By Kevin M. Hymel

The Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) carrying Army engineers and Navy beachmasters hit a mine on its way into Omaha Beach. The explosion rocked the craft, killing the men in the front and tossing others into the water. Beachmaster Robert L. Watson flew backward into the air, cutting his left leg on the LCM’s bulwark before plunging into the freezing water.

The saltwater stung his wounds. The 60 pounds of equipment on his back pulled him into the depths, but he quickly inflated the lifebelt around his chest and popped to the surface. “I’m in shock,” recalled Watson, “and I’m scared to death.” It was early morning on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and he could not tell which of the other men bobbing in the water was alive or dead. Worse, he knew that other landing craft were not allowed to stop and pick up survivors.

“I thought I was the last man in hell,” he recalled.

Watson soon spotted a Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) headed straight for him. He screamed at the coxswain, “Hey! Stop! Hey! I’m over here!” The craft slowed long enough for him to grab a rope drooping from the side. He clung to the side of the craft with one hand, gagging as salt water splashed his face. His new ride dragged him all the way to the beach, tearing the skin off his hands in the process.

Watson let go of the rope about 40 yards from the beach in shallow water. He found a nightmare. German artillery shells exploded on the beach while machine-gun fire stitched the sand. Sherman tanks burned on the water line and half-sunk landing craft bobbed in the water, red with blood. The dead and body parts littered the beach.

“It was horrible,” Watson remembered. “Everyone’s screaming for help, everyone’s wounded.”

Watson crawled on his hands and knees up the beach, his uniform in tatters but his helmet still on. “Bob, get your head together,” he told himself and kept repeating, “I don’t want to die here, I don’t want to die here.” Once out of the water, he pulled his bolt-action Springfield rifle from its protective plastic bag.

Watson then crawled up to an Army medic who had lost everything but the strings of morphine syrettes he wore around his neck. He gave Watson one and, shouting over the din of battle, told him, “Just give it to a medic.” Watson, in return, fished some sulfa powder and pressure bandages from his first aid kit and handed them to the medic. Watson climbed farther up the beach, over dead and wounded Americans, and removed all the first aid kits he could find, throwing them back to the medic.

Watson had arrived an hour into the battle. Companies E and F of Colonel George Taylor’s 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division had landed on Fox Green and Easy Red Beaches opposite the Colleville Draw and encountered a slaughter. The Germans defended either side of the draw with two major defensive positions, Widerstandsnests (WN) 61 and 62. On Watson’s left, WN 61 stood low to the beach firing an 88mm cannon from a concrete bunker. On his right, WN 62 stood atop a hill dominating the area with its 75mm cannon.

Although some heavy guns had been knocked out before Watson arrived, enemy artillery, mortars, machine guns, and sniper fire rained onto the beach. Many American soldiers were killed as they charged out of their landing craft. Some never made it out. Those who survived struggled up the beach, exhausted and weighted down by equipment and soaking wet uniforms. Many more were cut down. Almost all the officers in F Company were either killed or wounded.

Watson continued up the beach until he met an Army captain who ordered him to the firing line. Watson pointed at his helmet, which bore the distinct Navy orange crescent and a black number six on the front and gray band around the base, identifying him as a Navy beachmaster. The captain was unimpressed. “Get your ass up there or I’ll blow your head off!” he demanded.

“Where the Hell is Pearl Harbor?”

The carnage of ground combat had been the farthest thing from Bobby Watson’s mind some 21/2 years earlier as he trimmed rose bushes in a garden with his father across the street from their Lynn, Massachusetts, home. Watson’s mother interrupted their work when she called out from their house to come listen to the radio. They rushed inside to hear that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. Like so many Americans, Watson’s first thought was, “Where the hell is Pearl Harbor?”

Watson, a 17-year-old student at English High School, was working as the head usher at the local movie theater when the country went to war. As the months passed, he spent his time watching war newsreels, seeing bayonet charges, weapons firing, and men getting killed. When his draft notice arrived in July 1943, he decided to join the U.S. Navy, where he figured he would get three hot meals a day and sleep on a bed. He realized that in the Army and Marine Corps, “You can’t get a deal like that.” But before he left, he watched his last movie, Humphrey Bogart’s Casablanca.

Watson joined the Navy at the Newport Naval Station, Rhode Island. After six weeks of training, he and his fellow draftees were declared sailors. Upon graduation, the new swabbies lined up in front of their barracks and an officer offered them two options: men less than six feet in height were offered the submarine service; everyone else was offered the Naval Armed Guard.

The next day, the men entered a large auditorium where they were assigned to outgoing units. Watson did not like his chances for a good assignment. “You know if your name ends with W, X, Y, and Z, you’re in a world of hurt.”

When the officer calling names finally reached the letter W, he called out, “Six-man draft of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, Camp Bradford, Virginia, amphibious training station! About face!” Watson and five other sailors headed off to their new school. When he asked the coxswain in charge where they were going, the coxswain said, “You got it made! You’re gonna be a gator! You’re gonna crawl out of the water and onto the beach.”

Training as a Beachmaster

The men soon arrived at Camp Bradford, where they slept on coiled springs in their Armbruster tents while awaiting their mattresses. At the quartermaster, Watson received Army gear, complete with an Army jacket and paratrooper boots. When he was issued a double-bladed knife to strap to his leg for combat, he wondered, “What happened to the Navy that served three meals a day?”

Naval beach battalions worked the landing beaches after an amphibious assault, managing the incoming ships that delivered men and vehicles. They coordinated with Army commanders on the battlefield and ordered weapons or equipment needed from inbound ships. They also handled casualty and prisoner of war (POW) evacuations.

Commander Eugene C. Carusi led the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, which was made up of three companies—A, B, and C—and a battalion headquarters. Watson was assigned to Company B’s 6th Platoon, known as B-6, under the command of Lieutenant (j.g.) George Wade, the beachmaster, and Ensign James E. Allison, the assistant beachmaster. Both Wade and Allison had graduated from the accelerated officer’s course and were known as 90-Day Wonders. Watson thought highly of them: “They were two of the nicest guys you wanted to meet.”

The training was intense. The sailors learned to fire various weapons, conducted gas mask drills, practiced aircraft recognition, and crawled under logs while live rounds snapped above their heads. When they were ordered to climb over a wall draped with a cargo net, Watson thought, “What the hell do I need that for?” He would later learn.

Watson trained to fire a number of weapons, including a bolt-action M1903 Springfield rifle. “I had never fired a damn rifle,” he admitted, yet enjoyed hitting the targets. The Marine sergeant watching Watson’s skill asked him to sign a form. “I’d put you in the Marine Corps as a sniper.” Watson told him no thanks. Knowing that the Marines fought in hand-to-hand combat with knives, he thought to himself, “I’m 18 years old, I’m a Christian. Can I do that?”

The most important training involved loading onto an LCVP, also known as a Higgins Boat, which would head out about a half mile into Chesapeake Bay, then turn around and head back to the beach. LCVPs held up to 35 men and had a retractable bow ramp. When the men heard an air horn blown by either Lieutenant Wade or Ensign Allison on the beach, the ramp dropped and the men charged out. They had to be off the craft in 36 seconds.

“If they blew the horn halfway in,” recalled Watson, “the coxswain would stop, drop the ramp, and we would swim to shore.” To keep from drowning, the men inflated their life belts by squeezing two switches inside the belt, which activated two carbon dioxide bottles.

“We Lost About 10 Ships Out of About 100”

After six months of constant training, the men headed to Long Island, New York, where they waited for a transport ship. Watson had time to meet his mother and sister, who had come down from Massachusetts for the day. Finally, on January 7, 1944, Watson and his mates lined up on Pier 92 and boarded the SS Mauretania, a luxury liner converted into a troopship. After descending a seemingly endless amount of stairs and ladders, he reported to an assigning officer and asked for a top bunk. The officer said that Watson and three other sailors would get the top bunk. They would rotate sleeping to maximize space.

The Mauretania was part of a huge convoy headed to England via Nova Scotia. The convoy could only sail as fast as its slowest ship. During the 13-day trip there were several German U-boat warnings. Over the intercom came the order, “Batten down the hatch! Lock that sucker down!” The alerts left an impression on Watson. “It was quite scary,” he remembered.

One night while up on deck, Watson could see something burning on the horizon. “We lost about 10 ships out of about 100.”

“This is the Beach”: Preparing For the Landing on Omaha

When the ship finally docked at Liverpool, Watson and his fellow sailors loaded onto trucks and headed south to a small town where they billeted for less than a month before shipping out to Swansea, Wales, on April 12. They set up in a cow pasture, living in tents. “Brrrrr!” said Watson, recalling the experience. “We were allowed one bucket of coal a day and all you could steal.”

The sailors discovered they were across the street from the 1st Infantry Division’s 5th Engineer Special Brigade, to which Watson’s 6th Naval Beach Battalion was now attached. Together they would support Colonel George Taylor’s 16th Infantry Regiment for the amphibious assault on the Fox Green and Easy Red sectors of Omaha Beach.

Settling in, Watson dug trenches outside his tent for air raids and spent his time getting to know the Army engineers. During a surprise inspection, he discovered that he was the only sailor who knew his rifle’s serial number. After a few months of training, the sailors and engineers transferred to Portland on the southern coast of England to await the order for the invasion. He and his comrades slept in tents and in civilians’ houses, and he could see about 500 ships in the port. There, the men learned they were destined for Normandy. They were shown a sand table of Omaha Beach, and an officer told them, “This is the beach.”

The sailors learned they were hitting the beaches across from the town of Colleville and the Colleville Draw, the road between the cliffs that overlooked the beach. They were told to look for a church steeple on the way in to stay on course.

Before boarding their ships, Watson and about 9,000 men were marshaled into a huge valley. There they found a general standing atop a tank. “You now are going to lead the great crusade!” the general said into a speaker system. Watson was shocked by the general’s loudness. “Hitler could hear everything he said!” The general continued, “You are the best trained army in the world. We are going to invade France, and I am sorry to inform you that some of you will not be coming back.”

To Watson, it was the same pep talk he had heard from his football coach. But then the general made a promise that made him feel better about the invasion: “At 0300 the Air Force will come over and bomb the beach so severely you won’t even need to take your shovel with you since there will be so many craters on that beach. There will be bomb craters everywhere! At 0430, Navy guns will open up and pulverize the German defenses. We’re going to send in a dozen LCIs with rockets, and we’re going to run those rockets onto the beach and pulverize those shore batteries. We’re going to send in one hundred tanks. It will be the biggest bombardment parade in history.”

He never learned the name of the general.

Journey Across the Channel

On June 4, Watson and his team boarded the transport USS Henrico (APA-45) for the trek across the Channel. It joined the assault force and headed out to sea but turned around when an approaching storm threatened the invasion. The Henrico returned to port for 24 hours and headed out again on the night of June 5. Onboard, Watson could see ships everywhere. “In front of us were minesweepers,” he said.

Reveille sounded at 3 am on June 6, D-Day. Watson could hear the anchor drop. An officer called out, “Everyone’s going to have a shower and everyone’s going to get fed.”

After a shower and a breakfast of steak and eggs, Watson waited down below for his number to be called. When he heard it, he went up on deck to his assigned spot, ready to load onto an LCVP. A deck officer informed his group that halfway to the beach they would see a control boat that would help guide them in. He concluded by telling the men they were about to descend cargo nets to the craft, and if they fell off, “We will not stop the war!”

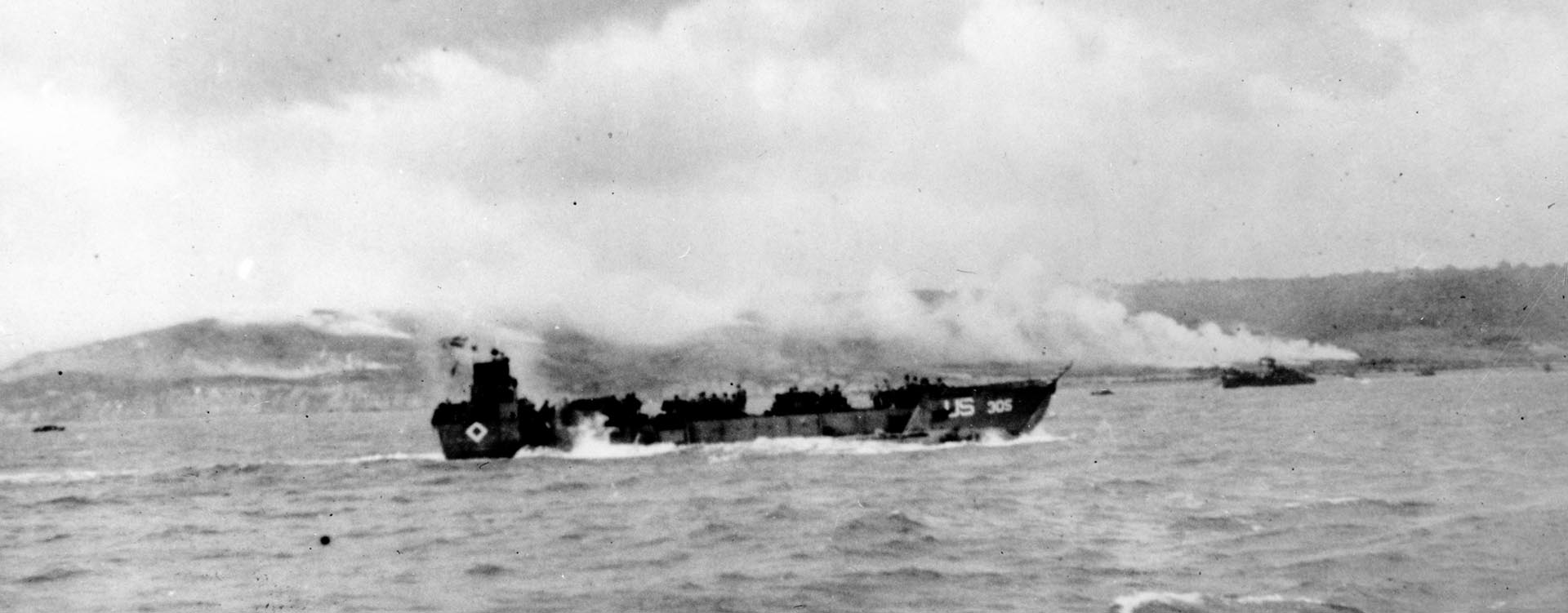

Loaded down with equipment and with his plastic-covered Springfield rifle strapped on his back, Watson went over the side to discover a LCM waiting below. LCMs were bigger than LCVPs and designed to carry vehicles or tanks. Watson dropped into the craft and took his place aft with three other beachmasters. Engineers with Big Red One patches, the symbol of the 1st Infantry Division, filled the rest of the craft.

“I had the warmest seat,” said Watson. “My butt was against the engine room bulkhead.”

The LCM took off into four-foot swells. Water splashed into the craft as the bilge pumps fought to keep the craft afloat. The men used their helmets to scoop out the ankle-deep water. Looking to his left, Watson saw an LCVP cruising three inches above the water. “The next thing I knew, it was gone.”

Watson’s craft was scheduled to land at 7:30, an hour after the battle for Fox Green and Easy Red sectors had started. The plan had been for amphibious tanks to land first, quickly followed by two infantry companies of more than 200 men to fight the enemy while engineers destroyed beach obstacles. More tanks, artillery, and other vehicles and reinforcements would follow. Watson and his men would come in and set up equipment to manage ship-to-shore operations.

“Get to the Beach!”

Nothing went as planned. In the predawn darkness, the craft carrying the tanks took longer than expected to form up, and the assault infantry hit the beach without armor protection. The various waves of landing craft became mixed up in the confusion.

“Every landing craft was taking on water like crazy,” said Watson. LCVPs began sinking. Those that stayed afloat took enemy fire. “Landing craft were exploding around me.” Watson succumbed to seasickness and threw up. He was not alone. At least he could see the church steeple in Colleville, telling him he was on target.

The enemy fire spooked the coxswain, who slowed his craft to a crawl. “Get to the beach!” the Army officers yelled at him. “Get this thing going!” Their reprimands worked. He gave it more power. That’s when Watson’s LCM, about 300 yards from the beach, hit the floating mine. He then hitched a ride from the LCVP and reached the carnage of Omaha Beach. Watson remembered what the general and the deck officer had told him about the signal boat and the battlefield preparations. None of it had come true. There was no control boat out in the water, there were no bomb craters on the beach to use as foxholes, and he never saw an Allied plane.

Watson joined the firing line as ordered by the captain. About 300 yards to his right, he could see Germans running behind WN 62 to a reinforced hut, retrieving supplies. He loaded his wet ammunition clips into his rifle and took aim. “I was scared that the ammunition wouldn’t work,” he said, but he squeezed off his first shot without any problems. He then fired about 10 clips at the enemy.

“I don’t know if I killed anyone or not,” said Watson. “I didn’t really care.”

After doing his part in reducing WN 62, Watson decided to head back to the beach and perform his job. “My orders were to get on the beach line and move to the beach station.” While he searched for his unit, he came across Lieutenant (j.g.) James F. Collins, the medical officer. He took a look at Watson’s lacerated leg and said, “Later.”

Company B sailors gathered just below WN 62. Out of the entire company, there were only 36 left. “A lot of our boys didn’t show up,” said Watson. One missing man was Lieutenant Wade. “He never made it to the beach.”

Preparing the Beach For Supplies and POWs

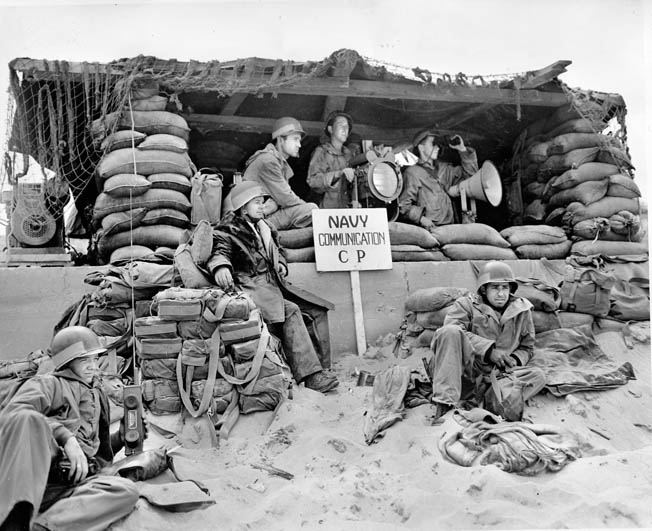

Watson did find Dick Wyatt, who had been with him on the LCM before it sank, but he did not know how he survived the sinking. The men put up large red banners and flags, signaling to incoming ships that they were approaching Easy Red Beach. Every quarter of a mile along both Fox Green and Easy Red the beachmasters set up sandbagged communication stations. “The Germans made great sandbags,” he said.

Watson and his fellow beachmasters set up colored signal lights to designate the beach at night and regular signal lights to communicate with ships in the Channel. “The Army called us and said, ‘We need ambulances,’” explained Watson, “and we would get on the lights.”

The beachmasters became so proficient they joked that they could order an ice cream sandwich with their lights and flags. “We were Amazon!” joked Watson. “Anything you needed, you could pick up the phone, and we’d get it.” When the requested ambulances drove off their craft, the beachmasters would drive a jeep in front of them and lead the convoy up the draw and to the 1st Infantry Division headquarters.

As the fighting progressed inland, wounded Americans and prisoners of war were brought down to the beach. Watson was surprised to find that many of the Germans were not German. They were foreign conscripts. Despite enemy artillery still exploding on the beach, the Americans set up a POW pen at the wide open base of the draw (a parking lot today). Both POWs and the wounded needed to be moved off the beach since there was no room for additional craft to land.

“Do You Know How to Drive a Bulldozer?”

Watson was working with Wyatt when a boatswain’s mate ordered them both to the beach. They found Ensign Allison waving a red flag, signaling the ships in the Channel to stay away as enemy artillery fire pounded the beach. With Wade dead, Allison was now in charge. “Do you know how to drive a bulldozer?” asked Allison. Even though he did not, Watson told him he could. Allison told him and Wyatt to bring an abandoned bulldozer back to him.

As the two men headed off, an artillery round exploded, almost cutting an Army corporal in half. They got him to a medic and continued to the bulldozer. Fortunately, it was still running. As Watson looked at the controls, Wyatt tapped him on the back and pointed to the water. There lay Allison, floating face down in the surf. The two men ran to him and lifted him out of the water only to discover that he had been hit in the back of the head by shrapnel. They dragged him up the beach to Dr. Collier, who took one look at him and shook his head.

Watson and Wyatt spent the rest of the day on the bulldozer. When their bulldozer fell prey to a German artillery barrage, they found another one. Once the tide receded, empty landing craft became stranded on the beach. The two beachmasters pushed them back into the water, but only if they obeyed their rules. When one coxswain ordered, “Push me back to the water,” Watson told him, “No way, you get loaded with wounded, then we’ll push you back.”

A Battlefield Promotion

Later in the afternoon, a Navy lieutenant in charge of one of the 6th’s companies asked Watson his rank. When Watson told him he was a seaman first class, the lieutenant told him, “Now you’re a coxswain.” That night, an exhausted Watson and Wyatt commandeered a German dugout to the left (facing the beach) of the top of WN 62 (near today’s 5th U.S. Engineer Special Brigade Monument). The two men slept well despite the noise of battle. Coxswain Bob Watson had survived D-Day.

The next day the two sailors continued pushing craft and ships into the Channel until an officer told them to use their bulldozer to plow straight into the water and clear the obstacles as the tide fell. Engineers would first clear the mines so the bulldozer could do its work safely. The plan was to place a line of buoys to guide incoming craft. Once the demolition crews removed the mines, Watson and Wyatt went to work breaking up the obstacles. Soon they had created a driveway for the landing craft. They also helped clear wrecked landing craft along the beach.

Everyone on the beach had to be in full battle gear until D+7. One day a dirt cloud stirred up on the western side of the beach. As it floated toward the Colleville Draw, someone hollered, “Gas! Gas! Gas!” Men scrambled to find their gas masks, which many had discarded shortly after landing. Watson kept his strapped onto the side of his bulldozer. As the cloud approached, he quickly donned his gas mask, but it was a false alarm.

When the bulldozer ran low on gas, Watson drove it up a hill to a refueling station and onto a mat that Army engineers had laid to keep vehicles out of the sand. A military policeman guarding the station yelled at him, “Keep that damn thing off my road!” so Watson tried to maneuver the bulldozer to the side.

Boom! Watson’s tracks detonated a German S-mine, otherwise known as a Bouncing Betty, which, when triggered, launches three feet into the air before exploding. The blast hurtled Watson off his seat and down the hill. Shrapnel lacerated his right leg. Wyatt was also injured. Doctors and medics from a nearby aid station rushed over to the two sailors and helped them in. Once his wounds were treated, he spent the night there.

POWs on the Beach

The next morning Watson awoke feeling much better. He was brewing some hot chocolate outside the station when the Navy lieutenant who promoted him the day before walked up and asked a nearby attending physician, “Can I have Watson?” When the doctor said Watson was only available for limited duty, the officer said, “Hop in my jeep.”

They drove down the draw to the crowded POW holding pen. “There were jillions of them,” Watson recalled of the Germans. His new job was to escort prisoners from the pen to the beach and load them onto any ship or craft he could find. Watson and an Army corporal lined up 300 prisoners, four abreast, and led them in a jeep mounting a .30-caliber machine gun. The prisoners marched with their hands on their heads. As Watson shepherded the Germans to the beach, they asked questions like, “Are you going to put on us on a boat and take us to New York City?” and “You got any cigarettes?”

When the Germans shelled the beach, Watson used a unique alarm system: “German 88mm shells whistle,” he explained. “The German prisoners could hear it before me. If they got down, I got down with them.” Whenever enemy salvos came in, Watson hollered for more guards. “I was worried about the ones who had a chance to escape.”

For about a week, Watson and the corporal marched POWs to the beach, mostly putting them on LSTs. “LSTs were ideal for the job,” said Watson. The center of the ship was just a huge space surrounded by a catwalk. One soldier with a machine gun could guard the prisoners from the catwalk.

While the Germans were, for the most part, docile, American LST officers sometimes were not. One day Watson spotted an empty LST and marched his POWs to the ramp officer, an ensign, and told him, “These prisoners are yours.” The ensign, uncomfortable with a shipload of the enemy, picked up the ship’s phone and yelled, “Give me the bridge! Give me the bridge!” It was no use. Watson marched the prisoners into the hold, the ramp went up, the doors closed, and the captain waited for high tide to raise the ship.

“We Had All the Comforts of Home”

Once Watson’s legs healed, he took on a new job carrying wounded soldiers on stretchers to the beach. “My arms are at least half an inch longer from all the stretcher carrying,” he joked. He and Wyatt improved their sleeping trench by adding mattresses taken from a damaged Landing Craft Infantry (LCI). “We had all the comforts of home.” They also built a cover to keep out the rain. “People were jealous of Dick and I.”

When German aircraft strafed the beach, the two sailors were safe in their trench. During one raid, the LSTs offshore fired 20mm antiaircraft weapons wildly into the air. “And what goes up, must come down,” recalled Watson. Antiaircraft shells rained down, wounding Commander Carusi at the other end of Watson’s trench. Even though he was only 40 feet away, Watson never saw him. “The medics were on him,” he recalled. “All we knew was a man had been hit.” Carusi was put in a jeep and driven to an airstrip above the beach. A C-47 transport flew him to England for treatment.

Ten days after D-Day a brutal storm hit Normandy, beaching ships and destroying an American-built pier. “The storm tore it to hell,” said Watson. He rode out the storm in his covered trench. After the storm, engineers tried to rebuild the pier, but it was now much shorter. Landing craft had to come in closer to deposit their cargoes.

Watson and his fellow beachmasters lived off K and C rations, candy bars, and any other food they could pilfer from the arriving ships. “Nothing went across that beach without us eating it,” he said. “We needed to test everything to make sure the boys got the very best.” Watson was also able to replace his torn-up uniform with new clothes.

Although numerous Army generals and Navy admirals visited Omaha Beach throughout June, Watson never saw any of them. “The only officers I saw were 90-Day Wonders.” Watson and Wyatt once drove a jeep into the city of Bayeux looking for a beer garden. All they found were grateful locals. “They were awfully pleased to see us.” After driving around for about 20 minutes without finding anything, Watson told Wyatt, “Let’s get the hell out of here and get back to the beach.”

Relieved of Duty

Watson received his third wound when a piece of shrapnel tore through his left foot. He made his way to a hospital tent where he took off his boot for the attending nurse. It was filled with blood. She quickly stitched the wound and told him that it was not serious enough to have him admitted, but he should make sure the medics knew so he could receive a Purple Heart medal. After she gave him a new pair of socks, she offered to keep him there for a few days, but he replied, “I want to get back to my unit.”

Watson reported his wound to the medics, but it worried him since he thought that once he was bandaged the Navy would contact his mother and say, “Bobby has been wounded.”

Finally, after 28 days of fighting, taking shrapnel, bulldozing, escorting prisoners, and carrying the wounded, Watson and his platoon were relieved of duty, or as he remembers it, “They told us, ‘We don’t need you here anymore.’” On July 3, he and the five other survivors of his platoon boarded a ship along with a number of German prisoners for the journey back to England.

The beachmasters took up residence in a London hotel across from a pub. Even though they were not heavy drinkers and had no money, they went across the street to celebrate. “Nobody was firing at us anymore!” Watson explained. The locals offered the Yanks a brew called Tobey’s Ale. One pint followed another as the locals celebrated too. “We drank all the Tobey’s Ale left in England.”

The next morning, Watson woke up with a pounding headache and a throbbing right arm. He understood the pain in his head but not his arm, so he rolled up his sleeve to discover a tattoo of an anchor with a ribbon initialed “USN.” He was shocked. “Where the hell did I get this damn tattoo?” he thought, “because I didn’t have any money.” He soon learned that his other beachmasters had the same tattoo. Decades later, Watson returned to the area to see that the hotel was still there, “But there ain’t no tattoo parlor near that place!”

“God Bless Harry Truman”

With his service newly marked on his arm, Watson boarded a ship bound for New York City. He arrived in September at the same pier from which he had departed, Pier 92. He then took a train to Lynn, Massachusetts. There he walked to the movie theater where had worked and presented himself to his old manager, Mr. Collins.

“Where in the hell did you come from?” Collins asked. When Watson told him he needed a ride home, Collins helped him pack his sea bag, mattress, and equipment into his car and they drove off.

They arrived to an empty house. Watson’s mother had become a welding inspector in the Boston shipyard for the war effort, while his father worked in the shoe business. They were both at work, but a quick phone call to his mother got her home early. Upon arriving, she embraced her sailor son, exclaiming, “Good God! It’s really you!” His father came home a little bit later.

But there was still a war on. Watson received orders to report to the Beach Battalion School at Oceanside, California. Since the Navy had no need for more beachmasters, he was given a new job escorting Navy truck convoys with a jeep. They must have heard about his Omaha Beach duties. To make extra money, he filled in as a soda jerk at the PX and drove a cab on weekends.

One day as he worked the counter of the PX someone came in and told him that an American bomber had dropped an atomic bomb on Japan. Watson’s first thought was, “God bless Harry Truman.”

While the day work was routine, the nights were not. Watson and his fellow sailors attended dances whenever they could. One night they rushed to a dance hall to get ahead of a group of Marines. Watson grabbed the hand of a girl on the dance floor and spun her around. Her name was Marjorie Ewing. The encounter changed his life. “I spun her one time, and 68 years later she is still spinning.”

The couple married exactly one year and one day after D-Day, June 7, 1945. They eventually had three boys, Mark, Bob Jr., and Mike.

Reflecting on his war experiences, Watson said, “You go through that one time and that’s enough. I don’t want to do that again.” Yet, he found positives from the experience. “I grew up there.” When asked today if he would have done anything different during his 28 days on Omaha Beach, Watson replied, “I did my best.”

Outstanding tale !

Bravo Zulu