By Pat McTaggart

Rostov was the key to the Caucasus and the rich Soviet oil fields that lay along the Black and Caspian Seas. No one could accuse Adolf Hitler of being underambitious. The great battles of encirclement at Kiev, Minsk, Uman, Smolensk, and other pockets had yielded hundreds of thousands of Russian prisoners during the first months of the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, otherwise known as Operation Barbarossa. Believing that Soviet Premier Josef Stalin was almost certainly finished, the German leader thought his armies were capable of even greater victories.

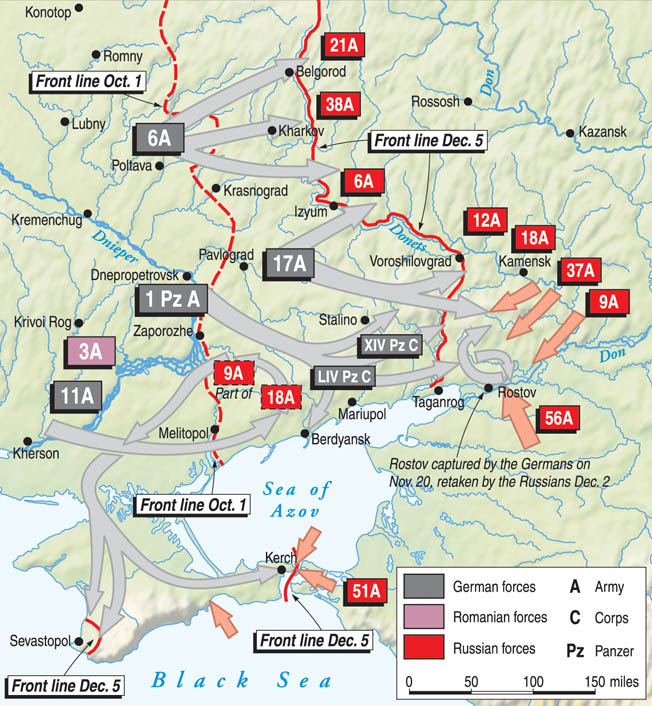

With that in mind, he ordered his eastern forces to continue attacking all across the vast front. In the north, Leningrad was the target. In the center it was Moscow, and in the south it was the Ukraine with its great agricultural and industrial resources. In conjunction with the capture of the Ukraine, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South was ordered to capture the Crimea and, at the same time, take the city of Rostov-on-Don and the bridges that spanned the mighty river on which it sat.

Rostov: An Old Trading City on the Don

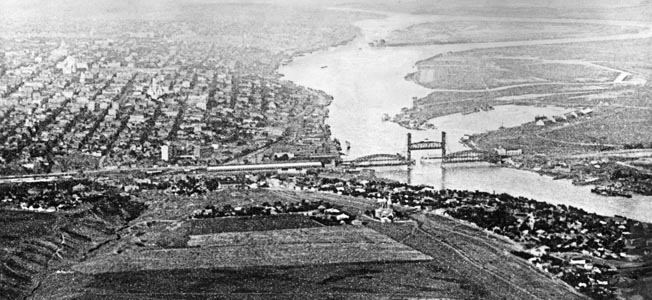

On December 15, 1749, a small customs house had been established near the mouth of the Don River to help control trade with the Turkish Empire. A fortress was soon built on the site, and gradually the small town that sprang up in the area turned into a city full of tradesmen and merchants.

At the beginning of Barbarossa, Rostov was more than 1,000 kilometers behind Army Group South’s staging areas in Poland. The people of the city watched as troops headed for the front passed through almost daily. Soviet propaganda assured civilians that the Germans were being slaughtered by the thousands and that the enemy would soon be vanquished. In reality, the forces of Army Group South were assembling less that 400 kilometers away, ready to continue their victorious advance.

Von Rundstedt had done his job well. Lt. Gen. Dmitrii Ivanovich Riabyshev’s South Front and Lt. Gen. Mikhail Pertrovich Kirponos’s Southwest Front had been shattered in the previous months. Kirponos had paid with his life on September 20 when he was killed while trying to escape German forces. His replacement was the extremely capable Marshal Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko.

Although the Germans had inflicted a grievous wound on the Soviet forces in southern Russia, it had come at a price. The seemingly endless steppe, sandy roads, and dust-filled air had taken their toll on men and machines. Engines were worn out, supply lines were long, and casualties had cut the strength of divisions. Replacements of both men and machines were slow in coming, and most of von Rundstedt’s panzer and motorized divisions could only field a half or less of their combat vehicles at a time. Nevertheless, Hitler insisted that his new priorities be met.

Breaking Through the Soviet’s Defenses

The main part of Army Group South began its redeployment in late September. Taking the Crimea would be the task of the 11th Army, while the 6th Army would advance toward Kharkov. The task of taking the Don Basin fell to the 17th Army, and the 1st Panzer Group would strike out toward the Sea of Azov with its eventual objective being Rostov.

General Ewald von Kleist’s 1st Panzer Group had two motorized corps (III and XIV) to use as his main attacking force. During the last week of September, German units moved into bridgeheads at Zaporozhe and Dnepropetrovsk in preparation for the forthcoming assault. Mechanics worked furiously trying to fix broken-down vehicles. The trickle of replacements coming from the West were assimilated into units as best they could, but the divisions going into battle would still be short of men and machines as the assault began.

General of Infantry Gustav von Wiethersheim’s XIV Army Corps (mot.) was deployed in the Dnepropetrovsk area facing the Soviet South Front’s 12th Army. To his north, General of Cavalry Eberhard von Mackensen’s III Army Corps (mot.) was facing the Southwest Front’s 6th Army. The first part of the operation would involve breaking the Russian line and then heading southeast, making an end run behind the South Front’s 12th, 18th, and 9th Armies. With those armies cut off, the German 17th Army under General of Infantry Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel and elements of General of Infantry Erich von Manstein’s command (mainly the XXX Army Corps under General of Infantry Hans von Salmuth) could push up the shore of the Sea of Azov. Von Kleist’s armor would be the anvil, while the 17th Army would be the hammer that would open up the rich Don basin to German forces. With that accomplished, the 1st Panzer Group would set its sights on Rostov.

On October 1, von Kleist’s units erupted from their bridgeheads. Just three days before, Timoshenko and Riabyshev had received orders to hold their positions directly from the Soviet High Command in Moscow (Stavka). It was a forlorn hope, especially with the heavy casualties already incurred in the previous months.

The Soviet forward defenses were woefully inadequate, and von Wietersheim’s panzers were able to crack them open with comparative ease. While German forces swept east, the Italian Mobile Group attached to the panzer group engaged in mopping-up operations behind the main line. In the south, von Salmuth’s XXX Corps began its drive along the Sea of Azov while elements of the 17th Army kept pressure on the western defenses of the 8th and 18th Armies.

Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler

Among the units in the XXX Corps was Lt. Gen. Sepp Dietrich’s SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH). Its strength was that of a reinforced brigade. During the first week of October, the LAH, along with other elements of the XXX Army Corps and the 3rd Romanian Army, battered the South Front while von Kleist’s panzers raised havoc in the front’s rear area.

On October 4, Dietrich’s men came up against concentrated antitank positions, which they immediately attacked. While the fighting was still going on, Dietrich appeared and began issuing orders to set up a temporary defensive line about 11,000 meters to the east after the positions had been captured. The move was necessary because the LAH had outpaced its neighbors on the left and right (the 8th Romanian Mountain Division and the 72nd Infantry Division) and had to wait for them to catch up to protect its flanks.

The next day the LAH’s reinforced reconnaissance battalion under SS Major Kurt Meyer headed toward the Molochana River, with other elements of the LAH following. Its 1st Company, commanded by SS 1st Lt. Gerd Bremer, took the village of Federico, about 12 kilometers from the town of Terpinnya, at 12:30 pm and pursued the retreating Soviet forces toward the town, which held a bridge that would ease the crossing of the river.

By 2 pm, leading elements of Bremer’s company were in Terpinnya itself. Fighting their way through the retreating Russians, the SS troops reached the bridge just as Red Army engineers blew it up, killing several of their own troops that were still on the structure.

Bremer was reinforced by SS Major Fritz Witt’s I/LAH and SS Major Teddi Wisch’s II/LAH, which took over the fight for the town. Meanwhile, Bremer moved his company out of Terpinnya, found a ford in the Molochana, and crossed. About three kilometers east of the crossing his men came under heavy mortar and artillery fire and direct fire from antitank positions. Leaving Wisch to clear Terpinnya, Witt pushed his battalion across the river at Bremer’s ford and established a strong bridgehead late in the afternoon.

“Ride on by!”

The South Front was now in total disarray, and Riabyshev seemed to be incapable of doing anything to rectify the situation. The same day Bremer was crossing the Molochana, Col. Gen. Iakov Timofeevich Cherevichenko arrived at the South Front headquarters. He informed Riabyshev that he was there to take command of the front immediately. The change of command would bring results in the future, but the current crisis could not be easily resolved.

During the evening, SS engineers were able to build a bridge across the Molochana after Terpinnya had been cleared of enemy troops. On October 6, the LAH was on the move again. The day’s objective was the town of Novospas’ke, about 45 kilometers to the east. With Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion in the lead, the units moved forward. Near the village of Romanovko the Germans ran into antitank fire. Soviet tanks also appeared, causing some casualties to Meyer’s antitank detachment. The arrival of the battalion’s 88mm guns soon drove the Soviets off, and the village was taken. Among the Soviet prisoners taken were several members of the 9th Army’s staff. With the capture of the village, the way to Novospas’ke was open. Later that evening Dietrich was notified that the LAH was now subordinated to von Wiethersheim’s corps. A day later it came under the command of von Mackensen’s III Corps.

On October 7, the LAH was ordered to pursue the Russians in the direction of Berdans’k and Mariupol. At the same time, a battalion of Brig. Gen. Friedrich Kühn’s 14th Panzer Division moved south to link up with the division. Berdans’k was captured by midday, and Dietrich’s men continued moving toward Mariupol.

After a few hours rest, Meyer held a commander’s conference in the early hours of the 8th. He had received a report stating that there were only weak enemy forces inside the city. Logically, Meyer should have waited for other elements of the LAH to catch up to his battalion for a concentrated assault on Mariupol. His men were exhausted after days of continuous combat, but Meyer had faith in them. He ordered his company commanders to form up and head for Mariupol at top speed.

SS Corporal Wontorra recounted his experiences in the LAH divisional history. “My orders were simply to push on past the Russians,” he said. Eventually the motorcyclists ran into a group of around 30 Russians marching toward the city. “I remembered Meyer’s words ‘Ride on by!’” he continued. “By now my driver was asking me what he should do. ‘Give her gas and drive on by’ was my answer. When we caught up with the Russians they looked at us in disbelief and had no time to grab their rifles. We rode on past. It had worked beautifully.… We passed one column after another. We often passed artillery being pulled by tractors.”

Before long, Wontorra’s motorcyclists were in the city itself. Behind him came the rest of the battalion, followed by Wisch’s II/LAH. By noon the city of approximately 250,000 people was firmly in German hands, and a bridgehead had been established on the eastern bank of the Kalmius River.

The Death of Andrei Smirnov

German tanks with traversing turrets.

The bulk of the 18th and 9th Armies was now effectively isolated, with von Kleist’s forces in their rear and XXX Corps at their front. Soviet units were suffering horrendous casualties, and general officers were not immune from the carnage. The commander of the 18th Army, Lt. Gen. Andrei Kirillovich Smirnov, was at his command post near the village of Popovka when German artillery killed him. He was later buried by German troops, who placed a marker on his grave that asked their soldiers to fight as bravely as this Soviet soldier. The inscription was in German, Romanian, and Russian.

Smirnov’s artillery commander, Maj. Gen. Aleksei Semenovich Titov, died the same day when he was hit by artillery fire as he was overseeing the withdrawal of his forces. As German infantry advanced, he joined his gun crews in an effort to drive them off. He was killed by a direct hit on the gun he was manning.

The following day, Chief of Staff of the Army General Franz Halder wrote in his diary, “We must exploit the unexpectedly swift capture of Mariupol by the SS Adolf Hitler by pushing through as quickly as possible to Rostov, and perhaps even crossing the Sea of Azov. The Italian divisions unfortunately are so ineffectual that they can be employed for nothing more than passive flank cover behind rivers, but not for broadening the attacking front of the [1st] Panzer Army [Panzer Group 1 was not officially renamed 1st Panzer Army until the last week of October].”

“The Battle at the Sea of Azov is Over”

It did not take Berlin long to announce another great German victory to the world. An October 11 communiqué from the Wehrmacht High Command began with “the battle at the Sea of Azov is over.” It went on to state that the losses to the 9th and 18th Armies included 64,325 prisoners, 126 tanks, and 519 guns. It also mentioned that Army Group South had captured 106,365 prisoners and destroyed or captured 212 tanks and 672 guns since September 26.

The 13th Panzer Division under Brig. Gen. Walter Düvert had now moved up to Mariupol and had established contact with the LAH. With the rest of the division moving into the city, Dietrich’s men were ordered to advance to the next objective—the city of Taganrog, which was a little more than 100 kilometers away. Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion met no opposition as it sped eastward, and it reached the town of Nossavo, about 11 kilometers northwest of Taganrog, by 3:30 pm. A platoon was then sent to reconnoiter the nearby town of Nikolaevka. It reported that the western edge of the town was heavily fortified and that any attack route would be clearly visible to enemy positions on the east bank of the Mius River. There would not be another Mariupol-like coup this time.

The bridges at Nikolaevka were of critical importance if the advance to Taganrog was to continue. On October 12, orders were given for the LAH to establish a bridgehead across the river, while the 13th and 14th Panzer Divisions moved up to protect its flanks. Meyer’s reinforced battalion attacked the Soviet forces on the west bank of the river supported by Witt’s I/LAH.

Successful penetrations were made, but the SS were soon met with a hail of fire from the eastern bank that stopped the assault in its tracks. It soon became evident that the attack would not succeed, and after a few hours of fighting Meyer and Witt were ordered to withdraw.

Crossing the Mius

Meanwhile, Dietrich had received reports that the Soviets had constructed an emergency bridge across the Mius at Prokovskoya, about 18 kilometers to the north. He immediately sent Wisch’s II/LAH to check on the report, which turned out to be correct. Once again, however, Soviet defensive fire made it impossible to take the bridge by storm. Despite the day’s setbacks, Dietrich was still determined to get across the river.

Waiting until darkness fell, SS 1st Lt. Heinrich Springer took his 3rd Company along the bank of the Mius north of Nikolaevka. Sending a platoon across by raft, Springer was able to establish a bridgehead on the eastern bank. By 9 pm, his entire company had crossed the river and had taken a commanding position overlooking the town. Witt immediately sent the other companies of his 1st Battalion across to reinforce Springer. The III/LAH, under SS Captain Albert Frey, soon followed.

The following day, Wisch used his battalion to make another effort to capture the bridge at Prokhovskoya. With the help of assault guns the battalion was able to close on the bridge, but intense enemy fire once again prevented its capture. Wisch suspended the attack after suffering heavy casualties, and late in the day he turned the sector over to Düvert’s 13th Panzer.

Realizing a bridgehead north of Nikolaevka had been established, the Soviets attacked Witt and Wisch—first in company strength and then in battalion strength. The attacks were supported by Red Air Force bombers, artillery, and an armored train, but were repulsed with bloody losses.

Düvert turned his engineers loose later in the day, and by midnight an eight-ton bridge had been built over the Mius, allowing more German infantry to occupy the eastern bank. With the added strength protecting its flank, it was time for the LAH to move on Nikolaevka.

During the 14th, Witt’s men fought their way into the center of the town, meeting heavy resistance along the way. The Soviets fought for every house, stubbornly refusing to give way until the last man was either killed or wounded. The Red Air Force also appeared time and again, bombing friend and foe alike. Fighting raged throughout the night, giving the men on either side no time for rest.

Armor was now becoming available to the German forces on the east bank. Düvert’s engineers had constructed a heavier bridge, capable of supporting his panzers, which were now crossing the river, albeit under Soviet artillery fire. This reinforcement kept the Russians from reinforcing Nikolaevka from the north and east, allowing Witt’s battalion to take the town by midafternoon on the 15th.

The Soviet troops trying to stem the advance of Panzer Group 1 had suffered greatly, but the remarkable resilience of the Red Army was beginning to make itself known. During the third week of October a new army, the 56th, was formed under the command of Lt. Gen. Fedor Nikitovich Remezov. The 56th, consisting of six rifle and six cavalry divisions, was given the task of defending the approaches to Rostov.

Assault on Taganrog

With Nikolaevka taken and more German units flowing across the Mius, the advance on Taganrog could now continue. The LAH still had the mission of capturing the city, and at 5:30 am on October 17, Witt’s reinforced I/LAH moved out with the southern section of the city as its objective. SS Major Günther Anhalt’s IV/LAH was ordered to take the southwestern shore along the Gulf of Taganrog, while Wisch and Frey would hit the city from the east.

The attack went according to plan, with units of all four battalions fighting in the city itself by midmorning. By 3 pm, the Soviets had been pushed into the southeastern part of Taganrog, and Witt’s battalion had occupied the city’s harbor installations. A member of the LAH wrote: “As we approached the city, the roar of explosions announced the Russians’ intent to abandon it. The clouds of smoke from burning fuel and ammunition stores stood like giant mushrooms above the city and darkened the azure sky.”

With most of Taganrog in German hands, new orders came down from corps command. The 13th Panzer Division was to expand the bridgehead at Sambek, about 15 kilometers northeast of the city, with the 14th Panzer guarding the corps’ northern flank. Meanwhile, the LAH was to continue to mop up any nests of Soviet resistance remaining in Taganrog.

Those units, along with the rest of von Kleist’s panzer group, needed both rest and supplies. Fuel was at a premium for most of the divisions in the command, and the supply route stretched hundreds of kilometers to the west. Weather was another issue. German units farther north had already experienced the mud of the Rasputitsa, and in the central and northern regions of the Eastern Front snow had already fallen in some areas. Vehicles, especially wheeled vehicles, became mired in the mud that was once a sandy road, and the long supply lines made getting the necessary fuel, ordnance, and other materials to continue the advance an arduous trip.

Supply Lines Stretched

On October 19, von Mackensen issued the following order for the capture of Rostov. “The 13th Panzer Division and the LAH are to attack at 0530 hours on 20.10 by moving the bulk of their forces across the line reached today. The LAH is to halt its progress when it is level with the 13th Panzer Division.” Once again, the 14th Panzer would provide cover for the corps’ northern flank.

The corps moved out on time, and during the 20th both divisions had achieved the days’ objectives. Meyer, commanding the reconnaissance battalion, was replaced by SS Captain Hugo Kraas during the day due to illness. As the divisions settled in for the evening, cold winds began blowing across the steppe. It was a harbinger of things to come. As the men lay shivering in their summer uniforms, von Mackensen sent the following message to von Kleist: “Supply of winter clothing scheduled for between 21. and 31.10. In Dneptropetrovsk it is too late. If winter clothing does not come soon, the troops’ ability to perform will be too greatly taxed. Urgently request supply of winter clothing to Mariupol, at the least.” It was one of many such pleas from commanders all along the Eastern Front.

Despite the weather, von Mackensen’s divisions continued to advance. For the next two days more ground was taken. Captured prisoners told German interrogators that some of the divisions facing them had been raised within the last couple of months. Many of those prisoners were Kuban Cossacks—men who did not have an especially favorable attitude toward the Soviets.

At the South Front headquarters, Cherevichenko issued orders to his subordinates to hold the line at all costs now that the weather was changing. He knew German supply lines were stretched to the limit and that the more men and equipment expended by the enemy facing him the less they would have for a final push to their obvious objective of Rostov.

The Germans were getting perilously close to the city, and Cherevichenko needed to buy time for Remezov to deploy his new army. Therefore, he ordered a series of counterattacks on the 23rd that caused von Mackensen to reel in his forces and go over to the defensive for the time being. His divisions held a front of about 70 kilometers, but not all of his units were manning the front line as several elements were still struggling to catch up to the lead forces. The supply situation was also getting critical.

An October 23 corps memo stated, “The Panzerarmee has informed us that the supply situation will remain unpredictable due to the unfavorable weather and bad road conditions on the long supply routes and despite all the auxiliary measures and personnel put into action; it may even occur that the supply lines may be temporarily out of service.”

The memo also made several recommendations that should be implemented down to company level. It said units must be self-reliant for ammunition, fuel, and provisions for up to several days at a time. Strict rationing was also recommended, and prisoners were to be used along supply routes to help retrieve vehicles that had become stuck in the quagmires that were once roads.

Soviet attacks hit the entire line held by the 13th Panzer Division, which centered around Cahltyr’ about 16 kilometers northwest of Rostov. Düvert’s infantry was pounded by artillery as the Russians strove to smash his lines, but timely counterattacks from the unit’s armor helped keep the front stable. Although the Russian attacks failed to break the German line, Cherevichenko was achieving his objective. The longer the Germans were forced to be on the defensive, the more time he had to prepare the positions around Rostov.

“Chomped on by Lice and Freezing to Death”

The heavy fighting during the past few weeks was also affecting the morale of the German troops. “We lay for weeks in the cold Steppes,” wrote SS 2nd Lt. Bäder of the 14/LAH. “Chomped on by lice and freezing to death, our unit was decimated.”

A situation report from the III Corps also expressed pessimism. “The 13th Panzer Division and the LAH have been physically overtaxed for weeks,” it said. “Daily care with good food and canteen allotments is lacking. Their clothing is torn; as socks most of them are wearing foot rags torn from Russian uniforms or Russian bandages. Most of the troops are freezing at night.

“Morale is down, especially because of the optimistic propaganda given out, which contradicts their experience on the battlefield…. The effect of the Russian Air Force, rocket launchers and tank platoons on the men’s morale is enormous…. The small number of officers is dwindling…. The Panzer regiment is unfit because of lack of fuel…. Neither the 13th Panzer nor the LAH is in a position to move all of its combat vehicles…. The panzers use up enormous amounts of fuel every night. We cannot shut them off, even for a short time, for we are lacking anti-freeze…. A motorized unit needs fuel even when it is standing still.”

Torrential rains fell during the last days of October, exacerbating the misery of the troops on both sides. The rain made offensive operations nearly impossible during the opening days of November, giving both attacker and defender a much needed break in the fighting.

The lull also gave von Mackensen time to remedy some of the problems that had plagued his corps. Fuel was finally arriving in sufficient quantities to continue the drive to Rostov. At 1st Panzer Army headquarters, von Kleist was fine tuning a new plan in the face of reports that Remezov’s 56th Army now occupied strong positions along the eastern approaches to the city.

Bolstered by General of Mountain Troops Ludwig Kübler’s IL Mountain Corps, von Kleist planned to sweep down on the city from the north. Using von Wietersheim’s XIV Corps as protection in the north, the 14th Panzer Division, Maj. Gen. Friedrich-Georg Eberhardt’s 60th Infantry Division (mot.), and SS Maj. Gen. Felix Steiner’s 5th SS Wiking Division were to attack from the General’skoye-Serafimov area and swing southeast. Brig. Gen. Hans-Valentin Hube’s 16th Panzer Division would cover von Wiethersheim’s northern flank. Farther south, von Mackensen’s corps would perform a similar movement, with the LAH coming down from the northwest and the 13th Panzer attacking entrenched Soviets in the Mokryy Chaltyr’-Kalinin sector.

“The Cold Tore at Our Nerves, and Morale Dropped”

The opening moves of von Kleist’s panzer army went well on November 11, with the 14th Panzer and Wiking establishing bridgeheads on the eastern bank of the Kropkaya River. Kraas’s LAH reconnaissance battalion also gained its first day’s objective, but the weather turned once again, halting the advance in all sectors. A member of the battalion, Kannonier Gottzmann, wrote: “During the night we sank in mud. There was no chance of moving forward, even if we lost contact with the enemy.… A few days later a cold wave arrived and froze everything…. The cold tore at our nerves, and morale dropped…. And Rostov still lay before us. Unattainable!”

Von Mackensen’s corps was virtually immobilized, as were other units slated for the attack. The element of surprise was gone, and the Russians were able to bring reinforcements in to bolster areas that were likely targets for renewed German attacks. Meanwhile, von Mackensen was given command of the 14th Panzer and Eberhardt’s 60th Motorized Infantry Division to strengthen his striking force.

The weather finally broke on the 17th, and von Mackensen ordered his divisions to attack all along the III Corps front. Dietrich’s LAH, reinforced by Panzer Rgt. 4 (13th Panzer Division), made good progress against determined enemy resistance. On Dietrich’s left the 14th Panzer took Bolshiye’ Saly in a surprise assault. The Soviets reacted with violent counterattacks against the division the following day, but Kühn’s men held their ground.

Dietrich ordered his troops to keep moving. By the end of the 18th, elements of the LAH had taken Krasnyy Krim, only 2½ kilometers from the outskirts of Rostov. Other LAH units, however, were held up by Soviet troops in the heavily defended village of Sultan Saly, about 10 kilometers northwest of the city.

City Fighting in Rostov

Cherevichenko now faced a dilemma. He could see his armies destroyed or he could conduct a fighting withdrawal, biding his time while reorganizing the South Front for a counterattack. In fact, Stavka was already planning a counterstroke across the entire Eastern Front. In the far south, Timoshenko’s South West Front and Cherevichenko’s front would be tasked with the destruction of von Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army, but since the counterattack was still in its planning stages the fate of Rostov was still an unknown factor.

On November 19, Sultan Saly fell after bitter fighting took many lives on both sides. The fall of the fortified village broke the back of the Soviet defensive line northwest of Rostov. As the LAH pressed forward, the 14th Panzer sliced through Remezov’s units stationed north of the city. By the end of the day, Kuhn’s division had penetrated into some of Rostov’s northern suburbs while the 60th Motorized Division spread out to the east, establishing a defensive line stretching from Aksyiskaya on the Don River north through Shchepkin to Kammenyy Brod. The line was then taken over by Hube’s 16th Panzer Division.

The next day the LAH and 14th Panzer fought their way into the center of the city by noon. With the 13th Panzer pushing in from the west, Remezov had no choice but to pull his units back toward the Don. House to house fighting ensued, but the LAH continued to make good progress, bypassing strongpoints as it attempted to capture one or more of the bridges that spanned the river.

Springer’s Bridgehead

Springer, with his 3rd Company, heard explosions coming from the direction of the Don as Red Army engineers began their work of destruction. Pushing his men forward, Springer managed to reach a point overlooking the river. As evening fell, he found himself staring at a massive railroad bridge that was crawling with both soldiers and civilians. Through his field glasses, Springer could see the bridge had already been prepared for demolition.

“I had to make a hasty decision,” Springer wrote in a 1992 letter to the author. “Most of the LAH was still engaged in heavy fighting within the city. We saw a train approaching the bridge, and I ordered my men to fire on it with all weapons. The engine was hit numerous times, and it finally halted with steam belching out from several holes.”

The attack caused confusion among the civilians and soldiers on the bridge. Taking advantage, Springer ordered his company, along with an accompanying unit of engineers, to cross the structure. Under covering fire from the 3rd Company the engineers cut demolition wires as they advanced. Reaching the opposite side, Springer’s men took several Red Army soldiers assigned to guard the bridge prisoner.

Establishing a small bridgehead, the assault group fought off several attacks. “We were essentially cut off,” Springer wrote. “Fighting was still going on in the city, and reinforcements could not be sent.”

To make matters worse, von Wiethersheim’s XIV Corps was coming under heavy attack from units of Maj. Gen. Fedor Mikhailovich Kharitonov’s 9th Army. The attack prompted von Kleist to order the 13th Panzer to move north to help alleviate the situation. With the loss of the division and the LAH still engaged in trying to clear Rostov proper, it was impossible for Springer to cling to his bridgehead.

Early on November 21 Springer received orders to abandon his position and make his way back to the northern bank of the Don. “We had achieved our objective,” Springer wrote, “but events overtook us. Our hard-won position had to be given back to the Russians.”

Remezov’s men quickly reoccupied the southern portion of the bridge. Engineers set new charges and repaired cut wires, and a few hours later the mighty bridge was destroyed in a thunderous blast.

The Threat of Encirclement

Another bridge fell into German hands thanks to Captain Willy Langkeit, acting commander of the 14th Panzer’s II/Pz. Rgt.36. During the advance on the city, Langkeit’s battalion was hit by a Soviet counterattack on November 18. Ordering his panzers to hold their fire, he let the Russian tanks advance to within 600 meters. When the panzers opened fire, shells tore into the Soviet formation, stopping it cold. The Russians came forward two more times, meeting the same fate. When they finally gave up they left 17 smoldering tanks on the field, including some T-34s and heavy KV Is and KV IIs.

As his panzers entered Rostov on November 20, his accompanying infantry support became engaged in house to house fighting. Pushing forward, Lankeit formed a battle group around his battalion that included infantry of Schützen-Regiment 108 and motorcycle infantry of Motorcycle Battalion 64.

On November 21, Lankeit took a bridge over the Don that was also set for demolition. The appearance of German tanks was too much for the Russians guarding the bridge, and they fled or were cut down before the charges could be set off. Smashing its way through several other Russian positions, the battle group reached the southern edge of a large island in the middle of the Don before being halted by strong opposition. Like Springer, Lankeit was forced to give up his prize due to lack of reinforcements and the changing nature of the battle for the city.

By now, attacks from the 9th and 56th Armies were increasing. The dangerous situation north of Rostov had turned into an impending disaster as the XIV Corps and Kübler’s Mountain Corps struggled to hold their positions. On the 9th Army’s right flank, Maj. Gen. Anton Ivanovich Lopatin’s 37th Army and Maj. Gen. Fedor Vasilevich Kamkov’s 18th Army joined in to attack the 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions and the Wiking Division with a combined force of 10 rifle divisions, two cavalry divisions, and two tank brigades.

On November 22, Halder wrote in his diary, “1st Panzerarmee was forced into the defense by the Russian attacks with superior forces and will have a hard time of seeing it through.” However, in the same entry he remained somewhat optimistic as well as realistic. “The measures instituted are well taken and promise to be successful. However, after 1st Panzerarmee has disposed of the attacker, it would probably be too much to expect it to clear the enemy out of the Donets bend with what is left of its forces.”

The same day Halder wrote those words, von Mackensen came to the conclusion that his entire corps was in grave danger. Von Kleist also recognized the probable goal of the South and South West Fronts. The maps did not lie. With four Soviet armies attacking, the main points of the assault indicated that a strong force was about to swing southwest in an attempt to encircle the III Corps. It was also apparent that the ultimate goal was to destroy the entire panzer army.

Red Army Charge Across the Ice

At noon on the 22nd, von Kleist issued orders to prepare for a withdrawal. His Panzer Army Order No. 31 stated, “In the face of the strong forces which the Russians have massed before my army, I have decided to move my units back in an orderly manner from the extended arc position, at first behind the Tuslov (River), then to a consolidated position behind the Mius…. The next few days will place great demands on the officers and the men. The hour of our testing has just arrived.”

With the 13th Panzer gone and the 60th Motorized engaged on its northern flank, it was up to the LAH to hold Remezov’s 56th Army at bay as long as possible. Von Kleist’s forces, stretched out to the northeast, needed time to make the fighting withdrawal to the Mius line, and if Dietrich’s men caved Remezov could send his divisions streaming up from the south, cutting 1st Panzer Army’s escape route.

The I, II, and III Battalions set up positions along the northern bank of the now frozen Don. They were joined by the antiaircraft and reconnaissance battalions. To the northeast, the IV and engineer battalions continued to fight Soviet units still entrenched inside Rostov. The battalions, already depleted by weeks of battle, were stretched incredibly thin, and Remezov sent out constant patrols looking for weaknesses in the German line.

On November 25, Colonel Mikhail Ivanovich Ozimin’s 31st Rifle Division and Colonel Petr Pavlovich Churvaskev’s 343rd Rifle Division attacked the positions of the reconnaissance battalion. At 5:20 am, supported by artillery, the Red Army soldiers advanced across the ice. According to Meyer, the front ranks came on with arms linked, “forming a continuous chain which stamped across the ice in wild singing.”

German machine guns opened up on the mass, cutting wide swaths through their lines. Behind the fallen, more soldiers appeared, trampling their comrades as they sought to reach the German positions. A force of two Soviet battalions managed to penetrate the German line, threatening to dislodge the entire set of defenses, but a counterattack by the reconnaissance battalion’s 2nd Company, which was supported by LAH artillery, managed to seal the breach. The company reported capturing six officers and 393 men and counted 310 dead enemy soldiers at the end of the action.

The attacks continued for the next two days, augmented by artillery and air attacks. Although the LAH continued to hold, events in the north soon made Rostov untenable. In von Wiethersheim’s sector the 14th Panzer Division had been pushed out of General’skoye and was in retreat with the Soviets nipping at its heels. The 13th Panzer and Hube’s 16th Panzer were also in retreat, as was Steiner’s Wiking Division. However, the Russians were thwarted in their attempt to outflank the corps, thanks in large part to the efforts of SS Major Plöw, who defended the Balabanov Heights against several heavy attacks with a combat group from the 5th SS. His stand allowed the mass of von Wiethersheim’s corps to fall back to the Tuslov position.

A Skillful Retreat

By now, von Rundstedt was ordering a general retreat all along Army Group South’s front. On November 28, the LAH began its own retreat, fighting off concentrated attacks from both the 56th and 9th Armies. By this time, Cherevichenko had concentrated about two dozen divisions against von Mackensen. He was well aware of the great propaganda coup that would come from news that his South Front had succeeded in wresting the first major Soviet city from German hands. During the afternoon and evening of the 28th, the 56th and 9th Armies had reoccupied most of the city.

Hitler received word of von Rundstedt’s order to retreat on the 29th. Although von Rundstedt had given a clear picture of the enormous danger facing the 1st Panzer Army, the Führer flew into a rage, berating the esteemed field marshal in front of his personal staff. Later in the day he sent orders countermanding the withdrawal, but it was already too late.

Cherevichenko kept pushing his armies. The Germans were conducting a skillful retreat, and the Soviets received a bloody nose in several sectors of von Kleist’s front from counterattacks by ad hoc formations when advance elements got too close. By using this method, von Kleist succeeded in crossing the Tuslov and occupying the western bank.

It was only a stopgap measure. The Tuslov was not that wide or deep, and its west bank offered little in regard to a decent defensive position. With the Soviets adding new divisions to their assault forces and Red Air Force planes practically owning the sky, von Kleist began another staggered withdrawal. Leaving a heavy rear guard, the 1st Panzer Army moved back toward the more defensible Mius River.

“The numerically weak forces of 1st Panzer Army had to give way before the concentric attack launched in very great strength from the south (apparently a main effort), west and north,” Halder wrote on the 29th. He was correct as far as German strength went. Most of von Kleist’s divisions were down to two-thirds or even half strength. The Westland Regiment of the 5th SS reported that from July 1 to November 30 the unit had suffered 29 officers, 65 NCOs, and 347 men killed. In addition, a further 21 officers, 138 NCOs, and 920 men were wounded and 29 men were reported missing—a grand total of 50 percent casualties for the regiment in four months.

Reichenau Replaces Rundstedt

November 30 saw renewed Russian attacks on the flimsy Tuslov Line. The Soviets battered away at the German defenses, and the ferocity of the attacks forced von Kleist to commit the 14th Panzer (1st Panzer Army’s reserve) into the fray to stem the enemy advance. Even with that commitment, penetrations were achieved in several places. Bowing to the inevitable, von Kleist ordered all remaining units along the Tuslov to fall back to the Mius.

Halder noted, “The Führer is in a state of extreme agitation over the situation. He forbids withdrawal of the army to the line Taganrog-Mius-mouth of the Bakhmut River and demands that the retrograde move be halted further east.”

At 1 pm on the 30th, Hitler met with members of the Army High Command. Halder reported the meeting to be “more than disagreeable, with the Führer pouring out reproaches and abuse and shouting orders as fast as they came into his head.”

The meeting ended with the High Command agreeing to Hitler’s demands that the retreat to the Mius Line be halted. When he received the new order, von Rundstedt replied that compliance was not possible. He also said that if the new order was not rescinded, he would ask to be relieved. The following day, Hitler dismissed von Rundstedt and replaced him with an ardent National Socialist, Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau, who took over command immediately.

“A Senseless Waste of Strength and Time”

Replacing the commander of Army Group South would not change the situation. The army group had shot its bolt. Von Reichenau, after a quick review of his new command’s position, agreed with von Rundstedt’s evaluation. He reported as much to Hitler.

Halder commented on Hitler’s afternoon staff conference on December 1. “At 1530 hours the Commander of the Army (Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch) was with the Führer, and von Reichenau telephoned during the conference. He requested permission to pull forces back to the Mius position. Führer concurs. Now we are where we could have been last night. It was a senseless waste of strength and time, and to top it, we lost von Rundstedt also.”

Long supply lines, wear on vehicles, inadequate winter clothing, and the Russian winter itself were all factors in the failure to hold Rostov. Perhaps the biggest factor was the Germans’ underestimation of the resiliency of the Red Army. Most of its incompetent general officers either perished or were removed and imprisoned or shot during the opening phase of Barbarossa. Those who replaced them were tough survivors. The massive losses of the summer were made up by the seemingly endless supply of Russian manpower, and although many divisions were ill trained and understrength, the sheer volume of troops was enough to stop the German advance.

With the opening of the Russian winter offensive on December 5, the Red Army moved forward, sending German forces reeling in most cases. The 1st Panzer Army held its position on the Mius, but the prize of Rostov had been lost, at least for the time being. However, Hitler would not give up his dream of taking the city and capturing the oilfields in the Caucasus, but he would have to wait until the following year to try again.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments