. We had been following all his movements even then.”

Once Roosevelt and his party had arrived in Tehran, General Dmitry Arkadiev, head of the NKVD department of transportation, contacted Roosevelt’s chief of security, Mike Reilly, and told him of the plot. The American ambassador to the Soviet Union, Averell Harriman, then briefed the president on the still-sketchy details of the plot. All agreed that going ahead with the meeting was risky but that it should be done.

To reduce the danger to Roosevelt, who would have to travel by car the mile between the American embassy and the Soviet embassy, where the meetings would be held, it was decided to allow FDR and his party to stay in guest quarters at the Soviet embassy––where the hosts had already liberally planted secret listening devices to learn every word spoken by the president and his team.

Vartanyan said, “We arrested all the members of the first group and forced them to make contact with enemy intelligence under our supervision. It was tempting to seize Skorzeny himself, but the Big Three had already arrived in Tehran and we could not afford the risk. We deliberately gave a radio operator an opportunity to report the failure of the mission, and the Germans decided against sending the main group under Skorzeny to Tehran. In this way, the success of our group in locating the Nazi advance party and our subsequent actions thwarted an attempt to assassinate the Big Three.”

(In the interest of full disclosure, it should be noted that, to this day, counterstories have appeared that have claimed there never was a Nazi plot to kill or kidnap the Big Three in Tehran. Some historians contend that the “plot” was an imaginary one hatched by Stalin himself as a way to get Roosevelt to stay in the “bugged” guest quarters on the grounds of the Soviet embassy. Others who were high-ranking officers in Soviet intelligence at the time swear the plot was real and have written books on the subject. As with many aspects of the labyrinthine former Soviet Union, the true facts may never be known.)

Skorzeny’s Last Commando Operations

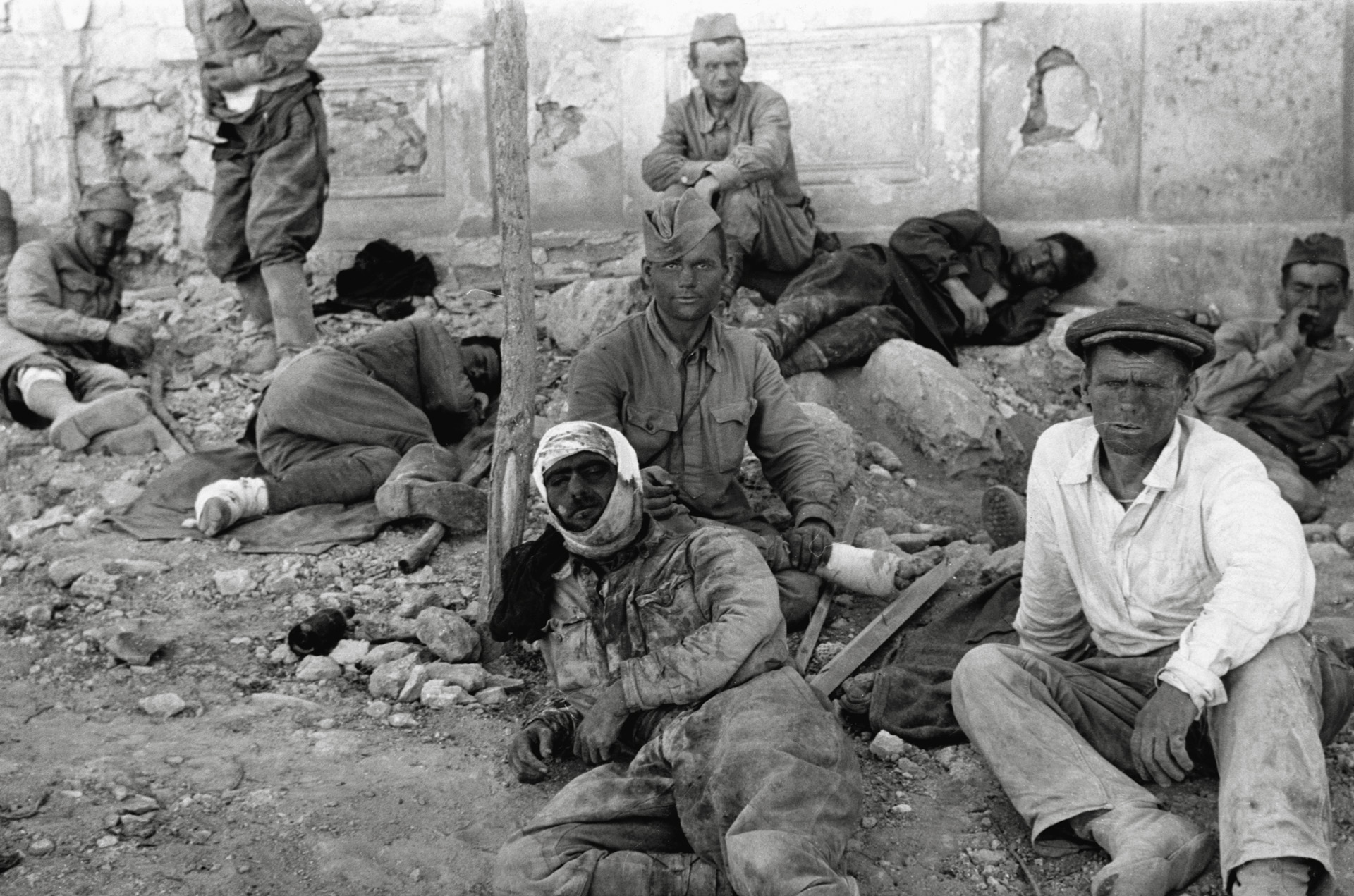

The failure of Operation Long Jump did not diminish Skorzeny’s reputation in the eyes of the Nazi warlords, nor put an end to covert commando operations. In the spring of 1944, his unit, now renamed SS Jagdverbände 502, undertook a mission to abduct the Yugoslav partisan leader Josip Broz Tito, but the operation was compromised and called off.

In mid-October 1944, Skorzeny was given a new assignment: Operation Panzerfaust (also known as Operation Mickey Mouse)––the kidnapping of Miklós Horthy, Jr., the youngest son of Admiral Miklós Horthy, Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary, who had earlier supported the Nazis but had become disenchanted with them and announced his intention to withdraw his nation from the Axis. Germany threatened to kill the younger Horthy if his father did not resign as regent. He did so and was placed under house arrest in Bavaria; his son was imprisoned at the Dachau concentration camp until the end of the war.

Skorzeny is probably best known in the West for, in December 1944, employing about two dozen English-speaking Germans in American uniforms and driving American vehicles to penetrate American lines in an operation called Greif (“Griffin”) that spread panic and confusion during the Battle of the Bulge. At war’s end, Skorzeny was involved in Germany’s Werwölfe (Werewolf) insurgency movement. He surrendered to the Americans on May 16, 1945, near Salzburg, Austria.

After the war, Skorzeny was charged by the Dachau Military Tribunal with breaching the 1907 Hague Convention in connection with his men masquerading as Americans during Operation Greif. He was, however, acquitted by the tribunal when it was learned that Allied teams sometimes did the same things. He fled from a detention compound in 1948 and, with help of a network of friends and former SS officers, changed his identity and moved relatively freely throughout Europe, eventually ending up in Spain, where he wrote a book about his exploits.

A heavy smoker, Skorzeny died of lung cancer in July 1975, his legacy as a brilliant, unorthodox commander, tactician, and theorist tarnished by the evil regime for which he worked.

But one wonders––had Operation Long Jump been successfully carried out, what would have been the consequences for world history? It remains another of the war’s many imponderables.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments