By Michael D. Hull

If General Omar N. Bradley was “the GIs’ general,” then their best friend in World War II was undoubtedly a small, stringy reporter with graying red hair from Indiana who shared their foxholes and hardships while slogging across five battlefronts.

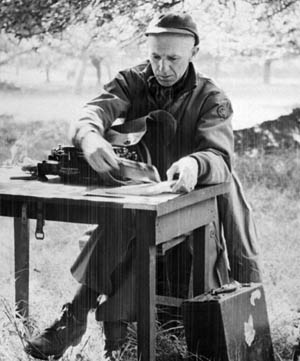

Writing six dispatches a week for the 13 million readers of 300 stateside newspapers from 1942 to 1945, Ernie Pyle offered a “worm’s eye view” of infantrymen, providing an essential link between America and its far-flung sons, brothers, and husbands. Focusing only rarely on the big picture involving generals and strategies, he recorded—with insight, clarity, and simple eloquence—the war of the foot soldiers, on the ground and on the move from Algiers to Normandy to Okinawa.

Pyle marched, ate, and slept with the riflemen, machine gunners, and mortarmen and was their champion. He listened to their fears, hopes, and jokes as they endured filth, hunger, boredom, wounds, and death. “I love the infantrymen because they are the underdogs,” he explained. “They are the mud-rain-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they learn to live without the necessities. And in the end they are the guys that wars can’t be won without…. All the war of the world has seemed to be borne by the few thousand front-line soldiers here, destined merely by chance to suffer and die for the rest of us.”

A “gentle soul” given to drinking, melancholy, and creative profanity, Ernie Pyle found no glory in war and decried its brutality whereby the boy next door was forced into becoming a trained killer. The former Hoosier farmhand, who narrowly escaped death twice, became America’s most widely read and famous war correspondent, wrote a best-selling book, and was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1944 for his frontline reporting.

Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, the first lady and a popular columnist herself, said she never missed reading Pyle’s dispatches, and A.J. Liebling of The New Yorker credited him with making “a large personal impress on the nation” during the 1939-1945 conflict. Poet Randall Jarrell said of the correspondent in The Nation, “There are many men whose profession it is to speak for us—political and military and literary representatives…. Pyle wrote what he had seen and heard and felt himself, and truly represented us.”

Novelist John Steinbeck observed, “There are really two wars, and they haven’t much to do with each other. There is a war of maps and logistics, of campaigns, of ballistics, armies, divisions, and regiments—and that is General [George C.] Marshall’s war. Then there is the war of homesick, weary, funny, violent, common men who wash their socks in their helmets, complain about the food … and lug themselves and their spirit through as dirty a business as the world has ever seen, and do it with humor and dignity and courage—and that is Ernie Pyle’s war. He knows it as well as anyone and writes it better than anyone.”

Ernest Taylor Pyle, the first and only child of sharecropper Will Pyle and his wife Maria, was born on Friday, August 3, 1900, at a farm near the small town of Dana on the western Indiana border. While the boy was a senior in high school, a neighborhood youth went off to fight in World War I, then raging in Europe. Ernie loved parades and patriotic songs, and, bored with the daily routines of farm life, he wanted to enlist, too. The distant conflict seemed like a romantic adventure to him. But his parents insisted that he finish school. After graduating, Ernie enrolled in the Naval Reserve, but the Armistice was signed in November 1918 before the young man could make it to advanced training.

In the autumn of 1919, Ernie entered the University of Indiana at Bloomington, where he studied journalism for 31/2years. Against his parents’ wishes, he dropped out in January 1923 to become a cub reporter on the La Porte Herald. After a few months, at the age of 23, the restless young man joined the Washington Daily News, a one-cent tabloid, and began a long association with the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. He showed a flair for writing catchy headlines and became a copy editor. Lee Miller, a fellow Hoosier, edited Ernie’s copy and encouraged him.

Ernie met his “ideal girl” in the form of civil service worker Geraldine “Jerry” Siebolds, who had moved to Washington from her native Minnesota. Bright, attractive, and nonconformist, she was willing to sympathize with Ernie in his periodic bouts of depression. Although Jerry had little use for marriage, they were wed by a justice of the peace in Alexandria, Virginia, on July 7, 1925. The couple lived a bohemian life in a modest, cluttered downtown Washington apartment.

In June 1926, Ernie and Jerry quit their jobs, pooled their savings, and bought a car, tent, and camp stove. They donned white coveralls and set off on a road trip around the country. After driving 9,000 miles in 10 weeks, they wound up in New York, where Ernie got a job on the copy desk at the Evening World and later the Post. Not fond of New York, he readily accepted an offer to become the telegraph editor at the Washington Daily News in December 1927. It was another desk job, but Ernie made sure there was time for writing. He started the first daily aviation column in American journalism at the time when Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh and other pilots were the nation’s heroes, and the Scripps-Howard chain eventually made him its aviation editor. He disappointed many fliers and readers in 1932 by becoming managing editor of the Washington Daily News.

The three-year stint there aged Pyle, and he suffered a severe case of pneumonia in the winter of 1934. He was granted a leave of absence, recovered, and talked his bosses into letting him try a new career as a roving columnist. He was to write six columns a week for the 24 Scripps-Howard newspapers. Through the following six years, the restive, curious Ernie was in his element.

Crossing the continent 35 times and touching each state more than once, he filed reports from Alaska, Hawaii, and Central and Latin America. He moved by car, truck, plane, boat, horse, and mule and interviewed all kinds of people, from Alaskan gold miners to a squatter artist who lived in a shanty behind the Memphis, Tennessee, city dump. Although inherently shy, Ernie had a gift for putting people at ease and opening up to him. Typing his columns with two fingers in hotel rooms, he churned out more than two million words during the Great Depression.

Jerry retyped the copy for his “The Hoosier Vagabond” column and offered him praise and criticism, but it was not a happy life. Both were often discontented with the traveling, Ernie became impotent, and Jerry showed signs of depression, drank heavily, used sedatives, and twice attempted suicide. The couple spent increasing amounts of time apart, with Jerry living sometimes with her mother or friends.

Ernie pushed for syndication outside the Scripps-Howard chain and found himself writing “silly dull columns” as the world situation worsened in the late 1930s. His work now seemed trivial, but he took serious notice when Great Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany on September 3, 1939. “Personally, I’m just about to bust,” he told his longtime university friend, Paige Cavanaugh. “I want to get over there as a war correspondent or something so bad…. Pacifism is fine as long as there ain’t no war around. But when they start shooting, I want to get close enough just a couple of times to get good and scared.”

Just over a year later, in mid-November 1940, Pyle headed for England to report on the aftermath of the Battle of Britain. Riding in a seaplane from neutral Lisbon, he arrived in mid-December for a three-month stay, just in time to witness brutal German firebomb raids on London. Wearing a trench coat and borrowed steel helmet, he reported from a balcony that the city was “stabbed with great fires, shaken by explosions, its dark regions along the Thames sparkling with the pinpoints of white-hot bombs.” He immersed himself in the life of London, recording for his many readers the daily sights and sounds of a great city under aerial siege. Of the air raid sirens he wrote, “To me, the sirens do not sound fiendish, or even weird. I think they’re sort of pretty…. In fact, it sounded exactly like the lonely singing of telephone wires on a bitter cold night in the prairies of the Middle West.”

Sometimes he showed a light touch, as when describing how one London hotel had set aside a separate area in its air raid shelter for chronic snorers: “They just herd ‘em all together and let ‘em snore it out.” His chatty, concise columns—well received in the United States—described nights in the crowded subway air raid shelters, the heroic work of London firemen and rooftop plane spotters, and the devastation of Coventry. He also interviewed wounded soldiers and told how the war was affecting people in the industrial cities, on farms, and in the coal mines from Birmingham to Edinburgh to Bristol. Ernie came to like England and admire the cheerful spirit of her people. “In three months,” he reported, “I have not met an Englishman to whom it has ever occurred that Britain might lose the war.”

Returning home in the spring of 1941, Pyle had to cope with the death of his mother in Indiana and a suicide attempt by his wife. Jerry recovered but started drinking heavily again. Ernie resumed his column stateside, and by the end of the year America was at war.

The year 1942 brought more troubles. Pyle had a brief platonic relationship with a woman in San Francisco and underwent nonproductive treatments for his impotence. Jerry’s drinking and general condition worsened, and Ernie reluctantly divorced her. He hoped that she would come “to face life like other people” and left open the possibility of remarriage. Meanwhile, Scripps-Howard alerted Pyle to prepare for a foreign assignment. He was granted a six-month extension from the draft and flew in mid-June from New York to Ireland, where the 34th Infantry “Red Bull” Division and other U.S. Army units were training. Welcomed by King George VI of England, the 34th Division was the first sent overseas in World War II.

In Ireland, Ernie began his unique association with GIs. He chatted with them, studied them, picked up on their longings and homesickness, and sent back the kind of detailed human interest dispatches overlooked by most other correspondents. His circulation figures rose, as did his frame of mind. He gained another draft extension and learned in the autumn of 1942 that the government had stopped calling up men aged 38 and above. He was free to experience the war as an observer, and he did not have long to wait.

Operation Torch, the complex, hastily planned Anglo-American invasion of North Africa, began on November 8 with landings in Algeria and Morocco. The following day, “feeling self-conscious and ridiculous and old in Army uniform,” Ernie left London and boarded the Rangiticki,an aging British troop transport. She was part of an 800-ship convoy carrying U.S. soldiers to Algeria. After dodging a pack of lurking German submarines outside Gibraltar, the convoy safely reached the port of Oran, and a relieved Pyle went ashore on November 22. “Like twine from a bidden ball, the ships poured us out on to the docks in long brown lines,” he reported. “We lined up and marched away. We marched at first gaily and finally with great weariness, but always with a feeling that at last we were beginning the final series of marches that would lead us home again.”

Ernie spent the rest of the year in and around Oran, writing about the GIs, Colonel William O. Darby’s Rangers, medics, Arabs, and a Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter squadron based at a desert airfield called the Garden of Allah. The correspondent was shocked when the pilots laughingly reported strafing enemy convoys and blowing the Germans out of their trucks “like firecrackers.” It disturbed him that young Americans could kill so readily and with relish.

Late in January 1943, Pyle joined up with the infantry of Maj. Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall’s II Corps, headquartered at Tebessa in Algeria near the Tunisian border. Riding by jeep to the Tunisian front lines, he got to know the commanders and their men. His reporting manner was unobtrusive. Wearing a GI woolen cap and usually smoking a cigarette, he mingled, listened, and rarely took notes. The result was that he gained the respect and friendship of all ranks. He endured the hardships and dangers of the tight-knit line battalions and companies and was able to report the war at its basic, grimmest level. Ernie spent a week or two in the frontline foxholes before withdrawing to type out his columns.

A letter from Jerry refusing his offer of remarriage left Ernie “so disappointed I almost felt like crying,” but he rallied. He found life at the front “so wonderfully simple” and invigorating. He was tanned and healthy; he had virtually stopped drinking, and his nerves were steady.

The U.S. Army matured in North Africa, and Ernie Pyle experienced it firsthand. He was with the II Corps on February 14, 1943, when German Afrika Korps panzers and infantry pushed it back 50 miles at Kasserine Pass in Tunisia. The poorly led, undisciplined Americans panicked, abandoned their weapons and equipment, and fled in disarray, forcing the British Eighth Army and other U.S. units to stabilize the situation. Kasserine was a humiliating blow to American morale, but the fumbling Fredendall was replaced by the fire-eating Maj. Gen. George S. Patton Jr., and the once cocky GIs learned bitter lessons swiftly.

Pyle wrote, “Apparently it takes a country like America about two years to become wholly at war. We had to go through that transition period of letting loose of life as it was, and then live the new war life so long that it finally became the normal life to us.” Among the GIs, Ernie sensed “a new professional outlook, where killing is a craft.” The American soldiers came to gain the respect of their seasoned British allies, who had questioned their fighting spirit and called them “our Italians.”

By early April 1943, Ernie found that he had become inured to battlefield carnage. “Somehow I can look upon mutilated bodies without flinching or feeling deeply,” he wrote. Yet he still had trouble sleeping after days of watching young men kill and be killed. “At last, the enormity of all these newly dead strikes me like a living nightmare,” he said. “And there are times when I feel that I can’t stand it all and will have to leave.” He would always hate the “tragedy and insanity” of war but reported, “I know I can’t escape and I truly believe the only thing left to do is be in it to the hilt.” Meanwhile, his stateside popularity was increasing. More newspapers were running his column, and Henry Holt & Co. offered to reprint his North Africa dispatches in book form.

As the British Eighth and U.S. First Armies pressed in on Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps and pushed toward the Mediterranean ports of Bizerte and Tunis, Pyle marched with Maj. Gen. Terry de la Mesa Allen’s 1st Infantry Division. Ernie did not write much about the brass, but “Terrible Terry” Allen was an exception. “Major General Allen was one of my favorite people,” he said. “Partly because he didn’t give a damn for hell or high water; partly because he was more colorful than most; and partly because he was the only general outside the Air Forces I could call by his first name. If there was one thing in the world Allen lived and breathed for, it was to fight…. He hated Germans and Italians like vermin, and his pattern for victory was simple; just wade in and murder the hell out of the low-down, good-for-nothing so-and-so’s.”

It was while he was with the Big Red One that Pyle wrote his most memorable columns of the North African campaign. With humanity and his keen eye for detail, he recorded the daily ordeals of the weary, dirty foot soldiers as they marched, fought, and endured shellings and dive bombings. To him, they were all heroes—ordinary men, not particularly brave, but who persisted in going forward because they had to do so.

“We’re now with an infantry outfit that has battled ceaselessly for four days and nights,” he reported. “This northern warfare has been in the mountains. You don’t ride much any more. It is walking and climbing and crawling country. The mountains aren’t big, but they are constant. They are largely treeless. They are easy to defend and bitter to take. But we are taking them….”

When soldiers of the U.S. First and British Eighth Armies linked up in Tunisia in April 1943, Ernie reported, “The men of the Eighth Army were brown-skinned and white-eye-browed from the desert sun…. Their spirit was like a tonic. The spirit of our own troops was good, but those boys from the burning sands were throbbing with the vitality of conquerors…. We envied them, and we were proud of them.”

By mid-May 1943, the Tunisian war was over and the German and Italian foes had surrendered by the thousands. Ernie ruled out a home leave and worked on a long essay that would be the last chapter of his book, Here Is Your War. In this remarkable piece of writing, he explained that the war in North Africa had been a severe but beneficial testing ground. The troops had been well cared for, their rations and medical facilities were good, and their weapons and equipment had been flawed but were being improved. The soldiers themselves, he noted, had been made harder and more profane.

On June 29, 1943, a year and 10 days after his arrival in Ireland, Pyle flew to Bizerte, boarded the USS Biscayne, a seaplane tender and headquarters ship, and made ready for his second combat voyage in eight months. Operation Husky, the massive British-American invasion of Sicily on July 10, found Ernie tired and sick. “I’m getting awfully tired of war and writing about it,” he admitted to Jerry. “It seems like I can’t think of anything new to say; each time it’s like going to the same movie again.” He persevered, and tagged along with the 120th Engineer Battalion of Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton’s 45th Infantry “Thunderbird” Division in northwestern Sicily. But the stoic little Hoosier was felled by “battlefield fever” and spent five days in a field hospital amid the “death rattle” of dying men. The five-week campaign fought by the British Eighth and U.S. Seventh Armies ended just after Ernie’s 43rd birthday, and he decided to go home for a break. He was exhausted.

Arriving in New York on September 7, 1943, four days after British troops invaded Italy, Pyle was besieged as a celebrity. Radio networks sought his services, 50 officers at the Pentagon questioned him, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson chatted with him, and Mrs. Roosevelt invited him to tea. Ernie’s book, Here Is Your War, had been published and widely acclaimed, and he autographed copies before leaving for Italy in late November 1943.

Within days, he was back with the dogface soldiers he loved, covering the bitter action as units of Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark’s Allied Fifth Army assaulted the Germans’ 10-mile-deep Winter Line in the rugged Apennine Mountains. Fought in the worst winter Italians had seen for many years, it was the toughest campaign Pyle had experienced. North Africa had been exciting, but the war in Italy debilitated all involved in it.

“The country was shockingly beautiful, and just as shockingly hard to capture from the enemy,” Ernie reported while with an artillery regiment. “The hills rose to high ridges of almost solid rock. We couldn’t go around them through the flat peaceful valleys, because the Germans were up there looking down upon us, and they would have let us have it. So we had to go up and over…. Our troops were living in almost inconceivable misery. The fertile black valleys were knee-deep in mud. Thousands of the men had not been dry for weeks. Other thousands lay at night in the high mountains with the temperature below freezing and the thin snow sifting over them. They dug into the stones and slept in little chasms and behind rocks and in half-caves. They lived like men of prehistoric times, and a club would have become them more than a machine gun….”

Early in January 1944, Pyle hitched up with the 36th Infantry “Texas” Division, which was soon to get mauled in a tragic, failed attempt to cross the Rapido River. While with the Texans, he wrote the most moving column of his career, hailed as a classic of World War II dispatches. It recounted with powerful simplicity the death of young Captain Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas, a gentle and beloved company commander, near San Pietro.

Ernie told how the soldiers waited for their captain’s body, lashed to the back of a mule, to be brought down a mountain trail: “One soldier came and looked down [at the body], and he said out loud, ‘God damn it.’ That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, ‘God damn it to hell, anyway’…. Another man came; I think he was an officer…. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive. He said, ‘I’m sorry, old man’…. Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said, ‘I sure am sorry, sir.’” The column was a sensation in America, and the Washington Daily Newsdevoted its entire front page to it. The death of Captain Waskow was later dramatized in an acclaimed Hollywood film, The Story of G.I. Joe, based on Pyle’s best-selling collection of dispatches, Brave Men.

Vivid reports of the action around San Pietro were also filed by Homer Bigart of the New York Herald-Tribune, and John Huston depicted the battle in an award-winning documentary film.

Pyle filed his last reports on the Italian campaign in March-April 1944 from the Anzio-Nettuno beachhead, where British and American forces were hemmed in for four bitter months. “On this beachhead, every inch of our territory is under German artillery fire,” he wrote. “There is no rear area that is immune, as in most battle zones. They can reach us with their 88s, and they use everything from that on up…. I’ve been weak [in the joints] all over Tunisia and Sicily, and in parts of Italy, and I get weaker than ever up here.” At Anzio, Ernie narrowly escaped death with a cut on his cheek when a 500-pound bomb blasted a waterfront villa where he lived with other correspondents.

Early in April, Pyle boarded a hospital ship bound for Naples and then flew to North Africa and London. Shortly after arriving in the British capital, word came that he had won a Pulitzer Prize for “distinguished war correspondence” in 1943. He was surprised and elated. Then came the long-awaited Allied invasion of northern France, but Ernie’s confidence had taken a beating, and he was apprehensive. “I have an awful feeling that I won’t live through this one,” he confided to a fellow correspondent. “It’s a terrible feeling. I can’t sleep, and it is like a constant weight, night and day.”

But he steeled himself and left to cover the big show, landing at Omaha Beach in Normandy on June 7, 1944. He wrote pieces on the antiaircraft gun crews protecting the beachheads and reported, “It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore. Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever. Men were floating in the water, but they didn’t know they were in the water, for they were dead. On the beach lay, expended, sufficient men and mechanism for a small war. They were gone forever now. And yet we could afford it….”

Ernie spent time with the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions and then accompanied Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy’s 9th Infantry Division in its assault on Cherbourg. The correspondent narrowly escaped death for the second time when American bombs fell short during the breakout west of St.-Lo on July 25, and he rode a jeep into Paris when General Jacques Philippe Leclerc’s French 2nd Armored Division liberated the capital on August 25. The city’s tumultuous celebration buoyed Ernie’s spirits, but he told his 13 million readers, “I have had all I can take for a while.”

He sailed to New York in September and found himself again under siege. Interviews and autographs were sought, John Steinbeck and Helen Keller wanted to talk to him, he sat for a bust by sculptor Jo Davidson and was profiled by Lifemagazine, and Hollywood producer Lester Cowan needed to discuss The Story of G.I. Joe,then in production. Ernie foiled another suicide attempt by Jerry, and she underwent shock therapy while he accepted several honorary degrees. He planned a trip to the Pacific War zone, although he admitted, “I feel that I’ve used up all my chances.” He visited the set of his film biography, and he and Jerry danced at Ciro’s, the Hollywood nightclub, on their last night together. Then, on the evening of New Year’s Day, 1945, Pyle headed for Camp Roberts, California, on the first leg of his journey to the Pacific.

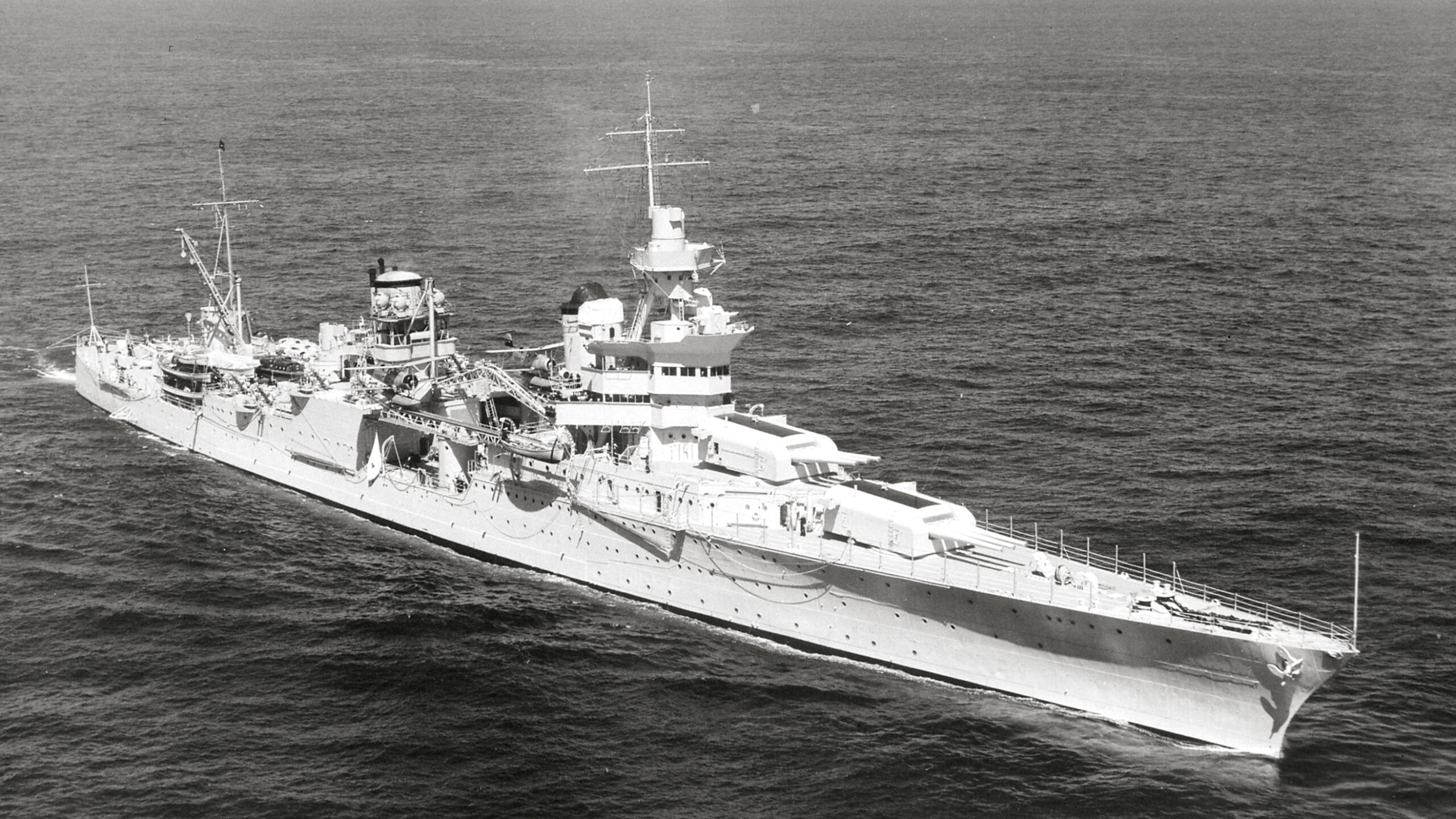

After being greeted by a 50-piece band and 1,000 cheering soldiers at the San Francisco port of embarkation, Ernie sailed to Hawaii and the Mariana Islands, where he filed several dispatches on the Boeing B-29 heavy bomber groups that were hammering Japan. He then reported from aboard the aircraft carrier USS Cabot and sailed from the great naval base at Ulithi in the Caroline Islands to Okinawa with units of the 1st Marine “Old Breed” Division. Ninety minutes after the big invasion began early on April 1, 1945, Pyle went ashore with men of the 5th Marine Regiment. He wrote columns about the leathernecks for the first time.

Ernie saw little action with the Marines and soon rejoined the Army dogfaces he loved. He was welcomed on April 17 by Maj. Gen. Andrew D. Bruce’s 77th Infantry “Liberty” Division, which had landed two rifle regiments on tiny Ie Shima Island, four miles west of Okinawa, on the previous day. “The front does get into your blood, and you miss it and want to be back,” said Ernie. He hitched up with the 305th Regiment, but time had run out for the heroic Hoosier.

On the morning after joining up with the 77th Division, he was riding in a jeep when it was hit by Japanese machine-gun fire. Ernie dived into a ditch, and the firing stopped. But when he looked up to see what was happening, he was shot in the left temple. He was 44 years old. Saddened GIs hastily erected a crude wooden marker reading, “At this spot, the 77th Infantry Division lost a buddy Ernie Pyle 18 April 1945.”

Chaplain Nathaniel B. Saucier of the 77th Division’s 305th Infantry Regiment conducted a simple burial service on Ie Shima and mourned the death of a “noble man now departed.” Ernie’s body was eventually reburied in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii’s Punchbowl Crater.

The loss jolted a nation still mourning the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt six days before. His successor, President Harry S. Truman, said, “The nation is saddened again by the death of Ernie Pyle,” and proposed a special congressional medal and the christening of a troop transport in his name. War Secretary Stimson expressed “great distress,” Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal said the country owed Pyle its “unending gratitude,” and General Bradley commented, “I have known no finer man, no finer soldier, than he.” Young frontline cartoonist Bill Mauldin, whose syndication Pyle had promoted with the aid of Mrs. Roosevelt, said, “The only difference between Ernie’s death and the death of any other good guy is that the other guy is mourned by his company. Ernie is mourned by his army.”

The Story of G.I. Joe had its world premiere on July 6, 1945, and was hailed as a masterful depiction of the U.S. infantry in North Africa and Italy—stark and honest, yet sensitive and poignant. General Dwight D. Eisenhower called it “the greatest war picture I’ve ever seen.”

Pyle had requested that Burgess Meredith portray him, and the veteran actor gave a superb performance, as did Robert Mitchum in the role of Captain Waskow. The film brought Mitchum his only Oscar nomination. The director was William Wellman, who crafted such other screen classics as Wings, The Public Enemy, A Star Is Born, Beau Geste, The Ox-Bow Incident, Buffalo Bill, and Battleground.

Ernie Pyle was not a great writer, but an unpretentious craftsman. In simple, declarative sentences, he reported the brutal reality of infantry war as few other correspondents did. And he probably saw more action than any of them.

Frequent contributor Michael D. Hull has written for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments