By John Kennedy Ohl

In an article in the Pittsburgh Courier on April 15, 1944, correspondent Billy Rowe, who was covering the activities of the 93d U.S. Infantry Division (Colored) in the battle for Bougainville Island in the South Pacific, described a skirmish involving K Company, 25th Infantry Regiment. “A company of the 93rd Division elements fighting here ran into an ambush early this week and all hell broke loose,” Rowe wrote. “Under the command of Captain [James] Curran, the outfit moved out of the perimeter from the base of Hill 250. Its mission was to set an ambush to attack a Japanese force retreating along a known trail. Some 1400 yards out the company was itself ambushed by an unestimated Nipponese force. Caught in a horseshoe, the company was fired upon from three sides.

“In a heated cross-fire the Tan Yanks with their one white scout, shot their way out of the trap, killing an unknown number of Japanese. Sixteen of our soldiers were wounded in this encounter with six killed, including an officer.”

Rowe’s story provided only the bare outline of the skirmish and did not indicate that it had any significance beyond that of other firefights during World War II. As it developed, however, the experience of K Company became a source of considerable controversy and ultimately influenced the conclusions the U.S. Army hierarchy drew about the use of African-American combat troops for the remainder of the war.

African Americans have participated in America’s wars since the establishment of the colonies. They served in the local militias in the colonial wars against Native Americans and the French and Spanish. They fought both with and against the British during the Revolutionary War. They stood with Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, and during the Civil War nearly 200,000, organized into 165 Federal and state regiments and rallied against the Confederacy.

In 1866, Congress created six African-American regiments in the Regular Army. Shortly after, they were consolidated into the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Composed of white officers and African-American enlisted men, these regiments helped pacify Native Americans on the western frontier.

At the end of the century, African-American regiments fought in Cuba in the Spanish-American War and against insurgents in the Philippines. Later, the 10th Cavalry joined Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing’s punitive expedition into Mexico in 1916 in pursuit of the rebel Pancho Villa. While often experiencing discriminatory treatment at the hands of their white officers and comrades, the African Americans were good soldiers. Their desertion rate was much lower than that of whites, and they regularly distinguished themselves in battle.

During World War I, 380,000 African Americans served in the army. Most were assigned to segregated service units and used as menial laborers, although two African-American divisions, the 92nd and 93rd Divisions, were formed. The four infantry regiments of the 93rd Division were assigned on an individual basis to the French Army and won the praise of the experienced French officers who directed their operations. The 92nd Division fought as part of the American Expeditionary Forces. When the division entered the front lines, it experienced some initial difficulties. However, as the men became accustomed to trench warfare there was noticeable improvement in the division’s performance.

Many of the 92nd Division’s problems could be attributed to incomplete training, shortages of equipment, poor cohesion growing out of the resentment of many white officers at being assigned to an African-American unit, and low morale sparked by the blatant racism the men had been subjected to while training in the United States. Most Army officers, however, placed the blame for the division’s shortcomings on the African Americans themselves. In his memoir, Lt. Gen. Robert L. Bullard, commander of the Second Army, branded African Americans “hopelessly inferior” and warned that “if you need combat soldiers … don’t put your time on Negroes.”

Bullard’s views were reinforced by studies produced by the Army War College. A 1925 study titled “The Use of Negro Manpower in War” epitomizes the virulent prejudice toward African Americans that infected the interwar army. Mirroring the scientific racism of the day, it stated: “In the process of evolution … the American Negro has not progressed as far as other sub species of the human family … The cranial capacity of the Negro is smaller than whites’ … The psychology of the Negro … [is] based on heredity derived from mediocre ancestors, cultivated by generations of slavery … In general the Negro is jolly, docile, tractable, and lively … In physical courage [he] falls well back of whites … He is most susceptible to ‘Crowd Psychology.’ He cannot control himself in fear of danger … He is a rank coward in the dark.”

From the experience of past wars, the study continued, “The Negro has made a fair laborer,” but as a fighter “he has been inferior to the white man even when led by white officers.”

Separate But Equal in the 1940s

As the United States prepared for war in the early 1940s, African-American leaders, seeing military service as a means to improve conditions for their race, demanded that African Americans serve in all aspects of the war effort. With the growing political clout of African Americans, especially in the North, they could not be ignored. Moreover, the army needed large numbers of men, and there simply were not enough volunteers to flesh out its ranks.

The marriage of these political and military exigencies led a spokesman for President Franklin D. Roosevelt to announce on October 9, 1940, that the number of African Americans in the army would approximate their percentage of the population as a whole, that they would be eligible for all branches of the service, and that they would be eligible for officer training. It was made clear, however, that the employment of African Americans would take place within the traditional pattern of segregation. Any change to the “present system,” the War Department stated in a memorandum issued a week later, would damage morale and impair preparations for national defense.

During World War II, hundreds of thousands of African Americans served in the U.S. Army. Close to 75 percent were assigned to the Engineer, Quartermaster, and Signal Corps, where they unloaded ships, moved supplies and ammunition to front-line troops, and built roads and bridges. Another 10 percent were in other service branches such as the Medical Corps. Only 15 percent were placed in combat units. They included the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, the 2nd Cavalry Division, the 24th Infantry Regiment, tank and tank destroyer battalions, antiaircraft, coast artillery and field artillery battalions, and combat engineer battalions.

The First African-American Division: the 93rd

The 93rd Division was the first African-American division to be formed. Consisting of the 25th, 368th, and 369th Infantry Regiments and various support units, it was activated at Fort Huachuca, Ariz., on May 15, 1942. During 1942 and 1943 it underwent training, beginning with basic training in Arizona and extending through maneuvers in Louisiana and California. In general, the division received mediocre evaluations as it progressed through its training cycle, and at one point it was given an unsatisfactory rating.

The 93rd Division experienced the training problems common to all divisions during World War II as well as problems that white divisions did not have to face. From the outset, its progress was hindered by the low educational level of the troops. The army placed soldiers into one of five categories based on their scores on the Army General Qualification Test, which measured educational achievement, not native intelligence, as some assumed.

As a group, African Americans tested lower than whites, reflecting their limited opportunities for schooling. Only 0.1 percent of the men in an African-American division were in Class I, the highest category, while in a white division the average was 6.6 percent. Almost 45 percent were in Class V, the lowest category, which in peacetime would have denied them entry into the service. In contrast, only 8.5 percent of the men in a white division were in Class V. As a result of the educational deficiencies of African-Americans, portions of the training cycle had to be repeated, extending the training period for the division to nearly twice that of a white division.

White Officers for African American Soldiers

Leadership was an additional problem. In 1941, only 0.35 percent of the African Americans in the army were officers. As their numbers grew after Pearl Harbor, there was a tendency to assign them to service units in the belief that they did not possess the leadership ability to command troops in battle. Nevertheless, nearly 300, or approximately one-fourth, of the officers in the 93rd Division were African Americans when the division was activated, and during 1943 the number increased to about one-half. All were in junior positions, and their opportunities for advancement were severely limited, leaving them resentful and frustrated.

According to army practice, African Americans were forbidden to outrank or command white officers serving in the same unit, creating artificial professional and social distinctions between the division’s African American and white officers and making it highly improbable for a talented African-American to rise above the rank of first lieutenant. Indicative of the army’s policy, in the 25th Infantry in April 1944 only nine officers out of 44 with the rank or captain or above (the regimental chaplain, six surgeons, the regimental orientation officer, and a company commander) were African American.

White officers in the division generally had a low opinion of African-American officers. Major Robert Cocklin, a white artillery officer, later reported that many had gained their commissions only because of “a certain amount of informal or unofficial relaxation of standards … in order to permit the selection of the required number of Negro officer candidates for commissions.” Once they joined the division, they “were sometimes assigned to duty with troops, without the best possible background and training for that job” and undermined morale by seeking “to hide their deficiencies by claiming discrimination.”

Lieutenant Colonel Earl Smith, the division surgeon in 1944, expressed similar views. In commenting on the African-American officers of the 318th Medical Battalion, he wrote that they “suspect every white officer of race prejudice and ulterior motives. These officers cannot stand pressure or take criticism.”

The 93rd Division’s top echelon, convinced that whites made better leaders than African Americans, demanded that as many white officers as possible be assigned to the division. Often, though, their attitude and caliber were not always conducive to producing a highly efficient unit. Wanting to serve with white units, many resented their assignment to an African-American unit. They did not like African Americans and did not relish fighting alongside them. In some cases, they were rejects from other divisions and, in the minds of those they led, would likely blame anything that went wrong on their troops to salvage their own careers.

Certainly not all white officers in the division were bigots or rejects. Some dealt equitably with African Americans and did well as commanders and staff officers. Many of these officers, however, did not stay with the division. Under an army rotation policy adopted in 1943, a white officer who had been in an African-American unit for 18 months and had been rated “very satisfactory” could request a transfer.

Discrimination, Inactivity Lead to Low Morale

The leadership problem weakened the morale of the 93rd Division. Segregation and racism at its Fort Huachuca training center had the same effect. The separate hospitals, theaters, post exchanges, service clubs, and churches set aside for African Americans were generally substandard to those provided for whites and became a constant source of irritation to African Americans, who believed they were victims of prejudice. Conditions off base were just as harmful. Fort Huachuca was located in an isolated part of southeastern Arizona, and military authorities thought its considerable distance from any sizable white community would minimize complaints about a large number of African-American troops in the state. However since more than 15,000 African Americans reported to the fort by the fall of 1942, fears of racial conflict grew among Arizonians. Bisbee, 35 miles away and the closest town to the fort, was placed off limits for a time—at its own request—to nonresident Fort Huachuca personnel. Other southern Arizona towns such as Douglas, Nogales, and Tucson were no more ready to welcome African Americans and were closed, or at least parts of them, to soldiers from the fort.

As the 93rd Division progressed through its training cycle, it seemed unlikely it would be sent into combat. Outside of the 99th Pursuit Squadron and a few antiaircraft battalions, virtually no African-American combat units had been committed to battle, and the War Department showed little interest in sending others overseas. Like the 93rd Division, most were marked by many “slow learners,” weak leadership, and low morale. The War Department was therefore inclined to convert them into service units to meet the support needs of the growing overseas armies. These armies also needed ground troops, but African-American combat units remained in the United States, unwanted by theater commanders who recited all the criticisms levied against African-American troops since World War I.

Pressure Grows to Use the 93rd in Active Combat

Finally, at the end of 1943, growing controversy over the failure to deploy African-American combat units to war zones prompted army planners to consider sending the 93rd Division to an active theater. For months, African-American political and religious leaders, the African-American press, and the War Department’s Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies had been calling for African-American units to be committed to battle in the belief that their sacrifices on far-flung battlefields would further racial equality at home.

Looking to one of the Pacific areas as a possible destination, the War Department queried Lt. Gen. Millard Harmon, commander of Army Forces in the South Pacific, about his willingness to accept the 93rd Division. He replied that he could better use replacements and service units, but appreciating the War Department’s desire to utilize the division in an overseas assignment, he reluctantly said he would find some role for it.

During January and February 1944, the various elements of the 93rd Division moved from San Francisco to Guadalcanal Island in the southern Solomons. As they arrived, many white officers in the theater were openly skeptical of the division’s value as a combat unit and, as reported by Brig. Gen. Leonard Boyd, the assistant division commander, were not “anxious to give these negro troops an impartial opportunity to demonstrate their worth.” Consequently, the division’s units were separated from each other and assigned to garrison and labor duties in rear areas.

However, factors were already at work that would soon place some of the 93rd Division’s elements in combat. In the weeks after it had been dispatched overseas, African-American leaders stepped up their demand that African-American units be committed to battle. Concurrently, the use of African Americans in battle threatened to become an issue in the upcoming election. Sensing a vulnerable flank for the Democrats, Congressman Hamilton Fish, a Republican from New York, declared in February 1944 that African Americans should have “the same right as any other Americans to train, to serve, and to fight in combat units in defense of the United States in this greatest war in its history.” Fish had been an officer with the 93rd Division in World War I, and his blast indicated the Republicans would hammer away at Roosevelt on the army’s dilatory utilization of African-Americans in combat in an attempt to pick up African-American votes in what looked to be a close election.

Convinced the use of African Americans in combat was now the preeminent racial issue in the army, Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy took the lead in getting them into battle. Acting more as a bureaucrat than a reformer, he recommended to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson on March 2, 1944, that African-American troops be introduced into combat as soon as possible.

McCloy wrote the Secretary of War: “With so large a portion of our population colored, with the example before us of the effective use of colored troops (of a much lower order of intelligence) by other nations, and with many imponderables that are connected with the situation, we must, I think, be more affirmative about the use of our negro troops.”

Despite qualms about the likelihood of African Americans ever measuring up to whites as soldiers, Stimson granted his approval as part of a larger “national policy” to determine whether African-American ground units could endure the rigors of combat. Several days later, War Department Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall instructed Harmon to make early use of elements of the 93rd Division in combat. Shortly afterward, Harmon decided to send a regimental combat team, centered on the 25th Infantry, to Bougainville in the northern Solomons.

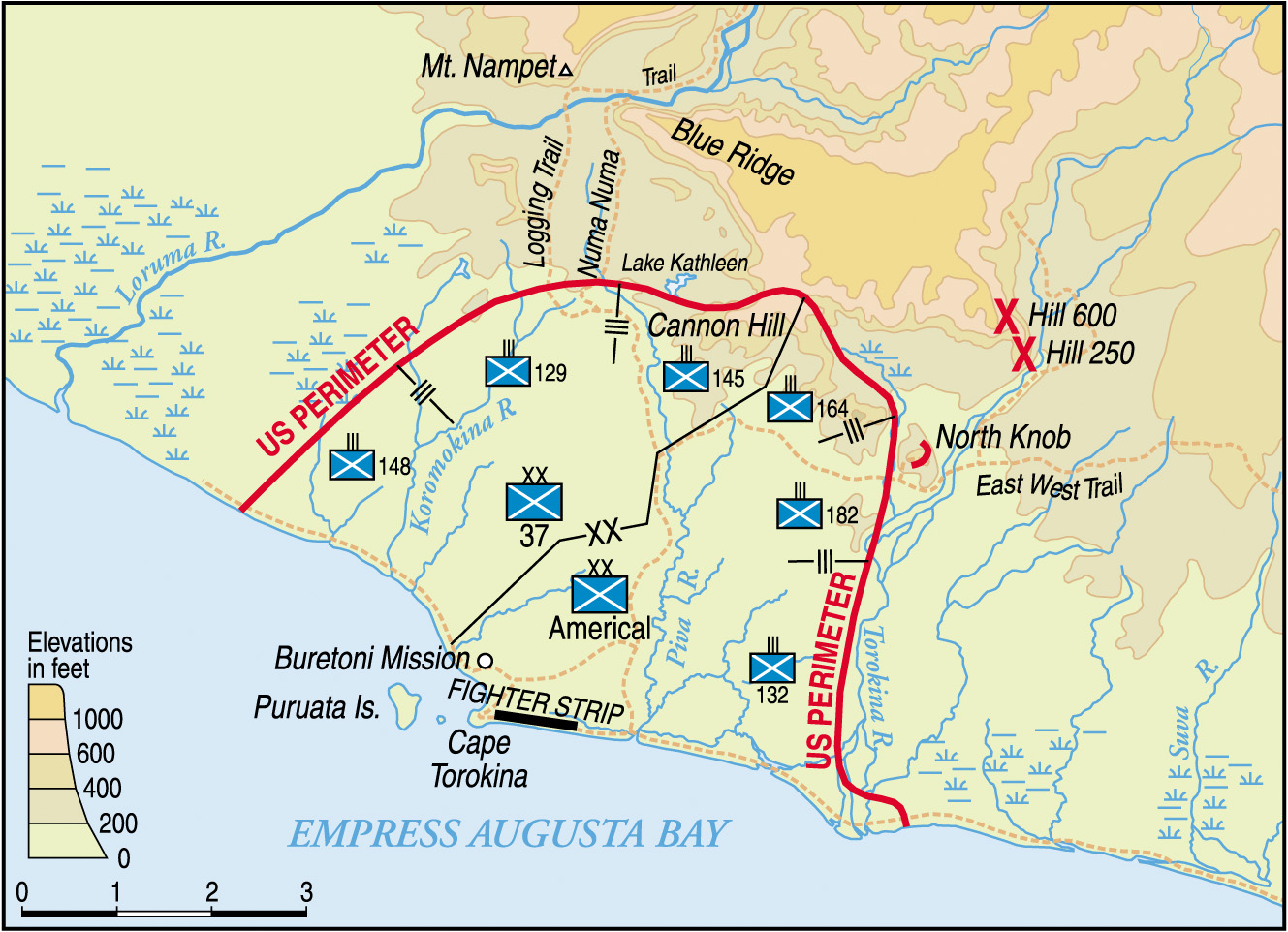

The previous November, troops from the U.S. 3rd Marine Division and the Army’s 37th Infantry Division had landed on the west coast of Bougainville at Empress Augusta Bay. Because the Japanese had more than 60,000 troops defending Bougainville and nearby islands, and because the island’s natural features—high volcanic mountains, dense rain forests, swampy areas—favored the defense, the Allied high command decided against seizing the whole island. Instead, it chose to carve out a lodgment, establish a defense perimeter, and build airfields for raids against Japanese bases to the north.

By the middle of December, when the army’s Americal Division replaced the Marines, the perimeter had been completed. The two American divisions were organized into the XIV Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, and charged with defending the airfields. In March 1944, a Japanese offensive to eliminate the lodgment was thwarted, and thereafter, except for aggressive patrolling by the Americans, both sides adopted a live-and-let-live attitude.

Finally, a Call to Action

The 25th Regimental Combat Team was not the first African-American unit to see combat on Bougainville. The 1st Battalion of the 24th Infantry Regiment had arrived at the end of January 1944 and for several weeks performed service functions. After Harmon received the War Department’s request to employ African Americans in combat, the 1st Battalion was attached to the 148th Infantry Regiment of the 37th Division. On March 11, the 1st Battalion took up a position between two of the regiment’s battalions, engaging in a number of actions over the next several days before passing to the control of the Americal Division.

During their first stint at the front, the men of the 24th Infantry were a bit “trigger happy” and “unreliable and timid in their patrolling,” prompting corps headquarters to rate the battalion “unsatisfactory for offensive operations.” However, as the battalion gained experience, its performance “progressively and noticeably improved” and its combat efficiency was raised to “good.”

Even before the 25th Infantry received orders to deploy to Bougainville on March 22, Washington was becoming nervous about its introduction to combat. Reports of the 24th Infantry’s first action had already appeared in the New York Times, and the War Department wanted the 93rd Division’s first combat experience, which would likely be headlined in the African-American press, to go smoothly. Thus, on March 28 Chief of Staff Marshall told Harmon that the division’s elements should be given combat assignments only after adequate preparation and that the War Department should be kept informed of their progress.

Harmon replied that the 25th Infantry would not be sent immediately into combat as a unit. Rather, its battalions would be attached to seasoned white units and used in limited operations like patrolling or mopping up isolated groups of Japanese.

The 25th Infantry, commanded by Colonel Everett M. Yon, left Guadalcanal for Bougainville on March 26 and landed at Empress Augusta Bay two days later. On March 30, it was placed under the control of the Americal Division, which held the eastern half of the Allied perimeter. Following Washington’s instructions that the regiment should be eased into combat under the guidance of veteran units, Maj. Gen. John Hodge, commander of the Americal Division, assigned each of the 25th Infantry’s battalions to a regiment in his division. During the next days the 1st and 2nd Battalions engaged in their first combat, participating in patrols and pursuing Japanese troops retreating along the Laruma River. In these actions the regiment suffered its first casualties, and both battalions performed adequately considering they were green troops.

K Company Prepares an Ambush

The 3rd Battalion, which was attached to the 164th Infantry Regiment, was the last of the regiment’s three battalions to see action. On April 5, a patrol from K Company discovered a trail about 3,000 yards from Hill 250 that the Japanese were apparently using to shift troops at night. Later that day, Colonel Crump Garvin, commander of the 164th Infantry, decided to have K Company set up an ambush the next day on the trail between the west and east forks of the Torokina River.

K Company was commanded by Captain James J. Curran, a white officer who had been in charge of the company for more than 18 months and was highly regarded by Yon “for his ability and attention to duty.” All of Curran’s platoon leaders were African Americans. K Company was to be supported by a machine-gun platoon from M Company. Also accompanying the formation were Captain William A. Crutcher and three enlisted men from the 593rd Field Artillery Battalion, who were to act as artillery observers; an officer and an enlisted man from the 161st Signal Photographic Company; and Sergeant Ralph Brodin, an intelligence specialist from the 164th Infantry. Brodin had been a member of the patrol that had discovered the trail on April 5 and was to serve as a guide. Except for Crutcher, Brodin, and the two men from the photographic company, the attached personnel were African American. In all, the reinforced company numbered 180 officers and men.

During the evening of April 5, Lt. Col. William Considine, commander of the 1st Battalion, 164th Infantry; Lt. Col. George T. Coleman, commander of the 3d Battalion, 25th Infantry; and Curran briefed K Company officers and sergeants on the mission. According to Curran’s plan, the 1st Platoon would be in the lead, followed by a light machine-gun section and the company headquarters. Behind them were the 2nd Platoon, a second machine-gun section, and the 3rd Platoon. The 2nd Platoon had flank security, and the 3rd Platoon responsibility for rear security.

The Ambush is Sprung

K Company left its bivouac area at the base of the north side of Hill 250 at 0645 in the morning of April 6. Anxious to reach the trail early so his men would have time to “set a good ambush,” Curran quickly pushed across the Torokina River and took only “a few short breaks,” even though the “going was tough” because of the narrow path and the thick underbrush. At 1245 after covering approximately 2,600 yards, the company came across an abandoned Japanese hospital area consisting of several bamboo shelters. At this point, Curran halted the column and ordered 1st Lt. Abner Jackson, comanding the 1st Platoon, to send out four “finger” patrols to reconnoiter the front and the flanks.

Soon after, the patrol on the left front began firing, and the patrol leader, Sergeant Samuel H. Black, returned to tell Jackson that his men had spotted three Japanese about 15 yards away and killed two. Curran started forward with Black to investigate the report, but before they reached the dead Japanese, rifle and machine-gun fire broke out, wounding Black and an enlisted man from his patrol. Uncertain about the size of the Japanese force, Curran ordered the 2nd and 3rd Platoons to take up positions on the flanks of the 1st Platoon.

Everything then fell apart. After a brief lull, firing again broke out as Jackson’s men and the Japanese exchanged shots. Without waiting for Curran’s orders, the 2nd and 3rd Platoons and the machine-gun sections began to fire indiscriminately “in all directions at imaginary targets.” Since all of Jackson’s patrols had not yet returned to the main body, Curran ordered a cease-fire to keep the Americans from killing some of their own men. After a brief respite, there was another burst of Japanese machine-gun fire. Curran’s men again resumed their firing, and men cried out that they were wounded. Segeant Brodin later recalled that the Japanese added to the confusion by “yelling and scared the hell out of the boys.”

Curran, fearing his company might lose its cohesion, ordered his flank platoons to close up on the center. However, as they moved toward the 1st Platoon, some of the men fired sporadically toward the position of the 1st Platoon, now caught in a crossfire between the Japanese and its sister platoons.

The Questionable Withdrawal of the 1st Platoon

Curran then made plans for the 1st Platoon to withdraw and man a defense line about 75 yards to the rear through which the company could retire. By this time, many of Jackson’s men, fired upon from several sides, were withdrawing on their own. As later reported in an investigation of the incident; “Several men ran toward the rear upright almost shoulder to shoulder; some came back in a crouched position; some came crawling through the brush; and some crowded into the lines of the 2d and 3d Platoons.”

Jackson’s platoon sergeant, Edward Dennis, pulled off his pack, dropped his rifle, and “disappeared,” fleeing to the Torokina River. There he was met at 1700 by Coleman, who had come forward from Battalion Headquarters to find out what had happened to K Company. When asked by the battalion commander about the remainder of his platoon, Dennis replied, “Platoon, I had trouble getting myself out.” Dennis and others who had made their way to the river told Coleman they had encountered a large body of Japanese, perhaps a regiment, although none said he had actually seen any of the enemy.

The circumstances surrounding the withdrawal of the 1st Platoon are in question. Jackson later reported that his men did not withdraw until he received “an order from a runner” to pull back to a new position in the rear. Curran, meanwhile, said he had not sent a runner before the platoon withdrew. His intention, he said, was to have the 1st Platoon hold its position until the 2nd and 3rd Platoons had joined behind the 1st “to prevent a break in the line on withdrawal” of Jackson’s men.

In all probability, one of the runners around Curran when he was discussing his plans over the radio with Coleman delivered the message to Jackson without waiting for formal instructions from Curran. To the platoon leader, the order, which led to a premature withdrawal, appeared legitimate, although an investigation later reprimanded him for not verifying it with Curran.

Curran Tries to Restore Order

As the 1st Platoon pulled back in “a confused and disorganized” fashion, some in the 2nd and 3rd Platoons, most of whom were unaware of Curran’s orders for the 1st to withdraw, grew increasingly apprehensive and began to fire in all directions. Moreover, some began to gather next to Curran as he tried to make his way to the rear to help Jackson after hearing reports that the 1st Platoon was “not setting up a line.” Concerned that by crowding together his men were presenting the Japanese with easy targets, Curran decided to remain at the front, organize a makeshift defense line, and ask Colonels Coleman and Considine for instructions. They told him to withdraw about 300 or 400 yards so he could reorganize his company and “calm his men down.”

For the next half-hour confusion reigned. Japanese firing, most of it apparently unaimed, continued in brief spurts. The temporary line Jackson had finally established was ineffective as his men were reluctant to “face forward as ordered” and provide flank cover while the 2nd and 3rd Platoons retired. Men from all of the company’s platoons now withdrew at will, ignoring their officers’ orders to hold their fire and form a single line.

As related by Captain Crutcher, “The men kept moving to the rear slowly even though we tried to get them to hold their positions and take up a perimeter defense. They appeared to stand fast until one man moved and all the men around him would get up and start back. The majority of the men in moving back appeared to be careless in their protective measures. Very few retreated with their faces toward the enemy. They would get up and run towards the rear in a crouched position sometimes catching their jungle packs on hanging vines and being thrown to the ground. I observed three or four men at one time who came through the undergrowth in this manner. They appeared to have a wild look their eyes, and seemed to focus on everything and nothing at the same time. Some of the men in coming back would fall in a prone position and get their rifles in a ready position, but in many instances their rifles were pointed in many directions and they did not seem to have a picture in their minds of just where the action and fighting was taking place.”

Walking along the column, which stretched about 100 yards, Brodin told “the men there was nothing to worry about, that there were a few Japs, and that if they held everything would turn out OK.” Curran also made his way up and down the trail trying to calm the men, but to no avail.

Before long there was no front at all. Men simply lay on the ground, firing in all directions, and then crawled backwards in groups of two or three. All the time Curran desperately tried to stop the firing and get his men to maintain some semblance of order.

His efforts, he later wrote, had little effect. “I tried to stop them but they crawled over me and around me leaving me completely in front of the line. I tried to get some of the ones near me to come up and build a line on me but they continued to go to the rear in groups of three or four. By talking to approximately 15 men around me they finally calmed down and stopped firing without regard. The withdrawal of those remaining few was somewhat orderly.” Concluding that none of his men were in front of his position, Curran had Crutcher call for support from the 593rd Field Artillery Battalion. It fired 25 rounds, and all Japanese shooting ceased.

Colonels Considine and Coleman wanted Curran to withdraw a short distance, reorganize, and continue the original mission. After hearing Curran’s report of the confusion in K Company, however, they ordered him to bring the rest of his men back to Hill 250. Curran and those who had remained at his side made it back to the lines of the 164th Infantry without any further action, arriving at 2315, long after the other elements of the company had straggled to safety.

The Fallout from K Company’s Debacle

K Company’s action on April 6 lasted less than an hour and involved, it was later determined, only a squad or two of Japanese. Curran’s losses were 10 killed and 20 wounded. It was also determined that many of the casualties were caused by the indiscriminate firing by the men of K Company. Equally incriminating in regard to its performance, K Company left behind all of its dead as well as a radio, a light machine gun, two automatic rifles, 18 M1 rifles, and three carbines.

Other green units who were new to battle sometimes underwent a similar ordeal. Like K Company, it was not unknown for them to exaggerate the size of the enemy confronting them, shoot at shadows and even their own men, panic in the absence of information about what was facing them, and run away. In contrast to most other units that encountered difficulties in their first battle, K Company was neither forgiven nor forgotten.

The story quickly spread through the Bougainville lodgment that K Company had broken under minimal Japanese fire, showing that African Americans could not be trusted in combat. Sergeant Brodin added fuel to the story when he reported to Colonel Considine, “The boys got excited and confused by the Jap fire and shot at anything that was light complexioned or moved in the brush … We could have stayed and held out easily, but the boys were so scared that the only way to hold onto them was to pull back.”

Brodin added, “The boys were all out for themselves and left the wounded lay until ordered to take care of them.” Summarizing the outcome of the skirmish, Brodin wrote, “White soldiers are afraid that they won’t see the Japs and the colored boys are afraid they might.”

The Lucas Report

Aware of Washington’s interest in the progress of the 25th Regiment, Griswold ordered the Inspector General of the Americal Division, Lt. Col. Frank Lucas, to investigate the skirmish. In addition to using the after-action reports prepared by Curran, Coleman, Considine, and Brodin, Lucas took testimony from 27 witnesses. His investigation showed that the “poor battle conduct of the patrol” was caused by “fright, lack of initiative, and individual desire for self preservation only of the majority of men in the company.” These were aggravated by “(a) The firing of the reconnaissance patrol without orders … (b) The premature withdrawal of the 1st Platoon … (c) The density of the jungle … (d) The unavoidable need for the reconnaissance patrols to return through the line … [and] (e) … lack of leadership and control by all but a few of the Non-commissioned officers.”

At the same time, Lucas praised Curran. His plans, Lucas wrote, “were tactically sound, and well conceived.” Moreover, “when the execution of these plans became confused, Captain Curran acted in a most commendable manner to regain control, and to extract his command without sacrifice, and in so doing he exposed himself to danger without regard for his own safety. Captain Curran abandoned his mission only after he had obtained permission to do so from his Battalion Commander and only when it became impossible to continue his mission.”

In early May, Griswold’s staff prepared a report for Harmon summarizing the performance of the African Americans on Bougainville. With an emphasis on the experience of K Company, it pointed out that the 25th Infantry had shown some merit, but at best its combat efficiency was “fair.” Choosing to gloss over its more creditable actions in a number of engagements, the staff’s report selectively highlighted the regiment’s shortcomings.

Among other things, the report stated: (1) the regiment had little “jungle training” and that while the men “showed willingness to learn” their “ability to learn, and to retain what has been taught, is generally decidedly inferior to that of white troops.” (2) The morale of the officers, especially white, was low, “an attitude that can be traced to the lack of responsibility demonstrated by their junior officers and non-commissioned officers.” (3) “junior colored officers” tend “to make the minimum effort to carry out instructions” and many “do not have control of the enlisted men.” (4) platoon leaders and lower grades lacked initiative and the “presence of high ranking officers, especially whites, is necessary to assure the tackling and accomplishment of any task.” The unstated conclusion was clear: African-American units were unsuitable for combat.

Yon and Boyd Try to Defend K Company

Discouraged by Lucas’s report and the findings of Griswold’s staff, Yon attempted to place K Company’s ordeal in a more balanced context. Responding specifically to the XIV Corps’ findings in a letter to Maj. Gen. Raymond Lehman, commander of the 93rd Division, he pointed out that his 1st and 2nd Battalions had gone into combat with experienced units from the Americal Division at their side. This was not the case with the 3rd Battalion, and in fact K Company was sent on a patrol with only one combat-seasoned man, Sergeant Brodin. Previously, Yon added, Curran’s company had been rated as one of the three best in the regiment and, in Yon’s view, “had this organization been given prior instruction and been accompanied by an experienced platoon of the 164th Infantry in its initial action, the results would have been far different.”

The experience of K Company, Yon argued, was no different from that of many other units when they were committed to jungle warfare without “proper seasoning.” He wrote that even battle-tested units could have the same experience: “Early in May a company of the 182d Infantry, a veteran of two years of jungle warfare, encountered an inferior force of the enemy east of the Saua River, became disorganized, and returned to the perimeter … after darkness.” While considered “regrettable” by corps headquarters, little was made of the incident in contrast to the controversy surrounding K Company.

Boyd also tried to cushion the XIV Corps’ findings. In a letter to Maj. Gen. John Hull, head of the Operations Division in the War Department General Staff, he suggested that most of the 25th Infantry’s problems could be traced to the “low IQ level” of the enlisted men and its “weak colored junior officers.” However, refusing to concede that African Americans were suitable only for labor duties, he concluded that an African-American division, given troops “of an IQ level comparable to white divisions” and “average officers either white or mixed,” could be “developed into a combat organization capable of relieving spear-head troops after initial combat and possibly developing into shock-troops themselves.”

Yon’s and Boyd’s explanations carried little weight in Washington. The General Staff sent Griswold’s report to McCloy, and in a cover letter forwarding it to Stimson, the Assistant Secretary, attempting to put the best face on his recommendation that African-American ground units should be committed to battle, wrote, “On the whole I feel the report is not so bad as to discourage us … It will take more time and effort to make good combat units out of them, but in the end I think they can be brought over to the asset side.” Stimson was not impressed. His only comment was, “Noted—but I do not believe they can be turned into effective combat troops without all officers being white.”

In the meantime, the 25th Infantry’s battalions continued to engage in patrol actions under the supervision of the Americal Division’s regiments. At the end of April, they were finally brought together as part of a provisional brigade in the 93rd Division. Between May 20 and June 12, the regiment was pulled out of the line and sent to the Green Islands. Yon expected the regiment would soon see “intense combat duty” that would make “the past two months seem like child’s play,” but his expectation did not materialize. The 93rd Division was placed under the control of the Eighth Army in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). Influenced by the story of K Company, it assigned the division to garrison and labor duties.

The 93rd Division Gets Slandered

As the months passed, the story of K Company took on an exaggerated character. Repeated again and again throughout the Pacific, oftentimes with a malicious intent by bigoted whites to prove that African Americans were inferior soldiers, the experience of K Company was inflated encompass the entire 25th Infantry and even the whole 93rd Division. The division, it was said, was a poor fighting unit with weak African-American officers and was held together only by its white officers. In its most extreme form, rumor had it that the division had been assigned a beachhead at Bougainville, had broken under fire, and run to the rear, causing many whites to be killed by the Japanese.

In early 1945, Walter White, an official with the National Association of Colored People, who was serving in the Pacific as a reporter for the New York Post, heard many of the rumors about the “failure” of the 93rd Division at Bougainville and reports that the division was destined to service in backwater areas. Angered by what he saw as the army’s racist perception of the division, White set out to find out what had happened at Bougainville and launched a campaign to have the division committed to the major battles being fought in the SWPA so that African Americans could demonstrate they could fight.

Writing to Roosevelt in February, White charged that the division had been slandered by the rumors surrounding the 25th Infantry at Bougainville. K Company’s experience, he stated, was an exception and should not be used to smear African-American troops or to exclude them from major combat operations.

On March 1, 1945, White met with General Douglas MacArthur, Commander, SWPA, to discuss the 93rd Division. A week later, in a memorandum to Roosevelt, he stated that MacArthur showed “extreme annoyance and disgust” at the “false and ridiculous” notion that African Americans were too cowardly to fight effectively. The general added that the 93rd Division would be used in combat “providing circumstances warranted,” a statement White interpreted to mean that it would soon see action. MacArthur, however, had no intention of using the 93rd Division in a major combat role. Accepting his staff’s finding that it suffered from low morale and weak leadership, he sent most of its elements to Morotai in the Netherlands East Indies. There they finished the war providing support services for Australian troops and hunting down the remaining Japanese on the island.

World War II Didn’t Change Much for African-American Soldiers

The combat record of other African-American ground units during World War II is mixed. Individual tank and artillery battalions served with distinction in the European Theater of Operations (ETO). At the same time, the 92nd Division underwent difficult experiences in Italy that confirmed the negative perceptions about African Americans that the high command had drawn from the experience of K Company.

During the war’s final months, 2,500 African Americans, organized into platoons, were assigned to white infantry companies when the ETO’s 12th Army Group was desperately short of riflemen. There was little difference in performance between these platoons and the white platoons they fought alongside, but higher ups disparaged this halting step in integration as too limited to draw any significant conclusions.

World War II had no immediate impact on the place of African Americans in the U.S. Army. Despite ample evidence that most African-American soldiers had performed capably in battle, the army was unwilling to alter its traditional way of employing them. Change would eventually come, beginning with President Harry S Truman’s 1948 Executive Order desegregating the Armed Services. However, its effect was felt slowly, and in the meantime longstanding assumptions about African Americans as soldiers dominated. Asked in 1949 about the wartime performance of African-American troops, General Marshall erroneously described the 93rd Division as a unit whose men on Bougainville “wouldn’t fight—couldn’t get them out of the caves to fight.”

John Kennedy Ohl is a professor of history at Mesa Community College in Mesa, Arizona. He is a graduate of the University of Cincinnati and has contributed to numerous books and magazines.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments