By James Allan Evans

It was a sorry tale. A brilliant general, military hero, and faithful servant of the state, blind and reduced to penury in his old age, sitting on the main street of Constantinople begging for his living. “Give an obol to Belisarius,” he repeated over and over again. A few passersby took pity and gave.

The legend told of the downfall of a great soldier and the ingratitude of his master, the Emperor Justinian, who held the throne of Byzantium from 527 to 565, and “An obol for Belisarius!” became a catchphase for the shabby treatment governments meted out to their ex-soldiers.

How the story arose we do not know, but sometime in the 14th century an anonymous author composed a long poem about it: the Romance of Belisarius. It tells how Justinian blinded Belisarius in his old age, confiscated his wealth, and left him to beg on the street corner. The tale is quite untrue: Belisarius died in his bed, only a few months before Justinian. But it is the last curtain call of a military officer whose exploits gave the reign of Justinian much of its luster.

Famous field marshals have always appreciated the power of public relations. Julius Caesar described his military campaigns in his Commentaries, which were supposedly rough drafts for a proper historical work. Napoleon spent his last years on St. Helena rewriting history with such success that he made himself a tragic legend. Belisarius was luckier than either of them: On his staff he had the foremost historian of his age, Procopius, who came from Caesarea in Palestine and became his legal adviser and secretary in 527. Procopius wrote—in seven volumes—a polished history of the wars that the Byzantines fought in Justinian’s reign up to 550 and then, some years later, he added another book taking the wars up to 552, the year when the Byzantines finally wiped out the Ostrogoths in Italy.

But by then, Procopius was a disillusioned man. He gave vent to his bitterness in an essay he must have written in the year that the first seven books of his great history appeared in the bookstalls of Constantinople. He did not dare publish it, but it survived, and a copy turned up in the Vatican Library in the early 17th century. Its popular name is the Secret History and it portrays the private Belisarius: a unattractive figure, weak, unreliable, and dominated by his wife.

Belisarius attracted Justinian’s attention before he became emperor, while his uncle, Justin I, was on the throne. Justin was an old soldier, almost illiterate, who became emperor unexpectedly in 518, and Justinian was his sister’s son, whom he adopted because he had no children of his own. Belisarius was a trooper in Justinian’s bodyguard when he was assigned to a command on the eastern front where war with the Persians had been dragging on since 525. Why Justinian picked Belisarius is hard to fathom, except that Belisarius was a handsome, dashing trooper and, more important, he had married a close friend of the Empress Theodora. Theodora and Antonina, Belisarius’s wife, both came from the demi-monde of the theater, which was beyond the pale in Constantinople. Even the church would not give the sacraments to the theater crowd. Yet both women rose to positions of power and wealth in the Byzantine Empire. It was probably a nudge from Theodora that brought Belisarius to Justinian’s attention.

So the man’s career blossomed. In 530 Belisarius defeated the Persians outside the fortress of Dara on the frontier. A Persian army of some 70,000 men, including the elite corps called the Immortals, advanced on Dara, led by Peroz, a scion of the Mihran family that traditionally provided Persia with its commanders. Belisarius probably had about 25,000 troops and shared command with the “Master of Offices,” a powerful official in the Byzantine bureaucracy named Hermogenes. But he made careful preparations for the Persian attack. He ordered trenches dug outside the south watergate of Dara, which directly faced the Persian advance, and behind the trenches he posted his infantry who were the least reliable troops in his army.

Behind the infantry Belisarius and Hermogenes took up their own posts, surrounded by their elite bodyguards, ready to intervene wherever they were needed. On the other side of the ditch Belisarius posted his crack cavalry corps made up of Huns, all skillful bowmen. The Huns, who had terrified the empire almost a century earlier when they invaded under their khan Attila, had now become valuable recruits into the Byzantine army, and Belisarius posted them where they could ride to the aid of his cavalry on his wings. Behind a little hillock where the Persians could not see them was posted a contingent of Heruls, barbarians who had sacked Athens in 267 but since then had settled within the Empire. They were the best corps of horsemen in his army.

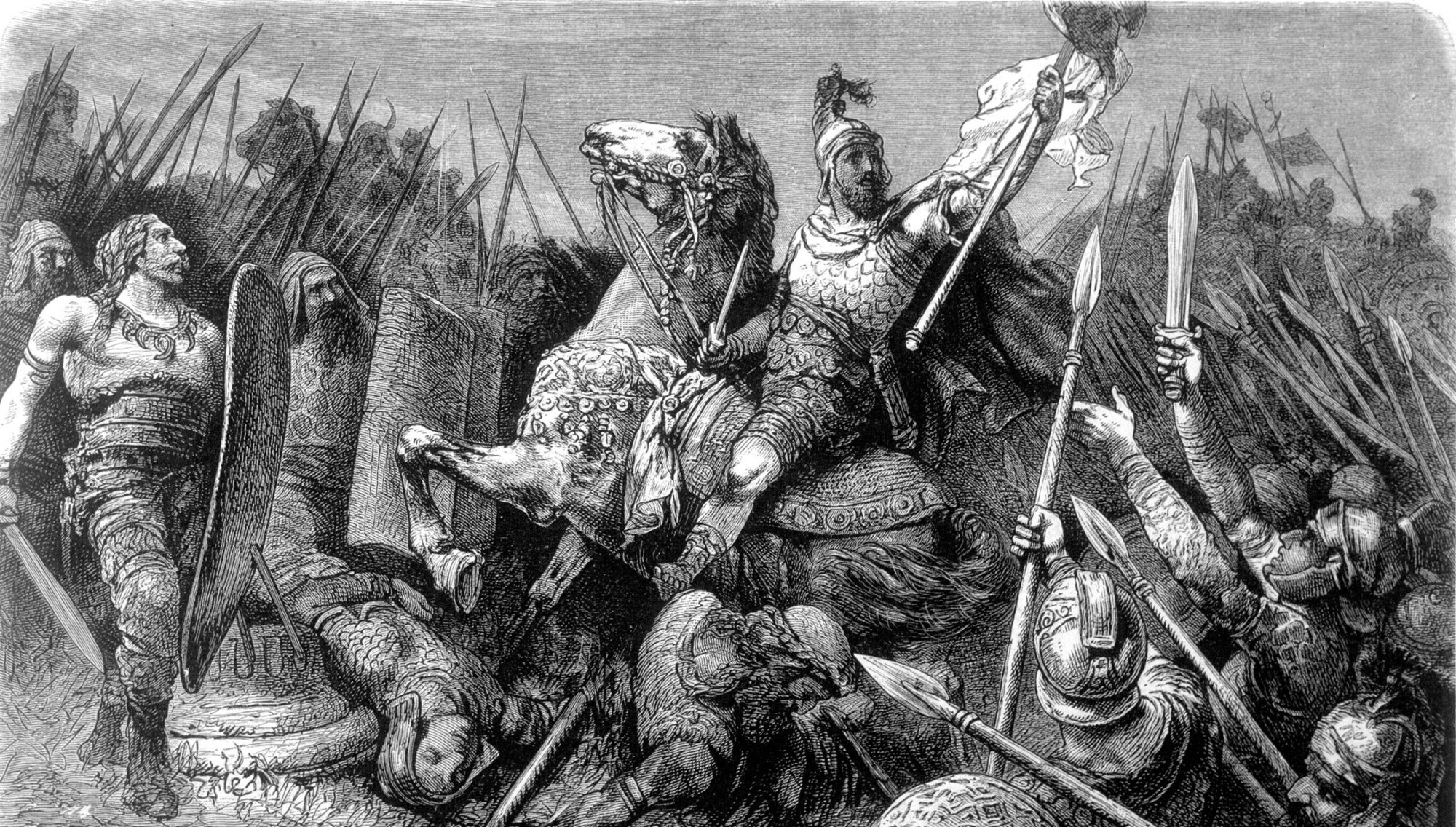

The Persians first hit the Byzantine left wing hard and forced it back, but the Huns rode to the rescue and the Heruls emerged from behind their hillock and assailed the Persian attackers from the rear. Then Peroz threw in his elite Immortals against the Byzantine right wing, but Belisarius moved some of his own guardsmen to strengthen it and, once again, the Huns rode to the rescue. The Persians were forced back in disorder, and their retreat became a rout. Their casualties were heavy. The Battle of Dara was the first victory over the Persians on the eastern frontier in over a century. Outnumbered, Belisarius had prevailed; the battle made his reputation.

The next year, he nearly lost it. The Persians, accompanied by their Arab allies from the Lakmid tribe, made a thrust across Syria toward Antioch. Belisarius countered and pursued them back as far as the Euphrates River. Belisarius, always cautious, would have let them cross the river and return home, but his troops taunted him with cowardice and, against his better judgment, Belisarius invited a battle. He drew his battle line at right angles to the river. Faithful Procopius, who wrote a report of what happened that exculpated Belisarius, tells that what defeated the Byzantines was the collapse of their right wing when their own Arab allies—led by the sheikh of the Ghassanid tribe al-Harith—turned and fled. Belisarius himself dismounted and fought shoulder to shoulder with his troops, thus stemming the rout. But it seems the official report told a much less flattering story, and Belisarius was recalled to Constantinople.

Justinian did not discard his officers easily, however, and Belisarius had a wife who was a friend of the empress. Fortune intervened. In January 532, Justinian almost lost his throne when a Constantinople mob rioted. It was a close call. The emperor had no reliable troops at hand, and if it were not for Belisarius and his loyal bodyguard and another general, Mundo, who commanded a corps of Heruls, his reign would have come to an abrupt end. Belisarius and Mundo put down the insurrection by massacring the mob while it was packed into the Hippodrome.

Thus Belisarius’s career was back on track. In 533, Justinian launched a campaign to conquer the kingdom that the Vandal invaders under King Geiseric had established in the Roman provinces of North Africa a century before. The Vandals had been fearsome enemies under Geiseric, who had even sacked Rome; among the loot they carried off to Carthage were treasures taken to Rome from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, which the Romans had destroyed in ad 70. Belisarius’s invasion force was modest: some 15,000 troops. But the Byzantines managed to prevent any word of their expedition from reaching the Vandal king, who was taken entirely by surprise. Unaware of his danger, he had dispatched a force to Sardinia to suppress a revolt there. Belisarius made a landing unopposed and advanced on the Vandal capital of Carthage, ordering his troops to do no looting, for he wanted the general population to look on him as their savior from Vandal tyranny.

The Vandal King Gelimer reacted swiftly once word of the landing reached him, and he launched a three-pronged attack on Belisarius’s little force that should have destroyed it if everything had gone according to plan. The battle took place at the Tenth Milestone outside Carthage. The Vandal attack, however, required coordinated timing, and one spearhead moved too soon. Gelimer’s brother was killed in the first skirmish, and when Gelimer came upon his body on the battlefield, he was so overcome by grief that he forgot to be a commanding officer. The Vandals fled in disorder. Even so, Belisarius did not enter Carthage on the day of battle, but waited until the next day, to avoid any possible ambush. Yet he and his officers were in time to enjoy a meal that had been prepared in the royal palace for Gelimer the day before. It was another great triumph.

There had to be one more pitched battle before the Vandal kingdom was destroyed, but the next year Belisarius returned to Constantinople with his royal captive, Gelimer, and the loot from Carthage, including the treasures from the Jewish Temple. Centuries earlier, when generals returned to Rome after having conquered Rome’s enemies, they would be granted a triumph: The victorious general would parade his captives and his plunder through the streets of Rome, along the “Sacred Way” through the Roman Forum, and he himself would bring up the rear in his chariot. When he reached the temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill he would lay down his command.

After the Roman Republic was overthrown and Rome was ruled by emperors, triumphs were reserved for members of the imperial family. But for Belisarius, Justinian restored the ancient ceremonial for a last time. Byzantium was a Christian empire, of course, and the pagan republican overtones of the ancient Roman triumphs were deleted. Belisarius walked on foot from his house to the Hippodrome where he prostrated himself before the emperor and the empress. But his loot and his captives were paraded publicly, and the Jewish community was greatly moved to see the seven-branched candlestick and the other treasures from its temple now reappearing after almost five centuries. A Jewish spokesman counseled Justinian to send the treasure back to Jerusalem, and he did. Once there, it was housed in various city churches.

Justinian was not above a little envy as he watched Belisarius playing the role of a great conqueror in public gatherings, but he had another mission for him—the recovery of Italy. No emperor had ruled in Italy since 476. The imperial palace in Rome stood empty. The emperors in their final years in Italy had moved to Ravenna, and now an Ostrogothic king, Theodahad, ruled there, having murdered the last direct descendant of the great Theodoric who had established the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy. Justinian took his measure and did not expect a great deal of resistance. He dispatched Belisarius to Sicily in 534 with an army only half the size of that he had led against the Vandals. Sicily fell easily. Only in Palermo did the Ostrogoths put up much of a fight, and it was easily overcome. The following year, Belisarius was ordered to cross over into Italy and advance against Rome.

All went well at first. Naples put up a fight, but the Byzantines got into the city at night through the main aqueduct. Then Rome fell without a blow. The Ostrogoths had dethroned Theodahad and replaced him with a better soldier named Vitigis, but he made the error of entrusting Rome to a small garrison and marching north to meet an invasion of the Franks. The pope urged the Romans to open the city gates to Belisarius, and as he marched in the Ostrogothic garrison fled. Once Vitigis realized he had made a tactical error, however, and Rome was in Byzantine hands, he returned hastily to recapture the city. His siege would last a year and nine days, ending in mid-March 538.

It was an epic siege, and it was the high point of Belisarius’s career. With only some 5,000 men, he outlasted Vitigis and his Goths. But once the siege was over, new troops arrived from Constantinople with commanders who challenged Belisarius’s cautious strategy, notably a eunuch from the court named Narses, still at the beginning of a brilliant military career and envious of the great Belisarius. In Constantinople, Justinian wanted the war concluded. The defenses in the Balkans needed attention, and in the east there was always Persia. Justinian was ready to give the Goths generous terms, which would have left them in control of Italy north of the Po River.

But Belisarius wanted another triumph and to capture Ravenna he descended to a little skullduggery. He agreed with the Gothic notables that if they surrendered Ravenna, he would declare himself independent of Constantinople, and henceforth the Goths and Italians would rule Italy with himself as emperor. Belisarius had no intention of rebelling against Justinian, but he played along with the plot. The Goths surrendered Ravenna. Belisarius accepted the surrender and then returned to Constantinople with his loot and Vitigis as his prisoner. The Goths discovered they had been tricked and could only grind their teeth.

Belisarius got a cool reception in Constantinople. Disasters plagued the Empire in 540. In the east, the shah of Persia, Khusru, broke the peace and launched an invasion, capturing and destroying the great city of Antioch. In the Balkans the Slavs made a foray, reaching the walls of Constantinople before they were turned back. Justinian probably had doubts about how permanent Belisarius’s conquest of the Goths in Italy would be, and if so, he was right: The Goths soon chose another king, Baduila, who proved to be a much more able leader that Vitigis had ever been. Justinian dispatched Belisarius to the eastern frontier to repair defenses there. But two years after Belisarius’s departure from Italy, catastrophe struck the Empire. There was a great epidemic of bubonic plague. The toll of dead was enormous.

Justinian himself fell ill, and during his illness some officers on the eastern front, including Belisarius, began to speculate about his successor. Not another emperor like Justinian, they said. But Justinian recovered, and when news of these seditious conversations reached the Empress Theodora, Belisarius was recalled, his property was confiscated, and he was denied contact with his friends.

But he was too valuable to lose. In 544 he was sent back to Italy and there, for four years, he fought a holding action against Baduila. No victory was possible. The plague made recruiting new troops desperately difficult, and other fronts needed reinforcements as much as Belisarius. The Ostrogothic war dragged on and all Italy was laid waste. In 548, Belisarius sent his wife Antonina back to Constantinople to beg Theodora to intervene on his behalf, but before Antonina arrived Theodora died of cancer. Then Antonina asked Justinian to recall her husband from the hopeless conflict; the great general’s career was over. In 552 the Byzantines would defeat the Ostrogoths at last, but the victorious general would be Narses, who had persuaded Justinian to provide him with sufficient troops.

Belisarius remained a respected figure in Constantinople, and he had one last triumph. In 559 the Kutrigur Huns attacked, and Constantinople was in danger. Belisarius, now old and frail, went out with a scratch force made up of some of his veterans and peasants who had been driven from their farms by the Huns and laid an ambush. The Huns rode into it and were put to flight.

Then Justinian recalled Belisarius and once again he went into retirement. Shortly before his death he was suspected of involvement in a plot against Justinian, but the emperor never seriously thought that Belisarius was a traitor. However, on his death, Justinian confiscated his property, for Belisarius was enormously rich—like all Byzantine generals, Belisarius had used his conquests to fill his own pockets as well as the imperial treasury. On that level, he was a child of his times.

The Romance of Belisarius has it wrong. Belisarius never had to beg on the streets. Thanks to his secretary Procopius, we know him better than any other general of his time, and perhaps he was not the most brilliant of them. Probably that accolade belongs to Narses. But when historians study the age of Justinian, Belisarius will always appear as its military genius who defeated the Persians, the Vandals, and at the end of his life, the Kutrigurs, and failed to defeat the Ostrogoths only because his jealous emperor denied him support. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments