By Herb Kugel

On June 7, 1944, D+1, two volunteer Canadian 3rd Division, 9th Infantry Brigade regiments, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders (the North Novas) and the 27th Canadian Armoured Regiment (the Sherbrooke Fusiliers)—together with volunteer units from the Camerons of Ottawa and Forward Observers from the 14th Field Regiment—fought an important but now generally forgotten battle in Normandy.

Forgotten or not, the outcome of this battle can be considered to be a significant factor in preventing a planned German attack into the D-Day landing beaches that could have split the Allied invasion force in two.

Juno Beach: Canada’s D-Day Landing Zone

In June 1944, the Canadian military was a completely voluntary force; there was no conscription in Canada. The Canadian Army consisted of 405,834 men and women who had volunteered for General Service. Of these volunteers, only about 100,000 men were in the First Canadian Army, which was preparing for its role in Operation Overlord, the D-Day invasion of Normandy.

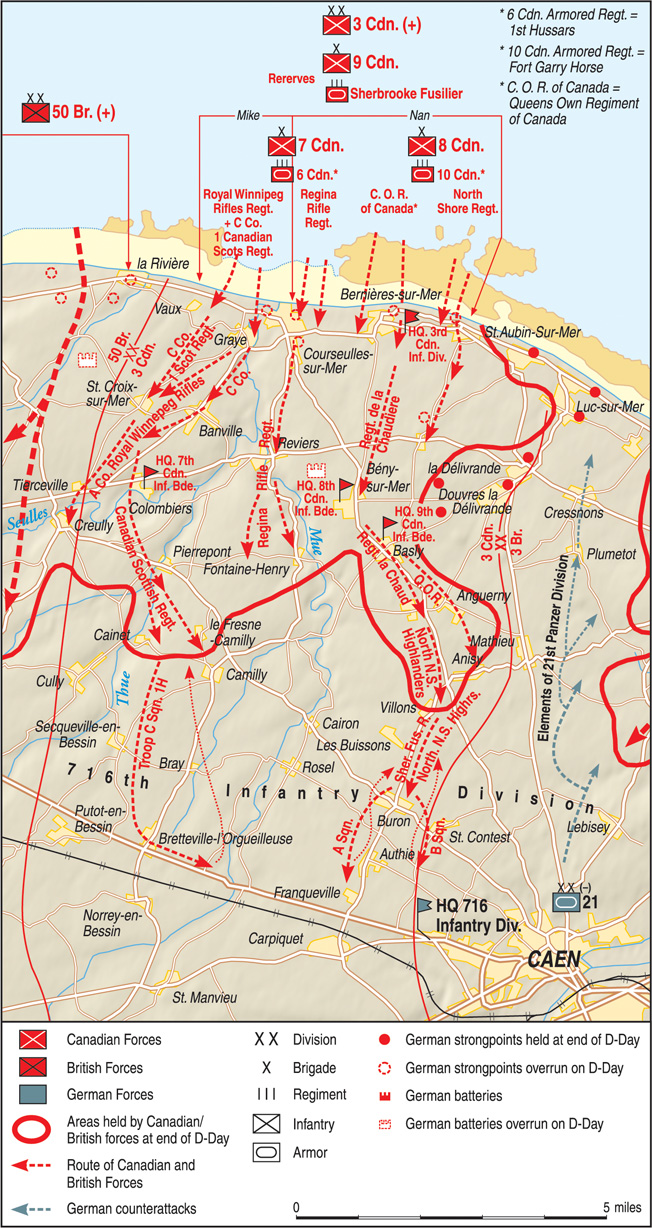

From west to east, the Allies’ beachheads were code-named Utah (to be initially assaulted by the 4th U.S. Infantry Division), Omaha (1st U.S. Infantry Division with a regiment of the 29th Infantry Division attached), Gold (50th British Infantry Division), Juno (3rd Canadian Infantry Division), and Sword (3rd British Infantry Division). Utah and Omaha were the responsibility of the American First Army, while the three other beaches were the responsibility of the British Second Army. All told, these five beaches comprised an invasion sector more than 50 miles long. Three airborne divisions (the U.S. 82nd and 101st, and the British 6th, which included a Canadian airborne battalion), with glider components, would arrive before the seaborne landings took place to seal off the invasion sites and prevent German reinforcements from attacking the amphibious forces.

The Canadian beachhead known as Juno was a five-mile length of sand and dunes and seaside vacation homes stretching west to east from Bernières-sur-Mer through Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, and Graye-sur-Mer to Courseulles-sur-Mer. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. R.F.L. “Rod” Keller, was made responsible not only for capturing Juno, but also for striking inland (southward) from there once the coastal defenses had been overcome.

To allow for orderly and synchronized landings, Juno Beach was divided into two primary assault sectors that were then further divided into subsectors. From west to east, the sectors were Mike (divided into Green and Red subsectors) and Nan (divided into Green, White, and Red subsectors). Mike-Green was the farthest western and Nan-Red the farthest eastern of the Juno Beach subsectors.

Three Lines, Three Objectives

The Canadian 3rd Division’s 9th Infantry Brigade (the Highland Brigade, under Brigadier D.G. “Ben” Cunningham) was assigned to the First Canadian Army for Operation Overlord. The 9th Brigade had been designated a “reserve brigade,” but on D-Day it was an assault brigade because it was on the eastern flank of the Canadian push southward into Normandy. The 9th Brigade’s task was to land after the 7th and 8th Brigades had secured Juno Beach, move past the 8th Brigade assault troops, and then fight its way inland.

The Canadian 3rd Division’s General Staff had defined three D-Day lines: Yew, Elm, and Oak, which respectively marked three objectives in their D-Day invasion plan. The North Nova’s and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers’ objectives as laid out for Objective Oak were clear. Quoting the Sherbrooke Fusiliers’ regimental log: “To spearhead the advance south to the west of Caen and assist the 7th Brigade in Operation Oak to secure the capture of Carpiquet and its airfield, then to meet the anticipated counterattack.”

What was critical and not included in this mission statement was that the 9th Brigade was also to make contact with units from both the British 3rd Division, operating east of the Canadian 9th Brigade, and the Canadian 7th Brigade, operating west of the 9th Brigade. The three units were to form a powerful spearhead and continue to push inland. However, for this spearhead to succeed, it was crucial that the British take Caen, something they were ordered to do on D-day, but failed to accomplish.

What was omitted from the Oak mission statement were many of the operation’s details. It is said that “the devil is in the details,” and this was certainly true of Operation Oak. To reach Carpiquet, the Canadians would have to fight their way through the German-occupied villages of Villons-les-Buissons, Buron, Authie, and Franqueville; while they were doing this, their left (east) flank would be wide open to attacks by marauding units of the 21st Panzer Division, which, at that moment, was the only German armored unit in the area.

Landing the 9th Brigade

As the 7th and 8th Brigades waded ashore and struggled to capture Juno Beach, the commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, General Keller, on board the converted merchant ship (which was now a D-Day command ship, the “cruiser” HMS Hillary), struggled to make sense out of the conflicting reports he was receiving. He was forced into making a crucial decision: Where would he order the 9th Brigade to land? The preferred plan was to have the 9th Brigade land at both Bernières-sur-Mer and St. Aubin-sur-Mer; an alternate plan was to land the brigade at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

Initially, Keller was unaware that the Navy had closed the beach at St. Aubin-sur-Mer because of intense German gunfire. When he learned this, he reluctantly ordered the entire brigade to land at Bernières-sur-Mer, a narrow “Nan-White” beach whose exits were already packed with 8th Brigade men and equipment––the equipment ranging from light bicycles to trucks and tanks. The bicycles were initially brought ashore to be used to speed up the infantry advance on country roads but were quickly cast aside because they were easy targets for German snipers.

Cunningham’s brigade had waited tensely, as the North Nova Scotia Highlanders War Diary, 3-6 June, 1944, recorded: “At 0630 hours all wireless sets were on listening watch to keep the Battalion informed of the progress of the assault battalions. At 11:00 am the orders came through that we were to land.” (0630 was really 0430, as England was using Double Daylight Saving Time, the clock being set back two hours.)

Once landed, Cunningham had orders to push through the 8th Brigade units as soon as the 8th had captured Beny-sur-Mer, code-named “Elder,” which would be the brigade’s assembly area. Beny-sur-Mer’s time of capture is uncertain but it was taken sometime around noon by C Company of Le Régiment de la Chaudière, a unit from the French-Canadian Province of Quebec that had been assigned to the 8th Brigade.

The 9th Brigade reached the shore with the second assault wave; the 9th’s first regiment to land was the North Novas. Though reported times vary and often conflict, it appears that the North Novas began coming ashore near Bernières-sur-Mer at 11:40 am––a time when the narrow invasion beach was already very heavily congested with 8th Brigade troops and equipment. At 12:05 pm, 9th Brigade Headquarters erroneously reported, “Beaches crowded, standing off waiting to land.” However, 15 minutes later, at 12:20 pm, headquarters signaled that the 9th Brigade had landed and its units were ready to move inland toward the assembly area at Elder.

Advancing in “Tommy Cookers”

No matter what headquarters reported, it appears that the North Novas and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers were not completely ashore until 2:00 pm and, because of congestion at the beach exits, did not begin moving toward Beny-sur-Mer until 4:05 pm. They were followed by the brigade’s two other regiments, the Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders, and the Highland Light Infantry of Canada. At 6:20 pm, the North Novas and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers, acting together as the 9th’s advance attack force, left the Beny-sur-Mer assembly area to continue their push inland. The Stormont and Highland Regiments remained in the assembly area.

The lead North Nova-Sherbrooke Fusilier unit was the Reconnaissance Troop of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment, traveling in Stuart light tanks (a tank built by the Cadillac Division of General Motors and powered by a Cadillac V8 engine). They were followed by the North Nova’s C Company, mounted on the carriers of the regiment’s Carrier Platoon, which was followed by the Machine Gun Platoon from C Company of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa. (On D-Day, the Cameron Highlanders’ 1st Battalion landed on the beaches of Normandy, the only Ottawa unit to do so. The Camerons functioned as a divisional reserve and served much of the following months spread out at company and platoon levels, providing machine-gun and mortar support for the 3rd Canadian Division’s infantry battalions.)

The Cameron Highlanders were followed by a troop of M10 tank destroyers from the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, these weapons being built on the chassis of the American M4 Sherman tank. Next came the balance of the North Novas’ Support Company, followed by an advance guard riding on the tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers. In total, this was a mixed force of some 300 men.

However, riding on a Sherman tank was especially dangerous. Three-quarters of the 27th Armoured Regiment’s battle tanks were M4 Sherman Mk III 30-ton medium tanks. The Sherman was completely outgunned and inadequately armored compared to the heavier German Panther and Tiger tanks. Particularly lethal was the German 88mm anti-tank gun, originally an anti-aircraft gun that had been modified and then used as a field piece to successfully decimate Allied tank and infantry units in Egypt, Libya, and Russia. In any confined area, the casualties that an 88 could cause were horrific. Trooper L.J. Gilbert, a tank soldier with the Sherbrooke Fusiliers, summed it up in few words: “Their eighty-eights were really terrible. We had nothing like them.”

If the 88s were not lethal enough, the Shermans were built with an unfortunately high profile that furnished a prominent target, which made detecting the tank a simple matter. When a Sherman was hit, it readily exploded in flames because it was propelled by gasoline rather than diesel fuel.

Gilbert, again quoting the Sherbrooke logs: “We soon got to find out what the Germans called our tanks—‘Tommy cookers.’” Gilbert did not report what the British Tommy tank soldiers thought of the Sherman, but in the same, dark vein, the Americans named their Sherman tanks “Purple Heart boxes” and, with similar bleak humor, they called them “Ronsons” (after a popular cigarette lighter that, according to the advertising slogan, “lights first time, every time”).

14,000 Canadians Landed on D-Day

Nevertheless, the North Novas and the Fusiliers, with their dangerous tanks, continued to push southward against German mortar and machine-gun fire. They fought their way to Villons-les-Buissons and were now about four miles from Carpiquet. With British Double Daylight Savings Time, they would have had plenty of daylight left to take Carpiquet. However, the brigade was ordered to halt by Lt. Gen. Miles C. Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army, under whom the 3rd Canadian Division served.

Dempsey’s decision was based on events around Caen. Shortly after 4:00 pm, a scout troop of the British Staffordshire Yeomanry reported that a 21st Panzer battle group consisting of 50 tanks and a battalion of infantry, advancing from Caen, was moving toward the gap between the Canadian Juno and British Sword Beaches. Dempsey acted in haste and ordered all three of his assault divisions—the divisions from Sword, Juno, and Gold Beaches—to dig in. Dempsey did not know that the German battle group he feared was approaching had already been ordered to withdraw. Dempsey’s “dig in” orders went out sometime after 7:00 pm, and General Keller’s headquarters confirmed the order at 9:15 pm.

To Dempsey’s cautious reasoning, it was dangerous to allow the Canadians to continue advancing south in the dark and further extend their unprotected left (east) flank in an area where German armored units were active. He felt it would be better to wait until dawn and hope that the British assault troops could overcome the resistance they were facing and take Caen, then join with the Canadians and quickly capture the Caen-Carpiquet airport. What Dempsey was hoping for did not happen because the British did not capture Caen.

After receiving Dempsey’s order to halt, General Cunningham commanded his vanguard to stop and dig in. The two regiments formed a fortress on the high ground around the crossroads between the villages of Anisy and Villons-les-Buissons. The North Novas and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers were totally alone when night fell; the brigade’s other regiments were still at their assembly area at Beny-sur-Mer. The Canadians spent an uneasy night, staring and listening in the blackness. Sherbrooke Fusilier tank commander Sergeant T.C. Reid later recalled: “What a bastard of a night, no time for sleep, no time to eat, no time for anything but looking into the dark and wondering what’s ahead.”

The Canadians were attacked and fought several skirmishes with nomadic groups of disorganized German stragglers. At the end of D-Day, some 14,000 Canadians had been successfully landed, and the North Nova and Fusilier Regiments of the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division had penetrated farther into France than any other Allied force. However, on the evening of D-Day, they were unaware how precarious their situation was becoming, or how unexpectedly grim it would become the next day.

The “Boy Soldiers” of the “Murder Division”

D-Day caught the German top military echelon flat-footed; Feldmarschal Erwin Rommel, commanding Army Group B, which was responsible for Normandy’s defense, was at his wife’s birthday party back in Germany. Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger, who commanded the 21st Panzer Division (which was already in the Normandy area), was apparently visiting his mistress in Paris, though later he pushed hard to deny this. Because Hitler had not believed the invasion would strike the Normandy beaches (he, like many in the German high command, fell for the Allies’ deception plan and was convinced the attack would come at the Pas de Calais), there was only one panzer division near the the coast—Feuchtinger’s.

At about 9:30 am, Rommel was notified of the landings, whereas Hitler was informed when he awoke, sometime around noon (senior officers were said to be afraid to wake him). After Hitler awoke, it is believed that it was not until about 4 pm that he released three reserve panzer divisions: the 12th SS Panzer, the Panzer Lehr, and the 21st Panzer.

One of the units that moved northward toward Caen was the 12th SS Panzer Division’s Panzergrenadier Regiment 25. It arrived in the Caen sector about midnight of D-Day. The 25th was a regiment of Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) soldiers, and the North Novas and the Sherbrookes would soon be facing “child soldiers” between 16 and 18 years of age in a division that some called the “Baby Division,” while others called it the “Murder Division.”

No matter what the division’s name, the “boy soldiers” were dedicated, ruthless, and highly trained fighters. Their officers and noncommissioned officers were recruited from the elite 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, Hitler’s personal bodyguard regiment. The vast majority of rank-and-file soldiers and panzergrenadiers (motorized or mechanized infantry) in the division were intelligent boys who had been indoctrinated from a very young age with the brutal tenets of Nazism’s perverted theologies. The young troops became the living embodiment of Hitler’s concept of ideologically and racially pure Aryan warriors.

The commander of SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment 25 was the fanatical 33-year-old SS-Standartenführer (Colonel) Kurt “Panzer” Meyer. Tall and rigidly arrogant, Meyer was the epitome of the Nazi Aryan. He had shown no qualms about commanding his young soldiers to kill civilians, nor had he displayed any remorse whatsoever about ordering them to commit suicide rather than allowing themselves to be captured. He said: “Remember, the last round in your magazine is for yourself.”

A Counterattack For D+1

The Hitler Youth, much to the frustration of its officers, had been ordered by Hitler to remain on standby duty south of Lisieux, 28 miles east of Caen, and not to move until Hitler gave the command personally. After Hitler’s orders finally came through late on the afternoon of D-Day (reported times vary), it had taken Meyer and his regiment about eight hours to reach the Caen area; a significant amount of the regiment’s travel time was spent hiding in roadside ditches trying to survive powerful Allied air attacks.

The German 716th Infantry Division, commanded by Generallieutenant Wilhelm Richter, was responsible for defending both the Canadian and British target beaches. Richter recalled a late-night D-Day meeting between Meyer, Feuchtinger (who, besides commanding the 21st Panzer Division, also acted as liaison for the elite German armored unit, the Panzer Lehr Division), and himself.

A counterattack was planned for D+1 that would have the 21st Panzer Division operating east of Caen while, west of Caen, the 12th SS Panzer Division, together with the Panzer Lehr Division, were to sweep forward into the Canadian beachhead, cut it, and then smash it into the sea. During this meeting, Meyer, perhaps recalling August 1942 when the Canadian 2nd Division was decimated on the beachhead during the abortive invasion at Dieppe, proudly announced that he would “throw those little Canadian fishes into the sea.”

Capturing Villons-les-Buissons

Even after it became obvious that Caen would not be taken on D-Day, Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, who commanded the British and Canadian ground units, did not modify his orders. General Keller commanded the North Novas and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers to continue fighting their way inland. The orders were passed down the chain of command and, at 6:45 am on D+1, Ben Cunningham sent word that the advance was to continue as soon as the men were ready. The two regiments moved out in the same order they had used during the previous day and now advanced toward Villons-les-Buissons, a town northwest of both Buron and Authie.

Initially, the Canadians faced little opposition—only sporadic sniper and mortar fire. They moved across a gently rolling plain marked by occasional clusters of trees, farm hedges, and haystacks. They passed through tiny villages where farmers lived and worked among clumps of small houses, barns, and outbuildings, their cluster of farms surrounding a village center comprising a church, a few small shops, and an occasional tiny café. Stretches of stone wall were a part of each community, as was a horse pond. Had a war not been going on, it would have been a quiet, picturesque scene.

Villons-les-Buissons was taken at about 9:30 am during a pincer attack in which a German antitank gun and a 16-barreled mortar were destroyed. The North Novas’ Company A moved around the west side of the village, while Company B came around the village’s east side. The remainder of the regiment proceeded directly into and through the town.

Kurt Meyer’s Unseen Panzergrenadier Regiment

While Villons-les-Buissons was being taken, A Company advanced to the west of Les Buissons, a town southwest of Villons-les-Buissons. The Canadians encountered and cleared a small group of snipers and machine guns. This took time, however, so when the company was free to continue, the rest of the battalion had moved ahead of them. They were now on their own.

B Company then ran into trouble. They were riding on Shermans when they suddenly came under heavy fire from St. Contest, a village west of Buron. As the shelling was obviously to defend Buron, it became grimly certain to the Canadians that if St. Contest was still in German hands, then so was Buron, and, if Buron was still under German control, it was assured that nearby Authie and Caen were also still held by the enemy. It also seemed obvious to the Canadians that the British 3rd Division, on their left flank, had been unable to keep parallel with them, according to plan. The North Novas and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers found that they were alone and unprotected on either flank.

The Canadian 7th Brigade was keeping parallel with the 9th Brigade but was too far to the right (west)—so much so that none of its units was visible to the North Novas or the Sherbrookes. It was, therefore, very doubtful if the 7th could be of any help if the situation became worse, which it soon did.

Unaware that the odds were rapidly turning against them, the Canadians did not hesitate as the reserve squadron received orders to send one troop after another forward to Buron to assist the vanguard. The Sherbrooke Fusiliers moved quickly and silenced both the German mortar and machine-gun fire, and Buron soon fell.

The Canadian push toward Carpiquet was planned on the assumption that they would be facing only units of the 21st Panzer and the 716th Infantry Divisions. Allied air reconnaissance did not report that an entire panzergrenadier regiment, complete with a battalion of Pzkpfw IV Ausf (commonly known as the Panzer IV) medium tanks, each mounting a 75mm main gun, was arriving at St. Germain and was assembling on the back slope south of the Caen-Bayeux road.

St. Germain was a short distance from the Abbaye d’Ardenne and the Canadians soon painfully learned that the towers of the Abbaye had become Kurt Meyer’s headquarters. The Canadians did not yet know about Kurt Meyer. If the North Novas and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers didn’t know about Meyer, he didn’t know about them yet, either, but the two regiments would soon be under the powerful and totally unexpected and unprepared-for attacks by Meyer’s SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 25.

“It Was a Breeze”

Meyer’s elite Hitler Youth faced the two volunteer Canadian regiments, the North Novas being mainly farmers and fishermen in civilian life, and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers, who were mostly volunteer mill and factory workers. Whereas Meyer’s “baby soldiers” were commanded by experienced and brutal officers, most of whom had learned their craft in vicious battles in Russia, the men of the Canadian 3rd Division were rightly called “amateur soldiers.” Although many of the division’s generals were graduates of Canada’s Royal Military College, most of the other officers, from colonel on down through lieutenant (except for the very few who had served in World War I), were simply “citizen soldiers” without any combat experience. Many of these “amateurs” had trained for as long as five years, repeating countless drills without ever seeing any blood. That changed on D-Day; it would change much more on D+1. This upcoming battle would be the first battle for both groups.

Meyer set up his headquarters in the Abbaye d’Ardenne, just over a mile from Authie. The Abbaye consisted of an imposing group of medieval buildings that included an early Gothic church, a chateau, and several farm buildings, encircled by stone walls and surrounded by fields of grain. Meyer made the church tower his command post because the Abbaye was on high ground, and this, coupled with the height of the tower, gave him an unrestricted view of the area.

At about 1 pm, the Canadians spotted German armor about a half mile east of Authie and a tank battle began. Sergeant T.C. Reid, writing in his log, reported: “I discovered two [German tanks] at about a distance of 800 or 900 yards. [I was instructed] to take the one on the left and my gunner, Trooper L.J. Gilbert … with his first, his second and third shots burnt said tank up. In the mean time, Sergeant Cathcart, who had come up and joined us, or Lt. MacLean, I couldn’t truthfully say, blew the other [tank] up.”

Reid then went on to log the Sherbrooke Fusilier victory in the battle for Authie: “[Our tanks] were running line abreast. The first house we came to gave forth machine-gun fire so I lobbed high explosives (H.E.) in the windows. Those [Germans] that ran out on the road were smacked down by our machine gun fire. We shoved on again and it was a breeze….”

Authie had been taken. What happened after that was not a breeze.

The Canadian’s Unprotected Flank

Meyer’s corps headquarters had ordered the 12th SS and 21st Panzer units to begin their combined attack against the Canadian beaches at 4 pm, but the unexpected arrival of the North Novas and the Sherbrookes removed all possibility of surprise, and had also raised the chance of his regiment being outflanked. Meyer could not wait until 4 pm and then attack the beaches. Even though his forces were not completely ready, he would hit the “Canadian fishes” at once.

A surprised Meyer had watched the Canadian approach from the Abbaye d’Ardenne tower and had seen the Canadians pass directly in front of his 2nd Battalion panzers. He later wrote in his autobiography, Grenadiers: “Was I seeing clearly? An enemy tank was pushing … [Going forward] then stopped…. The commander opened his hatch and observed the terrain. Was he blind? Didn’t he realize he was only 200 meters from [our Second Battalion panzers]? The enemy was showing us its unprotected flank…. I then saw what was happening.… The tank had been sent forward to provide flank cover. The enemy tanks were rolling towards Authie from Buron. My God! What an opportunity. The tanks were moving right across [our front]…. The enemy formation was showing us its unprotected flank….”

Meyer readied two of his three infantry battalions and, also, three Panzer IV companies, with about 50 Panzer IV tanks between them. At about this time, Major Don Learment, who was commanding the Canadian spearhead, felt he could hold Authie and began to organize its defenses. Able Company, advancing on the west, was ordered to dig in on the high ground behind Authie while the rest of the battalion would hold at Buron. Although this was a textbook response to the expectation of an enemy counterattack, it required naval and artillery support to succeed, something the Canadians did not have.

Fighting Without Support

The naval problem was straightforward. A young Royal Navy officer bearing the title Forward Observer, Bombardment, and attached to the 9th Brigade, broke into tears when he lost radio contact with his ship, the light cruiser HMS Belfast, a cruiser that was “light” in name but not in clout. Belfast’s main armament was the BL Maxis 6-inch gun, which could send a shell to a maximum distance of 14 . Using guns with this range, the Belfast, with its four triple-gun turrets, could typically fire at a maximum rate of eight rounds per gun, per minute. Luckily for some Canadians, the young officer’s radio was later repaired with radio parts taken from damaged tanks. For other Canadians, the repair came too late. (Today the Belfast is a floating museum, moored on the River Thames between the London and Tower Bridges.)

The ground delay involved the 14th Field Regiment which, like the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa, was a divisional support unit designed to be sent where needed. The regiment consisted of the 34th, 66th, and 81st Field Batteries, each battery consisting of four field “Priest” 105mm self-propelled guns, these guns derived from American experiences with howitzers mounted on half-tracks. (The weapon was nicknamed “Priest”by its British crews because of its pulpit-shaped machine-gun turret.)

Unfortunately, when two of the 14th’s batteries reached Basly, they came under fire and were held up by mortars coming from Douvres-la-Déliverande, a town southwest of Luc-sur-Mer. Because of this holdup, the 14th could not provide artillery support to the North Novas or the Sherbrookes for two hours. The two regiments were thus without either sea and ground support when Kurt Meyer launched his attack.

When Meyer struck, he struck hard. A Squadron of Sherbrooke tanks was attacked by German armor, and the two forward troops on Authie’s west side were forced to retreat after losing three of their six tanks. Similarly, B Squadron, to the east of the village, fought a close-range battle before heavy artillery fire and losses forced it to withdraw. Sergeant Stan Duke of the North Nova Scotians recalled: “Within minutes most of our tanks had been knocked out; everything happened so fast we never had a chance. The Shermans went up like torches, explosions first, fire, smoke and screaming men.”

With their armor support gone, about 100 North Novas were suddenly cut off and left alone trying to defend both themselves and their Authie position. The only tank they could call upon was a single Firefly, the British variant of the American Sherman, but fitted with a British 17-pounder (76.2mm, 4-inch) antitank gun as its main weapon.

Able Company, on the high ground north of Authie, was still digging in when the Germans attacked, but without armored or artillery support; they were quickly surrounded and taken prisoner. The battle for Authie itself began with a heavy barrage fired by 12th SS artillery; this was followed by a tank-infantry attack. The Canadians held out for more than an hour, beating back several German charges and inflicting more than 100 German casualties but, outnumbered and without support, the Canadians were forced to surrender.

Atrocities of the Hitler Youth

Surrendering to the Hitler Youth became a death warrant for many Canadian prisoners of war. It started when the Hitler Youth began murdering Canadian prisoners in the streets of Authie but did not end there. Canadian POWs were also killed at the Abbaye d’Ardenne, Buron, and elsewhere. In Authie, at the southern end of the village, the Canadian POWs were first disarmed and then told to remove their helmets. They were then shot at close range and, after this, the Hitler Youth soldiers obscenely mutilated the bodies of the prisoners they had just murdered.

In one incident, German soldiers propped up the body of a murdered Canadian soldier, shoved an old hat onto his head, and then stuffed a cigarette box into his mouth. In another incident, eight lifeless Canadian bodies were dragged onto the street and repeatedly run over by passing Hitler Youth tanks, trucks, and armored vehicles. Horrified French onlookers later testified that the SS troops “whooped like drunken pirates” at what they were doing. (A street corner in southern Authie was named Place des 37 Canadiens in honor of the 37 Canadian prisoners murdered there.)

The murders at the nearby Abbaye d’Ardenne were equally brutal. After the Abbaye had quickly filled with Canadian POWs, 10 were randomly chosen and moved to the chateau next to the abbey; an 11th POW was brought there later. That evening all 11 men—five North Nova and six Sherbrooke POWs—were taken from the garden and shot to death. Ten bodies were found later, six with crushed heads.

On D+2, seven more North Novas were murdered, taken to the Abbaye and then sent one by one to their deaths. They shook hands with their comrades and were escorted by the SS to the Abbaye gardens, where they were each shot in the back of the head.

That night another heinous atrocity against Canadian POWs took place on a moonlit back road, the Caen-Fountenay road, in the Normandy countryside. Forty Canadian POWs were taken to a grassy area next to a grain field northeast of the village of Fontenay-le-Pesnel, about 10 miles west of Caen. Once in the field, they were ordered to sit down, facing east. They were clustered together in several rows, with the stretcher cases placed in the middle. As their SS murderers closed in around them, even the most hopeful of the Canadians now realized they were doomed. Any lingering hopes were shattered when Lieutenant Reginald Barker of the 3rd Canadian Antitank Regiment, who was in the first row of the bunched-together prisoners, and would certainly be hit by the bullets from the first German volley, calmly advised, “Whoever is left after the first round, go to the left.”

The Germans Delayed at Buron and Authie

The battle for Buron lasted longer and the Germans suffered heavier casualties. Buron was lost and then recaptured by the Canadians when contact was established with the HMS Belfast, which then began naval support. In addition, the 14th Field Regiment was able to move into a position from which it was able to bring its artillery into action. In spite of being able to hold Buron, the town was later abandoned when Brigade Commander Cunningham decided to move what was left of his battle group to his “Brigade Fortress” in Villons-les-Buissons, a town just five miles north of Caen, in an area that was given the name “Hell’s Corners.” The Canadians lost 110 killed, 192 wounded, and 120 taken prisoner.

The 9th Brigade was pulled back from Carpiquet and the Caen-Carpiquet airport at the moment when they were close to capturing them. A furious series of battles had taken place on D+1, battles some military historians claim the Canadians lost because of their inexperience. The Canadians were certainly inexperienced, and though these battles might be regarded as a Canadian defeat, it is also possible that a menace to the entire Allied bridgehead might have developed if the outnumbered and outgunned “Canadian fishes” hadn’t held their own against superior odds.

The “inexperienced, amateur Canadians” had destroyed 15 German tanks and killed more than 300 Hitler Youth soldiers. These German casualties, together with Meyer’s decision to quickly mount a piecemeal full-scale attack with his three battalions, effectively tied up these battalions and thus reduced the chances of further immediate large-scale German offensive action in the Normandy beachhead area.

The Controversial Sentencing of Kurt Meyers

The D+1 battles for Buron and Authie were over, but the battle for Caen was just beginning. Taking Caen proved to be a bloody and costly fight that finally ended with the town’s capture on July 20, 1944—44 days after D-Day. Montgomery’s tactics were questioned and criticized during the entire campaign. Eisenhower fumed that “it had taken 7,000 bombs to gain seven miles.”

Kurt Meyer was captured on September 6, 1944. The SS commander who wanted his Hitler Youth soldiers to commit suicide rather than surrender was found hiding in a Belgian chicken coop by partisans. The partisans gave Meyer to the Americans, who then handed him over to the Canadians. Aside from deciding suicide was better for his Hitler Youth soldiers than for himself, Meyer never changed his rabid, pro-Hitler attitude, saying to an American interrogator: “You will hear a lot against Adolf Hitler in this camp, but you will never hear it from me. As far as I am concerned, Adolf Hitler was and still is the greatest thing that happened to Germany.”

Meyer was put on trial in December 1945 in what had once been a naval barracks in Aurich, Germany. The trial came under the Convening Authority of Maj. Gen. Chris Vokes, who commanded the 3rd Canadian Division of the Canadian Occupation Force. Meyer was found guilty and sentenced to death by firing squad, but the sentence of death was soon commuted to life imprisonment by Vokes.

This lenient treatment caused a firestorm in Canada, and even as late as 1981 Vokes was apparently trying to defend his questionable action: “We … discussed the question of responsibility of a commander for the action of men under his command…. For instance, if one of his soldiers committed murder, was Meyer guilty of murder [?] But there was a vicarious responsibility….”

The verdict was debated hotly, but it didn’t matter. Meyer, first incarcerated in a Canadian prison, was soon sent back to Germany and there released from prison in 1954. He became a beer salesman and, ever the loyal SS officer, was active in HIAG, a mutual help association of Waffen-SS veterans. He died in 1961. After Meyer’s trial, there were no further Canadian trials for the murder of POWs.

The best thing would have been to leave him in prison for the remainder of his life.Death seems like the best option at the time but putting a man in a solitary jail cell, with very limited options, would,seem to me,be a more damaging sentence.Sitting day after day staring at a wall with nothing to do would drive anyone “nuts”.Even today,2021,Canadian courts are to lenient in my opinion..!!!