By Kevin M. Hymel

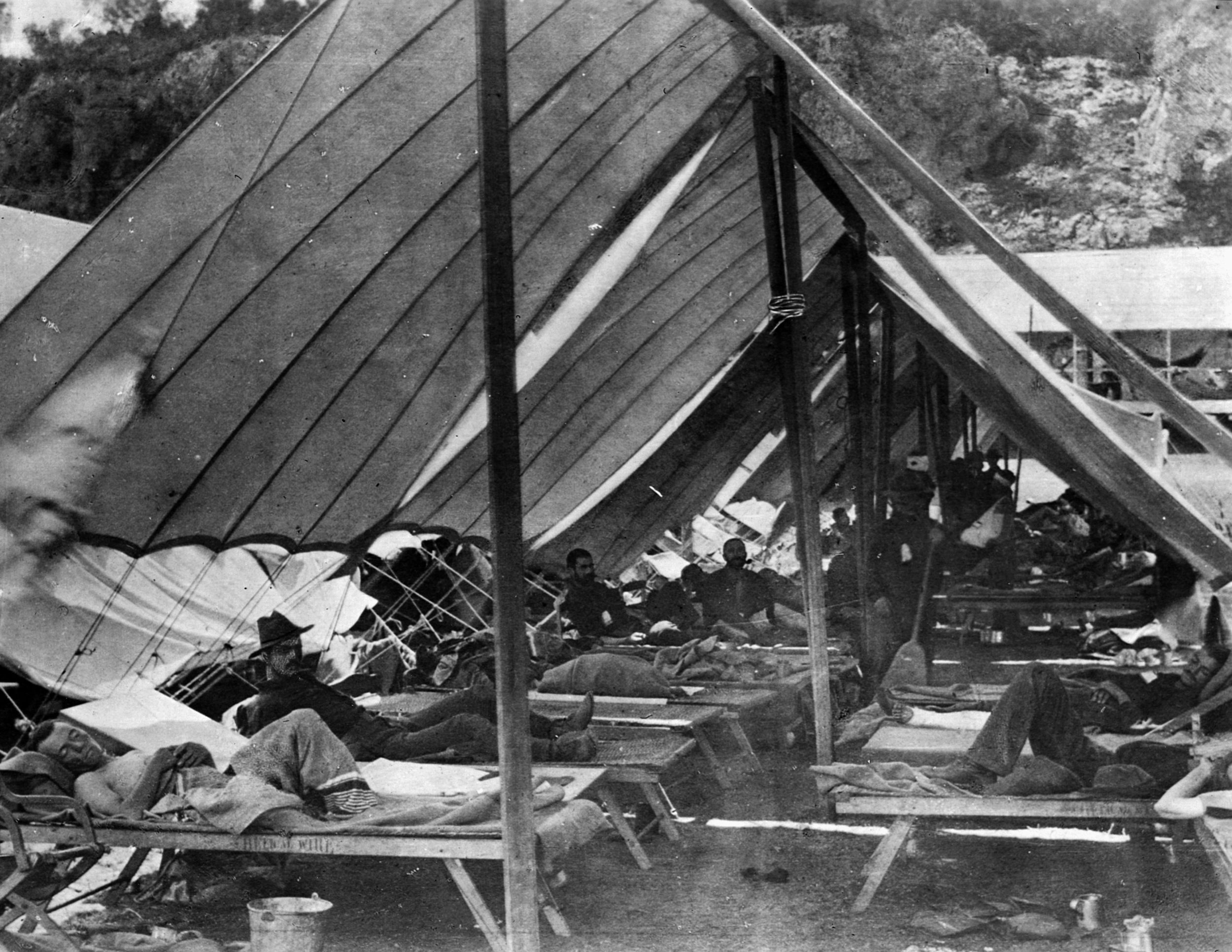

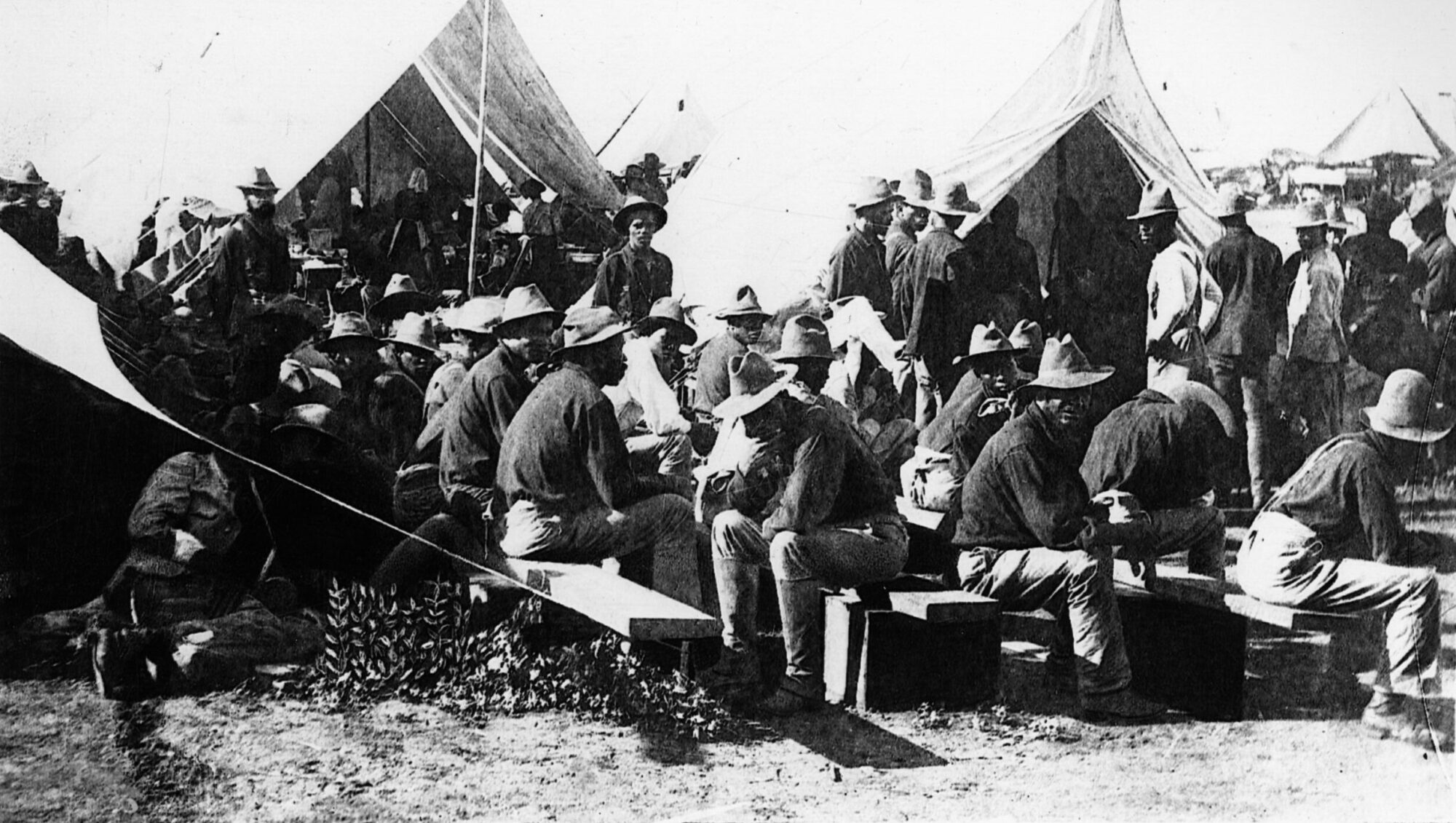

The khaki-clad soldiers wounded in the steaming jungles of Cuba during the Spanish-American War had distinct advantages over their Civil War brethren. Soldiers of the Blue and Gray suffered through amputations performed with unwashed instruments. Thirty-three years later, modern medicine had caught up to the battlefield. X-ray machines enabled doctors to extract bullets and shrapnel without digging around in their patients; aseptic surgery reduced infections; and sanitation systems prevented diseases from spreading in tightly packed camps.

But the system was not perfect. For all the advances in medicine there was one obstacle the doctors could not overcome: American officers. Commanders, accustomed to the rampant disease of the Civil War, accepted sickness as part of war. They refused to listen to camp doctors who insisted on keeping camps clean. By the officers’ logic, the doctors’ job was to treat patients brought to their hospitals, not to tell the officers how to run their camps. To make matters worse, the worst men in the Army, usually the laziest or problem soldiers, were assigned as nurses, while women were barred from military hospitals. Male nurses tended to spread disease by ignoring their patients, dumping out bedpans in front of the disease wards, and generally obstructing doctors more than helping them.

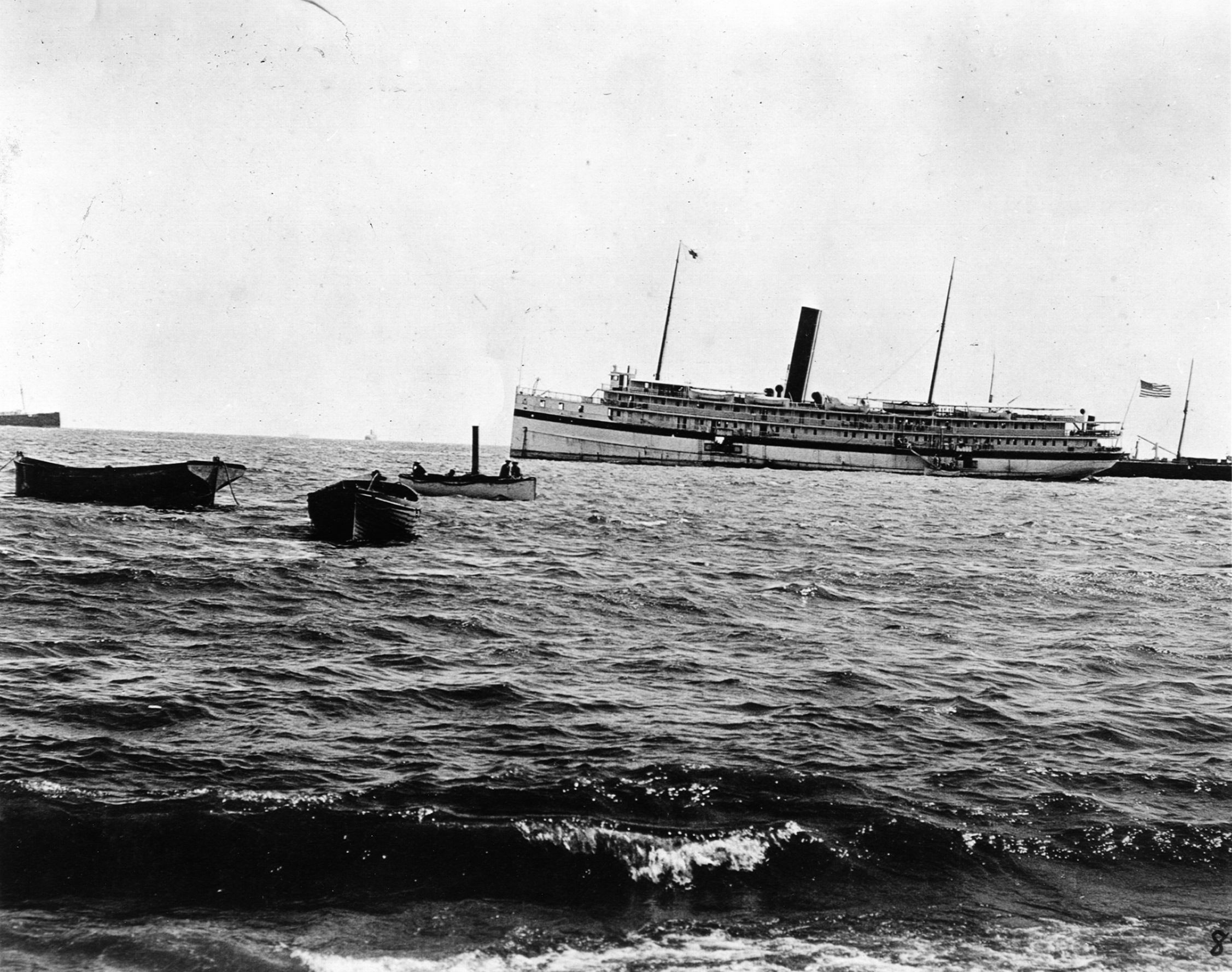

But the Army learned from its mistakes. Medical boards were convened for each problem that arose, from tainted meat to yellow fever. No diseases were ever found in canned meat—soldiers, it turned out, just enjoyed complaining about their rations. Women were included in the services to act as nurses. By the end of the war 1,563 women served as nurses.

After the war the Army continued to act on the lessons learned for the battlefield. West Point began teaching military hygiene in 1906. The causes of yellow fever were identified by Major Walter Reed and treated. Inoculations against typhoid fever became mandatory in the U.S. Army in 1911.

During the “Splendid Little War” of 1898 medicine had come a long way from the Civil War, but Army medicine still had a long way to go in keeping soldiers alive and healthy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments