By Arnold Blumberg

When plans were drawn up for the Allied invasion of France in 1944, one important consideration was securing a deep-water port to allow reinforcements and supplies to be brought in directly from Great Britain and the United States. Cherbourg, at the northern tip of the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy, was the closest such port to the landing sites, and planners consequently decided that the U.S. First Army’s main task after D-Day would be to capture Cherbourg and its harbor as quickly as possible.

The task of taking Cherbourg fell to the First Army’s VII Corps, under Maj. Gen. Joseph Lawton Collins. Nicknamed “Lighting Joe” for his ruthless pursuit of Japanese forces during the Guadalcanal campaign, when he commanded the 25th Infantry Division, Collins initially intended to advance on Cherbourg directly after landing at Utah Beach. If Cherbourg could be taken swiftly, it might not be necessary to completely seal off the peninsula in a time-consuming attack across its base. Unfortunately for the Allies, stubborn German resistance, abetted by difficult terrain and poor performance by some green American combat units, prevented the fall of the city immediately after the Normandy landings.

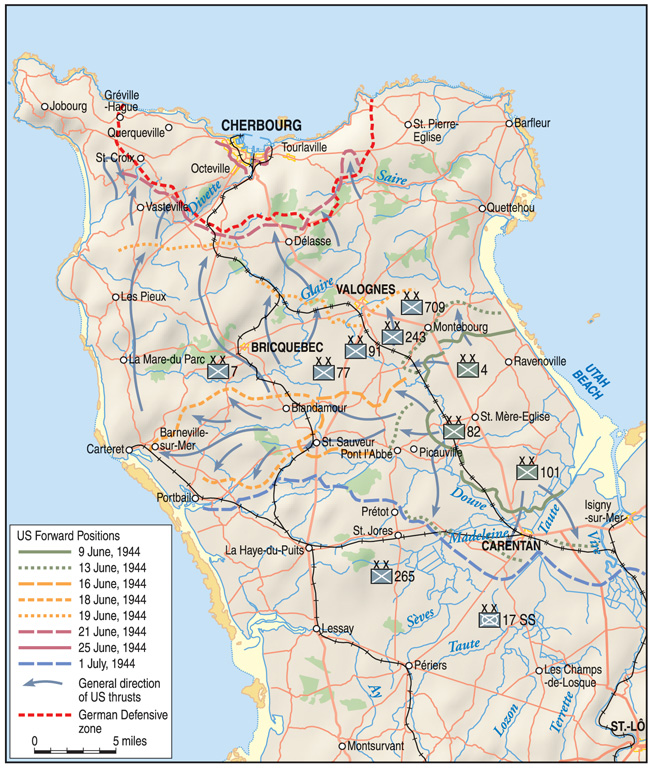

On D-Day+1, priority was given to linking the V and VII Corps. The flooded Douve River Valley was crossed on June 9, and the city of Carentan was secured nine days later by the 101st Airborne Division following an eight-day struggle against tenacious resistance from the German 6th Parachute Regiment. The fall of Carentan gave the Allies a continuous front from which VII Corps could begin its drive on Cherbourg. However, the fierce fighting around the town, combined with the strong German defensive ridgeline positions between Quineville, located on the east coast of the peninsula, and Montebourg, southwest and farther inland, prompted the American high command to shelve the original plan to advance northwest on Cherbourg directly from Utah Beach via the Carentan-Valognes-Cherbourg axis. Instead, the decision was made by First Army commander General Omar Bradley to push due west, splitting the enemy forces on the Cotentin and isolating Cherbourg in the process.

Cutting Off the Germans at Cherbourg

The new drive would originate from the bridgehead the 82nd Airborne Division, under Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, had gained on the west bank of the Merderet River at La Fiere. The 90th Infantry Division would reinforce the 82nd. Opposing the Americans were the Wehrmacht’s 243rd and 709th Infantry Divisions and the 91st Airlanding Division of General Erich Marcks’s LXXXIV Corps. The 11,529-man 243rd had been reinforced before the invasion with additional field artillery and mortars and contained potent self-propelled assault gun units. To enhance its mobility, two of its three grenadier regiments were equipped with bicycles.

The 709th Division, also with three grenadier regiments, had a manpower compliment of 12,320 troops. With few trucks and bicycles to transport its personnel, the division was charged with manning Cherbourg proper as well as the fortifications in the eastern Cotentin. The 91st Airlanding Division’s two grenadier regiments, totaling 8,000 men and supported by a poorly equipped artillery regiment, were based in the northern Cotentin at the start of the Allied invasion. Rounding out LXXXIV Corps’ defenders were several independent units, including the Seventh Army Assault Battalion, two motorized artillery battalions, the 902nd Assault Gun Battalion, and the 206th Panzer Battalion equipped with French Somua and Hotchkiss tanks.

On June 9, concerned over the threat of a breakthrough to Cherbourg, German commanders ordered the 77th Infantry Division, then coming up from Brittany, to proceed to Valognes, southeast of Cherbourg. The understrength 77th (10,000 men in two grenadier regiments) sported a mere 16 field artillery pieces and 12 heavy antitank guns. Only two of its infantry battalions would fight northwest of Utah Beach; a third was attached to the Cherbourg garrison inside the city.

For the next several days the Americans pushed forward as planned. The 4th Infantry Division, coming from Utah Beach, took the Quineville ridgeline to the east and west of Montebourg, but the town of Montebourg remained in German hands. Meanwhile, the poorly led U.S. 90th Infantry Division crept forward beyond La Fiere. On the 14th, the newly landed 9th Infantry Division, in cooperation with the veteran 82nd Airborne, passed through 90th Division and drove toward the Douve River. At the same time, the 90th Division pivoted north to guard the 9th’s right flank.

Each American infantry division in the Cotentin had an authorized strength of 15,000 men in three infantry regiments. The divisions were fully motorized and supported by four artillery battalions, a tank battalion, several tank destroyer companies, and combat engineer units. The diverse terrain in the battle zone, however, did much to cancel out American superiority in men and material. The American forces had to fight through the gnarled and rugged bocage (hedgerows) in the central and southern Cotentin, the less-wooded ground in the north, the open terrain around Cap de la Hague, and finally the urban streets of Cherbourg itself. Any sprint to the west to cut off the peninsula had to contend with the Douve River, which, although not overly wide or swift-running, flowed through low-lying, marshy territory. Making the task even more difficult, the area between Carentan and St.-Sauveur-de-Pierrepont was filled with water meadows and swampland that further impeded movement and narrowed attack frontages.

Added to the difficult ground the Americans had to contend with, the units engaged in the peninsula were a mixture of untried (4th, 90th, 79th ) and tried (82nd Airborne, 9th ) divisions whose previous combat experience, or lack thereof, greatly affected their performance during the Cherbourg campaign. Despite the troublesome terrain and lack of battle experience of some of the American units, the move to cut off the peninsula from enemy reinforcements and to prevent German forces escaping south got under way on June 14.

The Plan to Take Cherbourg

By June 16, the 82nd and 9th Divisions, using two regiments apiece as their leading assault forces, crossed the Douve near the town of St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte. The next day two battalions of the 47th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, secured the area around St.-Lo-d’Ourville near the west coast, and by the 18th the Cotentin was effectively sealed off by VII Corps. The only sour note to the conclusion of the operation was the escape of 1,400 Germans out of the peninsula, mostly from the 77th Division’s 1050th Grenadier Regiment under divisional chief Colonel Rudolf Bacherer, which slipped through the American cordon near St. Lo on June 19 with most of their equipment and 100 recently captured American prisoners.

With the Cotentin cut off from the rest of German-occupied France, Bradley and Collins devised a plan to take Cherbourg using three divisions in a line-abreast formation: 4th Division on the right, 79th Infantry Division in the center, and 9th Infantry Division on the left flank. Along with the tank and tank destroyer units normally assigned to each infantry division, additional armor support was to be provided by the two squadrons of the 4th Cavalry Group. Besides the organic divisional cannon battalions, a score of 105mm and 155mm heavy artillery battalions from VII Corps and First Army would lend a hand in the reduction of Fortress Cherbourg. This was not the original plan to take the city, which involved just the 4th and 90th Divisions. The disorganized and fragmented state of the enemy forces, the recent disappointing performance of the 90th Division, and the availability of the fresh 79th Infantry, spurred the two officers to formulate the new scheme.

On the eve of the American attack, the Germans’ Cherbourg garrison was estimated to number 25,000 men. Another 15,000 enemy combatants were expected to be added in the form of refugees from the fighting that had taken place between the Allied landings at Normandy and the isolation of the peninsula by the Americans. Most of the German defenders were thought to be Luftwaffe and naval personnel, antiaircraft crews, and Todt Organization workers.

If the attackers did not know the exact number of their opponents, they did have very good intelligence about the Germans’ defensive lines, strongpoints, and overall fortifications. This vital information was derived from pre-invasion aerial photoreconnaissance, intelligence from the French Resistance, and recently captured German field orders that contained great detail about the layout and makeup of the Cherbourg defensive perimeter.

The Great Storm on the D-Day Beaches

At midnight on June 18-19, a strong northeast wind and heavy rains began to blow across the Normandy assault beaches. What would become known as the Great Storm lashed the coastal area for the next two days, preventing the offloading of men and material onto the beach. By the time the wind and torrents of rain abated on the 22nd, artificial harbor Mulberry A at Omaha Beach was too badly damaged to be used. The logistical disaster at Omaha renewed the imperative for the early capture of a deep-water French port to sustain the enormous amounts of troops, weapons, and supplies that the Allies needed to keep their toehold on the Continent and liberate France.

By June 22, VII Corps had surrounded the land side of the port of Cherbourg, which sat on the northern tip of the Cotentin Peninsula. The capture of the city’s vital harbor was now the first priority of Collins and his men. Their task would be made easier by the able assistance of the United States Navy. A few days earlier, Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo, in charge of all bombardment support ships in the American invasion sector, had offered Collins his help. The plan was for the Navy to neutralize German coastal artillery along the northern and eastern horns of the peninsula. The many enemy targets there included 20 casemated batteries ranging in caliber from 150mm to 280mm. In addition, there were many other German batteries of 75mm and 88mm, some of which could be trained inland as well as out to sea.

The gale that devastated the landing beaches also scattered Deyo’s vessels back to the British Channel ports. As a result, the Navy could not gather its strength for an effective fire support role until June 25. At 4:40 am, Deyo’s bombardment force departed England for Cherbourg. It was divided into two groups. Group I, under Deyo, included the battleship USS Nevada, the cruisers USS Tuscaloosa and Quincy, and British HMS Glasgow and Enterprise, as well as six destroyers. Group 2, under Rear Admiral C.F. Bryant, included the battleships USS Texas and Arkansas, and five destroyers. American and British minesweepers led the way.

Bombardment from the Sea

The bombardment force reached the French coast 15 miles north of Cherbourg at about 9:40 am, steaming in two parallel columns. Collins had asked Deyo that morning not to fire unless his ships were fired upon first. Collins was concerned that his infantry, then on the outskirts of Cherbourg, might be mistakenly hit by friendly naval fire. As noon approached, the fleet had not yet fired a shot. That changed after the vessels were fired at by the four German 150mm guns situated at Querqueville, three miles west of Cherbourg. The ships were then about 15,000 yards offshore.

Aided by RAF Spitfire reconnaissance aircraft, a spirited two-hour duel erupted between Deyo’s column and the Germans’ Querqueville battery, during which time HMS Glasgow received two hits. By 2:40 pm, the battery had apparently been silenced after Allied cruisers dropped 318 6-inch shells on it. Amazingly, as the Allied ships retired from Cherbourg later in the day, the German guns delivered a few more rounds in their direction. Fortunately for the Allies, the battery’s endurance was matched by its failure to score many hits on its targets.

In the meantime, Nevada and Quincy responded to onshore fire-control requests to target enemy positions two miles southwest of Querqueville as well as other targets of opportunity. Nevada unloaded 112 14-inch and 985 5-inch rounds that day. To the west, the injured Glasgow engaged a battery of four 155mm guns near the village of Gruchy. After shooting 54 rounds, the enemy temporarily ceased firing but came back to life later and traded shots with Glasgow and the destroyer Rodman.

While Deyo’s ships fought the German batteries to a draw west of the city, some lucky shots from the heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa managed to inflict injury on enemy positions within Cherbourg itself. As she withdrew from the battle zone, Tuscaloosa targeted two positions near Cherbourg’s dock, close to its fortified naval arsenal. One 75mm concrete gun emplacement was destroyed and another damaged by Tuscaloosa’s 8-inch armor-piercing shells.

Dueling With Battery Hamburg

While Deyo’s ships were challenging the German batteries to the west of Cherbourg, Bryant’s task force dueled with Battery Hamburg, located on a hill near Fermananville, a short distance inland from Cap Levi and about six miles east of Cherbourg. The site’s four 280mm, 11-inch guns were well separated, protected by steel shields similar to naval gun turrets, and reinforced by concrete casemates. Surrounding the coastal pieces were six 88mm, six heavy, and six light antiaircraft guns. The 11-inch monsters were crewed by German naval personnel and had a range of 40,000 yards. However, sighted to cover the sea approaches to Cherbourg, the battery could not fire east of a line running 35 percent true.

Bryant’s plan was to have Nevada with her 14-inch guns engage the target from extreme range—about 40,000 yards. In the meantime, Texas and Arkansas, whose weapons could fire only at a maximum range of 20,000 yards, would approach from the blind side to the east, wait for Nevada to silence the enemy cannons, and then finish off the German position. Unfortunately, Nevada was ordered away from Cap Levi, and the job of fighting Battery Hamburg was left to the two antiquated battleships.

A little after noon, Arkansas closed the range to 18,000 yards and opened fire. The Germans responded and hit the destroyer USS Barton with a dud shell that ricocheted from the water into her hull. At 12:32 pm, the destroyer USS Laffey took a 240mm round on her port bow. This too was a dud. Captain Julius Becton ordered his crew to throw the spent 400-pound shot overboard. Before doing so, they discovered Czech markings on the shell, surmising that the round may have been sabotaged during production by Czech partisans. If so, the anonymous act may have saved the ship from great damage or destruction.

The action now became general, with four destroyers and the battleship Texas joining in, the latter delivering three salvos, with each individual round weighing 1,275 pounds. For her trouble, Texas received in return a three-gun straddle across her bow, with three more shells passing over her stern a few minutes later as she turned full right rudder. More shells started to fall around her every 30 seconds. The fire seemed to be coming from a knoll 400 yards northeast of Battery Hamburg, so Texas’s captain, Charles Baker, directed his ship’s fire at that point.

At 12:51 pm, a shell from the German guns exploded on the deck of the destroyer USS O’Brien. Sustaining numerous near-misses on his battlewagons, Bryant ordered Texas and Arkansas to move north and widen the range between them and the coast. For the next 30 minutes, Arkansas concentrated her gunnery on four 105mm field pieces embedded in casemates. With the help of air and ground spotting, 22 shells silenced the target. Meanwhile, Texas took on Battery Hamburg. An enemy 280mm shot exploded near the bridge, killing helmsman Chris Christianson and wounding 11 other crew members. Captain Baker, also on the bridge, was hurled to the deck but not injured. Texas continued firing without a pause and soon gained her revenge when a shell pierced the iron shield of one of Battery Hamburg’s four guns and knocked it out of action for good.

Around 1:30 pm, the cruiser USS Quincy joined the fray against Battery Hamburg, her effort lasting for about an hour and a half before she was called away to support the action against Querqueville. For the rest of the afternoon, Texas and Arkansas divided their fire between Hamburg and the nearby 105mm gun battery, both keeping a distance of 20,000 yards between them and the German guns. Each time Texas strayed closer to Hamburg, she attracted a blistering fire from the battered German cannons. After hitting the German position at Hamburg with 206 14-inch shells from Texas, 58 12-inch shells from Arkansas, and 552 5-inch shots from the destroyers, the vessels were ordered back to England at 3 pm.

The Ground Assault Begins

The VII Corps attack on Cherbourg started in the early morning hours of June 19, with the 9th Division driving for the high ground between the towns of Rauville-la-Bigot and St.-Germain-le-Gaillard. The 79th Division, after passing through the 90th, headed for the ridges west and northwest of Valognes. Both units engaged the enemy south of Cherbourg on terrain dominated by hilly country and well suited for defense. On the right, the 4th Division advanced north to Montebourg.

The advance of the 4th Division to the west and east of Montebourg ran into effective resistance from elements of the German 709th Division and the Seventh Army Assault Battalion, about 1,500 men in all. After 10 hours of heavy fighting, the Germans retreated, yielding Montebourg to the Americans. Losses on both sides were moderate considering how long the fight had lasted.

On the 9th Division front, progress was much faster with the division advancing by nightfall a few miles beyond its original day’s objectives. In the American center, the 79th made slow progress but was unable to sever the Cherbourg-Valognes highway in the face of the determined enemy stand. The VII Corps advances for the day brought the Americans four miles south of Cherbourg.

On June 20, VII Corps advanced again against an opponent who increasingly disengaged and retreated into Cherbourg proper. The Americans seized Valognes and started to take up positions on the high ground around Cherbourg. The German defensive line confronting the attackers looked impressive: roads were blocked by barriers, and towns and hills comprising the outer fortress perimeter were laced with blockhouses, strongpoints, barbed wire, and trenches. Fortunately for the attackers, the German defenders of the apparently formidable positions were ill-trained, ill-equipped, demoralized, immobile, and not organized to fight sustained actions. Regardless, as the Americans probed the German defenses on the 21st they were met with spirited responses. By the end of the day, however, the city had been cut off from the eastern portion of the peninsula by elements of the 4th Division.

The town was now invested on all sides, with its outer works being pummeled by massive American artillery fire. Collins sent a formal demand for the city’s surrender to the German fortress commandant, Lt. Gen. Karl Wilhelm von Schlieben. With only 56 days of supplies left to sustain the garrison and no hope of succor from the outside, but fully cognizant that Adolf Hitler expected him and his men to hold on to Cherbourg for as long as possible, Schlieben refused Collins’s ultimatum.

Air Strikes on Cherbourg

June 22 saw the Americans renew their attack on the city, starting with a massive if not particularly effective aerial bombardment. As the planes headed back to base, the infantry of VII Corps took up the fight once more. The 4th Division advanced from the east, but its progress was slow against heavily fortified positions until friendly tanks were brought up to demolish the enemy strongpoints with cannon fire. Meanwhile, the 79th Division in the corps’ center moved along the Valognes-Cherbourg Road, aiming to take Fort du Roule and the high ground south of the city. The unit made slow but steady progress before halting for the night. To the southwest, the 9th Division reached the small hamlet of Nouainville, threatening the integrity of the German main line of resistance and forcing the enemy to throw in its last reserves to stop the American attack in this sector.

The tactic employed by the Americans on the 22nd was to bypass all heavily defended areas to keep up the momentum of the advance. This caused predicable problems, since German soldiers who remained behind American lines were able to disrupt the movement of supplies to the forward units. Dozens of mop-up operations had to be carried out to dislodge snipers and pockets of enemy resistance in the rear. This took time and prevented needed reinforcements, food, and ammunition from reaching the forward elements of the American advance.

June 23 began with terrific American air and artillery shelling of the Cherbourg garrison, which now had been whittled down to 21,000 men. Ammunition was running low and the all-important antitank ordnance needed to counter the rampaging American armor was almost gone.

By the next day, the Americans were bumping up against the city’s outskirts, having cleared or bypassed the shrinking defensive arc surrounding Cherbourg on its landward side. By the evening of the 24th, the 12th Infantry Regiment had gained a vantage point overlooking the city from the east and captured 800 prisoners in the process. In the center, regiments of the 79th (Cross of Lorraine Division), under rain and mist, were grinding forward through many enemy pillboxes, with the 313th Regiment capturing German soldiers and artillery along the way. The 314th Regiment strove to make its way to Fort du Roule, aided by air strikes by American Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers. On the left flank, the 9th Division slowly penetrated the southwest suburbs of the city, overrunning three Luftwaffe flak units as they went forward.

Collapse of Command and Control

Although the German defense was crumbling due to battle casualties, plummeting morale, and the loss of officers and NCOs, it was doing so slowly. The urban combat environment allowed for small numbers of defenders to hold up larger groups of attackers. The Germans took advantage of the situation to do the maximum damage to the port facilities before the inevitable fall of Cherbourg. At the same time, German leaders in the city hoped to inflict as many losses on the Americans as possible.

On June 25, part of Fort du Roule, the southeast gateway to the city, fell to the 314th Infantry Regiment, 79th Division. Supported by P-47s, the regiment’s 3rd Battalion overcame the position. During the attack, 1st Lt. Carlos O. Ogen, leader of K Company, won the Medal of Honor for destroying an 88mm naval gun emplacement and several enemy machine-gun nests with rifle and hand grenades after being twice wounded. That day also saw the 9th Division capture Fort Equeurdreville at the city’s western corner. The tally of prisoners taken by the division on the 25th was more than 1,100 men. Meanwhile, the 4th Division closed on the east and southeast sides of Cherbourg.

As the battle raged on, the breakdown of communications between the beleaguered city commanders and their higher-ups left scattered Wehrmacht units without control or information and made them easy marks for appeals to surrender. The Americans took full advantage of the situation to avoid dangerous street fighting by broadcasting requests for their enemy to give up, promising food, medical attention, and a return to the Fatherland at war’s end.

The morning of June 26 saw two of the 79th’s regiments reach Cherbourg harbor. As the light of day faded, that part of Fort du Roule still in German hands surrendered. So, too, did the fortress leader, Schlieben, and 850 other Germans sheltering with him. Requests by Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, 9th Division commander, as well as Collins, to surrender the rest of the Cherbourg garrison were refused by the proud German officer.

Surrender of the German Army

Around 10 am on the 27th, the last organized defenders in Cherbourg, those holed up in the formidable naval arsenal in the southern part of the city, gave up after the arrival of an American tank at the building’s front entrance. Between 400 and 800 Germans were taken into custody, including deputy fortress commander Maj. Gen. Robert Sattler. The last organized German force northeast of Cherbourg, 1,000 men under Major Wilhelm Kuppers, surrendered to 4th Division commander Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton on the 28th. The next day, Fort de l’Quest in Cherbourg harbor and its 30 defenders surrendered.

As Cherbourg fell piece by piece, the 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Division, and the 4th Cavalry Group bottled up 6,000 German soldiers and sailors (no more than 1,000 of whom were trained in ground warfare) under Lt. Col. Gunther Keil in the Cap de la Hague area, 20 miles west of Cherbourg. At the same time, the 22nd Regiment, 4th Division, fought to capture Cap Levi and its coastal artillery battery to the east of Cherbourg.

On June 29, the 9th Division’s 47th and 60th Regiments, after two heavy bombardments with artillery and mortars, attacked the German defenders on the Cap de la Hague Peninsula. The next day the main enemy line was breached, and Colonel Keil and his staff were captured. The fighting on the peninsula ended on July 1 with the capture of 3,000 prisoners.

2,826,740 Tons of Cargo

In the fight for Cherbourg, VII Corps sustained 2,800 killed in action, 13,500 wounded, and 5,700 missing. The city was captured on D-Day+21, six days later than the Allied pre-invasion planners had envisioned. German losses were 39,000 captured in addition to an undetermined number of killed, wounded, and missing.

By the time Cherbourg fell to the Americans, the port had been totally demolished and mined by the Germans. American Seabees and Navy salvage ships and crews worked around the clock to restore the harbor to operational capacity. On July 16, the first freight was discharged at the port; by September, more than 17,000 tons of material were being offloaded daily. Two fuel pipelines were operating as well. By the fall of 1944, Cherbourg had become second only to Marseilles as the main point of entry for supplies to the U.S. Army in Europe. By war’s end, a staggering 2,826,740 tons of cargo had been unloaded there, in addition to 130,210 personnel entering the combat theater via the port.

The fall of Cherbourg presaged the ultimate triumph of the Allies. It allowed them to build up an irresistible superiority in men and supplies that would make their breakout from Normandy and subsequent sweep through France and Germany possible.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments