By Joan Hunt

The 13,000 ton Independence-class aircraft carrier USS Princeton, which was commissioned on February 25, 1943, quickly became known as the “Fighting Lady.” She made a name for herself supporting the occupation of Baker Island in August of that year, followed by raiding against Japanese installations on Makin and Tarawa atolls in the Gilbert Islands in September, and a busy November supporting the Bougainville landings and raiding Rabaul and Nauru and participating in the invasion of Tarawa and Makin that same month. Following a quick overhaul at the Puget Sound Naval Yard, she continued in action during the conquest of the Marshall Islands in January and February 1944.

Princeton was soon to become a casualty of the largest naval battle in history, Leyte Gulf, which was actually a series of connected naval engagements. The carrier was lost in the Sibuyan Sea at Leyte Gulf while serving under the command of Admiral William F. (Bull) Halsey. Assigned to Task Force 38.3, Princeton (CVL-23) was in company with three other carriers, USS Lexington, USS Essex, and USS Langley, along with four battleships, four light cruisers, and 17 screening destroyers.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf took place in conjunction with the U.S. invasion of the Philippines in October 1944, and a significant component of U.S. airpower that supported the landings and provided air cover for the naval vessels operating at sea was the tremendous capability of the Grumman F6F Hellcat. The Hellcat entered service in mid-1943 with six wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns, each with 400 rounds of ammunition. Some variants included a 20mm cannon with 200 rounds replacing the innermost machine gun in each wing. The Hellcat could carry up to two 1,000-pound bombs as well as six 5-inch-high velocity aircraft rockets.

Aboard the USS Princeton, it was Aviation Machinist Mate 3rd Class Frank L. Heineman’s job to keep his new F6F-5 Grumman fighter plane in the air. The F6F-5 resembled the earlier F6F-3 variant but it had extra armor, stronger main landing gear legs, and spring tabs on the ailerons for better maneuverability; most of them had water-injection engines. Both versions had a 250-gallon fuel capacity in internal tanks and a 150-gallon belly drop-tank.

Now aged 87 and living in Buena Park, California, Heineman, known to his shipmates as “Heine,” was assigned to the Princeton immediately after training, and he was aboard the Fighting Lady on the fateful day of October 24, 1944.

At daybreak, elements of the Japanese Navy were approaching the Philippines from the north and west, and Task Force 38.3 was facing a threat to the U.S. landings being conducted on the beaches of the island of Leyte. After several days of air operations that pounded enemy targets ashore in support of the Leyte invasion, the carriers launched Hellcats on combat air patrol that morning and other planes on search missions. More aircraft were on deck, ready for attack missions.

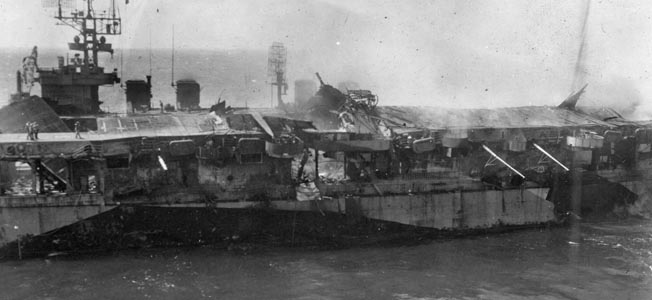

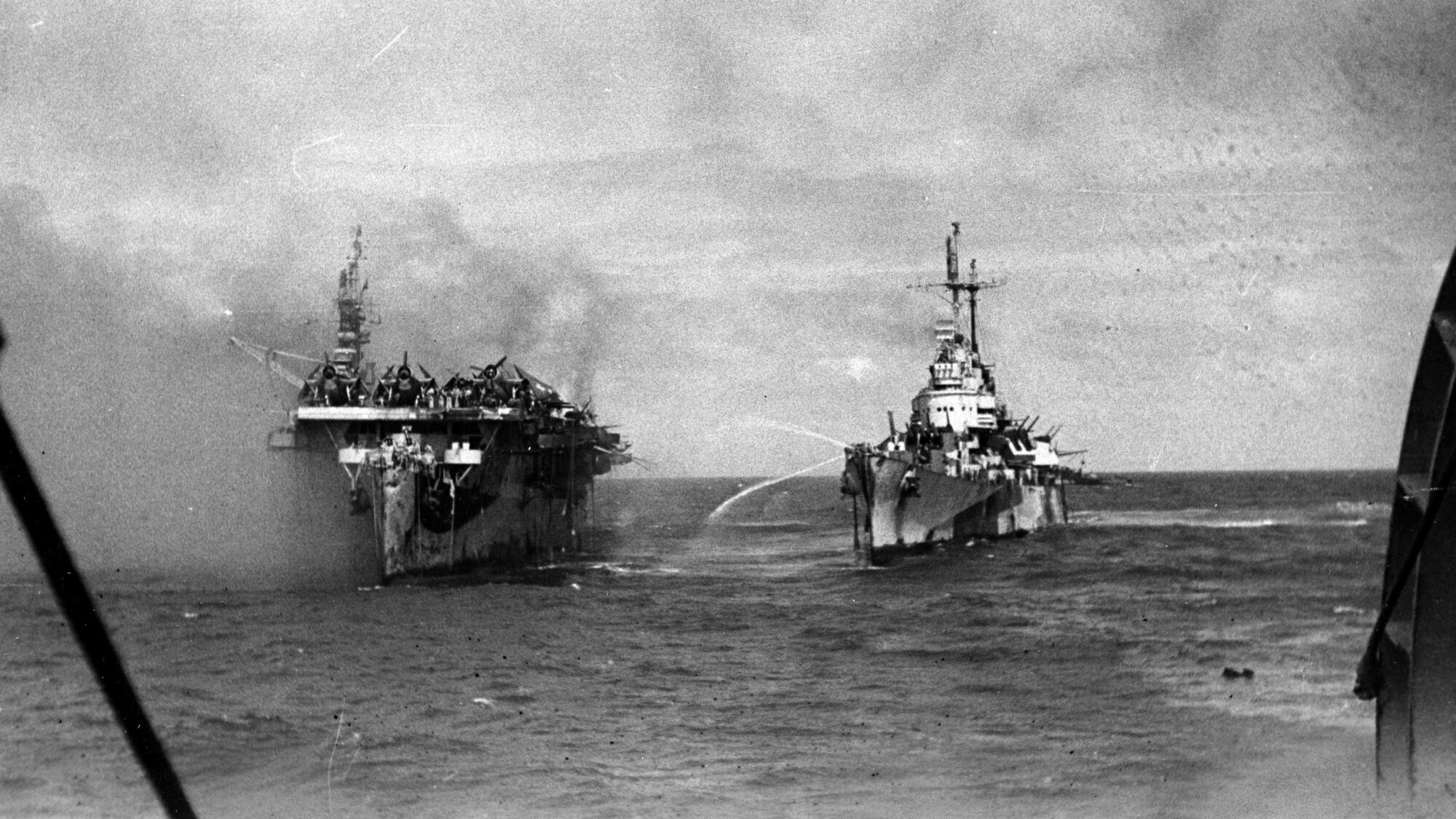

At about 10 am a lone Japanese Yokosuka D4Y “Judy” dive-bomber dropped a single bomb between the carrier’s elevators. The bomb penetrated the flight deck and hangar before exploding. The destroyer USS Irwin and the cruiser USS Birmingham came to the aid of the stricken carrier; however, sometime after 3 pm massive secondary explosions ripped through the ship and seriously damaged Birmingham. The USS Princeton was doomed.

The American Hellcat vs the Japanese Zero

Joan Hunt: What was your responsibility aboard the USS Princeton?

Frank Heineman: I had to make sure that the plane was properly fueled and ready to take off at a moment’s notice, maintaining the plane’s oxygen and fuel injection water system, seeing to it that the plane was securely lashed down when not in use. We all had to wipe off the oil slicks that accumulate during air time. They streak the fuselage undercarriage, allowing the enemy a greater chance to spot them overhead during battle. I assisted the pilot while he prepared for flight and gave him the “all clear” signal to start his engine. This was accomplished by a cartridge starter and causes the propeller to spin about four revolutions. This is enough to cause the magneto to send the necessary electricity to fire up the engine. All we had to do now was to pull the wheel chocks, and the pilot was free to go airborne.

JH: How did the F6F-5 fighter planes stack up in battle?

FH: They had a definite advantage over their enemies’ planes. The lighter Japanese Zeros were very maneuverable and on some occasions would give our pilots some trouble. Our planes were equipped with half-inch armor plate behind the pilot’s head and back. I had seen my pilot come back from a sortie with a hole in the canopy behind his head. When I inspected the inside of the fuselage, there was a large indentation in the armor plate behind his head. This is the kind of hit that would have killed my pilot had he been piloting a Japanese plane, as they didn’t have the armor or self-sealing fuel tanks needed to bring the fighter planes back to a safe landing aboard their carriers.

The American pilots had a decided advantage in combat as their Pratt & Whitney engines were equipped with a water fuel injection system, which, when called upon during the heat of battle, would give them a chance to outrun, outmaneuver, and possibly finish off the enemy.

The “Mariana’s Turkey Shoot”

JH: How had the USS Princeton performed since you were transferred aboard in spring

of 1944?

FH: She had already accumulated seven battle stars and was now ready to acquire more by attacking Japanese targets in the Central Pacific. We continued on supporting amphibious landings at Hollandia, New Guinea. In June, the Princeton participated in the invasion of Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Rota, all of these islands making up the Mariana chain. This was quite a campaign, loaded with enemy action. Our planes really had a field day, as our whole carrier group shot down about 400 enemy aircraft. That also included the amount hit by gunfire from our ships that were under attack. This incident is what created the name the “Mariana’s Turkey Shoot,” as representing what had happed that day.

JH: How did the USS Princeton’s planes fare in this engagement?

FH: Darkness was fast approaching, and our aircraft were on their way back to the fleet. As they were nearing their destination, realizing they were low on fuel and nightfall was closing in fast, it became apparent to the admiral some drastic action would have to be taken. After giving it some thought, knowing that his decision would put the fleet at the risk of a Japanese submarine attack, he ordered all carrier captains to light up their flight decks and prepare for night landings.

The incoming planes, low on fuel, pilots tired from a day-long battle with hundreds of Japanese aircraft of all types, were left very little room for error. Most of them would have to come aboard on the first attempt, no wave-off or trying another landing. Our carrier was very lucky, as we retrieved our squadron without a mishap, although we did have to wave off a Japanese Zero trying to come aboard without an arrestor hook to bring him safely to a halt. Never saw him again.

Abandoning the Princeton

JH: Where were you when the bomb hit the USS Princeton that morning?

FH: Having sent our fighter planes off about 0600 hours with the mission of attacking the Luzon airfields in support of General Douglas MacArthur’s landing troops, the planes began returning about 0900 hours, and I had just secured my F6F-5 Grumman aircraft. I had checked it over thoroughly for any problems and found the oxygen tank needing a replacement. After securing a new one in place, I crawled out of the fuselage and was securing the hatch when all hell cut loose. I got up just in time to hear ack-ack fire from the Marine gunners on the forward 40mm gun mount.

I can still visualize the large white hub of his [the Japanese pilot] propeller, not more than 100 feet above me, as he released his lethal bomb that hit amidships between the forward and after elevators. It penetrated the flight deck, producing a 15-inch hole, then continued on down through the hangar deck and into the galley area, where it exploded, killing cooks, bakers, and other crewmen in the vicinity of the blast. The flames shot up through the holes it had created, setting the hangar deck on fire.

JH: What was the immediate result of the strike?

FH: While the firefighting crew was busy on the flight deck trying to extinguish the flames with an inadequate water supply due to damage suffered below, the hangar deck containing 10 TBM Avenger Torpedo bombers being prepared for another strike at the enemy was all ablaze with 100-octane high-test fuel as its source. The bomb, when it exploded, produced so heavy a concussion that our TBMs dropped their extra fuel tanks to the deck; they burst open upon impact and spilled the fuel in all directions. The firefighters could not contain this fire, which had quickly spread throughout the hangar deck with hungry flames making their way to the torpedoes secured in the bomb bays of the TBMs.

JH: What did you do next?

FH: As the fire continued unabated, those of us located topside tried to render assistance as much as we could. We experienced the effect of several torpedoes blowing up on the hangar deck. The blasts, at regular intervals, would lift us about six inches above the flight deck. The captain announced over our loudspeakers so all could hear the order “abandon ship, abandon ship!” This is an order a sailor never wants to hear.

JH: Were there lifeboats, or did you just jump overboard?

FH: I had a young crewman under my guidance, as he was working to be a plane captain. He was very eager to be one and showed good promise, when tested. His name was James (Jimmie) Jarrell from Louisville, Kentucky. Here we are on the forward flight deck and about 400 feet from our gear locker, as the fire was out of control and preventing us from retrieving our life jackets. We recovered a life raft from my plane’s cockpit. As Jimmie was just learning to swim, I thought it would be a good idea if he lowered himself in the water via the line thrown over the side for that purpose. I dropped the inflated life raft to him and said I would join him shortly. Problem was, when I hit the water there was no Jimmie sitting in the life raft waiting for me. I swam around looking in all directions for a sign of him or the raft. That is the last I saw of a really fine young man, full of vim and vigor.

JH: How did you survive without a life raft?

FH: After swimming for a couple of hours, I came upon a 5-inch powder bag can that was occupied by a sailor who was a cook. There was enough buoyancy that it was capable of supporting us both until we were pulled out of the water by the [destroyer] USS Morrison.

JH: Where was the USS Morrison headed?

“The Whole Aft of the Princeton Blew Sky High”

FH: Now that the Japanese aircraft were no longer coming at us, the Morrison pulled up along the port side of the Princeton, which by this time had developed a 10-degree list to port. As we arrived we were greeted by a bunch of debris and two plane tractors coming off the flight deck. Fortunately, no one was hit, but then our ship’s radar antennas managed to interlock with the Princeton’s antennas. When we finally broke away from her grasp, the Morrison’s ability to use our radar system to aim and fire our 5-inch guns was nullified.

JH: Were other ships giving aid to try and save the USS Princeton?

FH: The light cruiser USS Birmingham was on the starboard side of the ship, doing her best to help put her fire out. Everybody had turned to getting the fire under control, when the admiral gave orders to all ships in the area to break off aid to the Princeton and get under way, as Japanese aircraft had been sighted and were heading our way. Our patrolling Hellcats engaged in dogfights with them and soon the USS Birmingham, the [cruiser]Reno, and the [destroyer] Ward returned after being away for a couple of hours. Upon their return, they were greeted by a severe fire [aboard the Princeton] burning out of control.

JH: With so much fuel and munitions aboard the Princeton, wasn’t it risky being near her in the water?

FH: As it turns out, it was. The USS Morrison with myself and our surviving crew was off at a distance cruising about observing the ever-increasing flame and smoke on board the Princeton, noting that the USS Birmingham was the only ship spraying water on it, when all of a sudden there was a terrific explosion on the fantail. The whole aft end of the Princeton blew sky high, showering the Birmingham with an endless amount of deadly shrapnel. In an instant, this explosion killed and wounded 600 men on the Birmingham and the Princeton.

JH: What did you see from your vantage point on the Morrison?

FH: [It was] a horrific scene of the worst kind, crewmen helping the injured and dying as they lost their footing because of the blood-covered decks, ladders, and passageways. They quickly poured sand all around in order to regain traction of their deck shoes. Now aboard the Princeton, our new captain, John Hoskins, lost a foot, as Captain William H. Buracker rendered aid to stop the bleeding. Commander Roland Sala, our senior medical officer, although injured, administered morphine and sulfa powder, using a sheath knife to cut off part of the leg that was dangling. Shortly after, Dr. Sala himself had to be given treatment for his wounds. All the ships that were helping out and near the Princeton were ordered to pull away and get a good distance, as there was no chance to save her and we were going to sink her.

Sinking the Princeton

JH: How was the Princeton sunk?

FH: The light cruiser USS Reno was given the order to take over and finish off the USS Princeton [after near misses by the USS Irwin, whose launching tubes had been damaged]. The Reno launched two torpedoes at her hull broadside, and they both struck her around the magazine area. The explosion was so violent that it sent up a column of smoke, topping out at 1,500 feet. When the smoke cleared, the Fighting Lady, as she was known, had disappeared beneath the ocean waves, finding a new home some 20,000 feet down, taking with her the nine battle stars she so valiantly fought for and earned, as costly as it was.

JH: Where did you and the other survivors go?

FH: All of us survivors ended up at Ulithi, our farthest supply base in the north Pacific. Here we were issued the much-needed and required clothing, gear, and necessities to sustain us. We were put aboard a troop transport and got under way for a long trip home. We ended up in San Diego, California, while they worked on our records and getting the right paperwork finished so that we could go on our survivors leave and return for our next tour of duty.

JH: How many perished aboard the USS Princeton?

FH: One hundred and fifteen lives were lost.

JH: What was the result of the action at Leyte?

FH: The Third and Seventh Fleets had wrecked the Imperial Japanese Navy. We finished off four aircraft carriers, three battleships, 10 cruisers, and nine destroyers, damaging many more. The battle for Leyte Gulf was an overwhelming triumph for the U.S. Navy against the losses.

Aftermath of the Battle of Leyte Gulf

The United States lost the light carrier Princeton, two escort carriers—the USS Saint Lo and USS Gambier Bay, two destroyers—the USS Johnston and USS Hoel, and one destroyer escort—the USS Samuel B. Roberts and a few lesser craft (these in the battle off Samar on October 25).

The Battle of Leyte Gulf left the U.S. Navy in command of the eastern approaches to the Philippines, providing support for General MacArthur’s invading forces and maintaining the seaborne supply lines pouring men and munitions into the combat area.

Two months after Heineman’s experience at Leyte Gulf, he escorted Priscilla, his sweetheart from Lakeview High School, down the aisle. Stationed later at Brown Field in California and living in Chula Vista, he repaired the same type of airplanes that were aboard the Princeton, and the following year the Heinemans’ first child was born, “a real beauty, a blond baby girl, we named Diana Lynn,” he said. He was discharged from the service on December 7, 1945, Pearl Harbor Day.

Heineman refers to his loving wife of 65 years—mother of two daughters, grandmother of five, and great grandmother of five—who passed away in April 2009, as “missing in action.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments