By John E. Spindler

In the evening hours on a midsummer day in 102 bc, Roman Consul Gaius Marius decided that tomorrow was to be the day to confront the barbarians. Marius and his army had been trailing a pair of Celto-Germanic tribes, the Teutones and Ambrones, for the past few weeks. Starting from where the Isere River flows into the Rhone, the enemy’s route had led him to Aquae Sextiae, now known as Aix-en-Provence. Although the two sides had clashed previously, that engagement involved only a small portion of both the Roman and barbarian forces. Marius, in an unprecedented third consecutive term as consul, would learn if the past two years of training and conditioning his army had been worth the time, effort, and resources. More important, if Marius lost, the Teutones would have an open road to Rome.

The road to this crucial battle in southeast Gaul began years before with the rise of the Cimbri, who hailed from the Jutland peninsula. Looking for sufficient lands to settle, the Cimbri arrived in Noricum, the land of Roman allies known as the Taurisci in 113 bc. A miscommunication led to a local Roman commander’s attempt of a surprise assault on the Cimbri. The clash ended with a heavy Roman defeat the following year at Noreia. At that point, the Cimbri were joined by the Teutones, Ambrones, and Tigurini in their migration across Europe.

Another significant loss occurred on October 6, 105 bc, at Arausio on the Rhone River. Consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus led a consular army north from Rome to join forces with Proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio, whose army was already in the region dealing with border violations. Because Maximus lacked military experience and was a novus homo, the first of his family to serve in the Roman Senate, Caepio refused to serve under or even cooperate with him. Bad relations and jealousy led to separate plans and camps. Instead of having one of the largest Roman armies ever put into the field, the forces were divided with Caepio having erected his base in front of Maximus’s camp.

Without informing Maximus of his intentions, the proconsul hastily attacked the barbarians. His army was not only stopped, but the Cimbri and Teutones counterattacked and destroyed it. The barbarians quickly overran Caepio’s base and then annihilated Maximus’s army and camp. The resulting defeat was the worst Rome had suffered since the catastrophe at Cannae more than a century earlier. Approximately 80,000 legionnaires and 40,000 noncombatants lost their lives, leaving Rome open to being conquered.

For reasons unknown, the barbarian masses altered their path and veered away from Italy. With the Roman Republic spared for the near future, the Comitia Centuriata, which was the one of the three Roman voting assemblies that could declare war as well as elect the consuls, decided that drastic measures were needed. For that reason, they voted Marius to a second one-year term as consul. Having already been elected to the role in 107 bc, Marius normally would not have been eligible to serve as consul again until a 10-year period had elapsed. The Comitia suspended the rule as it had done previously in times of crisis to the Republic. Given the existing threat, the Republic needed an experienced commander with a successful military record to guarantee Rome’s safety.

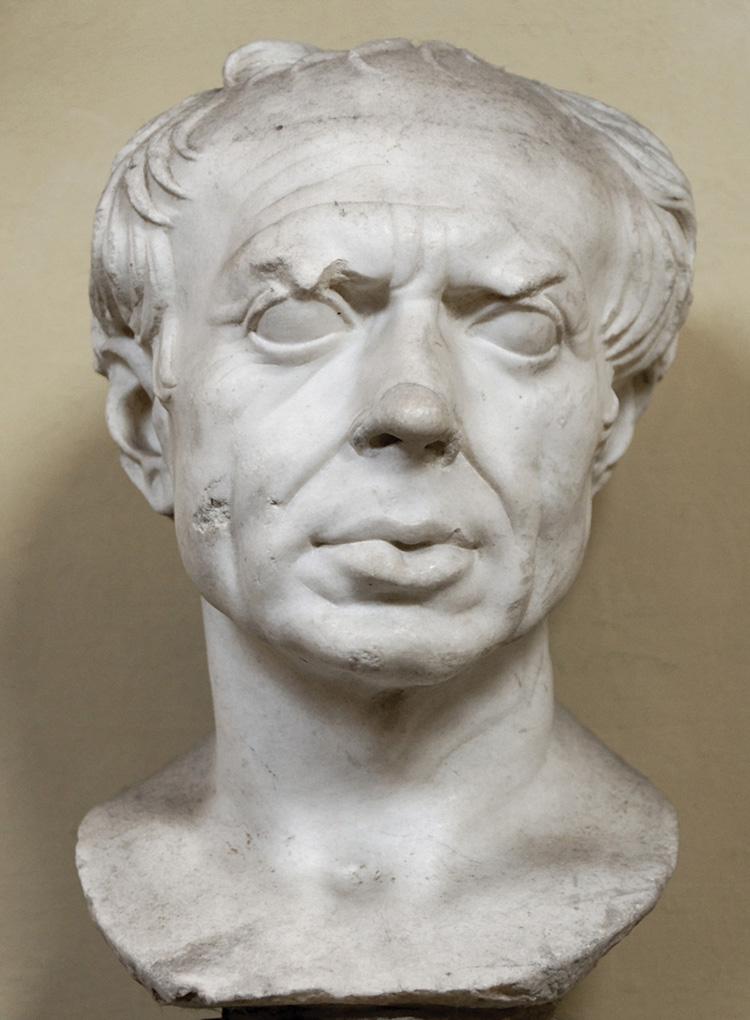

Born in 157 bcinto a plebian family of the equestrian rank 60 miles southeast of Rome in the Latium town of Arpinum, Marius opted to escape rural life and enlisted in the army. He rose through the ranks and proved to be a capable soldier. He was accused of political bribery in 116 bc, but survived an unsuccessful prosecution. In 115 bche was posted as quaestor of Hispania Ulterior (Further Spain) and the following year became governor of the province.

In 109 bcMarius served on the staff of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus in the conflict again King Jugurtha of Numidia. He returned to Rome the following year, though, and publicly excoriated Metellus for his conduct of the war in order to build political support for himself. Marius was elected consul in 107 bcand returned to Numidia where he campaigned for the next two years against the Jugurthine king. However, he was deeply resentful of Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s capture of Jugurtha. He returned to Rome and celebrated a triumph on January 1, 104 bc. Through these experiences, Marius became both an astute politician and an able tactician.

Marius arrived in Rome to begin the task of rebuilding the army. The reforms began during his first term as consul. The army previously had only been open to male citizens who owned property that allowed them to equip themselves for war. The small landowners generally constituted the core of the Rome’s heavy infantry, while the wealthiest of citizens possessed enough money to serve as cavalry; however, land-owning citizens were increasingly unable to fulfil the required numbers of an expanding army. Marius opened the army to all male citizens by actively recruiting volunteers from the poorer members. When elected again, Marius continued his policy of accepting recruits from the lower classes. He combined these new soldiers with the army raised by Publius Rutilius Rufus, a consul whose army had been training to fight the Celto-Germanic tribes.

With this opening of the army to all citizens, regardless of owning property or not, the option to make soldiering a career became available to the lower classes. Previously serving in the army was seen as a duty to be undertaken before returning to civilian life. Legions now became permanent formations. This new system replaced one that hindered the preservation of knowledge from past military campaigns and wars. Previously, when men were called back to perform their military service, a majority of the time they were assigned to a different legion. A lack of continuity fostered poor unit cohesion, especially early on in campaigning. As another of his reforms, Marius installed the silver eagle as the standard for every legion. This replaced the eagle, bear, wolf, boar, and horse, which were the five standards previously used.

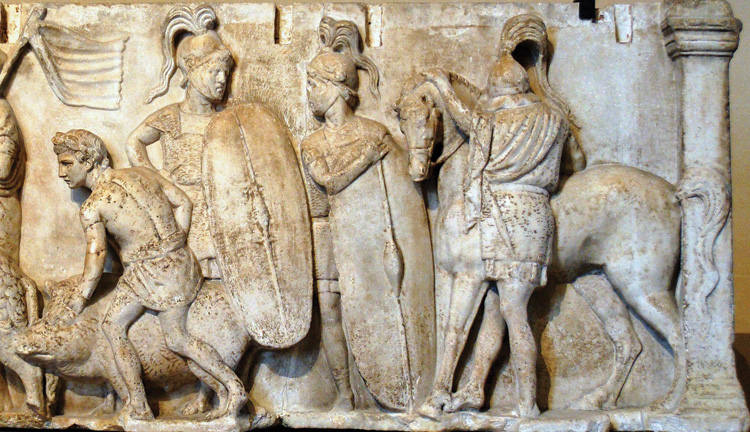

With an ever-increasing percentage of enlisted men from poorer classes came the challenge of furnishing them with arms since most lacked weapons. One of the Marian reforms mandated that the Republic furnish each soldier with the required clothing, armor, weapons, and gear. Outfitting a soldier became standardized and easier with the decision that almost all would serve as heavy infantry. Armed with two pila and a gladius, the legionnaire was protected in battle by his helmet, cuirass, and scutum.

Marius made a small but significant modification to the pilum. He replaced one of the two iron rivets that attached the tang to the shaft with a wooden dowel. Upon impact the wooden dowel would break and the pilum bend. A pilum could penetrate armor or lodge into an enemy shield. If the enemy soldier was charging and a pilum lodged into his shield, the end of the heavy shaft would often hit the ground and hold the shield in place, disrupting the enemy soldier’s forward momentum.

The Roman army’s central focus, from that point on, became its heavy infantry. As a result, the Romans relied on their allies to furnish cavalry. What is more, the Roman army relied on mercenaries for specialized roles. For example, they hired archers from Crete and slingers from the Balearic Islands.

In addition, Marius changed the Roman battle formation. For more than two centuries, the maniple was the standard tactical formation for Rome. With lines divided by age and experience, maniples of 60 or 120 men were arranged in a checkerboard formation to allow for rotation of fresh soldiers as a battle progressed. Although there were several reasons for this change, the most important one was to enable the Romans to adapt to different tactics employed by their enemies. No longer fighting the Macedonian phalanx with its lengthy sarissa, the maniple was at a disadvantage when it fought the Cimbri and their allies. These warriors from the north employed brute force to overwhelm the enemy. Therefore, the maniple formation was changed into the cohorts. A cohort consisted of three maniples and it increased unit strength to 480 men with 10 cohorts forming a legion. An advantage of the cohort over the maniple was that it was capable of acting independently. Thus, the Roman commander could employ his legion for multiple situations during combat instead of being only able focus on one task at a time.

With all legionnaires equipped the same, tactical flexibility was increased. In addition to changing the tactical formation, Marius amended the recent trend of a reduced baggage train by ordering all legionnaires to carry their own kits. This earned his troops the dubious nickname of “Marius’s mules” by elder statesmen who were used to the employment of slaves to carry everything when marching across the countryside. The consul initiated a strict training regimen to increase the stamina of his men and instilled a renewed sense of discipline. Combined with the reduced baggage train, the new training routine resulted in improved unit cohesion and speed. More than likely an important part of the training instituted by Marius was that his men learned to face the wild charges of the enemy and not be affected by them, either physically or psychologically. Unlike a majority of recent Roman commanders, Marius was a soldier’s general. He ate the same rations as his men and lived in the same conditions.

While waiting for the return of the barbarians, Marius had his men build a 16-mile canal from the Gulf of Stomalimne to his base of operations at Arelate, on the Rhone River, to keep the men busy as well as to improve the flow of his supplies. Bearing his name, the Fossa Mariana, Plutarch places its construction in 103 bc. Marius took advantage of the enemy’s hiatus by improving his intelligence network in the region as well as familiarizing himself with the terrain from the Rhone back to the Gallic-Italian border. The combination would allow the Romans to fight the Teutones on terms advantageous to them.

Marius learned the barbarians were on their way back eastward. Although the sources are conflicted on the location Marius chose for his base in the summer of 103 bc, he likely shifted it to Valentia. With six legions and a pair of cavalry formations, known as alae, supported by various auxiliary forces, Marius awaited the enemy in his fortified camp.

The barbarian army that was on its way back to invade Italy was once again a coalition of various tribes. For a number of years before the routing of the two Roman armies at Arausio, a few Celto-Germanic tribes had joined in the southward migrations and subsequent war with Rome. Named the Cimbrian War after one of the major migrating tribes, the Cimbri, the conflict lasted from 113 bcuntil 101 bc.

The Cimbri had migrated south from Jutland because of overcrowding. Along their journey, the Teutones, another tribe from the Jutland region, joined them. Perhaps an unspoken alliance between Cimbrian King Boiorix and Teutone King Teutobod was the cause of the two tribes joining together in their migration south through Europe, although the exact reason has been lost to history. Not surprisingly, the Ambrones, another Jutland tribe closely affiliated with the Teutones, participated in the large-scale migration.

The fourth tribe mentioned by ancient scholars that participated in what has been referred to as an anti-Rome alliance among the barbarian tribes was the Tigurini. They had already defeated the Romans twice. The Celto-Germanic tribes swept the Tigurini into their migrations along the borders of Italy. Estimates of the size of this barbarian army have never been accurately determined—the figures set forth by contemporary historians are almost certainly exaggerated. Contrary to popular belief, the Teutones and other warriors were organized with years of combat experience, including major victories over Roman armies. Indeed, the tribes exhibited a certain degree of discipline in battle.

Like the Romans, the Celto-Germanic warriors were armed with a javelin. They also fought using a seven- to 10-foot spear tipped with a soft iron head. Similar to the earlier Roman armies, the nobles and best warriors of the tribes were better armed. They wore armor, carried wooden shields, and wielded long swords. The standard Teutone warrior wore little or no armor with additional protection in the form of a wicker shield. Almost certainly a significant number of the barbarians would go into battle at Aquae Sextiae using Roman weapons and armor taken from dead or captured legionnaires. The barbarians’ typical battle tactic consisted of a ferocious onslaught at the start of a battle with lots of yelling and noise to intimidate their foes. Employed as a wedge, the charge worked exceedingly well against the standard Roman maniple formation, but would prove less successful in attacking the larger cohort.

After the rout of the Romans at Arausio, the Cimbri and their allies wandered westward. The tribes divided with the Cimbri and the Tigurini opting to plunder the Iberian Peninsula. The Teutones and the Ambrones marched farther north into Gaul. Unable to replicate their victories against the Romans, the Cimbri were defeated several times in Spain and marched back into Gaul and again enjoyed little success. At some point, the tribes linked up and agreed on invading Italy to defeat the Roman Republic. They hatched a two-pronged invasion plan. The Cimbri and the Tigurini marched into the Alps with the goal of invading Italy via the Brenner Pass. The Teutones and Ambrones took the route closer to the coast, invading through Liguria. In the early summer of 102 bcthe Teutones and the Ambrones, under the command of Teutone King Teutobad, arrived outside Marius’s fortified base along the Rhone River.

Marius felt secure inside the fortified camp. The Romans had several weeks to prepare their base for an assault. Through his intelligence network, Marius knew of the split in the enemy’s forces. His camp blocked the coastal route to Italy while fellow Consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus guarded the Alpine passes with a smaller army. After arriving in front of the Roman base, Teutobad had his army set up camp.

For several days the Teutones invited the Romans to leave their camp and engage in battle. The barbarians’ constant taunting agitated the Roman soldiers, who had to listen to the verbal abuse. Although the Roman rank and file desperately wanted to put an end to the haranguing through combat, Marius refused to begin the fighting. Instead, he kept his troops inside their base, much to the legionnaries’ displeasure.

Marius used the opportunity to allow the soldiers to patiently observe the enemy and study their tactics and methods. After many days spent waiting, the Teutones sent Marius an invitation for one-on-one combat with their champion. In response, Marius sent out a small, aged gladiator to mock his foes. Offended, the barbarians ravaged the nearby countryside.

When Marius still did not offer battle, the Teutones and Ambrones attempted to storm the Roman camp. “[The enemy] fought continuously for three days in the neighborhood of the Roman camp, trying every means to dislodge the Romans from their ramparts and drive them out on level ground,” wrote the Graeco-Roman historian Orosius. After multiple failed attempts that cost the lives of many warriors, Teutobad broke camp and marched his forces toward Italy with the belief that the Roman army would not be a hindrance to the plan. As the Teutones passed, they called out insults to the Romans and asked if they had any messages for their wives. Plutarch mentioned that the barbarian forces were so large that it took six days to march their entire army past the Roman camp. Perhaps it did take that long, but instead of a continuous line it was probably several large groups that passed by the Romans.

After the last of the Teutones and Ambrones had marched past, Marius broke camp. The Romans shadowed the barbarians. The past two years of intense training and carrying their own baggage allowed the Romans to easily keep up with Germanic tribes. Each night the Romans set up a fortified camp near their enemy, keeping difficult terrain in between the two forces. Marius knew he had only a short period of time to find the perfect place and right time to confront the Teutones. After trailing the barbarians for a few weeks over a distance of 120 miles, Marius realized the enemy was getting closer to Italy. He needed to confront them. As a result of living the majority of the past two years in the region, Marius knew the terrain very well. Upon reaching the vicinity of Aquae Sextiae, a village 19 miles north-northeast of the port city of Massilia, the Roman commander was finally ready to engage the Teutones.

In keeping with the tactic of securing the high ground, Marius elected to set up camp atop a hill at the end of a valley. Sloping down toward a river, the flanks of the valley plain were heavily wooded, which would negate the numerical advantage of the enemy. Teutobad would be forced to attack across a much narrower front. The Roman army was composed of 35,000 men in six legions augmented by 5,000 cavalry and auxiliaries. As for the barbarian army, it is estimated to have numbered upward of 110,000 warriors. The barbarians encamped along a river, the only local source of water. The Teutones took the best areas with the Ambrones on the periphery. Because of their large numbers, the Ambrones bivouacked on both sides the river.

The reason that Marius, who always used the terrain to his advantage, set up camp in an area without a water source is unknown. It might be that the hill he chose for the Roman encampment was the best site available. When the men started to complain about their thirst, Marius replied that water was at the base of the hill but they would have to fight for it. The priority was to set up their fortified camp, and this commenced soon after reaching the hilltop.

At one point, the Roman camp servants armed themselves and went to gather water for the men and animals. Upon reaching the river, they surprised some Ambrones celebrating at the river. A fight broke out between the two sides with the camp servants able to hold their own because the Ambrone warriors had recently feasted and were drunk. The din of fighting reached the Roman’s Ligurian auxiliaries, most likely posted as guards as the camp was built, who went to their comrades’ aid. More Ambrones joined the battle, as their camp was bisected by the river it would take time for all of them to ford the barrier of water. Soon afterward a detachment of legionnaires entered the fray and turned the tide in favor of the Romans. The legionnaires and the Ligurian auxiliaries routed the Ambrones, leaving the river choked with dead bodies. The Romans did not halt the fight at the river’s edge, but pushed their way into the enemy camp, massacring all. At this point the women took up arms and fought both their men, whom they viewed as cowards, and the Romans. Despite these new fighters the Ambrones were completely wiped out.

With so many men joining the battle, the Roman camp was without palisades and walls. The Romans remained on edge throughout the long night awaiting a barbarian reprisal that never came. The positive outcome was that Rome had finally had a victory over the northern tribes, which drastically boosted morale. Marius could tell his men that the enemy was not invincible. Teutobad did not retaliate that night nor the next.

A few days after the defeat of the Ambrones, both sides drew up for battle. By that time Marius had devised a clever plan. The night before the battle, he sent a detachment of 3,000 legionnaires into the woods bordering the valley field. Under the command of tribune Claudius Marcellus, the soldiers moved out after dark. If detected, the Teutones thought such a small force was of no consequence to the inevitable confrontation and took no actions to deal it. Marcellus’s orders from Marius were to withhold from engaging the enemy until the battle was well underway and then launch a surprise attack into the rear of the preoccupied barbarian army. It was up to Marcellus to determine the exact moment for the assault.

With Marcellus’s dispatch there was no going back for Marius; the coming day would see bloodshed. On this midsummer’s morning, both sides drew up their respective armies. Marius marched the Romans outside of the fortified camp and formed ranks. The legionnaires fighting this day would be witness to one of the rare occasions in which a Roman general decided to involve himself in the battle from its onset and the only battle in which Marius was known to have been an active participant. With his willingness to place himself in danger, Marius’s presence served to have a calming effect on his men as well as being an inspiration to them. Outnumbered at least two to one, the Roman commander had already achieved a tactical victory by having his enemy attack uphill across a battlefield that negated their numerical superiority.

At the base of the slope, Teutobad celebrated, having drawn the Roman army out of its virtually impregnable base. The Teutones were an experienced army with major victories over the Romans and probably knew that charging uphill against an awaiting enemy would be very difficult; however, the warriors were wrapped in an aura of overconfidence and Marius suspected their anxiousness. He knew it would not take much to break their disciple and sent his cavalry down into the field. Soon the plan worked and the barbarians charged up the slope after the cavalry. The Germanic tribes normally would charge in the wedge formation that had proved extremely effective against the Roman maniples. At Aquae Sextiae, the Teutones and the remaining Ambrones launched themselves uphill over difficult terrain that prevented the wedge formation from coalescing.

At the top of the slope Marius and his men watched the barbarians rush toward them. The Ambrones chanted their tribe’s name and those with shields struck them with their weapons. The Roman commander had his legionnaires wait until Teutobad’s warriors were within 15 yards, the effective range of the pila. After their use, the legionnaires would draw their gladii and charge the disrupted the barbarian army. When their foes reached the proscribed range, Marius’s heavy infantry let loose their pila upon the enemy. Some of the elite Teutones were protected by captured Roman scutum and armor. Although these may have withstood the rain of pila upon the ranks, most of the Germanic warriors were not as fortunate as they wore little or no armor and were lucky to wield a wicker shield. With a number of warriors either dead or wounded, the barbarian charge fractured.

With the Teutones severely disrupted by the pila assault, the legionnaires drew their gladii and looked toward their commander. Marius led the attack down the slope into the disorganized barbarians. The past two years spent training in the cohort formation proved to be worth it. The well-disciplined Romans slammed their shield wall into the Germanic warriors, knocking them off balance. The legionnaires then thrust their gladii into the barbarians. The short swords easily penetrated the barbarians’ wicker shields.

The Roman heavy infantry steadily drove the barbarians down the field, inflicting heavy casualties on them in the process. Isolated islands of stiffer resistance, comprised of those Teutones worthy to have captured Roman weapons and gear, held out longer than their brethren. In the end, their courageous stands proved futile. Despite the carnage and severe losses being inflicted upon them by the Romans, the will of the Germanic warriors refused to break.

After the exertion from a sustained push, the battle reached level ground where the momentum of the Roman charge began to falter. At this point, the Teutones started to form a shield wall of their own. This tactic was a defensive one and elicits the theory that their morale was definitely waning. Though their spears had proved less than successful against Roman armor, they had a range advantage over the gladius. A slight hesitation by Marius and his soldiers may have occurred as they sought to change tactics with the barbarians’ decision to form a shield wall.

At that pivotal moment, the 3,000 legionnaires under Marcellus rushed out from their hidden location in the woods and stuck the rear of Germanic army. Totally surprised by the effectiveness of this bold move, the barbarians’ formation and morale was irreparably shattered. Teutobad and the remaining Teutones and Ambrones fled back toward their camp as casualties rose exponentially. Within moments, the Battle of Aquae Sextiae descended into a rout and a Roman victory. Marius did not halt the surge, and his advance continued into the barbarian’s camp. The slaughter continued as noncombatants were now killed as the legionnaires sacked and burned the camp.

It is highly likely that the Teutone women tried to fight the Romans like the Ambrone women did a few days before. The two formations of Roman cavalry probably participated in the pursuit and destruction of the enemy at their camp. Though Teutobad managed to escape the Roman net, the Teutones joined the Ambrones as tribes on the path to becoming extinct.

After sacking the barbarian camp, the Roman troops decided to give the majority of the loot to Marius. As a tribute to the gods for this victory, Marius piled his spoils into a great pyre and set it ablaze. The Battle at Aquae Sextiae was a costly one for the Germanic tribes. The Romans suffered 1,000 casualties, while the Ambrones suffered 40,000 killed and wounded and 20,000 captured.

In the early 5th century a Christian priest and historian named Saint Jerome gained access to some fresh material on the battle and its aftermath. Based on his material, he described how 300 captured Teutone women killed their children and committed suicide after their appeals to become temple priestesses to the goddesses Ceres and Venus were denied by Roman officials.

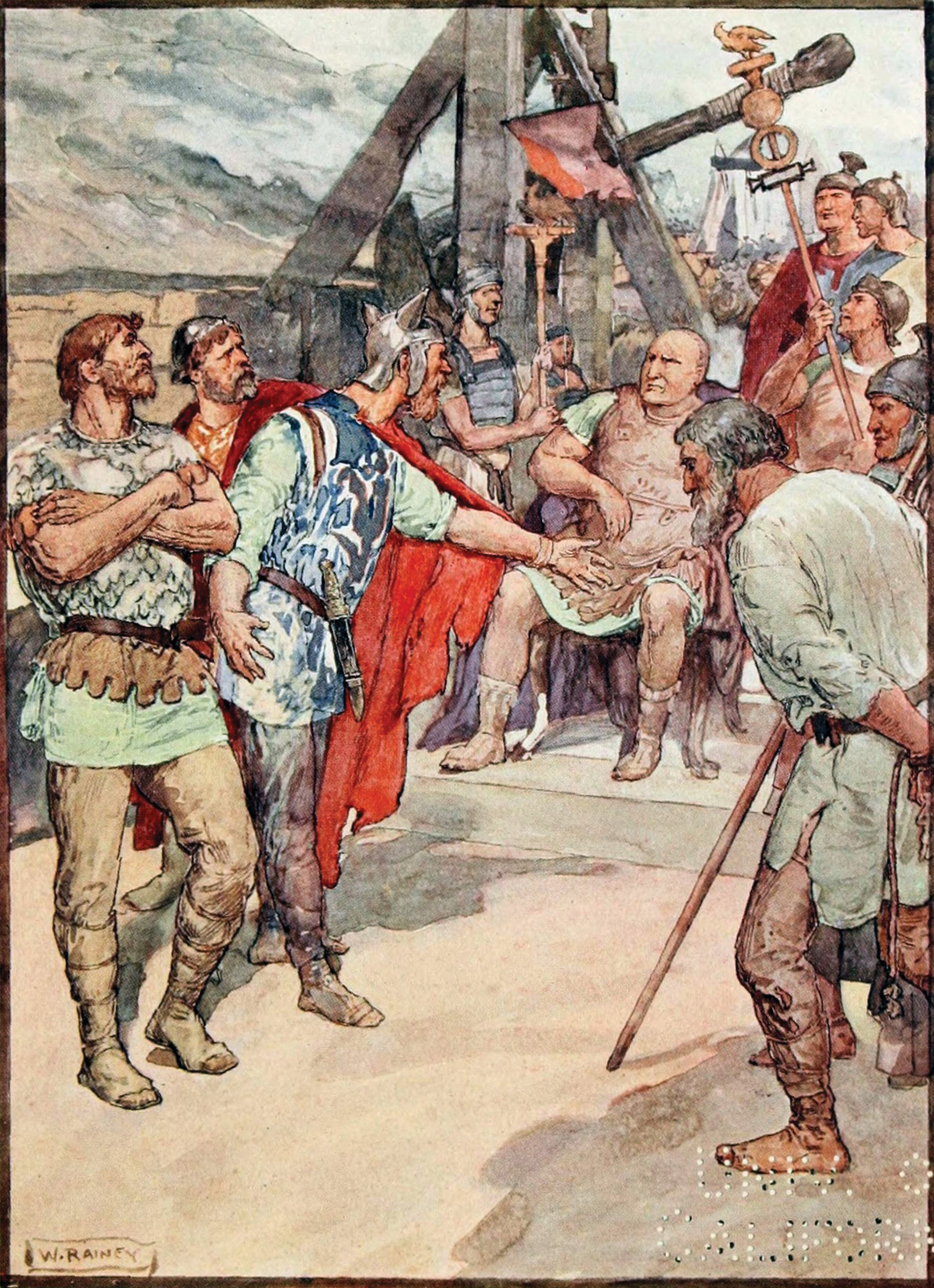

Teutobad managed to escape only to be captured shortly afterward by a Roman-allied tribe who turned him and those with him over to Marius. Almost certainly the Teutone king and any surviving nobles were sent back to Rome for the traditional procession to celebrate their defeat and capture. Afterward, the Romans would have executed them.

Marius returned to Rome as a hero and was elected consul again for 101 bc. Although Marius had defeated the Teutones and the Ambrones, fellow consul Catulus had not prepared his men as well for engaging the Cimbri. His men could not hold back the Cimbri in Rhaetia, and his panicked troops fled south through the Alps to Italy.

Cimbrian King Boiorix, who had played a pivotal role in the defeat of the Romans at Arausio, marched his troops through the 4,500-foot Brenner Pass in the Alps into northern Italy and defeated Catulus on the Adige River. Fortunately for the Romans, the Cimbri did not immediately push deeper into Italy. Despite his defeat, Catulus had somehow managed to keep his army intact.

Having annihilated the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae, Marius marched east to rendezvous with Catulus. In the summer of 101 BC the Cimbri began advancing west along the Po River. In the meantime, Marius and Catulus joined forces at Piacenza. Elected to his fifth consulship, Marius had overall command of the resurgent Roman army. He initiated talks with the Cimbri. They demanded land on which to settle, which Marius flatly refused. He paraded captured Teutone nobles in front of the Cimbri to infuriate them.

Believing they were the superior force, the Cimbri were eager for battle. Although they the Cimbri had 120,000 troops to Marius’s 54,000 men, Roman morale was equal or greater to that of the proud Cimbri. The two sides maneuvered for several days. When his troops marched onto the Raudine Plain near Vercellae, Marius felt comfortable offering battle in that location. In the sanguine battle that followed, the Romans emerged victorious. King Boiorix fell in the slaughter. The victorious Romans massacred the captured Cimbri prisoners and enslaved the Cimbri woman and children. Vercellae thus marked the end of the Cimbri tribe.

Marius’s victories at Aquae Sextiae and Vercellae solidified his reputation as a great Roman general. He used his sterling military reputation to further his political ambitions; however, his controversial political policies ultimately met defeat. He left Italy in 99 BC and traveled through Asia for the next five years.

He returned to Rome on or about 93 bcwhere his controversial political helped bring about the Social War in 91 bc. At the outset of the conflict, he successfully commanded an army against Marsi. Following Publius Sulpicius Rufus’s failure to obtain for him command of the Roman expeditionary army to be sent into Asia Minor in 89 bcagainst Mithridates of Pontus, Marius sailed to North Africa the following year to escape Sulla’s vengeance. But Marius returned to Italy in 87 bcand joined forces with his ally, Lucius Cornelius Cinna. The two generals captured Rome and massacred their political opponents. Marius was then elected in 86 bcto an unprecedented seventh term as consul. He died 13 days later.

Marius is perhaps best remembered today for having transformed the Roman army from a citizen militia to a professional army loyal to its leaders rather than to Rome. His stunning victory at Aquae Sextiae was tangible proof of his tactical genius. Through his defeat of the Cimbri and Teutones, he restored Rome’s military supremacy in Western Europe.