By Robert E. Cray, Jr.

“We are going to have Christ’s own bitter time to win it, if, when, and ever,” commented Ernest Hemingway to his friend and editor, Charles Scribner, at the start of World War II. A celebrated author, Hemingway considered the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reprehensible, at one point asserting that Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox should have been relieved of duty, while ranking Army and Navy commanders at Oahu deserved to be shot. Hemingway was nothing if not opinionated.

But the man who penned such well-received novels as A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls could wield a sword too, in this instance, his yacht, the Pilar. In 1942 and 1943 Hemingway, supplied with an assortment of machine guns, bazookas, and grenades courtesy of the United States government, patrolled the Caribbean Sea. If all went well, Hemingway hoped to lure a German U-boat close to Pilar, before disabling or sinking it with a fusillade of firepower. The marauding German submarines had roamed the Caribbean and sunk thousands of tons of Allied shipping. Hemingway intended to make the hunters the hunted. It was a daring, perhaps foolhardy, plan, in keeping with Hemingway’s own outsized personality.

A Writer Goes to Sea

Ernest Hemingway began life far from the sea in America’s heartland. Born in affluent Oak Park, Illinois, in 1899, Hemingway learned to hunt and fish in the Upper Midwest, his sailing restricted to small freshwater craft. In World War I Hemingway served in an American Red Cross unit on the Italian front, suffered injury from artillery shell fragments, and earned medals from the Italian government. Literary prominence came while he lived in France in the 1920s, with the publication of In Our Time, a collection of short stories, and even more with The Sun Also Rises, a novel about American expatriates in France and Spain. Hemingway’s relocation to Key West, Florida, in 1928 introduced him to the Gulf Stream waters of the Caribbean, a venue that would figure prominently in his later fiction and mark the landsman’s transformation into a sailor.

The Pilar provided the impetus. Hemingway purchased the cabin cruiser from the Wheeler Shipyard in Brooklyn, New York, in 1934 for $7,500. Named after Our Lady of the Pilar at Zarogoza in Spain as well as his second wife, Pauline, the ship arrived by rail in Miami that spring. The black hull built of American oak had a green roof and mahogany cockpit; it was 38 feet long with an 11-foot beam and a draft of three feet, two inches. Powered by a 75-horsepower Chrysler engine and a 40-horsepower Lycorying engine for trolling, the Pilar could reach a top speed of 16 knots and cruise to a range of 500 miles.

Hemingway customized Pilar by lowering the transom 12 inches to pull in fish and increasing the number of gas tanks. Sailing Pilar to Key West, he inspected the controls and checked the engines and was thoroughly pleased. The “boat is marvelous,” he wrote a friend. As his son, Gregory, remarked, Pilar ranked among the great loves of Hemingway’s life, just behind his children, wives, and cats.

The six-bunk vessel hosted numerous sports fishing parties, and the New York Times reported on the author and his guests. Writers and nonwriters, men and women could see the proud skipper show off his skills. Fishing occasionally became a blood sport. Once, while gaffing a shark in 1935, the gaff broke, striking Hemingway on the hand holding his pistol, which had been intended to dispatch the shark. Instead, the bullets bounced off the brass railing and through Hemingway’s two calves, necessitating medical attention. A few days later Hemingway got his revenge. Sharks that descended upon a huge tuna caught by Hemingway started thrashing in blood-stained water, machine-gunned by an angry Hemingway. Pilar would become, in the words of a Hemingway biographer, a “kind of floating whore house and rum factory as well as a fishing boat.”

Pilar’s owner sought adventure, especially sports fishing, and was eager to try his luck. Anything from sailfish to marlin to tuna attracted Hemingway. From Key West it was a short hop to Bimini and Cuba, where even bigger fish swam. The run between Key West and Cuba took roughly four hours, and the trip provided Hemingway material for To Have and Have Not, a tale of a rum runner. The sea now colored his prose.

Hemingway’s “Crook Factory”

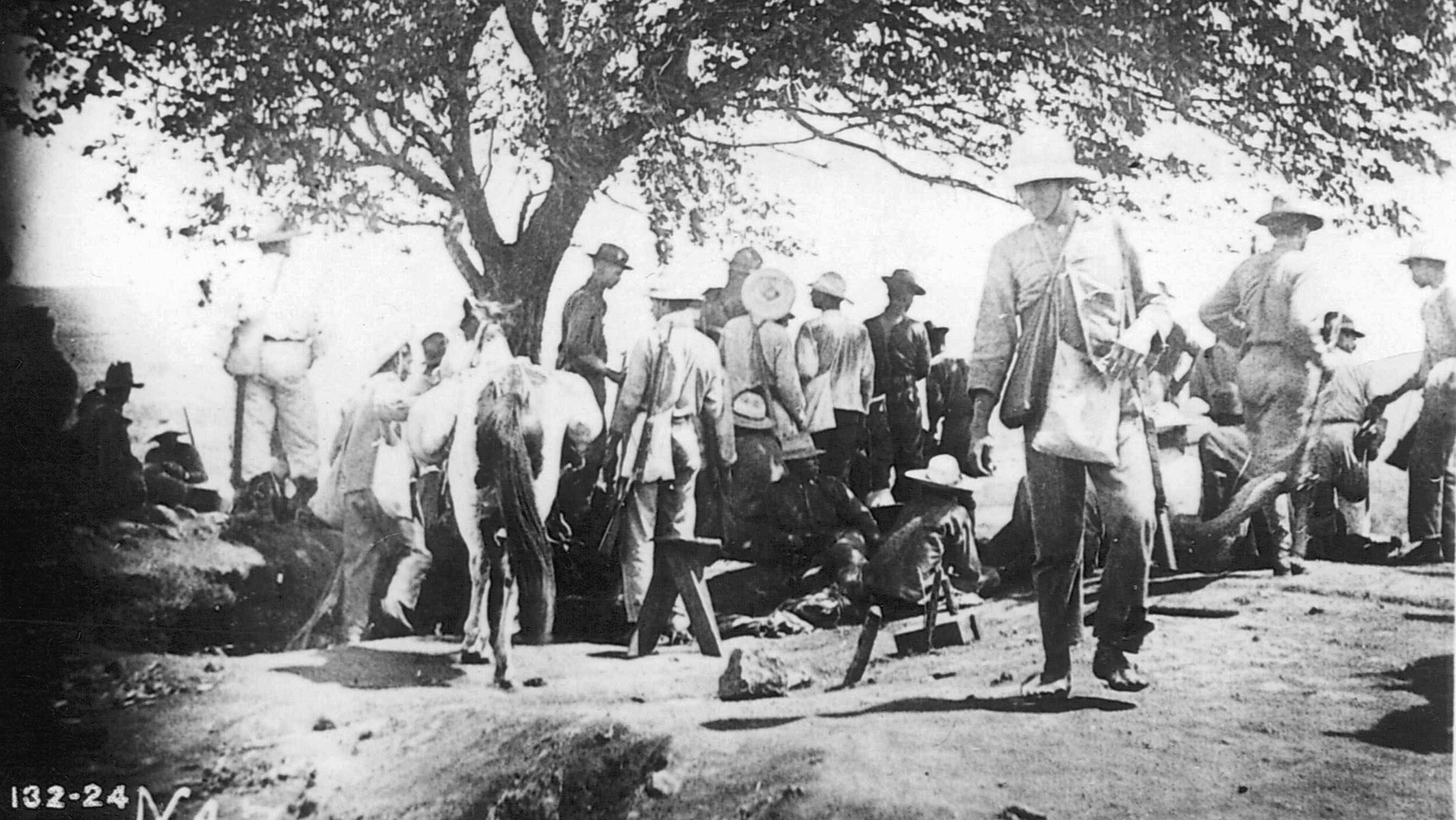

Hemingway relocated to Cuba by 1939. The following year he purchased Finca Vigia, a villa outside Havana that he had previously rented, and watched the world situation deteriorate. Having already covered the Spanish Civil War, at times exceeding his role as a wartime journalist by bearing arms, Hemingway seemingly relished risks. In war-torn China, assaulted by the invading Japanese, Hemingway passed along information in 1941 to the United States government, reporting to an Army Intelligence team in Manila. In May, the Office of Naval Intelligence debriefed Hemingway, and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau heard his report.

The U.S. entry into World War II prompted Hemingway to oversee an ad hoc intelligence operation in Havana in 1942, convinced that Falangists (Spanish Fascists) residing in Cuba represented a potential fifth column. The Finca’s guest house became the headquarters of Hemingway’s counterintelligence unit, the “crook factory” as he termed it, designed to keep tabs on suspects. The American ambassador, Spruille Braden, appreciative of Hemingway’s efforts, asserted that he “built up an excellent organization and did an A-one job.” Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn, was less convinced, critical of the crook factory’s noisy nighttime parties and heavy drinking at the Finca. It seemed a strange way to conduct spying.

Going After a Big Fish

Offshore in the Caribbean Sea, U-boats were making even greater noise in a rich hunting ground that offered an array of pickings. Such cities as Galveston, New Orleans, and Houston, all of them major oil ports, attracted German naval interest. Aruba was the site of the biggest oil refinery in the world, a prime source of diesel, aviation fuel, kerosene, gasoline, and fuel oil, all of them vital to the Allied war effort.

On February 16, 1942, U-boats descended on Aruba, sinking tankers and shelling the refinery. Merchant ships carrying bauxite—a critical component for aluminum production—from British and Dutch Guiana provided other tempting targets. Sub attacks in 1942 at the height of the German Caribbean campaign sank 263 ships, exceeding total losses on the North Atlantic convoy route.

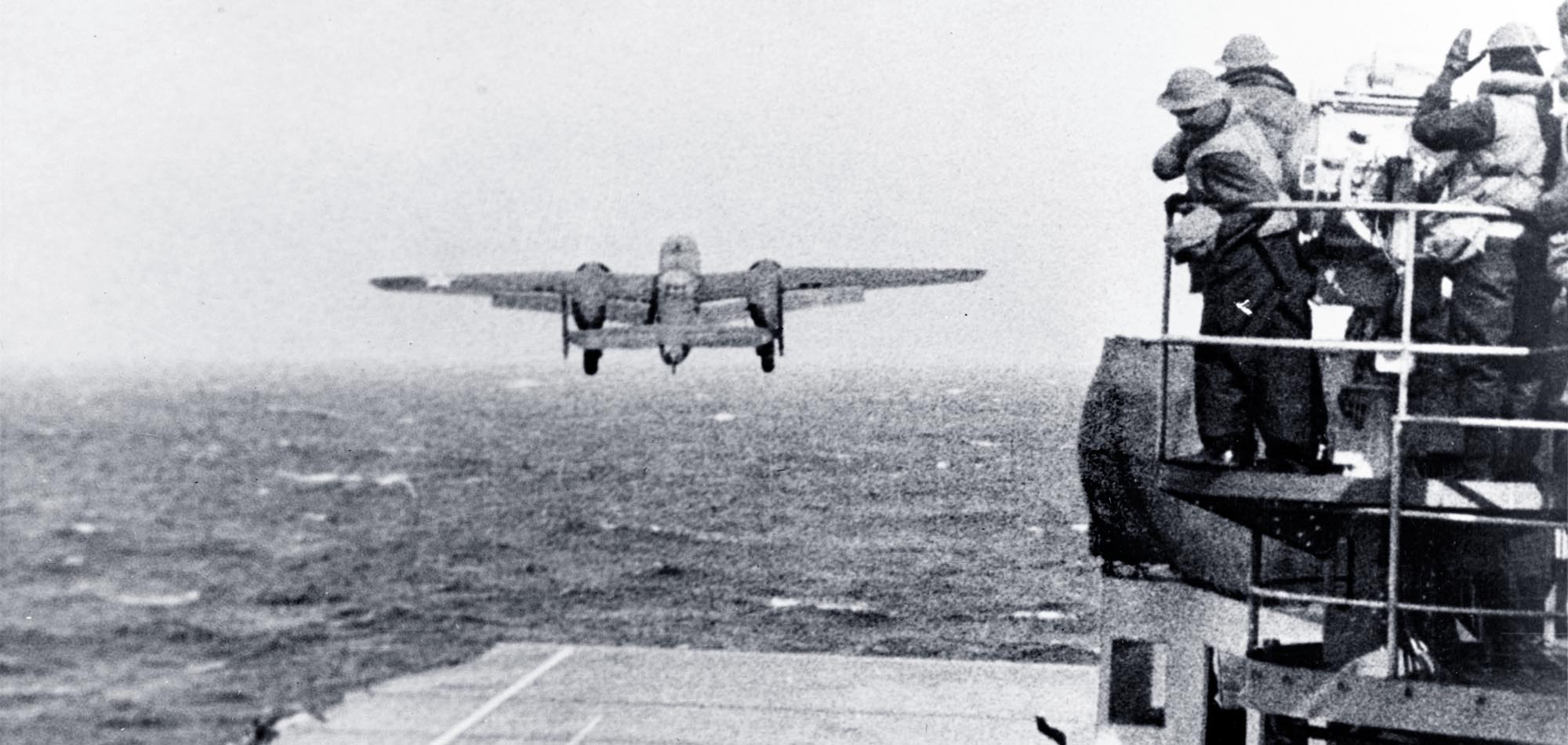

In Cuba, a restless Hemingway decided to equip Pilar as a sub chaser. Fascinated by the exploits of Q-ships, disguised to deceive U-boats into surfacing and then attack them during World War I, Hemingway saw possibilities of a U-boat capture by Pilar. British mariners in the Great War had disguised and armed civilian vessels, luring U-boats by outright deceit before pouncing with quickly uncovered weaponry. A camouflaged Pilar posing as a fishing boat, while in reality armed to the teeth, could continue the tradition of naval deception.

The fact that U-boats sometimes surfaced to confiscate fish and water from civilian vessels gave the venture a thin veneer of plausibility. Once a U-boat was crippled, Hemingway could radio for naval assistance, finish the job, and perhaps secure valuable German codebooks.

Other motivations may have influenced Hemingway, too. Journalists back home wondered about his contribution, or perceived lack thereof, to the war effort. A man wounded in World War I who also bore arms during the Spanish Civil War appeared strangely inactive. Nor was Hemingway able to publicize his crook factory activities beyond a few intimates. Intelligence work ashore was lonely, often bereft of notice. By definition, if not always in reality, Hemingway’s operation had to be kept quiet, at least to the press.

Yet the author eventually grew bored. Hemingway found typing reports tedious work. Where was the danger in such activity? Capturing a U-boat offered more excitement. It could even be trumpeted in a blaze of publicity loud enough to silence any critics. If not, Hemingway would still have the satisfaction of an independent command aboard his beloved Pilar.

A “Doubting Thomason”

Hemingway approached Ambassador Braden to help equip Pilar. According to Braden, Hemingway said, “I can really have myself a party provided you will get me a bazooka to punch holes in the side of a submarine, machine guns to mow down the people on the deck, and hand grenades to lob down the conning tower.”

Braden could not say no. Hemingway was, after all, a famous American author. If Hemingway acquired hard-to-get rationed gasoline, naval equipment, guns, and supplies, it could all be chalked up to the war effort. Besides, Secretary Knox had asked East Coast yachtsmen to employ their vessels against the German Navy. Should not Hemingway be permitted to play his own role?

Pilar’s wooden structure, too fragile to mount the .50-caliber machine guns Hemingway wanted, left the crew with light machine guns. Bazookas and grenades carefully hidden below deck complemented the arsenal. Hemingway recruited Cubans, Spaniards, and Americans, including for a time his two young sons, Patrick and Gregory, along with a Marine sergeant, Don Saxon, sent by the government to work the radio. Critics were airily swept aside. When the chief of naval intelligence for Central America, U.S. Marine Colonel John W. Thomason, certain that no German submarine would venture near Pilar, urged Hemingway to modify his plan, the famous author dismissed him as a “doubting Thomason.”

Searching for U-boats

So how would Hemingway proceed? The first task was to reconnoiter and patrol the sea-lanes in the Caribbean near Cuba, noting any surfaced U-boat and reporting it to the Navy. Listening to German naval chatter on the radio might give Pilar’s crew other clues to the enemy’s activities. Pilar could also venture into isolated cays, searching for German munitions and armaments, or perhaps discover caches of food and water placed there by Axis sympathizers. Naturally, the coup de grace, the capture of a German submarine, remained foremost in Hemingway’s thoughts. Several years after the war, he confidently informed his friend A.E. Hotchner, “A U-boat not on alert could have been taken by our plan of attack.”

His enthusiasm was unshakable.

To facilitate the sub attack, the Pilar carried atop its flying bridge a specially made bomb. The coffin-shaped explosive had handles enabling two strong men to toss it into the U-boat’s conning tower, presumably after gunfire had mowed down German crewmen on deck. It would certainly be a tricky operation. The submarine tower would be slightly higher than Pilar’s bridge, and the bomb barely small enough to fit down the narrow conning tower hatch. Once thrown, the explosive might well miss the hatch, sending fragments toward Hemingway and his crew, a point that a concerned Martha Gellhorn tried to impress upon her stubborn husband.

In 1942, Hemingway took short cruises, returning to Havana at night to deliver his reports. By 1943, he extended his range from a base camp on Cayo Confites, a flat sandy isle with a few palm trees where Hemingway anchored Pilar. Supplies of fuel, food, water, ice, and alcohol would be obtained from a naval facility. Daily patrols involved monitoring sea-lanes, spotting vessels, exploring tiny islands and cays, and watching for anything unusual. When exploring shallow waters, care had to be taken to avoid harming Pilar’s hull. Running aground might also leave them easy prey for the enemy.

A Fruitless Mission

Actual results proved spotty. For instance, in December 1942, Pilar observed a Spanish vessel, the freighter Marques de Comillas, which appeared to have a smaller ship, possibly a submarine, in tow. Hemingway tried to follow the sub before it faded from sight, having radioed naval authorities about the suspicious transaction. In Havana, the ship was stopped, the crew and passengers questioned by FBI agents. No one admitted seeing a sub. Listening to U-boat chatter via radio became an exercise in futility. No one spoke fluent German, making the task all the more difficult.

Nevertheless, Gregory Hemingway, Ernest’s youngest son, retained fond memories of life aboard Pilar. That Hemingway employed his sons in the operation says something about his parenting skills. At least one biographer, Kenneth Lynn, has suggested that Hemingway’s sub chasing more resembled a lark than a serious naval patrol. Still, from 11-year-old Gregory’s perspective the enterprise was a high seas adventure. Armed men took position in the stern and the bow, while he, the youngest member of a multinational crew, held a rifle.

Escapades ashore furnished additional excitement. At one point, while searching caves for German supplies, a crewman ordered Gregory and his older brother Patrick through a narrow passage. Gregory was at first overjoyed and later dejected to find that a few bottles of German beer had not been abandoned by a U-boat crew. It was likely that American tourists had tossed them away.

Gregory Hemingway’s sea adventure reached a climax near the end of his holiday. Pilar had actually sighted a U-boat 1,000 yards away.

“Battle stations,” roared his father.

The crew scrambled into position, with brother Patrick holding a .303 Lee-Enfield rifle and Gregory clutching his mother’s old gun, a Mannlicher Schoenauer rifle. Crewmen unmoored the bomb from the flying bridge. However, the U-boat sped away uninterested in the disguised fishing boat. The angry crew hurled insults at the Germans. As for the phlegmatic Papa Hemingway, young Gregory distinctly remembered his mocking speech about the episode, capped by telling his son to fix him a gin and tonic.

“The Ethylic Department”

Gellhorn developed a different perspective about her husband’s adventure. She was a seasoned journalist who fell in love with Hemingway during the Spanish Civil War. Dangerous assignments rarely fazed her. Sheer foolishness was something else. She had cautioned Hemingway about the plan’s shortcomings to no avail. Having seen the deterioration of Hemingway’s crook-factory spy ring, Gellhorn’s skepticism of the sub-chasing scheme mounted. She eventually concluded that Hemingway’s adventure was an excuse to drink at sea and hurl grenades at buoys.

Hemingway never shared his third wife’s opinion. To him, the Pilar patrols were serious business.

He informed Martha in early 1943: “I have so much to tell but have gotten so used to writing letters that will be censored that I have lost ability to put anything down.”

Even so, certain issues, namely alcohol, appeared noteworthy enough to mention. Drinking remained a popular Hemingway pastime, and two open shelves down in Pilar’s cabin, referred to by Hemingway as “The Ethylic Department,” housed his liquor supply. His shipmates drank freely when alcohol was available, but their skipper modestly made do with three and sometimes only two and a half drinks per day. He hoped to inspire Sergeant Saxon, their hard-drinking radio man, to cut back. Getting Saxon down to four drinks a day, instead of his usual 20, was a significant victory.

Too little booze could still rattle the normally hard-drinking author. By the summer of 1943, Hemingway complained to Martha that going without gin for a week and wine for six days was a wartime sacrifice. In response, he resorted to rum. When stirred with grapefruit juice, lime, and ice, he informed Martha, it made a decent cocktail, but a seven-day trip with only rum cocktails constituted a hardship.

Hemingway’s crew felt the strain as well. Two of them muttered about the absence of spirits, according to young Gregory, threatening to seize the helm and turn the ship to the nearest bar. No mutiny occurred.

By July 1943, the U-boat war in the Caribbean Sea was winding down. A coded message ordered Pilar home. The men were worn, and the boat was in bad shape. Pilar’s drive shaft had to be realigned, and the engine gaskets and rings needed replacing. Although Hemingway took a repaired Pilar out for short cruises in the autumn, his role as a sub chaser was effectively over. Perhaps it was just as well. A growing sense of frustration gnawed at him.

In his only known letter written aboard Pilar at sea, Hemingway informed a friend on June 30, 1943: “I would have written you Old Mike many times but there is nothing that I know or that could be of interest that I can write. Been that way for a year or more and working like a bastard all the time. Wish I could see you though and that we could have a few drinks and talk things over.”

Wartime censorship no doubt kept Hemingway from revealing Pilar’s covert mission, but the author’s disgruntled tone was plain enough.

Did Hemingway’s Sub-Chasing Scheme Really Have a Reasonable Chance of Success?

The answer appears to be no. From the start, Pilar was overmatched; her crew, however determined, relied upon light machine guns, grenades, and bazookas, while German U-boats typically had an 88mm deck gun complemented by lighter weapons. Some U-boats carried 105mm deck guns. A single shell from either of these would have destroyed Pilar.

In addition, most U-boats stayed submerged during the day, surfacing to charge their batteries at night when Pilar was in port. Pilar lacked sonar and radar, useful implements for submarine warfare, making Hemingway’s plan more of a long shot. He gambled that Pilar would attract a passing sub’s curiosity, a slender straw of hope in the overall balance of Caribbean warfare.

Contemporaries remained divided over Hemingway’s sub chasing. The only Cuban to capture a U-boat off his country’s waters openly scoffed at the author’s plan. Captain Mario Raminez Delgado dubbed Hemingway “a playboy who hunted submarines off the Cuban coast as a whim.”

Raminez Delgado at least had action to back up his statement, Hemingway had none.

Yet, Hemingway had monitored the sea-lanes and sent in reports, much as any conscientious navy man might do, expending considerable time and effort. His contribution, if more well intentioned than substantive, convinced Ambassador Braden that the service rendered was important. In Hemingway’s own mind, he had gathered valuable naval intelligence, with Pilar paying the price in hard usage and repairs.

We do know what Ernest Hemingway would have preferred. As a novelist whose personal experience colored his art, he mentally filed away the sub hunt experience in hopes of reproducing in print his World War II sea adventure. In his novel Islands in the Stream, published after his death, Hemingway’s main character, Thomas Hudson, is an artist turned sub chaser patrolling the Caribbean. Word of a German crew escaped off a destroyed U-boat sends Hudson and his men in in pursuit. The two forces meet, leaving Hudson injured and dying, but the Germans have been killed.

Hemingway the novelist got the story he wanted, even if Hemingway the sub chaser failed to net his prey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments