By Stephen D. Lutz

Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain consists of 69 measurable islands. Just as many more exist, too small to measure as an island. For Japan in World War II, they made the perfect island-hopping path toward America’s West Coast, and apparently that was Japan’s intent in capturing two of those islands in June 1942. They held residency on Attu and Kiska for 14 months.

What stymied Japanese success in the Aleutian campaign were the sea battle of Midway, June 4-7, 1942, then the prolonged ordeal of Guadalcanal, August 7, 1942-February 9, 1943. These two battlefronts overshadowed occurrences along the boundary separating the North Pacific from the Bering Sea. Many believe Japan’s thrust into Alaska’s extended island chain was a diversion connected to Midway. A deeper analysis shows a more complicated desire to lay claim to that sea highway leading to America’s West Coast.

Purchased from the Russians by Secretary of State William H. Seward in 1867, Alaska was long seen as a frozen, forbidding outpost with little value, military or otherwise. In the era before statehood in 1959, Alaska was officially a United States territory.

The Aleutians are barren, volcanic rock islands nearly void of any vegetation or human population. From the southwest tip of Alaska, they stretch 1,200 miles west, arching toward Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. West to east, the islands of importance are Attu and Kiska. Closer to mainland Alaska are Amchitka, Adak, Umnak, and Unalaska, with its port of Dutch Harbor.

America had been slow beefing up its farthest northern border defenses including Dutch Harbor. In 1923, Dutch Harbor was merely a 23-acre coal station catering to shipping from Russia and North America across the Bering Sea. By January 1941, it became a full-scale, functioning naval station. On May 8, 1941, the U.S. Army made Fort Mears home for its 7th Infantry Division. The Navy-Marine populace numbered 640; the GIs added another 5,425.

Dutch Harbor came to host a 5,000-foot runway, 200-bed hospital, water processing plant, an aerologic station for atmospheric reporting, and a set of 6,666-barrel fuel-oil tanks. The Navy’s air wing accounted for eight radar-equipped Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats.

In due time the Army established an air base at Fort Randall at Dutch Harbor, starting with six medium bombers and 16 fighters. Newer strips would come later at Fort Glenn on Umnak, with one heavy bomber, six medium bombers, and 17 fighters. As events heated up, those numbers increased as two air groups of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s 111th Fighter Squadron arrived. Mixing with their American counterparts, they became the 343rd Fighter Group.

Dutch Harbor was no Pacific pleasure post. At some points in the Aleutians, craggy mountain ridges reach 4,000 feet. They are littered with gullies, ridges, and rocky outcrops. Caves created by ancient volcanic activity exist in abundance. The only predictable weather pattern is its unpredictability. Rain, drizzle, snow, and hurricane-force winds dominate the environment. Rain can measure up to 50 inches or more per year, while winter snow piles up deeper than 10 feet.

At any given time, five out of seven days are miserable at best, with fog thick enough to be blinding. Ships can pass one another within a few hundred yards in the fog and not see one another. The terrain is largely frozen or partially thawing tundra muskeg.

Why would any army or navy want to fight for such a forsaken, inhospitable landscape? The military significance to Japan was that aircraft based on the farthest western island lay within range of Japan’s Kurile Islands. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had developed bases in those islands for reaching across the North Pacific. Aircraft based in the Aleutians could also reach Japanese-held Kamchatka Peninsula, another vital launching point for North Pacific naval activities.

The need to occupy or neutralize any threat from the Aleutians became apparent on April 18, 1942, when Colonel James Doolittle’s 16 North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers struck Tokyo from an unknown locale. The strike drove Japan’s high command mad trying to determine their point of origin. One of the leading suspected sites was the Aleutians––in particular the island of Attu. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, saw even more reason for conquering those islands.

Having once lived in America, Japan’s most respected admiral knew facets of American life his superiors did not comprehend until too late. Yamamoto believed that war with America would lead to disaster for Japan. America, he knew, could go far beyond manufacturing just cars and refrigerators. Once America was pushed into war, Yamamoto saw only one way for Japan to win: destroy America’s industrial and manufacturing infrastructure long before it could convert to war production. Yamamoto’s solution was to take out America’s “Pacific Ocean Triangle Defense System.”

The three points of this imagined triangle—the Panama Canal, Pearl Harbor, and Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians—formed America’s Pacific Ocean defense perimeter. Whatever America produced on the East Coast traveled via the Panama Canal to the West Coast, and the West Coast fed Pearl Harbor and other U.S. bases in the Pacific.

Yamamoto’s premise for the attack on Pearl Harbor was to eliminate America’s Pacific Fleet and lay open the width and breadth of the Pacific Ocean for Japan’s navy. From there an advance upon the Aleutians could be made. On the West Coast, areas such as Seattle and Southern California, where most of America’s aircraft-manufacturing plants were located, would be vulnerable. Then, in due time, the Panama Canal would be neutralized. With those three points under Japanese control, America would be on the verge of collapse.

Many Japanese leaders also believed that a renewal of hostilities with the Soviet Union was inevitable. The capture of Attu and Kiska might impede the delivery of any Lend-Lease matériel from the United States to the Soviets. By the late summer of 1942, the first of 8,000 U.S.-built aircraft were being flown to the Soviet Union from Dutch Harbor.

Yamamoto’s Aleutian thrust has been described as a diversionary tactic to lure American naval forces away from Midway; however, some historians debate this assumption and point to the reasons that the Aleutians would have been a primary target. Yamamoto sent 34 ships north, creating the Northern Area Fleet under Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya. He assigned two small aircraft carriers, Junyo and Ryujo, to the Aleutian operation.

Yamamoto added in five cruisers, 12 destroyers, six submarines, four troop transports, and various auxiliary supporting vessels. It could be argued that the absence of these ships made the difference at Midway. Those few ships, in particular the two carriers, could have turned the tide of battle at Midway.

While the bulk of American naval forces confronted the Japanese at Midway, Task Force 8 under Rear Admiral Robert A. “Fuzzy” Theobald moved toward the Aleutians with two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and four destroyers. Hosogaya sailed north expecting far more resistance then he found.

Dutch Harbor was on high alert. Since mid-May, Army personnel had been rising by 4:30 amto man their weapons: two eight-inch coastal artillery guns, two 90mm antiaircraft gun emplacements, one three-inch antiaircraft site, and four 155mm howitzers.

On June 2, 1942, a Navy PBY located Hosogaya’s fleet 800 miles southwest of Dutch Harbor. The Japanese fleet then disappeared in the inclement weather and shrouding fog. By 4 amon June 3, Hosogaya was 180 miles southwest of Unalaska and Dutch Harbor.

The Ryujo launched 11 bombers and six fighters; one bomber plunged into the water at takeoff. Junyo sent off 15 bombers and 13 fighters, all for naught. The weather became so foul it obscured the pilots’ visibility. The Japanese pilots from Junyo abandoned their quest and returned to the carrier.

Expecting the Japanese, Dutch Harbor picked up the in-bound flight from Ryujo before it arrived. There was enough time for ships to cut loose and head for open sea but not enough time to clear the harbor entirely. By 6 am, 14 bombs had been dropped on Fort Mears, destroying two wooden barracks and three Quonset huts.

But the attackers were thrown for a loop when a thick curtain of antiaircraft fire rose up at them; they had not expected such a coordinated defense. The Japanese pilots hurried over other selected targets, missing them. Some bombs splashed into the water. One attacker was shot down and a second attacker was visibly damaged but flew on.

A second attack achieved nothing, but a third wave of three planes claimed credit for taking out Dutch Harbor’s radio station and damaging a stationary barrack ship, the USS Northwestern. One antiaircraft gun was taken out with the loss of two soldiers.

By the time Fort Randall, some 200 miles distant, got word of the attack and scrambled a flight of Curtiss P-40 fighters, the attackers had long departed.

At 9 am, Hosogaya formed a final air assault. This time it targeted five destroyers exposed side by side at anchor. That proved unproductive as well. By the time the planes arrived within sight of their goal, low-hanging fog settled in, obscuring the destroyers from view.

In the final count, 50 Americans were killed on the ground with just as many wounded. The attackers lost two fighters, one medium bomber, and one floatplane. The Army’s 1Eleventh Air Force lost two fighters and one medium and one heavy bomber. That was the extent of war visited upon Dutch Harbor. Hosogaya’s fleet escaped undetected under a blanket of fog. Attention for the upcoming year would focus on the islands Attu and Kiska.

Off Attu on June 7, 1942, Hosogaya put Rear Admiral Sentaro Omori in charge of one cruiser, two destroyers, one transport, and one minelayer. Leading the charge ashore was Major Matsutoshi Hozumi, who spoke excellent English and kept his 1,200 soldiers in strict military order. The Japanese invaders found little resistance with Attu having barely 50 residents centered on the village of Chichagof––45 or so were native Aleuts.

The two American residents were the married couple Foster C. Jones and his wife Etta. Foster worked for the U.S. Weather Bureau while Etta, a nurse turned schoolteacher, taught there. The Aleuts were rounded up. One woman was wounded in the foot by a bullet, and one Japanese soldier was accidentally wounded by a comrade.

At first the Japanese conquerors played nice. They attempted to play with the children and tried fishing with the adults. But soon Etta Jones and the Aleuts were packed off to Yokohama and detention until war’s end. Etta survived to return, but 16 Aleuts would not. Foster Jones died by means and whereabouts unknown. It has been assumed he was shot evading capture and his body never recovered. With all that drama, Japan conquered Attu to hold it for the next year.

At 1:15 on the morning of June 7, 1942, about 480 miles southeast of Attu, 500 Japanese Marines of the Maizuru Third Special Land Force crept ashore on Kiska. Kiska was of greater importance due to its deeper harbor and potential for an improved air strip.

Captain Tekeji Ono led his Marines up to a three-shack, U.S. Navy-operated weather station. Expecting the enemy arrival, the 10 American sailors burned as many documents and destroyed much equipment as they could before fleeing the premises. Within two days, nine were caught. They also were forced to abandon their mascot, a dog named Explosion.

For 50 days, the missing sailor, William C. House, remained at large, hiding in a cave and living on a diet of moss, grass, worms, and insects until he had lost so much weight he was forced to surrender or starve to death.

The treatment of the American prisoners was acceptable until they were shipped off to Japan for internment in labor camps. All 10 survived the war to come home.

In no time, 1,000 more Japanese were ashore at Attu, while three times that number occupied Kiska. A fair share were engineers and construction workers, proving Japan had long-term plans.

By June 11, 1942, the Americans at Dutch Harbor realized they had not heard from their 10-man weather team on Kiska. A Navy PBY flew over Kiska and confirmed that the enemy was in control.

By the end of July, the Japanese were working on various installations. Even those of the 301st and 302nd Infantry Battalions became worker ants––whether heavy machinery was available or not. Complex underground bunkers were tunneled out. Underground machine shops were put in. A launch site for three mini-subs was readied for use. Barracks, below and above ground, were put into operation, and a hospital was established. One doctor there, Nebsi Tatsuqochi, had received his medical education and license in California in 1938.

Nothing was more important than the airstrip, and work continued on that almost around the clock. Japanese engineers faced never-ending challenges working in the mucky tundra, too soggy to handle aircraft. Japanese seaplanes were moored in the harbor.

As work progressed, Hosogaya renamed Kiska “IJN 51st Naval Base.” But then the admiral was dealt a devastating blow. After the Midway debacle in which Japan lost four carriers, two heavy cruisers, and 332 planes, Yamamoto wanted to recoup as many carriers and planes as possible for another day’s sea battle. Prior to returning to Japan, Yamamoto called back Hosogaya’s two carriers, Ryujo and Junyo.

For a while, the Japanese occupying Attu and Kiska received supplies via surface ships, but in time too many became targets. Submarines took their place for resupply operations. Never knowing how vulnerable their Navy code had become, the Japanese submarines also became easy targets. Life on Attu and Kiska quickly became deadly for the Japanese.

The U.S. Navy’s first response to the invasions came via their fleet of PBYs. Serviced by the tender USS Gillis, the PBYs were armed with bombs. This became necessary because of the planes’ long-range flying capabilities. The PBY pilots flew nonstop on 20-hour missions until the Gillis could no longer provide fuel and bombs.

For their part, the U.S. Army’s first attempts at bombing proved less than successful. The Army’s first flight consisted of B-24 Liberators over Attu at 15,000 feet. As one B-24 opened its bomb bay doors, a Japanese 75mm antiaircraft round found the open door, ignited the plane’s bomb load, and literally blew the bomber in two. So much shrapnel flew that two adjoining B-24s were damaged.

A B-17 Flying Fortress raid targeted anchored ships in the bay. Not a single ship was hit.

By late October, the U.S. Eleventh Air Force took to bombing both islands daily as weather permitted. Among the ordnance dropped were improvised incendiary bombs––rubber bags full of gasoline. Other innovations came with bombs made of empty glass bottles, their shards becoming shrapnel.

In March 1943, America got serious about retaking Attu and Kiska, the main target being the latter’s still unfinished airstrip. The U.S. Navy kept an ever-tightening noose around Attu, instilling fear in the hearts of inbound Japanese sailors trying to land relief supplies ashore. As Japanese surface ships begged off, the hopes went more and more to the I-Series submarines. While the U.S. Navy kept track of their coming and going, Japanese submarine losses mounted.

On March 9, 1943, in heavy fog, the last sizable Japanese surface resupply ship reached Attu. A month later, one sub did get through with a special passenger: Colonel Yasugo Yamasaki. He was saddled with the unenviable task of commanding the deteriorating state of affairs on Attu. His wisest move was to consolidate his remaining 2,600 solders on the high ground above Massacre and Holtz Valleys.

Later that month an American command prepared for a large amphibious landing, targeting the 35-by-20-mile island of Attu. The assault was assigned to the 15,000-man 7th Infantry Division.

March was a big month for the U.S. Navy as well. On the 26th, a U.S. task force led by the heavy cruiser Salt Lake City stumbled upon a Japanese relief convoy bound for the Aleutians. In a rare classic naval shootout between surface ships, the outnumbered U.S. warships turned away Japan’s last-ditch surface attempt to reach its distant outpost. This battle became known as the Battle of the Komandorski Islands. Although Hosogaya’s force was on the verge of victory, the admiral, fearing American warplanes would soon be arriving, broke off contact and sailed for home waters.

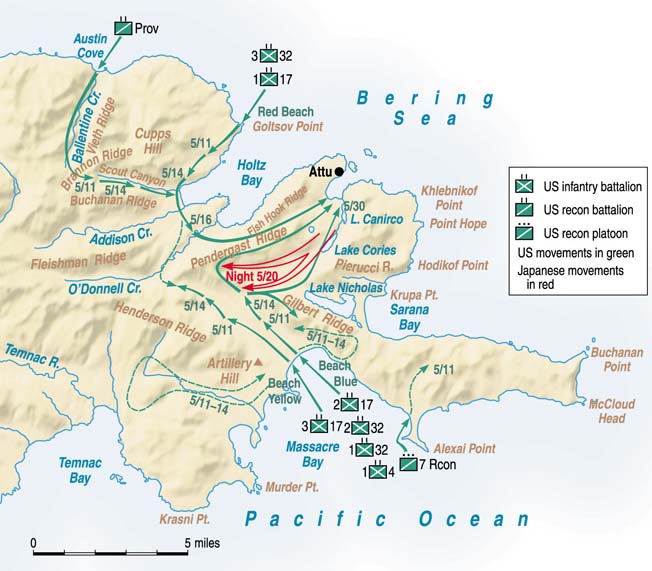

The U.S. Army’s plan to retake Attu was a classic pincer movement to be implemented May 4, 1943. There was a one-week delay due to customary foul weather but on May 11 the American force departed from Cold Bay, nearly 1,000 miles east of Attu.

A strike force of 210 scouts from the 7th Division, led by Captain William H. Wiloughby, came off the U.S. submarines Narwhal and Nautilus before daylight on the 11th. Landing north of Holtz Bay, the ground troops proceeded northeast. Expecting a short stay, each man carried only two days’ rations.

The main force of 15,000 men landed at Massacre Bay shortly after the scouts came ashore, with the battleships Pennsylvania, Idaho, and Nevada providing fire support; none of the ground troops met significant resistance. Yamasaki had removed his garrison to higher ground above the two-mile-long Massacre Valley, a movement achieved with the aid of fog shrouding the relocation.

Conquering Attu proved far more challenging than expected. It would take five days for the Americans to clear the valley. The terrain was so difficult that supplies had to be carried in on foot since no vehicle could maneuver across the soft ground. While daylight temperatures hit a balmy 45 degrees, at night they dipped to below freezing, and the 7th found itself slogging through either water-soaked or frozen ground. Unfortunately, the GIs wore standard issue leather boots not conducive to cold, wet operations. Weather-related injuries––water-soaked foot emersion and frostbite––took a greater toll than enemy gunfire.

On the other side, Yamasaki resigned himself to his fate; neither his air force nor navy were coming to save him. The U.S. Eleventh Air Force dominated the sky, with the Japanese having nothing to match them.

For over two weeks the cat-and-mouse game continued across the higher ground of Attu. By then Yamasaki found himself cornered in the Chichagof Valley with no way out. The Japanese determination to fight or die had been seen by the GIs; only two prisoners were taken up to that point. The message was clear: Yamasaki’s command would never willingly surrender.

On May 15, after the Japanese holding a ridge overlooking the bay slipped away, American troops were moving to occupy the position when U.S. fighter pilots, seeing movement down below and thinking it was the enemy, accidentally bombed and strafed them. Then, once the battered American infantry reached the top, a platoon of Japanese rushed them, only to be slaughtered.

The top brass became unhappy with the 7th Infantry Division’s slow progress, and Maj. Gen. Albert Brown was relieved of command; Maj. Gen. Eugene Landrum was installed in his place. Landrum immediately threw in the 14th Infantry Regiment to boost the drive onward.

The end of Attu’s fighting came on May 29, 1943, when Yamasaki personally led 800 followers in a banzai charge. That was only after they killed 600 of their own who were ill or injured and could not participate in the charge. Some of the wounded Japanese soldiers killed themselves.

Yamasaki’s maddened wave of blood lust carried farther than he thought it would. Although he died leading his troops, his rush reached Fishhook and Buffalo Ridges and plunged into the rear echelon of the 7th Division. There the invaders rushed a tented field hospital, killing scores of patients confined to beds.

Only by rousting cooks, medics, clerks, and engineers did the Americans stem the tidal wave of death. The final body count was 2,600 Japanese killed in action (or murdered by their comrades); only 29 were collected as prisoners. For the Americans, 549 were killed in action, with 3,200 wounded or injured by weather exposure. By June 8, 1943, American planes were flying from the airstrip on Attu.

Taking Attu was tough, and Kiska was known to have possibly three times the enemy force seen on Attu. What would it take to reclaim Kiska?

By American estimates, Kiska could have no fewer than 8,000 enemy soldiers upon it, so the U.S. Eleventh Air Force, aided by Canadian airmen, kept pushing attacks upon Kiska to soften the defenses. Admiral Theobald made a mid-July 1942 decision to give Kiska one massive shellacking by naval bombardment. But when attempting to do so on July 18, fog rolled in so thick that his gunners could not fire accurately. Four of his nine destroyers collided with one another. Theobold called off the bombardment and withdrew his ships.

On August 3, 1943, it was a man-made fog that got in the way of Allied planes. Japanese defenders on Kiska placed such a large concentration of antiaircraft weaponry in such a confined space that smoke covered the intended targets, causing the air attack to be called off. Then came developments from the other end of the Pacific: Guadalcanal was grabbing news coverage and badly needed supplies. The Aleutians ordeal had to be settled promptly.

During the summer of 1943, the Eleventh Air Force hit Kiska daily whenever the weather allowed. American bombers dropped 3,000 bombs on Kiska on August 4. The U.S. Navy took up its own schedule of shelling with battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. By then an Allied plan code-named “Cottage” was finalized, dictating the assault on Kiska. Much of the plan came from the lessons learned from Attu’s mistakes. A landing force twice the size of the one that hit Attu, reached nearly 35,000.

Back in Japan, the warlords were giving up on conquering the Aleutians. For them, the 5,000 men in the Aleutians would be better utilized and have a more significant impact in other locales across the Pacific. It was imperative to extract their soldiers from Kiska rather than see them wasted as on Attu. In so doing, a plan was put together to send 11 destroyers into Kiska Bay and out again, evacuating the entire garrison. That would be a magical feat considering the tight Allied grip around Kiska. Incredibly, that magic was there when needed.

On July 28, 1943, at about noon, nine Japanese destroyers entered Kiska Bay under the shroud of fog they had hoped for. That fog caused two of the ships to collide and resulted in their being removed from the evacuation process, but the rest of the ships carried on.

Personal weapons and lightweight crew-served weapons were thrown into the bay before boarding. All 5,300 Japanese solders were sequestered aboard the seven destroyers and evacuated from the hell that Kiska had become. All they had to do was get through the U.S. Navy net surrounding Kiska.

Luckily for the Japanese, at that moment there was no net around the island. A U.S. Navy ship picked up a radar ping identifying a distant target. Then a second honed in on the same sound. A third picked up on the pip of a radar reverberation. At that time the entire fleet surrounding Kiska sailed in the direction of the pips, thinking they had located the inbound Japanese rescue fleet.

The fog remained so thick, the U.S. Navy gunners had no idea what they would be shooting at, but they started shooting anyway. Their target was a weather anomaly bouncing back the radar emissions. The great shootout became known as the Battle of the Pips. While that was taking place, 5,300 Japanese soldiers got off Kiska unchallenged. Flyovers from July 29-August 14 showed no signs of life on Kiska, but nobody knew whether the Japanese had left or were hiding.

On August 14, 1943, some 35,000 Canadian and American soldiers stormed Kiska. This force included 15,000 from the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division, 5,000 from the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 10th Mountain Division, 5,300 from Canada’s 13th Infantry Brigade, and 2,000 from the combined Canadian-American 1st Special Service Force.

The ground troops were not sure what they would find. They did discover one survivor, the dog Explosion, the abandoned mascot of the 10-man Navy weather station. The Japanese kept Explosion as their pet but ultimately left the dog behind.

The Japanese also left behind a collection of booby traps. Before declaring the island free of the enemy, 99 men would die––24 from friendly fire by their comrades mainly due to the heavy fog. Fifty more were wounded in the same manner, and four were killed by booby traps. The highest number of fatalities occurred when the American destroyer USS Abner Read hit a Japanese mine; 71 sailors died.

Before war’s end, the entire Aleutian chain returned to American control. From those far-flung islands, American bombers were able to reach the Japanese Kurile Islands. The threat to America’s West Coast from the north had evaporated.

Good article, but the Kamchatka Peninsula was always part of Russia/USSR and was certainly not held by the Japanese at any time.

Thank you for this article. The battles @ attu & kiska are always lost in the coverage of midway. The story of the explosion of the mascot dog was interesting. I was afraid the Japanese might have eaten him!

.

In 1976, I was assigned to a Signal Battlion in Germany. One day one of our supply sergeants came through my office. I asked him why he had an Air Force patch on his right shoulder. He stated that during World War II, he had been assigned as the weather officer on Dutch Harbor. He had graduated from college (can’t remember which one) with a degree in meteorology. After the war he attended the University of Missouri, where one of his drama classmates was George C. Scott. After a short unsuccessful theater career he inlisted in the Army in 1956. Quite the character, he requested an unusaul request for redeployment travel when his tour ended with my unit. He travelled via military flights from Frankfurt to Bangkok (to visit his cattle ranch) to Manila (to visit his copa plantation) to Honolulu (to visit his pineapple farm) to his new station at Fort Bliss.

The Aleutian campaign was clearly illustrative of the term “fog of war.” Because of the weather, the entire operation could have gone either way for the combatants.

You state that 300,000 bombs were dropped in one day which can’t be correct. You also allude to the battle of Guadalcanal as causing supply problems in August of 1943, that island was totally secured six months prior.

Thanks, an avid reader of WW ll

Great Article! I would dearly love to see a picture of Explosion the Mascot? I wonder if such a pic exists?That is a great story that he survived…..