By Blaine Taylor

On July 19, 1940, fresh from his victorious campaigns on the Western Front, German Führer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler delivered his “peace speech” to the Reichstag in Berlin’s Kroll Opera House. Among those present was American Columbia Broadcasting System radio journalist William L. Shirer.

Fascist Entertainment, Italian-Style

In his memoir, Berlin Diary, Shirer recalled, “Count [Galeazzo] Ciano, who was rushed up from Rome to put the seal of Axis authority on Hitler’s ‘offer’ of peace to Britain, was the clown of the evening. In his gray and black Fascist militia uniform, he sat in the first row of the diplomatic box, and jumped up constantly like a jack-in-the-box every time Hitler paused for breath, to give the Fascist salute.

“He had a text of the speech in his hand, but it was probably in Italian, so that he was not following Hitler’s words. Without the slightest pretext, he would hop to his heels and expand in a salute. Could not help noticing how high-strung Ciano is. He kept working his jaws, and he was not chewing gum.”

Immediately after the end of the war, Ciano became one of the first of the late Axis Pact leaders to have his wartime memoirs published, in the form of The Ciano Diaries, 1939-43, followed by a second volume in 1953, Ciano’s Hidden Diaries, 1937-38. The existence of the diaries was first publicly mentioned in American diplomat Sumner Welles’ book, The Time for Decision, when he recorded a February 26, 1940, conversation with the Italian Foreign Minister and son-in-law of Il Duce of Italy, Benito Mussolini: he “took out of a safe his famous red Diary in which he recorded in his own handwriting his daily activities.”

A Diary Provides An Inside View Of The Axis

In his introduction to the first published volume of Ciano’s diaries, Welles would later add, “I believe it to be one of the most valuable historical documents of our times … an opportunity to gain a clearer insight into the manner of being of Hitler’s Germany and of Mussolini’s Italy … during the years when almost the entire world trembled before the Axis partners. They will find in the Diary a hitherto unrevealed picture of Germany’s machinations during those fateful years.

“They will see perhaps more vividly than before how stereotyped was Hitler’s course in utilizing his most solemn pledges to other governments, and by no means least to his ally, Italy, as a means of deluding them as to his real intentions.”

For many years thereafter, there were armloads of books by and about Mussolini available in the popular arena. Most recently, English historian Denis Mack Smith’s Mussolini and Mussolini Memoirs have been reissued, as have the postwar accounts of both the widow of Il Duce and his daughter, Mussolini: An Intimate Biography by Rachele Mussolini and My Truth by Edda Mussolini Ciano.

“Mussolini’s Shadow” Get His Due

Indeed, the overall subject of Italy at war has also been covered in a stunning trilogy of works by the English historian MacGregor Knox: Mussolini Unleashed: 1939-41/Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy’s Last War; Common Destiny: Dictatorship, Foreign Policy and War in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany; and Hitler’s Italian Allies: Royal Armed Forces, Fascist Regime, and the War of 1940-43.

Strangely, following the publication of the Ciano diaries within the first eight years after the war’s end, there remained no biography in English of Ciano himself, for many years perhaps the number two man in the Fascist regime with the possible exception of Air Marshal Italo Balbo. This was rectified at last in 1999 with the publication of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ray Moseley’s superb biography, Mussolini’s Shadow: The Double Life of Count Galeazzo Ciano, which unveiled the man in all his complexities.

A Family Capitalized On The Fascist Movement

Ciano was born at Leghorn on March 18, 1903, as Count di Cortelazzo, a hereditary title that belonged to his eminent father, Captain Costanzo Ciano, who had served with gallantry and distinction in the Italian Royal Navy during World War I.

Noted Sumner Welles, “The elder Ciano was one of those most responsible for the initial success of the Fascist movement. Promoted to the rank of Admiral and ennobled immediately after Mussolini rose to power, he subsequently served for many years as Minister of Communications and as President of the so-called Fascist Chamber of Deputies. Today he is best remembered for the immense fortune which he accumulated through the opportunities offered him by his controlling influence within the Fascist Party and, in particular, during the years when he held office as Minister of Communications.”

This path to riches would later be followed by the younger Ciano, when he saw his financial opportunities arise after he married Edda Mussolini. He graduated from the school of law at the University of Rome in 1925. He had a college job as a Roman daily newspaper drama and arts critic, which would avail him greatly in his later career, just as it had Il Duce before him. Initially, he was critical of Fascism despite his father’s position within the regime, or maybe because of it, although he greatly revered the Admiral.

Marrying Into the Family

Upon graduation, young Galeazzo joined the Italian Diplomatic Service and by 1930 had served at posts in Rio de Janiero, Buenos Aires, Peking, and Vatican City. By then, Il Duce was firmly ensconced in power as the strongest premier Italy ever had (a record that still stands in terms of number of continuous years served in office). Ciano had also begun a passionate romance with Mussolini’s fiery first-born daughter, Edda. They were married at the Church of San Giuseppe in Rome on April 24, 1930. By 1938, their family would include daughter Raimonda and sons Fabrizio and Marzio.

Noted Welles, “Simultaneously, he became an ardent Fascist,” and his personal connection automatically guaranteed that the rest of a brilliant career was assured—or so one would have thought. After a stint as Italian Consul General at Shanghai, Ciano was promoted as Minister to China. In June 1933, he was a member of the Italian delegation to the London Economic Conference, following which he was named Il Duce’s personal press chief. Two years later, Ciano was promoted to Undersecretary of State for Press and Propaganda and became a member of the Fascist Grand Council, the party’s ruling body. He reached the apex of his career and the very apogee of his personal glory when, at age 33, he was named Italian Foreign Minister in 1936.

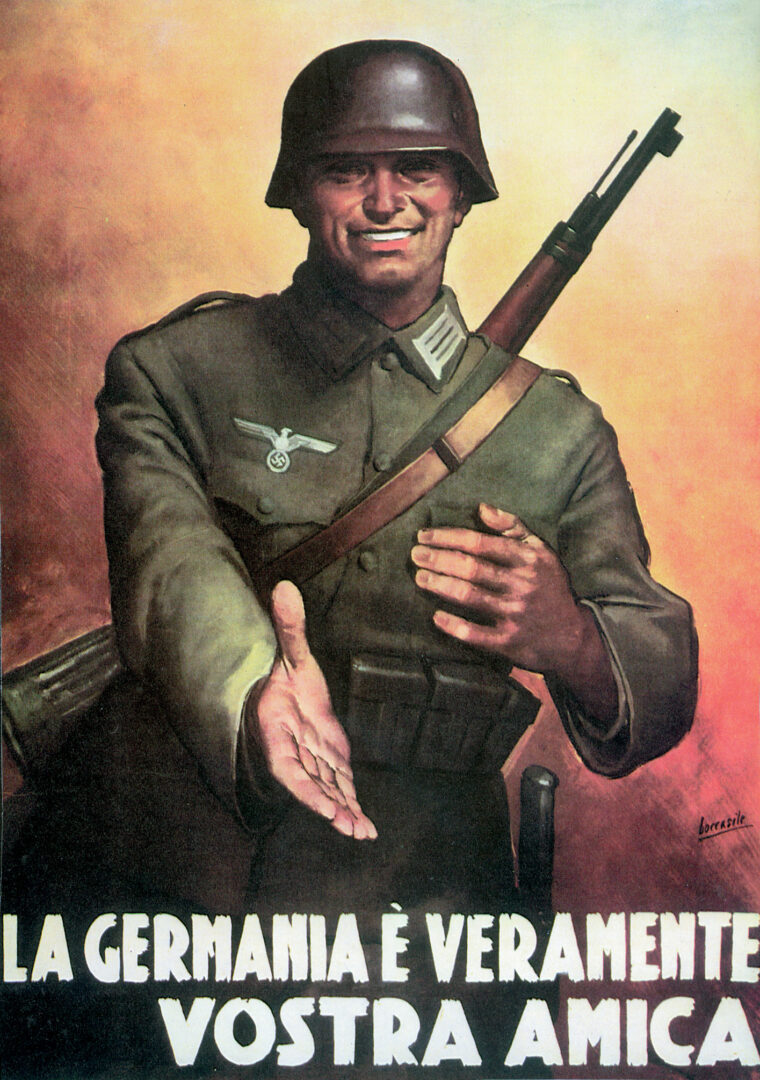

The Love-Hate Relationship With Nazi Germany

The duality of the nature of both Ciano’s and Mussolini’s relations with Nazi Germany has been told many times. The basic nub of this duality lay in a virtually unsolvable dilemma. Both men simultaneously admired and despised the Germans, as well as feared them.

They respected and coveted the raw, naked military power that the Third Reich represented to them, but at the same time, like the smaller states of Central Europe, feared that this colossus would someday engulf them, Fascism, and Italy herself. Had France and Great Britain agreed to squash Nazi Germany in 1934 and guarantee Fascist Italy her overseas empire in Africa in 1935, both men would gladly have joined in a Western anti-Nazi alliance. Coincidentally, this is also what their mortal enemy, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, was urging the West to do, but also to no avail.

Since Mussolini had Hitler on his doorstep at the Brenner Pass in Northern Italy and the Allies would not stop him, Il Duce decided to forge an alliance with Nazi Germany. Reluctantly, Ciano followed Il Duce’s lead, alternating between enthusiasm and private hostility toward the very idea that they were publicly promoting.

Ciano Recognized A Threat From An Ally…

This took the form of several treaties, the most important being the Pact of Steel of May 22, 1939, and the Tripartite Pact (which added Imperial Japan to the roster) of September 27, 1940. Both of these treaties committed Italy to a military entanglement against England, and later, the United States.

Noted Moseley, “Ciano played a central role in the Axis partnership negotiations with Hitler and [German Foreign Minister Joachim] von Ribbentrop and masterminded Italy’s invasions of Albania and Greece.”

Yet, according to Welles, as a seer Ciano was far more accurate than Il Duce: “He showed himself far superior … in his ability to see where Italy’s real security lay. He appears to have had no illusions from the time of the German occupation of Austria as to the danger inherent to Italy in German ambitions and in the extension of Hitler’s sway.

“Time and again in his diary he emphasizes his belief in the accuracy of the reports which come to him of the indications given by members of the Nazi hierarchy of Germany’s ultimate intention to seize Trieste and to occupy Italy’s Northern plains.

“The Diary proves that, as a statesman, Ciano saw the major issue accurately. He was under no illusions as to what a German-dominated Europe would imply for Italy. He was convinced that only through the defeat of Germany could any world order be established in which a sovereign Italy could survive.”

The Germans Had Ciano In Their Sights

All of these views Ciano daily recorded in his diary, as the Germans were well aware. Even before he voted against his father-in-law in the Grand Council session of July 24-25, 1943, which helped King Vittorio Emmanuele III remove Il Duce from office the next day, they knew full well that he was hostile to Nazi Germany. Dr. Josef Goebbels called him “a poisonous mushroom,” and all the Nazi leaders wanted him tried and executed for treason against Mussolini.

Despite this, following the overthrow of the Fascist regime, the Count himself feared the revenge of the Party far more than he did those of his former German allies and fled to Germany for safety, leaving his diaries behind in Rome. A reconciliation was attempted with the rescued Mussolini in Munich, but Rachele, Il Duce’s wife, was totally against it. Eventually, Ciano was sent back to Northern Italy to stand trial for treason under the auspices of the newly established Italian Fascist Salo Republic at Verona.

It was a foregone conclusion that he and the other accused would be convicted and executed. It was even feared that, were they somehow acquitted or not given death sentences, they might be shot in the courtroom by enraged Fascist radicals who had long hated the flashy, suave, high-living, womanizing count.

Mussolini Washes His Hands Of the Matter

It was here that his wife Edda entered the drama, pleading directly with both her father and Hitler for clemency. Il Duce ducked the issue by asserting that the matter was an internal one for the Fascist Republican Party to decide, while everyone knew that he could merely pick up a telephone and his wishes would be obeyed. As for Hitler, he told the distraught Edda that it was strictly a family matter to him and that he would not intervene. Ciano himself stated from his jail cell that he was proud of how loyal and stalwart a wife Edda was proving to be.

It was here that she attempted to play her trump card against both Nazi and Fascist dictators. That card was a threat to smuggle the diaries to the West and publish them in full, in all their embarrassing details, to a world hungrily awaiting back-biting gossip from the camp of the warring Axis partners. This they took seriously.

The Diary Provides an Ace In the Hole

Now entered the German SS. On December 28, 1943, a friend of the Count’s contacted SS Brigadeführer (Brigadier General) Wilhelm Harster, the Verona commander of the SS and SD (Security Service), and stated that if her husband were executed, Countess Edda would send the hidden diaries to the United States for publication. It was then suggested that a top-secret SS rescue plan be concocted to save Ciano from Fascist execution and deliver him and his entire family across the border to safety in Switzerland. In exchange, the diaries would be turned over to an eager Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler through the good offices of the head of the SD, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who backed the plan.

Thus was born covert Operation Conte which, had it been successful, would have at least spared Il Duce his eldest daughter’s grief. On January 2, 1944, final arrangements were made for Ciano to reveal the hiding place of the papers and the SD to kidnap him from his Verona jail cell. On the 5th, Harster received the diplomatic papers, but not the diaries. These Edda intended to hold back until her husband’s release, which was scheduled secretly for the 7th, the day before the trial was to start.

According to Peter R. Black in his book, Ernst Kaltenbrunner: Ideological Soldier of the Third Reich, “At the last moment, Himmler and Kaltenbrunner lost their nerve and sought Hitler’s approval for ‘Conte.’ The dictator flew into a rage at this contemplated disobedience and threatened the severest punishment if ‘Conte’ were attempted.”

Ciano Speaks From the Grave

Thus, on January 8, 1944, Edda Ciano Mussolini, after a harrowing journey, crossed the Swiss border carrying her husband’s wartime journals. On the 11th, the Count was shot in the back while sitting on a chair in front of a fortress wall in Verona. Unlike the other condemned men, he turned around at the last moment to face his executioners, a Fascist firing squad. His father-in-law and his mistress would follow him 18 months later, shot without a trial by Communist partisans and hung by their heels in a Milan gas station.

By the time the diaries were actually published, the war was over and Hitler, too, was dead. The Chicago Daily News published them over a 30-day period starting in June 1945. Il Duce’s widow, Rachele, died in 1980, followed by Edda 15 years later, at age 85, on April 9, 1995, almost four decades after the exciting events that made her and the diaries world-renowned. To the old Fascists she was the “Eccellenza,” an honorary title reserved for government ministers, ambassadors, and bishops. However, she had lived long enough to witness an historical reevaluation of her father’s rule and her husband’s participation in it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments