By Jon Diamond

Ask anyone who was there and they will tell you that Papua New Guinea, especially along the northern coast, was a tropical hell.

An American infantryman from Grand Rapids, Michigan, in the U.S. 32nd Infantry “Red Arrow” Division claimed, “If I owned New Guinea and I owned hell, I would live in hell and rent out New Guinea.”

In addition to a suicidal and tenacious Japanese defense of the northern Papuan coastal area of Buna, the terrain, climate, and disease wrecked the regiments of the 32nd Division and the Australian battalions accompanying them. When corrected for the size of attacking forces, three times as many lives were lost in Papua than on Guadalcanal during a similar timeframe.

More than two-thirds of the Allied forces attacking Papua’s northern coast became afflicted with malaria; losses from disease were four or five times greater than from combat casualties. At the end of December 1942, Time magazine first brought New Guinea to the attention of the American public: “Nowhere in the world today are American soldiers engaged in fighting so desperate, so merciless, so bitter, or so bloody.”

It is no wonder that a GI fighting along the Buna front worried aloud, “God help us—we’re never going to get out of here alive.” Likewise, for the Japanese, one of their infantrymen recorded, “The road gets gradually steeper.… We are in a jungle area. The sun is fierce here…. We make our way through a jungle where there are no roads. The jungle is beyond description. Thirsty for water, stomach empty. The pack on the back is heavy.”

A Buna veteran described his American compatriots: “The men at the front … were perhaps among the most wretched-looking soldiers ever to wear the American uniform. They were gaunt and thin, with deep black circles under their sunken eyes. They were covered in tropical sores…. There was hardly a soldier, among the thousands who went into the jungle, who didn’t come down with some kind of fever at least once.”

New Guinea, 1,500 miles long, is the second largest island in the world, located immediately north of the Australian continent. Papua, the southeastern part of New Guinea, which occupies one-third of the total area, was administered by Australia. Australia’s military planners regarded it as a buffer against Japanese invasion of its Northern Territories.

The interior, to say the least, is inhospitable. The high mountains of the Owen Stanley Range dominate the topography, and the area is covered with jungles and swamps. The main town, Port Moresby, on the south coast with a population of 3,000 before the war, was comprised mostly of native Papuans. There are only a few villages along Papua’s northern coast, which include Buna and Gona. Lae and Salamaua are also on the northern coast near the Huon Gulf in northeast New Guinea. While the whole area is a flat, low-lying plain, the Buna area is made up of steaming, impenetrable jungle, coconut plantations, and fields of shoulder-high kunai grass.

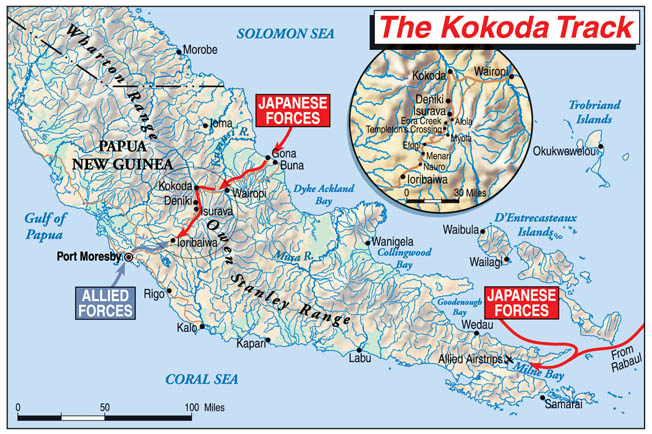

Away from Port Moresby, only native trails connected the north and south coasts, the most famous being the Kokoda Trail. The geographical and climatic obstacles to conducting military operations by either side was going to be immense in terms of troop movements, reinforcements, supply, and the care of the wounded.

Australia, the United States, and Japan were not prepared for a major war in the South Pacific, which was not only remote but also disease-ridden and ubiquitously wet. For the combatants to advance in New Guinea, they would need to be able to construct improvised bridges and roads where water and mud governed.

How did the Buna front become the locale for some of the most hellacious combat in the South Pacific?

After its amazing string of lightning successes after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese high command contemplated an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) goal to expand southeastward into the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, the New Hebrides, Fiji, Tonga Islands, and Samoa (Operation “FS”), to sever the long supply lines from the U.S. to Australia and New Zealand—in effect isolating the Antipodes from becoming American staging areas and bases for a counteroffensive.

The Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA) plan was to invade, with the assistance of the IJN, the Lae-Salamaua area in Northeast New Guinea’s Huon Gulf region. The seizure of Tulagi near Guadalcanal in the Solomons and its development as a naval air base would be postponed until after Lae and Salamaua had been taken.

The capture of these strategic points in eastern New Guinea, along with Tulagi in the southern Solomons (the latter accomplished in early May 1942 by the IJN), were intended to cut communications between these areas and the Australian mainland and to neutralize the waters north of Australia.

By postponing Operation FS, the more extensive southeastern assault, the Japanese left the South Pacific supply routes open to New Caledonia, Australia, and New Zealand—an omission they would later need to rectify.

The Japanese began their staging moves to take northeast New Guinea and Papua on March 8-11, 1942, when the IJA and the IJN’s Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) landed at Salamaua, Lae, and Fischhafen on the Huon Gulf. By occupying those locales, the Japanese were only 400 air miles from Cape York, Australia’s northernmost point directly facing Papua and, by operating out of Port Moresby, could deny the Allies the use of airfields in northern Australia.

By April 1942, Allied air attacks were causing extensive damage to Japanese air capacity and naval movements in the Solomon Sea. So, from April 1-20, SNLF troops landed in Fafak, Babo, Sorong, Manokwari, Momi, Nabire, Seroi, Sarmi, and Hollandia along the north coast of northeast New Guinea to seize and construct airfields there since neither side had firmly established air superiority over New Guinea.

It was becoming readily apparent that the outcome of the Pacific War, in large part, was going to be determined by either capturing enemy airfields or nearby suitable terrain to construct new ones to control the sea lanes as well as support future amphibious landings for expansion.

After successfully completing their Huon Gulf and coastal northeast New Guinea operations, the IJA and IJN were to mount a joint amphibious attack on Port Moresby on the south coast of the Papuan peninsula, which was ultimately thwarted at the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 4-8, 1942.

A second attempt at the seaborne invasion of Port Moresby was scheduled for the late summer of 1942 and would be made at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of Papua where, coincidentally, American and Australian engineers had begun constructing an airfield. The Japanese Milne Bay assault was to be concurrent with an overland IJA attack from Buna via the Kokoda Trail and across the Owen Stanley Range to seize Port Moresby.

The Japanese were under the misconception that a serviceable road for vehicles ran from Buna to Kokoda Village in the northern foothills of the Owen Stanley Range that could not be properly seen and photographed because of the jungle canopy. The IJA planners had made a flawed logistical decision that Formosan and Korean laborers along with IJA engineers could make such a road operational and build additional southward tracks to reach Port Moresby.

On February 21, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt cabled General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines and ordered him to leave threatened Corregidor for Mindanao and then proceed to Australia. On March 11, MacArthur and his retinue of staff officers left Corregidor in four PT boats and arrived at Mindanao; MacArthur and staff were then flown to Australia. There he was appointed Commander in Chief, Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) Theater by Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall at the direct request of the Australian government.

Australian Prime Minister John Curtin selected General Sir Thomas Blamey as Allied Land Forces commander in the SWPA. Curtin was glad to receive the “green” American 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions, both National Guard units, being hastily deployed to Australia’s defense since his own AIF troops were in the Mediterranean or in captivity, the latter after the fall of Malaya and Singapore. The 41st Division arrived in Australia in April 1942 and the 32nd in May.

When the American Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) gave MacArthur command of the SWPA, he was assigned, without a specific target date, to recapture Lae and Salamaua and to “seize and occupy Rabaul and adjacent positions in the New Guinea-New Ireland area.”

MacArthur’s staff knew that to retake Lae and Salamaua he needed an airfield on Papua’s northern coast; the logical place was Buna Government Station, with its small airfield, the “Old Strip.” Buna had been an Australian outpost facing Rabaul on the Solomon Sea and consisted of a government station called Buna Mission—just three houses—and the Old Strip. Buna Village, a half mile to the northwest, was simply a collection of native huts. At Gona, 10 miles north of Buna, was an older Anglican mission.

Buna was coveted as a future base and airfield complex by both the Japanese and the Allied war planners in the Southwest Pacific. MacArthur’s engineers had scouted Buna for the suitability of an airfield there. After the Allied engineers concluded that the coastal terrain was adequate, they departed. As the Buna area was likely to be a Japanese target, too, MacArthur directed the Australian commander in Port Moresby to secure it. MacArthur was most fearful of a Japanese seizure of Port Moresby, which the enemy could then use as a springboard to invade northern Australia.

Australian military planners, too, considered the Buna area as a major threat because it was “the northern terminus of the one good track to Port Moresby,” the Kokoda Trail. In June 1942, the Australians organized the 39th Battalion, a militia unit, along with a native constabulary unit to seize Buna. On July 7, company-strength elements of the Australian 39th Battalion were 30 miles north of Port Moresby, ready to start their ascent of the Kokoda Trail; eight days later, Company B of the Australian 39th Battalion was at the outskirts of Kokoda Village.

On July 24, the remainder of the 39th Battalion was ordered to get to Kokoda Village as quickly as possible from Port Moresby. That village lay in a valley 1,200 feet above sea level in the northern foothills of the Owen Stanley Range. In addition to a Papuan administration post and a rubber plantation, Kokoda Village also had a small airfield, which likewise was a main objective in Japanese strategic planning.

On July 15, MacArthur ordered the establishment of his forward base at Buna. Also, a new airfield was to be constructed at Dobodura, 15 miles south of Buna, where a grassy plain had been identified that would be large enough for both bombers and fighters. Allied reconnaissance flights had shown the Buna strip to be inadequate for the airbase that the SWPA commander was envisioning.

The Japanese, however, had beaten the Allies to the punch at both Buna and nearby Gona. On July 21-22, 1942, Japanese cruisers, destroyers, and transports landed a preliminary force of 4,400 engineers of the Yokoyama Advance Force (under Colonel Yosuke Yokoyama) and the South Seas Detachment IJA Headquarters, the latter which had captured Rabaul; all under the command of Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii.

Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, the IJA Seventeenth Army commander headquartered in Rabaul, would increase this advance force to 11,100 men with the addition of the IJA’s 41st Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Yazawa Kiyomi, and the remainder of the 144th Infantry Regiment. By August 13, the IJA would occupy the Buna-Gona area and transform the former site into a base of operations.

Soon after the Japanese landings at Buna, Yokoyama lost no time in sending his forward elements on their southerly march to Kokoda Village. This force, comprised of the 15th Independent Engineer Regiment, which would build depots and clear roads, and 1st Battalion, 144th Infantry Regiment, the main combat arm of the force, hit the Australians on July 28 in an effort to seize Kokoda Village and its prize airfield.

Initially, this force was tasked to assess the condition and quality of the roads and need for repairing the Buna-to-Kokoda road. However, the Yokoyama Force, instead of conducting a civil engineering reconnaissance, was ordered by no less than the Emperor and Imperial Japanese Headquarters to prepare for an overland attack to seize Port Moresby (Operation MO), under the command of IJA Seventeenth Army headquarters, without a thorough feasibility study.

A skeptical General Horii was dubious that a supply line of native porters (32,000 was deemed as a requisite number) could be maintained, whatever state the extant “road” was actually found to be in. In fact, the Kokoda Trail was a 145-mile mud path, no wider than three or four feet, that climbed mountains as high as 6,000 feet and crossed some of the most inhospitable terrain in the world, comprised of steep gorges, rapidly flowing streams and always wet, moss-covered rocks and logs.

Meanwhile, Port Moresby was being strengthened with the Australian 25th Brigade along with Allied air, engineer, and antiaircraft units.

The Yokoyama Advance Force was also awaiting reinforcements, which were to include the two remaining battalions of the 144th Infantry Regiment and a mountain artillery battalion, which had to forcibly land at Basabua, to the west of Buna near Gona, due to Allied air interdiction and then be ferried to Buna to reinforce Yokoyama’s command at Isurava.

On August 28, Hyakutake ordered Horii to advance to the southern side of the Owen Stanleys and await the outcome of a second assault—the IJN amphibious assault at Milne Bay, intended to seize the newly constructed Allied airfield there and to serve as a base for another naval assault on Port Moresby. The Milne Bay amphibious landings commenced on August 25; however, they failed and the Japanese evacuated their assault troops on September 7.

Without a concurrent amphibious assault on Port Moresby from Milne Bay, Horii was on his own without air cover from the IJN. Horii’s South Seas Detachment was becoming severely malnourished and ravaged by disease.

In early September, General Horii and IJA infantry from the 41st and 144th Regiments, arrived at Kokoda Village in bad shape; Formosan and Korean laborers and Japanese soldiers had to carry supplies to the front and the wounded back to Kokoda Village. Logistics were a nightmare for Horii, and he was behind schedule in his crossing of the Owen Stanleys to attack Port Moresby.

On September 16, 1942, the Japanese struggled up Ioribaiwa Ridge, from which the Australians had recently withdrawn to Imita Ridge to the south across the valley; the Japanese literally wept for joy since they could now see the plains and sea around Port Moresby. At night, from Ioribaiwa Ridge, the Japanese saw the searchlights of the Allied airfield on the outskirts of Port Moresby, 27 air miles away. This was as near to Port Moresby as the Japanese would ever get.

The Japanese supply system was stretched to its limits, and the offensive had resulted in a majority of the force being killed, wounded, and disabled by diseases—malaria, dysentery, dengue fever, and beriberi. The Australians and Papua’s unforgiving nature had halted the advance of the Japanese south from Buna over the Owen Stanley Range. Only 1,500 of the 6,000 troops that had left Buna in mid-August remained healthy enough to fight after just four weeks of strenuous marching and jungle combat.

A stiffened Australian resistance at Imita Ridge by two Australian militia battalions and later reinforced with more battle-hardened Middle East veteran formations of the AIF’s 28th Brigade along with a near-constant Allied air presence that attacked Japanese supply lines running back to Buna, compelled Horii to halt his drive on Port Moresby at Ioribaiwa Ridge and prepare defensive works while awaiting reinforcements.

However, on September 24, the Japanese high command ordered Horii to withdraw along the Kokoda Trail and establish defensive positions at Buna and Gona. The Japanese, who had positioned guns and dug weapon pits and trenches along the Ioribaiwa Ridge during the last week of September, withdrew from their positions on September 28 under attack by Australian infantry. This was a strategic withdrawal for the Japanese because of an increasing need for troop reinforcements at Guadalcanal.

With a nascent American corps comprised of the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions being trained in Australia, MacArthur needed a corps commander. Marshall fortuitously sent him Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger (West Point class of 1909). The 32nd and 41st Divisions, commanded by Maj. Gens. Edwin Harding and Horace Fuller, respectively, were also sent.

On September 10, MacArthur ordered Eichelberger’s I Corps headquarters to deploy Harding’s 32nd Division to New Guinea to ease the burden on the Australians retreating down the Kokoda Trail to the Imita Ridge prior to the Japanese high command halting Horii’s advance on the Ioribaiwa Ridge.

MacArthur committed the relatively green 32nd Division’s 126th and 128th Regiments to Port Moresby without any serious training in jungle warfare. Also, the 32nd Division, being a National Guard unit that was deployed early to Australia, missed the training that other Army ground forces divisions were acquiring stateside.

The two regiments reached Port Moresby by September 28, the day General Horii’s troops evacuated their positions on Ioribaiwa Ridge. However, due to shipping and air transport deficiencies, Harding’s four battalions of division artillery—48 field guns, including the excellent bunker-busting 105mm howitzers—were left in Australia. These two regiments were ordered to capture the extensive group of Japanese fortified installations at Buna. Eichelberger, however, was skeptical of the untried 32nd’s combat capabilities.

Because of the extensive coastline of northern Papua near Buna, troops of the 32nd Division sailed from Port Moresby on a motley collection of coastal craft and wooden schooners. These inadequate vessels were vulnerable to Japanese air attack and could not carry artillery, tanks, or heavy equipment. It was no wonder that the U.S. Navy officers did not want to risk their larger craft in uncharted waters against an enemy who controlled the airfields. Additionally, the Allied navies were busy combating Japanese surface ships in the waters off Guadalcanal.

Once committed to the defensive at Buna, the Japanese infantrymen and SNLF troops sought locations of concealment (i.e., trenches, rifle pits, coconut tree tops, pillboxes, camouflaged entrenchments, even entangled tree roots). If the Japanese concealment methods were successful, the American and Australian assault troops would never see the defenders and come under withering fire.

Since air strikes were limited by the density of the jungle canopy, the Allied attackers had to learn, often on the spot, to identify likely concealed defensive positions and probe them. Once identified, the Allies would blast them with bazookas, flamethrowers, tanks, and artillery.

Direct, large-scale infantry assaults gave way to smaller infantry units going forward with covering fire from a cooperating machine-gun or rifle unit. In this manner, alternating advance and covering fire, units would continue to move forward against the enemy positions.

An Australian after-action report recalled just how well the Japanese engineers had prepared the defenses along the 11-mile front of northern Papuan coastline that extended from Gona in the west to Cape Endaiadere to the east of Buna Mission and Giropa Point. Hundreds of coconut log bunkers, some reinforced with iron plates, others with iron rails and oil drums filled with sand, were constructed. In areas that were too wet for trenches and dugouts, bunkers were built above the surface and then concealed with earth, tree fronds, and other vegetation, making them essentially invisible.

The bunkers, which could contain from three to five machine guns, provided an intense interlocking field of fire on any advancing Allied troops. The bunkers were protected by infantry in open rifle pits located to the front, sides, and rear of the fortified entrenchments. Some infantry would be concealed in foxholes, under trees, or even in hollowed-out logs, while others simply waited in the jungle where they were heavily camouflaged. Snipers in the tall coconut trees or in concealed terrain positions were a major menace in both the American and Australian zones along the Buna front.

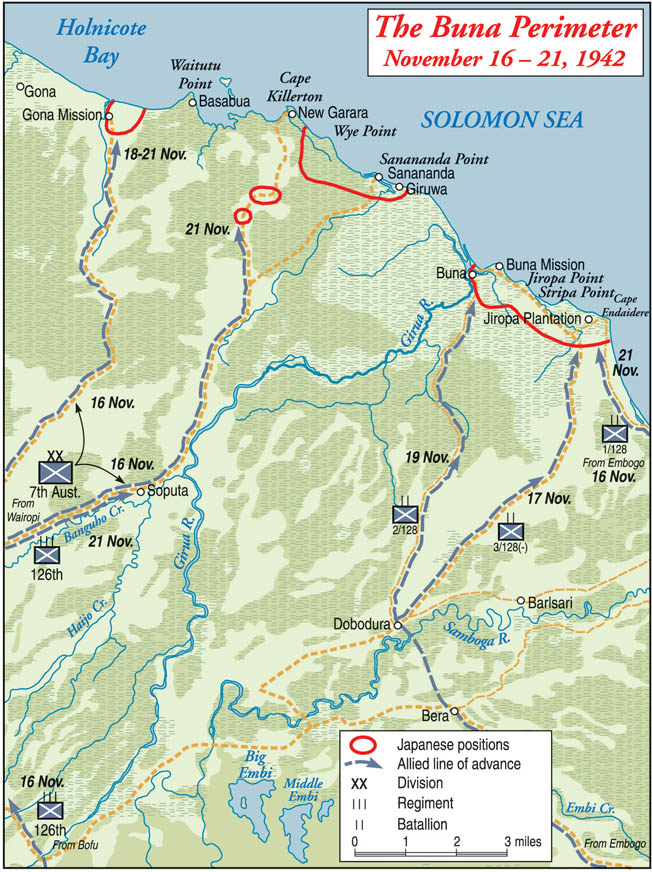

Another Japanese defensive line, to deter the 7th Australian Division’s advance, was built across the road leading from Soputa, just over seven miles inland, to Sanananda Point on the sea. The Girua River served as an inter-Allied boundary, with the Australians to the west of it, slogging through jungle trails to assault Gona and Sanananda Point.

The Girua River is about 50 feet wide until it disappears in the swamps southeast of Buna Village. The river eventually reaches the ocean through several mouths between Buna and Sanananda Point. Two other waterways were important in regard to the combat. The first was Entrance Creek, which opened into a shallow lagoon between Buna Village and Buna Mission. The other, Simemi Creek, runs north to the area between Buna’s Old and New Strips, and then parallels the northern side of the Old Strip to the sea between Giropa and Strip Points.

The area between Entrance Creek to the west and Simemi Creek to the east comprises the principal swamp on the Buna front and reaches inland to the vicinity of the villages of Simemi and Ango, which were in the center of the 32nd Division’s area of operations against Buna. This swamp is absolutely impenetrable with closely spaced trees up to 100 feet tall. The swamp’s floor, composed of tangled roots and underbrush, is always waterlogged.

Two large coconut plantations were present. The first, Government Plantation, was about 300 yards wide and situated between the mouth of Simemi Creek and Buna Mission. Duropa Plantation was much larger and ran south from Cape Endaiadere in the east toward Strip Point to the west.

To the southwest of Duropa Plantation was a large area overgrown with kunai grass, upon which was situated the Old Strip, a goal of the Allied advance. Allied control of the airfield would deny the Japanese another chance to seize Port Moresby by land and become a base for the Fifth U.S. Air Force. The Japanese had built a “dummy” field called “New Strip,” which was in another grassy area to the east of Simemi Creek and ran in an east-west direction.

As the crisis on the Kokoda Trail passed after the Australians reoccupied Kokoda Village without any opposition on November 2, MacArthur had to protect his newly acquired airfield at Kokoda and another at Dobodura, about three miles south of Ango. Japanese possession of Buna could ultimately threaten both airfields, so MacArthur was set on a campaign of annihilation against the Japanese on Papua’s northern coast rather than the less costly strategy of starving them into capitulation.

The Japanese, on the other hand, insisted that Buna be held at all costs and that the Dobodura airfield, 10 miles south of Buna, be destroyed. The loss of Dobodura would hamper Allied reinforcements of Papua and weaken their capacity for air attacks. Tokyo reasoned that losing Buna would jeopardize future operations on New Guinea and the Japanese position on Rabaul. To that end, the Japanese were resolved to defend the Buna front to the last man.

The plan envisioned by MacArthur was for a general advance by the Australian 7th Division to commence on November 16, 1942, driving the Japanese back along the Kokoda Trail while the U.S. 32nd Division would make a secret, wide, enveloping eastward march and then attack westward along Papua’s northern coast against the Buna front. The dividing line between the Australian and U.S. troops was to be the Girua River.

However, the Japanese troops situated there were well protected against any attack from inland. Swamps and dense jungle channeled the Allied attackers down a handful of trails, where a Japanese machine gun in a reinforced pillbox could hold off a battalion. The Australians, with the Americans advancing along the northern New Guinea coast, would expend much blood attempting to wrest control of Buna from the Japanese.

During the remainder of October and the early part of November 1942, the 32nd’s 126th and 128th Regiments continued to move into position while the 127th Regiment remained in Port Moresby. The 2nd Battalion, 126th Regiment, serving as the force’s left flank, marched to Buna overland via the Kapa Kapa Trail, a rugged track climbing more than 8,000 feet over the Owen Stanley Range; this unit sustained casualties from noncombat causes and disease.

After five grueling weeks, the battalion reached Soputa on November 20. The exhausted Americans referred to being on this trail as being “in green hell.” To maximize time and effort and avoid an enervating march through the Papuan jungle, the three battalions of the 128th Regiment were airlifted by Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney’s Fifth Air Force transport planes to an improved airstrip at Wanigela Mission on Collinwood Bay, roughly 65 miles from Buna. Motor barges then ferried the 128th along the Papuan coast to Pongani, just over 20 miles from Buna.

There the troops constructed a landing field, which enabled the other two battalions of the 126th Regiment to be airlifted to this new site on November 9-11. All told, approximately 15,000 infantrymen and supporting troops were ferried to the Buna area by C-47s.

Kenney turned the Fifth Air Force into a multidimensional unit that included troop transport and supply and aerial artillery for troops who lacked field artillery. With innovations perfected by his B-25 Mitchell and A-20 Havoc medium bombers, the daytime interdiction of Japanese coastal shipping and reinforcements to their New Guinea garrisons was stepped up. In 1942, these were revolutionary tactics, and Papuan laborers and Army engineers began building airfields in northern Papua, notably at Dobodura, located south of Buna and east of the unfordable Girua River, to give Kenney’s planes a base closer to the combat zone to accomplish their various missions.

In mid-November 1942, Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi was given command of the newly-formed IJA Eighteenth Army for operations in New Guinea and headquarters at Rabaul. Adachi was to operate under Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura, commander of the Eighth Area Army. Imamura was directly tasked by Prime Minister Hideki Tojo to first recapture Guadalcanal and to hold and consolidate at Buna. In the future another land assault would be planned against Port Moresby. Imamura’s Area Army comprised Adachi’s Eighteenth Army and the Seventeenth Army, under Hyakutake, the latter committed solely to the campaign on Guadalcanal.

Despite intensive Allied bomber interdiction of Japanese reinforcements and mountain guns from Rabaul, Adachi amassed 2,000 to 2,500 troops for the defense of the Buna area, including about 1,800 of whom had not participated in the overland attack on Port Moresby.

Buna’s Japanese defenders were comprised of IJA formations, SNLF units, engineers, gunners, and service troops. Some had just landed, while about 100 infantrymen of the 144th Regiment had survived the retreat up the Kokoda Trail, which claimed the life of General Horii, who drowned in the fast-flowing Kumusi River trying to escape to Lae.

By November 18, the American 128th Regiment’s 1st Battalion was between Hariko and the Duropa Plantation on the northern coast’s track; the 126th’s 1st Battalion was utilizing the same rudimentary trail coming up from Oro Bay. The remainder of this regiment was in position near Inonda.

The 3rd Battalion, 128th Regiment, was near Simemi, while at the grassy open plain at Dobodura elements of the 128th’s 2nd Battalion assisted with airfield construction. Food and ammunition would have to be airlifted to this new field since Japanese air interdiction, much like the Allies’, had strangled coastal supply by motor barges and schooners. The remainder of the 2nd Battalion established a division reserve at Ango.

Without a harbor and with swamps and creeks protecting it on the inland side, Buna would have to be approached along four jungle trails, each approximately 12 feet wide, but always prone to becoming washed out by tropical downpours. To that end the American engineers of the 114th Regiment were constantly laying down coconut log-surfaced corduroy roads to enable jeeps to bring up supplies and evacuate casualties.

The American approach to Buna was confined to two routes––one between Simemi Creek and the east coast and the other on the west side of the swamp along the Ango trail toward Buna Mission and Buna Village. The two routes lacked lateral communication, requiring two days to march from one flank to the other. More importantly, the Americans had little intelligence on the enemy opposition and location of defensive fortifications they would soon face.

Adachi’s Buna front, starting in the west at the Girua River near Buna Village and extending to Cape Endaiadere in the east, was just over three miles long and less than a mile from the coast. The Japanese had a motor road from Buna Mission to the bridge at Simemi Creek, which enabled lateral communication and reinforcement.

Specifically, the entrenched defensive works at Buna Mission ran slightly southwest to Entrance Creek and then turned north to enclose an area called “The Triangle.” The line of Japanese pillboxes and rifle pits then moved eastward across a grass-covered area called Government Gardens and then ran toward the coast through Government Plantation, ending at Giropa Point.

The defense of Buna Village and Buna Mission, the western sector, was in the hands of Captain Yoshitatsu Yasuda and his Yokosuka 5th SNLF and the 5th Sasebo SNLF, veterans of China and Malaya. Yasuda had installed heavy barbed-wire entanglements along this area to thwart an advance from the south. The SNLF units were deployed in a honeycomb of bunkers on the main approach between the swamps and in the coconut grove and gardens behind.

Other combat troops at Buna were the survivors of Tsukioka Unit’s three-month ordeal on Goodenough Island after their landing barges for the Milne Bay amphibious invasion were interdicted by Allied air patrols along with elements of Horii’s retreating South Seas Force.

About 500 yards southeast of Giropa Point, more entrenched positions were situated along the western end of the Old Strip, which had been built by Australian forces before the July 1942 Japanese invasion. It had been used by Japanese naval aircraft in August but had been heavily bombed and put out of action with several disabled Zero fighters and transports left abandoned on the runway.

Enemy positions continued eastward between the “Old” and “New” airstrips and ran onto a wooden causeway more than 40 yards long spanning the Simemi Creek then skirted the northern edge of the New Strip through the Duropa Plantation to abut the ocean half a mile south of Cape Endaiadere.

This eastern Japanese flank, under the command of Colonel Shigemi Yamamoto, was defended by the 3rd Battalion, 229th Infantry Regiment, which had captured Canton and Hong Kong and, until mid-November, had been at Gona.

Miscellaneous units included a heavy antiaircraft battery of the 73rd Independent Unit, a mountain artillery battery of the 3rd Battalion, 55th Field Artillery Unit, and 700 replacements for the 144th Infantry Regiment. During the initial two weeks of the Allied thrust on Buna, the American troops would face mostly fresh, fit, well-equipped Japanese troops.

Advancing American infantry first had to learn how to locate the camouflaged enemy bunkers, with forward units often being mown down by Japanese machine-gun fire, and then making costly frontal or flank attacks, the latter by crawling through swampy terrain. The source of the gunfire couldn’t be identified because Japanese machine guns and Arisaka rifles used flashless gunpowder. Sometimes advancing American infantrymen were allowed to pass the well-concealed Japanese positions before the defenders opened fire on the rear echelon of the patrol from all sides, inflicting heavy casualties.

On November 19, 1942, the Buna operation started with the 128th Regiment’s 1st and 3rd Battalions marching toward the Japanese positions running from Simemi Creek along the New Strip to the ocean. With the 3rd Battalion to the southwest of the “dummy” airfield at New Strip and the 1st Battalion on the coastal trail moving toward the Duropa Plantation, they met with unseen Japanese machine-gun and rifle fire. The 128th Regiment’s two-battalion march was stopped abruptly as the Japanese, possessing lateral lines of communication, quickly reinforced their positions.

Two days later, a frustrated MacArthur issued a directive to General Harding for the storming of Buna’s defensive works: “All columns will be driven through to objectives regardless of losses…. Take Buna today at all costs. MacArthur.”

Harding ordered a frontal assault that day along the Japanese easternmost positions after a preliminary bombing raid and mortar attack, since there was no American artillery present. Again, well-aimed Japanese machine-gun and mortar fire and snipers curtailed the American attack.

In addition, the Japanese would retreat during aerial bombardment to reinforced shelters and then sneak back to their pillboxes after the air raids to be ready at their machine guns once the Americans advanced.

Also on November 21, the 2nd Battalion, 128th Regiment, which had made the grueling Kapa Kapa Trail march, was stopped by the enemy at The Triangle south of Government Gardens in the western sector. The terrain there was mostly knee-deep swamp water that ruined radios, soaked mortar propellant, jammed machine guns and rifles with muck, and disoriented the GIs, especially in the darkness.

Entrance Creek, west of The Triangle, was unfordable for a flanking maneuver, except at sites well covered by Japanese machine guns and barbed wire that prevented the Americans from getting close.

On November 22, the 2nd Battalion, 126th Regiment, which had been supporting the Australian 7th Division, was released by the Australians to support the 2nd Battalion, 128th Regiment, struggling in The Triangle and at Entrance Creek.

General Harding formed two large task forces out of his surviving 3,500 combat troops; the 2nd Battalions of both the 126th and 128th Regiments would operate to the west of the large swamp area and were designated Urbana Force. The smaller of the two forces, under the command of Colonel John Mott, was tasked with assaulting Buna Village and then advancing onto Buna Mission.

East of the swamp, the larger force, dubbed Warren Force, was comprised of the 1st Battalion, 126th Regiment, and the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 128th Infantry Regiment, along with some Australian elements, all under Brig. Gen. Hanford MacNider. Warren Force was ordered to attack the Eastern Sector’s defenses from Giropa Point to Cape Endadaiere. This constituted the last Allied troop movement prior to reinforcements arriving on the Buna front.

On November 24, Urbana Force moved against The Triangle area and, after a day of crawling through the fetid swamp, reached a point beyond Entrance Creek adjacent to the trail to Buna Village to the northwest. The Triangle, a deep enemy salient of interlocking machine guns and mortars, could not be approached from the east, as both swamp and open kunai grass areas impeded advances. Thus, any further movement of Urbana Force would have to be to the northwest of The Triangle in the direction of Buna Village.

On November 26, the fighting shifted to the Warren Force area. Elements of the 3rd Battalion, 128th Regiment and 1st Battalion, 126th Regiment attacked Japanese positions at Duropa Plantation after aerial and artillery bombardment, the latter from one American 105mm howitzer battery, six Australian 25-pounders, and one mountain howitzer just airlifted to the front.

Target identification by Allied fighters and ammunition resupply was problematic, however. The preliminary aerial and gun bombardment had not destroyed the Japanese reinforced bunkers, so the infantry attack sputtered under heavy enemy machine-gun fire and no further attempts to reduce the defensive fortifications were made for 72 hours. A further hindrance to the Warren Force advance was the strafing by Japanese fighters from Lae.

On November 30, a new offensive failed on the Urbana Force front west of Entrance Creek, while a two-battalion assault, without the planned Australian Bren gun carriers, faltered in the Duropa Plantation to the east.

Thus, the Japanese defensive line along the Buna front was undented and as strong as it had been almost two weeks earlier, after inflicting about 500 American casualties. Combat and noncombat casualties, from malaria, dysentery, and scrub typhus, reduced the 32nd’s battalions to half strength.

MacArthur’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, visited Harding and recommended a leadership change to MacArthur, who then ordered Eichelberger to embark for Buna on December 1 and take over command of Allied forces east of the Girua River and “remove all officers who won’t fight.… Relieve regimental and battalion commanders … put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies…. I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive.”

Although the Japanese had held their positions, they, too, were suffering increasing attrition and waning morale. Enemy diaries found at Buna revealed entries from December 1 that “they had been waiting for reinforcements for the past four days” and that “My body will be buried in New Guinea and become fertilizer for the soil of Buna,” and “Now we are waiting only for death.”

Allied logistical hurdles were being overcome as 105mm howitzers arrived at the Buna front courtesy of Kenney’s B-17s. Australian-crewed Bren carriers and M3 Stuart light tanks reached Eichelberger and were employed on December 5 and 18, respectively. An increased shipment of supplies by both air and sea started to arrive.

Eichelberger reorganized his forces somewhat and installed new local commanders. The 32nd Division’s artillery officer, Maj. Gen. Albert Waldron, replaced Harding. Brig. Gen. Clarence Martin assumed command of Warren Force, while Urbana Force was to be led by Colonel John Grose. Eichelberger’s I Corps headquarters was combined with the 32nd’s to become Buna Force Headquarters, positioned at Simemi Village. Junior officers and enlisted men were learning some jungle craft and acquiring combat experience.

A three-battalion attack began through the Duropa Plantation on December 5, 1942, with supporting Bren gun carriers; however, these were all quickly disabled by Japanese snipers in trees, infantry with explosives, and tree stumps. Other companies attacked the New Strip’s western edge and the bridge crossing Simemi Creek. The Japanese positions could not be reduced, so gains were measured in yards. Warren Force would make repeated attacks on the enemy from December 6-14, but despite MacArthur’s demands could not break through the Japanese line.

On the Urbana Force front, on December 5, platoon-sized elements of Company G, 126th Regiment succeeded in driving east of the Girua River to the sea and separated Buna Village from Japanese reinforcements at Buna Mission and Government Station. The 126th’s E Company rushed in to help repel Japanese counterattacks along the coast.

The enemy defensive line in the western sector had finally been pierced, albeit with many casualties, including the 32nd’s new commander, Waldron, and an Eichelberger aide, who were wounded at the front.

To prevent the breakthrough near Buna Village from stalling, Eichelberger threw in reinforcements in the form of the 3rd Battalion, 127th Regiment, under Lt. Col. Edwin Swedberg, that was air transported to the Dobodura and Popondetta airields on December 9; they relieved the 2nd Battalion, 126th Regiment, on December 11.

Three days later, after patrolling and becoming familiar with the enemy fortifications, two companies from 3rd Battalion, 127th Regiment captured Buna Village following a heavy mortar bombardment. Among the few Japanese prisoners taken, some claimed that American mortar fire was very effective at wearing them down in their pillboxes and rifle pits since there was no advance warning to allow them to temporarily move to reinforced shelters.

To break the stalemate around Buna on the Warren Front, Eichelberger decided to wait until mid-December for light tanks and fresh Australian troops ordered by General Blamey to be brought up from Milne Bay.

Brigadier George F. Wooten’s remaining 18th Infantry Brigade battalions arrived along with seven light M3 tanks of X Squadron, Australian 2/6 Armored Regiment. This would considerably augment the Allied firepower at Buna since they had only the Australian “short” 25-pounder and a couple of American 105mm howitzers with limited ammunition.

From December 15-18, the three American battalions on the Warren Front moved forward against the Japanese across the entire line. On December 18, elements of the Australian 2/9 Infantry Battalion passed through the American lines with the accompanying tanks and reached Cape Endaiadere before being stopped by a new line of enemy bunkers as they swung west along the north coast.

Two M3 tanks were disabled by a Japanese antiaircraft gun, and a third was set ablaze, but with the 3rd Battalion, 128th Regiment, following up on the Australian advance an Allied coastal position just south of Cape Endaiadere was constructed.

Additionally, both Australian and American units, including 1st Battalion, 128th Regiment, were able to oust the Japanese from their fortifications at the eastern spur of the New Strip, forcing the enemy to retreat to prepared bunkers near the Simemi Creek bridge. About one-third of the Australians became casualties, but the reinforced Japanese bunkers at the Duropa Plantation and along northern side of the New Strip had been reduced.

On December 19-20, the Australian 2/9 Battalion and elements of the 3rd Battalion, 128th Regiment moved westward through the remainder of the Duropa Plantation on a 1,000-yard front. The 1st Battalions of the 126th and 128th Regiments eliminated all the Japanese bunkers on the east side of Simemi Creek to finally arrive at the bridge; however, the enemy had blown a 12-foot gap in this causeway that would require either repair or a flanking maneuver.

After unsuccessfully attempting to repair the gap, the Australian 2/10 Battalioncrossed the creek north of the bridge on december 21-23, threatening the Japanese defenders there. The 1st Battalion, 126th Regiment was able to get across the bridge by midday on December 23 and reached the southern edge of the Old Strip. The Australian and American battalions would now attempt to move, in parallel, along both the northern and southern sides of the Old Strip. Allied infantry painstakingly advanced about 500 yards, despite intense fire from enemy bunkers on the northern and central portions of the Old Strip.

After dark on December 23, the 114th Engineers repaired the gap in the bridge, enabling Australian M3 light tanks to cross Simemi Creek. An Allied tank assault across the bridge was made on December 24 to get to the northeast side of the Old Strip; however, the tanks were all disabled by the Japanese or the shell-pocked terrain.

An area designated Coconut Grove had fallen to the Americans back on December 16, but The Triangle had not yet been seized. On December 24, the 127th Regiment managed to create a bridgehead on the east bank of Entrance Creek after crossing it to the north above Coconut Grove on a footbridge constructed by U.S. Army engineers. Enemy resistance in The Triangle area would now be simply contained rather than frontally assaulted.

On Christmas Eve Day, the American infantry started a drive toward the northern coast to get between Buna Mission and Giropa Point, which would be achieved on December 29. Allied assaults on Christmas Day yielded few positive results as a strong pocket of Japanese bunkers prohibited the advance of either the American or Australian battalions.

On December 26-27, elements of the 1st Battalion, 126th Regiment were able to slowly advance with the assistance of an Australian 25-pounder artillery piece at the Simemi Creek bridge firing armor-piercing shells at the tenacious Japanese bunkers holding up the advance along the Old Strip.

By nightfall on December 27, the western end of the Old Strip was reached to enable a movement northward to Government Plantation, which geographically began in the east at the mouth of the Simemi Creek and extended to Buna Mission to the northwest.

On the morning of December 28, American patrols found that the Japanese had evacuated The Triangle area. The Americans also discovered the reason for the fierce enemy resistance in The Triangle. It contained over 18 mutually supporting reinforced bunkers that were interconnected by communication trenches.

The next day, four new M3 light tanks led an advance on Government Plantation, but progress was slow and the Allied infantry paused to await reinforcements. An Australian relief battalion, the 2/12 of the 18th Infantry Brigade, arrived on December 31 with more tanks.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Arnold, the 2/12 Battalion commander, led an attack that broke through to the northern coast at Giropa Point on New Years Day 1943. Elements of this force moved against the main enemy fortifications at Government Plantation to the southeast while other units of the 2/12 Battalion moved west to contact Urbana Force.

On January 2, the 3rd Battalion, 128th Regiment moved northwestward between the Old Strip and the coast to assist in eliminating the last of the Japanese pockets of resistance. Both Captain Yasuda and Colonel Yamamoto reportedly “died facing the Australian tanks approaching their command bunker.”

Progress on the Urbana front moved slowly since the capture of Buna Village two weeks earlier by the 3rd Battalion, 127th Regiment, largely because of the absence of Australian tank support—tank support that the Warren Force had benefited from.

After three months of frontal assaults, since the Papuan terrain prevented envelopments with large forces, the Japanese base at Buna was in Allied hands on January 2, 1943.

At Buna alone, of the original 2,000 Japanese defenders, 1,450 were known captured or dead with many more dying in the jungle or at sea. On the Allied side at Buna, the Urbana and Warren Forces had lost 620 men killed: 353 Americans and 267 Australians. Additionally, there were 2,065 wounded and 132 missing.

Malaria inflicted tens of thousands of medical casualties, largely because of the shortage of quinine. As for unit integrity, the 32nd Infantry Division was severely mauled at Buna and would up to a year of refitting in Australia to prepare for the next series of battles.

Eichelberger returned to Australia as I Corps commander to retrain and refit the two American divisions for future operations in New Guinea.

The U.S. Army’s commanders in the Southwest Pacific learned much from the Papuan campaign of 1942-1943, but the price was high. It was clear that U.S. Army units required more training. In contrast, the Australians had previously served in the Middle East.

After the victory in Papua in January 1943, MacArthur decreed that there would be “no more Bunas!” According to the official Australian history, “The primaeval swamps, the dank and silent bush, the heavy loss of life, the fixity of purpose of the Japanese, for most of whom death could be the only ending, all combined to make the struggle so appalling that most of the hardened soldiers who were to emerge from it would remember it unwillingly as their most exacting experience of the whole war … a ghastly nightmare.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments