By William E. Welsh

The Marines patrolling outside Khe Sanh Combat Base watched three enemy soldiers dart across an access road and dive into the protective edge of a tract of woods. After receiving permission from his company commander to follow them in the hope of capturing a prisoner to interrogate, the young Marine second lieutenant waved his platoon forward across an open field in pursuit of the enemy soldiers. They crossed two empty trench lines and walked unwittingly into an enemy ambush.

The Marines had not seen the enemy soldiers because they were concealed in trenches, bunkers, and spider holes. Automatic rifles, machine guns, and shoulder-held, rocket-propelled grenade launchers blasted the Marines from the front. Simultaneously, enemy fire raked their line from the side. “We were right in front of the NVA [North Vietnamese Army] trenches and bunkers,” said Corporal Gilbert Wall. “The air was filled with screaming, shouting, gunfire, and blood.”

Second Lieutenant Don Jacques, commander of the 3rd Platoon, Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 26th Marine Regiment, had led his platoon into the contested territory south of the combat base at 8 amon February 26, 1968. He and his men were scouting for enemy tunnels and trenches. The Marines knew that the NVA’s 304th Division was digging zigzag trenches from which it planned to assault the base from the south and east.

The three soldiers who darted in front of the platoon had done so to lure it into the ambush. The two sides became so intertwined that the Marines inside the base initially refrained from furnishing supporting artillery fire for fear of causing friendly casualties. Although Bravo’s 1st Platoon was sent to reinforce the hard-pressed 3rd Platoon, it was taken under concentrated mortar fire and pinned down.

In the ensuing firefight, the 3rd Platoon suffered five dead, one of whom was Jacques, 17 wounded, and 26 missing in action. Although the MIAs presumably were slain, the Marines dared not to try to recover their bodies until a later date. Although patrols had been allowed within sight of the base, after that point the only authorized movement outside the perimeter was to repair defensive barriers.

While there were other troops guarding the perimeter of the base that might have been sent out to assist the beleaguered 3rd Platoon, it was a conscious decision of Colonel David E. Lownds, the commanding officer of the reinforced 26th Regimental Command and the base commander, not to send more men outside the wire. His primary mission was to defend the combat base, and he could not afford to strip units defending the perimeter from their positions to send them on rescue missions in which they might also be ambushed. Such a move would jeopardize the security of the combat base and leave it vulnerable to a major attack.

Even so, some of the Marines at Khe Sanh could not find it in their hearts to forgive Lownds. It was one of the brutally tough decisions he had to make while serving as commanding officer of the combat base from August 14, 1967, to April 12, 1968.

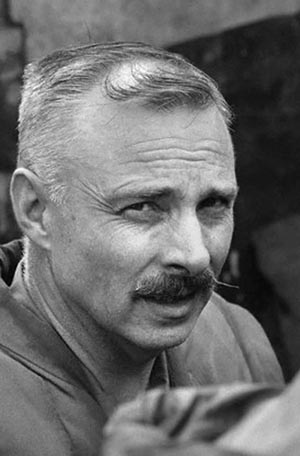

Lownds arrived at the combat base in the summer of 1967 to take command of the 26th Marine Regiment. The 46-year-old colonel had an impressive résumé that included both combat and staff work. As a junior officer, he had led a platoon in the 4th Marine Division during the fierce Pacific battles at Roi-Namur, Saipan, and Iwo Jima in World War II. Afterward, he served in a variety of staff assignments for the 2nd Marine Division during the Korean War.

Khe Sanh Combat Base was situated in the Quang Tri Province of South Vietnam 14 miles south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and four miles east of Laos. The Marines arrived at Khe Sanh in 1966. Shortly after their arrival, the Navy Seabees arrived to improve a primitive airfield that the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) had established on the Khe Sanh plateau four years earlier. Although initially sited next to the airstrip, the U.S. Special Forces Civilian Irregular Defense Camp was later relocated four miles southwest of the combat base.

The combat base and the airstrip helped U.S. forces monitor enemy movement on the nearby Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos. The airstrip was situated on the 1,500-foot-high triangular-shaped plateau south of the Rao Quan River. Some of the tall hills on the south side of the Rao Quan were covered with double-canopy rain forest. The undulating ground between the hills was covered with 10-foot-high elephant grass and tracts of 40-foot-tall trees and bamboo stands.

The limestone hills northwest of Khe Sanh were known by their height in meters on military maps. The Marines were determined to hold the high ground to prevent the NVA from posting artillery on them that could bombard the combat base and airstrip.

The Marines had fought a series of sharp company-sized engagements with the NVA in the spring of 1967 for control of key hills around the combat base before Lownds’ arrival. The Marines captured Hills 881 North, 881 South, and Hill 861; however, they withdrew in the summer of 1967 from 881 North as part of a scaling down of forces at the combat base. Events would show that abandoning 881 North following the Hill Fights was a mistake since the enemy reoccupied it.

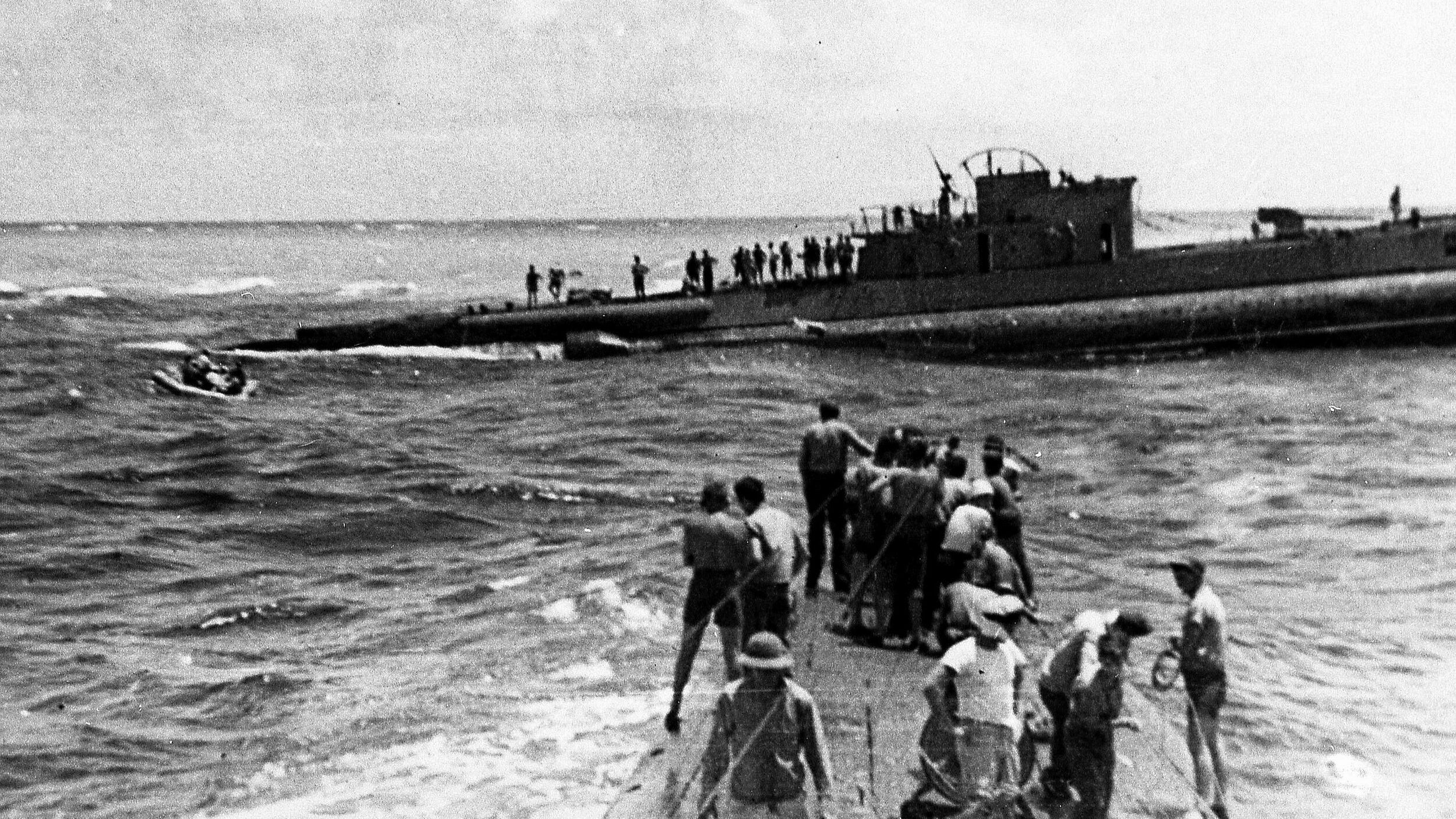

The only road into the combat base from the east was National Route 9, a one-lane dirt road that crossed dozens of streams between Khe Sanh and the Rockpile, the closest Marine combat base situated 12 miles east. As the siege of Khe Sanh progressed, the North Vietnamese cut the road. This forced the Marines to rely on cargo aircraft, such as the C-123 and C-130, for supplies and ammunition.

The company-sized garrisons on the hills required daily resupply by helicopter. Lownds ordered small numbers of heavy mortars, recoilless rifles, and howitzers sent to the outposts to improve their ability to defend themselves against enemy attacks.

Army General William Westmoreland, the head of the joint command known as Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), had authority over all Marine forces in Vietnam. Lownds reported to Maj. Gen. Rathvon Tompkins, the commander of the 3rd Marine Division, who in turn reported to Lt. Gen. Robert Cushman, the head of the III Marine Amphibious Force.

Cushman had to follow Westmoreland’s orders, even when he felt that it was in the Marine Corps’ interest to take a different approach. Cushman’s predecessor, Lt. Gen. Lew Walt had frequently clashed with Westmoreland.

The Marines had been reluctant to garrison Khe Sanh, which they deemed too isolated to bear any real strategic significance. But Westmoreland insisted on it. He saw it as a way to bait the Communists into a large-scale set piece battle in which American firepower could inflict catastrophic casualties on the enemy. The Marines had already shown in the Hill Fights that they could break up enemy troop concentrations and supply depots with a combination of the artillery at the combat base, long-range 175mm howitzers positioned 10 miles to the east at Marine combat bases at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile, and ground attack aircraft and B-52 bomber strikes.

For the North Vietnamese, the capture of Khe Sanh Combat Base would be a major propaganda victory and put them in a position to outflank the string of Marine combat bases south of the DMZ. The NVA had its own formidable firepower consisting of Soviet-made long-range guns deployed in protected positions on Co Roc Mountain just across the border in Laos. They also brought forward 122mm rockets and deployed them on Hill 881 North.

In addition to frequent patrols that swept out from their fortified positions on the hills to the west that overlooked Khe Sanh, the Americans also had eight-man teams that conducted long-range reconnaissance patrols in enemy-held territory to the west and north of Khe Sanh. Added to this were sophisticated aerial reconnaissance and seismic and acoustic sensors that were dropped in the no-man’s land around Khe Sanh from U.S. Air Force aircraft. The Air Force processed data from the sensors at facilities in Thailand and forwarded it to Lownds and his staff at Khe Sanh. The information was used to determine targets for air strikes.

In December 1967, it became evident to MACV that the NVA was marshalling troops and equipment for a major assault on Khe Sanh Combat Base. The NVA 325C Division was advancing from the northwest against the outlying hills northwest of Khe Sanh, while the 320th and 324B Divisions were approaching from the northeast. In addition, the 304th Division was advancing from the Ho Chi Minh Trail to attack Khe Sanh from the west and south. The North Vietnamese established a corps-sized headquarters they named the Route 9 Front to oversee the 40,000 troops operating in the region.

By mid-January Lownds had about 6,000 Marines and support troops to defend the combat base and the key outposts to the northwest. He had all three of the battalions of the 26th Marine Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the 9th Marine Regiment, the 37th ARVN Rangers, and the 1st Battalion of the 13th Marine Artillery. Marines already held Hill 881 South and Hill 861, which were occupied by India Company 3/26 and Kilo Company 3/26 and three platoons from 1/26, respectively, but Lownds wanted other key outlying positions manned as well.

Lownds sent Lt. Col. Francis Heath’s 2nd Battalion of the 26th Marine Regiment to occupy Hill 558, which overlooked the Rao Quan Valley, and he dispatched Lt. Col. John Mitchell’s 1st Battalion of the 9th Marine Regiment to hold the rock quarry adjacent to the combat base to the west. Defending the combat base’s perimeter were elements of the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 26th Marine Regiment. The ARVN Rangers had their own perimeter attached to the Marine-held combat base to the east.

Lownds’ direct-fire assets inside the combat base consisted of 18 105mm guns, six 155mm guns, six 4.2-inch mortars, six M48A3 Patton tanks, and 10 Ontos, a tracked vehicle mounting six 106mm recoilless rifles.

Beginning in November 1967, members of the 3rd Engineer Battalion oversaw the improvement of the perimeter defenses at the combat base by the Marines defending it. They added a fourth layer to the existing layer of triple concertina wire and constructed a 33-foot-wide expanse of tangle-foot wire. Outside of these wire obstacles they placed double apron wire strung from eight-foot-tall posts. Inside the original layer of triple concertina wire they put a ring of Claymore mines. The Marines also used jellied gasoline known as fougasse on the perimeter. The mixture was stored in 55-gallon drums that were detonated by a Claymore firing device.

Lownds and his Marines were leaving nothing to chance as they hardened their defenses. “They’re going to attack and we’re going to inflict a heavy loss on them,” Lownds told his staff on January 13. He ordered all Marines to wear their flak jackets and carry their rifles around the clock.

The Marines tried but failed to retake Hill 881 North on January 20. While the Marines were bogged down, Lownds unexpectedly ordered them to break contact and return to their outpost. The reason for the change of plans was that Lownds had learned from an NVA prisoner that an enemy attack on multiple targets was imminent.

Lieutenant La Than Tonc had defected to the Americans at the combat base while the attack on Hill 881 North was in progress. Tonc was a NVA junior officer from the 14th Anti-Aircraft Company attached to the 325C Division. He told his interrogators that an attack would occur that night. He said that the NVA planned to make assaults against Hill 881 South, Hill 861, and the combat base itself. The enemy intended to capture the two hills in order to use them as positions for mortars and recoilless rifles that would be used to support a full-scale attack on the combat base. Although the attack that unfolded on January 21 was in some respects different from the one described by Tonc, it nevertheless bore much in common with what he had described. Based on the information gleaned from the defector, Lowndes wanted all Marines safely inside their perimeters on the night of January 20-21.

Shortly after midnight on January 21, 300 soldiers of the North Vietnamese 325C Division attacked the northwest side of Hill 861 held by Kilo Company 3/26. Mortar fire crashed down on the Marine bunkers and trenches as Communist troops streamed through breaches in the wire made by skilled NVA sappers. The North Vietnamese regulars charged into the perimeter yelling and firing their AK-47s as they ran. Marines rushed to man their heavy weapons, which included 4.2-inch heavy mortars, 106mm recoilless rifles, and .50 caliber machine guns. The close-quarters fighting lasted for six hours, but the well-led Marines prevailed and repulsed the determined attack. The casualties were suprising light, but Lownds sent a platoon to replace Kilo’s losses.

The attack on Hill 861 was eclipsed by a major NVA artillery, rocket, and mortar barrage on the combat base fired from the slopes of enemy-held Hill 881 North. A well-placed shot by a 122mm NVA rocket struck the largest ammunition dump at the combat base that was located next to the airstrip, sending a huge fireball into the sky and triggering subsequent secondary explosions as the 1,500 tons of bombs, shells, plastic explosives, and bullets cooked off over the next 48 hours.

The attacks of January 21 marked the official beginning of the 77-day siege that would end on April 8 when the First Air Cavalry Division arrived at the combat base after reopening Route 9 to traffic. Following the NVA attacks on January 21, Westmoreland ordered Operation Niagara, the Seventh Air Force’s support for Khe Sanh, to begin. A three-aircraft cell of B-52s arrived on average every 90 minutes, flying from either Guam, Thailand, or Okinawa to strike the target box. The target was selected based on intelligence data gleaned from detectors and sensors or the request of an air or ground controller. Added to this were the hundreds of strikes by Navy, Marine, and Air Force fighter bombers made each day.

As the siege began, Westmoreland criticized the quality of the Marine bunkers at Khe Sanh, stating that they were flimsy and overly reliant on sandbags that could not withstand direct hits from enemy rockets and heavy artillery. Cushman inferred that Westmoreland was unhappy with Lownds’ defensive preparations, and so he suggested they consider replacing Lownds. When Tompkins learned that Lownds was in danger of being sacked, he immediately came to his defense. Tompkins said Lownds knew the terrain better than anyone else. Cushman dropped the idea, and Lownds remained in his position.

Lownds met frequently with reporters who flew to the combat base during the siege. They grilled him about vulnerable bunkers and other matters, trying to find fault in his performance. Lownds shrugged off the criticism in a good-natured way. He told the reporters they were exaggerating.

Operation Niagara threatened the lives of the locals known as Montagnards. When they sought protection on the combat base, Lownds would not allow them through the gates. He did not have the supplies or room to accommodate them. Sadly, they had to fend for themselves. It seemed heartless, but Lownds’ top priority as the safety of the Marines.

Following the attack on Hill 864 and the ammunition dump explosion, the North Vietnamese launched five more significant attacks against the combat base and the surrounding outposts. A lull occurred during the peak of the countrywide attacks carried out by Viet Cong and North Vietnamese that began on January 30 during the Tet holiday, which was the Vietnamese New Year. The attacks at Khe Sanh resumed with a vengeance on February 6 when the enemy attacked Echo Company of 2/26 on Hill 861A in the early morning hours. The Marines fought, often hand to hand, with the 200 enemy soldiers who attacked through breaches made by sappers. The defenders called in supporting fire from multiple locations to help them repulse the enemy attack.

On the morning of February 7, the NVA launched a full-scale attack against the Lang Vei Civilian Irregular Defense Camp where U.S. Army Green Berets were deployed with several hundred Montagnard irregulars. Elements of two NVA divisions, supported by a dozen Soviet-made PT-76 light amphibious tanks, attacked the base from two directions. Although the stalwart Green Beret troops managed to knock out a few of the tanks with recoilless rifles, the NVA succeeded in overrunning the camp. The Green Berets had requested Marine reinforcements during the battle, but Lownds declined to send them. He justified his decision on the grounds that the North Vietnamese undoubtedly would have ambushed the relief column.

Over the course of the next two weeks in mid-February the Communists focused heavily on advancing their siege trenches toward the eastern end of the combat base where the ARVN rangers were deployed. The NVA attacked the ARVN Rangers on several occasions, but they were repulsed each time.

In mid-March Westmoreland informed President Lyndon Johnson that the NVA offensive against the combat base was over. Westmoreland launched Operation Pegasus, conducted by the 1st Air Cavalry Division, in early April. The airmobile troops battled the North Vietnamese in the Route 9 corridor over a two-week period. Their mission was to open Route 9 so that Khe Sanh could once again be supplied by road.

Colonel Bruce Meyers relieved Lownds on April 12. The Lion of Khe Sanh, as some called Lownds, was hailed by many as a great hero for his direction of the Marine forces at the combat base during the siege. Lownds had readily reinforced positions when he felt it was wise, but he showed great restraint in withholding reinforcements when he felt that a relief column might be ambushed and annihilated. That required sound military judgment.

Before the siege began, Lownds knew that the Marines would forever be remembered for their stand at Khe Sanh. “We at Khe Sanh are going to be remembered in American history books,” he said. It is important that history also remember the name of the man who stood up to the North Vietnamese at Khe Sanh.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments