By Jon Diamond

Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army, comprising the U.S. VI and British X Corps, headed north from the Salerno battlefield in September 1943, German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander of Army Group C in southern Italy, implemented new defensive tactics and fortifications.

These were to be more effective at delaying an Allied advance than the panzer counterattacks that had transpired during the invasion of the Italian mainland. After the German withdrawal from Salerno to north of Naples, the stated aim of General Sir Harold Alexander’s Allied 15th Army Group, which included Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth British Army, was the destruction of General Heinrich von Vietinghoff’s Tenth Army south of Rome—not simply the capture of the “Eternal City.”

Geopolitically, Rome’s seizure, to some like British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, would show the Soviets that the Anglo-American alliance was fighting the Germans on a “second front.” Strategically, the Allied Italian campaign would also prevent Kesselring from transferring divisions to France to defend against the Allies’ anticipated cross-Channel invasion.

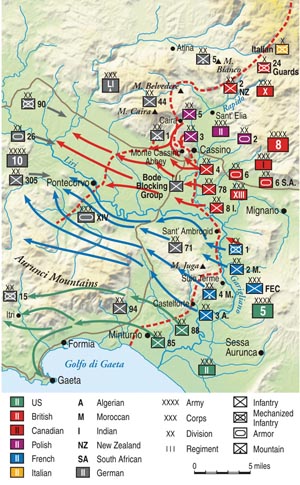

However, geographically, the Allies had to move into the Liri Valley for the thrust to Rome. To thwart an Allied armored advance on Rome, Kesselring wanted Alexander’s divisions to “break their teeth” on his now completed Gustav Line—notably at Monte Cassino with its 6th-century Benedictine abbey atop Monastery Hill, which guarded the entrance to the Liri Valley.

The Gustav Line spanned the Italian peninsula’s narrowest point for roughly 100 miles—from where the Garigliano River flows into the Tyrrhenian Sea extending east through Apennine Mountains to the Adriatic coast.

As Clark’s Fifth Army moved north of the Volturno River in mid-October, the Germans demonstrated continued expertise, honed during the invasion of Sicily, at erecting fortifications and using terrain to delay the Allied movement along the entire front. German automatic-weapons bunkers in mutually supporting locations, as well as mortar pits buried deeply within the rock formations, covered every Allied advance route. German minefields were sown on roads and trails as well as in the valleys and gullies between the mountains.

When the Allies contested German forces in Italian towns and villages, they encountered a different element of enemy defense. Stone houses were transformed into small forts requiring both indirect- and direct-fire artillery and tanks to reduce them. Street fighting became a necessity. Booby traps and mines were ubiquitous delaying tactics in all of these village strongpoints.

In addition to an orderly withdrawal, the Germans destroyed almost every major bridge. This compelled the Allies to ford a series of rivers and streams and build temporary Bailey and treadway bridges under harassing enemy fire.

Mines also dotted the riverbanks. For example, the Germans placed 24,000 mines along the Garigliano at the western end of the Gustav Line, and German engineers diverted waterways to create flooded areas to delay the Allies. With some rivers at flood stage or above, the Allies used flimsy assault boats for waterway crossing as there was no time for temporary bridging.

During the campaign’s mountain warfare south of Rome, control of the heights above determined which combatant was to dominate the valley below. German defensive positions atop mountain peaks were “force multipliers” for Kesselring as well as providing German forward observation posts from which every Allied movement during daylight hours could be targeted.

Thus, much of Fifth Army’s advances had to be made under the cover of darkness or smoke. German howitzers and long-range guns, often self-propelled and well-defiladed behind protecting crests, reached nearly every area held by Allied troops and placed them under near constant harassing shellfire. Each heavily defended mountain would have to be captured, each valley below cleared, and the process repeated.

Exploiting the rugged terrain, the Germans used well-chosen strongpoints to slow the numerically superior Allied forces almost to a standstill north of the Volturno River to the approaches of the Gustav Line. Kesselring proved to be a master at moving his forces along interior lines from one threatened position to another to repeatedly stop an Allied thrust.

Without a suitable road network in the Italian mountains, the Allies resorted to manhandling and using sure-footed pack mules as primary methods for resupply. This was a major Allied logistical hurdle, especially north of the town of Cassino and the monastery.

This German fortification zone incorporated some of the best defensive terrain features available. No single key position presented an opportunity for an Allied coup de main that could break the entire system.

Rugged mountainous terrain led up to Cassino and the Gustav Line. The 5,000-foot sparsely inhabited Monte Cairo massif, with its lower heights ranging from 1,500 to 3,000 feet, was the Liri Valley’s northern shoulder and ran southeast to 1,700-foot Monte Cassino, which is situated along the western banks of the Rapido and Gari Rivers guarding the valley’s entrance.

The Monte Cairo massif was almost devoid of natural routes of communication for a Fifth Army advance. Only two tortuous and narrow roads traversed this desolate landscape. The first one ran to Sant’ Elia Fiumerapido, north of Cassino, while the second one coursed from where the Rapido made a northeastward bend to a mountainous area between Colle Belvedere and Monte Cifalco, then northwestward to Atina.

Fifth Army troops that attempted to debouch into the Rapido Valley also faced two isolated hills—Montes Trocchio and Porchia at 1,400 and 800 feet, respectively. Both of these smaller heights were directly on the approach to Cassino and flanked the plain leading across the Rapido River into the Liri Valley. Furthermore, the German diversion of the river upstream had turned the approaches to the Rapido opposite Cassino to a sea of mud.

From the high ground on the far bank of the Rapido, the Germans observed and could bring fire on the entire area below. Any small-scale Fifth Army attack across the Rapido was likely to fail as long as Monte Cassino, along with the hill country to the north and west, was in German possession. Here the Germans had well-sighted artillery and mortar emplacements poised to bring fire on the entire Allied offensive area and large parts of the rear area of U.S. II Corps near Montes Trocchio and Porchia.

The Gari River began just south of the town of Cassino and met the Rapido River near Sant’ Angelo. The Rapido, roughly 25 to 50 feet wide with steep banks, had a swift-flowing current and coursed from its mountainous origin north of Monte Cassino, weaving in a southerly direction in front of the heavily fortified town of Cassino, making it a formidable natural obstacle.

Kesselring had supplemented this Rapido River zone with interlocking minefields, machine-gun pillboxes, concrete and steel entrenchments for field ordnance, barbed wire, and rifle pits.

Several miles downstream, the Rapido flowed into the Liri River near Sant’ Ambroglio with the confluence of both waterways becoming the Garigliano River at the southern end of the Liri Valley. Here, the Rapido-Garigliano floodplain constituted one obstacle to the advancing Fifth Army while another five-mile-wide floodplain was situated on the eastern side of the Garigliano’s mouth, which made an attack across this area hazardous.

Steep upland mountains, which bordered the western bank of the Garigliano, ended on the southern slopes of Monte Maio and then continued south of the village of Castelforte along high ground north of Minturno to the Tyrrhenian Sea, constituting the western end of the Gustav Line.

Throughout a horrific autumn campaign, marked by violent mountain combat and disastrous river crossings, Clark’s Fifth Army slowly forced the German Tenth Army’s XIV Panzer Corps, under General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, into the Gustav Line’s defenses and across the Rapido River. British Eighth Army’s XIII and V Corps divisions formed north of the Sangro and Moro Rivers after the gruesome battles for Orsogna and Ortona. The Adriatic sector became static south of the Rome Line.

But it was Monte Cassino that was, indeed, the Gustav Line’s centerpiece. Kesselring’s defense of this sector, from late January to mid-May 1944, denied a swift Allied entry into the Liri Valley and access to Highway 6 for an advance to Rome. During these four months, the ordeal of the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Battles for Cassino transpired. Despite all his advantages, Kesselring realized that the Gustav Line could not contain the Fifth and Eighth Armies south of Rome indefinitely; however, he reasoned that a delay of several months to an Allied breakthrough along the Gustav Line would forestall the strategically more important crossing of the Northern Apennines’ Gothic Line into the Po Valley and northern Italy, which constituted the industrial and agricultural centers of Italy.

Toward the end of December 1943, experienced troop strength changed within Fifth Army. The men of the 45th U.S. “Thunderbird” Division, veterans of the Sicily and Salerno invasions, were relieved by the French Expeditionary Corps’ (FEC) 3rd Algerian Division because the 45th, along with the combat-hardened 3rd U.S. Division, were readying for the amphibious end-run assault north of the Gustav Line at Anzio—Operation Shingle, scheduled for January 22, 1944.

Shingle’s aim was to force a German withdrawal from the Gustav Line by inserting the U.S. VI Corps behind the Tenth Army. Once the Germans abandoned the Gustav Line, it was assumed, the Allies would be able to make a rapid advance to Rome.

Thus, in January 1944, the U.S. II Corps’ 34th and 36th U.S. Divisions, along with the FEC’s 2nd Moroccan and 3rd Algerian Divisions, became the Fifth Army’s assault divisions to attack across the Rapido as it curved north of Cassino.

On January 16, six days before Shingle was to commence, General Geoffrey Keyes’ U.S. II Corps had secured Monte Trocchio, the last high ground before the Rapido River, southwest of Cassino. This vantage point gave the Allies a commanding view of the positions held by the German 44th Infantry and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions.

Clark’s plan was to initially assault the Gustav Line by throwing the U.S. II Corps and British X Corps into the attack, crossing the fast-flowing waters of the Rapido, Garigliano, and Liri Rivers, and then breaking into the Liri Valley from the south. British General Richard McCreery’s X Corps had more than a month to rest and to reconnoiter the Garigliano crossings. The 5th British Division, brought in from the Adriatic sector on January 15, took up positions on the Tyrrhenian coast and joined the 56th and 46th Divisions in the center and far right of X Corps’ sector, respectively.

On the evening of January 17, X Corps artillery fired across the Garigliano while Allied ships in the Gulf of Gaeta pounded German positions to the rear of the northern bank, but the XIV Panzer Corps did not recoil. The 5th British Division crossed the river at the narrow estuary in landing craft around the Garigliano’s mouth and then moved on Minturno and Tufo at the entrance to the Ausente River Valley.

The 56th British Division also successfully crossed the Garigliano and attacked through German positions toward Castelforte and the foothills of the Aurunci Mountains. Next, the 46th British Division attempted the river crossing on either side of Sant’ Ambrogio, just to the south of the confluence of the three rivers, where it would serve as the left flank of the U.S. II Corps.

But the 46th’s river assault fared poorly, was turned back by heavy enemy fire, and had to be postponed until the next day. By the morning of January 18, all of the 5th and 56th British Divisions’ attacking formations were across the river and had established bridgeheads after compelling a retreat of elements of the German 94th Infantry Division in the foothills of the northern bank. The 46th Division was moved south of the abortive crossing of Sant’ Ambrogio to join the British 5th and 56th Divisions and defend against enemy counterattacks.

On January 20, Clark ordered two of Maj. Gen. Fred Walker’s veteran 36th “Texas” Division’s regiments (the 141st and 143rd) to cross the Rapido south of Cassino to keep the Germans occupied on the Gustav Line and prevent them from being transferred to Anzio once Shingle got underway. Clark also wanted his army to break into the Liri Valley toward Frosinone so it could join up with the Anzio invasion force moving inland.

Under the cover of darkness, the “Texas” Division also brought forward assault boats, bridging equipment, ammunition, and smoke pots––the latter to help mask the upcoming river crossing from the overlooking German positions.

However, by the night of the 20th, American attempts to clear mines and mark paths to the river’s edge were inadequate at best. From January 20-22, the 36th’s 141st and 143rd Infantry Regiments tried to cross the Rapido River to force an entrance into the Liri Valley without success. Casualties were disastrous. By the morning of the 21st, only a handful of platoons from the 143rd had managed to cross to the south of Sant’Angelo and were tenuously holding onto a portion of the river’s western bank.

After a German counterattack, the assaulting elements of the regiment’s 1st Battalion had to retreat back across the river under enemy fire. To the north of Sant’ Angelo, two companies from the 36th’s 141st Infantry established a small bridgehead, but it, too, proved impossible to strongly reinforce, as only six rifle companies made it to the west bank. Eventually, only a few dozen survivors of these companies of the 141st would withdraw back to the eastern side of the Rapido.

As one historian has written, “When General Clark received the news of this failure, he insisted that the Texans try again, supported by tanks,” ordering Keyes to resume the attack with the surviving battalions of the 143rd Infantry Regiment. At 4 pm on January 21, the 143rd, under a heavy artillery screen, made a second river crossing attempt.

A total of five infantry companies comprised the American bridgehead on the western side of the Rapido River; however, before dawn the next day this salient was eliminated by a German counterattack.

The Fifth Army’s initial assault on the Gustav Line and access to the Liri Valley south of Cassino, after initial optimism at Clark’s headquarters, came to a halt on January 22. General Walker noted, “Yesterday two regiments of this division were wrecked on the west bank of the Rapido. Thank the Lord, General Keyes finally changed his mind and authorized me to call off the attack….”

The “wreckage” was severe, with American losses in the Rapido crossing amounting to more than 140 dead, roughly 700 wounded, and almost 900 missing.

Operation Shingle, launched on the 22nd, caught the Germans by surprise, but VI Corps commander John Lucas feared a German counterattack, as had earlier occurred at Salerno, and kept his forces close to the beachhead. His reluctance to aggressively push inland allowed Kesselring time to bottle up the Allies by bringing in enough fresh units without weakening his Gustav Line.

The failed crossing of the Rapido on January 20-22 also changed the axis of the FEC’s advance. Two of General Alphonse Juin’s four divisions, the 2nd Moroccan and 3rd Algerian, began their offensive to the north of the 34th U.S. Division on January 24.

The Moroccans breached the Gustav Line near Monte Santa Croce, while the Algerians crossed the Rapido River in the vicinity of Sant’ Elia Fiumerapido and turned southwest to parallel the 34th’s movements, advancing on Colle Belvedere and then Monte Abate, in the process severing the road to Atina to the north on January 26.

At Monte Abate, the FEC forces were soon counterattacked by elements of the German 44th Infantry Division, which evicted the Tunisian 4th Rifle Regiment from the mountain and kept Juin from retaking the height.

Keyes reinforced the Algerians with the 36th Division’s 142nd Infantry Regiment (which had not participated in the Rapido crossing debacle days before) to advance southward on Monte Cassino from the Colle Belvedere area. But from their elevated observation posts German gunners could direct artillery and mortar fire onto any Allied approach toward Monte Cassino.

Keyes’ exhausted, combat-depleted Fifth Army’s II Corps now needed Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese’s Eighth Army (Montgomery had just departed for England) to assist with the stalled Gustav Line offensive. The combat-experienced 2nd New Zealand Division was brought west across the Apennines and combined with Maj. Gen. Francis Tuker’s veteran 4th Indian Division to form the II New Zealand Corps under Lt. Gen. Bernard Freyberg on January 30.

Changes were also made in II Corps. After the bloody repulse of the “Texas” Division at the Rapido, Maj. Gen. Charles Ryder’s 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division, with the 36th’s 142nd Regiment attached, was brought up and prepared to attack across the river north of Cassino.

The 34th Division’s attack commenced on January 24 near the bend of the waterway’s course, with its 133rd and 135th Infantry Regiments advancing into flooded terrain. But extensive minefields and interlocking machine-gun fire necessitated a withdrawal.

However, on January 26-27, the 34th’s 168th Infantry Regiment, supported by a handful of tanks from the 756th U.S. Tank Battalion, managed to establish a bridgehead across the Rapido opposite Caira farther to the north of the 133rd and 135th Regiments, and captured two small hills and enemy bunkers.

Over the next few days, tank-infantry cooperation enabled the 34th to take Caira, forcing Kesselring to bring in his 90th Panzergrenadier and 1st Parachute Divisions from the Adriatic coast to slow the 34th’s penetration. The 135th Infantry Regiment then passed through the 168th to advance up the hills behind the Abbey and reach Highway 6.

Slow progress was made by the Allies in the northern outskirts of Cassino during the first few days of February 1944 amid logistically challenged combat in the Monte Cairo massif, as the 34th’s regiments tried to outflank German defenses at Cassino. On February 1, the 133rd drove west toward Cassino and cleared the Monte Villa Barracks.

The 135th also seized the commanding height of Monte Castellone, just to Caira’s southwest. The next day, the 34th, accompanied by American tanks, began the attack from the north of the town but met with fierce resistance.

Fortified masonry houses served as bunkers, along with antitank gun positions along the Caruso Road’s intersections, which stopped the American advance.

Four days later, elements of the 135th Infantry Regiment, despite withering fire, captured an area near Hill 593, which overlooked the abbey, 1,000 yards away. The 168th came to within several hundred yards of Mount Calvary, a tactical key point overlooking Monte Cassino, which was to change hands among the combatants during the first few days of February as fresh panzergrenadier and paratroop reinforcements launched their counterattacks.

During the night of February 5-6, the 168th directly assaulted Monte Cassino via a deep gorge and, although some Germans were captured from a Monastery Hill cave, the Red Bulls had to pull back because of heavy German fire.

Resupply of the 34th’s positions was difficult as combat exhaustion and casualties mounted. The remaining battalions of the 34th Division were ineffective in a renewed assault on February 11 to seize Monastery Hill and the town of Cassino as German artillery and mortars stopped them within a few hundred yards of their rocky positions.

The American attack was ebbing. By February 12, some areas to the north of the town were gained by the Americans as a small portion of the Gustav Line was pierced, but there was no general advance.

From February 12-14, after three weeks of constant fighting, elements of the II NZ Corps’ 4th Indian Division took over the 34th U.S. Division’s positions near Hill 593 and other heights overlooking Cassino from the north. Only 25 percent of the combined 3,200-man initial strength of the 34th’s 135th and 168th Infantry Regiments now remained.

If the reinforced 34th Division and the FEC could succeed in their attack, the 4th Indian and 2nd NZ Divisions were to move through them and exploit the breakthrough. However, Freyberg’s NZ and Indian troops were held in reserve rather than committed to the tail end of the hard-pressed Allied mountain attack north of the town and monastery during the First Battle of Cassino.

These battle-hardened Eighth Army troops instead served only to evacuate the dead and wounded American troops and take over the hard-fought, costly ground that they had won. The First Battle of Cassino ended with the Germans still in possession of most of the town, the monastery, and the surrounding heights just to the west.

After the unsuccessful U.S. II Corps attempts to break through the Gustav Line north and south of Cassino, Clark deployed the II NZ Corps to, perhaps belatedly, follow up on the ground gained by the 34th U.S. Division’s three attacking regiments and the attached 142nd Infantry from the 36th Division. American lines in the vicinity of Snakeshead Ridge, northwest of the abbey and to the north of the town, were held by the remnants of these four U.S. II Corps regiments.

Both Tuker and Freyberg had convinced the Allied chain of command—Alexander, Clark, and Field Marshal Henry Wilson, commander of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO)—that the monastery’s obliteration was a prerequisite for a successful attack, as they (wrongly) believed the Germans were overlooking their moves from within the abbey. Clark was opposed, but was overruled.

Unknown to the Allies, the Germans weren’t inside the monastery, but they did have positions ringing it; German XIV Corps commanding general Senger und Etterlin forbade the Abbey’s use, except for the wounded.

After dropping leaflets notifying anyone in the monastery that it was going to be bombed, the Second Battle of Cassino, Operation Avenger, began on February 15 with a massive four-hour air raid by Allied medium and heavy bombers, followed by an artillery bombardment. Advanced units of the 4th Indian Division’s 7th Brigade, receiving little warning of the aerial assault, incurred some “friendly fire” casualties.

The monastery’s outer walls were destroyed by the bombardment of February 15, while the west wing and cellars remained intact. After sundown, the Germans transformed the ruins into a defensive bastion.

Freyberg’s unimaginative plan was a continuation of Cassino’s first battle, and he gave it only a 50 percent chance of success. Its scope was extremely small in terms of the size of the forces deployed. The 4th Indian Division was to attack in battalion strength southward past the American positions, which they relieved on February 12, to seize Hills 593, 569, 444, and 516 as a prelude to assaulting the monastery and then advance down the hill and cut the road to the town of Cassino.

The 28th Maori Battalion of the 2nd NZ Division was to separately cross the Rapido River in the vicinity of the town’s railway station, to ultimately rendezvous with the anticipated victorious Indians, thereby gaining an entry into the Liri Valley via Highway 6.

But two separate attacks by the 7th Indian Brigade failed to capture Hill 593 on February 15-16. Other elements of the 4th Indian Division continued the attack on the monastery on the 17th and 18th; however, with units of the German 1st Parachute Division situated behind minefields and barbed wire, the Indians lost almost 650 officers and men killed, wounded, or missing.

Using bridges and causeways that sappers had repaired under fire, two companies of Maoris crossed the Rapido-soaked fields and fought their way into Cassino’s railway station on February 17.

Despite an extensive smokescreen to mask the engineers’ work from German observers, crucial bridges that would support Allied armor were not repaired, limiting the attack to only a Maori battalion-sized infantry assault. The customary counterattack with some panzers ensued, and the Maoris withdrew, their ammunition exhausted. The short-lived Second Battle for Cassino ended like the first––with the Germans in command of the town and now occupying the ruins of the monastery atop Monte Cassino.

The Third Battle of Cassino, Operation Dickens, began on March 15, 1944. Freyberg realized that it was vital to attack the town of Cassino and monastery from multiple directions and get both tanks and infantry assaulting simultaneously.

He now believed that assaults solely from Snakeshead Ridge and the various nearby hills northwest of Monte Cassino would fail, thus an Indian effort to capture the heights below the monastery was essential in conjunction with the New Zealanders’ assault on the town.

If they could capture the town, the New Zealanders were to dislodge the Germans along the heights by outflanking them in southward and westward movements to seize Cassino town and, perhaps, a portion of Highway 6. The Kiwi advances were to facilitate the Indian units in reaching their elevated points to capture the monastery and, perhaps, seal the German escape into the Liri Valley.

In Freyberg’s final planning for Dickens, the town of Cassino was also to be bombed during the morning of March 15 by 500 Allied heavy and medium bombers, followed by a creeping artillery barrage behind which the New Zealanders would launch their ground attack.

The plan of attack was ambitious; two infantry companies and an armored squadron would hit the northern part of town and advance to the Hotel Continental. Another infantry company would seize Castle Hill (Hill 193) and then be relieved by part of the 5th Indian Brigade, 4th Indian Division, which would then continue on to assault its next objective, Hill 165.

Castle Hill was to serve as an advance point for other battalion-sized units from the 5th Indian Brigade to assault the hillsides above the town. Then elements of the NZ 24th and 26th Battalions, 6th NZ Infantry Brigade, with Allied tanks, were to attack the town from the east.

The bombing of Cassino on the morning of March 15 was stupendous. During the spectacle, one British soldier said, “After a few minutes I felt like shouting, ‘That’s enough!’ but it went on and on until our eardrums were bursting and our senses befuddled.”

The Germans on the receiving end were even more shocked. One soldier recalled, “This time we were in the midst of it. The air vibrated, and it was as if a huge hand was shaking the town.”

Another German wrote in his diary, “Today hell is let loose at Cassino.” An awe-struck American officer said, “We have fumigated Cassino,” believing no one was left alive.

The Allied bombing and barrage leveled the town, creating huge piles of rubble and up to 60-foot-deep craters that were impassable to tanks. However, there were survivors, and the host of ruins became fortified defensive positions for them. Smoke and dust clouded the ruins as snipers killed runners and signalers to disrupt communications.

On that day, a platoon of Company D of the NZ 25th Battalion captured Hill 165, only to take fire from Castle Hill (Hill 193) on one side and from Hill 236 above them. Two other platoons from Company D took the castle; however, the 5th Indian Brigade’s men did not reach the castle until midnight, several hours after the Kiwis’ attack. It would not be until early on March 16 that the Indians reinforced Hill 165.

Two other companies of the NZ 25th Battalion moved south toward the Hotel Continental while receiving enemy sniper, machine-gun, and Nebelwerfer fire from the town and nearby hills, which delayed their advance.

There were insufficient numbers of Kiwi infantry to press the attack, as the NZ 6th Brigade’s 24th and 26th Battalions were delayed in their assault from the east. Even the German ground commanders at Cassino were perplexed by such massive firepower being employed only to be followed by a paltry infantry assault of a few battalions and tanks.

On March 16, almost 24 hours behind schedule, other elements of the 5th Indian Brigade went into action. Two companies of the 1/6th Rajputana Rifles attempted to attack Hill 236, but they were driven back to the castle, while two other companies from this battalion were lost to German Nebelwerfer fire and had not secured the intervening Hills 236 and 202 to cover the 1/9th Gurkha Rifles’ attack on Hangman’s Hill (Hill 435).

Nonetheless, platoon-sized elements of the 1/9th Gurkha Rifles ascended Hangman’s Hill and clambered to within 300 yards of the monastery’s walls under the cover of darkness. The attack stalled, and they were to remain there in a precarious situation, reinforced only by the continued gradual arrival of other small units from this battalion and receiving supplies only by airdrop or manhandling them up the height.

On March 16, Kesselring transferred elements of the 4th Parachute Regiment to Cassino from nearby Colle Sant’ Angelo located west of Snakeshead Ridge and north of Highway 6.

The weather also changed that evening as rain began to fall. The next day saw the Third Battle for Cassino end in stagnation as terrain, debris, and a need for low casualties forced both the Indians and New Zealanders to fight in small groups with limited armored support.

Fortunately, by March 17 the railway station was occupied by units from the NZ 26th Battalion that had advanced southward against a tenacious defense put up by elements of the German 2nd Parachute Battalion. On the 18th, other units from the NZ 25th Battalion, which had kept moving south from Hill 165, failed to capture the Hotel Continental, but the railway station and other parts of Cassino were to remain in Kiwi control despite strong German counterattacks.

On March 18-19, German parachutists attacked the 5th Indian Brigade atop Castle Hill as they were deploying to reinforce their Gurkha comrades on Hangman’s Hill. Ferocious close-quarter combat ensued, with the Germans eventually withdrawing.

A converging Allied attack on Monastery Hill was to be launched from two disparate locales on the morning of March 19. From Hangman’s Hill, elements of the 1/9th Gurkha Rifles were to comprise one salient of the assault. However, with persistent and determined German small-arms and mortar fire from parachutists above them, and without adequate 4th Indian Division reinforcements, the attack was called off.

A second, simultaneous assault on Monastery Hill from the west was launched with 19 M4 medium Sherman and 21 M3 Stuart light tanks assembled from the U.S. 760th Tank Battalion, 20th NZ Armored Brigade, and a 7th Indian Brigade Reconnaissance Squadron.

This armored element advanced down the Cavendish Road to the west of Snakeshead Ridge near the Albaneta Farm. The Germans were initially stunned by this bold thrust; however, the opportunity created by the Allied armored attack was halted due to an absence of accompanying infantry to support the tanks, poor local Allied leadership, and enemy minefields that were hastily sown but still managed to destroy almost a score of tanks.

By the close of March 19, both New Zealanders and Germans were still wrestling for control of Cassino town. The 28th Maori Battalion of the 5th NZ Brigade attacked from the east but again failed to capture the Hotel Continental and the Hotel des Roses. Four more days of limited but fierce combat at separate locales continued until Alexander called off further II NZ Corps attacks on March 23.

Freyberg’s troops solidified their limited gains within the ruins of the town of Cassino, while the Gurkha and Rajputana Rifles abandoned their blood-soaked positions on Hangman’s Hill and the intervening territory between Hills 236 and 202 without any further casualties on the night of the 24th. The German paratroopers, however, had also been decimated out of proportion to the scope of the fighting.

With a compelling need for a new attack scheme to reverse the three-month-long string of failed Allied efforts to break the Gustav Line, General Alexander began his operational planning for a May 1944 offensive called Operation Diadem, of which the battle for Cassino would become a finale. Coordinated with Operation Buffalo, a plan for VI Corps to break out of the Anzio beachhead, the Allies were hopeful that this time they would succeed on both fronts.

The Fifth and Eighth Armies were to attack the Gustav Line on May 11 under Alexander’s unified command and his planned three-to-one numerical superiority in infantry. It was to be a return to the “set-piece” British-style offensive.

Set-piece offensives involved the profligate expenditure of artillery. During the run-up to Diadem, Fifth Army guns fired 170,000 rounds within four hours. A Polish lieutenant said, “Apart from 1,100 pieces of artillery, there were the mortars and antitank guns blazing away—the noise deafened us.”

After recovering from battle wounds sustained while commanding 7th Armoured Division in North Africa, Lt. Gen. A.F. “John” Harding, an experienced staff officer and desert field commander in Montgomery’s Eighth Army, arrived in the MTO on New Year’s Day 1944 to become Alexander’s chief of staff.

Harding saw that a major offensive on the Gustav Line along the Cassino-Garigliano front was more likely to strategically break the months-long deadlock than on the Adriatic side, so he recommended that Eighth Army’s commanding general Leese redeploy British Lt. Gen. Sidney Kirkman’s XIII Corps west across the Central Apennines to occupy an area from the Liri River up to the south of Cassino on the eastern bank of the Rapido River.

Kirkman’s XIII Corps was composed of 8th Indian and British 4th Infantry Divisions in line for the attack, with the British 78th Infantry and 6th Armoured Divisions in reserve on the left flank of its zone south of Cassino. To the right of XIII Corps and facing Monte Cassino and extending north opposite the Monte Cairo massif was Lt. Gen. Wladyslaw Anders’ Polish II Corps’ 3rd Carpathian Rifles and 5th Kresowa Divisions, with the Polish 2nd Armoured Brigade in support.

McCreery’s British X Corps had been transferred from the Garigliano sector to the northern Rapido zone—a desolate, virtually impassable mountainous wilderness area along the Central Apennines—to become the right flank for the Polish II Corps.

Freyberg’s II NZ Corps divisions, which were out of the line for rest and refitting, were ordered back into the new British X Corps sector along with a division-sized formation of Italian troops now fighting for the Allies; Lt. Gen. Charles Allfrey’s British V Corps remained on the Adriatic coast.

Alexander shifted Clark’s U.S. Fifth Army, composed of the U.S. II Corps and FEC, to the southern end of the Gustav Line. From the Tyrrhenian seacoast Keyes commanded II Corps’ newly arrived 85th and 88th U.S. Infantry Divisions with the now four FEC divisions (Algerian 3rd Infantry, Moroccan 4th Mountain and 2nd Infantry, and French 1st Motorized) on their right flank facing Castelforte, Montes Maio and Faito, as well as the Ausente River Valley, which ran parallel to the Castelforte-Ausonia road. Juin’s FEC would strike into the mountains forming the southern wall of the Liri Valley.

Lieutenant General E.L.M. Burns’ I Canadian Corps, with its 5th Armoured Division and 1st Independent Canadian Armoured Brigade supporting the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, along with the 6th South African Armoured Division, was held in reserve, ready to exploit a breakthrough into the Liri Valley.

Alexander and Harding wanted to wait until mid-May to launch the Gustav Line offensive, as drier weather and clearer skies would amplify the Allied advantages in armor and air power. But Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of France at Normandy, was fast approaching; Clark and Churchill both desperately wanted to take Rome before Overlord wiped the Italian campaign off the front pages.

Strategically, Operation Diadem was designed to engage German divisions that might be moved to meet the upcoming Allied invasion at Normandy. Also, it was Alexander and Harding’s intent to destroy the German Tenth Army along the Gustav Line, not merely push it back to the next of Kesselring’s defensive positions nor simply capture Rome.

Unlike the Second and Third Battles for Cassino, where only companies and battalions were deployed, the two British generals planned to initially hurl two Allied corps—the British XIII and Polish II—against the Cassino fortifications along seven to eight miles of front extending from the foot of Monte Cassino to the Liri River, the locus of previous failed Rapido and Garigliano River assaults. This attack route for Diadem was selected as the only portion of the Gustav Line against which Allied armor of up to 2,000 tanks could be unleashed in strength.

Vietinghoff’s German Tenth Army had to hold the sector extending from Monte Cassino south to the Liri River to prevent its bisection. Eighth Army’s divisions were to be pitted against tenacious German parachutists amid the piles of stone rubble defenses in Cassino. The Allied front was directly observed and covered by German artillery and mortars.

Once they broke through the Gustav Line, Frosinone and Valmontone to the northwest, both within the Liri Valley along Highway 6, were the main goals of Alexander and Harding. The British commanders believed that an Allied linkup with VI Corps, now under Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, breaking out of the Anzio beachhead, and the formations attacking through the Liri Valley at Valmontone had the potential of destroying the entire German Tenth Army.

The British XIII Corps was to batter the German defenses and force a Rapido River crossing at Sant’ Angelo under artillery bombardment. The Polish II Corps was assigned the capture the heights of Monte Cassino and then move on to Piedimonte San Germano, the northern anchor of the Hitler Line, several miles beyond the Gustav Line’s defenses. After breeching the Gustav Line just to the south of Cassino, Burns’ I Canadian Corps was to enter the Liri Valley and advance onto the Hitler Line (also known as the Senger, Dora, or Orange Line) defenses, with British XIII Corps on its right flank.

Facing the Allies were the German XIV Corps’ 94th, 71st, and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions. The two divisions of the U.S. II Corps would go up against the German 94th Division, while the FEC Corps, comprising four divisions including more than 7,000 irregular mountain troops from the Maghreb, was to be pitted against the German 71st Division.

The Wehrmacht’s LI Mountain Corps, under General Valentin Feuerstein, faced the British X, Polish II, and British XIII Corps and defended the northern half of the Liri Valley up to the southern escarpment between Monte Cassino and Piedimonte San Germano.

This mountain corps was composed of the 44th Division on the southern bank of the Liri River; battalions of the 1st Parachute Division in the town of Cassino and within the monastery; the 5th Mountain Division; and elements of the 114th Jäger Division to the north of the paratroops. Group Hauke, a corps-sized formation formed by the 334th and 305th Infantry Divisions, constituted the German Tenth Army’s left flank extending toward the Adriatic seacoast guarding against the British V Corps.

At 11:45 pm on May 11, the British XIII Corps’ attack by leading elements of its 8th Indian and 4th British Infantry Divisions initially appeared to be yet another failed Rapido River assault as the swift waterways’ current capsized and swept assault boats downstream. However, other attacking battalions were able to make it across to form a limited bridgehead.

Further advance was stalled by a lack of heavy weapons or armor support against a deep and continuous network of German field and concrete fortifications and minefields. Although the 8th Indian Division had two bridges spanning the Rapido near Sant’ Angelo by morning on May 12, insufficient tank-bearing bridges had been built due to accurate enemy artillery and gunfire driving the engineers into cover.

Kesselring, recognizing that his Tenth Army’s defenses were penetrated near Sant’ Angelo, fed in only piecemeal reinforcements to contest the British bridgehead. It was not until 5 am on May 13 that the 4th British Division was able to erect a bridge.

The next day Leese committed the 78th British Division from reserve to reinforce the 2,000-yard-deep bridgehead despite vehicle congestion and muddy terrain. After three days of unrelenting combat, Kirkman’s XIII Corps was still unable to penetrate the Gustav Line south of Cassino, so Leese ordered the I Canadian Corps to take over the front of the 8th Indian Division on May 15.

The Polish II Corps’ two infantry divisions had also struggled for two weeks on the Monte Cassino-Monte Cairo massif before Diadem’s start. The rocky ground forced the Poles to burrow into the protection of small stone sangars with any movement drawing German fire. The Polish assault battalions had begun their attack at 1 am on May 12, incurring a casualty rate of 20 percent, and were tardy seizing their objectives.

Without proper reconnaissance, there had been no coordinated preliminary artillery bombardment of German positions. Enemy minefields prevented close Polish armor support, causing heavy casualties among the engineers trying to clear them. Finally, the Poles were pitted against the ferocity of the German parachutists.

Within 12 hours of the start of the Polish II Corps assault, the tactical situation had become completely confused, and the attack was temporarily postponed for reorganization. Nonetheless, by May 16, the Poles eliminated several defensive positions in a brutal struggle of attrition.

Along the Tyrrhenian coastal area, the U.S. II Corps attacks at the start of Operation Diadem on May 11-12 emanating from Tufo and Minturno had failed. Near San Maria Infante, a battalion from the 339th Infantry Regiment, 85th Division suffered over 75 percent casualties from German artillery bombardments and a stout 94th Infantry Division defense.

The next three days saw little American progress, but suddenly on May 15, the Germans began withdrawing due to the stunning FEC breakthrough of the Gustav Line from Castelforte to the Liri River and into the barren hilly terrain of the Aurunci Mountains.

The German commanders had deemed the FEC attack zone impassable, but elements of the 2nd Moroccan Division surprised them by advancing four miles within 24 hours of Diadem’s start, taking Monte Maio on May 13. As German forces were thin in this mountainous terrain, FEC units broke through all along this sector.

Elements of the French 1st Motorized Division then arrived on high ground near Sant’ Apollinare and were poised to move into the Liri Valley on May 14. The Germans never recovered from this breakthrough; the Wehrmacht’s 71st Division disintegrated after its flanks were enveloped, causing heavy casualties and 2,000 men captured. The remnants of the 71st withdrew to the Hitler Line on May 14, numbering only 100 combat-effective infantrymen by May 18.

As a result of the FEC success, the U.S. 85th and 88th Divisions progressed nine miles beyond the Garigliano River’s mouth toward Formia against the hard-pressed German 94th Division. On the 15th, Kesselring agreed to a general withdrawal in the Tyrrhenian coastal sector.

On May 17, Polish infantry battalions, under the cover of Allied fighter bomber sorties, again failed to dislodge the Germans from Monte Cassino. Although the German paratroopers continued to fight with fury, the Poles, after being initially halted, renewed their assault along Phantom Ridge and Snakeshead Ridge as the British XIII Corps worked its way behind Monte Cassino. Polish armor then began rolling down Cavendish Road and attacked Albeneta Farm.

Seeing the handwriting on the wall, the German paratroopers pulled out during the night and retreated to the Hitler Line; the Poles had taken the monastery and the heights. The banner of the 12th Podolski Lancers was hoisted above the ruined abbey on the morning of May 18. Fourth British Infantry Division units cleared Cassino town, and sappers, including a South African engineer unit, began clearing Highway 6 of rubble for the movement of Allied armor.

The Poles had suffered heavily: almost 300 officers and more than 3,500 other ranks, with over 800 deaths. But their attack worked.

Meanwhile, U.S. II Corps divisions had taken Gaeta and Itri on May 19, and FEC forces on that day crossed the Itri-Pico Road, which connected Highways 6 and 7, and entered the Ausoni mountain range. The next day, American infantrymen entered Fondi as the French continued their thrust toward Pico on the Hitler Line, the latter threatening to trap the German Tenth Army in the Liri Valley.

Terracina was captured on the 22nd, and three days later a special group of the Allied VI Corps beachhead forces from Anzio finally made contact at Borgo Grappa with troops coming up from the Gustav Line. Clark was there to observe the linkup—and to have his picture taken by Army photographers. The race to Rome could now begin in earnest.

But the Liri Valley’s terrain of thickets, vegetation, and muddy ditches provided excellent German defensive cover, making travel on Highway 6 hazardous. The German defensive order of battle was the depleted 1st Parachute and 90th Panzergrenadier Divisions, with some tanks from the 26th Panzer Division. The strength of the German position in the Liri Valley was in its fortifications, especially the buried Panzer V turrets (Panzerturm) which, with their 75mm long-barreled guns, were Allied tank killers.

After the British XIII Corps initially pierced the Gustav Line, the I Canadian Corps—consisting of the 5th Armoured Division and 1st Independent Canadian Armoured Brigade supporting the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, along with the 6th South African Armoured Division—received orders to advance to the Hitler Line, several miles up the Liri Valley from the Rapido River.

The Canadians had made probing attacks against the Hitler Line on May 19-20, then the 1st Canadian Infantry Division launched its major attack, Operation Chesterfield, on the morning of May 23 at Pontecorvo, supported by Eighth Army’s 700 guns.

The Canadians broke the German defenses in a day’s combat; however, there were steep casualties—900 infantrymen and 80 Royal Tank Regiment crewmen. A followup assault by British XIII Corps the next day broke this defensive belt completely despite counterattacks by the German 26th Panzer and 305th Infantry Divisions.

On May 25, Canadian motorized columns crossed the Melfa River farther up the Liri Valley, while elements of the British 78th and 8th Indian Divisions took Aquino. On May 31, the Canadians captured Frosinone on Highway 6.

A united Allied front was soon established for the drive to Rome, but Mark Clark did everything in his power to keep the British and other Allied troops from taking part in the capture of the city, which took place on June 4—two days before Overlord was launched.

It had been a bitter and costly four-month ordeal to pierce the Gustav Line and seize Monte Cassino, enabling the Allied entry into the Liri Valley; with great sacrifice the Allies did it. But there were still 11 more months of hard fighting in Italy before peace was declared.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments