By Joshua Donohue

“All hands have behaved splendidly and held up in a manner in which the Marine Corps may well tell.”

—Major Paul A. Putnam, Commander VMF-211

On November 28, 1941, U.S. Marine Corps Major Paul A. Putnam sailed for Wake Island aboard the USS Enterprise (CV-6). Putnam and 11 other Leatherneck aviators of Marine Fighting Squadron 211 (VMF-211) prepared to fly their Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats to reinforce the small U.S. Pacific outpost located some 2,000 miles west of their base at Ewa Mooring Mast (Territory of Hawaii).

Four days after the 38-year-old major and VMF-211 arrived on Wake, the atoll was attacked by Japanese bombers within hours of the raid on the U.S. Pacific fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor.

Paul Albert Putnam was born in Milan, Michigan, on June 16, 1903, but grew up in the town of Washington, Iowa, where his father moved the family business in 1909. After graduating from high school, Putnam attended Iowa State University at Ames, majoring in civil engineering. During his sophomore year, Putnam decided to leave collegiate life behind; he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on December 1, 1923.

Over the next several years, Putnam served in a variety of interwar assignments, including occupation duty in Nicaragua as the United States attempted to help the elected government overcome a leftist insurgency.

Deciding to make the Marines a career, Putnam applied for officer training and was accepted; he was commissioned a second lieutenant on March 3, 1926. In early 1927, he returned to Nicaragua as an officer with the 23rd Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, 2nd Marine Brigade and in January 1928 got his first taste of combat against rebel forces.

In June 1928, he returned to the United States and applied for aviation training, earning his wings on May 7, 1929. It was back to Nicaragua, where he conducted a series of bombing and strafing runs against the rebels. He remained on duty in that Central American country until July 1938. Two years later he was promoted to major and, in January 1941, sailed for Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with Marine Fighting Squadron 2 (VMF-2). On July 1, 1941, VMF-2 was redesignated VMF-211 while attached to the 2nd Marine Aircraft Group (later MAG-21).

By October 1941, VMF-211 was transitioning from its obsolete F3F-2 biplane, nicknamed the “Flying Barrel” because of its bulbous shape, to the sleek, new Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters. Unfortunately for Putnam and his Leatherneck aviators, they did not have adequate time to familiarize themselves with their new planes by the time they departed for Wake Island the following month.

Major Putnam became commanding officer of VMF-211 on November 17, 1941, as plans were already being set in motion to send his squadron to the Wake atoll. On November 27, Putnam received secret orders from his commanding officer, Lt. Col. Claude A. Larkin of MAG-21, to deliver 12 of VMF-211’s Wildcats to Wake Island aboard the USS Enterprise.

As relations between the United States and the Japanese Empire continued to deteriorate during the fall of 1941, reinforcing the American Pacific outpost at Wake took on a greater sense of urgency.

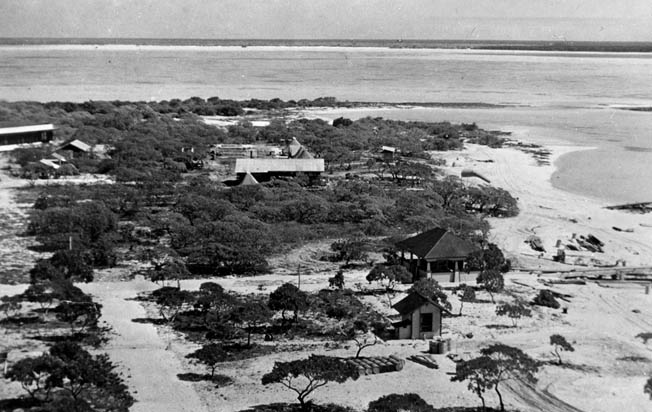

Wake Island is a V-shaped atoll consisting of three separate islands: Wake proper, Wilkes located on the southern tip, and Peale on the northern tip. Prior to the arrival of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion in August 1941, Wake had been a regular stop for Pan American Airways (PAA) and its Martin M-130 Clipper flying boats.

PAA also built a hotel complex on Peale Island, making Wake a favorite destination for tourists. In addition to the PAA personnel, 1,200 civilian workers employed by the Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases (CPNAB) were responsible for the construction of Wake’s buildings, base facilities, and road networks.

Major Putnam and 11 other Marine aviators (10 officers and two enlisted) of VMF-211 took off from Ewa on the morning of November 28, making the short flight to Naval Air Station Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor to await further orders. His men were under the assumption that this was a routine overnight training mission to Maui and packed nothing more than an extra set of clothing, razors, and toothbrushes.

Putnam returned with instructions for his aviators to depart Ford Island and rendezvous with the Enterprise and Task Force 2 already at sea. Once they formed up over Vice Admiral William F. Halsey’s flagship, Putnam and his fliers were signaled to land aboard the carrier, a clear indication to the rest of VMF-211 that this mission was more than routine.

As soon as Putnam and his men landed on the Enterprise, Halsey’s official Battle Order Number One was relayed to the Marine aviators. The message indicated that the Enterprisewas operating under wartime conditions and that VMF-211’s new destination was Wake Island.

While Putnam was already aware of his mission, his request to Halsey for further instructions did not assuage any lingering uncertainty. “Putnam,” explained Halsey, “your instructions are to do what seems appropriate when you get to Wake.”

The men of Enterprise quickly went to work on VMF-211’s dozen F4F-3s under Putnam’s watchful gaze as the carrier began a westerly course toward Wake. Halsey was also quick to replace one of VMF-211s Wildcats that was left on Ford Island with starter trouble.

In a letter to Lt. Col. Larkin on December 3, Putnam brilliantly (and sarcastically) summarized the situation he faced: “Immediately I was given a full complement of mech[anic]s and all hands aboard have vied with each other to see who could do the most for me. I feel a bit like the fatted calf being groomed for whatever it is that happens to fatted calves, but it surely is nice while it lasts and the airplanes are pretty sleek and fat too.”

Just before 7 am on December 4, 1941, Major Putnam and VMF-211 took off from the Enterprise as she stood 200 miles from Wake. The 12 Wildcats were escorted to the atoll a few hours later by a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat sent from Wake.

The Marine aviators touched down on the atoll’s 5,000-foot, coral-packed runway and were greeted by the ground elements of VMF-211 who had been sent to Wake aboard the ancillary ship USS Wright less than a week before.

Putnam immediately reported to Commander Winfield Scott Cunningham, who had assumed overall command of Wake from USMC Major James P.S. Devereux. Upon his return to the airfield, Putnam had his first opportunity to assess the condition of his squadron’s parking area. He quickly determined that there was much work to be done.

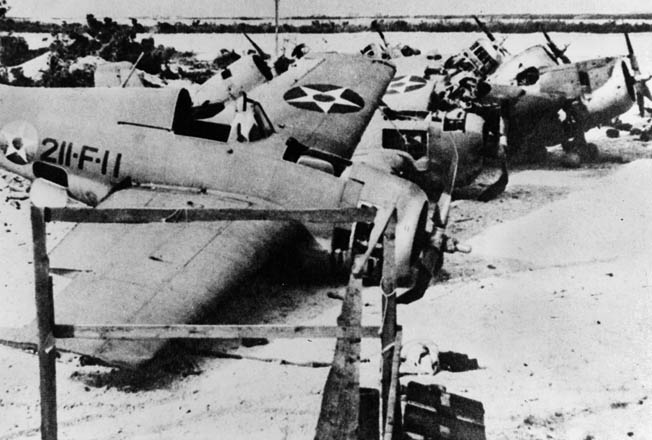

Putnam’s immediate concern was the lack of protective revetments for his fragile Wildcats, which sat out in an open parking area located along the southern edge of Wake’s main runway. The terrain was both rough and uneven with loose pieces of coral surrounding most of the area where VMF-211 was forced to park its planes.

Due to the uneven areas and loose coral that surrounded the hardstand mat, Putnam attempted to keep the fragile Grummans as widely dispersed as he could to avoid certain damage. One author stated, “The only safe spot for parking F4F-3s was a hardstand mat no more than 300 by 800 feet in size.”

The cross runway was still under construction while the main runway was too narrow to allow multiple aircraft to take off at the same time.

Sitting adjacent to the parking mat were two elevated 25,000-gallon fuel tanks and more than 600 55-gallon fuel drums. Fueling had to be done by hand pumps, and the ground crews who were tasked with maintaining the F4F-3s were unfamiliar with the newly acquired airframes.

Putnam also needed additional manpower from the civilian workers of the CPNAB to aid in the construction of bunkers, foxholes, and aircraft revetments. The major’s frustration with the slow progress of these projects was evident in his initial operations report from Wake: “Backed by a written request from the Commander, Aircraft Battle Force, a request was made through the Island Commander to the Civilian Contractor’s superintendent on the morning of 5 December, asking for the immediate construction of bunkers for the protection of aircraft, and outlining various other works to follow. Great emphasis was put on the fact that speed, rather than neatly finished work, was required.

“However, an inspection that afternoon revealed a young civil engineer laboriously setting out stakes with a transit and three rodmen. It required an hour of frantic rushing about and some very strong language to replace the young engineer and his rodmen with a couple of Swedes and bulldozers.”

Ever since the F4F-3s were assigned to them back in Hawaii, the Marine airmen of VMF-211 attempted to gain as many flight hours in their new Grummans as they possibly could. None of the pilots had fired the Wildcat’s four .50-caliber machine guns, nor had they dropped bombs from them.

The planes also did not have armor, and only two of them had self-sealing fuel tanks. The F4F-3s carried a 100-pound bomb under each wing, but the planes lacked the correct suspension racks needed to carry the ordnance available at Wake. Captain Herbert C. Freuler quickly devised a modified mechanism made from the bands taken from practice bombs that worked flawlessly.

Commander Cunningham ordered Major Putnam to fly combat air patrols consisting of four aircraft aloft during dawn, midday, and evening hours. The patrols were of vital importance since the Wake garrison did not have a radar system and the noise produced from the pounding surf made it difficult to detect the sound of incoming aircraft.

The first patrol on December 5 was meant for VMF-211’s aviators to gain further experience in the Wildcats while also attempting to establish air-to-ground communications. One of Putnam’s pilots, 2nd Lt. John F. Kinney, fashioned a homing beacon for the Grummans that allowed them to pick up signals from VMF-211’s ground radio.

Major Devereux gave the Marines of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion and VMF-211 the day off on Sunday, December 7 (Wake time). The morning of December 8 began with the dawn patrol, and the first chance for the Marine pilots to fire the Wildcats’ .50-caliber machine guns was scheduled for later that day.

The protective works were set for completion by the early afternoon as Putnam’s frustration with the CPNAB laborers continued to grow.

Just before 7 amon December 8 (December 7 in Hawaii), Wake’s U.S. Army radio truck picked up a frantic message coming from Hickam Field, just across from Pearl Harbor: “Air raid Pearl Harbor. This is no drill.” The surprise Japanese attack on military installations across the island of Oahu was on and had thrust the United States into war with Japan.

Major Devereux ordered general quarters for his Marines to man their positions across the atoll, while Major Putnam was already in the air with a four-plane patrol by the time the news was delivered to the squadron. He immediately put VMF-211 on a wartime status when he was informed of hostilities with Japan and went back aloft leading the followup patrol. Upon landing, his executive officer and squadron favorite, Captain Henry Talmage Elrod, relieved Putnam for the midday patrol.

The Japanese Air Attack Force Number 1 of the 24th Air Flotilla (Chitose Air Group) was based on Roi Atoll in the Marshall Islands, located just over 700 miles south of Wake. At dawn, a flight of 27 Mitsubishi G3M2 Type 96 bombers (Allied code name “Nell”) departed Roi for Wake with their deadly payloads of fragmentation bombs and incendiary bullets. Not only were the Marines unfamiliar with the G3M2 Nells in terms of their appearance, but they also underestimated the abilities of the aviators who flew them.

Commander Cunningham recalled the Philippine Clipper that had taken off from Wake’s lagoon on a course for Guam before word of the attack on Pearl Harbor was received. When the Martin M-130 landed, Putnam scheduled a meeting with the Clipper’s captain, John Hamilton, who would go aloft with two of VMF-211’s Wildcats for a long-range reconnaissance patrol around the atoll to search for any Japanese threats from the air or sea.

Eight of Putnam’s Wildcats were sitting on the ground as widely dispersed as possible, while the other four were aloft at 12,000 feet above Wake. As noon was approaching, VMF-211 and the Marines of the 1st Defense Battalion were still hard at work reinforcing their respective positions. Putnam and his squadron were gathered in the path of an oncoming rain squall that was about to descend on Wake’s airfield.

At 11:58 am, the officers and enlisted men of VMF-211 were busy with their new assignments as the formation of Nells headed toward the southern edge of Wake proper with the airfield in their sights. Using low-hanging clouds to mask their approach, the 27 G3M2s broke through the clouds at 1,500 feet as Wake’s lookouts got their first glimpses of the approaching bombers.

By the time Putnam and his men heard the sound of aircraft engines, they only had seconds to take cover as Japanese bombs and machine-gun bullets rained down on the airfield’s crowded parking area. At the moment of attack, Putnam’s ground crews were busy loading the Wildcats with fuel, bombs, and .50-caliber bullets.

Putnam’s engineering officer, 1st Lt. George A. Graves, and 2nd Lt. Robert A. Conderman were in the flight tent going over the final details of the reconnaissance flight with the Philippine Clipper when the air raid alarm sounded. As Graves made a dash for his Wildcat, he was killed instantly by a direct bomb hit as he was climbing into his cockpit. Conderman also reached his Wildcat only to be struck in the legs and neck by bullets as his plane exploded, pinning his body beneath the burning Grumman. A third pilot, 2nd Lt. Frank J. Holden, was cut down by bullets while attempting to find cover. Second Lt. Henry G. Webb sustained serious wounds, while Captain Frank C. Tharin and Staff Sgt. Robert O. Arthur received minor wounds during the raid. Major Putnam sustained a painful wound from a bullet across his left shoulder while the horrific scene played out before his eyes.

The Chitose Air Group also attacked the Marine barracks at Camp 1 just beyond the end of Wake’s runway. The Nells then turned their sights on Peale Island and Camp 2 on Wake’s northern end where the civilian contractors were quartered. Bombs landed on the Pan American Hotel complex on Peale, killing nearly a dozen civilian employees. The Philippine Clipper was also subjected to strafing but was not seriously damaged.

After the Nells finished their attack runs and began their flight back to Roi, USMC Major Walter L.J. Bayler and Commander Cunningham were among the first to find Major Putnam bleeding from his wound and staggering near the runway in an almost “trance-like” state from the harrowing, near-death experience.

Putnam quickly regained his composure and began to reorganize his squadron while aiding in the evacuation of VMF-211’s dead and wounded. Major Bayler remarked, “As for Putnam himself, I’ve never seen a man change so completely.” Bayler further added that Putnam “emerged from the first smoke of battle as the iron-jawed commander of a hard-fighting outfit, forceful, energetic and resourceful.”

VMF-211 sustained over 60 percent casualties (23 killed, 11 wounded) following the Chitose Air Group’s opening strike on Wake. Three of Putnam’s pilots were killed, including Lieutenant Conderman, who died at the hospital later that same evening. VMF-211 also lost irreplaceable ground personnel and equipment following Japan’s daring raid.

Seven of VMF-211’s Wildcats in the parking area were completely destroyed, while an eighth was heavily damaged by bullets and shrapnel. Both of the 25,000-gallon aviation fuel tanks beside the parking mat were completely destroyed along with several 55-gallon drums sitting nearby. Putnam’s squadron lost spare aircraft parts, tools, radio equipment, oxygen supplies, and numerous documents and reports pertaining to the squadron’s operations. To make matters worse, Captain Elrod’s Wildcat was damaged when its propeller struck bomb debris near the parking area as he taxied back from his patrol.

Major Putnam immediately assigned 2nd Lt. Kinney as his engineering officer following the death of 1st Lt. Graves. “Kinney,” Putnam told him, “you are now the squadron’s engineering officer. We have four planes left. If you can keep them flying, I’ll see that you get a medal as big as a pie.”

Kinney, along with Tech. Sgt. William J. Hamilton, worked tirelessly to keep the remaining Wildcats in flyable condition. They were later assisted by Aviation Machinist Mate First Class James F. Hesson. The men spent much of their time scavenging the wrecks of destroyed Wildcats to keep the remaining planes airworthy throughout the course of the siege.

By the evening of December 8, the aviation Marines and the CPNAB contractors had completed the construction of several bunkers, foxholes, and lightproof aircraft revetments that allowed maintenance on the Wildcats to continue during hours of darkness.

The next morning, a formation of 27 Nells of the Chitose Air Group arrived over Wake at approximately 11:45. The twin-engined bombers approached at 13,000 feet, concentrating their attacks on the civilian hospital and barracks at Camp 2, along with the Naval Air Station on Peale. Fifty-five CPNAB workers were killed, while Marine casualties were light.

Major Devereux’s 3-inch gunners brought down one of the attackers and sent a number of others home damaged by shrapnel. Two of Putnam’s pilots rose to meet the Nells and scored the first victory for the squadron when 2nd Lt. David D. Kliewer and Tech. Sgt. William Hamilton downed one of the Nells. Putnam later wrote in his December 9 action report, “They never, after that first day, got through unopposed.”

At 10:45 on the 10th, the Japanese arrived over Wake with a flight of 26 or 27 G3M2s for a third straight air raid. Putnam’s executive officer, Captain Henry Elrod, was already aloft and was able to intercept the formation with his .50-caliber machine guns blazing away at the bombers. Elrod shot down two Nells, earning him the nickname “Hammering Hank.”

Casualties were light, and VMF-211 had inflicted losses on the Chitose Air Group for the second consecutive day. Putnam’s squadron had stood its ground after suffering terrible losses on December 8 and word of VMF-211’s exploits quickly spread across the atoll. The news not only lifted the morale of Wake’s garrison, but also in the United States shortly after.

In the early morning hours of December 11, Major Devereux’s lookouts spotted lights out to sea. The Japanese were sending an amphibious invasion force consisting of three light cruisers (Yubari, Tenryu, Tatsuta), six destroyers (Hayate, Oite, Mutsuki, Kisaragi, Mochizuki, Yayoi), two transports, (Konryu Maru and Kongo Maru), and two destroyer transports (Patrol Boats 32 and 33). Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka of Destroyer Squadron 6 was in overall command of the Wake invasion force when it sailed from Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands.

Devereux alerted his gunners and ordered them to hold their fire until he gave word. When the cruiser Yubari (Kajioka’s flagship) closed within 4,500 yards of Wake, Devereux ordered his 5-inch gun crews to open fire. The 1st Marine Defense Battalion scored multiple hits on Kajioka’s ships, including the destroyer Hayate, which was sunk by a direct hit from a 5-inch shell from Battery L on Wilkes Island, claiming the lives of all 167 sailors on board.

Putnam, Elrod, Freuler, and Tharin were already in the air when they confirmed to Major Devereux that no Japanese aircraft carriers were in the vicinity. Putnam and his aviators located Kajioka’s ships and began to bomb and strafe the vessels now in full withdrawal from Wake.

The four Wildcats made their bombing runs into a barrage of heavy antiaircraft fire from the cruisers, destroyers, and transports while raking their decks with .50-caliber machine-gun fire. Putnam, Tharin, and Freuler attacked the light cruisers while Elrod dove down on the destroyer Kisaragi. He scored a bomb hit on the retreating destroyer, but his Wildcat sustained damage from the ship’s gunners, forcing him to crash-land on Wake.

As Putnam and 2nd Lt. Kinney later approached the sinking Kisaragi, damage from Elrod’s bomb caused the ship to explode, claiming the lives of all sailors on board.

Only two Wildcats remained, but Putnam quickly sent them up for the midday patrol with Lieutenants Kinney and Carl Davidson at the controls. The pilots did not have to wait long until 17 G3M2s arrived over Wake. Davidson downed two of the Nells, while Kinney accounted for one probable.

Although VMF-211 had suffered, so had the Japanese. With two to three bombers shot down and Captain Elrod’s sinking of the Kisaragi, December 11 had been a historic day for Major Putnam and his men. But the odds were not in their favor.

Early the next day, a pair of Kawanishi H6K4 “Mavis” flying boats of the Yokohama Air Group based in Majuro attacked the atoll in Wake’s fifth air raid. Captain Tharin, who was already aloft on the dawn patrol, intercepted one of the raiders and quickly shot it down. Another victory for VMF-211 was scored on the evening of the 12th by Lieutenant Kliewer when he sighted and sank a Japanese submarine lurking in the waters off the atoll.

Putnam and the rest of VMF-211 were able to resume their duties for the remainder of the 12th and 13th as there was no sign of the Chitose Air Group on either day. The lull also gave Putnam an opportunity to relocate his command post to a more concealed position on the eastern side of VMF-211’s charred parking area.

By December 13, many of the civilian workers of the CPNAB were understandably apprehensive about working anywhere near the airfield. As more of the laborers failed to return to their assigned work stations around the airfield, Putnam’s frustration with the CPNAB workers and their superintendent, Dan Teeters, had reached a boiling point.

Following his disagreement with a group of CPNAB workers at the airfield after his arrival on December 4, he conferred with Commander Cunningham and requested more assistance from them. Putnam noted in his official report that the pace of construction work for his squadron was “progressing with slowness and confusion” and that Cunningham denied his repeated requests to round up civilian workers and force them to remain with VMF-211.

December 14 began with another early morning raid by the Yokohama Air Group when a group of Kawanishi flying boats bombed the atoll without causing damage. At noon, while Kinney, Hamilton, and Aviation Machinist Mate First Class James Hesson were working to get a third Wildcat back to operational status, 30 Nells arrived over Wake. A bomb scored a direct hit on a Wildcat inside a revetment, but Kinney and his assistants were able to salvage the engine from the burning plane by using a makeshift hoist. Putnam noted that the herculean efforts of the three men were “the most outstanding event of the whole campaign.”

Back at Pearl Harbor, a rescue mission was being planned to reinforce Wake’s garrison and evacuate the civilian personnel. Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, still reeling from the shock of Japan’s attack on his naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, organized an operation to reinforce Wake with additional ammunition, supplies, aircraft, and radar, as well as a contingent of Marines from the 4th Defense Battalion.

Kimmel dispatched Task Force 14, under the command of Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, consisting of the seaplane tender USS Tangier (carrying all supplies and men of the 4th Defense Battalion) and aircraft from the carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) to deliver fighters from VMF-221.

The task force departed Pearl Harbor on December 15, covered by Task Force 11, which served as a diversionary tactic to distract any Japanese attention from Saratoga and Tangier. When Admiral Kimmel was relieved of his command on December 17, his temporary replacement, Vice Admiral William S. Pye, would determine the fate of Wake’s ambitious rescue attempt in the coming days.

Putnam conducted the morning patrol on the 15th with the only operational Wildcat, but to his chagrin the Chitose Air Group never arrived. A flight of Mavis flying boats attacked Wake that evening, but their raid caused only minor damage. Thirty-two Nells bombed Wake the following afternoon, with the 1st Defense Battalion gunners claiming one shot down while damaging an additional four or five to the point that they could not make the return trip home.

The Japanese struck again on the 17th when 27 Nells attacked the atoll from 18,000 feet, followed by another raid in the late afternoon by the Yokohama Air Group. The Chitose Air Group did not attack Wake on the 18th but resumed its bombing campaign on the 19th when another 27 Nells bombed Peale Island and Camp 1 without causing significant damage.

On the afternoon of December 20, a lone U.S. Navy PBY landed in Wake’s lagoon with long-awaited news of the relief force that was en route from Pearl Harbor. The Catalina was set to depart Wake for Midway the following day with Major Bayler, who had been ordered to set up radio communications there, as the only passenger.

Putnam handed Bayler his operations report, which was to be delivered to Lt. Col. Larkin upon Bayler’s return to Hawaii. Putnam also scribbled a two-page letter to his wife Virginia back home in California. “War sure is hell,” Putnam wrote. “Not much squadron left, but what there is, is still in there swinging at ‘em.”

The PBY carrying Bayler lifted off from Wake’s lagoon at 7 amon the 21st. Bayler would famously become known as “the last man off Wake Island,” as the twin-engined patrol plane winged on an easterly course toward Midway Atoll. The Japanese attacked Wake just over two hours later, only this time with planes from aircraft carriers.

The Japanese detached the aircraft carriers Hiryu and Soryu (Carrier Division 2) from the returning Pearl Harbor Task Force and launched a wave of planes, including 18 Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighters, to strike Wake.

Putnam was in the vicinity of Camp 2 when he heard the roar of the incoming planes. He jumped into the nearest truck and made his way toward the airfield. As the major sped down the main access road from Camp 2 to the airfield, he was repeatedly forced from the road by strafing aircraft. Barely escaping the ordeal, Putnam jumped into Wildcat number 9 and took off in pursuit of the attackers in the hope that he could locate the carriers.

After losing sight of the Japanese planes, Putnam returned to Wake in frustration. Although he was unsuccessful in his attempt, he would later earn the Navy Cross for this action.

Twenty-seven Nells from Roi bombed Wake a few hours after the naval planes of the Hiryu and Soryu struck the first blow of the day. With the arrival of the Japanese carrier planes on the 21st, the consensus among many of the Wake Islanders was that another landing attempt was forthcoming.

On the morning of December 22, Captain Freuler and 2nd Lt. Carl Davidson were on patrol when they spotted a large group of carrier planes headed toward the atoll. Freuler shot down two Nakajima B5N Type 97 “Kate” bombers, but his Wildcat was damaged by debris after one of the B5Ns exploded below him. Freuler then sustained wounds from an attacking Zero and was forced to land back at Wake. Davidson was last seen with a Zero on his tail and never returned to the atoll.

With his final two Grummans out of commission, Putnam gathered the remaining personnel of VMF-211 and reported to Major Devereux as infantry. When Japanese ships were reported out to sea around 1 am on December 23, Devereux ordered Putnam and his group of around 30 Marines and civilians to protect the 3-inch antiaircraft gun manned by 2nd Lt. Robert M. Hanna, located south of the airstrip; Putnam was armed only with his .45-caliber pistol.

Putnam and his men arrived at the gun position not a moment too soon, for the Japanese had ordered two converted destroyer transports, Patrol Boats 32 and 33, to ground themselves on the reef along Wake’s southern shoreline and send their men into the attack. Despite heavy fire from Hanna’s “anti-boat” gun that ripped into the craft nearest to his position, Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) troops frantically roped down or jumped off both transports to assault the defenders.

Major Putnam, along with Captains Elrod and Tharin, formed a defensive line around Hanna’s gun, but the Japanese were pouring men onto both Wake and Wilkes Islands where a chaotic, close-quarter battle was rapidly unfolding under the night sky.

Elrod blazed away at the invaders with his Thompson submachine gun but was later killed by an SNLF rifleman as he attempted to throw a grenade. The death of “Hammering Hank,” a favorite among his fellow Marines and the CPNAB workers, came as a tremendous loss for the remaining defenders. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the siege.

Major Putnam was also wounded in the face and neck by a Japanese bullet but continued to fight on despite drifting in and out of consciousness from blood loss.

The Wake relief force was at sea approximately 500 miles to the east but was delayed by bad weather. Admiral Pye was less than encouraged to continue with the rescue operation now that he had learned that Japanese carriers were in the vicinity of the island.

When Pye received the message, “Enemy on island, issue in doubt” from Commander Cunningham, he came to the bitter conclusion that Wake could not be relieved. Pye’s order to recall the Wake relief force came as a shock to many around him, including Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, who gave the order from the bridge of the Saratoga to return to Pearl Harbor. Putnam and the remaining Wake Islanders were now left to fend for themselves.

After nearly six hours of continuous combat, planes from the Hiryu and Soryu continued to pound Wake’s remaining defensive positions. When the sun finally broke over the atoll, the silhouettes of several Japanese ships now appeared on Wake’s horizon; Admiral Kajioka had returned with greater numbers than his first attempted landing on the 11th.

At around 8 am, more than a thousand Japanese SNLF men were now on Wake, forcing Commander Cunningham to make the agonizing decision to surrender rather than needlessly sacrificing additional American lives. Major Devereux had a white surrender flag made and quickly contacted the Japanese, who then escorted Devereux and his aide, Sergeant Donald R. Malleck, around the atoll to direct Wake’s defenders to lay down their arms.

When Devereux and his surrender party reached Hanna’s gun—still being guarded by VMF-211—Putnam emerged from his position, bleeding profusely from his facial wound. Devereux remarked in his book, The Story of Wake Island, that Putnam “looked like hell itself … his face was a red smear.”

Putnam, Tharin, and Hanna were left under guard as Devereux made his way across the atoll to spread the grim news. By the late morning of the 23rd, all resistance had ceased. As the Japanese began questioning their new captives, Putnam, Tharin, and Lieutenants Kinney and Kliewer were singled out to be executed after SNLF men obtained a roster of VMF-211’s aviators. The Japanese were clearly incensed by the heavy losses that Putnam’s squadron had inflicted on them during the siege and were now thirsty for revenge.

On January 9, 1942, Putnam’s wife, Virginia, received the first of several letters from USMC Headquarters in Washington, D.C., indicating that her husband had been stationed on Wake when the Japanese attacked and was likely a prisoner of war. It would not be until October 1942 that she would receive a letter from him: “There is no way of saying how your letters buoyed me up,” he wrote, “and how much brighter the world looks now that I have heard from you and know that all of you are well.”

The Japanese herded Wake’s nearly 1,600 surviving military and civilian personnel to the airfield where SNLF guards were posted with machine guns at the ready. After the decision was made to spare the lives of Putnam and the rest of Wake’s garrison, the major was questioned by Japanese intelligence officers. Putnam’s extensive background in aviation and communications was of vital interest to the Japanese, but he refused to talk.

On January 11, Wake’s Marines and civilians were informed that they would be evacuated from the atoll aboard the Japanese liner Nitta Maru the following day.

Putnam and around 30 of Wake’s officers boarded the ship where they were shoved into a cramped space that once served as the ship’s mailroom. The men were not permitted to speak, and all valuables were confiscated. The civilians and enlisted men were then forced into the bowels of the ship where some endured savage beatings at the hands of their captors.

The Nitta Maru departed Wake Island on January 12, 1942, leaving behind those who were too sick or wounded to be moved along with a group of civilian contractors needed for future construction projects; 98 of these civilians were later executed on Wake by their Japanese captors on October 7, 1943.

After spending six tense days at sea, the Nitta Maru docked at Yokohama on January 18. Putnam was among 20 men who were taken off the ship for further interrogation. After the Nitta Maru left Yokohama for Shanghai with the remaining Wake Islanders, Putnam was sent by rail to the Zentsuji prisoner of war camp where he would spend the majority of his time as a prisoner of the Japanese Empire. Five Americans (three Navy men and two men from VMF-211) were later beheaded by the Japanese aboard the Nitta Maru as the ship was en route to Shanghai.

Arriving at Zentsuji on January 29, Putnam spent his first few weeks in captivity getting acclimated to his new surroundings. On March 7, Putnam began recording the daily events at Zentsuji in a series of diaries that were issued to him by his captors.

Over the next 3½ years, he vividly described the day-to-day life of a prisoner of war. Fortunately for Putnam and the other Wake Islanders, they enjoyed one of the highest survival rates among Allied prisoners who were captured by the Japanese during World War II.

The Zentsuji prison camp was located on the island of Shikoku and held American, British, Australian, and Dutch soldiers captured during the first months of Japan’s offensive operations across the South Pacific in late 1941 and early 1942.

Opening only a few weeks prior to Putnam’s arrival, Zentsuji was meant to be a “show camp” to demonstrate for the International Red Cross Japan’s “humane treatment” of Allied prisoners.

It was not until June 23, 1945, that Putnam was moved out of Zentsuji and transferred to Rokuroshi (Honshu Island) prison camp, where he spent the remaining three months of his captivity. Following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, respectively, supplies soon began reaching Rokuroshi from American planes. After nearly four years of captivity, a gaunt Paul Putnam returned home in September 1945.

His love of country and the Marines had not faded during his ordeal. In March 1946, he reported to the Marine Corps School at Quantico for senior course instruction at the Command and Staff School. He then served as deputy chief of staff with the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing, later becoming the commanding officer of Marine Air Group 14.

In October 1951, toward the end of his career, Putnam was transferred back to the West Coast when he was attached to Fleet Marine Force Pacific (FMFPAC) at the Marine Corps Air Station based at El Toro, California.

After a distinguished military career, Putnam rose to the rank of brigadier general upon his retirement in 1956.

In addition to receiving the Navy Cross for his actions at Wake, Putnam’s decorations include the Nicaraguan Cross of Valor, Purple Heart Medal (with star in lieu of a second), Presidential Unit Citation, Navy Unit Commendation, Nicaraguan Medal of Merit with star, Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal with “W” device, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, Air Medal with gold stars for his second and third awards, World War II Victory Medal, Prisoner-of-War Medal, Navy American Defense Service Medal, and the Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal.

An avid hunter, golfer, and fisherman, Putnam lived out his retirement surrounded by his wife and three daughters. Paul Albert Putnam died on May 21, 1982, in Mesa, Arizona, at the age of 78.

Paul Putnam’s legacy is one of humility and sacrifice combined with a strong and steady nerve. In a 1942 interview with the Mason City (Iowa) Globe-Gazette, Putnam’s wife Virginia described him as “the most placid, sensible human being I’ve ever seen. He could get along anywhere. He is so modest that other people have always had to tell me of his exploits before he would.”

Wake Island is currently under the jurisdiction of the Eleventh Air Force’s Pacific Air Force Regional Support Center (PACAF) and is strictly off limits to civilians. Inside Wake’s airport terminal building is the Wake Island Museum, which houses several artifacts and relics pertaining to the atoll’s storied history.

A prominent framed photograph of Paul Putnam hangs on a wall directly below a large wooden plaque with the famous Wake Island Avengers emblem depicting a lion over a map of the atoll. It is a fitting tribute to a leader of unparalleled courage and integrity.

Great stuff