By Edward L. Bimberg

The annals of the United States Marine Corps are filled with the names of mavericks known not only for their fighting skills, but for their offbeat personalities as well. Not the least of these was Maj. Gen. Smedley D. Butler, who in the course of a contentious, adventure-filled 33-year career in the Corps garnered 16 decorations, including two Medals of Honor, while also gaining a well-earned reputation for battling higher authority—often in public.

A Young Start to a Long Career

Butler was born into a prominent West Chester, Pa., Quaker family on July 30, 1881. His father, Thomas S. Butler, was a U.S. congressman and chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee. While there is no evidence to suggest that the elder Butler ever used his considerable influence to promote his son’s career, the Navy Department was certainly aware of his powerful position and may well have taken steps to protect the headstrong Smedley in his many future altercations with his superiors.

When war was declared with Spain in 1898, Butler was just 16 and still in school. Determined to take part in the great adventure, he heard that the Marine Corps had openings for a few new second lieutenants. Since he was still under age (although he looked older), he asked his father to help him enlist. When his father refused, he went directly to Marine Corps headquarters in Washington, D.C., where he introduced himself to Colonel Charles Heywood, the commandant of the Corps. The colonel, of course, knew Congressman Butler, and he also knew that Smedley was lying about his age, but he signed him up anyway. Then and there, Butler became an officer in the Marine Corps.

When his father discovered Smedley’s deception he was understandably upset, but he also admired his son’s patriotic determination and ultimately gave him his blessing. There was no Officer’s Candidate School or Platoon Leader’s Class for young Butler. His military education was left entirely in the hands of a grizzled sergeant major. It only lasted a few weeks, then he was off to Guantanamo, Cuba, where he first heard the whine of enemy bullets and felt the fear and excitement of combat. One minor skirmish was all Butler saw of the Spanish-American War, but it led to a major decision in his life. He made up his mind to remain in the Corps after the war and make military service his lifelong career.

From the Philippines to China

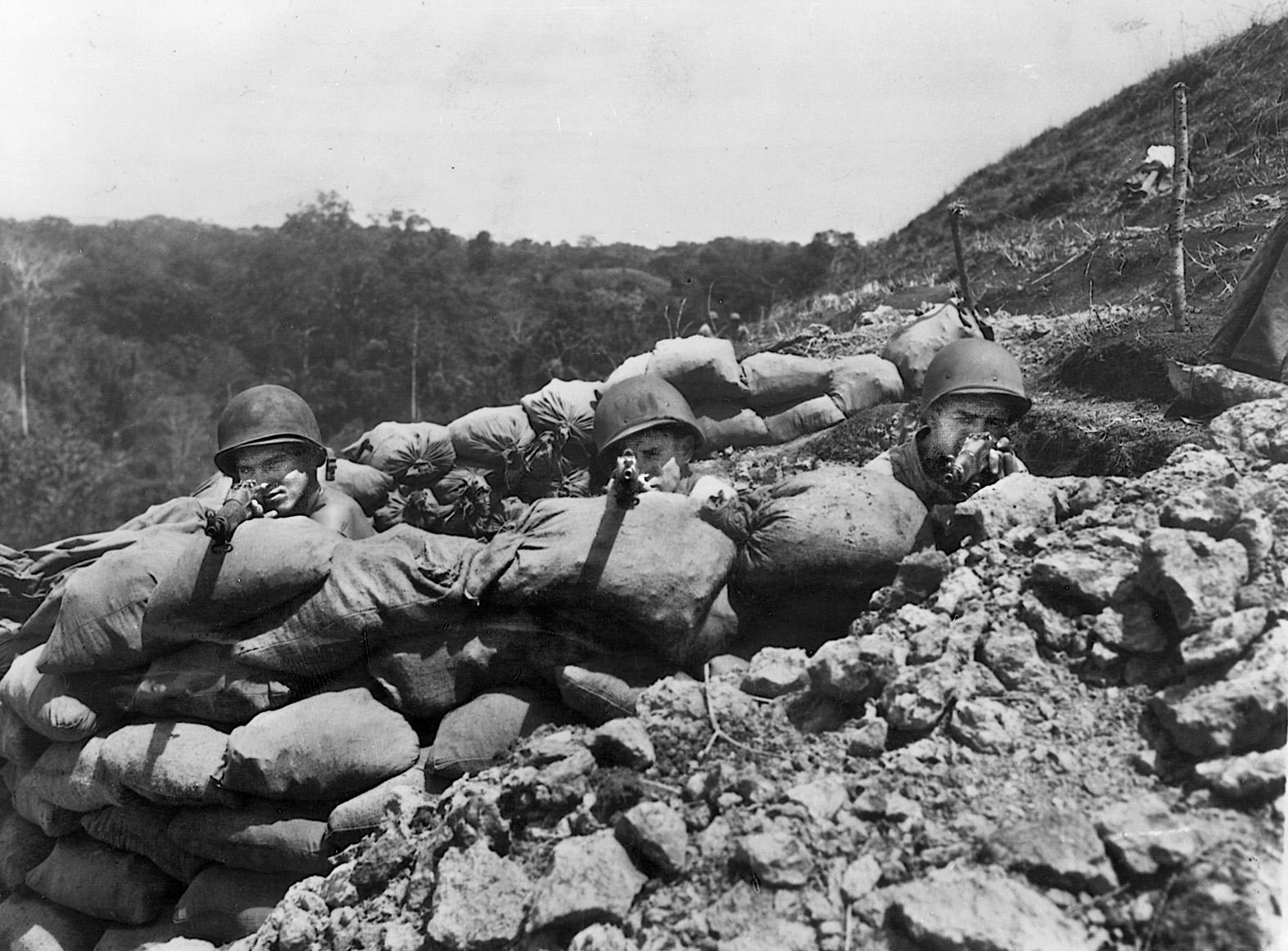

After the war Butler was ordered to the Philippines, where Filipino rebels were waging a brutal guerilla campaign against their American occupiers. The Philippine insurrection may not have been a major war, but like all such affairs it got plenty nasty, and Butler was soon embroiled in his first real firefight. Following a relatively quiet period of garrison life in Manila, Butler’s battalion was ordered to the naval station at Cavite, where some heavy fighting was taking place. Recently promoted to first lieutenant, Butler took over command of his company when the original commander was promoted and soon found himself leading a mission against rebels entrenched outside a nearby town.

In the face of heavy rifle fire, and in spite of his own admitted panic, Butler rallied his company and drove the insurgents out of their positions and through waist-deep rice paddies. It took a while, but the rebels were finally defeated, and the teenage lieutenant could feel that he was a real fighting Marine at last. That was the end of the Philippine campaign for Butler. His battalion returned to the soft garrison life at Cavite, an existence highlighted by cockfights, riding lessons, and visits to a local tattoo parlor. Butler had a huge Marine Corps globe-and-anchor insignia tattooed painfully on his chest, a visible sign of his loyalty and devotion to the Corps.

In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion erupted in far-off China. The Boxers were a fanatical, well-armed movement that had arisen in the cities to oppose the corrupt Dowager Empress and her equally venal government, and they were also ferociously antiforeign. The Marines were sent from the Philippines to join an international expedition to protect their nationals from the depredations of the dangerous zealots. Butler was still young, but he matured rapidly as an officer in China, where he was wounded twice while fighting the Boxers. In Tientsin he was shot in the thigh while helping to rescue a wounded Marine under heavy fire. The wound put him in a field hospital, and while he was recuperating there a promotion board advanced him to the rank of captain—at the still tender age of 18.

Later, during the vicious street fighting in Peking, Butler was hit again. This time the bullet struck him a glancing blow that flattened a button against his chest, causing a nasty bruise and knocking him down. The only medical attention he received was hasty field dressing. Although he was in pain much of the time, he remained on duty until the end of the Boxer Rebellion.

The “Banana Wars”

His service in China was a decisive experience in Butler’s life. It proved once and for all that he had the right stuff and gave him the confidence he needed to carry on with his military career. Although he had little formal military education, while many of his peers were graduates of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Butler now had the courage to disagree openly with his superiors, a characteristic that quickly became the hallmark of—and sometimes a major stumbling block to—his later career. Much of Butler’s professional life was divided between daredevil exploits in minor “banana wars” in Central America and the Caribbean, and quarrels with the Marine brass over a variety of issues, from the proper amount of rations for his men to their misuse as laborers on various government projects.

The pattern for the little wars was set in 1910 when Butler, now a major, was sent ashore in Nicaragua to ensure that Americans were not endangered during the current revolution in that perennially unsettled country. American consular officials left little doubt that the U.S. State Department favored the rebels, and Butler had no hesitation in taking a decisive role in the rebellion. As he later admitted, he took “unofficial command” of the revolt at the point of his men’s bayonets. With the help of Butler and his Marines, the rebels ultimately triumphed and Butler’s battalion returned to its base in Panama.

The Marines’ chief focus in Panama was on safeguarding the ongoing construction of the canal, and Butler’s main role was playing host to a succession of visiting political bigwigs. He also managed to acquire a wife, a Philadelphia society girl named Ethel Peters. For a time, life was good, but the political pot was always simmering in that part of the world. At the beginning of 1914 it boiled over in Mexico, where a nasty little contretemps had arisen between American business interests and the provisional government of President Victoriano Huerta. The Americans complained that Huerta was not doing enough to protect their interests; Huerta, in turn, accused the Americans of trying to foment a revolution against him.

The situation worsened in Mexico and an American fleet under Admiral Frank Fletcher was dispatched to Mexican waters. Butler was ordered to report to Fletcher on his flagship lying off the port of Veracruz. Butler’s first job for Fletcher was a spy mission to Mexico City in civilian clothes and under a false name. The mission, although difficult, dangerous ,and not to Butler’s liking, was a success. He was back in Veracruz in two weeks, the false bottom of his suitcase filled with valuable information on Mexican troop dispositions in the capital. Butler had proven himself as good a secret agent as he was a fighting Marine.

War in Mexico and Haiti

Diplomacy failed to solve the issues between the United States and Mexico. By April there was desultory firing in the streets of Veracruz that soon escalated into full-scale combat. It was urban warfare of the worst sort and Butler, back in uniform, was right in the middle of it. He played a spectacular part in the fighting, leading the Marines personally and exposing himself to enemy fire again and again. The young major’s valor did not go unnoticed; for his service at Veracruz, Butler was awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration. Once again, however, Butler demonstrated his penchant for annoying the Navy brass. He declined the honor, saying it was undeserved. The Navy Department responded to this extraordinary challenge by ordering him to accept the medal and wear it on all appropriate occasions. That was that.

The little war with Mexico ended in 1914 with the defeat and exile of Huerta and the election of a new president who was friendlier to the United States. The peace proved short-lived. Another crisis popped up in the Caribbean the very next year. The Republic of Haiti was, as usual, ablaze with revolution. Haiti was much too close to the United States for comfort, as far as the administration in Washington was concerned. The Marines, including Butler and his battalion, were dispatched to suppress yet another Latin American revolt.

The area around Port-au-Prince, the capital, was quickly pacified, but remnant bands of revolutionaries roamed the mountainous north. Calling themselves “Cacos” after the local bird of prey, the revolutionaries were terrorizing farmers in the lowlands. The Marines were given the task of bringing the Cacos under control. Once again, Butler was in his element. At every opportunity he volunteered to lead expeditions into the mountains in often futile attempts to find and disperse the elusive bands. On those occasions when he met with some success, Butler seldom failed to let his superiors know what should be done. This did not win him any points with the higher-ups.

Breaking Fort Riviere

Eventually, after Washington had dispatched enough troops to Haiti, things quieted down, even in the north. There was just one more tough nut to crack: Fort Riviere on Black Mountain, the last bandit stronghold in Haiti. Built by the French when they occupied the country in the latter part of the 18th century, the fort was a real stronghold, with thick stone walls and crenelated battlements, situated at the summit of a 4,000-foot-high mountain. To ensure its impregnability, three sides of the fort’s wall had been built into the nearly vertical cliffside. The fourth side, where the only sally port was located, could be approached along a gentler slope. The official viewpoint was that it would take at least a regiment with strong artillery support to capture the position.

Butler disagreed. He told his peers he could take Fort Riviere with just 100 picked men. When Colonel Eli K. Cole, his regimental commander, heard of his boast, he surprisingly gave Butler the opportunity he desired. Cole told Butler to pick the men he wanted and go to it. Butler, of course, was delighted. His plan for the assault on the fort was to split his group into four small companies, three of which would approach it from the steep side. There they would find positions as near to the walls as they could and open fire, drawing the defenders’ attention away from the vulnerable fourth side. Butler and the rest of the men, with two machine guns covering them, would then charge through the sally port.

It was a plan typical of the man—bold to the point of rashness. It might have worked, except for one thing. When Butler and his party actually reached the sally port, they found it completely blocked with stones and bricks. Now what? With the machine guns forcing the enemy to keep their heads down, Butler, his senior NCO, and his orderly scouted around the walls until they found the secret entrance used by the Cacos. It was a drain opening, only about four feet high and three feet thick, tunneling back for 15 feet into the interior of the fort. The lone guard outside the wall scurried down the tunnel after he saw the three Marines approaching and took up a position at the other end of the fort’s courtyard.

It was the moment of truth for the Marines. With the Haitian firing into the tunnel, it seemed suicidal to enter the passageway. Butler later admitted that he hesitated momentarily, but the sergeant, named Iams, took one look at the uncertain major and cried, “Oh, hell, I’m going in!” As Iams ducked into the narrow opening, Butler snapped out of it and tried to follow, but the orderly, Private Gross, elbowed past him and went in next. Butler was third. Bullets went whizzing down the crowded drain.

Miraculously, none of the Marines was hit by the wildly firing rifleman, and Sergeant Iams shot the bandit dead. When Gross and Butler followed, tumbling out of the drain into the courtyard, a large crowd of Cacos was milling about, armed with firearms, machetes, clubs, and knives. The three Marines held off the Cacos for a short but critical time, allowing the rest of Butler’s party to follow the three leaders through the tunnel. There was a wild melee, but Marine firearms and discipline had the situation soon under control. Those Haitians who weren’t put out of action by American firepower either scrambled over the walls and disappeared into the bush, or surrendered. By the end of the morning, Butler had lived up to his boast—Fort Riviere was his.

Butler in High Command

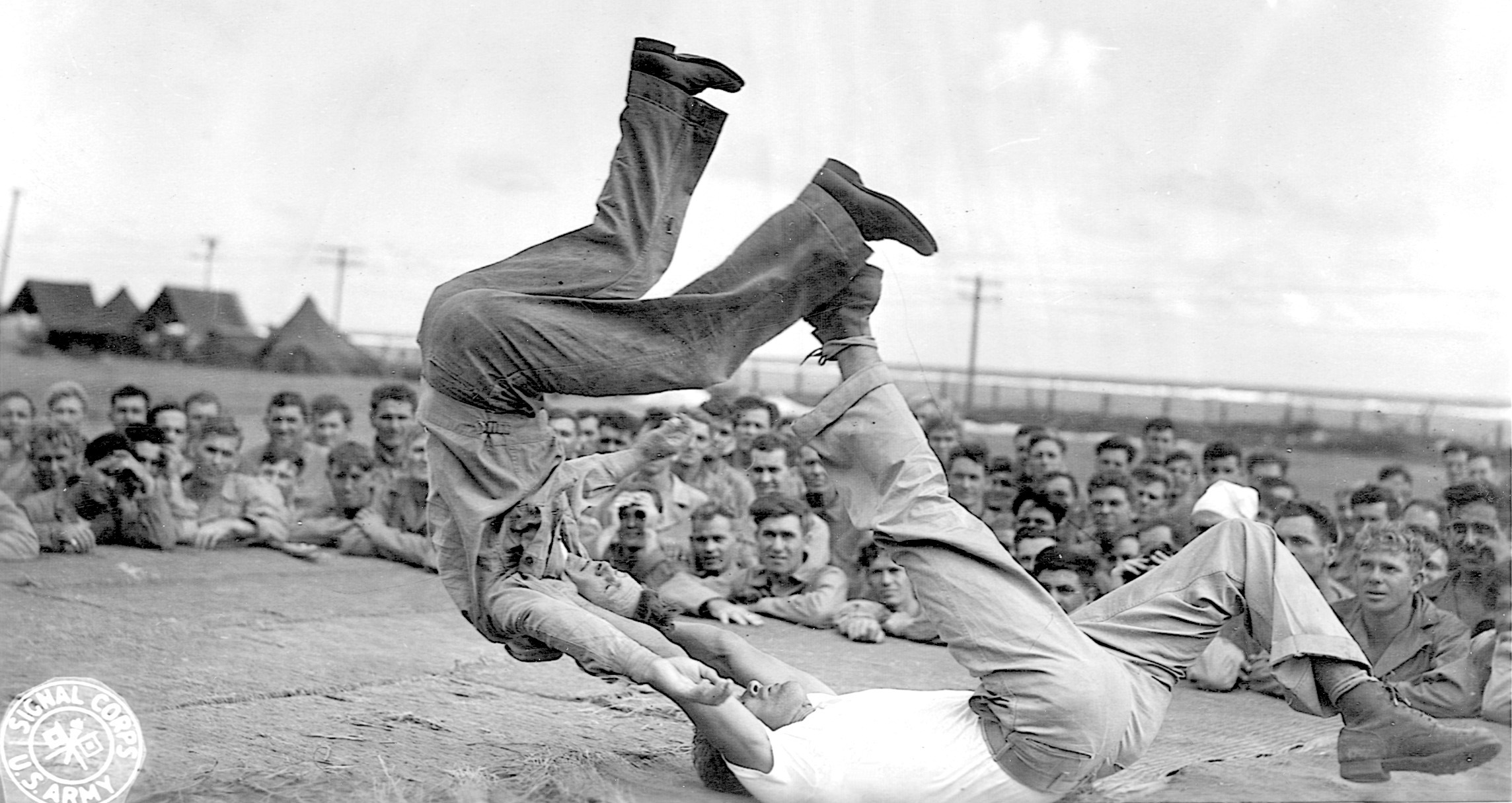

Fort Riviere was the last of Butler’s hand-to-hand, eye-to-eye battle adventures, but not the last of his battles with higher authority. In World War I he pulled every wire he could to get a combat command, but ended up in France as commandant of Camp Pontenzen, a huge swamp riddled with influenza and meningitis that served as the U.S. Army’s reception center for the port of Brest. Long before the war was over, he had turned the notorious hellhole into a model base, and he managed to do so without ruffling too many official feathers—an astonishing accomplishment for the peppery Marine.

After World War I, Butler was promoted to brigadier general and served as commandant of the Marine Corps base at Quantico, Va. Then, on leave from the Marines, he did a stint as public safety director for the city of Philadelphia, before returning to take charge of 5,000 troops who had been sent to China to protect American lives and property during the 1927 revolution. Unlike their long-ago Boxer experience, the Marines were kept out of the fighting this time. Butler played the role of diplomat to perfection, an unexpected reversal of his usual role of short-tempered fighter. When the Marines left China in 1929 all was quiet and Butler, whose men had helped in reconstruction and humanitarian projects, was treated as a hero by the Chinese.

Clashing with the Secretary of War

Butler’s persona as a diplomat did not last very long after he returned to the States. Although he was promoted to major general and resumed his old duties as post commander at Quantico, he was soon involved in petty quarrels with Secretary of War Charles F. Adams. Butler thought the problem was that Adams did not like Marines—he certainly did not like Butler. The squabbles with Adams soon paled in importance when Butler was arrested on January 29, 1931, on charges of “conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline” and “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.”

The charges stemmed from a speech Butler had made at a private club in which he repeated a derogatory story he had heard about Italian Premier Benito Mussolini, who was an ally at the time. When the story leaked, the State Department was embarrassed and Butler was arrested. The diplomats had miscalculated, however. Butler was hailed as a national hero by the American public, while Mussolini was seen as a brutal dictator. The charges were dropped and Butler’s rank and privileges were restored. His major general’s flag was raised again over Quantico.

But Butler was to endure one more snub. When Maj. Gen. Wendell Neville, the commandant of the Marine Corps, died in office, it left Butler as the senior ranking officer in the Corps. He was thus next in line for commandant, but a brigadier general far down the seniority list was chosen instead—with Secretary Adams’ enthusiastic recommendation. Butler had seen enough. On October 1, 1931, he retired after 33 years of high drama and heroic service. The senior officers he had annoyed may have breathed a sigh of relief, but those who had served under him hailed Butler as an authentic American hero. His two Medals of Honor and 14 other battle decorations were more than enough proof of that.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments