By Matt Broggie

“There’s no greater feeling in the world than seeing Old Glory in a winning position.” Twenty-one-year-old U.S. Navy Ensign Joseph Bale watched the American flag raising on Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi from aboard the attack transport USS Dickens County Texas.

As boat group leader of the third wave of U.S. Marines assaulting Iwo’s Green Beach, Bale’s role in the invasion was completed within its initial hour. Bale, along with every American sailor and Marine who saw the flag flapping in the wind, assumed the battle would soon be over. The invasion of Iwo Jima had been under way for four days, and the troops felt victory was already overdue. Bale would be surprised to learn the battle would last for 32 more arduous days.

“And That, My Dear Friends, is How I Got to be a Naval Officer”

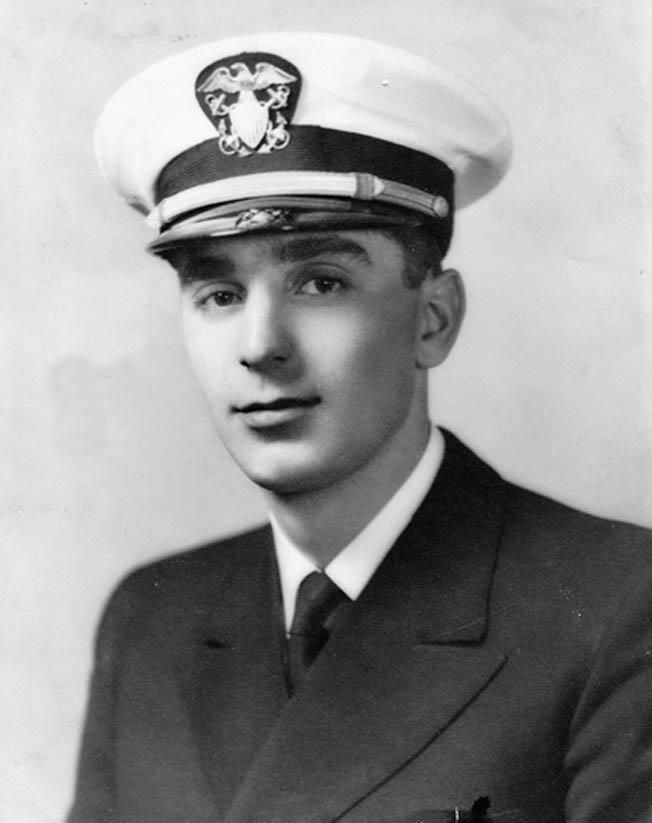

Born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, Joseph Bale enlisted in the Navy at the age of 18. He became part of the V12 program at Central Michigan College and was chosen as one of 10 students for midshipman’s school at Colombia University in New York. The school instilled strict military discipline through marching, drilling, calisthenics, seamanship training, ordnance, and bookwork. “It was the toughest thing I’ve ever been through,” Bale recalls. Fortunately, he was intelligent and athletic and graduated as one of 600 out of an original 1,600 students. He was commissioned a naval ensign.

One of his most memorable moments of midshipman’s school was his exit physical. Bale had poor vision in his right eye but managed to pass all prior eye exams by literally memorizing each chart according to a large number printed on it.

Just prior to the eye exam a doctor listened to his heart and said, “You’re going a mile a minute! What’s going on?” Bale told him, “I’m a little afraid of that eye exam.”

The doctor said, “Well I can’t clear you now, come back after the eye exam.”

“I then proceeded to the eye exam line, forlorn and down-hearted,” Bale remembers. As he was nearing the testing area, Bale whispered to the sailor in front of him, “What’s the number on that eye chart?”

The sailor turned around and said, “Where do you see the eye chart?”

Bale laughed, “He couldn’t even see the eye chart!”

As the moment arrived, Bale strained to make out the letters or even the chart number but was unable to do either. So recalling the list of eye charts he had memorized, he picked one and blurted out, “A,E,L,T,Y,P,H,E,A,L,T.” Today Bale still recites it in rapid succession.

The doctor grinned and told him, “Okay, go ahead.”

As Bale walked passed the eye chart, he looked at the line and realized he was completely wrong. The doctor passed him despite failing the exam. Years later, he proudly proclaimed, “And that, my dear friends, is how I got to be a naval officer.”

A Secret Visit by the President

After graduation, Bale was sent to the amphibious training base in Coronado, California. For the 19-year-old kid from Detroit the oceanside environment was a pleasant change. “It is a gorgeous piece of land,” he said.

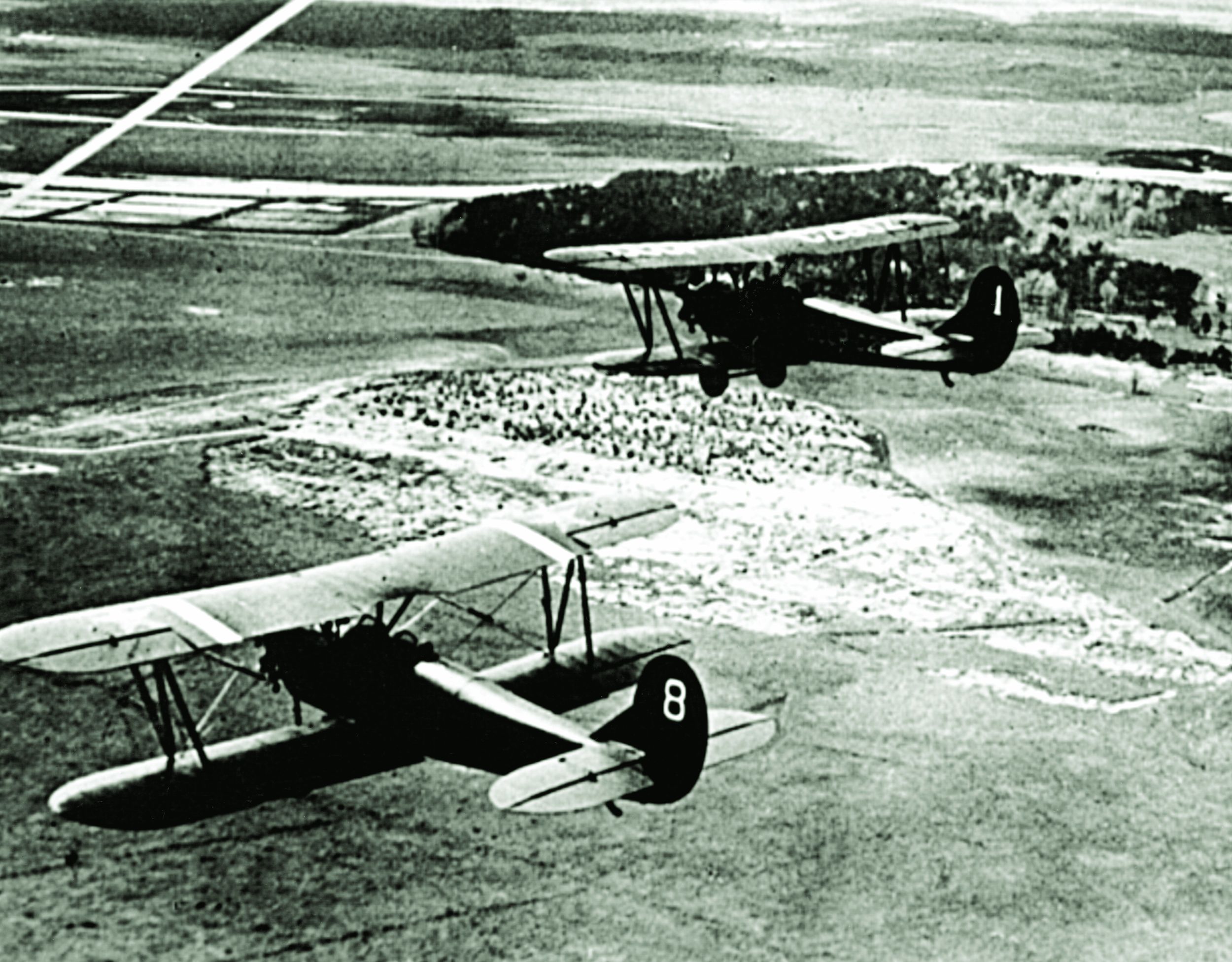

Bale began to train for beach invasions. “The boats we trained in were landing boats. We would land on the beach and then retract back into the water,” he said. The sailors trained with multiple types of landing craft and received training on the gyroscope compass, which is favored in ocean navigation because of its ability to find true north as opposed to magnetic north.

One day while Bale was guarding the base’s front gate, he was overwhelmed by the arrival of two visitors in a black limousine. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt had come to witness the amphibious training and visit their son, James, a founder of the Navy’s frogman program.

The visit from the president and first lady was kept a complete secret. “They didn’t even let the junior officer on the gate know the president of the United States was coming in! I’m just a kid going berserk not knowing what the heck to do,” remembered Bale.

From Coronado, Bale went to the Navy port in Portland, Oregon, and was officially assigned to the USS Dickens County Texas. The Dickens was a 455-foot troop carrier ship called an APA (Auxiliary Personnel Assault). APA ships could carry approximately 26 landing craft or other small boats. Across the dock from the Dickens was the escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea.

Bale still vividly remembers the fate of the Bismarck Sea, sunk by Japanese kamikaze aircraft during the battle for Iwo Jima. While in Oregon, Bale and the rest of the crew participated in sea trials. Bale recalled, “I’m now in charge of the gyroscope compass compensation during the sea trials for my ship.”

Heading to War on the Dickens

He was also responsible for training other sailors to use the compass on other ships in his division. The Dickens passed the trials, and on October 18, 1944, the ship departed for San Francisco to pick up additional landing craft. While en route large swells caused the Dickens to pitch and roll with such force that two landing craft were thrown overboard.

Once in San Francisco, Bale was given an errand: “I had to go ashore at the Captain’s request to pick up two [replacement] boats that were waiting for us. I presented them with a requisition from the Navy for $450,000. That’s two boats!” After San Francisco, the Dickens departed for Leper Island, Hawaii, where the sailors rehearsed landings and practiced firing their cannons. From Hawaii, the Dickens went to war.

Filled with 1,300 men of the 5th Marine Division, the Dickens set sail across the Pacific. Sometime after leaving Hawaii, while Bale and the rest of the crew were trying to figure out exactly where they were headed, an unexpected source revealed the destination. “Tokyo Rose announced, ‘The 5th Marines are now headed for Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands,’” Bale recalled. “How does she know when we don’t even know? [We] had been trying to figure out where we were going and then she tells us. Then we would look on the charts and Iwo Jima was just a dot.”

Despite her demoralizing propaganda, Bale enjoyed listening to Tokyo Rose. “We liked her because she played all the great American music. She was on our radio every day and night. That got us young guys who were great dancers [excited].”

Planning the Attack on Iwo Jima

The sailors began studying the three-dimensional sand tables of Iwo Jima. Stretching eight square miles. One of the Volcano Islands, it is located 660 miles south of Japan in the Philippine Sea. Shaped like a pork chop, the island reeks of sulfur and is dominated by 550-foot Mount Suribachi on its southwest tip. With its volcanic nature and lack of greenery, the island resembles the surface of the moon. To the north are the highlands of the Motoyama Plateau at 300 feet.

Iwo Jima had two completed airfields and a third under construction. American intelligence reported there were 13,000 Japanese defending the island, when in fact there were 21,000.

For 72 days beginning on December 8, 1944, American bombers hammered the island, followed by a three-day naval bombardment concluding on D-day. The thorough bombardment was a great comfort to Bale. He also rested in the evidence of the reconnaissance photos taken by Navy frogmen that showed “not a weed living on that island, not a living insect from all the months of bombing.” Despite the extensive bombing, the Japanese suffered few casualties.

At 7 am on February 19, 1945, Bale and his crew of four men had their LCVP in the water off the shore of Iwo Jima and were heading for the rendezvous point. An LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel) is a 36-foot flat-bottomed boat that can transport 36 combat-loaded troops or two small vehicles. Once an LCVP ran ashore, a ramp would drop from the bow and allow for easy unloading of its cargo. Another landing craft, the 36-foot LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked), is fitted with tank tracks for ground transportation once it reaches the shore. At the rendezvous point Bale met up with the 12 LVTs he was to lead to the beach. Each LVT carried a platoon of 36 anxious Marines.

Bale continued with the initial steps of the carefully orchestrated invasion plan for D-day. “The timing was the main element, otherwise it would be catastrophe,” he recalled. The Iwo Jima landing was the pinnacle of an evolution of beach landings for the U.S. Navy. “We were going to show the world how beautifully we can do it and also make the American public aware that we don’t always make mistakes since we had gone through a great tragedy at Tarawa.”

The landings were to be so perfectly executed, a VIP crowd aboard the amphibious command ship USS Eldorado came to witness it. Aboard the Eldorado was General Holland M. Smith, commander of the Marine V Amphibious Corps, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, and their staffs.

The Marines would be attacking at two points on the island. The primary site encompassed two miles of black sandy beach on the south shore stretching westward from the foothills of Suribachi. The second landing site was to the north of Suribachi on the western shoreline. The first beach was divided into sectors from west to east: Green Beach, Red 1 and 2, Yellow 1 and 2, and Blue 1 and 2.

“Too Late to Worry”

Bale’s boat group was in the third wave that assaulted Green Beach, closest to Suribachi. As Bale arrived at the rendezvous point, the U.S. Navy pounded the island. Bale took notice of a crater the battleship USS Tennessee made on the slope of Suribachi with its huge 14-inch guns. He headed in to the line of departure, eight miles from shore. Now just after 8 am, the naval gunfire ceased and 120 carrier-based planes headed for the island.

“Now we’re getting heated up,” Bale remembered.

Some planes strafed the beach with rockets and gunfire. Others dropped bombs and napalm over the face of Suribachi. The Marines cheered and yelled, thinking that no one could survive such an onslaught. Thirty minutes later the planes dispersed, and the Navy guns recommenced.

The first wave of armored LVTs with mounted 75mm cannons moved toward the beach. Soon after, the second wave followed, and then it was Bale’s turn. He led the way to Green Beach. Bale was faced with the words “Too late to worry,” which his coxswain had painted on the ramp of his boat. “Going in I kept all 12 of my boats abreast,” he said.

As Bale’s LCVP moved toward the beach, Japanese artillery opened up. When the Japanese shells came in, he remembered, “the Eldorado with its VIPs started backing up real fast, getting the hell out of there.”

As the third wave approached the beach, Bale noticed that the crater on Suribachi from the battleship Tennessee’s guns had expanded. “The Tennessee had been out there for hours just poom, poom, poom, and it looked like the small crater had now split the mountain.”

“All Hell Breaks Loose”

Bale felt the LCVP slide against the sand. His coxswain immediately threw the boat in reverse to prevent it from broaching in the waves. As the tracks of the 12 LVTs churned in the soft sand, they lurched forward from the water and progressed up the beach. “I let them go, I turn around to come back,” and then at about 40 feet from the shore Bale recalled, “all hell breaks loose.”

An LVT full of Marines coming in to Red 1 Beach was hit by a Japanese shell and exploded. The Marines were flung all over the water, and the LVT instantly sank. Despite the danger of the Japanese shells splashing the water all around him, Bale ordered the coxswain to steer over to the Marines now floating in the water. When they got close enough, Bale and his crew frantically pulled men out of the water.

“It’s not easy picking up a guy that’s soaking wet with a pack,” Bale said. The scene was too much for some of Bale’s crewmembers. “I remember my coxswain, who was such a tough guy aboard ship, started crying.”

After they pulled the last Marine they could reach out of the water they headed for a hospital ship. “We got 18 of them out, couldn’t get more which is terrible. That’s been kept in my memory for a long time.”

On the way to the hospital ship Bale gave a shot of morphine to a sergeant with a hole blown through his huge bicep. The sergeant asked for a cigarette, and Bale gave him one. The rest of the Marines had no major injuries, but Bale remembers them being “shell shocked.”

Bale’s LCVP eventually arrived at the hospital ship. “It was so early in the invasion I had to wait for the [hospital ship] to take its position before I could give them patients. I waited around for about 20 minutes,” he added. After unloading the wounded, Bale returned to the Dickens, and his main duty for D-day was over.

Kamikazes Against the Bismarck Sea

During the next few days Bale carried out assignments aboard the Dickens. At night, the APAs pulled several miles back from the island. The Japanese had been seen swimming out to the U.S. ships with explosives attached to their bodies.

“We caught a couple of these swimmers near Suribachi,” recalled Bale. “One of our boats saw one and got rid of him with a machine gun.”

In the morning, the ships would return to their positions near the island. On D+2, February 21, just after sunset, Bale was in his LCVP with hundreds of other landing craft moving in a giant circle. The beaches had become too congested with crippled tanks, landing craft, and supplies for additional boats to come ashore. This circular maneuver was performed to maintain order among the boat groups while they waited to go ashore.

As the daylight faded, Bale heard the sound of plane engines. In the darkness, he made out the shapes of Japanese aircraft. “They flew right over us,” he recalled. Soon Bale saw massive explosions from American ships. His LCVP and the other boats in the circle headed to the site. As they neared the area, word spread that two kamikazes had crashed into the Bismarck Sea. Bale’s crew thought of the Bismarck Sea as their “sister ship” since they both had come from Portland and had set out to sea the same day.

“We knew a lot of the guys from the Bismarck Sea from going to bars and other things in Oregon,” he said.

Now with the fire from the sinking aircraft carrier as the only source of light, Bale began picking men out of the water. The rescue effort lasted 12 hours. In the end, 605 sailors were plucked from the sea, and 318 were either killed by the explosions or drowned. In the same attack, the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga was heavily damaged but managed to stay afloat. The Dickens was quickly converted into a hospital ship, and the wounded were brought on board. A survivor was even placed in Bale’s cabin.

Witnessing the Flag Raising on Iwo Jima

The battle for Iwo Jima raged on. Marine casualties increased as they made slow progress against the Japanese. On February 23, two American flags went up on Suribachi after Marines climbed to the top. The first flag was raised as Bale was on the bridge of the Dickens. Amid loud cheering from Marines all over the island and ships blowing their horns and whistles, Bale swelled with pride as he watched the Stars and Stripes flap in the wind on top of the mountain.

A couple of hours later a larger flag was brought up, and Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal snapped the shot that would immortalize the moment forever. Two days later, the USS Dickens, loaded with 455 survivors from the Bismarck Sea and about 500 more wounded men, headed for Saipan.

En route many of the wounded succumbed to their wounds. “We were burying them at sea every night,” Bale recalled. Soon after arriving in Saipan, he received bad news. In a letter from home he learned that his cousin in the Army, also named Joseph Bale, had been killed while fighting in southern France.

Before the war the two Joes had been inseparable. The news was devastating to Bale. “I cried for three days.” Bale’s cabin mates took his turn on watch and brought him food. “I was just out of it.” Cousin Joe was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions. Bale received this news as the crew of the Dickens prepared for yet another invasion. Eight hundred fifty miles west of Iwo Jima sat the island of Okinawa. The Dickens would be part of the landings there.

On Okinawa and Hiroshima

Recently promoted to lieutenant (j.g.), Bale was made beach master for the landings at Okinawa. “Thanks a lot for the honor,” he sarcastically commented. Beach masters in the Pacific Theater had a life expectancy of about 10 minutes. However, the landings at Okinawa were a sharp contrast to those at Iwo Jima.

“I could have had a hammock there and taken a six-hour nap,” he remembered. Bale was beach master of Purple Beach, and the Japanese did not contest the landings there. Brutal fighting later went on for 82 days from April 1 to June 21, 1945. American forces took the island in the end, but a huge price was paid with 50,000 Americans wounded and 12,000 killed. Over 100,000 Japanese soldiers were killed defending the island.

After Japan surrendered, Bale had the unique responsibility of escorting eight scientists ashore near Hiroshima a month after the dropping of the first atomic bomb. While the scientists walked around with Geiger counters, Bale acted as “a secretary to document and legitimize anything they found.”

While walking through the streets Bale came across an old truck. “I went up to it and we were told not to touch anything, so I didn’t want to hit it with my arm,” he said. “So I pushed it with my foot and the whole thing collapsed into sand. It was pulverized. You wouldn’t know two minutes before what was a headlight or a motor or a door.”

Returning Home

With the war over, the Dickens began transporting troops home to the United States. Bale, too, eventually made it home to Detroit in December 1946. Bale’s father was a sales representative for furniture factories across Michigan and northern Ohio, and he joined the family business. For 29 years he worked as a salesman for furniture factories.

Bale moved to the West Coast in 1981 and led a happy life in the oceanside community of Ventura, California. He became the proud father of four children and grandfather of six.

Joseph Bale passed away July 18, 2012, just shy of his 89th birthday. His obituary spoke of his life in the Navy and the joy he received while spending time with his grandchildren. When asked what he would like people to know about his father, Joe’s son, Ron, responded, “He was always an advocate for those less fortunate and the oppressed minority. This is what he taught me through word, and more importantly, example.”

Thank you for this story. It is important these men and their memories be preserved.