By Allyn Vannoy

During early World War II operations in the Pacific, Geoff Fisken would become one of the most outstanding pilots of the RNZAF—the Royal New Zealand Air Force.

Fisken was born in Gisborne, New Zealand, in 1918, and during the 1930s he learned to fly a de Havilland Gypsy Moth biplane. In 1939, Fisken was working for a farmer in Masterton, and at the outbreak of war in Europe he volunteered for flying duty. Being in a “reserved” occupation, it was not until early 1940 that he was released for service in the RNZAF.

In February 1941, Fisken was posted to Singapore to join No. 205 Squadron RAF which was operating Singapore flying boats manufactured by Short Brothers of Britain. When he arrived, however, he discovered that these machines were being transferred to No. 5 Squadron RNZAF, so Fisken was sent instead to complete a fighter conversion course using Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Wirraway trainers and Brewster Buffaloes. Upon completion of this course, he was posted to No. 67 Squadron RAF, which was primarily made up of fellow New Zealanders.

In October 1941, as the threat of war with Japan was increasing, No. 67 Squadron was moved to Mingaladon, Burma, but Fisken was posted instead to No. 243 Squadron RAF.

With the Japanese attacks across East Asia and the western Pacific on December 8, 1941, No. 243 Squadron was assigned to defend the Royal Navy’s Force Z––the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse. Two days later the British warships were attacked and sunk by Japanese air units. Then, as the Japanese advanced down the Malay Peninsula, Singapore became the target of an increasing number of bombing raids.

On December 16, while operating in defense of Singapore, Fisken claimed a Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter shot down. A fortnight later, on December 29, he claimed two Japanese bombers, and on January 12, 1942, Fisken downed a Nakajima Ki-27 Nate fighter. Then, two days later, he downed another Zero, being lucky enough to land his disabled aircraft after being caught in the explosion of the Japanese plane.

On January 17 he shot down or assisted in the destruction of three Mitsubishi G3M Nell bombers, and four days later he brought down another enemy fighter. Amazingly, all of these actions were while Fisken was flying an obsolescent Brewster Buffalo.

By this time No. 243 Squadron had lost the majority of its pilots and virtually all its aircraft. As a result, it was merged with No. 453 Squadron of the RAAF, which continued to operate along with No. 488 Squadron RNZAF.

Fisken claimed another fighter destroyed on February 1. Five days later he was bounced by two Japanese fighters, shooting down one while narrowly escaping the other, though he was injured in the arm and leg by a cannon shell.

On the eve of Singapore’s surrender, Commonwealth pilots were withdrawn to Batavia (now Jakarta), Java, and later to Australia. As a result of his performance in Singapore, Geoff Fisken received a commission and was promoted to the rank of pilot officer.

Fisken was just one of hundreds of New Zealanders––Kiwis––who loved nothing more than a good brawl but of whom little is known today outside their island nation.

Long Road

The Kiwi pilots had traveled a long road to become part of the Pacific War, but they would labor in relative anonymity.

When Great Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, the Royal New Zealand Air Force’s strength was only 1,160 personnel with a mere 102 aircraft, mostly secondhand Blackburn B-5 Baffins and Fairey Gordons, both biplanes, along with some relatively newer but still obsolescent aircraft—five low-wing, two-engine Airspeed Oxfords and nine Vickers Vildebeest biplanes that were totally outclassed by Japanese aircraft. The role of the RNZAF then was purely as a training organization that supplied pilots to the Royal Air Force (RAF).

During the first 12 months of the war, the RNZAF undertook efforts to transition from a training organization to a combat force––initially arming all available machines, including airliners, and endeavoring to reequip with more modern machines. The period saw an expansion of the RNZAF with new pilot training schools established at Taieri, Harewood, New Plymouth, and Whenuapai, and an air gunner and observer school at Ohakea.

The possible presence of German surface raiders in the Pacific led to the formation of units flying Vildebeest biplane torpedo bombers, organized into three territorial squadrons to patrol off Auckland, Wellington, and Lyttelton.

Early in 1941, the RNZAF obtained Lockheed Hudsons, American-built, two-engine light bombers, to be used for maritime patrol and reconnaissance operations. At about the same time, the RNZAF’s No. 5 Squadron, equipped with obsolete Vickers Vincents biplanes and four worn-out Singapore flying boats, was sent to the British colony of Fiji to conduct patrols and reconnaissance.

On December 8, 1941, the RNZAF had 641 aircraft, the majority used for training. Its combat aircraft included 36 Lockheed Hudsons, 48 Vickers Vincents, 26 Vickers Vildebeests, and two Short Singapore III flying boats. The RNZAF’s strength had grown to 17,000 personnel, with 10,500 in New Zealand, 1,100 in Canada, some 3,600 attached to the Royal Air Force, and nearly 600 at other Pacific locations, mainly on Fiji.

To offset its own meager resources, New Zealand received some assistance from Britain, but most of the aircraft initially provided consisted of trainers, including North American Harvards (designated the AT-6 by the U.S. Army Air Corps and the SNJ by the U.S. Navy), Hawker Hinds (light biplane bombers), and de Havilland DH 82 Tiger Moth biplanes. These aircraft were repainted for combat operations and armed.

In late March 1942, the RNZAF formed the surviving pilots from operations at Singapore––Nos. 243 and 488 Squadrons––into No. 14 Squadron RNZAF under Squadron Leader J.N. Mackenzie. Employed in a defensive role, they were initially equipped with obsolete Harvards.

As few combat-capable aircraft were yet available, New Zealand turned to the United States for assistance.

A great deal of discussion took place between New Zealand, Britain, and the United States on the question of equipment for the RNZAF and the role the RNZAF was to play in the Pacific Theater. The New Zealand government, under Prime Minister Peter Fraser, proposed that the RNZAF be expanded to a strength of 20 squadrons by April 1943 and that a proportion of the squadrons should take part in offensive operations against the Japanese. The proposal was submitted to the joint planning staffs in Britain and the United States for consideration.

In view of the overall supply position, and the fact that the expansion and equipping of the RNZAF would necessitate the supply of considerably more than just fighter aircraft, the American joint planners recommended to their chiefs of staff that the RNZAF should be limited until April 1943 to a strength of four light bomber squadrons with Hudsons and five fighter squadrons with Curtiss P-40s. The British chiefs of staff recommended a further six squadrons with 64 North American B-25 bombers and 48 fighters.

On September 3, 1942, a “Lend-Lease” agreement was signed by the United States and New Zealand. In time, the program provided 297 P-40s to the RNZAF. The aircraft were designated Kittyhawks, but later models subsequent to the P-40K were given the American designation Warhawk. The RNZAF flew a mixture of both models and generally referred to them all as Kittyhawks.

These aircraft were used to equip six squadrons—Nos. 14 through 20; later, the number of RNZAF fighter squadrons operating in the Pacific would increase to 13 (No. 14 through 26). The P-40s, and later Vought F4U Corsairs, were the backbone of the RNZAF.

By June 1942, the RNZAF had only eight operational squadrons—six in New Zealand and two in Fiji.

The first RNZAF squadron to engage the Japanese in combat in the Southwest Pacific was No. 3 BR (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron, as a detachment of six Hudsons arrived at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal in November 1942. The squadron was tasked with performing reconnaissance duties and scouting for Japanese shipping attempting to deliver troops and supplies to Guadalcanal.

The RNZAF Hudsons flew four to six patrols daily over New Georgia, Santa Isabel, Choiseul, and the surrounding waters. While essentially a reconnaissance aircraft, the Hudson could carry a bomb load of four 500-pounders. American and RNZAF aircraft carried out regular patrols by day and night seeking enemy convoys in the Slot—the north-south channel between the New Georgia group and Choiseul and Santa Isabel Islands.

The arrival of No. 3 BR Squadron filled an important gap in the types of aircraft available in the Solomons and was heartily welcomed by the overworked aircrews of American Air Group 14. Prior to the arrival of the New Zealand squadron, the Americans had been using torpedo and dive bombers for reconnaissance work, supplemented by long-distance patrols with heavy bombers. The Hudsons, with their longer range, relieved the dive bombers and at the same time released the long-range bombers from much of their reconnaissance work.

Just a day after arriving, on his first flight from Henderson Field, Hudson Pilot Flying Officer George E. Gudsell and his crew spotted a Japanese tanker and two transports being escorted by a destroyer near Vella Lavella, northwest of Guadalcanal. As they approached, the ships’ gunners commenced firing at his Hudson. Three Japanese Nakajima floatplanes then attacked Gudsell’s aircraft. By skilfully maneuvering the Hudson at altitudes as low as 50 feet, Gudsell managed to evade the fighters and returned safely to Henderson.

Three days later, when shadowing another convoy, Gudsell’s aircraft was attacked by three Zeros. In a 17-minute duel, again at very altitude, the Hudson was hit several times, but none of the crew was injured as Gudsell again managed to safely return to Henderson. For these actions, Gudsell was awarded the U.S. Air Medal, the first member of the RNZAF to be awarded a decoration in the Southwest Pacific. Amazingly, Gudsell’s Hudson, NZ2049, involved in both of the November 1942 actions, exists today in the aircraft collection of John Smith of Mapua, New Zealand.

Aircraft of No. 3 BR Squadron not only flew routine patrols but occasionally were used for special missions. On January 8, 1943, a Hudson bombed the village of Boe Boe on southern Bougainville. The natives had been supporting the Japanese against the Allies’ coastwatcher, and the strike was intended to frighten them and bring them under the coastwatcher’s control. The aircraft bombed the village just before dawn, and the coastwatcher later signaled his thanks.

The Kiwi personnel based at Henderson shared the same hardships as Guadalcanal’s other defenders. The most urgent need for the Kiwis was providing dugouts to give squadron personnel protection from nightly air raids. This was achieved by digging a tunnel in a ridge close to the squadron’s camp. The New Zealanders lived in tents in a jungle gully, where rain, mosquitoes, and mud made life miserable until a new camp could be built on a nearby ridge.

After their failure to recapture Guadalcanal in 1942, the Japanese undertook no further offensive operations in the Solomons. Instead, they concentrated on developing their forward bases at Munda, Vila, and Rekata Bay and building up the Buin-Kahili area in southern Bougainville into their major base in the Solomons, while establishing outposts on Vella Lavella, Choiseul, and Shortland.

The last two months of their campaign on Guadalcanal had been a delaying action to cover the development of these areas. They also brought in army reinforcements to Bougainville and occupied most of the island. The increasing effectiveness of the Allied air attacks on shipping forced the Japanese to give up the use of ships south of Bougainville, replacing them with barges for resupply operations.

RNZAF Build Up

In the months that followed the Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal, the main concern of the American command in the South Pacific was building sufficient forces to carry out operations against the northern Solomons and New Britain. During this period the strength of the RNZAF was increased by the arrival of additional squadrons.

In 1943, the RNZAF began to flex its new muscle, transforming itself into an offensive force as it was deployed to forward bases. A squadron of Kittyhawks, No. 15, which was established in 1942 under Squadron Leader A. Crighton, arrived on Guadalcanal in April 1943 and would go on to fly more sorties than any other RNZAF fighter squadron in the Pacific, seeing service at Tonga, Guadalcanal, New Georgia, Espiritu Santo, Bougainville, and Green Island.

The first operations conducted by No. 15 Squadron, beginning on April 29, were local patrols followed by flights in early May providing cover for American naval forces and escorting American bombers attacking Japanese air bases at Munda and Rekata Bay and barge concentration areas at Kolombangara. The squadron’s first contact with enemy aircraft occurred on May 6, when two RNZAF Kittyhawks escorting a patrolling Hudson shot down a Japanese floatplane.

Also during April, another RNZAF squadron, No. 14, was posted to Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides. The squadron then moved to Guadalcanal on June 11, and the next day, in its first combat, shot down six enemy aircraft, of which two Zeros were credited to Geoff Fisken of Singapore fame. On July 4, while patrolling over Rendova in his P-40 nicknamed Wairarapa Wildcat, Fisken scored his final victories, destroying two Zeros and a Mitsubishi G4M Betty twin-engine bomber.

Although Fisken’s air victories in the Solomons were well documented, his kills and probables at Singapore were contested, reducing the number of his wartime victories from 13 to 10. Nevertheless, he was reputed to be the highest scoring Commonwealth ace in the Pacific Theater. In September 1943, Fisken would receive the Empire’s Distinguished Flying Cross; however, due to complications from injuries received at Singapore he would be medically discharged from the RNZAF in December 1943.

American experience had shown, particularly with regard to fighter squadrons, that aircrews should remain in a combat area only for a short time if they were to remain effective. The RNZAF decided to follow the American practice, giving its crews six-week-long tours of duty. At the end of a tour they returned to New Zealand for leave and training.

At 9:30 am on May 8, 1943, 19 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers and three Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers of the U.S. Marine Corps, escorted by 32 RNZAF F4U Corsairs along with eight Curtiss P-40 Warhawks of No. 15 Squadron, took off from Guadalcanal to search for Japanese warships and transports reported in Blackett Strait, the waterway in the western province of the Solomon Islands.

The TBFs and F4Us turned back due to weather, but the SBDs and the P-40s continued on and made contact with enemy destroyers near Gizo Anchorage. The Kiwi pilots, led by Squadron Leader M.J. Herrick, attacked in two sections of four, flying line abreast.

In the face of heavy gunfire as they approached a Japanese destroyer that was run aground, the P-40s made their attack just feet above the water, then leapfrogged over the destroyer and returned to wave-top level on the other side.

As the second section made its strafing run, the SBDs dove on the ship and scored a hit with a 1,000-pounder, setting it alight. The New Zealand fighter pilots then continued on to attack Japanese landing craft that were in the process of putting troops ashore on a nearby island, inflicting heavy casualties.

Main Offensive

By the middle of 1943, the Allies had amassed sufficient matériel and men in the South Pacific to launch an offensive against Japanese positions in the central Solomons. The first objective was the airfield at Munda on New Georgia.

The role of the Allied air forces in support of the land and naval operations was to carry out reconnaissance throughout the Solomons and as far north as Buka and New Ireland to give maximum air cover and support to the land forces, check Japanese air operations from New Georgia and southern Bougainville, and destroy Japanese naval units threatening Allied forces in either the South or Southwest Pacific.

At the end of June, the Allied air forces had established two forward base complexes for operations against New Georgia at Guadalcanal with four airfields and in the Russells with two airstrips.

The main Japanese bases in the area included Kahili, with 70 to 100 aircraft; Ballale, which had a small number of planes, mainly bombers; Buka, used primarily as a staging base for moving between Rabaul and Kahili; and Rabaul, where the main air reserves were stationed.

On the morning of July 1, the Japanese launched dive bombers and fighters to attack American positions on the island of Rendova but were intercepted by Allied fighters, including eight P-40s from No. 14 Squadron. In the resulting action, 22 Japanese aircraft were shot down against the loss of eight Allied fighters; No. 14 Squadron claimed seven aircraft destroyed and three probables. Two New Zealand aircraft were lost with one pilot rescued.

On July 25, No. 14 Squadron was rotated out of Guadalcanal. During its tour, the Kiwi pilots had destroyed 22 Japanese aircraft with another four probable, with the loss of four aircraft and three pilots.

On September 3, eight fighters of No. 16 Squadron provided bottom cover to a force of Consolidated B-24 Liberators bombing Kahili. On the way home, two Kiwi pilots dropped back to cover a damaged B-24, which was under attack by eight to 10 Zeros. They were successful in driving off the attackers and escorted the bomber safely back to base. For their efforts, both pilots, Flight Lieutenant M.T. Vanderpump and Flight Sergeant J.E. Miller, received the American Distinguished Flying Cross, the first awarding of the decoration made to RNZAF personnel.

The Allied capture of Munda on August 5 drove a wedge into the Japanese screen of defensive outposts south of Bougainville. This brought Allied forces to within 120 miles of Japanese air bases at Kahili and Ballale, while they continued to maintain considerable air forces in the Bismarcks and Solomons. During the previous few weeks the Japanese had suffered such losses that they were forced to husband their strength to protect their bases on Bougainville and New Britain.

On October 1, American ships lying off Vella Lavella, carrying troops of the 3rd New Zealand Division, were attacked by Japanese dive bombers and fighters. Eight Kittyhawks of No. 15 Squadron in company with 12 U.S. Marine F4U Corsairs intercepted the third of three attacks; the New Zealanders accounted for seven enemy dive bombers.

From October 12, 1943, as part of Operation Cartwheel, RNZAF aircraft became an integral part of the Allied air campaign while operating under U.S. Navy direction. Cartwheel was a twin-axis operation aimed at neutralizing the Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain with advances along the northeast coast of New Guinea by forces under General Douglas MacArthur, while other Allied units under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz advanced through the Solomon Islands toward Bougainville.

Final Stages

The elimination of the Japanese positions in the central Solomons opened the way for the final stage of the campaign, designed to secure bases from which Rabaul could be attacked. The operation took the form of a landing at Cape Torokina, north of Empress Augusta Bay and halfway up the western shore of Bougainville, by the 3rd Marine Division on November 1. Two days after the landing, naval construction battalions began building an airstrip on Cape Torokina, which was ready for use on November 24.

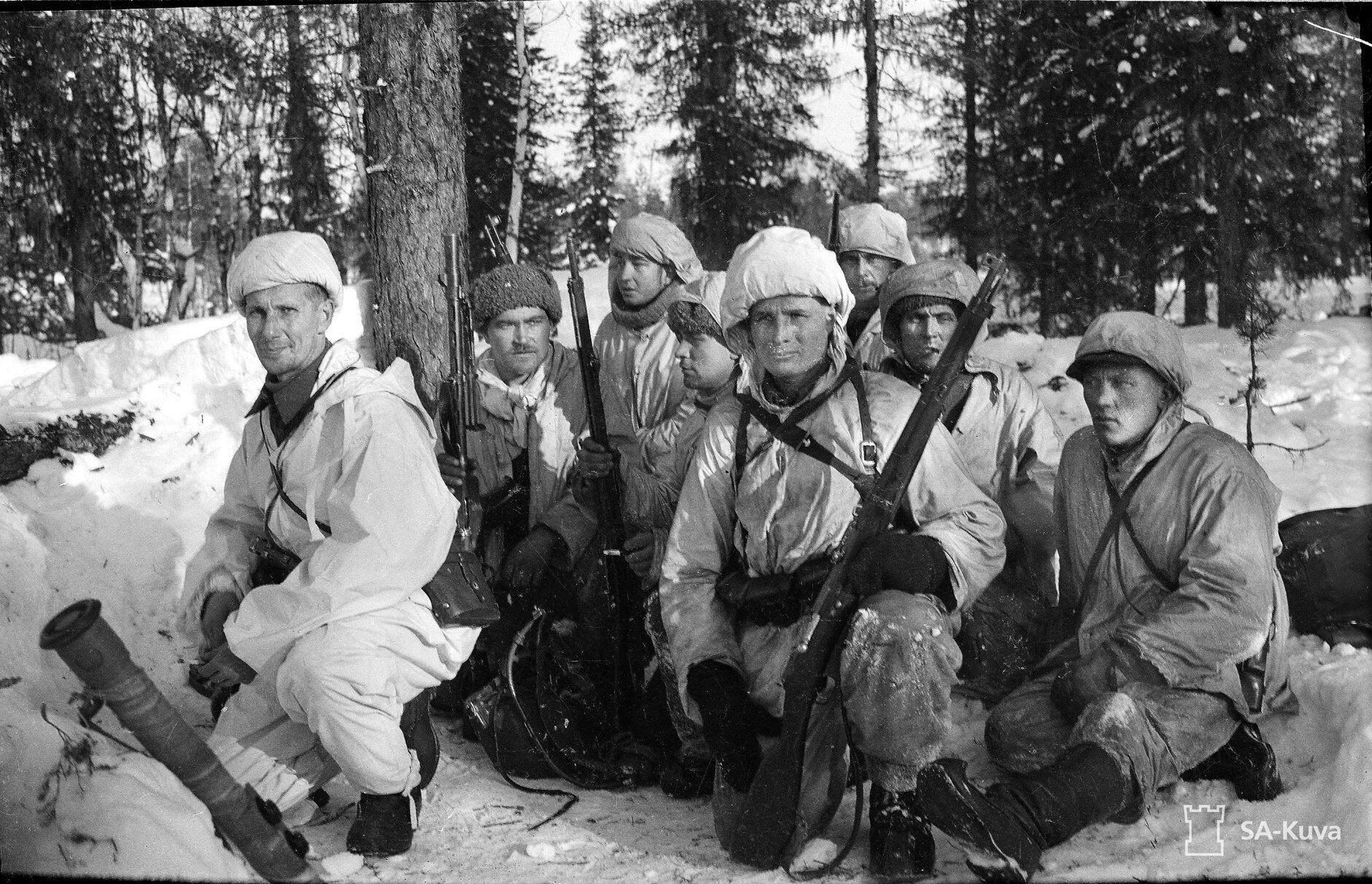

The New Zealand Fighter Wing was established at Ondonga, New Georgia, and flew over 1,000 sorties in November during the Bougainville fighting. Despite fatigue, difficult operating conditions, heat, rain, mud, and nights interrupted by Japanese air raids, the morale of the unit remained exceptionally high.

The RNZAF official news service reported that on November 22 four New Zealand P-40s encountered a large group of Japanese Zeros over Bougainville. Led by Flight Lieutenant R.H. Balfour, the section was patrolling in the area of Empress Augusta Bay at 24,000 feet when 35 to 40 Zeroes approached. Diving into the Japanese, Balfour exploded two of the enemy planes with machine-gun fire. He and his fellow Kiwis shot down five Zeros, damaged at least six others, and chased the remainder off, all without loss.

Squadron activities developed into daily routines. The squadron’s workday began before dawn as pilots prepared for morning patrols over Ondonga or flights to Cape Torokina. After a quick breakfast, the pilots received a final briefing at the operations room, which included the latest mission information from the intelligence officer and the meteorological officer. Servicing and repair parties had worked through the night, often interrupted by air raids and heavy rain, preparing planes for the day’s missions.

Two hours after the first pilots had left, another flight was ready to take off to patrol over the Torokina beachhead, strafe Japanese targets, or to accompany an American bombing raid. At mid-morning the first sorties returned, and the planes were serviced for the next operation.

In the afternoon, flights took off for Bougainville to patrol over the Allied positions. Other assignments included escorting air-sea rescue Consolidated PBY Catalinas or Douglas Dakotas hauling supplies to Torokina or giving fighter protection to Allied shipping between Guadalcanal and Bougainville. The last patrols came in at dusk.

The construction of airstrips on Bougainville made it possible for land-based fighters equipped with long-range fuel tanks to operate against Rabaul, both on offensive sweeps and as bomber escorts. The first fighter sweep was made by 80 aircraft, which included 24 from the New Zealand Fighter Wing, on December 17, 1943.

Originally, the American fighter command had planned not to use P-40s over Rabaul, as they were considered second-rate fighters; however, the Kiwis soon proved themselves and the P40s, and they were used in all subsequent operations.

On December 24, the New Zealand Wing in conjunction with 24 American fighters made a sweep over Rabaul. The force approached the target area in a formation of tiers, with the New Zealand squadron forming the two bottom tiers.

Ten miles northeast of the town, some 40 Japanese fighters came climbing up to intercept, but the New Zealand squadrons each selected a group and dived to attack. This broke up the Japanese formations and resulted in a series of dogfights. Twelve Japanese aircraft were shot down, with four more claimed as probables and a number of others damaged, for the loss of five New Zealand pilots.

Flying Close Cover

Since the P-40s could not operate efficiently above 20,000 feet, they acted as low cover when escorting bombers, flying at 18,000 feet. Above them American Grumman F6F Hellcats, Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, or Corsairs provided medium and high cover.

The role of close cover meant staying with the bombers and dealing with any enemy fighters that had succeeded in piercing the other layers of the escort. It demanded a high level of flying discipline and resistance to the temptation of being drawn into combat elsewhere. The New Zealanders were particularly popular with American bomber crews because they stuck to their close support assignments.

By early 1944, New Zealand Fighter Wing pilots flying P-40s over the Solomons and Bismarcks had racked up 99 confirmed kills and 14 probables. The list included 80 Zeros shot down plus 11 probables, five Hamps downed along with two probables, 11 Vals shot down, one Betty, one Dave, a Tony probable, and one unknown type shot down.

The shootdowns were made by 61 individual Kiwi pilots and included two aces––the indomitable Flight Officer Geoff Fisken and Squadron Leader P.G.H. Newton. Twenty P-40s were lost to enemy action with another 152 to accidents; 67 pilots lost their lives. Additionally, four Japanese aircraft were destroyed by RNZAF Venturas and Hudsons of No. 1 and 3 Squadrons, respectively.

During 1944, RNZAF fighter squadrons were reequipped with Corsairs. The first such squadron, No. 20, arrived at Bougainville on May 14.

There were several advantages to changing to the Corsairs. First, the model was already in use in the Pacific by the U.S. Marines. Because the P-40 was powered by a straight-block V12 Allison engine, one bullet could put the cooling system out of action, and the loss of one cylinder would throw the crankshaft out of balance, resulting in bearing failure. These problems did not exist with radial engines as used in the Corsair. Such engines could still perform satisfactorily even with a cylinder shot out. Second, the Corsair was faster than the P-40 and was extremely stable in flight. Third, the Corsair’s endurance allowed it to fly for almost 13 hours with a full internal fuel load.

While the RNZAF Fighter Wing was operating from Ondonga, New Zealand bomber and reconnaissance aircraft continued to carry out patrols and searches, first from Guadalcanal and later from Munda. These squadrons were reequipped with Lockheed PV1 Venturas, replacing the obsolete Hudsons. The Ventura was a twin-engine bomber and reconnaissance aircraft with a maximum speed of over 300 miles per hour and a cruising range of over 2,000 miles. The Ventura was also more versatile than the Hudson and had greater offensive power.

Bombing and strafing missions along the coast of Bougainville were a regular feature of the Ventura squadrons’ work. Formations of up to six aircraft, sometimes accompanied by fighters, attacked enemy barges, encampments, and troop concentrations. Bombing was usually done from a few hundred feet, after which the aircraft strafed the target. The normal bombload for each aircraft was six 500-pound bombs, with fuses set to provide just enough delay for the aircraft, flying at low levels, to escape the blasts.

With almost daily attacks on Rabaul, Venturas were also detailed to follow the strike force and search for pilots who might have been shot down or had bailed out into the sea. If a downed airman were found, the Ventura crews signaled for a Catalina to conduct a rescue and, when possible, remained over the spot until the Catalina arrived.

As these survivor patrols followed the striking forces close to Rabaul, where they were liable to encounter Japanese fighters, aircraft were sent in pairs for mutual protection.

On one such raid, a Ventura cruising over the mouth of St. George’s Channel, just beyond Rabaul, was attacked by six to nine Zeros and a running fight ensued. Skillful piloting combined with efficient fire control and accurate gunnery resulted in three Japanese planes being shot down and two others possibly destroyed, while the Ventura, although extensively damaged, made it safely back to base.

Other operations carried out by the Venturas included minelaying by night in Buka Passage, searching for submarines, and dropping supplies to coastwatchers.

Part of the strategy of cutting off Rabaul was the securing of Green Island north of Bougainville. A coral atoll, its chief islet, Nissan, was determined to be suitable for the construction of airfields. It would provide a base midway between Cape Torokina and Rabaul.

New Zealand infantry landed on Green Island on February 15, 1944. Construction battalions followed immediately, so that by March 7 a fighter strip was ready for operations and a bomber strip was well advanced. The use of Green Island allowed fighters to reach Rabaul without carrying long-range fuel tanks.

On February 29, troops of General MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Command landed on Los Negros in the Admiralty Group northwest of Rabaul and across the Bismarck Sea. This was followed on March 20 by the 4th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division, occupying Emirau, north of New Ireland. These landings completed the encirclement of Rabaul, cutting off 50,000 Japanese on New Britain and New Ireland and another 30,000 on Bougainville and Choiseul.

At the beginning of 1944, the Japanese suffered heavy aircraft losses––126 in January and another 58 in the first half of February. They concluded that it was no longer possible to maintain air cover over Rabaul and withdrew the shattered remnants of their squadrons. Of the 700 Imperial Japanese Navy and 300 Army aircraft that had been flown into Rabaul during 1942 and 1943, only 70 remained in February.

The last engagement between the RNZAF and Japanese fighters occurred on February 13, when aircraft of No. 18 Squadron were escorting American TBFs on a bombing raid against Vunakanau, a major airfield of the Rabaul complex. The raid was met by 25 Zeros. Two were shot down with the loss of one P-40. These were the last two recorded kills made by New Zealand fighter pilots in the Pacific. But the RNZAF was far from finished.

Change in Roles

With no enemy air opposition, the RNZAF’s new Corsairs were switched from a fighter escort role to fighter bomber operations. One Dauntless and two Avenger squadrons added their weight to bombing operations from airfields on Bougainville. No. 6 Flying Boat Squadron operated over the area carrying out maritime reconnaissance and rescue missions using Catalinas, while bomber and reconnaissance squadrons equipped with Venturas conducted raids on Japanese positions in the northern Solomons.

Although the threat posed by Japanese aircraft had virtually disappeared, combat operations were nonetheless perilous. In one incident, Flight Sergeant “Rip” Reiper was flying with a section of four Corsairs that had set out from Bougainville to bomb a target at Rabaul. Reiper was in the number four position in the section as it flew for about an hour through clouds in a tight formation.

Over Rabaul the flight leader made a sudden turn. The number two aircraft, on the leader’s left, apparently became disoriented during the turn and collided with the leader. Both aircraft exploded, the impact of which caused the number three aircraft to also explode, leaving the young and frightened Reiper to find his way back to Bougainville alone.

Whenever strikes were flown against Rabaul, a Catalina with fighter escort was sent to patrol south of New Ireland to pick up any downed pilots; RNZAF crews were able to rescue 28 men from the sea between Bougainville and the Gazelle Peninsula.

As the South Pacific campaign appeared to be drawing to a close, the future of the RNZAF became the subject of considerable discussion between New Zealand and American authorities. As early as March 1944, it was felt that without any further Japanese fighter opposition there was no point in continuing to send fighter squadrons to the forward area; however, it was felt that it would be bad for morale if trained, operational units were kept in New Zealand doing nothing. So, it was decided to continue sending the squadrons forward in rotation even if they could only be employed as fighter bombers.

In April the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington weighed the future role of the RNZAF. Consideration was given to restricting it to a few bomber and reconnaissance and flying boat squadrons for garrison duties in the South Pacific, which meant that all fighter squadrons would be scrapped and that the RNZAF would no longer be given a combat role. It was felt that this would have had a twofold effect.

Domestically it would have meant that the size of the RNZAF could be reduced, releasing men to meet the acute shortage of manpower in industry and agriculture; but the millions of man hours and the immense amount of money that had been spent in training and equipping the squadrons would be wasted. Also, if New Zealand dropped out of the Pacific War before it was finished, it might reduce that nation’s role in the post-war councils.

Taking these factors into consideration, the RNZAF was not satisfied at being relegated to a secondary role. The New Zealand minister in Washington was instructed to press the point and try to have the RNZAF included in any active theater where it might be of use.

Three options were considered. First, the squadrons might continue to operate under U.S. Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey’s command in the Central Pacific. This would mean continuing to work in a command with which they were familiar along with minimal supply problems since they were already equipped with U.S. Navy-type aircraft. Second, they might be transferred to the British Southeast Asia Command. But this meant sending them to India and reequipping them with British-made aircraft.

Finally, they might be transferred to General MacArthur’s command in the Southwest Pacific. This would mean that, as part of an Army command, they would have difficulty getting appropriate supplies of aircraft and spares.

In the meantime, early in May 1944, U.S. Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, while not committing himself as to the future role of the RNZAF, agreed that the Kiwi squadrons should continue offensive operations in the northern Solomons.

The program called for 11 squadrons to carry out garrison duties in the Solomons area. The U.S. Navy was to provide four squadrons and the RNZAF seven—four fighter, two medium bomber, and one flying boat.

Two New Zealand fighter squadrons were to be stationed at Espiritu Santo and two at Guadalcanal; one bomber-reconnaissance squadron was to be stationed at Guadalcanal and the other at Fiji; and the flying boat squadron was to be based at Halavo Bay, Florida Island.

In addition, New Zealand squadrons to be transferred to the Southwest Pacific Area would include another four fighter, two medium bomber, and one flying boat. One fighter squadron was to remain at Bougainville while another was to be moved to Los Negros. The other two were to be assigned to Emirau and Green Island. New Zealand bomber-reconnaissance squadrons were also located at the latter two bases.

While these arrangements were being worked out, fighting continued in the Solomons and over New Britain.

Grueling Fight

In the final months of the Pacific War, fighting took on a grueling nature for the crews of the RNZAF. From October through December 1944, American ground units were gradually withdrawn from the Solomons-Bismarcks area for operations in the Philippines, their place being taken by Australian forces.

Also, early in December 1944, the RNZAF Venturas had begun to take part in “night heckles” over Rabaul, which had previously been done exclusively by American PBJs (the U.S. Navy/Marine Corps version of the B-25 medium bomber), assisted sometimes by “Black Cats” (PBYs). It was part of the Allied effort to make life for the Japanese as uncomfortable as possible by keeping one or more aircraft constantly over Rabaul during the night, each carrying bombs that could be dropped anywhere at any time during the patrol.

Under the Australians, the campaign on Bougainville assumed a new character. For the Americans, the island had not been an objective in itself but a stepping stone in the advance northward, and their operations were limited to ensuring the integrity of the Empress Augusta Bay base.

The task of the 2nd Australian Corps, on the other hand, was to retake the island from the 22,000 Japanese troops who still occupied a large part of it. It was in support of these operations that New Zealand aircraft flew eight to 46 sorties daily in addition to the continuous pounding of Rabaul and New Ireland.

The bombing line on Bougainville was only 30 miles south of Cape Torokina. Strikes were routinely close support bombing runs to assist the Australians in their advance toward the south end of the island. The bombs were usually either 1,000-pound high explosive or depth charges. The latter were almost entirely explosive with little metal casing.

Both types were fitted with a detonator mounted on the end of a 21/2-foot rod protruding from the bomb. Called daisy cutters, they were designed to explode slightly above ground level to clear the jungle without digging too deep a hole that would hamper an advance.

Dark Days

The brutal nature of the Pacific War was exemplified when a Kiwi pilot was shot down during a bombing raid on Japanese positions on Bougainville. The bombing was in support of Australian troops, and after the pilot bailed out the Australians made a dash toward where he would have landed. When they reached the scene, the pilot was found to still be alive, strung up to a tree by his thumbs, but with his stomach slit open and his intestines spilling out.

Another dark day for the RNZAF came on January 15, 1945. During a strike on Toboi Wharf in Simpson Harbor at Rabaul, conducted by aircraft of Nos. 14 and 16 Squadrons flying from Green Island and No. 24 from Bougainville––a total of 36 Corsairs––one was knocked down by antiaircraft fire. The F4U was piloted by Flight Lieutenant Francis George Keefe of No. 14 Squadron, who managed to bail out, landing in the harbor.

An exceptional swimmer, Keefe struck out for the harbor entrance. For some time he made good progress. Then, in the middle of the afternoon, by which time he had been swimming for six hours, the tide and wind changed and he began to drift back up the harbor.

A rescue force had been quickly organized while sections of Corsairs kept watch overhead to prevent Japanese attempts to capture Keefe. Two bamboo rafts were assembled and loaded aboard a Ventura at Green Island, intended to be dropped to the downed pilot.

As two Corsairs orbited above Rabaul awaiting the arrival of the Ventura, an American Catalina pilot circling just beyond the harbor entrance spotted Keefe and twice requested permission to land and pick him up. The request was denied both times by the officer in charge, Squadron Leader Paul Green, the commander of No. 16 Squadron, due to the threat posed by Japanese coastal and antiaircraft guns.

When the Ventura arrived, it was accompanied by another 12 Corsairs, whose task was to strafe the Rabaul waterfront while the Ventura dropped the rafts. Everything went as planned, but Keefe failed or was unable to reach the rafts. The rescue was then aborted, and all aircraft were directed to return to base.

Approximately halfway back to Green Island, the Corsairs encountered a tropical storm front stretching across the horizon and down to sea level. Due to limited navigation aids, the aircraft were required to maintain a tight formation as the storm and darkness reduced visibility. The pilots could only see the navigation lights of the other aircraft in their flight.

Five of the Corsairs crashed into the sea, one crashed at Green Island as it was making its landing approach, and a seventh simply disappeared. The lost pilots included Flight Lieutenant B.S. Hay, Flight Officer A.N. Saward, Flight Sergeant I.J. Munro, and Flight Sergeant J.S. McArthur from No. 14 Squadron and Flight Lieutenant T.R.F. Johnson, Flight Officer G. Randell, and Flight Sergeant R.W. Albrecht from No. 16 Squadron.

After the war, it was reported by Japanese troops captured at Rabaul that Keefe had managed to swim ashore. With a wounded arm, he was taken prisoner and died a few days later.

One of the pilots involved in the operation, Flight Sergeant Bryan Cox, suffered a failure of both his radio and lights during the return flight but happened to stumble upon the landing strip at Green Island just as he was nearly out of fuel. It was not only a fortunate day for him, but also his 20th birthday.

Winding Down

From January through August 1945, 10,592 sorties were flown by the RNZAF against Japanese positions on Bougainville and Buka, with 4,256 tons of bombs dropped.

Agreement was finally reached between the U.S. and Australian governments for the RNZAF to take part in operations in Borneo with the Australians and in the Philippines supporting U.S. forces.

But both of these commands were using U.S. Army Air Forces combat aircraft, so the RNZAF would need to be reequipped. North American P-51D Mustang fighters had been ordered to form new fighter squadrons, and while 30 were delivered out of some 320 ordered to replace F4Us, the war ended before they could be brought into active service.

Of the 424 F4Us supplied to the RNZAF during the war, a total of 154 RNZAF Corsairs were written off due to accidents and 17 to enemy action, with 56 pilots killed or missing and one dead as a POW. Forty-two Ventura bombers were also lost in combat and accidents during the war.

At its peak, the RNZAF in the Pacific had 13 squadrons of Corsair fighters, six of Venturas, two each of Catalinas and Avengers, two of C-47 Dakota transport/cargo aircraft, one of Dauntless dive bombers, along with mixed transport and communications aircraft, a flight of Sunderland flying boats, and nearly 1,000 training aircraft of various types.

From September 3, 1939, to August 15, 1945, a total of 3,687 RNZAF personnel died in service, the majority with RAF Bomber Command flying in Britain and over Europe. The RNZAF had grown from a small prewar force to over 41,000 men and women (WAAFs) by 1945, including just over 10,000 serving with the RAF in Europe and Africa; 24 RNZAF squadrons saw service in the Pacific. On VJ Day, the RNZAF had more than 7,000 of its personnel stationed throughout the Solomons and Bismarcks.

The Kiwi airmen had not only fought proudly against their Japanese foes, but also carved out a place for themselves among their much larger Allies—Britain, Australia, and the United States—as they wrote their names into the history of the Pacific air war.

There is a famous photo by Horace Bristol of a PBY Gunner, taken at Rabaul Harbor 1944. He had jumped in to save a shot down pilot and then returned to his post, minus clothes. Nobody knows who he was but as he served on a PBY Catalina in 1944 one would assume he was Australian or from New Zealand and was obviously very brave. I was born in 1956 so I wasn’t around at the time but I find myself needing to know if he survived the war as so many were shot down. I wondered if his brave deed was reported anywhere so he could be traced and a name out to the photo

I can wholeheartedly endorse Vannoy’s comment on the USAAF crews regard for the Kiwis.

In the early 1970s, I met a ex-USAAF P38 pilot at the Reno Air Races, hearing my Father had flown with B-25s out of Henderson & Bomber Field #2 on “the ‘Canal”, he passed me his business card to give my Father. A year later, my parents came for a visit & the card was passed along. Father heard my story, read the card, and tossed it in a waste basket. …I inquired…

“P-38 jockey? Those Air Force hotshots flying top cover for us would fly weaving patterns over us for a while… Then, a seagull or two would appear on a distant horizon and they’d peel off and disappear in twos to give chase. It was those Aussies and Kiwis, flying obsolete old fighters, that keep close formations over us and maintained discipline in protection.”

PS- Father volunteered for a mission 18Feb1944 over Buka Island. They were testing the first 75mm equipped B-25H in the 42nd BG, 13thAAF strafing a Japanese plantation on Buka. Ground fire set a engine on fire and they ditched off Cape Hanpan. Father pushed an unconscious Gunner-Engineer out of the submerged bomber’s side escape hatch & got him in a life raft with a deceased crewman. Pilot, Observer, and Cannoneer went down and have never been recovered.

They were rescued by a PBY5 Dumbo mission of No. 6 (Flying Boat) Sdn , RNZAF (a/c NZ4020) commanded by FGOFF George Hitchcock based at USS Coos Bay. Rescue mission protection was flown by P-40s [See Dumbo Diary by Jenny Scott for particulars]

Larry Seth Steinberg (son of SSgt Lester A Steinberg 11033824)

My Father Leonard W. Harris served in the RNZAF in Bouganville, Solomon Isands between 1944-45. He was an LAC. (Leading Aircraftsman-probably equal to a Corporal and he drove the “Follow Me ” jeep for the Corsairs we were equipped with. A fairly dangerous job with a 2000 hp. engine and propeller a few feet behind him. He also scrounged stuff from the U S dumps as we were not fully supplied with first rate goods.

My Uncle was the A.N. Saward (14 RNZAF) referred to in the articles above killed trying to save a fellow airman in the Pacific in dying days of the war.

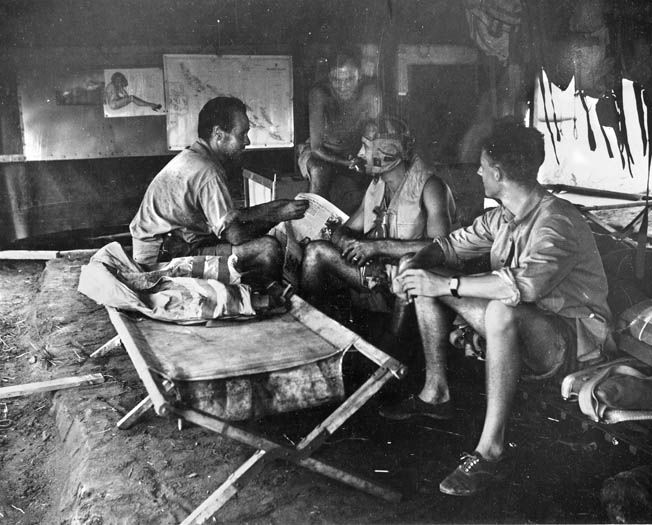

Couple of things … the photo of pilots being briefed next to a “P-40” should possibly be substituted. This is definitely a Hawker Hurricane (never used by the RNZAF) with what look to be RAF roundels. Also the banner at the top of the article shows Royal Australian Air Force Bristol Beauforts … which were used in the Pacific theatre but never by the RNZAF.

My Grandfather (Flt Lt Alistair Stevenson DFC) was a pilot flying Hudson’s with the first echelon (3BR sqn) of the RNZAF from Henderson in 1942/43 and flew 78 missions on his second tour in the theatre flying PV-1 Ventura’s from Emirau and Green island.