By Nathan N. Prefer

On January 17, 1945, as Allied forces prepared to descend on Germany itself and put an end to the war in Europe, an American tank battalion disappeared. The 43rd Tank Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Scott Hall, organic to the 12th Armored (“Hellcats”) Division’s Combat Command A, joined with the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion to push German forces out of the town of Herrlisheim in France’s Alsace region. Shortly after the battalion entered the town, some garbled but seemingly desperate messages were received by Combat Command A from Colonel Hall. Neither Hall nor his battalion was ever heard from again.

It was not until 1940 that the United States War Department made the first move to create tank, later armored, battalions within the U.S. armed forces. Originally only 15 were authorized, half “heavy” and half “light.” The original battalions consisted of a Headquarters and Headquarters (H & H) company and three tank companies. Each tank company consisted of three platoons of five tanks each, with a headquarters section of two additional tanks. In 1942, a service company was added. Later additions included a light tank company, an assault gun platoon, a mortar platoon, and a reconnaissance platoon. By 1943, the battalions usually had a total of 54 medium tanks, 17 light tanks, three assault guns (105mm howitzers), three 81mm mortar halftracks, and numerous support vehicles. A fully staffed tank battalion numbered 729 officers and enlisted men.

By January 1945, the standard American armored division numbered 10,937 officers and men, 195 medium tanks, 18 105mm self-propelled howitzers, and several other armored vehicles within the supporting reconnaissance, engineer, medical, and service units. But the bulk of the division’s fighting power rested in the three tank battalions and three armored infantry battalions, which were usually paired under one of three (A, B, and R or Reserve) combat commands. In all, the U.S. Army fielded 16 armored divisions during the war, all of which served in the European or Mediterranean Theaters.

One of these was the 12th Armored Division, which was activated at Camp Campbell, Kentucky, on September 15, 1943. After a year’s training it moved to Tennessee to participate in Army-wide maneuvers and then to Camp Bowie, Texas, for additional training. The division’s combat elements consisted of three tank battalions, the 23rd, 43rd, and 714th; the 17th, 56th, and 66th Armored Infantry Battalions with the 119th Armored Engineer Battalion and 92nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. By September 1944, the division was at Camp Shanks, New York, preparing to go overseas. The division’s troops, who called themselves the “Hellcats,” arrived at Le Havre, France, on November 9, 1944, after a month’s stay in England. Originally assigned to the Ninth U.S. Army on the northern end of the American front lines, they had barely sent forward advance parties to scout out their area of operations when orders changed.

Joining the Seventh U.S. Army

The 12th Armored Division, now commanded by Maj. Gen. Roderick R. Allen, unexpectedly found itself assigned to the Seventh U.S. Army, Sixth Army Group, one of three Army Groups under the control of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) commanded by General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The Sixth Army Group was at the extreme southern end of the Allied front lines in France.

General Allen was a rarity among divisional commanders in the U.S. Army during World War II. He did not attend West Point. Instead, the Texas-born commander received a Bachelor of Science degree from the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Texas in 1915 and was commissioned into the cavalry the following year. He served in France during World War I and later graduated from the Command and General Staff School and the Army War College. He had served in various posts with armored units since 1940 and had been promoted to major general in February 1944. He commanded the 20th Armored Division in training before assuming command of the Hellcats in September 1944.

The Sixth Army Group was also unique at this point. While half its units were experienced U.S. Army units, some of which had first seen combat in North Africa in 1942, the other half were French, the newly introduced French First Army. Commanded by Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, it had landed in southern France on August 15, 1944, and had been fighting its way to the Rhine River and Germany ever since.

The 12th Armored Division joined the American half of Sixth Army Group, the Seventh U.S. Army. Under the command of Lt. Gen. Alexander (“Sandy”) M. Patch, the Seventh Army was pushing north and east to reach the Rhine River, the traditional boundary between France and Germany. Moving up, the leading units of Combat Command A entered the combat zone at Weisslingen on December 5, 1944, and soon relieved elements of the veteran 4th Armored Division. Here the first shots were fired by Battery A, 493rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. The division’s first success came with seizing the town of Singling and piercing the Maginot Line in its sector. After crossing the German border on December 21, 1944, the division was pulled out of line for a brief rest and recuperation period.

In this most difficult season, the weather in sunny southern France was anything but. The area in which Seventh Army operated in December and January 1944 was a wet, cold quagmire of mud, rain, and snow. Soon the Americans were whitewashing their tanks to blend with the snow-covered landscape. Nor could the local population be relied upon. Alsace Province had been under German control for years, and some inhabitants were German sympathizers. In one instance, the soldiers of Battery A, 495th Armored Field Artillery Battalion were puzzled by the accuracy of German counterbattery fire against them despite their best efforts at camouflage. They soon discovered that a dog, which made the same journey past their positions each day, was actually carrying the coordinates of their guns to the enemy then returning home to its master within the American lines.

The 43rd Tank Battalion’s First Action

The initial action of the 43rd Tank Battalion occurred on December 12 when, paired with the 66th Armored Infantry Battalion, it successfully attacked the towns of Guising and Bettviller in daylight. Casualties were light, and the battle went according to plan. Shortly after this first victory the division was relieved by the 44th Infantry Division and went into reserve. While in reserve the division’s officers discussed what had worked in their first action, what had failed, and what they needed to do to improve their combat performance.

Combat Command A, led by Brig. Gen. Riley Finley Ennis, another non-West Point officer, moved back to the front on December 18 and once again relieved elements of the 4th Armored and 80th Infantry Divisions. These units were being pulled out to move north to attack the flank of the massive German offensive through the Ardennes that had hit the First U.S. Army hard. Part of General George S. Patton’s Third Army, which held the front line just north of Seventh Army, they were badly needed to halt the Germans. Because of this, General Patch’s Seventh Army would be required to cover more of the front lines as Patton pulled his troops to the north. As a result, the Hellcats’ rest period was cut short.

Anticipating a New German Offensive

The day after Combat Command A returned to the front a major conference was held at the French town of Verdun. Present were Generals Eisenhower, Omar Bradley (commanding 12th Army Group), and Patton. Concerned about the massive German attack in the Ardennes, what would come to be known as the Battle of the Bulge, the decision was made to pull Patton’s Third Army to the north and to halt all offensive operations of the Sixth Army Group. Devers was even instructed to give up ground if necessary to maintain a continuous front line with 12th Army Group. Devers was disappointed at his new orders, but they were obeyed. While awaiting the outcome of the battle to his north, he made plans for a renewal of his offensive in the first week of January 1945, when he believed the northern emergency would be over.

In late December 1944, Patch’s Seventh Army had six infantry and two armored divisions available. While the Hellcats were holding a sector of the front, Patch kept the 14th Armored Division in reserve. The frontline units had to hold a line that was 126 miles long, which meant that each battalion was responsible for a front of some two miles, far beyond the usual demands on a battalion. Because of priority given to the northern group of armies, supplies and equipment in Sixth Army Group were dwindling, as were sufficient replacements for casualties. Worse, intelligence officers began reporting signs of a German counteroffensive aimed at Seventh Army; whether it was a diversion or a real offensive remained unclear.

The 12th Armored Division was now a part of the XV Corps under Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip. It was backing the frontline defenses of the 44th, 100th, and 103rd Infantry Divisions. Operations were limited to sending out patrols, repulsing enemy probes, and engaging in sharp artillery duels. Christmas Day, 1944, proved busy for the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion holding a sector of the front line. A determined German ground attack was repulsed by artillery and mortar fire. Rumors of a pending massive attack circulated, including the probable dropping of German paratroopers behind American lines. Roadblocks were established and passwords changed frequently. Several units, including Combat Command B, were pulled out to perform maintenance on their vehicles and other equipment.

But nothing major happened. With no sign of any imminent attack from the Germans, Seventh Army pulled the 12th Armored Division into reserve on December 30. It remained on three-hour notice to move against any German attack. Replacements for the 62 men killed, 454 wounded, and four missing in action were being integrated into the division as the year ended.

Objective: Herrlisheim

The new year began badly. The anticipated German counteroffensive, known as Operation Nordwind, hit the Seventh Army hard. The German plan was to strike in Alsace and force an American withdrawal, delaying the Allied advance into Germany and giving German scientists more time to develop the so-called “wonder weapons,” which would change the course of the war in Germany’s favor. Knowing that Sixth Army Group had been significantly weakened while covering an extended front, the German planners also believed the attack would relieve some of the pressure on the southern shoulder of the Bulge. The ultimate goal was to split the Seventh Army, clear a way to the fortress city of Metz, and get behind Patton’s Third Army, disrupting the entire Allied line.

After some initial success, the German offensive lost power. Generals Devers and Patch had been quick to react. One of their many moves was to assign the 12th Armored Division to VI Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. Edward “Ted” Brooks. Brooks’ corps had been exposed when the Germans attacked on both flanks and was forced to withdraw. It had no reserves. Both of Seventh Army’s armored divisions, the 12th and 14th, were rushed to VI Corps.

Upon arrival in VI Corps, General Allen was told that a German bridgehead at Gambsheim was the greatest threat to VI Corps and that reducing it was his first objective. On January 8, 1945, Combat Command B, with the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion and 714th Tank Battalion, was ordered to attack the town of Herrlisheim at the center of the German bridgehead.

Attached to the 79th Infantry Division, Combat Command B attacked Herrlisheim from the north on the morning of the 8th, while to the south French troops were to attack Gambsheim. Supported by Company B, 119th Armored Engineers, the actual attack began at 10 am. Intelligence reports indicated there were some 1,200 Germans in the entire pocket, but these estimates were later discovered to be far too low. In fact, Combat Command B was about to attack three regiments of the German 10th SS Panzer Division reinforced by elements of the 553rd Infantry Regiment.

Trapped at the Waterworks

Company B, 714th Tank Battalion followed Company A, 56th Armored Infantry Battalion in the attack, supported by both mortars and assault guns firing from elevated positions outside the town. Company C, 56th Armored Infantry Battalion, with a full complement of 251 officers and men, moved off to protect the flanks of the attack and join up with the French once Herrlisheim had fallen. Before that could be done, the company had to secure a group of small buildings near the Zorn River. These structures contained machinery used to control the flow of water from the Zorn to the Moder River, and they would soon be known simply as the Waterworks. While operating there, an American platoon rounded up several prisoners at a cost of four men killed and several others wounded.

Facing Herrlisheim, the tanks of Company C, 714th Tank Battalion came under fire from enemy artillery and mortars. Attempting to join the infantry, the tanks found that a bridge at the Waterworks was destroyed, halting their advance. Instead, Companies A and C, 714th Tank Battalion took up positions along the Zorn River and tried to support the infantry. Their fire soon ceased, however, when ammunition began to run low. Meanwhile, Companies A and B, 56th Armored Infantry Battalion were supposed to enter the Waterworks, cross the Zorn, and clear Herrlisheim. Despite the early loss of one of the company commanders, the operation proceeded after nightfall. With a crossing accomplished, the Americans surprised a group of about 30 Germans who were moving across open, flat ground, apparently completely unaware that they were within rifle shot of American soldiers. Indeed, so close were the Germans that the Americans had to give orders in whispers so as not to alert the approaching enemy.

Staff Sergeant Charles F. Peischl was first to notice that the Germans had become suspicious. He was also the first American to open fire, followed immediately by the rest of B Company. Most of the Germans were killed or wounded. Before the Americans could verify their success, however, there came orders to withdraw to the Waterworks. The entire 56th Armored Infantry Battalion, reinforced by Company L, 314th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division, assembled there.

The Waterworks soon became a trap for the Germans. In the middle of the night mortars began landing in the courtyard, and movement was heard outside. Hand grenades from German infiltrators were tossed at the American positions. The Americans defended themselves, keeping the Germans at bay, until suddenly two enemy tanks opened fire. Because of an intervening wall, the enemy tanks could not fire down into the sheltering Americans, but they continued to fire at the buildings. Efforts by the 40th Engineer Combat Regiment to replace a destroyed bridge to allow American tanks to cross the Zorn were halted by the German tank fire. One of the two German tanks was knocked out in a gallant action by Private Robert L. Scott of the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion, but increasing German pressure kept the Americans pinned down. Wounded men had to be evacuated by the light tanks of Company D, 714th Tank Battalion. Supplies were brought up the same way.

At daylight the German tanks and most of the enemy infantry withdrew, although more than 100 were trapped and forced to surrender. The 18 self-propelled 105mm howitzers of the supporting 494th Armored Field Artillery Battalion had fired more than 3,700 rounds during the night and into the morning in support of the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion. But so far no American had entered Herrlisheim. While the Americans decided what to do next, the artillery kept up a harassing fire against the outskirts of Herrlisheim, pinning down the several German tanks.

House-to-House in Herrlisheim

On January 9, the Americans renewed their attack on Herrlisheim. Once more the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion led the way with Companies A and B, with Company C in reserve. This time the attack was to begin just before dawn, secure the Waterworks, and then push forward to Herrlisheim by dawn. This would be an infantry battle supported at long range by the tanks of Company B, 714th Tank Battalion, still stymied by a lack of bridges across the Zorn. Captain James Leehman took Company B, 714th Tank Battalion forward, prepared to cross once the Bailey bridge had been completed at the Waterworks. Once across, he was to provide close support to the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion. The two remaining companies of the tank battalion were positioned in fields west of Herrlisheim, firing long-range support.

The plan went awry from the start. As Captain Leehman approached the Waterworks, he saw immediately that no work was being done to install the Bailey bridge. He joined the rest of the 714th Tank Battalion in providing long-range support. In fact, the bridge was not completed that day. In an effort to improve the fire support, Lt. Col. William J. Phelan, commander of the 714th Tank Battalion, ordered Company A to cover Herrlisheim from the north and northeast. However, Company A’s field of fire was blocked by the infantry moving across its front.

The armored infantry had begun its attack on schedule. Moving toward the town they were immediately greeted with heavy machine-gun fire. Then mortar rounds began to fall among them. Another company commander and several soldiers fell. Nevertheless, Company B pushed forward and reached a few of the closest buildings in Herrlisheim. There, enemy fire again stopped the advance. The company altered its direction to seek shelter in a gulley that ran nearby. Perhaps half the company had already been killed or wounded. The light tanks of Company D, 714th Tank Battalion were again pressed into service to evacuate wounded men. The battalion surgeon, Captain William Zimmerman, later credited the light tanks with saving the lives of at least 65 wounded soldiers.

Company A was also hit by German fire but managed to advance with fewer casualties, coming up on Company B’s flank and moving beyond it. Company A advanced halfway to Herrlisheim before halting to await Company B. When it did not appear, orders were received to enter Herrlisheim itself. Company C was ordered to follow Company A, mopping up as it went forward. Companies A and C entered the town at midafternoon and discovered that their radios did not work. A runner was sent to make contact with Company B, which remained pinned down in the fields before the town. Although the armored infantry began to clear the town in house-to-house fighting, the Americans were unable to contact anyone because of the radio problem. Niether Combat Command B nor the two battalion command posts knew anything of what was going on in Herrlisheim.

House-to-house fighting has always been a risky venture. In Herrlisheim each American platoon took a street or row of houses and methodically moved down the line from one to the next. While a few riflemen stood guard outside the house, others went to the rear to check the outhouses. They then went to the first floor windows and fired into the house to discourage snipers or any other enemy inside. Next the door was kicked down and the basement investigated as the GIs worked their way to the top floor. Any civilians encountered were ordered to assemble on the ground floor. In Herrlisheim, several abandoned machine guns and antitank positions were discovered.

The 56th Armored Infantry was making good progress when suddenly Company A came face to face with a German PzKpfw. IV tank. The Americans took cover from the tank’s fire for about half an hour, after which the tank withdrew. As they resumed their advance, several more enemy tanks were observed approaching. With no tanks of their own on this side of the Zorn River, the infantrymen were in trouble. Indeed, although there were signs of progress, the attack was coming apart. Company B was still pinned down and suffering casualties at an alarming rate. Company A faced at least three enemy tanks, and the defenders were showing a more aggressive attitude with snipers infiltrating American lines. Darkness was coming fast, and Company A was ordered to withdraw to the edge of the town and establish a defensive position. Company C moved to aid Company B, which was withdrawn at dark. Captain Francis Drass, commander of Company A, took command of all the infantry elements in Herrlisheim as night fell. As Company B withdrew, it lost its second company commander in less than 12 hours.

Contact Lost With Headquarters

As night fell German artillery fire increased. Enemy infiltration intensified into and beyond the American positions. Company D, 714th Tank Battalion did yeoman’s work in evacuating wounded and prisoners of war. Battalion headquarters of the 56th Armored Infantry sent a specially equipped radio patrol to try to make contact with its embattled companies in Herrlisheim, but it was stopped by German machine-gun fire. A prisoner reported that the companies in Herrlisheim had been wiped out. Captain Elmer Bright, battalion intelligence officer and leader of the patrol, also found some 30 soldiers from the forward companies who had withdrawn. They confirmed the prisoner’s report of the annihilation of their commands. With this information from two sources, Captain Bright turned back.

The night of January 9-10, 1945, was a nightmare in Herrlisheim. The Americans were surrounded and cut off. German patrols wandered throughout the town setting fire to houses they believed were occupied by the Americans. There was no contact with any headquarters. American officers ordered their men to shoot at anything that moved outdoors and told them not to leave their houses for any reason at the risk of getting shot by friendly fire. Sergeant Peischl, still fighting with Company B, later recalled, “The Krauts seemed to have a system of first firing at a building with tracers to mark it, and then blowing it up with a bazooka or antitank gun. Some might have been doped up, for they would come right up to our doors, open them, and yell, ‘Komm heraus!’ We wasted no time in knocking them off.”

Another Day of Fighting

Dawn brought some slight relief. The enemy ceased individual attacks on houses, although mortar fire and snipers continued to take a toll on the Hellcats. As dawn broke over Herrlisheim American medium tanks appeared in town. Captain Leehman’s Company B, 714th Tank Battalion had finally crossed the Zorn on the just completed Bailey bridge. Now the tankers sought contact with the armored infantry companies beleaguered in the town. They knocked out one German tank at point-blank range and began shouting in an attempt to locate the infantrymen. Finally, a lone American appeared and directed the tanks to Company A, 56th Armored Infantry. A quick discussion between the tank and infantry company commanders determined that their force could not hold the town, and the tanks radioed back for permission to withdraw. This request was refused, and the combined force was ordered to hold where it was.

Once again the light tanks brought up supplies and evacuated wounded and prisoners. A thick fog enveloped the area, making movement difficult. One of the light tanks was knocked out by a German antitank gun using the fog for cover. After four round trips by the light tanks, enemy antitank fire became thick on the only route they could use, and so evacuation and resupply ceased. One light tank was trapped in Herrlisheim, two were knocked out, and only one managed to make the last trip successfully. Company B, 119th Armored Engineer Battalion was ordered to move into Herrlisheim and fight as infantry. Joining with the armored infantrymen, the engineers took their places in the bridgehead. That bridgehead remained static throughout January 10, with enemy fire so heavy that any movement out of the protecting houses was impossible. Nevertheless, both battalion commanders came up during the day to take charge of their respective commands.

The 714th Tank Battalion lost two tanks to roving German antitank teams during the day. Its battalion commander was wounded by enemy artillery. Several M8 self-propelled guns tried to get into town to provide support, but they ended up crashing through the thick ice covering the local canals and remained there until nightfall. Continuous German fire and heavy casualties delayed and eventually postponed an attack to complete the conquest of Herrlisheim. The arrival of reinforcements and supplies was halted, and attempts to drop supplies by light plane were prevented due to the fog. The wounded were piling up at the aid stations and battalion command posts. As darkness approached, the two battalions prepared for another long night as tanks paired up with occupied houses to await the next German attack.

German Counterattack on the Seventh Army

Finally, at 2 am on January 11, the order came to withdraw. The movement was completed in orderly fashion. Noise was kept to a minimum, and the tank engines were not started until they were ready to pull out. A friendly artillery barrage covered much of the noise and kept the Germans busy. The night was so dark and the fog so thick that the infantrymen had to hold each other’s belts to avoid getting lost in the gloom. Within an hour the survivors were back across the Zorn. The first battle of Herrlisheim had gone to the Germans.

The Germans were convinced that the Seventh Army was weak and that another strong push would bring success. Indeed, the collection of American and French Army units containing the Gambsheim bridgehead lent credence to that belief. Surrounding the German enclave were the 314th Infantry Regiment (79th Infantry Division), Combat Command B of the 14th Armored Division, the 232nd Infantry Regiment (42nd Infantry Division/Task Force Linden), and elements of the French 3rd Algerian Infantry Division. To overcome what the Germans viewed as a miscellaneous collection of forces, they committed their experienced 21st Panzer and 25th Panzergrenadier Divisions to secure the Gambsheim bridgehead. General Brooks soon found his VI Corps fighting for its life against three attacks from three directions. Several days of bitter fighting ensued.

By January 16, the German attack had pushed VI Corps back along the west bank of the Rhine. Another attack was expected, but contrary to the expectations of Generals Patch and Brooks, it did not come against the main American line. Instead, the Germans hit the western flank held by the 12th Armored Division. The Hellcats had been ordered to seize Herrlisheim to cut the principal German north-south communication line with the Gambsheim bridgehead. They had moved into position and launched their first attack, which failed when far more Germans were found to be defending the town than General Allen had been led to believe. Normally a job for an infantry division, the Hellcats were the sole reserve available to Seventh Army, and so they had drawn the short straw.

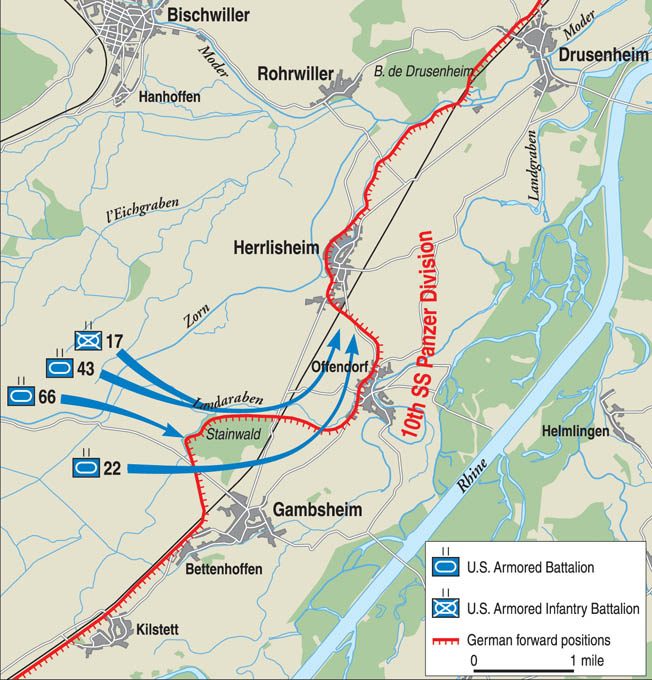

Undeterred, General Allen ordered both Combat Commands A and B to renew the attack. This time Major James W. Logan’s 17th Armored Infantry Battalion would attack Herrlisheim from the south while Lt. Col. Scott Hall’s 43rd Tank Battalion skirted the east end of the town to surround it. The objective of Combat Command B was to clear the Stainwald Woods and the town of Offendorf, which flanked Herrlisheim. The attack was to begin on January 17.

The 43rd Tank Battalion Disappears Into Thin Air

Once again the armored infantrymen were able to enter the town and begin clearing it only to encounter increasingly stronger German defenses as they went along. The 17th Armored Infantry Battalion soon found itself surrounded in the town, cut off, and forced to withdraw despite strong artillery support, losing a number of prisoners. Major Logan’s final message to headquarters at about 4 am simply reported, “I guess this is it,” as his battalion was overrun. But what had happened to their support, the 43rd Tank Battalion? It would be months before anyone discovered exactly what had happened to the battalion, which had never returned to American lines.

The 43rd Tank Battalion, under the command of Lt. Col. Scott Hall (some sources give Lt. Col. Nicholas Novosel as commander at this time), had fought at Offendorf the day before, where it had lost 12 tanks to enemy action. As planned, the 43rd followed the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion to the outskirts of Herrlisheim and then turned off on its flanking mission to the east and north. Radio contact between the two units of Combat Command A was lost at 10 that morning. At about noon on January 17, the commanding officer radioed his executive officer at Combat Command A, “Things are plenty hot.” Some garbled messages came in later, but no one could understand them or determine where the battalion was located. One message from the battalion operations officer reported incoming German antitank fire. The last message from the battalion commander reported the unit’s location as east of Herrlisheim, and a short time later a brief message was received reporting that the battalion commander’s tank had been knocked out. Nothing else was ever heard from the 43rd Tank Battalion. Some 29 American medium tanks and their crews had simply vanished.

While the battle still raged in Herrlisheim, the supply and administrative units of Combat Command A searched in vain for some sign of the 43rd Tank Battalion. Despite being overrun, many of the 17th Armored infantrymen had managed to escape from Herrlisheim, but not one man returned from the flanking maneuver of the 43rd Tank Battalion.

Piecing Together the Fate of the 43rd

It was not until a day later that the mystery began to clear. An artillery observer flying over the battlefield on January 18 reported several destroyed American tanks on the eastern outskirts of Herrlisheim. Continuing on, he found two more groups of destroyed American tanks in the area. These tanks were reported to be deployed in a circular defensive formation. Some were painted white while others had been burned black. General Allen immediately ordered a rescue attempt, but closer observation reported no sign of movement from the American tanks and also recorded a strong German presence in the immediate area. With no evidence that there was anyone left to rescue, the attempt was cancelled.

Intelligence reports later added to solving the mystery of the lost battalion. Information received after the battle revealed that the attack of Combat Command A had unexpectedly run into the counterattack of the 10th SS Panzer Division, which had been ordered to enlarge the bridgehead. That evening German radio announced that an American lieutenant colonel and 300 of his men had been taken prisoner at Herrlisheim and that 50 American tanks had been captured or destroyed. General Allen and his staff could only speculate that the 43rd Tank Battalion had run into a well-planned German ambush and been annihilated. With no fresh forces left to him, General Brooks ordered a withdrawal of his VI Corps. Herrlishiem would have to wait.

In late February 1945, more information on the lost battalion was found. The 12th Armored Division’s graves registration report dated February 23 indicates that the 43rd Tank Battalion tanks that were found knocked out in the town had been hit by panzerfausts—infantry-held antitank weapons—while the tanks on the eastern edge of the town had been devastated by high-velocity cannons. The investigators found many German antitank positions indicating that both 75mm and 88mm antitank guns had been positioned just outside the town. The conclusion was drawn that the battalion had entered the town, been struck by infantry armed with antitank weapons, and had then withdrawn to the outskirts of the town, where it encountered a barrage of antitank fire. Some 28 destroyed tanks were identified. Contrary to the German report, the bodies of the battalion commander and many of his men were also identified. The report went on to state that it appeared from tracks and other indicators that perhaps four American tanks had been captured intact and removed by the Germans.

The End of Operation Nordwind

The Hellcats were not yet done with Herrlisheim. On January 18, a task force consisting of Company B, 66th Armored Infantry Battalion and Company B, 23rd Tank Battalion made an abortive attack to try to reach any survivors of the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion who might be in town. On the flank, Combat Command B made no headway against the Germans. That evening orders came for the division to withdraw to the west side of the Zorn to coordinate with a general withdrawal of VI Corps. Some small German counterattacks were repulsed once the division had settled into its new positions. The next day the Hellcats were relieved by the 36th Infantry Division. The Hellcats moved to Strasbourg for a rest before returning to combat with the French First Army.

Ironically, just a few days after the Hellcats were relieved, the Germans decided that they had no chance to break through Seventh Army and called off their Nordwind offensive. Their best remaining combat units were shifted to the Eastern Front, leaving behind some 23,000 casualties against American losses of 14,000. Indeed, the Seventh Army was stronger than ever with the arrival of the 42nd, 63rd, and 70th Infantry Divisions at the front and the veteran 101st Airborne Division held in reserve.

The Lessons of the Battle of Herrlisheim

The Herrlisheim battle pointed out lessons that had been learned earlier in the battles for Normandy, northern France, and Brittany. Inexperienced combat divisions often had to learn in combat how to maneuver their tank and infantry assets. In Herrlisheim the new 12th Armored Division too often separated its infantry and armor, particularly in street fighting. A good infantry-tank team was essential to clearing a defended town. Tanks alone in narrow streets with overhanging roofs were sitting ducks for German antitank teams. Similarly, infantrymen could not adequately clear a town without close armored support. At Herrlisheim, the armored infantry repeatedly went into the town without accompanying armor. Likewise, the attack of the 43rd Tank Battalion had no infantry support, which might have pushed the German antitank gunners back far enough to enable the combined force to gain a foothold on the eastern end of Herrlisheim. However, for an inexperienced combat unit the Hellcats gave as good as they took.

By the end of January 1945, the Seventh Army was once again on the attack. General Brooks’ VI Corps was ordered to eliminate the Gambsheim bridgehead. He sent the 36th Infantry Division, supported by Combat Command B of the 14th Armored Division, to clear the zone. Miserable weather restricted the armor to a few good roads, and strong German defenses delayed the advance repeatedly. Nevertheless, the bridgehead was cleared by February 11, and American troops finally occupied Herrlisheim.

The Hellcats went on to take part in the clearing of the Colmar Pocket in February with the French First Army and then attacked through the lines of the 94th Infantry Division in March, reaching the Rhine north of Mannheim, Germany, on March 20, 1945. They crossed the Rhine at Worms and fought their way eastward through southern Germany until they reached Schweinfurt. Town after town fell to the now highly experienced combat division until it forced a crossing of the Danube River.

The Hellcats were in Austria, moving on Innsbruck, when the war ended. Months of fighting had cost them 724 killed and 2,416 wounded in combat. Many of these casualties had been incurred far to the west at a town called Herrlisheim.

They surrendered to Erwin Bachman with 21 fully fueled and armed tanks along with about 20 german prisoners they were holding. At gun point, he forced the Americans to drive their tanks to the 10th Panzer division as a belated christmas present…

Obersturmführer Bachmann from the 10th SS Regiment Frundsberg got the Knights Cross for his actions. He captured 12 M4A3 75W and destroyed 9 others from the 43rd Tank Battalion with only two panthers. Those US tanks soon saw combat under German markings on the Eastern front later. None survived.

This article is simply not complete without a reference to the action of Obersturmführer Bachmann which marks an end of the unfortunate 43rd whose men’s morale just collapsed. Reading this article an uninformed person would assume the 43rd fought to the last man; they did not. Half of the battalion was destroyed by 1 man on foot and 2 tanks, while the other half just surrendered together with their tanks. No reason to hide or pretend; things like that happen in war. After all we are all just humans.

Is there more information out there to read and study? My father was in the 119th armored engineers, he was captured at some point leading to or during the Herrlisheim battle.

Steve,

There is a LOT more information available. The 119th was heavily involved in Herrlisheim and indeed had a record to be proud of. We have several Hellcat veterans and a lot of 2d/3d generation decendants who can help you sort out your father’s story.

Please email me, will be glad to help you. There are a lot of personal accounts on the website for the 12th Armored Division Museum and some very detailed analysis of the Herrlisheim battle.

https://www.12tharmoreddivisionmuseum.com/

https://c13cda39-9e5e-48b5-8b73-b104bf34d117.filesusr.com/ugd/c0865a_885dcde51ae44d3e9b6bc8aa78f1ae92.pdf

Also you are welcome to join us with the 12th Armored Division Association – to include joining us at the 75th Annual Reunion in New Orleans (at the National WWII Museum) July 14-18 2021.

https://sites.google.com/view/12tharmoreddivisionassociation

Steve — dont put this off any more. I waited too late and missed the chance to meet several men who served with my father in the 56th Armored Infantry. But it has been such a privilege to meet and become friends with other Hellcats. Contact us and we will help you find your story.

Steve – Paul Rivette of the legacy 56th AIB gave you very valuable information on 7/9/2021.

I would like to share some more.

My dad Luke Zilles was in the 17th AIB Company C, 1st Platoon, and he was also near Herrlisheim with the 119th Armored Engineers. He was wounded near the “waterworks”.

If you have not located your Dad already, I may have found him (if it is indeed him) in a POW list that appears on the Texas Archives and on the Museum Website.

These are the 5 men listed:

George Aswald, 119th C

Richard W. Fender 119th (No Company Listed)

Floyd M. Kohr, 119th C

Donald T. McMullen 119th C

Vernon Pence, 119th C

After we did much work to ascertain that the 12th Armored Museum site provides a Roster that is missing many Soldiers and details (including these 5 men), a Programmer and I have created an interface to a Roster of the 12th Armored we are trying to make much more complete, more “human” and more user friendly.

If one of these men above is your Dad, and you put your last name into the interface, it will bring up a page which explores the Roster and the Texas Archives for his name, as well as NARA, the database of Army inductees. If he is one of the men above, it will find the name on our new website.

The website is called “Humans of the 12th Armored”, and it is just going up now. Eventually we hope to provide links to web pages by Soldier name (Oral Histories, Remembrance Web Pages, etc.). We will also have a message board for folks to share information with each other. The website is:

https://12th-armored.directory/

There are also excellent “Oral Histories” of the 12th Armored on the new Museum website, but, unfortunately, while their old website had 10 for the 119th (including Floyd M. Kohr, the POW mentioned above), the new one only has 2 (and Mr. Kohr’s is not there).

Interestingly, while we have 2 “Floyd Kohr”‘s on our Roster (one in the 66th and one the 119th), the Museum has none. They do say the list is “Not Comprehensive”.

We have been trying since January 2021 to find out when the other Oral Histories will be added (187 are missing), but so far have not gotten very far. Perhaps if more voices make the request, it will happen. I am sure the 119th C Mr. Kohr knew your Dad, as they were both POW’s.

My email is kzilles@realprop.org if you have any questions. Good Luck!

My Uncle Simon Bacola was a member of the 12th Armored Division. In two separate incidents December 1944 and January 16, 1945 he crawled from a safe position to render first aid to fellow platoon members and on 16 January 1945 was last see rendering First-Aid to his Platoon leader. He won The Silver Star Oak leaf Cluster, Purple Heart and State of New York Medal. He was killed in action defending his country at 22 years old. I never had the privilege of knowing my Uncle but, his memory is held in my heart forever. He was a true

Hellcat.

I am doing research on my 2nd great-uncle James Porter Robinson- His application for Military Veteran Headstone lists he was in CO. C 56 Armd Inf Bat/ 12 Arm Div. He was shot in France and died at 24 yrs old 3 months before he was to return home. He is buried in his hometown in Runnels County, TX. There is another James P. Robinson of Texas and I’m having trouble narrowing down what really happened to him. So I entered the Unit name and went from there and found this website. There is a unit of the same I listed on the Portal to TX History and my gg-uncle isn’t listed. I really wish to honor him and not let him be overlooked. He never got to marry like so many. He had other brothers that served and came home. Any suggestions and would this article be the correct information for the unit I wrote down? I would appreciate any help. Thank you.