By William F. Floyd, Jr.

An armada of German Heinkel He-111 bombers droned through the Ukrainian night sky on September 21, 1944, en route to Poltava

Airfield in the Ukraine for a mission against American bombers parked at the base. The B-17 Flying Fortresses and their escort P-51 fighters were part of an experimental cooperative “shuttle” program between American and Russian forces known as Operation Frantic by which American strategic bomber crews based in England and Italy would fly against Axis targets in and around Berlin, lay over at Soviet Union airfields, and strike more targets on the return leg of their circuit.

The chief architect of the German bomber raid was General der Fleiger Rudolf Meister, the commander of Fliegerkorps IV, based at Brest-Litovsk. The mainstay of this particular air corps was the Heinkel He-111 medium bomber with a range of 1,400 miles. The bombers had been upgraded with advanced avionics and their crews were well trained in long-range navigation and target location. A group of Junkers Ju-88 pathfinder aircraft navigating electronically would guide the Heinkels to their target.

The armada took off from airfields near Minsk bound for their target 500 miles away. The Ju-88s dropped flares to mark the targets for the Heinkels. At 12:40 amthe Heinkels began dropping their ordnance. They roared over the airfield in several waves. Altogether, the bomb crews dropped 15 tons of high explosives on the airfield. The raid lasted 90 minutes during which the Soviets mounted a weak defense. No Soviet night fighters took off to contest the attack, and 50mm truck-mounted antiaircraft guns proved wholly inadequate for the task. Of the 73 B-17s parked at Poltava, 47 were destroyed and the remaining 26 suffered varying degrees of damage. In contrast, the Luftwaffe did not lose a single aircraft. It was an exhilarating triumph not only for Meister’s Fliegerkorps IV, but for the German military leadership and German people at a time when bad news from the front lines vastly outweighed good news.

After Germany’s defeat in World War I, the country was banned from having an air force by the Treaty of Versailles. In spite of this restriction, the Germans secretly began to rearm in the 1930s. One of the aircraft designers who most benefitted from the German rearmament was a short, bespectacled aircraft engineer named Ernst Heinkel. The native of Baden-Wurttemberg eventually became a Wehrwirtschaftsführer. Having paid his dues as an aircraft designer for various companies during World War I and in the early postwar period, 34-year-old Heinkel established his own company, Heinkel-Flugzeugwerke, in 1922 at Warnemunde in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania.

In the postwar period, Heinkel was fixated on fielding the world’s fastest passenger aircraft. He was passionate about high-speed flight and was keen on exploring different forms of aircraft propulsion. Because of his interest in propulsion, he donated aircraft to aviation wizard Wernher von Braun, who was exploring rocket propulsion for aircraft. Many of his colleagues in the German aircraft industry were dismissive of Heinkel’s concepts and ideas, but that was generally the case with all innovators.

In June 1933, Albert Kesselring, who at the time headed the Luftwaffe Administration Office, wanted to build a German Luftwaffe whose air wings were composed of modern aircraft. Kesselring convinced Heinkel to relocate his factory and increase his work force to 3,000 employees. Among the aircraft that Heinkel would develop under a government-sponsored program was a fast medium bomber. To disguise the work so that Germany would not be found in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, the Luftwaffe requested in 1934 that Heinkel design and build a commercial airliner incorporating Germany military specifications that could be converted to a medium bomber.

Heinkel entrusted the project to gifted aircraft designers Siegfried and Walter Gunter. The Gunter brothers designed what would come to be regarded as a classic World War II airplane. The He-111 not only incorporated the latest aerodynamic features and structural refinements, but also handled well and performed to the designers’ expectations.

The Gunter brothers had designed the He-70 Blitz, a German mail plane and fast passenger aircraft in 1932, and they incorporated many of its best features into the medium bomber they were building. The first prototype was tested in February 1935, but it was found to be under powered, and therefore required significant changes. The design team subsequently replaced the original 600 horsepower BMW engines with 1,000 horsepower Daimler-Benz engines for the 111B series.

The He-111E series aircraft came off the production line in February 1938 and were flown to Spain where they joined the bomber fleet operated by the German Condor Legion fighting for the Nationalist cause during the Spanish Civil War. Afterward, the Heinkel team made some minor refinements to the aircraft, such as raising the pilot’s seat so that he could see over the glazed cockpit if necessary because it proved difficult to see through in extremely bright sunshine and in rainstorms. During this period the crew increased from four to five as more machine guns were added for protection against enemy fighters.

The He-111P, which incorporated these improvements, went into action in the skies over Poland when the Germans invaded that country in September 1939. The Kampwaffe, or bomber force, in Poland consisted of 705 Heinkel He-111s and 533 Dornier Do-17s.

During the first half of 1940, the He-111s became a workhorse of the German Luftwaffe. They harassed British shipping in the North Sea, participated in the invasion of Denmark and Norway, and supported Wehrmacht forces in the Low Countries and France. They played a key role in the bombing of Rotterdam on May 14, 1940, which was intended to ensure the Dutch surrender. During the fall of France, they harassed Allied troops attempting to evacuate from the Dunkirk beaches.

After the fall of France, the Luftwaffe began preparing for the Battle of Britain. The He-111H, which could deliver 5,500 pounds of bombs, inflicted an impressive amount of destruction. Whereas in the Spanish Civil War the Heinkel bomber could outrun enemy fighters, this was not the case during the Battle of Britain. During the three-month campaign that began in July 1940, the Heinkels faced fierce resistance from Royal Air Force Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires. Their one advantage lay in their large numbers because there generally were not enough fighters in the skies to stop the incoming bombers. Still, the campaign revealed substantial defensive deficiencies in regard to speed, armor, and weapons.

In the strikes on Great Britain, it soon became evident that the bombers needed an escort. Even better, the bombers needed their own defensive capabilities. Heinkel engineers placed machine guns in the nose and tail and a 20mm cannon in the ventral gondola. To man the guns, it was necessary to add more crew as well. The aircraft eventually had five crewmembers: a pilot, navigator-bombardier-nose gunner, dorsal gunner/radio operator, ventral gunner, and side gunner. The redesign called for machine-gun positions in the glass nose and in the flexible ventral, dorsal, and lateral positions of the fuselage.

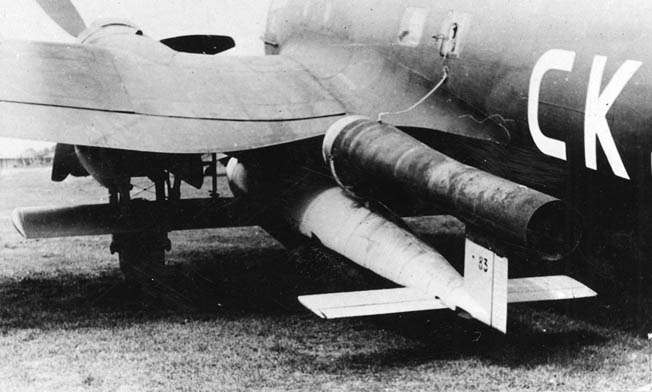

The Heinkel design team developed a variant specifically for attacking Allied surface vessels. The He-111J-1 was designed to serve as a torpedo bomber. It boasted two external torpedo racks in lieu of an internal bomb bay. But following a short period in service, the Kriegsmarine discarded it because the service felt it required too many crew members to operate.

The He-111 also saw action in the Balkans and North Africa and during the invasion of the Soviet Union. The He-111 would have a long career on the Eastern Front not only conducting raids against the Soviet rail network, but also serving as a transport workhorse along with the venerable Junker Ju 52. During the Battle of Stalingrad, the He-111F was one of the aircraft used to fly food and ammunition to the encircled German Sixth Army during the winter of 1942-1943.

The first versions of Germany’s V-1 Flying Bombs were launched in the summer of 1944 not from rocket launchers as they would be later in the war, but from He-111Hs. To launch the powerful weapon, the pilot approached the target below 300 feet to avoid detection by British radar. As the aircraft approached the coast of England, the pilot would increase the altitude of his aircraft to 1,700 feet, which was deemed the minimum altitude for a safe launching. He then released the cruise missile. Over a period of seven weeks, it was reported that the Luftwaffe launched more than 300 of the bombs against London. The initial missions achieved great success; however, during the next six months only 240 of the 1,200 V-1s reached their intended targets.

As the Luftwaffe was putting other bombers, such as the He-177 and the Dornier 217, into service, the He-111 became increasingly obsolete. As the war moved into its final phase, it became obvious that it was too late to begin developing a replacement for the He-111. For that reason, the Luftwaffe continued to produce the He-111, but eventually the beleaguered Third Reich stopped building bombers altogether in order to produce fighters to defend the Fatherland against Allied air raids. Altogether, Germany built 6,500 He-111s during World War II.

Unlike the prototype of the Heinkel He-111 that was passed off as a civilian passenger aircraft to disguise its real purpose as a medium bomber, the thin fuselage of the Dornier Do-17 V1 prototype built in 1934 could in no way fool anyone into believing it was a civilian airliner. The Dornier had seating for only a half dozen people behind the flight deck after which its fuselage tapered so dramatically that it earned the sobriquet “Flying Pencil.”

German aircraft builder Claude Dornier, whose firm Dornier-Werke was based in Friedrichshafen, intended the aircraft to be a fast mail plane. When the Luftwaffe high command got a look at it, they knew at once it could serve as a fast medium bomber. Following initial test flights in 1934, the Do-17E-1 bomber was ready for service in 1937 and could carry a 2,200 poujnds of bombs. Although this was less than half of what the Heinkel He-111 could deliver against a target, the Dorniers achieved far greater accuracy than the Heinkels.

For protection against fighters, the Do-17 had a 20mm cannon and three hand-aimed MG 15 machine guns. The Do-17E’s performance with the Condor Legion in the Spanish Civil War revealed that it was highly vulnerable to Soviet-made Polikarpov I-16 fighters used by Republican forces. To remedy this, the Dornier Do-17Z series, which became the most heavily produced variant, featured an expanded cockpit and canopy to accommodate a rear gunner position. In addition, the designers improved the arcs of fire for its machine-gun positions and installed side machine guns in the cockpit.

The Luftwaffe halted production of the Do-17 in mid-1940, though, in favor of the more powerful Do-217. Production on the Do-217 began in late 1940. It entered service in early 1941 and by the beginning of 1942 was being produced in significant numbers. The Do-217 fulfilled a number of roles during World War II. These included use as a conventional bomber, floatplane, reconnaissance aircraft, and night fighter.

Manned by a crew of four, the Do-217E-1 had a single 15mm MG151 cannon mounted in the nose along with five 7.9mm machine guns that provided defensive armament. These were not as effective as one might think, because the radio operator was assigned to operate multiple machine guns. The Do-217E-1 was followed by the 217E-2, the first version to feature a gun turret in the aft cockpit.

The Dornier team further improved its defensive capability against fighter aircraft by installing a twin, and later quadruple, MG 81 machine gun position in the tail cone. The boasted an impressive bomb load of 8,800 pounds of which 5,550 was inside the bomb bay and the rest mounted externally.

The Do-217E-3, which had been developed for antishipping operations in the Atlantic, carried additional armor plating and two additional fuel tanks in the bomb bay. It was armed with seven MG 15s supplementing a single 20mm MG FF cannon in the nose. The 217E became operational in a reconnaissance role in the closing months of 1940 and as a bomber in the spring of 1941.

In the fall of 1942, Dornier introduced the 217K-1 bomber which had a new glazed nose with an unstepped cockpit. The 217K-2 was the model that sank the Italian battleship Romaon September 14, 1943, when the Italian fleet broke out from La Spezia to join the Allies.

The lack of a long-range heavy bomber in the Luftwaffe’s inventory of aircraft can be traced back to the decision in prewar planning that the Luftwaffe was to serve as an appendage to the German Wehrmacht. The Luftwaffe high command was full of ex-Wehrmacht officers who believed wholeheartedly that the air force should function in a strictly support role. A strategic air force would only be contemplated if it became absolutely necessary.

The Luftwaffe was to achieve and maintain air superiority over enemy air forces and, at the same time, it was to support the Wehrmacht and Kriegsmarine. In this approach, German dive bombers, such as the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka, and the medium horizontal bombers, were to serve as aerial artillery. Luftwaffe aircraft were to disrupt enemy communications, destroy railroad infrastructure, and shatter enemy troop concentrations.

In some respects Germany was so severely handicapped by the Treaty of Versailles that there was little chance it could get enough of a head start in bomber development to field a heavy bomber for such important aerial campaigns as the Battle of Britain. In 1933 the airplane industry in Germany was practically non-existent. This was aggravated by the lack of raw materials and the long lead time between design and production. Generally, it took the Germans at least four years to get a new aircraft from design to production.

Yet when it came to defeating Great Britain, the shortsightedness of the approach became all too apparent. The blame lies squarely with German leader Adolf Hitler. When asked to throw his support behind the establishment of a heavy bomber program, Luftwaffe Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring explained that Hitler cared little for the idea. Hitler was more interested in quantity over quality, according to Göring. Luftwaffe Chief of Staff General Walter Wever had been the strongest advocate for a long-range heavy bomber, but he died in an airplane crash in 1936.

Before his untimely death, Wever had started a four-engine long-range strategic bomber program under the name Uralbomber. Technical problems, such as underpowered engines and excessive fuel consumption, led to his successor General Albert Kesselring’s decision to cancel the Junkers Ju-89 and Dornier Do-19 four-engine bomber programs on April 29, 1937. From a production standpoint, it might have been the right decision because for every four-engine heavy bomber that Germany manufactured, it could produce two and a half twin-engined medium bombers.

Begun in the same time frame, Heinkel’s Project 1041 program moved slowly forward. The Gunter brothers designed a bomber that included many radical design concepts and features. The He-177 Griffen was an impressive achievement. Although the aerodynamically clean tube-like fuselage was a marvel to behold, the rest of the aircraft was so poorly conceived as to manifest one glitch after another. These were not minor glitches by any means, but major glitches involving various aspects and components of the engines.

The first V1 prototype flew in 1939. It handled well, but its speed and range were insufficient. More than a half dozen other prototypes followed, one of which had triple bomb bays, but serious engine fires plagued many of those tested. The sticking point ultimately became the need to resolve the problems associated with the aircraft’s power plants. The attempt to have the He-177 in production by 1940 was unrealistic.

In October 1942, Heinkel began delivering the heavy bombers for service; however, the manufacturing facility in Oranienburg in the Brandenburg region could only turn out five per month, whereas it was supposed to be putting out 70 per month. By then Hitler had taken a keen interest seeing it as a way to bomb deep behind the lines on the Eastern Front, as well as escort German U-boats and blockade runners in the Atlantic Ocean. Heinkel ultimately produced 170 177A-3s in 1943 and 261 177A-5s in 1944.

The He-177 participated in Operation Steinbock in early 1944. The program was conceived as a way to get revenge against the Allies for their strategic bomber attacks on Germany. But the results achieved were hardly worth the effort. For example, on February 13, 1944, 13 took off. Of those, eight returned with overheated or burning engines, four reached the target, and one went missing.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments