By John W. Osborn, Jr.

With the exception of the French Foreign Legion, the concept of the mercenary, or soldier of fortune, seemed extinct after World War II. It had a sudden resurgence, however, in the chaos of post-independence Africa. There, in a land like something out of a nightmare, an Irish-born small businessman from South Africa would make himself the best-known mercenary leader of his time. A decade later, in another tropical paradise, he would lead one of the most farcical coups ever attempted in military history. It’s all part of the legend of how Thomas Michael Hoare would become known in the history books as “Mad Mike” Hoare.

The Simba Revolt

The Belgian Congo had a long and sinister reputation, serving as the setting for Joseph Conrad’s great novel, Heart of Darkness. The mad Kurtz’s dying words, “The horror! The horror!” were grimly descriptive of the Congo, circa 1960-65. After governing the colony for 75 years, Belgium rushed the Congo to independence on six months’ notice, with the cynical expectation of continuing to run things behind the scenes. “BEFORE INDEPENDENCE = AFTER INDEPENDENCE,” the Belgian military commander wrote on a blackboard at an officers’ briefing. But the Congo instead disintegrated into chaos—army mutinies, riots, massacres, rape, pillage, and an attempted secession by its richest province, Katanga, which had to be suppressed by United Nations troops. “Anyone here been raped and speaks English?” a British Broadcasting reporter asked a group of refugee Belgian women at the time.

If possible, the worst was yet to come—the Simba (Lion) rebels. Although armed by China, Egypt, and Algeria, the Simbas were fundamentally too berserk to have anything approaching a coherent political ideology. Believing that their leader, Nicholas Olenga, had given them magical immunity against bullets, the rebels rampaged through the northern Congo, routing the uniformed rabble that called itself the Congolese National Army (ANC) and raising the already shocking level of atrocity to new, stomach-turning heights.

In a desperate effort to stem the Simba revolt, the leader of the Katanga secession, Moise Tshombe, was brought back from exile to become premier on June 30, 1964. (To appreciate just how bizarre such a turn of events was, even for the Congo, imagine Jefferson Davis being elected president of the United States because of the Custer debacle at the Little Bighorn.) Tshombe had introduced white mercenaries in Africa during his Katanga revolt, and he was ready to use them again to fight the Simbas. To command the mercenaries, Tshombe’s chief white military advisor, Jeremiah Puren, sent for a long-time friend from South Africa, “Mad Mike” Hoare.

Soldiers of Fortune

Although born in Ireland, Hoare had fought with the British Army in Burma during World War II. He then immigrated to South Africa, working as an accountant, used car dealer, and safari organizer. In July 1964, Hoare flew to Leopoldville, the Congolese capital, met Tshombe, and agreed to organize and lead a mercenary force for him. An advertisement in South African, Rhodesian, and European newspapers offering “employment with a difference” brought 500 eager volunteers rushing to the Congo.

In time, 19 different nationalities would be represented in Hoare’s mercenary force, called 5 Commando, although the majority of the men were South Africans and Rhodesians. (The one American in the group defied the State Department prohibition on enlistment by renouncing his citizenship.) Each man signed a contract, ludicrous under the circumstances with its legalistic verbiage, to serve a six-month tour for $420 a month, plus $12.50 each day in combat pay. The contract even provided for a carefully worked out percentage formula for physical disabilities—75 percent for a lost right arm, 60 percent for a left, moving down to 5 percent for a big toe and 3 percent for a small.

A journalist covering the Congo, David Reed, would write admiringly of Hoare’s men: “In another age, they would have found their calling on the Spanish Main. They would have fitted well into the ranks of the condottieri, the hired soldiers who fought in Renaissance Europe. And they would have done themselves proud as gunfighters in the American Wild West.” Two of Mike Hoare’s best British officers demonstrated the extreme character types attracted to the life of a mercenary-soldier of fortune. Jeremy Spencer was an upper-class adventurer, a product of Eton and the Coldstream Guards. Hoare regarded him so highly that when Spencer was killed in action, he named his just-born son after him. John Peters’ military past was murkier; he was either a veteran of the elite British Special Air Service or else merely a deserter. Hoare promoted him from sergeant to captain, while always considering him “mad as a snake.” The Yorkshire-born Peters proved as much by killing a Belgian fellow-mercenary in a knife fight over a cot.

Other military adventurers found their way into 5 Commando from previous service for different nations. Wehrmacht veteran turned bartender Siegfriend Mueller was a public relations embarrassment for Hoare, happily flaunting his World War II Iron Cross. Former cavalryman Maurice Lucien-Brun, who “spoke English like Charles Boyer” according to Hoare, sailed his 38-foot ketch from France to South Africa to sign up. Romanian Ferdinand Calistrat had served in Spain’s little-known, brutal version of the French Foreign Legion, the Spanish Foreign Legion, nicknamed aptly “the Bridegrooms of Death.” (Read about these and other lesser-known stories from military history inside the pages of Military Heritage magazine.)

A few of the mercenaries were politically motivated, mainly anti-Castro Cubans who saw the Congo as part of the ongoing struggle against Communism. And then there was the inevitable human flotsam—a man with terminal cancer using the Congo to “get it over with,” drunks, drug addicts, hardcore criminals out for loot, and sadists like the Danish soldier who enjoyed boiling Simba heads. One man became unhinged and fired on his own comrades until they shot him down. An enraged officer stood over the mortally wounded man, shouting, “I hope you die, you bastard, you!”

Mike Hoare whittled the initial 512 volunteers down to a more manageable 300 (another 150 later signed up), then put them through two months of punishing, British-style military training. As for fighting, Hoare told his officers that “since there is no book on the Congo, you will have to write it yourselves.” Hoare’s own chapter on tactics was basic, but devastatingly effective: wild, hell-for-leather jeep charges with mounted machine guns and automatic weapons blazing. The Simbas, quickly learning that they weren’t immune to bullets after all, would scatter at the first sign of 5 Commando.

As Hoare’s men moved north, liberating towns previously held by the Simba rebels, they also liberated money, gold, diamonds, ivory, and anything else of value. Some mercenaries made a point of carrying dynamite to blow open safes; a South African said he was there to steal enough to open a garage back home, and eventually did so. Not naïve about many of his men’s primary motivations, Hoare generally looked the other way. When he did enforce discipline, Hoare was blunt and brutal. A soccer player who raped and killed a Congolese girl was held down while Hoare shot off his big toes (presumably he did not get the 5 percent disability). On a later television appearance in Great Britain, an indignant British brigadier spluttered that Hoare’s methods were “orthopedically unjustifiable.” A Belgian who had already given Hoare trouble and been clubbed to the ground with the commander’s revolver butt, crossed the line by killing an eight-year-old Congolese boy. “This time,” Hoare said ominously, “I fixed him forever.”

Dragon Rouge

In their strongest challenge to the Congolese government, the Simbas captured the nation’s second-largest city, Stanleyville, in November 1964. There they set up a rump regime recognized by the Communist bloc, took over 1,000 white hostages, including 500 Belgians and 29 Americans, and sentenced American medical missionary Dr. Paul Carlson to death as an alleged spy. Washington and Brussels decided on a joint pre-dawn airborne drop of Belgian paratroopers, dubbed Dragon Rouge. At the same time, a ground force led by a Belgian colonel, composed of 5 Commando; a smaller, rival mercenary unit, 6 Commando; and ANC troops would rush into the city.

Hoare was told of the plan only three days before, after spending a month fighting his way 300 miles toward Stanleyville, and was given only an hour’s notice to make the last 144 miles overnight. The convoy started out at 5:30 pm on November 23, 1964, but was soon reduced to a 10-mile-an-hour crawl by rain, muddy roads, and repeated Simba ambushes. Mad Mike Hoare himself called the drive the “most terrifying and harrowing experience of my life.” He finally confronted the Belgian colonel and demanded a stop until daylight. The convoy halted at 3 am, 60 miles from Stanleyville.

By the time the convoy reached the city, Belgian paratroopers had successfully jumped from American C-130 transports and fought their way into the city. The Simbas soon fled, but not before murdering Dr. Carlson and 280 other hostages, including 28 Catholic priests and nuns. Although greeted as heroes, the mercenaries proceeded to loot Stanleyville; two South Africans blasted open a safe and disappeared with $65,000.

Hoare’s men spread through the area surrounding Stanleyville, rescuing hundreds of priests, nuns, and other European missionaries. The fall of Stanleyville did not end the Simba revolt. Egypt and Algeria continued to ship them arms, and the fighting dragged on for another year. Siegfried Mueller narrowly survived an ambush in which most of the 40 vehicles in his column were destroyed. From their improved tactics, Hoare rightly suspected the Simbas were getting outside help. A diary found on a Cuban killed fighting with the Simbas revealed that no less a personage than Ernesto “Che” Guevara was leading a team of foreign advisors.

By March 1965, Hoare had cleared the northeast Congo, closing the Simba’s supply lines from Sudan and Uganda. He then turned his attention to the rebels’ last bastion along the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. At the end of the rainy season, he launched a new offensive on September 25, 1965, attacking with five Commando units, two properly trained ANC battalions, PT boats, and four B-26 bombers piloted by his anti-Castro Cubans. After four days of pounding, the Communist Cubans either lost or abdicated control of the Simbas, who made a massed charge and were mowed down almost point-blank by Hoare’s men.

Mad Mike Hoare: A Warrior Without a War

Tanzania, on the far side of the lake, suddenly cut off its support for the Simbas, forcing Guevara and his men to flee. As journalist David Reed noted, Hoare and his mercenaries had “turned the tide in the Congo.” But with the Simbas finally crushed, the ANC commander, General Joseph Mobutu, felt free to oust Tshombe and dismiss Hoare. The murderous John Peters was put in charge of 5 Commando during its mostly garrison duty until being disbanded in May 1967.

For the next decade, the closest Mike Hoare came to mercenary activity was by serving as technical advisor for a movie about his African adventures, The Wild Geese, starring fellow wildmen Richard Burton and Richard Harris. While other mercenaries fought and died, Hoare’s attempts to involve himself in the Nigerian civil war, the Persian Gulf, Angola, and Mozambique were uniformly rebuffed—his notoriety had made him too politically hot to handle. When at last he saw action, it would be in the most idyllic of places, in the most comically chaotic of circumstances.

“Ye Ancient Order of Frothblowers”

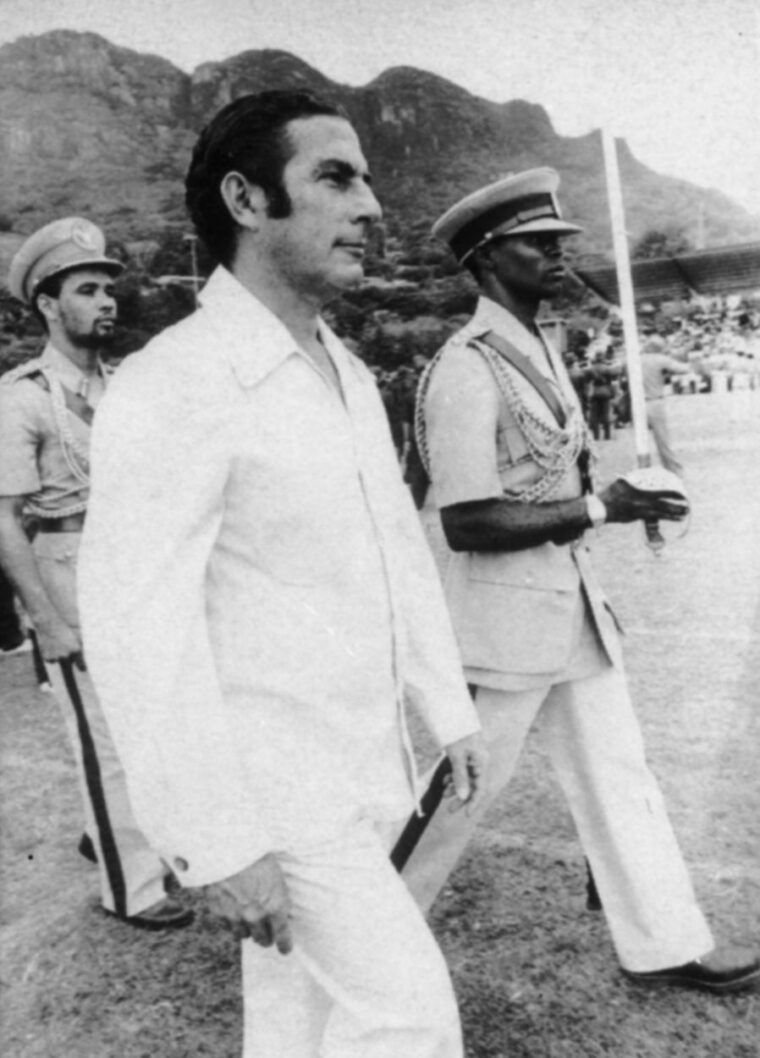

Hoare had visited the Seychelles—93 islands in the Indian Ocean, 700 miles off the east coast of Africa—in his pre-Congo days, and like many he was entranced by what he saw. “Dense mangrove trees on the edge of lovely white beaches, and surrounding it all crystal clear water,” he waxed poetically. “Sounds enchanting, doesn’t it? Well it is—a regular paradise.” The islanders were so easy-going that the British had to literally force independence on them in 1976. The next year, their playboy president, James “Jimmy” Mancham, had a romantic tryst in the Savoy Hotel in London interrupted by a phone call announcing that he had been overthrown by his leftist prime minister, Albert Rene. As grim as Mancham was amiable, Rene imposed one-party rule, built up the islands’ first standing army with help from radical Tanzania, and permitted an oversized Russian embassy to open for business there.

In May 1978, Mike Hoare was hired by a group of wealthy Seychelles exiles to overthrow Rene and restore Mancham. Two years of clandestine plotting ensued—shadowy meetings with exiles, a powerful Kenyan politician, and South African security and military intelligence, followed by two reconnaissance trips to the islands by Hoare, using an alias. Hoare’s final plan was to lead a force of mercenaries posing as members of a South African sports club on a boozing holiday to the Seychelles while Rene was gone. They would seize key points in the capital, Victoria, while Kenyan forces flew in to ostensibly restore order and, not incidentally, Mancham.

Hoare filled his team, paying the men $1,000 each, with old Congo hands, including Jeremiah Puren, former South African and Rhodesian special forces and intelligence operatives, and two ironic choices—an Italian actor from The Wild Geese, Tullio Moneta, and Sven Forsell, an Austrian former opera singer turned aspiring filmmaker who wanted to do a documentary about mercenaries. Calling themselves “Ye Ancient Order of Frothblowers,” Hoare and his 45 men flew into Victoria on November 25, 1980. Then, two years of careful plotting was undone by one moment of jaw-dropping stupidity.

The Last Adventure of “Mad Mike” Hoare, the Legendary Mercenary

If Kevin Beck had ever been in South African intelligence, as he claimed, he showed precious little of it that day. One of the last mercenaries off the plane, he had evidently been preparing for his role of hard-drinking sportsman during the flight. While Hoare and the others, in matching team blazers, slacks and tote bags with their automatic weapons stored safely inside, were waved through the “Nothing to Declare” section by unsuspecting Seychelles customs officers, Beck went into the “Something to Declare” line by mistake. When inspectors opened his bag and found his weapons, Beck blurted out, “I don’t know what it is, but there are 44 more of them in the bags outside.”

A customs inspector tore out of the building for help, while Hoare and his men armed themselves inside and seized hostages. In the bedlam, South African ex-paratrooper Johan Fritz was accidentally shot by another mercenary—the only fatality among Hoare’s men. The mercenaries were soon in a standoff with the rag-tag Seychelles army. Hoare was prepared to fight it out to the last, but his men lost their nerve. When an Air India Boeing 727 made a scheduled landing, the panicked mercenaries commandeered it, forcing Hoare on board with them, and flew back to South Africa. “They were so polite and gentlemanly that it just did not seem as if we were being hijacked,” a stewardess said later, in an appropriate finish to the day’s farcical events.

South Africa took a less tolerant view. Under intense international fire for the fiasco, the country tried and convicted Hoare of air hijacking and other charges and sentenced him, at age 63, to 20 years in prison (it was later reduced by half). He was released in 1985, still unrepentant, but his mercenary career was finished. He was now a relic of a bloody, bygone era, and Africans had learned to fight and kill each other well enough without needing whites to show them how. The scenes for mercenary action would soon shift to South America and the Balkans, and mercenaries increasingly would become corporate businessmen passing as bland security personnel. The romantic era of “Mad Mike” Hoare and his Wild Geese was gone forever.

Mike saved a lot of lives while he was in command during The Congo crisis, I can remember it very well as I was serving with Irish United Nations during that time. Regards Mick