By David A. Norris

“Indians! Indians!” The staple warning from countless cliché-ridden dime novels was all too real at dawn of a Colorado morning in 1868. Pickets guarding the camp of Major George A. Forsyth’s U.S. scouts saw a handful of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors making a play for their tethered horses. Seven horses were taken in the surprise dash, but the loss of those animals was nothing compared to the next unwanted surprise. Pouring down from distant hilltops and ridges were several hundred Indian horsemen, bent on overwhelming the small band of three Army officers and 50 civilian volunteers.

One of the most famous clashes of the Indian wars, the nine-day Battle of Beecher Island, was about to take place. It had been long in the making. By 1868, the U.S. Army had shrunk drastically from the massive million-man force of the Civil War years to just over 50,000 troops. Many of the remaining soldiers were tied up doing Reconstruction duty in the southern states, just as accelerating white encroachments on Indian lands in the Great Plains touched off new conflict on the frontier. White hunters slaughtered thousands of buffalo, sometimes to collect buffalo hides or feed railroad builders, but all too often simply for sport. Plains Indian tribes depended on buffalo for food, shelter, and clothing—indeed for their very lives.

“50 First-Class, Hardy Frontiersmen”

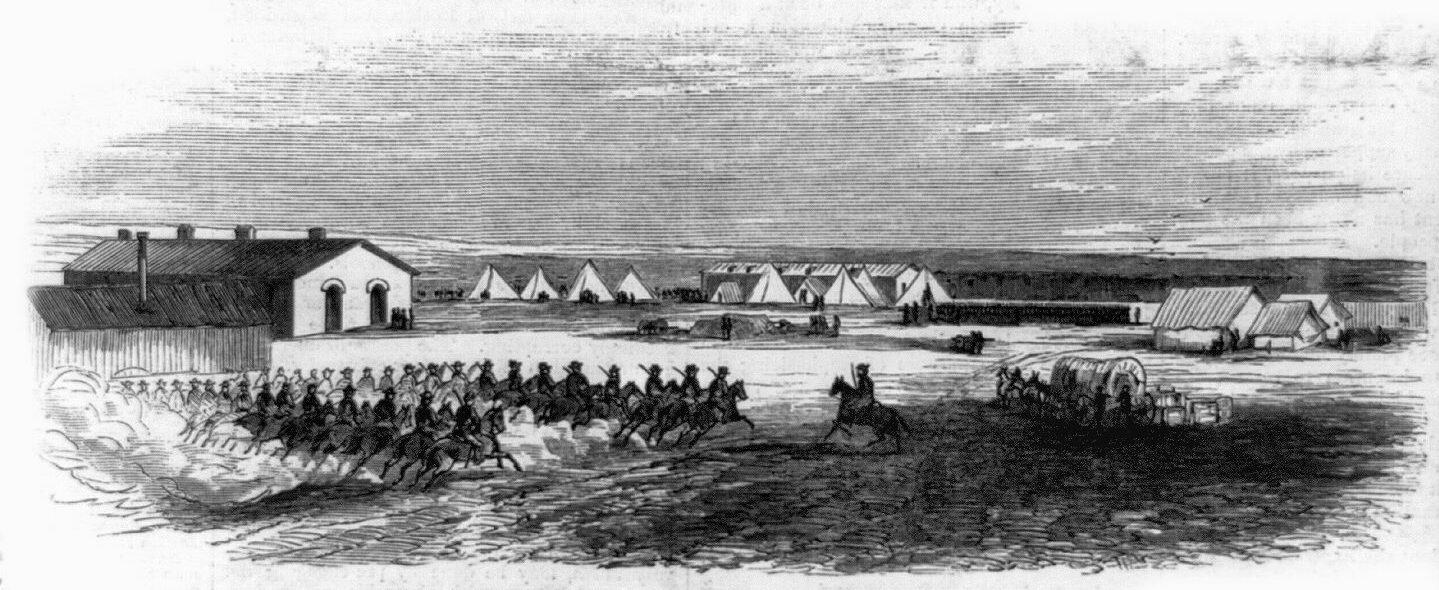

In true guerrilla fashion, war parties of Sioux, Cheyenne, and other tribes began to strike back against the travelers, ranches, and settlements that were threatening to destroy their way of life. As the attacks increased, so did the pressure on the Army to stop them. Responsibility fell to Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, the former Union cavalry leader who now commanded the sprawling Division of the Missouri. Sheridan had too few men to adequately patrol the vast, sparsely populated frontier regions, and some of the soldiers he did have were infantry or artillerymen who had little chance of catching up to the fast-moving mounted war parties of the various hostile Indian tribes.

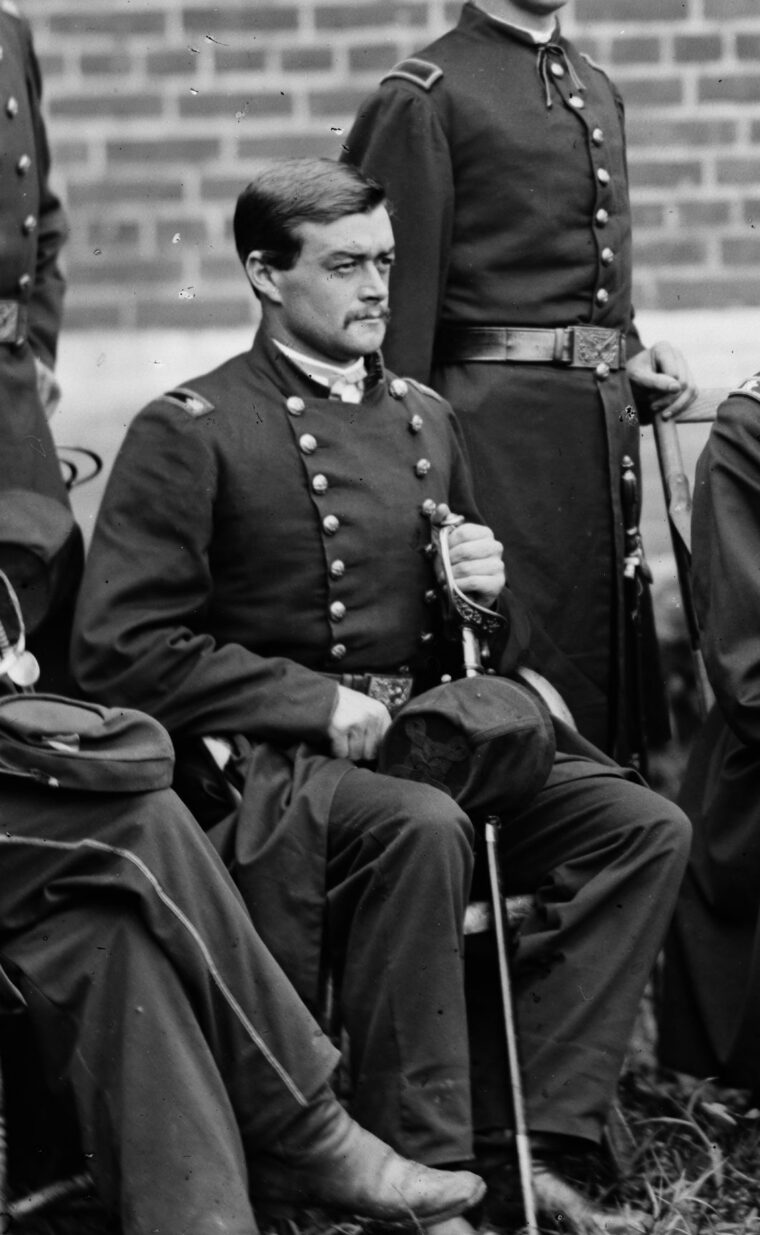

One solution came from Sheridan’s aide, Pennsylvania-born Major Forsyth, who had accompanied Sheridan on his famous ride at the Battle of Winchester, Virginia, in 1864. Forsyth envisioned a picked force of frontier scouts who were familiar with the Indian way of warfare. Sheridan agreed and drafted orders on August 24, 1868, authorizing Forsyth to “employ 50 first-class, hardy frontiersmen to be used as scouts against the hostile Indians.“ Although organized along the lines of a company of cavalry, Forsyth’s scouts were not officially soldiers. They were tallied in military reports as employees of the quartermaster department. Their base pay was $50 a month, and 18 of the men were allowed an extra $25 a month for providing their own horses and equipment. Some of the men borrowed horses from C.W. Parr, the post scout at Fort Hayes, agreeing to pay Parr the extra money.

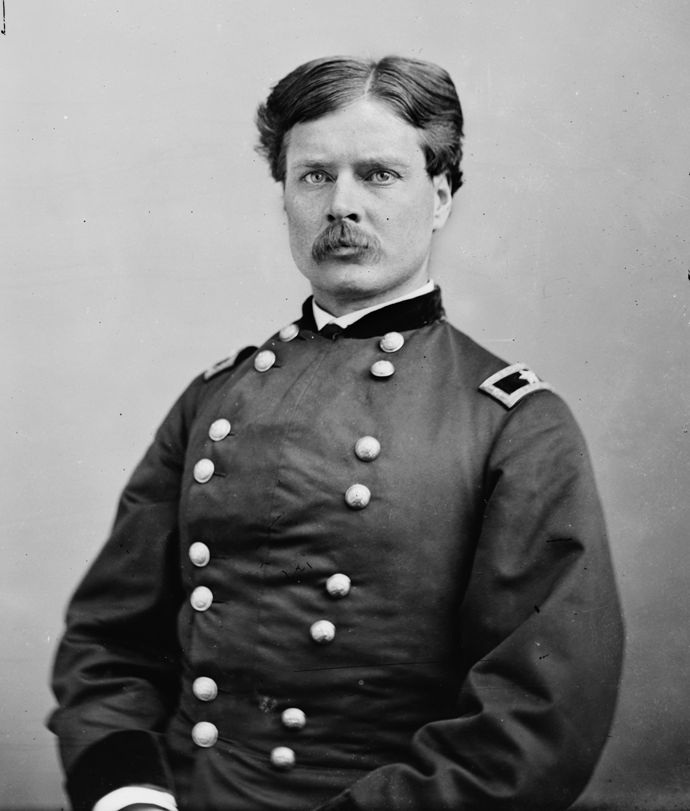

Forsyth’s second in command was Lieutenant Frederick H. Beecher of the 3rd U.S. Infantry. Beecher’s uncle was the famous abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher and his aunt was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Beecher had served in the Union Army and still walked with a slight limp from a bullet wound taken at Gettysburg. Orders had just been drafted for Beecher’s transfer to the Signal Corps, but he intended to finish the upcoming expedition before reporting to his new assignment.

Forsyth appointed Abner T. “Sharp” Grover as chief of scouts and chose William H.H. McCall to serve as sergeant of the detachment. McCall was, if anything, overqualified, having commanded a Pennsylvania regiment during the Civil War. By the end of the war he was a brevet brigadier general and was one of the officers assigned to guard the Lincoln conspirators before their trials. Discharged in June 1865, McCall headed west, where his fortunes worsened. Before being picked as sergeant, McCall was one of the $50-a-month scouts, suggesting that he couldn’t provide a horse for the expedition.

Each rider had 140 rounds for a Spencer repeating carbine, and another 30 rounds for an Army Colt revolver. The seven-shot Spencer repeaters enabled a rate of fire of about 20 shots per minute. Four pack mules carried camp kettles, medical supplies, picks and shovels, coffee and salt, and another 4,000 rounds of ammunition. Doctor John H. Mooers accompanied the scouts as their medical officer. Mooers had served as a surgeon in the 16th and 188th New York regiments during the Civil War, moving to Kansas after the war. He was a contract surgeon, a physician hired on a temporary basis when a regular Army surgeon was not available.

Low on Food

Forsyth left Fort Harker on August 26, arriving at Fort Hays two days later. On August 30, he headed for Fort Wallace, with orders to scout the headwaters of the Solomon River. As they neared Fort Wallace on September 5, Beecher thought he spotted Indians lurking atop a bluff. Forsyth ordered a charge, but as they drew closer to the Indians, they saw that it was only a train of hay wagons headed for the fort. During the charge, scout Wallace Bennett broke his leg when his horse stumbled in a prairie dog hole.

The expedition stayed at Fort Wallace until September 10, when word reached the fort of an Indian attack on a freight wagon train near the western terminus of the Kansas-Pacific Railroad. In the raid, just 13 miles from the fort, two teamsters were killed and some animals taken. Scout G.W. Chambers was left behind to tend Bennett and another man who had fallen ill at the fort, leaving 51 men ready to ride in pursuit of the hostiles.

At the site of the wagon train attack, the scouts picked up the trail left by about two dozen warriors. They headed toward the Republican River, but signs grew thinner until the trail disappeared entirely. Forsyth decided to ride on to the river anyway. Five days after leaving the fort, they reached the Republican River and ran across another Indian trail. Horses, cattle, and heavy loads of tent poles had worn great ruts into the earth. It suggested that the warriors could not travel fast because their families were with them.

By this time, the scouts’ food was running low, and with such a large number of Indians moving ahead of them, there was no game available to supplement the dwindling rations. Grover and McCall advised against heading deeper into Indian territory with such a small force that was running out of supplies. Forsyth, feeling that they were closing in on their quarry, rejected the advice and pushed on. As he wrote later, he felt that “even if we could not defeat them, they could not annihilate us.”

The Native Charge

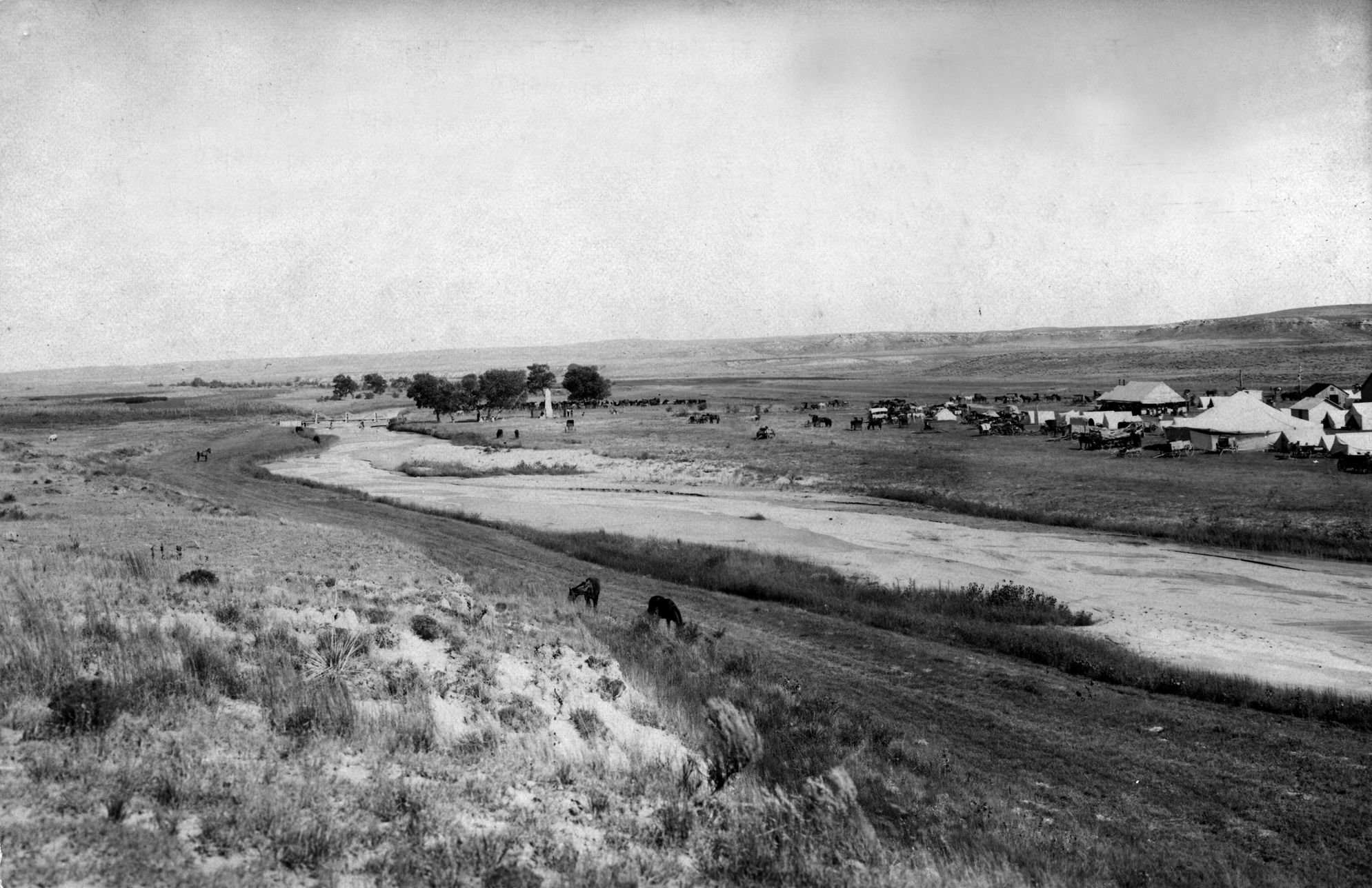

Late in the afternoon on September 16, Forsyth’s party entered the valley of the Arikaree River, a tributary of the Republican River, in Colorado Territory. About five miles west of the border with Kansas, they passed by a low, sandy island, 200 feet long and 40 feet wide. Much of the Arikaree, as usual for that time of year, had dwindled away, leaving only a small stream flowing through the middle of the wide river bed. At the island, which was only a foot or so above the waters, the river split into two streams 15 feet wide and five inches deep. Sage grass grew at the head of the island and a lone 20-foot-high cottonwood tree stood at the foot, with a four- or five-foot high thicket of scrubby willows and alders in between. The horses were worn down from the hard riding and the valley had abundant grass, so Forsyth decided to call an early halt and camp near the river for the night.

Twelve miles away from the scouts’ camp were two large Sioux villages; nearby was another village of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, a fierce warrior society within the tribe, along with some Arapaho as well. Warning reached the villages by accident. A war party had left a day or two before, and some of its members, returning to the villages, had observed Forsyth and his men while on their way back. Word spread quickly through the villages, and about 600 Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors readied themselves for a united attack on the invading force.

Dawn found several hundred mounted warriors poised to rush down upon the camp of Forsyth’s scouts. A small band of warriors, though, made their own plans to stampede the white men’s horses during the night. Led by Cheyenne warriors Starving Elk and Little Hawk, the band included one of the Sioux who had discovered Forsyth’s force. The raiders could not find their quarry until near daylight, when they spotted the campfires in Forsyth’s camp. As Starving Elk and his companions dashed near the picketed horses and mules, “the soft thud of unshod horses’ hoofs came to our ears,” recalled Forsyth. Gunshots rang out from the guards as the Indians, making all the noise they could and waving robes and blankets, rode through the herd to stampede the animals. The animals had been carefully secured, and only a few broke loose from their picket-pins. Starving Elk got away with seven horses, but the raid thoroughly alerted the scout camp, and all chance of surprise was gone.

There was no respite for the scouts. Forsyth remembered that Sharp Grover placed his hand on his shoulder and said, “Oh, heavens, General, look at the Indians!” Grover’s statement was a mild reaction indeed to the sight of hundreds more Cheyenne and Sioux charging down upon them from the distant hills overlooking the camp. “The ground seemed to grow them,” Forsyth recalled. “They appeared to start out of the very earth. On foot and on horseback, from over the hills, out of the thickets, from the bed of the stream, from the north, south and west, along the opposite bank, and out of the long grass on every side of us.”

Making a Stand on a Nameless Island

Forsyth’s party was in danger of being wiped out in a few minutes. Their salvation was the nameless island they had seen in the river. Such as it was, the low sandy island was a natural fortification surrounded by a moat. Beecher, McCall, and Grover provided covering fire as the others made for the island. Scout John Hurst recalled, “We all made a grand rush for cover like a flock of scared quail.” Once on the island, the scouts tied their horses to bushes, forming a rough defense perimeter, and started feverishly digging rifle pits with tin plates, knives, or their bare hands.

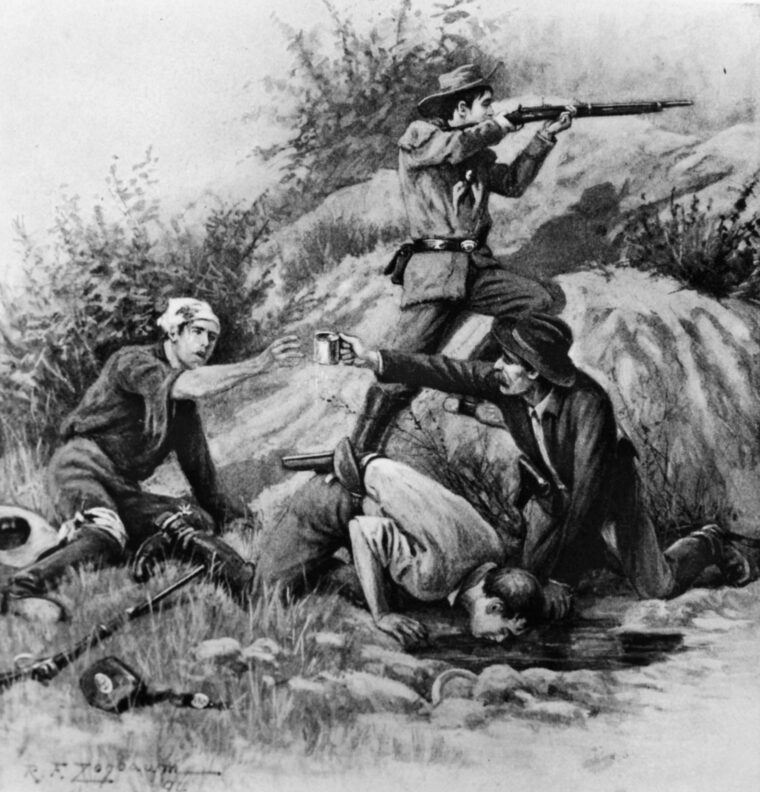

A few men, all good shots, remained hidden in thick, tall grass on the river bank opposite the tip of the island. One of them, Frank Harrington, was struck by an arrow just above his left eye socket. The arrowhead lodged tightly in his skull without breaking through to puncture his brain, and could not be pulled out. Shortly after Harrington was wounded, a mounted Indian rode near and fired a rifle almost point-blank at the scout’s head. The bullet struck the arrowhead and knocked it loose. Covered with blood, Harrington somehow managed to reach his comrades on the island. Wearing a bandage around his head like a red badge of courage, Harrington picked up his carbine and joined the others in returning the Indians’ fire.

Mounted or on foot, firing from cover, the Indians poured rifle fire into the island. Fearing that they would be shot down like dogs, some men were ready to make a run for the opposite bank. Forsyth and McCall, seeing the island as their only chance of survival, vowed to “shoot down any man who attempts to leave the island.” Beecher backed them up, shouting at the wavering men, “You addle-headed fools, have you no sense?”

Amid the incoming bullets, the scouts managed to dig enough shallow pits to allow for some cover. Forsyth stayed on his feet giving orders until a bullet smashed into his right thigh. Doctor Mooers, who had been busy with his rifle, got several men to enlarge his pit so that he could look after the major and the other wounded men. To caution a man who was firing wildly and using up precious ammunition, Forsyth raised up with his left leg. Another bullet struck him, shattering his shin.

The Last Ride of Roman Nose

The mounted warriors assembled for an all-out horseback charge to sweep over the island. Most of them were armed with lances and bows, but some had carbines or rifles of various make that they had captured in earlier clashes with the Army. When the Indians got to the tip of the island, the heavy fire from the scouts’ repeating Spencers split the massed formation in two as it passed around the island. A warrior named Bad Heart rode completely through the island amid the scouts, emerging unscathed from his bold dash. The rest of the Indians circled the island, firing into the entrenchments, and readied themselves for another charge.

Among the Indian casualties early in the battle was a Cheyenne named White Weasel Bear who was shot by one of the men hidden in the tall grass on the bank opposite the island. Weasel Bear’s nephew, White Thunder, came to look for him and was shot dead. Meanwhile, the most famous Indian leader on the scene, Roman Nose, had so far held back from the fighting. Although he was not a chief, Roman Nose’s courage, boldness, and phenomenal luck in battle had made him legendary. As a ranking Dog Soldier, he normally was foremost in any fight, but that day on the Arikaree, Roman Nose had a premonition of death. Not long before, he had eaten a meal with a metal fork, and he believed that this faux pas nullified the power of his protective talisman. Many Plains Indians avoided eating food touched by metal utensils, believing that to do so attracted metal bullets in battle.

Roman Nose decided that he had to ride into battle. There was no time for the purification rituals necessary to restore his magic, and he rode down toward the enemy, leading many riders behind him. A bullet fired by one of the scouts hidden in the tall grass along the river bank struck Roman Nose. Knocked from his horse, the stricken warrior managed to drag himself from the battlefield. Other warriors found him and bore him away, but Roman Nose died at the end of the day.

The fall of Roman Nose, the most famous Indian in the battle, became a focal point in later retellings of the fight. But at the time, the scouts may not have recognized him during the battle. Forsyth described seeing him fall, distinguished by a “magnificent war bonnet” with “two short black buffalo horns,” but Western artist George Bird Grinnell, in his talks with many Indian veterans of the battle, was told that Roman Nose never wore such a war bonnet.

The Fight For the Rifle Pits

During the mounted charges made against the rifle pits, Forsyth heard the “peculiar thud” made by a bullet that fatally struck Mooers in the forehead while he was tending to the wounded. Beecher was mortally wounded by a bullet that lodged in his spine. Although more charges followed, the Indians began to settle into a patient siege, peppering the island with gunfire from a greater distance. Concentrating their fire on the mounts tethered on the island, the Indians killed the last of the scouts’ horses by early afternoon. By dark, six of Forsyth’s men were dead or mortally wounded, and 16 others bore wounds ranging from slight to serious.

A few Cheyenne led by a warrior named Two Crows carefully made their way through the tall grass to recover the bodies of Weasel Bear and White Thunder. Three Cheyenne were wounded by scouts firing into the grass. At last the warriors reached White Thunder and went to drag his body away through the grass. Several men lying on the ground formed a line and passed along a rope that was tied around White Thunder’s ankles. With the rope, they dragged his body slowly through the grass until they were at last out of range of the scouts’ carbines.

Two Crows’ party found Weasel Bear still alive, but he told them, “I am badly wounded through the hips and cannot move.” In the same way that the dead White Thunder was dragged from the field, Weasel Bear was slowly drawn through the grass by a rope tied to his ankles. Despite the dangerous effort, he was later named as one of the Indian dead of the battle.

The scouts deepened their rifle pits and connected them with trenches. Hungarian-born scout Sigmund Schlesinger said of the long hours spent in his rifle pit: “I have often been asked whether I have killed any Indians, to which my answer must truthfully be that I don’t know. I did not consider it safe to watch the result of a shot, the Indians being all around us, shooting at anything moving above ground.” Occasionally, he jumped up for a hasty look before quickly dropping back into his hole. Working the barrel of his carbine saw-fashion through the pile of sand in front of him, Schlesinger cut a “sort of loophole through which I could see quite a distance.”

Two Scouts Leave For Help

After dark, some men slipped away to retrieve saddlebags from dead horses, seeking more ammunition or food. The little food they found would not go far among the 50 men, so others cut strips of meat from the dead horses and mules. Some of the meat was hung on the bushes to dry; the rest was buried in an attempt to preserve it. Scout Martin Burke dug deep into the bottom of his rifle pit, and shouted the good news that his well was filling with water. In their pits behind bulwarks of sand and dead, decaying horses, the scouts endured an eerie foreshadowing of World War I trench warfare.

After the fighting subsided about midnight, scouts Simpson “Jack” Stillwell and Pierre “French Pete” Trudeau slipped away from the island with a dispatch written by Major Forsyth. At 19 years of age, Stillwell was one of the youngest men in the party, while Trudeau was nearly 60 and the oldest man among Forsyth’s scouts. They carried their boots tied around their necks and started out walking backward in their stocking feet so that any footprints would resemble Indian ones. Eluding and hiding from Indians slowed them down, and they only covered about three miles before it began to get light. By daybreak, they were well hidden under a bank covered with tall grass and sunflowers. The Indians hadn’t found them, but Fort Wallace was still 110 miles away.

Stillwell and Trudeau heard firing all day as they remained under cover. Back at the Arikaree, the wounded endured a long day of anguish with their only medical officer lingering near death and their medical supplies lost in the mad rush to the island. No one knew whether Stillwell and Trudeau were dead or alive. About 10 pm, two more volunteers, Chauncey Whitney and Allison J. Piley, slipped out of camp to get help. Unable to find a way though the enemy ringing the island, they returned to the camp in a few hours.

After dark, Stillwell and Trudeau continued their journey for help. As dawn approached, they were appalled to find themselves half a mile from an Indian camp near the south fork of the Republican River. Taking cover by the river bank, they watched as Indians stopped to water their horses barely 30 feet from their hiding place, but no one saw them.

Hiding in a Buffalo Carcass

September 19, the third day Forsyth’s men spent trapped on the island, was partly cloudy and offered some relief from the sun. About noon Grover reported to Forsyth that some Indian women and children who had been watching the action were leaving. That night, Piley slipped out of camp again, this time with scout Jack Donovan. The men did not return, and the rest could only hope they got past the Indians.

As Donovan and Piley left, Stillwell and Trudeau were miles ahead. At last, certain they were past the Indian camps, they decided it would be safe to keep traveling after sunrise. But soon after dawn, they saw that they were near a Cheyenne village on the move. The best cover they could find was a buffalo carcass. Evidently killed the previous winter, the buffalo bones and the remaining hide formed enough of a tent to shield them as the Cheyenne passed by.

In finding shelter, the scouts found another enemy—a rattlesnake. Killing the rattler could well make enough noise to tip the Indians off to their presence, but the sinister rattling itself could also attract fatal attention. Stillwell evicted the snake by spitting tobacco juice into the snake’s face. With its mouth and eyes stinging from the juice, the rattlesnake slithered away and left the scouts in peace.

The fourth day of the siege found the scouts’ situation growing more desperate. Mooers died soon after sunrise, and Forsyth was in unbearable pain from the bullet in his leg. No one was willing to cut the bullet out, as it was lodged near an artery. At last, the major had two men hold his leg and he cut the bullet out himself with a razor. The almost immediate relief was cut short for Forsyth when he ordered some men to lift him up so he could survey their defenses. A fusillade of shots rang out, and one of the men holding the corner of the blanket supporting Forsyth’s broken leg dropped it and dove for cover. As Forsyth landed on the sand, a broken bone stuck out from his wound.

The remaining horse meat was rotting by this time, and the men in desperation sprinkled gunpowder on it in a futile attempt to cover the putrid smell and taste. One small event helped morale, the shooting of a small gray coyote that the men ate. The animal’s skull was boiled three times to extract every iota of possible nourishment.

In the night, Stillwell and Trudeau stepped out of their buffalo carcass. By this time, Trudeau was so sick he could barely walk. After walking all night, they pressed on during the daylight as rain mixed with light snow fell on them. Late in the morning, they stumbled onto a wagon road and soon met two Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry, who brought them to Fort Wallace. From the fort, Major Henry Cary Bankhead quickly set out with Stillwell and Trudeau, along with a relief force of infantrymen in wagons and two cannon. Word was also sent to Captain Louis Henry Carpenter, who had left the fort on patrol two days earlier with a company of the 10th Cavalry.

Carpenter’s Rescue Party Arrives

Donovan also reached Fort Wallace safely not long after Bankhead left with all the available troops. With five volunteers, Donovan headed back to the Arikaree. Piley, sick from eating the rotting horsemeat carried as their only rations, had stopped to rest before heading to the fort. He soon departed, with orders to find a cavalry detachment under Major James Sanks Brisbin to proceed to Forsyth’s relief.

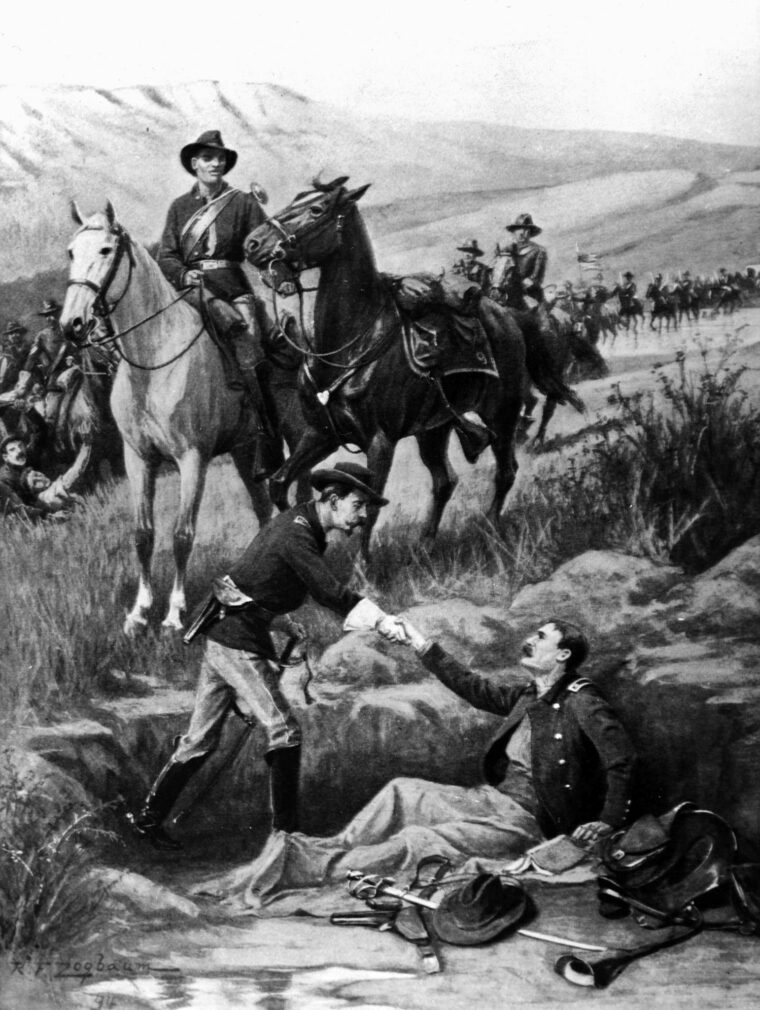

On September 23, as the trapped scouts neared starvation on the island, a party from Fort Wallace found Captain Carpenter’s company, bringing orders to relieve Forsyth, who was about 75 miles away. Two days later, nearing the Arikaree, Carpenter ran into Jack Donovan and his companions from Fort Wallace. By now, the last of the Indians had gone, although the scouts could not risk leaving the island to confirm their absence.

About 10 am, lookouts saw horsemen approaching in the distance. The cry “Indians! Indians!” alerted everyone, and several scouts ran after the foragers. Grim forebodings were instantly dispelled when a man shouted, “By the God above us, it’s an ambulance!” It was Carpenter’s rescue party. Forsyth was nearly overcome with his ordeal, but still managed to put on a show for Carpenter, a wartime comrade. Borrowing a copy of Oliver Twist that one of the men carried in his saddlebags, the major looked to be calmly reading the novel in his hospital bed dug into the sand. Seeing Carpenter, Forsyth greeted him by saying, “Welcome to Beecher’s Island.” The once nameless little sandbar in the Arikaree now had an immortal name.

The survivors eagerly devoured the bacon, hardtack, and coffee brought by the relief party. Tents were pitched some distance away, to allow the wounded to get away from the stench of the rotting horses. Bankhead arrived with more men and supplies. Assistant Surgeon J.A. Fitzgerald arrived with Carpenter and began treating the wounded. Fitzgerald had the single cottonwood tree on the island cut down. The doctor shaped the wood into a split, which he lined with cotton to protect Forsyth’s leg. The surgeon managed to save Forsyth’s legs, but the major would need two years for a complete recovery. Five men were buried on the island and another wounded scout died soon after, bringing the total number of dead to six. Nearly all of the casualties on both sides happened during the fierce opening hours of the battle, before the scouts were settled in their entrenchments.

Forsyth estimated that 35 Sioux and Cheyenne had been killed, although other accounts pushed the toll to several hundred dead. From interviews complied long afterward, George Bird Grinnell wrote that only nine Indians were killed: six Cheyenne, one Arapaho, and two Sioux. There was no reliable estimate of the number of wounded.

Exposing the Limitations of Small-Scale Expeditions

The Battle of Beecher Island was not important in a strategic sense, as it did nothing to halt Indian raids on the Great Plains. Whatever the merits of a company of skilled frontiersmen such as Forsyth’s Scouts, the battle showed that such a force was simply not large enough to make much difference in a major campaign. Harking back to the harsh lessons of the Civil War, Sheridan decided on a winter campaign to deprive the Indians of their horses, food, and shelter during the lean months of the year. Relentless attacks in the bitterly cold winter of 1868-1869, including Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s victorious attack on a Cheyenne camp at the Washita River, brought a temporary and uneasy peace to the region.

After years of pondering the issue, Congress in 1914 provided the survivors of Forsyth’s scouts, or their widows, with pensions. In their later years, survivors of Forsyth’s scouts attended reunions and led efforts to place a monument to commemorate the battle. The States of Kansas and Colorado teamed up in 1905 to establish a small battlefield park at the site, but a 1935 flood washed away Beecher Island as well as a stone monument commemorating the battle. In 1976 the location became a National Historic Site. The island itself may be gone, but the fierce battle fought there and the long, grim siege that followed created an imperishable legend that time has not effaced.

Thank you very much for this very well presented website.

I would like to purchase a color print of Roman Nose leading his

fateful charge.

I highly recommend reading George Forsyth’s own first-hand account of the Beecher Island Fight.

Daniel Woodhead