By Chuck Lyons

The Hussites, all but forgotten today, were a 15th-century sect of religious reformers, forerunners of the Protestant Reformation that was to come a century later. Remnants of their ideas still exist in several Christian groups, including the 825,000-member Moravian Church, or Unity of Brethren. But when history remembers the Hussites at all, it is more for their “hand cannons” than for their religious zeal. Using these handheld gunpowder weapons, the Hussites fought and defeated formidable armies sent by the Holy Roman Empire, the Catholic Church, and the Kingdom of Bohemia. Theirs was the first use of such weapons in Europe, and it changed forever the face of European warfare by demonstrating that properly armed infantry could defeat armored knights on horseback.

The Spread of Gunpowder

It is generally accepted that gunpowder had existed in China since at least the 8th century, although some modern researchers have speculated that it was developed in several places simultaneously. The knowledge of its composition and use spread from the Far East westward into the Moslem Middle East. One Arab commentator claimed it was used in primitive cannons against invading Mongols in ad 1260, cannons that were probably bamboo tubes reinforced with iron and used to fire an arrow. (Other Arab commentators dispute this claim, believing that it was the Mongols who first introduced gunpowder to India).

From the Middle East, gunpowder spread along the Silk Road into Europe, or was introduced by invading Mongols. Whatever route it traveled, it is established that gunpowder had arrived in Europe by the 13th century, when Roger Bacon, the English alchemist and philosopher, described its ingredients. “We can, with saltpeter and other substances, compose artificially a fire that can be launched over long distances,” Bacon wrote in his Opus Maior in 1248. “By only using a very small quantity of this material much light can be created accompanied by a horrible fracas. It is possible with it to destroy a town or an army.”

In 1250, a Norwegian manuscript also mentioned gunpowder’s composition of coal and sulphur as an excellent weapon for sea battles. The first true cannon came along 100 years later and is usually credited to the German friar Berthold Schwartz, who has also been credited with independently inventing or discovering gunpowder. Crude siege artillery was used as early as 1326, and by the mid-15th century gunpowder weapons had been developed into massive cannons capable of hurling 750-pound stones.

Cannons in the West

The first use of cannon for military purposes in the western world was probably the Moorish cannon used in the defense of Seville in 1248 and of Niebla in 1262. In both cases, the city’s Arab residents fired some sort of primitive gun at the Spanish who were besieging them. The first metal cannon was probably the pot-de-fer that was presented to Edward III upon his accession to the English throne in 1327. It was essentially an iron bottle (the name is French for “iron pot”) with a narrow neck that was loaded with gunpowder and fired an iron bolt feathered with iron.

Such cannons may have been used in the 1337 siege of Stirling Castle during the Second War of Scottish Independence. There are sporadic mentions of gunpowder weapons throughout the 14th century, and in 1338 a French raiding party sacked and burned Southampton, England, using, besides the normal arms of the time, a ribaudequin, which is basically a large bow with 48 bolts, and three pounds of gunpowder. In 1346, cannons were used at the Battle of Crecy, and in 1350 Petrarch, the Italian poet and scholar, wrote that cannons on the battlefield were “as common and familiar as other kinds of arms.”

The Early Handgun in Europe

Europeans contributed to the development of gunpowder technology by introducing “corning,” a process that added liquid to the gunpowder mix and allowed the formation of larger and more regularly sized granules, which in turn settled the dust and contributed to gunpowder’s reliability and consistency. Other developments in the making of gunpowder, especially the advent of saltpeter farming, resulted in the price of powder falling as much as 50 percent at the beginning of the 15th century, a development that allowed the manufacture and use of more and more gunpowder weapons. By 1411, John the Good Duke of Burgundy had some 4,000 handguns stored in his armory.

References to “guns with handles,” hand-held weapons, had existed for some time in the Orient, but they were first made by European sources about 1350. Such guns may have been available before that time, however. Early hand- held weapons were called culverins, a term derived from the Latin, colubrinus, or “of the nature of a snake.” They were useful but not popular.

These weapons and the men who used them were looked down upon in a society still dominated by chivalry and controlled by armored and mounted knights trained for hand-to-hand combat. That condescending attitude continued into the 16th century, when church authorities railed against the use of gunpowder weapons, calling them blasphemous and linking them to the so-called black arts of witchcraft and devil worship. But by the mid-14th century, even the Pope’s forces were using gunpowder weapons. The handheld guns of the day were limited in their use, however, due to their cumbersomeness and difficulty of loading, which could not be accomplished on horseback.

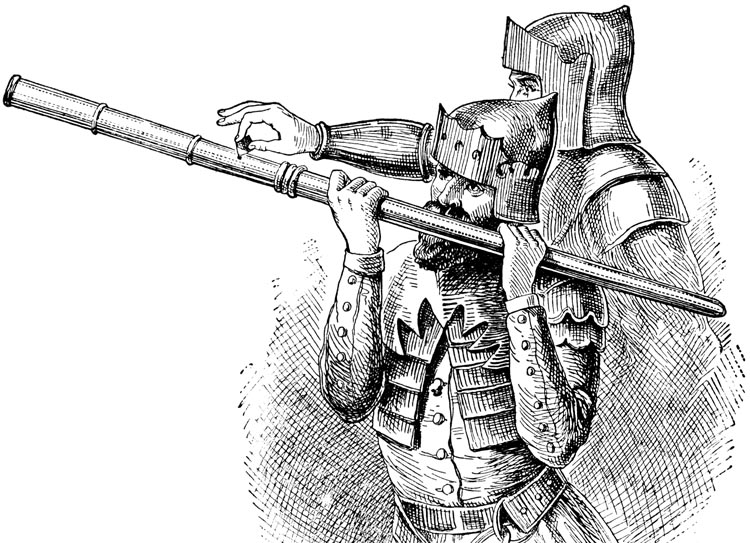

Early Hand Cannon Design

Early handguns were simply smaller versions of cannons. They were single-shot, smooth-bore, muzzle-loading tubes eight to 12 inches long and closed at the breech end with the exception of a small touch hole. A slow match was applied to the touch hole to fire the weapon. The slow match, which was itself another European innovation, was a piece of cloth that had been soaked in potassium nitrate and then dried, which enabled it to smolder without going out. Hand cannons generally were made of bronze or brass, although a few were made of iron. They rested on a rounded piece of wood that was held under the arm of the gunner or leaned against the ground to steady the gun. These handles also protected the gunner from the heat of the discharge and helped control the weapon’s recoil.

A German document from 1390 indicates that the barrels of such weapons were filled with powder for about three-fifths of their length, followed by a wooden sabot and then an iron or stone ball. Others were less sophisticated, firing arrows or even pebbles picked up from the ground. Handling the weapons required the gunner to use one hand to hold the gun and the other to apply the slow match. In some cases, however, the gunner held his hand cannon in both hands while the slow match was applied to the touch hole by an assistant. Around 1425 a method was developed for attaching the slow match to the gun with an S-shaped mechanism that lowered the match by means of a lever. This allowed the gunner to fix his full attention on where he was aiming rather than on the match being brought to the touch hole.

Early hand cannons had the ability to pierce some armor, were inexpensive, and could be mass produced. The flash and noise given off by the igniting gunpowder—Bacon’s “horrible fracas”—had a psychological effect on an enemy. Their penetrating power and speed of operation were roughly equivalent to that of the then popular crossbow, but unlike the English longbowmen, gunners could be quickly and easily trained. The guns had a further advantage in that the forging methods required in their manufacture meant that centralized governments had a measure of control over their production and the manufacture of ammunition—an important consideration in a time when violent rebellion was commonplace.

The Hussite Wars: Modernizing the Use of Gunpowder

It was not until the Hussite Wars of the early 15th century, however, that modern tactics were developed to enable gunpowder weapons to make a decisive contribution to European warfare. The Hussite Wars were a series of engagements in Bohemia begun in 1419 by the followers of Jan Hus, a Czech priest, philosopher, and reformer who had been accused of holding “heritical views,” condemned by the Roman Catholic Church, and burned at the stake on July 6, 1415.

Originally an internal church conflict launched when followers of Hus rose up after his death demanding church reform (a movement that prefigured the Protestant Reformation a century later), the Hussite Wars turned into a wider Czech rebellion that spilled into significant areas of Silesia, Hungary, Lusatia, Meissen, and Saxony. The Pope himself eventually called several crusades against the rebels, and in 1430 Joan of Arc entered the conflict, sending a letter to the Hussites threatening to lead a crusading army against them if they did not return to “the Catholic Faith and the true Light. If I wasn’t occupied in the English wars,” she warned, “I would have come to see you a long time ago; but if I don’t find out that you have reformed yourselves I might leave off [fighting] the English and go against you, so that by the sword, if I can’t do it any other way, I will eliminate your mad and obscene superstition and remove your heresy or your life.” Joan’s capture by English and Burgundian troops two months later kept her from carrying out her threats.

The Hussite “War-Cart Strategy”

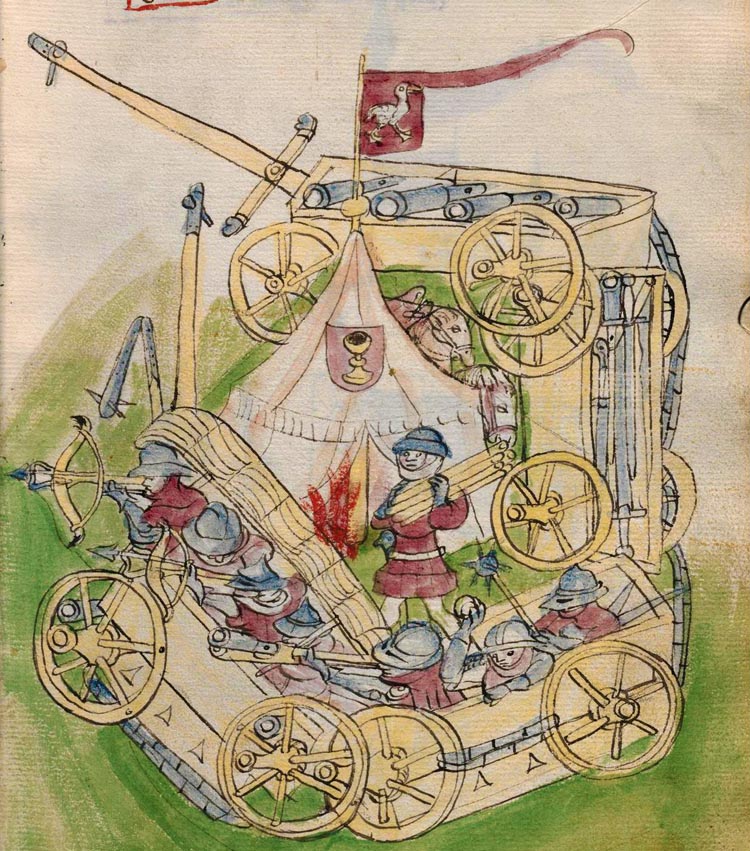

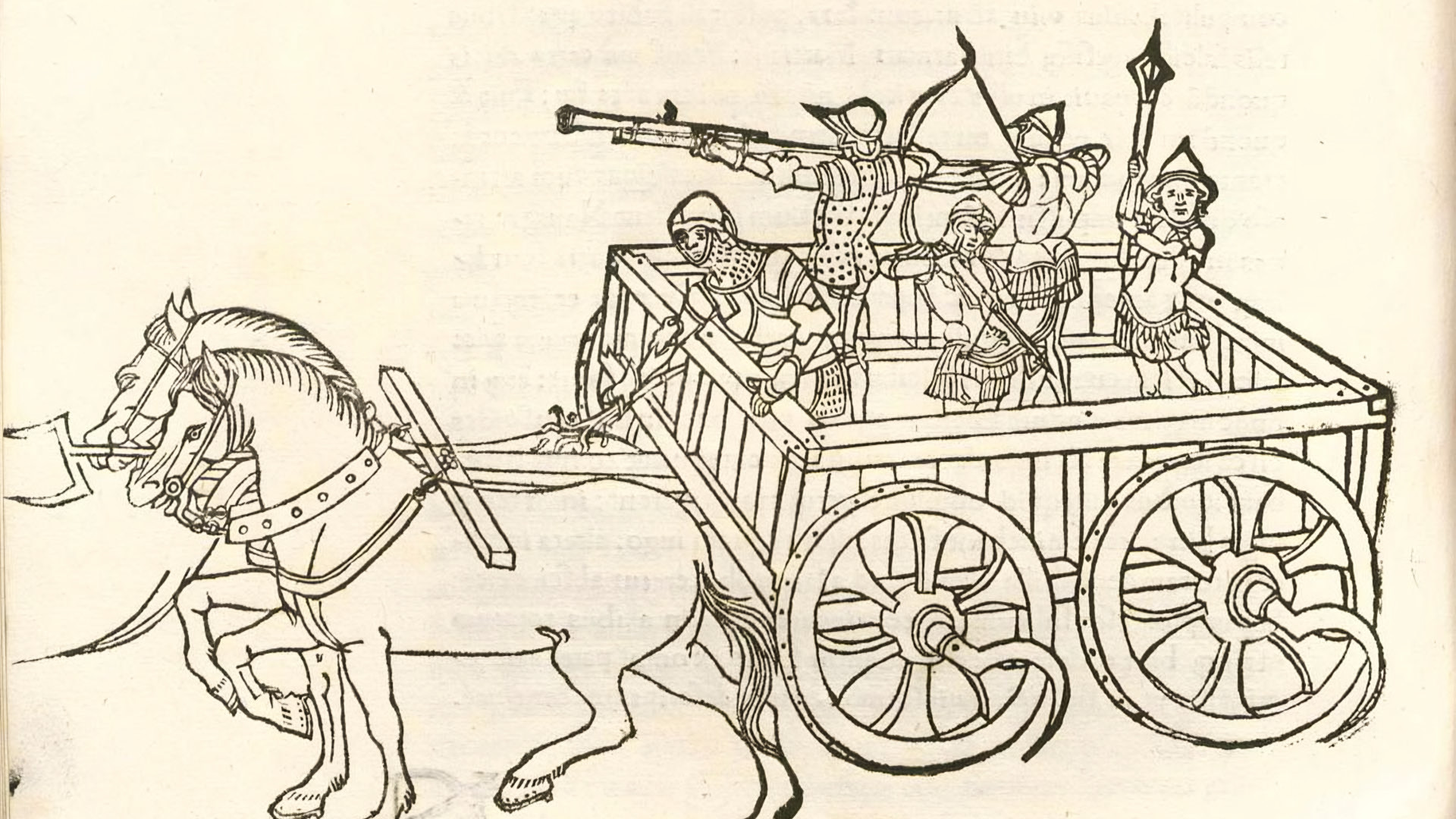

Originally, the Hussites fought a defensive war, but by 1427 they had begun to take the offensive. It was during this latter period that they developed what became known as their “war-cart strategy,” named for the cart column in which Hussite forces traveled and fought. The wagons in question were simple rectangular farm wagons with stout planking rising three to four feet high from the wagon bed. At the top of the sides, some of which were armor plated, additional planks were hinged. These could be raised and fixed in place, forming a wall through which hand-gunners and crossbowmen could fire from cover. Below the body of the wagon was another hinged plank, pierced with firing slits that could be lowered to close off the space beneath the wagon and create additional cover for hand-gunners and crossbowmen.

Bags of rocks were attached to the wagons to provide stability and, in case of emergency, be hurled at the enemy. The Hussite strategy consisted of forming the horse-drawn war carts, or tabors, into squares or circles, joining them wheel to wheel by chains, with their corners attached to each other and a ditch in front. Shields or thorny brushes were stacked in the openings between the carts. The crew of each cart consisted of 30 to 44 men, including four to eight crossbowmen and two hand-gunners, two drivers, foot soldiers, pikemen, and shield carriers. Hussite cavalry was massed inside the circled wagons. The ensuing gunfire created havoc among the enemy’s armored knights.

The Hussite wagon squares had the added advantage of supporting one another in the close fighting that would follow an attack. The artillery consisted primarily of four types: a tarasniuc, a four- or five-foot-long gun with a two-inch bore; a haufnitze (from which the modern word “howitzer” may have originated), a short-bodied gun with an eight- to 12-inch bore; a bombard, a large-caliber cannon or mortar that fired large stones; and small cannon. The guns were mounted on specially built war wagons that allowed for their recoil. Some of the weapons were siege guns, and it is probable that the haufnitzes and tarasniucs were used to hurl canister at the enemy.

Battering the enemy’s close-formed knights with such artillery would finally provoke a charge by the proud knights. Such a charge was met by the Hussite gunners and crossbowmen. Any enemy horsemen who survived the initial fire and were able to get between two wagon circles would find themselves caught in a deadly crossfire.

A major Hussite aim in the fighting was to disable the knights’ horses so that they dismounted, making the cumbersome knights easier targets.With the enemy weakened, Hussite infantry armed with flails, swords, and pikes as well as the Hussite cavalry would attack from behind the carts, usually striking the dismounted and disoriented knights from the flanks. The knights, caught between the flanking attacks and the fire from the carts and unable to escape because they had been dismounted, would be annihilated. Over time, the Hussites developed a reputation for not taking prisoners, a bit of psychological warfare that further demoralized the enemy.

The Effect of Wagon Tactics on Gunpowder Warfare

The wagon tactics, which were developed by the Hussite’s half-blind military leader Jan Ziska, have been called “one of the most imaginative and offensive minded use of field fortifications.” The Hussite wagon fort was not, however, a new idea. The term “wagon-fort” had been mentioned as early as the the 4th century by a Roman army officer, and the Chinese used such formations at the Battle of Mobei in 119 bc.

The Hussite wagon forts have been likened to the battle squares used by Wellington at Waterloo. What the Hussites had done was to combine the wagon-fort idea with the existing crossbow and the newfangled hand cannon. The result was devastating. Such weapons and tactics allowed Hussite forces to win major battles against armed knights throughout the 1420s and 1430s. It was not until 1436 that the Hussites, troubled by internal dissension, were brought to the peace table.

By then they had achieved nothing less than a revolution in tactics, one that prefigured the end of the age of chivalry and initiated the resurgence of infantry as the weapon of choice on the battlefield. Their introduction of gunpowder also presaged a social revolution. Now even an illiterate peasant could overcome a noble knight. It was a lesson that, once learned, was never forgotten.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments