By Leo G. Barron

Marvie is a quiet town nestled in the Ardennes region of southern Belgium. A farming village with a population of several hundred people, history has almost forgotten the town, but on one day in December 1944, Marvie lay astride a road that led to another town—Bastogne. If the German panzergrenadiers and tanks had overrun the glider infantrymen who defended Marvie, they might have taken Bastogne, and the history of the Battle of Bulge would have been radically different.

Unlike their airborne brethren, the glider infantry of the 101st Airborne Division has lived in the shadows of history. At Marvie, however, the 327th Glider Infantry showed its mettle and earned the moniker of the Bastogne Bulldogs.

Manteuffel’s Dilemma

On December 16, 1944, three German armies crashed through the thin American lines on the Western Front in the area known as the Ardennes Forest. The Germans’ objective was the city of Antwerp, Belgium, a great seaport then in use by the Allies for the supply of their armies fighting toward the German homeland.

The Fifth Panzer Army, under the command of General Hasso von Manteuffel, had the task of securing the southern flank of the German drive to Antwerp and seizing the city of Brussels. To accomplish this mission, it would have to penetrate the American lines along the Our River and seize several crossings at the Meuse River. More important, it had to control two towns, St. Vith and Bastogne.

Manteuffel had to make a difficult choice about Bastogne. The commander of the Fifth Panzer Army wanted Bastogne, but he was not willing to risk losing the Meuse River crossings to get it. During the preliminary operational planning, he ordered General Heinrich Luettwitz, commander of the XLVII Panzer Corps, to attempt to capture the vital town through a coup de main, using the Panzer Lehr Division, under the command of General Fritz Bayerlein. If that failed, the 26th Volksgrenadier Division would surround the town, allowing the other two panzer divisions in the corps (2nd Panzer and the Panzer Lehr) to continue their westward advance to the Meuse.

For Luettwitz the idea of leaving Bastogne in the rear, unconquered, meant greater problems later in the operation, and he strongly believed that he needed to concentrate his forces to capture the town before he could move the bulk of his corps to the west. As events unfolded, history would prove him right.

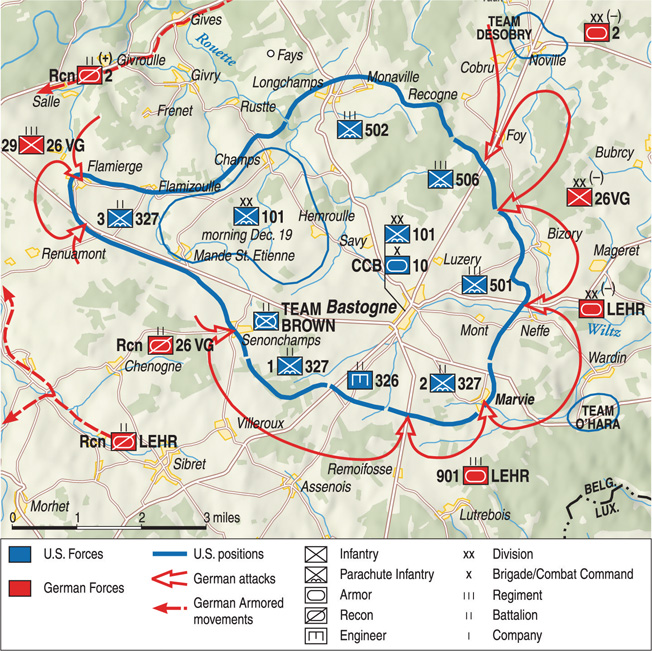

By December 21, 1944, the XLVII Panzer Corps had attempted several times to capture Bastogne, and each had failed. After a day of bitter fighting, the corps had surrounded Bastogne. Inside the town was the American 101st Airborne Division and Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division. It was clear that Luettwitz wanted to seize the town, knowing that the American paratroopers, so long as they had ammunition and food, would continue to resist his forces and disrupt his supply lines. Bastogne was also an important crossroads town, and control of it could facilitate the westward movement of German forces.

Marvie: Key to Bastogne

Yet, Manteuffel wanted the XLVII Panzer Corps to continue its advance toward the Meuse, northwest of Bastogne. As a result, Luettwitz could commit only one reinforced Volksgrenadier division, the 26th under General Heinz Kokott, to the capture of the vital road hub.

Luettwitz decided to gamble. He sent the besieged garrison a surrender ultimatum on the 22nd. The Americans called his bluff as General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne, replied famously, “Nuts!”

Luettwitz faced a dilemma. He had to respond with force. Luckily, the 26th Volksgrenadier Division was not toothless. Luettwitz had authorized the transfer of one battle group from Panzer Lehr to remain with the 26th Volksgrenadier Division south of Bastogne. This was not likely a popular decision with Fritz Bayerlein, the commander of the Panzer Lehr Division. He was losing one of his maneuver regiments, the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment, two panzer companies, and a battalion of artillery. With this force, coupled with the rest of the 26th Volksgrenadier Division, Luettwitz wanted Kokott to squeeze the noose around the neck of the American forces within the Bastogne perimeter and then penetrate it.

Kokott sensed that the best place to break though the American lines was near the southern side of the Bastogne perimeter. The 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment controlled the sector and reported that the American forces near Marvie were weak. In addition, both Kokott and Luettwitz sensed that the forces within Bastogne were not strong enough to continue their resistance if the Germans kept up the pressure. In preparation for a major attack on the night of the 23rd, Kokott and Luettwitz decided to increase the pressure around the entire Bastogne perimeter and close any potential gaps in their own encirclement of the American forces during the day.

Kokott’s 26th Reconnaissance Battalion would attack Mande St. Etienne in the west, while the 77th Volksgrenadier Regiment would attack Champs and advance to the south. Meanwhile, a battle group from the 2nd Panzer Division would strike Flamierge. This would close any gaps, tie down U.S. forces in areas away from the main target, and perhaps even draw American forces away from the southeast sector.

For the main attack, Kokott chose the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment and set the date for December 23. The 901st was relatively fresh and had not sustained serious losses in the prior few days. Next, Kokott decided to attack at dusk because the Americans controlled the skies during the day, and their fighter-bombers were very effective against tanks in the open. Moreover, by nightfall the other operations near Champs and Mande St. Etienne would be complete.

If the 901st penetrated the American defenses, Kokott could then order an all-out assault on Bastogne itself. To accomplish this, the 901st Panzergrenadier battle group had to breach the Bastogne defenses from the southeast and seize the town of Marvie in order to allow for a general attack on Bastogne. The time for its attack would be after 5 pm.

The U.S. Order of Battle

Opposing the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment was the U.S. 2nd Battalion, 327th Glider Infantry Regiment. The acting commander was Major R.B. Galbreaith, who was the executive officer of the battalion. The original battalion commander, Lt. Col. Roy L. Inman, had sustained injuries during an earlier attack on Marvie on December 20. The battalion held one of the most extensive sectors in the division. It extended from Marvie in the east to the Bastogne–Lutrebois Road in the west. On the eastern flank was the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, while on the western flank was the 326th Parachute Engineer Battalion.

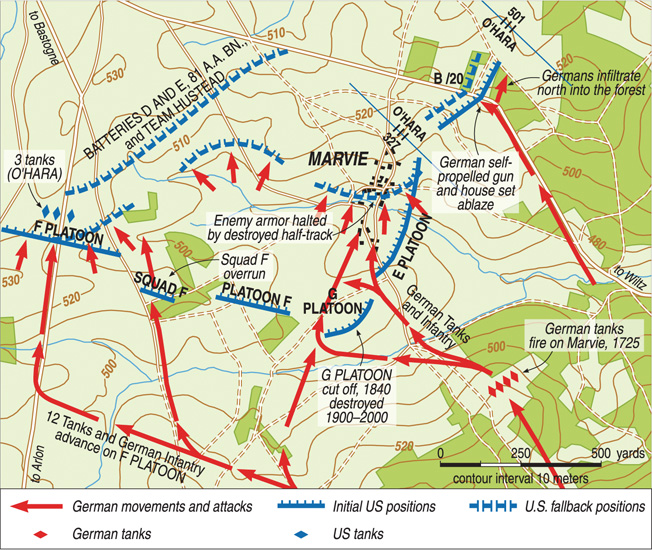

From west to east, Galbreaith arrayed his forces along the high ground that overlooked an east-west road that led to the town of Martelange to the west. His westernmost unit was a platoon from G Company. Farther to the east was F Company, which was situated between two G Company platoons. East of F Company was a G Company platoon that occupied the forward slope of Hill 500, the highest terrain in Galbreaith’s sector. After Hill 500, a road bisected the battalion area of operations and ran directly north into Marvie. To the east of the road was a platoon of engineers. In addition, along the easternmost flank, was E Company.

The entire frontage for the battalion was nearly two miles, almost double the area a battalion could doctrinally defend. Colonel Joseph Harper, Galbreaith’s boss and the commander of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, did not have much of an option. His regimental area of operations extended from Marvie in the east to Mande St. Etienne in the west, which was a distance of more than four miles. He had no choice but to stretch his forces thin to cover the entire southern approach to Bastogne.

The glider men were not the only soldiers in and around Marvie. Team O’Hara, from Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division, was also in the southeastern sector of the Bastogne defenses. Lt. Col. James O’Hara commanded a combined-arms task force of medium and light tanks, mechanized infantry, and engineers. The force was mainly north of the Bastogne-Wiltz highway on a reverse slope, located to the northeast of Marvie.

O’Hara’s total force comprised 19 officers and nearly 300 enlisted men, whom he divided among several armored infantry companies and attached tank platoons. More important, he owned six M4 Sherman medium tanks, a forward observer Sherman tank, one Sherman tank with a mounted 105mm howitzer, four M5A1 Stuart light tanks, and four 75mm howitzers mounted on M8 armored cars.

On the night of the 23rd, Team O’Hara had assembled a significant amount of firepower to block any German attempt to flank Marvie from the north. South of the road, O’Hara had positioned two light machine guns and one heavy machine gun. They covered a minefield and a roadblock. With them was one platoon of infantry from B Company, 54th Armored Infantry. To provide antitank defense, O’Hara buttressed the southern flank with three Shermans, including one with a 76mm gun that the forward observer used.

North of the road was another platoon from B Company. Like the southern platoon, O’Hara had supported it with two tanks; one had a 75mm gun, while the other was a 105mm howitzer mounted on a Sherman. Between the two platoons, O’Hara had placed a pair of outposts to overlook the roadblock, while in the building just to the south of the road was the B Company command post. On the far northern flank were two heavy machine guns, and their principal direction of fire was to the north. Behind the primary fighting positions were O’Hara’s headquarters and a heavy machine gun, which his engineers operated. Finally, far to the rear was his platoon of five light tanks, which were laagering at the main intersection where the east-west Wiltz Road crossed the north-south Marvie Road.

Setting Up the Attack

The terrain around Marvie favored the attackers. For observation and fields of fire, the Germans possessed the high ground to the south of Marvie, and with it they could observe most of the American perimeter in this sector. An extensive forest called the Te’re dol’Hesse ran along the southern length of the Remoifosse Road, which would screen the German forces assembling for an attack on Marvie. The same woods that provided concealment would also, however, be an obstacle for the German forces and would severely restrict much of their mechanized units. Therefore, the German tanks would have to use the roads and trails until they reached the open fields.

From Hill 500 the Americans could observe German movement within the wood line. If the Germans seized it, however, they could lay enfilade fire on the American forces in Marvie to the northeast. The most likely avenue of approach for German mechanized forces would be along the north-south road that bisected the Remoifosse Road and led directly into Marvie and on to Bastogne.

Colonel Paul von Hauser, who commanded the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment, planned his attack along several lines. The decisive operation would advance up the road that ran directly north into Marvie, while the main shaping operation would move up the highway that ran between Remoifosse and Bastogne. A second shaping operation would inch its way northward along the road that connected Wiltz and Bastogne to fix the American forces to the northeast of Marvie. If everything went according to plan, Kokott would then order his general assault once his forces had achieved a decisive penetration. The only variable was the glider men of the 327th. How would they react to Kokott’s plan? He would have his answer soon.

The Assault Begins

At approximately 5:15 pm, the German attack began. Tanks fired from a position in the forest hollow of Martaimont several hundred meters to the southeast of Marvie, while German machine guns opened up along the entire wood line. Their target was the men of 2nd Battalion. Their mission was to suppress the glider men in order to prevent them from responding with accurate fire against the German forces. Meanwhile, panzergrenadiers dressed in snowsuits edged their way forward from concealed positions in the wood line. Tracers crisscrossed the night sky.

Around 5:35, as the panzergrenadiers dashed and rolled from covered position to covered position, their first objective became clear to the glider men. It was the lone platoon from G Company at the base of Hill 500. The American platoon leader was Lieutenant Stanley Morrison. He had already been a POW briefly during the attack on Marvie on the 20th, but when that attack broke down the Germans left him behind in the town. For this attack, the Germans committed the 2nd and 6th Companies of the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment to seize the vital hill and then the town. In addition to the panzergrenadiers, four tanks accompanied the infantry to provide suppression fire, while a platoon of 120mm mortars and a platoon of 75mm guns provided indirect artillery fire to secure the flanks of the attack.

The Americans immediately responded with two batteries of 75mm howitzers from the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, firing from the town of Hemroulle. Their target was the area just south of Hill 500, and by 6 pm, B and D Batteries had saturated the area with over 75 rounds of high explosives.

The other shaping operations now began in earnest. At 6 pm, 12 more tanks with accompanying infantry struck F Company near the Remoifosse-Bastogne Road. Some of the panzergrenadiers quickly overwhelmed and destroyed a squad from F Company defending a copse of trees north of the road to Remoifosse. While some of the Americans escaped, the Germans killed or captured most of the squad. In response, the B and D Batteries from the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery shifted their fire toward the intersection due south of Remoifosse. The 463rd called for additional assistance from the 377th Parachute Field Artillery, and this battalion began to fire on the same area.

Because of this massive artillery concentration and his dogged resistance, Lieutenant Leslie Smith’s platoon, which overlooked the Remoifosse–Bastogne Road, temporarily blocked the German tanks. Smith’s heaviest weapons were bazookas. The fighting was fierce. German tanks fired 15 rounds into Smith’s command post, which subsequently caught fire. Smith refused to leave the burning building and decided to continue the fight from the basement. At one point, two German tanks closed within 50 yards of Smith’s lines but were turned back. During the night, Smith’s men repelled three separate attacks.

“We’re Still Holding On”

Elsewhere, however, the American main line of resistance was beginning to buckle. Despite the massive steel storm, the German panzergrenadiers inched forward, and by 6:40 they had reached the base of Hill 500. Once there, they infiltrated the houses that surrounded the base of the hill and slowly began to envelop Morrison’s platoon.

Sensing the threat, Morrison ordered some of his men on the flanks to fall back to prevent the enemy from turning him, but the Germans had fixed his platoon. Soon they would cut him off from the rest of the battalion. Believing they had neutralized the threat, some of German tanks then turned their attention toward the town of Marvie and began to hurl rounds into the village while two Mark IV tanks began to advance toward the town.

Morrison had very little to stop the clanking metal monsters. The only significant antitank weapon available was a 57mm gun mounted in a half-track. Colonel Harper had placed the gun at the base of Hill 500 to prevent German tanks from using the road that led into Marvie and then to Bastogne. Originally, a 37mm gun had been placed there, but Harper wanted something with more punch. He asked O’Hara for a tank, but O’Hara declined and offered the 57mm instead.

The gunners had just started to set up the 57mm weapon when the attack started. The driver, seeing two German tanks emerge from the wood line to the south, reversed the vehicle and started to head back toward Marvie. The men of E Company saw the approaching half-track with the two German panzers and panzergrenadiers behind it, and opened fire on the hapless half-track crew, slaughtering them. Their smoldering vehicle rolled to a stop at the southern end of Marvie near a church, blocking one of the main avenues of approach into the town.

The two German tank commanders, probably thankful that the Americans had shot up their own vehicle, quickly advanced into the southern half of Marvie after crossing the Rau de Wez Creek, but when they reached the wrecked half-track they realized they could not get around it. Therefore, they reversed their panzers and headed back to the south.

Despite the German tanks withdrawing temporarily, the end was near for Lieutenant Morrison. Panzergrenadiers were sweeping past his hill and advancing on Marvie, while some began their final assault on Hill 500 itself. Colonel Harper, worried about his platoon leader, called the lieutenant directly over the radio. “What is your situation?” the regimental commander asked.

Morrison replied that the panzergrenadiers’ snowsuits provided them great concealment and made them difficult targets. Thus, the Germans were closing in on his positions almost unmolested.

“How are you now?” Harper then inquired.

The answer was ominous. “Now they are all around me. I see tanks just outside my window. We are continuing to fight them back, but it looks like they have us,” Morrison reported. His voice never faltered, and instead of panic, Harper heard only courage.

Harper waited three minutes and called Morrison back to get another update. Morrison answered, “We’re still holding on.” Then the line was cut.

Ambush on the Wiltz-Bastogne Road

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas J. Rouzee, the regimental executive officer, then looked over at Harper and remarked, “I guess that’s the end of Morrison.” It was. Morrison and his platoon, together with some of the nearby engineers from C Company, 326th Engineers, were gone. Time was running out. Harper needed tanks to plug the hole left by the loss of Morrison’s platoon, and he knew of one man who could provide those tanks.

Unfortunately for Harper, O’Hara had his own problems. He warned a frustrated Colonel Harper, “They are attacking me also and trying to come around my north flank.”

For O’Hara, the fighting had started at 6:01 pm, when two enemy heavy machine guns opened up near his positions. They were laying suppressive fire on the town, and the 54th Armored Infantry units quickly neutralized the guns with flanking fire. Despite this small success, General Kokott and Colonel Hauser’s plan was beginning to work. They initially had fixed the two flanking forces in the American lines, which meant they now could penetrate Marvie without worrying about their own flanks.

Their success did not last long. Matters started to unravel quickly on the eastern flank of the German attack along the Wiltz-Bastogne Road. A force of tanks and self-propelled guns slammed into Team O’Hara northeast of Marvie at 6:45. The lead German vehicle was a 75mm self-propelled assault gun. Behind it were Mark IV tanks with infantry trailing. The American soldiers manning the outpost on the road wisely allowed the armored vehicles to pass through the checkpoint without firing a shot. Then, as the German assault gun made the final turn around a bend in the road, a Sherman had a point-blank flank shot on the vehicle.

The Sherman rocked back as its 75mm gun bellowed. At the speed of sound, the armor-piercing shell hurtled through the air and pierced the thin armor on the side of the self-propelled gun. The wounded metal beast then exploded, showering the air with sparks. Simultaneously, the men in the outpost opened up with their machine guns, spraying the accompanying panzergrenadiers with hot lead. The night sky erupted as German tanks and machine guns replied, searching in vain for the killers.

The rounds inside the destroyed German vehicle began to cook off, causing it to burn furiously, and this light provided visibility for the German attackers. Thinking that the Americans had used a nearby farm as an ambush position, the panzergrenadiers concentrated their fire at the loft, which caused the hay inside the barn to catch fire. Soon, light from the engulfed barn and the burning gun bathed the roadblock in light, depriving the U.S. infantry and tanks of their prized concealment. The American vehicles withdrew to their alternative fighting positions a hundred yards to the west. Like the tankers, the soldiers in the outposts also fell back, but before they left they destroyed an approaching German half-track.

Assault on the Road Repelled

Meanwhile, the panzergrenadiers infiltrated the woods to flank the American lines to the north. Most of the American guns remained silent, but one machine gunner did return fire on the northern flank, and the Germans thanked him with hand grenades. They killed the gunner and wounded his assistant gunner. Now exposed, most of the men in that trench line withdrew to the rear. With his northern flank falling back, O’Hara then called his commander, Colonel William L. Roberts, and told him that the Germans were trying to envelop his forces. Not wanting to alarm his boss too much, O’Hara next added that he thought he could still hold back the Germans. The time was 7:36 pm.

Not all of the Americans could escape by falling back. One man remained in his foxhole as the panzergrenadiers swarmed around him. As one group approached, the quick-thinking soldier slumped over, hoping that the Germans would think he was a corpse. When they reached the lip of the foxhole, the panzergrenadiers jumped in and kicked him, thinking he was dead. Then they pilfered his pockets for souvenirs while another panzergrenadier confiscated his Browning automatic rifle. After they left, the soldier could hear the Germans dragging a towed 50mm Pak 38 antitank gun into the wood line.

Once set up, it started to fire down the road. Using it as bait, the Germans tried to draw the fire of American tanks while a German tank waited for the American tanks to reveal themselves. Unfortunately for the Germans, they did not take into account American infantrymen, who hurled several hand grenades at the gun and silenced it.

At 8 pm, the American infantrymen heard the clanking of metal treads as another German Mark IV rolled to a stop and began to fire from north of the Bastogne-Wiltz Road. Like a dazed boxer, the lead Mark IV then shot five rounds from its 75mm gun, hoping desperately to hit something as it tried to find the American tanks by observing the muzzle flashes of their guns. The chaos and din had overwhelmed the senses of the German crew. They hit only air.

Their adversaries had better luck, however. The Sherman with the 105mm howitzer and the Sherman with the 76mm gun then attempted to deliver a deathblow as they both slammed rounds into the doomed Mark IV in a deadly cross fire. The rounds from the 105mm howitzer bounced off the panzer like worthless water balloons since its gun was firing only high-explosive ammunition, but one armor-piercing round from the 76mm gun proved lethal.

Suddenly, without the support of their armored vehicles, it seemed the panzergrenadiers were facing defeat along the Bastogne–Wiltz Road. As the panzergrenadiers passed the burning buildings, they were silhouetted, and their snowsuits proved worthless in this illuminated position. As if on cue, the American machine gunners and riflemen unleashed a storm on the now-exposed Germans. Bodies crumpled as a tempest of lead peppered the hapless men and shattered their nerves. Their attack broken, the Germans began to fall back to their lines, but the Americans did not allow a respite. Forward observers began to call for fire, and artillery and mortars responded, plastering the retreating panzergrenadiers. What had begun as a promising advance had ended in a bloody repulse.

“I Must Have Tanks”

While the Americans handily had thrown back the Germans northeast of Marvie, the men in E Company and the remnants of G Company engaged in a bitter struggle inside the village. Sometime after the fall of Hill 500, the panzergrenadiers and tanks returned to Marvie. At 8 pm, Major Galbreaith rang up Colonel Harper and informed him of the deteriorating situation within Marvie. German tanks were approaching the town and panzergrenadiers had seized several homes on the south end of town.

More important, these panzergrenadiers were working their way northward toward Galbreaith and his command post. Galbreaith estimated that at least two squads, using the tanks to cover their movement, had penetrated the town. Without tanks of his own, Galbreaith knew he had no real way to overcome the firepower deficit, which meant those two squads would grow into platoons and then into companies. If the Germans occupied the town with a company, Marvie was lost. If the Germans captured Marvie, Bastogne would follow.

Galbreaith needed reinforcements now. “Can’t I get tanks?” the acting commander of 2nd Battalion asked his regimental commander. Harper replied, “I’ll try.” The colonel then tried to raise O’Hara over the landline. The connection was dead. Harper next attempted to use the radio, but O’Hara’s connection was too weak. The situation in Marvie could not wait for the signal officers to repair the communications network. Galbreaith warned Harper, “They are all around us now and I must have tanks.”

Undeterred, Harper ordered the major, “You call O’Hara on your radio and say ‘It is the Commanding General’s orders that two Sherman tanks move into Marvie at once and take up a defensive position.’” For Harper, it was better to ask for forgiveness later than to ask for permission when time was critical. He did not want a repeat of Hill 500 in Marvie. To lose a platoon was a tragedy, but to lose a whole battalion would be a disaster.

By now, Harper had committed all his reserves, and he requested forces from the division headquarters. He also decided to thin some of his forces in other sectors so that he could shift reinforcements to plug the hole at Marvie. First Lieutenant Charles J. Roden, who commanded two platoons from B Company, 326th Engineers, received the order around 8 pm to pull them out of the line and lead them to Marvie. Roden then told his engineers to prepare to move out.

One of Roden’s engineer platoon leaders, Lieutenant Robert Coughlin of 3rd Platoon, B Company, then pushed on ahead of his platoon to find a suitable place to set up his battle position, and he brought with him all the squad leaders. By now, several buildings in Marvie were on fire, providing some illumination as Coughlin mapped out his platoon’s positions. While trudging through the snow in Marvie, Coughlin noticed that a small stream wound its way through the center of town along an east-west axis, and, more important, he determined that the banks were too steep for tanks to cross. Therefore, he decided to position his platoon behind the stream.

Refortifying

Luckily, the glider men had dug some foxholes earlier, which provided Coughlin’s platoon excellent fighting positions. Using the roads and a fence that lined the north bank of the stream as fire control measures and boundaries, Coughlin arrayed his squads from west to east: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Squad. He reinforced the 1st and 2nd Squads with two machine guns each, and he placed his three bazooka crews in positions where they could cover the culverts that crossed the stream. Within a few minutes, his platoon was ready for the next German assault. By 8:30, Coughlin’s commander, Lieutenant Roden, slipped the rest of B Company into Marvie after the second wave of German forces had stalled at the southern edge of the town.

Meanwhile, O’Hara responded to Galbreaith’s pleas with a section of two Sherman tanks from C Company, 21st Tank Battalion. One of the tank commanders, Staff Sergeant Stan Davis, had just swept aside a German attack north of the town, and he believed his tank had destroyed a self-propelled assault gun during the chaotic melee. Despite this success, Davis did not relish the idea of driving tanks through a town at night, especially one that he hardly knew. What he did know was Marvie had two main north-south roads that lined the town, and inside the town Marvie had three east-west roads that connected the two parallel roads. These roads then merged on the south end of town. Now, his task force commander was ordering him to push into the unknown, but he sensed the situation in Marvie was dire. His men mounted their tanks.

Within a few minutes, the American tanks arrived at the north end of Marvie. The battalion intelligence officer, First Lieutenant Thomas J. Niland, linked up with the tanks where the road forked north of the town. Niland warned Davis and the other tank commander that he believed the Germans had moved three tanks with infantry into the south end of Marvie near the church. Niland also cautioned them that the glider men occupied the basements and the ground floors of several homes in Marvie.

Finally, he told them about the knocked-out American half-track blocking the eastern route in Marvie. Davis and the other tank commander then decided to cover both roads by splitting their section. Davis chose the eastern road and drove his tank down to a position where he could see the crossroads where he believed the glider men had established their battle positions. He could see the burned-out half-track to his front. Satisfied with his field of fire, he next backed his tank into a courtyard so the buildings would provide concealment for his rear and his western flank.

His guiding done, Niland then returned to his fighting position. His men normally did not man foxholes during combat actions, but the German attack had destroyed two platoons and had severely mauled another company. Galbreaith needed everyone who could shoot a rifle in the foxholes fighting, and that included supply clerks, intelligence personnel, and headquarters staff. Therefore, Niland’s intelligence section now was a provisional rifle section, defending the battalion command post. Niland was confident that his men were up to the task, and he knew they would fight like battle-tested infantrymen.

In addition to his internal reserves, Harper received 40 men from A Company, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, under the command of Captain Stanley Statch. At 9:45 that night, Harper placed these paratroopers north of Marvie, along the road that led into Bastogne. In addition to the paratroopers, Harper received D and E Batteries from the 81st Antiaircraft Battalion. These batteries provided him with 12 .50-caliber machine guns, and Harper arranged in them in an arc to the north of Marvie. The machine guns were in position by 10:30.

To bolster his western flank, Harper ordered his executive officer, Colonel Rouzee, to assume command. Rouzee then gathered 24 men from F Company and, together with the paratroopers from the 501st, he established a battle position near Smith’s platoon. Rouzee wanted to recapture Hill 500, but when he saw the terrain, he realized he would have to remain on the defensive. In addition, Captain James Adams, the F Company commander, rounded up stragglers who had escaped the second German attack and re-established his positions.

The Final Attack

While Harper shuffled his lines, the Germans prepared for one final lunge. The first two attacks bent the American lines, but they had not broken them. Moreover, although the Germans were inside Marvie, they did not control it. Their eastern flank attack had ended in failure. To the west, after they had advanced past Hill 500, they had not seized any other key terrain, and the paratroopers still held the high ground north of Remoifosse. Hauser decided to send in his reserves. The third attack likely would decide the fate of the small town of Marvie.

Around midnight, the third and final German push began in Marvie. The panzergrenadiers, using the concealment of night, crept along the roads northward to the American lines, while their tanks inched their way forward. Their commanders dampened the noisy diesel engines by not revving the throttles. Despite their strenuous efforts, the glider men and engineers could hear the low rumble, like the incessant thunder from a distant storm. They girded themselves since most of them could do little harm to a tank with only their rifles.

Davis, a Sherman tank commander, also heard the panzers approaching. He stared into the night but could see only the outline of the destroyed half-track. He then directed his gunner to aim the 75mm gun to the right of the halftrack, since that was the only spot where a tank might try to drive around the twisted hulk. While the gunner was looking through the scope to adjust his aim, Davis told the loader to load an armor-piercing round into the breech and to ready the ammunition racks with an ample supply of armor-piercing and high-explosive rounds. While his men prepared the Sherman for battle, Davis detected the sound of engines revving. He surmised that one German tank was trying to push the half-track off the road.

For 15 minutes, the glider men, engineers, and tankers heard the shuffling of boots and the clanking of treads as the Germans readied themselves for their assault. Then a single flare shot up into the clear, night sky, illuminating the snow-covered earth below. Like a starting gun, the flare became the signal for hundreds of soldiers on both sides. The night erupted once again as the panzergrenadiers and glider men blazed away at each other.

Across from the engineers of B Company, three German tanks rumbled forward with panzergrenadiers following closely behind them. In response, 3rd Platoon’s machine guns opened up on the panzergrenadiers, and within seconds bodies began to fall in the snow. The cries of the wounded panzergrenadiers quickly added to the cacophony of chaos.

Forward observers working for the glider men began to identify targets for the guns in the rear. Within minutes, the sounds of flying freight trains overhead greeted the ears of the harried glider men as round after round of high-explosive shells rained down on the advancing Germans to the south of Marvie. The 463rd Parachute Field Artillery’s 75mm howitzers plastered German infantry southwest of Marvie, and within minutes the 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion added their barrels to the hurricane of steel that crashed upon the German forces.

While fighting broke out to the west, Davis decided to attack. His Sherman tank rocked backward as a 75mm armor-piercing round shot out of the muzzle of its gun. The unseen German tank retaliated, but its rounds were high as they careened into the buildings that surrounded the Sherman, setting them on fire. Within seconds, Davis’s crew loaded and fired several more armor-piercing and high-explosive rounds at the Germans. Afterward, Davis only heard silence from the Germans. He peered into the night and watched men bailing out of the tank. Davis exhorted his tankers to unleash the tank’s machine guns, while the gunner continued to fire high-explosive shells at the scurrying German crewmen.

For the engineers on the west side of Marvie, their six machine guns seemed to attract the attention of the other three tanks in the town. Two of the German tanks identified two of the machine-gun positions and retaliated. The shells shattered the trees above the machine-gun positions, showering the area with shards of wood and steel. Realizing that the Germans had a bead on their position, one machine-gun crew ceased firing.

Another one, however, continued to engage the panzergrenadiers. Staff Sergeant Mariano Ferra, the platoon sergeant for 3rd Platoon, knew the gunners would not hear his pleas, so he sent a runner to tell the other gunner to cease firing. The runner, however, did not reach them in time as another round exploded nearby, killing him instantly while he tried to crawl to the position.

At this point, the indiscriminate tracers had ignited a fire in the command post of G Company. The glider men, realizing that the command post was lost to the flames, had to fight their way out. The battalion intelligence section, fighting furiously to protect the command post, then destroyed a German machine-gun team that had crept into the town.

The two regimental 37mm antitank gun teams under the command of Lieutenant Neal Fahey were not as lucky. Artillery and mortar fire killed or wounded most of them. As the panzergrenadiers moved closer into town, the 2nd Battalion heavy weapons platoon had to move its command post. To cover their withdrawal, Private First Class Harry Bliss remained behind at his machine gun, shooting all of the attacking Germans, save one, whom he killed with a hand grenade.

Meanwhile, another German tank attempted to push north into Marvie along the center road, which was near the 2nd Squad, 3rd Platoon, B Company Engineers. A bazooka team overlooked the center road from a nearby barn window, and when another flare shot off, it revealed the enemy tank approaching the culvert. One U.S. soldier shoved a rocket into the back of the tube and frantically attached the wires, while the other aimed the weapon through the window. The tank rolled onto the culvert, and the American soldier squeezed the trigger. With a great whooshing sound, the rocket shot out. It sailed through the air and struck the German tank in its front sprocket. The machine lurched as it halted.

“Minen, minen, minen!” the panzer commander yelled out, as he lifted up his hatch.

Though the guns remained in working order, the bazooka team had immobilized the German tank. Instead of escaping, the German crew decided to use its ammunition on the town. With reckless disregard for civilian property, the Germans unleashed their main gun and machine guns on the buildings in town, setting fires and smashing walls. When they had used up their ammunition, the crew dismounted and escaped to the south.

Farther east, Davis and his tank heard more clanking noises as another tank approached his position. Davis’s roadblock now included a wrecked panzer and the burned-out half-track. As the German tank edged forward, Davis directed his gunner to aim above the hulk of the first enemy tank. When he felt it was close enough, Davis ordered his gunner to fire. The 75mm gun recoiled like a kicking mule. Not satisfied with the results, Davis ordered the gunner to fire another round. Following this volley, Davis could hear the German starting to reverse. After several minutes, the tank retreated, and Davis heard a third German tank follow it to the south.

The German Withdrawal

Without armored support, the German attack stalled, and no fourth attack would follow. By 3:30 am, the firing petered out as both sides paused to regroup. The glider men had fixed the 2nd Company of the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment inside the town, and its commander, Lieutenant Furstenau, lay dead on the battlefield. Hearing the bad news, Kokott decided to call off the attack. He did not want to commit his division reserves into the Marvie maelstrom. He determined that the window of opportunity had closed at Marvie. He had to husband his forces for a much larger attack that was to take place in the western sector on December 25.

The men of the 327th Glider Infantry, together with the engineers of the 326th and the tankers of Team O’Hara, had stopped the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment. Though the Germans would try to penetrate the American defenses of Bastogne on Christmas Day, they would not try to do it again at Marvie.

Good article. I once worked with a gentleman who was there with the 327th. I don’t know if he was in the 2/327th, but he was in the thick of it. I sat next to him for about a year at the engineering firm we worked at and he was more than willing to talk of his time at Bastogne.

2 minor comments offered as clarification: 1st, there were no 75mm guns mounted on M-8 armored cars (Greyhounds). There were 75mm’s mounted on the M-8 HMC (howitzer motor carriage) which was based on the M-5 Stuart. And 2nd, the German tanks were not diesel fueled, they had gasoline fueled Maybach engines.