By Jon Diamond

Brigadier Leslie Andrew, VC, DSO, was born in New Zealand on March 24, 1897. He served his country and the British Empire during both world wars.

Due to an authorized tactical withdrawal that he made as a lieutenant colonel commanding the 22nd New Zealand Battalion defending the Maleme airfield and surrounding perimeter on the island of Crete on May 20, 1941, numerous histories have linked his name and action as, perhaps, the turning point of the entire battle as German paratroopers took over the airfield early on May 21, resulting in the loss of the island to the enemy 11 days later. However, a fresh look at the critical events surrounding Andrew’s “heat of battle” decision as well as those of his superiors and fellow battalion commanders raises some points of discussion.

Andrew volunteered for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1916 and later that year embarked for Egypt as a private in the Wellington Infantry Regiment. He first saw action and was wounded on the Somme, at Flers-Courcelette in September 1916. Made a corporal, he fought at Messines in June 1917. At Passchendaele in July 1917, Andrew, leading two infantry sections, destroyed a German-machine-gun nest. Eyeing another machine-gun position, Andrew, on his own initiative, attacked and captured it. Andrew and another man continued to scout forward, encountering a third machine-gun post, which they destroyed with hand grenades, and returned to report on enemy dispositions. For his leadership and bravery, Andrew was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) on July 31, 1917, at La Bassée, France, and promoted to sergeant. In early 1918, while in England for officer training, he was commissioned a second lieutenant. During the interwar period, Andrew held a number of posts and was made captain in 1937.

When World War II erupted, Andrew was sent to England in May 1940 as commander of the 22nd Battalion, 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd New Zealand Division. In March 1941, Andrew’s battalion first went to Egypt and then Greece, but after the debacle on the Peloponnese, his troops were evacuated to Crete in April 1941, becoming part of Commanding General Bernard Freyberg’s Creforce.

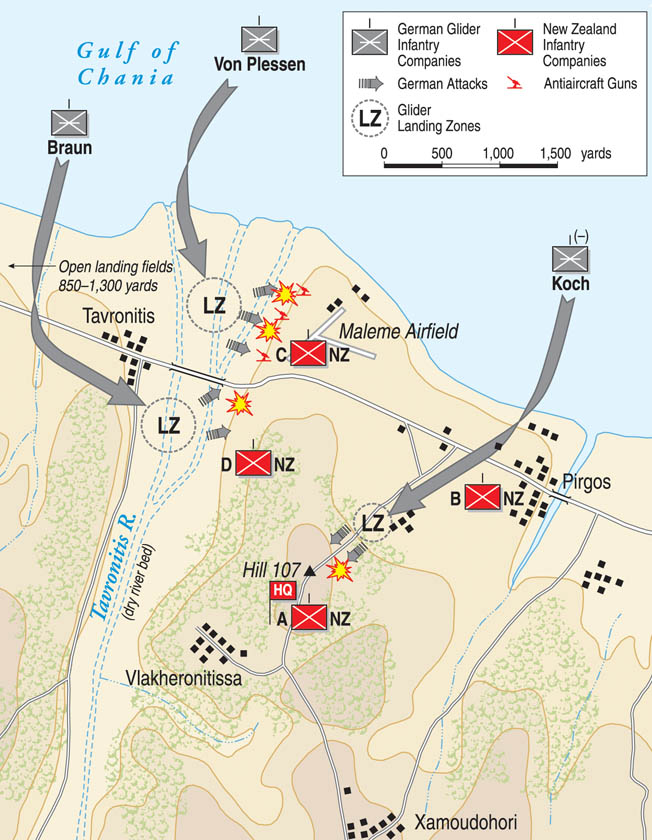

The 5th Infantry Brigade, composed of the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, and 28th (Maori) Infantry Battalions, was commanded by Brigadier James Hargest with his headquarters at Platanias, east of Maleme airfield. The 21st Battalion was holding an inland sector, Vineyard Ridge, while the 23rd Battalion’s area was north, extending toward the island’s only northern coastal road. Andrew’s 22nd Battalion was given the onerous task of defending a five-mile perimeter at the most western tip of the Allied line on Crete, which included the Maleme airfield, Hill 107 south of the airfield, the village of Pirgos on the northern coast road, and the eastern bank of the Tavronitis riverbed. Along with two other airfields further east on the northern coast of the island, Retimo and Heraklion, Maleme had to be held at all costs if Creforce was to be successful against the anticipated German airborne assault and possible seaborne landing scheduled for May 20.

Hill 107 was a prominent defensive position covering the entirety of Maleme airfield and the Royal Air Force (RAF) camp there. Andrew’s 22nd Battalion, with 20 officers and 600 other ranks at the battle’s start, consisted of battalion HQ atop Hill 107 and five rifle companies (A, B, C, D) and Headquarters Company, at Pirgos, which fought as a rifle company. The battalion reserve was Platoon A of Battalion HQ with two Matilda “I” tanks hidden north of the HQ ready for counterattack. Atop Hill 107, A Company occupied the high ground central to the battalion’s position. B Company held the ridge (to be subsequently referred to as RAP ridge) just to the southeast of Hill 107. C Company’s three platoons were disposed around the perimeter of the airfield extending to the Tavronitis road bridge. D Company held the east bank of the Tavronitis from and including the road bridge south to a point just southwest of Hill 107.

About a mile south, also on the east bank of the Tavronitis, was a platoon of the 21st Battalion. Two 3-inch mortars covered the airfield but lacked baseplates and were both short of ammunition. In the battalion perimeter but not under Andrew’s direct command were 10 (six mobile and four static) Bofors guns sited around the airfield, two 3-inch antiaircraft guns near Hill 107, and two 4-inch naval guns of the Royal Marines on Hill 107’s forward slopes above D Company’s right center. The heavier ordnance pieces were sited for coastal defense and were ineffective against low-flying troop carriers.

The 5th Brigade’s battle plan called for Colonel D.F. Leckie’s 23rd Battalion to hold its positions and support Andrew if called upon by flare signal. The 23rd Battalion’s casualties were light because its positions were under cover from aerial bombardments before and during the attack. Colonel J.M. Allen’s 21st Battalion, much understrength from losses in Greece, was instructed to choose one of three options when the attack began: to move to the Tavronitis, to replace 23rd Battalion if it moved to support Andrew, or to stand where it was.

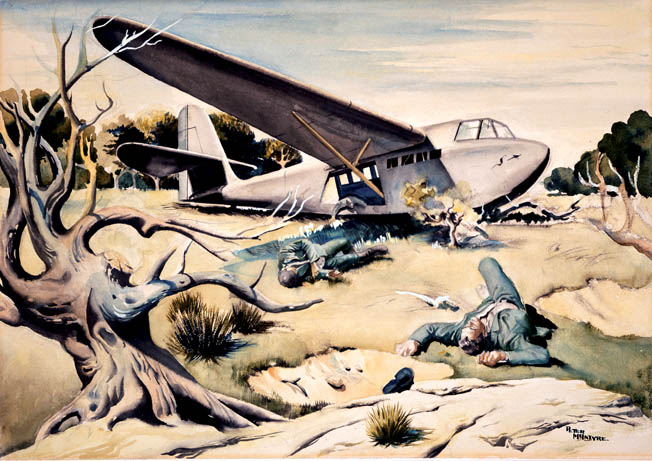

On May 20, beginning at 0800 hours, about 40 German gliders landed at the mouth of the Tavronitis and farther up the stony riverbed. These glidermen were to use the riverbed’s terrain to start their attacks on the airfield after crossing the road bridge. C Company, positioned around the airfield, engaged the Germans. D Company, overlooking the riverbed, wreaked havoc on the glider troops with accurate small-arms fire. Despite the casualties and steady New Zealander gunfire, Major Franz Braun of the Luftlandsturmregiment’s HQ was able to get his men across the riverbed on either side of the bridge. His superior, Brig. Gen. Eugen Meindl, observed that the line along the Tavronitis was not reinforced (containing only Andrew’s D Company), and he sent his II Battalion on a flanking movement to take Hill 107. Meindl knew the strategic importance of seizing the airfield and occupying Hill 107 to enable subsequent landing by air of German reinforcements to sustain the attack.

A critical sequence of events, which many believe represent the turning point of the entire 11-day battle, occurred during the afternoon and night of May 20, ultimately leading to the withdrawal of the 22nd New Zealand Battalion from Hill 107 during the early morning hours of May 21. Shortly into the attack, Andrew’s command post telephone lines to brigade HQ at Platanias and his companies were cut by bombs, rendering him unaware of the status of C and D Companies, which lacked wireless sets. Andrew had a wireless set that communicated solely to brigade HQ, and he informed Hargest’s staff at 1055 hours that contact with his forward C and D Companies had become disrupted. He could not make good visual contact with these forward companies through the bamboo thickets, olive groves, and a vineyard.

Andrew’s runners were ineffective because of marauding German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters. From the outset, Andrew could not operate his battalion as a unit. As noon approached, the German airborne troops near the Tavronitis bridge broke through between C and D Companies and overran the RAF camp. Andrew sent up flares, the prearranged signal, to call for the 23rd Battalion’s support, but they went unseen because of the dust and smoke.

At 1140 hours, the 23rd Battalion commander reported to brigade HQ, “Area well under control.” At 1345 hours, 21st Battalion reported to Hargest that its situation was satisfactory. Fifteen minutes later, Captain Dawson, a brigade staff officer, entered in his journal, “Meanwhile all things were confused but we did not feel that they were bad. We realized that 22 Bn was taking a hammering but we thought that the situation could be coped with.”

A seminal message was sent by Hargest at 1425 hours to 23rd Battalion, stating, “Glad your message of 1140 hrs. Will NOT call on you for counter-attack unless position very serious. So far everything is in hand and reports from other units satisfactory.” Hargest’s negation of 23rd Battalion’s counterattack was to have devastating consequences.

Events at the airfield and on Hill 107 were not going well despite Hargest’s optimistic mind-set. At 1455 hours, Andrew sent a wireless signal to Hargest that his battalion HQ atop Hill 107 had been penetrated by the Germans. Almost an hour later, Andrew reported to brigade HQ that his left flank had given way. Since he had no communication link to his remote companies, he requested that brigade HQ contact 22nd Battalion HQ Company at Pirgos to send desperately needed reinforcements.

In dire need of relief, Andrew contacted Hargest at 1700 hours and requested that 23rd Battalion launch its planned counterattack. Hargest denied the request, stating that 23rd Battalion was in the midst of combating its own German assault. In search of a solution to his predicament, Andrew launched a local counterattack on the gap between C and D Companies at the Tavronitis bridge with his Platoon A reserve and his two coveted “I” tanks. The attack failed, and he notified Hargest of this at 1745 via his wireless set and mentioned his contemplation of a limited withdrawal to RAP ridge where B Company was situated.

Hargest said, “If you must, you must.” He also promised to send two companies, one of the 23rd Battalion and one of the 28th (Maori) Battalion, to reinforce Andrew. At 1930 hours, the two reinforcing companies departed with the 23rd and the 28th Battalion companies scheduled to join Andrew at 2045 and 2100 hours, respectively. At 2100, Andrew told Hargest, via a weak signal on his wireless, that he was going to make his limited withdrawal of A Company and his battalion HQ to B Company’s RAP ridge on the eastern reverse slope of Hill 107. At this time only the 23rd Battalion’s reinforcing company had arrived.

Shortly thereafter, while waiting for the second reinforcing company’s arrival, Andrew decided that his new position on RAP ridge was untenable. He then made his momentous tactical error and withdrew the 250 surviving troops of A and B Companies under the cover of darkness. A Company of 23rd Battalion acted as a guide to cover the total withdrawal from Hill 107 to the line between 21st and 23rd Battalions on Vineyard Ridge. Andrew sent out runners to C, D, and HQ Companies, but none got through.

Almost oblivious to the events surrounding the abandonment of Hill 107, Hargest sent a message to Brigadier Edward Puttick, the division commander, relaying that 23rd Battalion and 7th Field Company were “tired but in good fettle … hundreds of dead Germans in the area … all units would be keeping a sharp watch on beach.” Some observers have cited Hargest’s poor judgment as a reason for not counterattacking immediately with 23rd Battalion, while others have wondered whether Hargest was just confused and misinformed.

Andrew’s decision, made during combat and amid the fog of war, ceded Maleme airfield to the Germans. By dawn on May 21, no New Zealand troops remained within the airfield perimeter. The survivors from D Company on the Tavronitis, upon learning that Andrew had left RAP ridge, had no alternative but to retreat. C Company’s commander learned of Andrew’s decision to withdraw from Hill 107 during the early morning hours of May 21, compelling him to lead his surviving troops away from the airfield at 0430 hours. Without Hill 107, direct fire from the New Zealanders could reach only the eastern end of the runway, making Maleme an effective operational enemy airfield before the second day of the battle commenced. The 100th Gebirgsjäger Regiment started to reinforce Maleme by 1700 hours on May 21.

The 22nd Battalion’s weaknesses at Maleme on May 20 were myriad. Given its casualties in Greece, it was insufficiently sized for a five-mile perimeter and its weapons were inferior in both number and quality. The battalion had only 60 percent of its machine guns, and the mortars lacked baseplates and sufficient ammunition. Eight of its 20 officers became casualties on May 20. Disrupted telephone lines from bomb damage and a wireless set shortage cannot be overemphasized as they contributed critically to Andrew’s ignorance of the fate and position of his C, D, and HQ Companies.

The two “I” tanks, which Andrew coveted for a local counterattack, proved useless against the German breach across the Tavronitis. One tank’s turret did not traverse, and its ammunition did not fit. The second tank’s turret jammed in the riverbed, and after its abandonment it served as a German pillbox. Artillery support was scanty, with Andrew’s requests denied as a multiplicity in command hampered tactical decision making. The antiaircraft guns, sited for coastal defense, could not combat the aerial assault at multiple locales. Finally, there was no response to the Luftwaffe’s incessant bombing and strafing of defensive positions and the New Zealanders’ troop movements, especially during the daylight hours.

As darkness descended on May 20, Andrew counted with certainty on only two (A and B) of his five companies. If D Company had been annihilated, as was suggested by a straggler, the enemy could cross the Tavronitis anywhere along its length. The prearranged counterattack he had expected from both the full 23rd and possibly the 21st Battalions never materialized, constituting a radical departure from the original battle plan.

Andrew was predisposed to use the cover of darkness to adjust his position on Hill 107 for better defense. This was preeminent in his mind-set when he spoke to Hargest about a limited withdrawal to his B Company HQ on RAP ridge after his local counterattack failed. After his first limited tactical withdrawal to RAP ridge, Andrew had become fearful of an attack from the southwest against his new front on RAP ridge, fretting that the remnants of his battalion might be driven off there by morning.

Finally, Andrew was unable to impress upon Hargest the magnitude of his predicament. Poor communications and dysfunctional discussions with Hargest failed to exhort Andrew to implement an alternative plan to defend Hill 107 other than total withdrawal. Exhaustion and a light wound compounded his pessimistic view of the tactical situation. Andrew may have been hasty, but the accumulation of faulty communication, heavy enemy attack, ceaseless aerial bombardment and strafing, failed counterattacks, and tardy reinforcement by Hargest’s two companies strongly influenced his plan for a second total withdrawal to Vineyard Ridge to join the line between 21st and 23rd Battalions.

Ironically, if Andrew could have observed his C and D Companies before nightfall, he would have seen that the former was still strongly defending the airfield and the latter was intact along the Tavronitis. C and D Companies had suffered many casualties, but they inflicted much greater losses on the invaders. Andrew was unaware of these facts and dwelled upon the strong German buildup to his west, which he believed would be hurled against his remaining A and B Companies.

The Allies might have held Crete had additional wireless radio sets been available among 22nd Battalion’s separated companies. As luck would have it, the other reinforcing company from the 28th Maori Battalion reached the airfield in the dark and was only 200 meters from C Company’s command post. However, the Maoris believed that C Company had been overrun and turned back, fearing a dawn air attack. Had the Maoris linked up with C Company and continued to defend the airfield on May 21, the course of the entire battle could have changed.

What else could Andrew have decided at B Company HQ on RAP ridge? Although the two reinforcing companies from 23rd and 28th Battalions might have been delayed, Andrew may have been too pessimistic once they arrived. As David Davin, the official New Zealand author for the campaign, wrote, “With their arrival, Andrew could have expected to have four reasonably strong companies with which to hold a narrower perimeter based on [Hill] 107…. So long as he held out, the enemy could not have secure possession of the airfield or give his undivided attention to driving further east.” Davin continued, “Andrew intended to put the two reinforcing companies on [Hill] 107 as they arrived and hold A and B companies on RAP ridge … this seems a much weaker plan than to concentrate his whole force on and around [Hill] 107 itself.”

Andrew had not entirely given up hope of holding Hill 107 since between 2100 and 2200 hours he positioned the newly arriving A Company from 23rd Battalion atop Hill 107 to enable his own A Company to withdraw to RAP ridge. In actuality, once Andrew made the first limited withdrawal of his A Company to RAP ridge versus holding the top of Hill 107 with all available troops, the drawbacks of this new position gnawed at him. Andrew reasoned that Hill 107 had previously been the center of his defensive system, and now it was held by only 23rd Battalion’s A Company. If that company failed to hold Hill 107’s crest the next day, the enemy would dominate RAP ridge, which was now 22nd Battalion’s main position.

RAP ridge had little natural cover, and Andrew’s men lacked tools and time to dig new defenses before dawn. Andrew feared his men’s exposure to the inevitable daylight aerial strafing and bombing in addition to small-arms fire from the German airborne troops. He anticipated heavy casualties among his surviving A and B Company troops, especially since they would be unable to extricate themselves during daytime.

Also, weighing unduly on Andrew’s mind was the absence of 28th Battalion’s reinforcing B Company and the continued silence of his own C, D, and HQ Companies, which seemed to confirm Andrew’s fears that they were annihilated. These pragmatic exigencies compelled Andrew to hastily decide on his second complete withdrawal from Hill 107 to the line between 21st and 23rd Battalions on Vineyard Ridge. If B Company of the 28th Battalion had arrived at the same time as A Company of the 23rd Battalion, it might have enabled Andrew to see that there were other options. Davin argued that with the two reinforcing companies arriving simultaneously, “there was still time to change his [Andrew’s] mind and go back to [Hill] 107. Failing such a reversal of plan, he had no course but to go on withdrawing; and how unfortunate for the future of the defence that course was.”

Who else made critical errors? Lt. Cols. Allen and Leckie should have implemented their preinvasion orders to counterattack immediately if the Germans secured a lodgement on the airfield. The 23rd Battalion and the understrength 21st Battalion were some distance away but should have been able to assist 22nd Battalion.

A lion’s share of the blame belongs to Hargest, who negated the preinvasion battle plan’s execution of sending in 23rd Battalion and perhaps 21st Battalion as well to assist 22nd Battalion if it were in dire straits. This one- or possibly two-battalion counterattack would have pushed the Germans back across the Tavronitis bridge and riverbed, as later attested by the Germans. Hargest’s sending of only two reinforcing companies was inadequate to assure a proper defense of Hill 107 and too tardy to counter Andrew’s heightening pessimism.

Paradoxically, it was Hargest, while failing to properly assess Andrew’s dire situation by remaining at his Platanias HQ, who possessed an unrealistically optimistic mind-set that he conveyed to both his subordinate battalion commanders and his superiors. Brigadier Puttick, too, failed to grasp Andrew’s serious predicament at Maleme airfield and Hill 107 on May 20 to properly ensure a more aggressive response on Hargest’s part. General Freyberg’s vacillation over an impending seaborne attack versus further air landings may have clouded his strategic thinking.

However, Hargest’s report of a “quite satisfactory” situation at Maleme only contributed to overall miscommunication along the chain of command, causing Freyberg to hesitate to commit the entire 23rd Battalion to counterattack and defend Maleme airfield early on May 20 because of its “responsibility for coastal defense.”

After its evacuation from Crete, 22nd Battalion regrouped in Egypt and entered the North African Campaign later in 1941, still under Andrew’s command. In late November 1941, the battalion, still part of 5th Infantry Brigade, was situated at Menastir, where the brigade HQ was overrun and Brigadier Hargest captured. Andrew took over as temporary brigade commander and “for outstanding skill and leadership over the very difficult period 25th November to 9th December” he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

Andrew relinquished command of his battalion on February 3, 1942, and returned to New Zealand, where he was promoted to colonel and took command of the Wellington Fortress Area. In 1952, Andrew was promoted to brigadier. He died on January 8, 1969, and his many medals, including the VC and DSO, are on display at the New Zealand Army Museum, Waiouru.

Jon Diamond is a frequent contributor to WWII History. His Command series book on Field Marshal Archibald Wavell was released by Osprey Publishing in 2012.

Appreciate if you have any info on whether 2nd NZ19 Army Corps was involved in the immediate defence of Maleme in the period you write of. Also were they involved in the 42nd Street fight? Many thanks