By Phil Zimmer

The P-39 Airacobra was a bit like Rodney Dangerfield—it “couldn’t get no respect,” especially from those who never piloted the “Flying Cannon” built by the Buffalo, New York-based Bell Aircraft Corp.

But those who flew the P-39 came to love it and its idiosyncrasies. When flown properly, the plane—built around its fearsome 37mm nose-centered cannon—could knock anything out of the sky, cause calloused, flak-tossing antiaircraft crews to scamper for the ditches, and reign havoc over fortified enemy command and control positions with its four .50-caliber machine guns blazing away in later versions of the craft.

At the same time, the plane was considered underpowered with its 1,200 horsepower Allison V-1710 engine, although it could do 376 miles per hour at 15,000 feet. Also, it lacked a supercharger that limited its effectiveness above 17,000 feet. Worse, the P-39 had a reputation for tumbling out of control when operated by inexperienced pilots.

“Nothing could touch a P-39 used below 15,000-feet” contended American Air Ace Lt. Col. William A. Shomo who flew P-39s, P-40s, F-6Ds, and a P-51D in WWII. He wouldn’t have hesitated to have even taken on the vaunted P-38 at lower altitudes because of the extreme maneuverability of the “Flying Cannon.” And it could tangle successfully with a Japanese Zero, he argued, if the American pilot kept his airspeed at 300 miles per hour or better so the enemy “couldn’t turn inside you.”

The Americans in the field experimented with the aircraft throughout the war to continually gain an edge and some additional speed, eventually stripping off a chunk of belly armor under the seat that weighed some 750 pounds. With those modifications, the P-39 could “fly like a bumble bee,” asserted Shomo. He and his men especially liked the stinging power of the plane’s 37mm cannon that could, if necessary, fire off some 30 rounds in 12 seconds. The hefty warhead had a definite arching trajectory, but one could eventually learn to “drop the shell right into someone’s shirt pocket as he walked along the beach,” said the ace.

Shomo and his men used the cannon effectively, especially against Japanese barge traffic that ran supplies from ships to shore installations. They would wait for the barges to get loaded up and head to shore with 75 fully armed troops or with food for 6,000 troops before they would pounce. A well-placed cannon shell at the base of the steering column would blow out the bottom of the barge, explode the fuel tanks near the steering column, and the whole vessel would be gone within ten seconds.

Both the Americans and others who used the P-39 were dismissive of rumblings about the jamming problems of the 37mm cannon. They found that proper maintenance was the key, along with utilizing the mechanical pistol-grip charging system to eject an occasional jammed shell and shove in the next shell. Most models of the craft carried 30 cannon rounds, so “our biggest problem,” Shomo said, “was running out of ammunition before we ran out of targets!”

The P-39 was literally built around its nose-centered cannon. That made it easy to aim, but also necessitated moving the engine behind the pilot to make room for the cannon in the one-man fighter. The arrangement gave the pilot superb visibility out the plane’s comparatively narrow nose and via the plane’s distinctive car-type doors on either side of the cockpit.

A few pilots, though, found it a bit disconcerting that the engine’s quickly-spinning, ten-foot long power shaft ran directly under their seat and near their “personal vitals” before emerging up front to link up with the propeller.

The plane saw action with the Americans in the South Pacific, the Aleutians, the Panama Canal Zone, Europe, and elsewhere. The British and Free French also put it to good use.

But it was the Soviets—engaged in the long and bloody life-or-death struggle with Nazi Germany—that adopted, adapted, and came to love the plane perhaps more than anyone else. It provided the Russians with the “push-back” that helped turn the tide in the Soviets’ “Great Patriotic War.” The hardy plane, constructed to withstand the recoil of its cannon and the stress caused by its long twisting power shaft, proved up to the challenge of the Russian winters and German defenses.

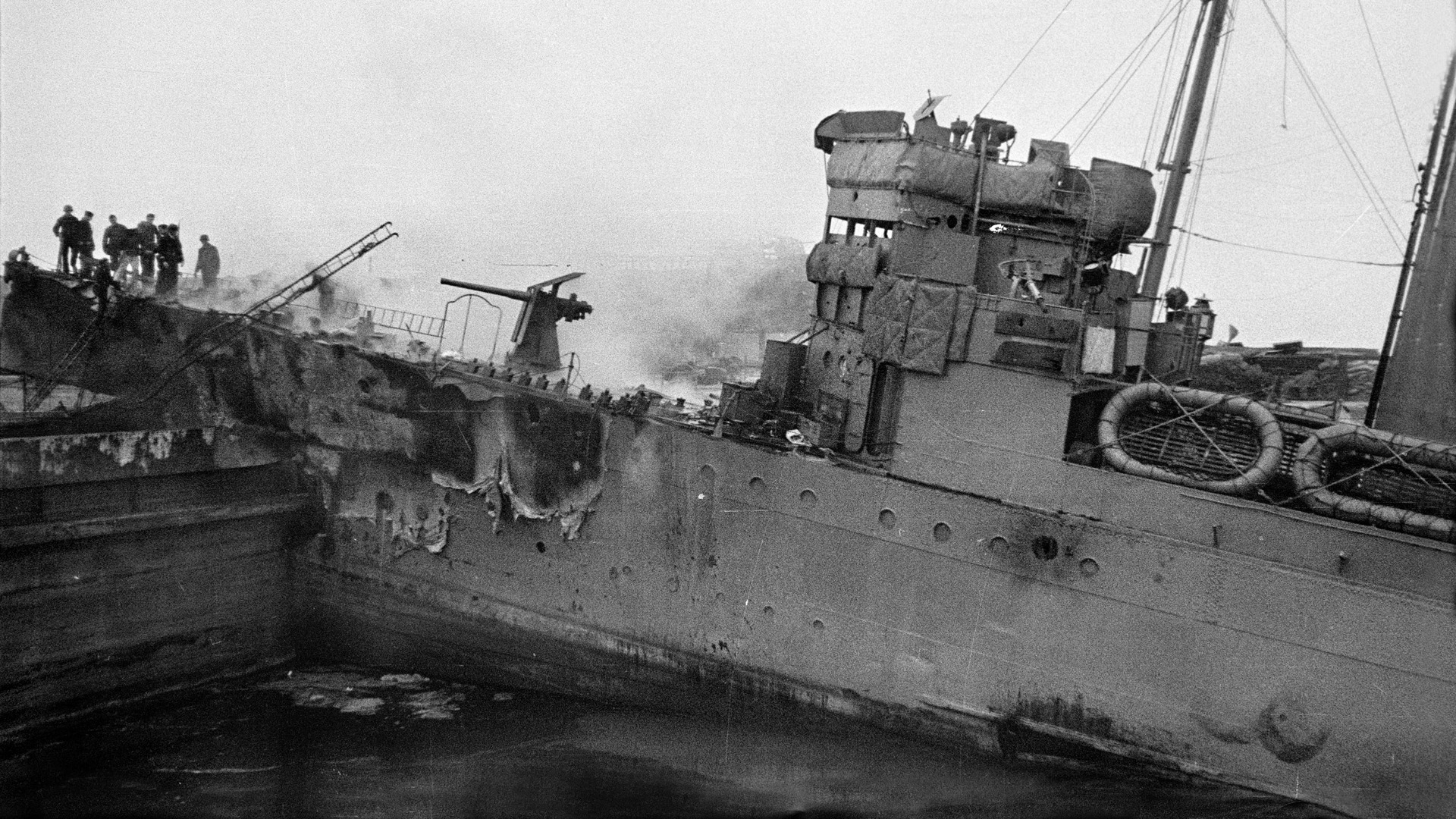

The first Airacobras arrived by ship in northern Soviet ports in late December 1941 or early January 1942 from Great Britain after the British had largely rejected the plane after testing it against their own Spitfires and Hurricanes as well as a captured Messerschmitt Bf-109E. The Soviets, desperate to delay and destroy the fast-moving invaders, quickly embraced the limited numbers of the early model P-39 with its smaller 20mm Hispano-Suiza cannon, four Browning .303-caliber machine guns, and two Browning .50-caliber machine guns.

World War II was fought with intense veracity worldwide, but rarely with more savagery than on the Eastern Front as the Red Bear first recoiled from the fierce German onslaught before regrouping and roaring back. The Soviets eventually lost more than 26 million people in that gigantic struggle that raged for four years across thousands of square miles.

The intensity of the struggle was such that a Soviet combat aircraft lasted, on average, only three months, and a Russian tank faired only slightly better. In the desperate winter of 1941-1942, Soviet forces lost one-sixth of their aircraft and one-tenth of their armored equipment every week!

The continuing flow of Lend-Lease materiel and improved tactics were crucial. The Soviets had to learn to make every bullet, tank and airplane count. They realized that the P-39 could be a potential game changer and they played to the plane’s strength in ground-attacks against the invaders, largely using it below 17,000 feet in a never-ending effort to keep the Luftwaffe away from Soviet ground forces and key installations.

Depending on the source cited, eventually anywhere from 4,423 to 4,750 P-39s were transferred to the Soviet Union, so that nation received roughly half of the 9,585 Airacobras built. And the P-39 comprised approximately one-third of all the Lend-Lease planes received by that nation. Most of those sent to the USSR came by ship to Iran and then flown by ferry pilots to Soviet bases, or flown directly from the factory to Fairbanks, Alaska, where Soviet ferry pilots flew them to the Soviet-German front.

The Soviets received several models of the P-39, although most were Q-models with the Allison engine, the 37mm cannon, and four .50-caliber machine guns—two located in the upper nose and two wing-mounted. At Soviet request, the wing-mounted machine guns were later deleted.

A number of Westerners have mistakenly said the Soviets used the P-39, with its powerful 37mm cannon, as a flying tank buster. While some German tanks may have been struck on occasion by the cannon, the craft was used to its best advantage to clear the skies, silence artillery and antiaircraft batteries, and disrupt German supply lines and land-based command centers. In simple fact, the Soviet P-39s were not supplied with armor-piercing 37mm ammunition, and the standard-issue high-explosive round was not capable of knocking out armored targets.

The pilot had a bit of a learning curve with the plane. Ejecting from the craft could be tricky, especially in a left spin that could lead to the pilot being struck by the tail assembly. A large number of glazing screws were used in the cockpit canopy and these were covered by rubber caps that dried out and fell off, exposing sharp threads that proved dangerous in tight aerial maneuvers or in ejecting from the plane.

To help prevent the center of gravity from shifting during firing, cannon casings and the links of the body-encased machine guns were collected in the lower front fuselage and emptied upon landing. The machine guns in the wings were heated by hoses from the plane’s radiator to prevent freezing in the cold Russian winters. The plane’s radio and navigational equipment were also appreciated by the pilots, permitting operations at night and in poor weather conditions.

The Soviet pilots fell in love with the fast, maneuverable, and well-armed P-39 that many found to be equal—or nearly equal—in speed to the German Bf109 and FW-190 fighters. Those enemy fighters could often be destroyed, the Soviets learned, with two or three short machine-gun bursts, while the strike of a single cannon shell could destroy or disable a German fighter or bomber.

The Soviets, on occasion, resorted to one technique that rattled their German adversaries to the core: using the sturdy-built P-39 to deliberately ram an enemy plane to bring it down. This was occasionally used to protect a fellow flier and to demoralize the German aviators in the process.

As the war progressed and the Soviets gained more air time and fighting experience, the pilots developed improved tactics. Key to that process was Captain Aleksandr Pokryshkin, who was to score 65 confirmed kills (including six shared) in the war and later go on to become Marshall of Aviation for the Soviet Union. He developed what he called a “Formula of Terror,” based on altitude, speed, maneuver, and fire.

Pokryshkin also developed what he called a “bookshelf” of pairs of fighters deployed toward the sun, one pair above another in upwards of four tiers. He also advocated taking the fight to the enemy by attacking Luftwaffe bombers over German-controlled territory before they had time to link up with their fighter coverage. Often, he found, the startled German bombers fled after dropping their bombs aimlessly over German troops rather than over Red Army positions.

Pokryshkin strongly advocated another method that the Germans found unnerving: he and his men would attack and destroy the lead bomber in each approaching echelon, either through “Eagle Strikes” from above or in deadly guns-blazing, head-on attacks. In the resulting confusion, the enemy would often flee in panic, randomly dropping their bombs in the process.

He also developed a technique whereby the Airacobra pilots would fly at a high speed into a combat zone slightly above the specified mission altitude only to slowly decrease altitude to gain momentum before climbing back up to altitude and then repeating the procedure. That way the P-39 would often be able to pounce on the enemy from on high with an “Eagle Strike.”

The Airacobra’s cannon and machine guns had separate firing triggers with the cannon fired with the thumb button on the top of the stick and the machine guns operated with the index finger on the front of the stick. Pokryshkin convinced his engineering crew to wire the cannon switch to the machine gun switch for a one-time experiment. His massed fire quickly blew a German bomber from the air. Soon all the P-39s in the squadron were firing with substantially increased firepower from a single trigger squeeze.

The Germans, for their part, also proved innovative in the use of their aircraft. As the war progressed, the Soviets encountered two Luftwaffe planes joined together to form one craft the Germans called the Mistel, or mistletoe. With assistance from a ground vectoring station, a P-39 pilot came across the Ju-88 bomber with a Bf-109 fighter attached to its upper fuselage with long struts. The engines of both German planes were spinning on the double-decker craft that the Soviets would later call a karaktitsa or cuttlefish.

The Airacobra pilot attacked, and both enemy planes fell burning to the forest below. Soviets on the ground reported that the Ju-88 exploded with the force of a 1,000-kilogram aviation bomb, creating a crater 10 yards in diameter and some five yards deep. Pine trees in a radius of some 220 yards from the crater were bent over and burned, and pieces of the German plane were found up to 2,200 yards from the crater.

Soviet pilots were advised that future attacks on Mistels should be undertaken with the notion of taking out the Messerschmitt pilot, rather than risking detonating the explosives in the Ju-88 with machine-gun and cannon fire. Once the fighter pilot was taken out, the Soviets learned that the Ju-88 bomber could be left to fly on and crash on its own.

Perhaps two of the more interesting units to use the Airacobra were Squadrons 10 and 12 of the Co-Belligerent Air Force, comprised of Italian pilots from the liberated portions of Italy. They cooperated with the Balkan Air Force on a number of missions against German forces in Yugoslavia during the war, and the Italians continued flying the P-39 until 1950.

The Airacobra was appreciated by those who flew the rugged workhorse, and disliked by many who never flew the craft that was first designed as a pursuit craft in 1936, well before the war. One noted observer said it’s “a pursuit fighter that was either born too early, or asked to stay on the front line and fight too long” on some necessary missions for which it was simply not designed.

Had it been given time to develop, provided with a turbocharger and later perhaps a Rolls Royce Merlin engine such as the P-51 Mustang, it might be given the respect that today is heaped on successor planes like the P-51. But it was the Airacobra’s low-level ground support capabilities, its solid firepower, rugged airframe, excellent low-level flying characteristics, and substantial numbers that gave the United States and its allies the time urgently needed to design and build the flashier and more power Mustangs and Lightnings that most people now associate with the winning of WWII.

“It was a great airplane, and its presence in New Guinea deterred the Japanese from landing in Australia, I can guarantee that,” asserts Colonel Charles Falletta, who totaled 16 aerial victories during the war, including six while flying P-39s over New Guinea. Most of the “rumors about the P-39 were from pilots who never flew the airplane,” contends Brig. Gen. Chuck Yeager. “It’s hearsay,” he concludes.

Yeager put in some 500 hours in the P-39 and once had to bail out over Casper, Wyoming, when a flight test of a new stainless steel prop went bad. The well-respected Yeager, who later became the first man to break the sound barrier, notes that “most pilots learn when they pin on their wings and go out and get in a fighter, especially, that one of the things you don’t do, you don’t believe anything anybody tells you about an airplane.”

A number of Airacobras have been saved, restored, and are on display today. By a quirk of fate, Lt. Col. Shomo’s P-39 was recovered in the early 1970s, restored, and is now at the Naval and Servicemen’s Park along the waterfront in Buffalo, New York. Another P-39, recovered from a lake in Russia, is now displayed at the airport in Niagara Falls, New York.

The P-39 Airacobra by Phil Zimmer references “Colonel Charles Falletta, who totaled 16 aerial victories during the war, including six while flying P-39s over New Guinea.” This is not true. Colonel Falletta only had 2 aerial victories, both while flying the P-39. Ref; USAF records and WWII Victories of the Army Air Force Arthur Wyllie

For “a pursuit fighter that was either born too early, or asked to stay on the front line and fight too long”, it was continued to be used by the Russians up until 1949.

Also early on, it was the USAAF that had Bell clip its wings, reducing the wing area, as well as the second stage supercharger needed for higher altitude performance.