By Patrick J. Chaisson

The Bug was in deep trouble. On a top-secret flight over occupied Norway, this ancient, war-weary C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft became the helpless target of German antiaircraft guns, all firing desperately to bring down the transport and its precious cargo. Her pilot maneuvered violently to dodge the curtain of flak, praying his decrepit airplane would hold together long enough to make an escape. It did.

Hours later, The Bug landed safely in Scotland, where Allied intelligence officers anxiously waited. Inside were the remains of a Nazi A-4 rocket, which had recently exploded over Sweden, the first real evidence of Germany’s ballistic missile program that would shortly result in deadly V2 attacks across England.

The flight of The Bug, which took place on July 30, 1944, was one of hundreds conducted by a fleet of unmarked American military aircraft operating in and out of a supposedly neutral nation underneath the noses of the German Gestapo. The story of this secret airline is one of World War II’s most amazing classified missions and sheds new light on the role of Sweden in the fight against Nazi Germany.

Swedish Sympathy For the Allied Cause

At the start of World War II, Sweden found itself in a precarious position. When Germany conquered its Scandinavian neighbors in 1940, the Swedes were able to remain carefully neutral. Sweden possessed many cultural and economic ties to the Third Reich, regularly trading Swedish timber and machine parts in exchange for German coal.

For a time, pro-Nazi elements in the Swedish government even permitted Wehrmacht troop trains to pass through Sweden on their way to and from Norway. This was a gross violation of Swedish neutrality but may have helped keep that country free from invasion by German forces.

As the fortunes of war began shifting in late 1942, Sweden began reconsidering its relationship with Hitler’s Reich. Allied diplomats, formerly shunned, were now warmly received in Stockholm. And Sweden became a haven for those seeking to escape Germany’s grasp on Scandinavia. Over 7,800 Danish Jews fled to safety in neutral Sweden after Adolf Hitler ordered their liquidation in 1943. Sweden also accepted over 70,000 Norwegian refugees, many of whom were of military age and determined to rid their homeland of the hated German occupiers.

The Norwegian government in exile, based in London, wanted those evacuees organized and trained as resistance fighters. Norwegian diplomats met with their Swedish counterparts in early 1943 to request Sweden’s assistance in creating a force of “police troops.” This quasi-military organization would consist of 13,000 Norwegian expatriates then living along the Swedish frontier. They also wanted Sweden to allow thousands of young Norwegian refugees to depart for military training in Great Britain. Lastly, Norwegian officials asked the Swedes to aid by whatever means possible the nascent resistance movement then forming in German-occupied Norway.

Support for the Allies’ cause was indeed growing throughout Sweden, but how could its leaders respond to the Norwegian pleas while maintaining at least an illusion of neutrality?

1,400 American Airmen in Sweden

Compounding Sweden’s difficulties was the growing number of American airmen landing their battle-damaged B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator bombers inside its territory. International law required Sweden to intern the men and equipment of belligerent nations ending up there. During the first years of the war only a few British and German pilots found themselves guests of the Swedish government and were usually repatriated within a short time on a one-for-one basis.

Starting in July 1943, however, U.S. bomber crews began seeking Swedish sanctuary rather than risk bailing out over occupied Europe. As the American bombing campaign intensified in 1944, so did the number of flak-riddled aircraft heading for Sweden. Some 131 Fortresses and Liberators eventually arrived there between 1943 and 1945.

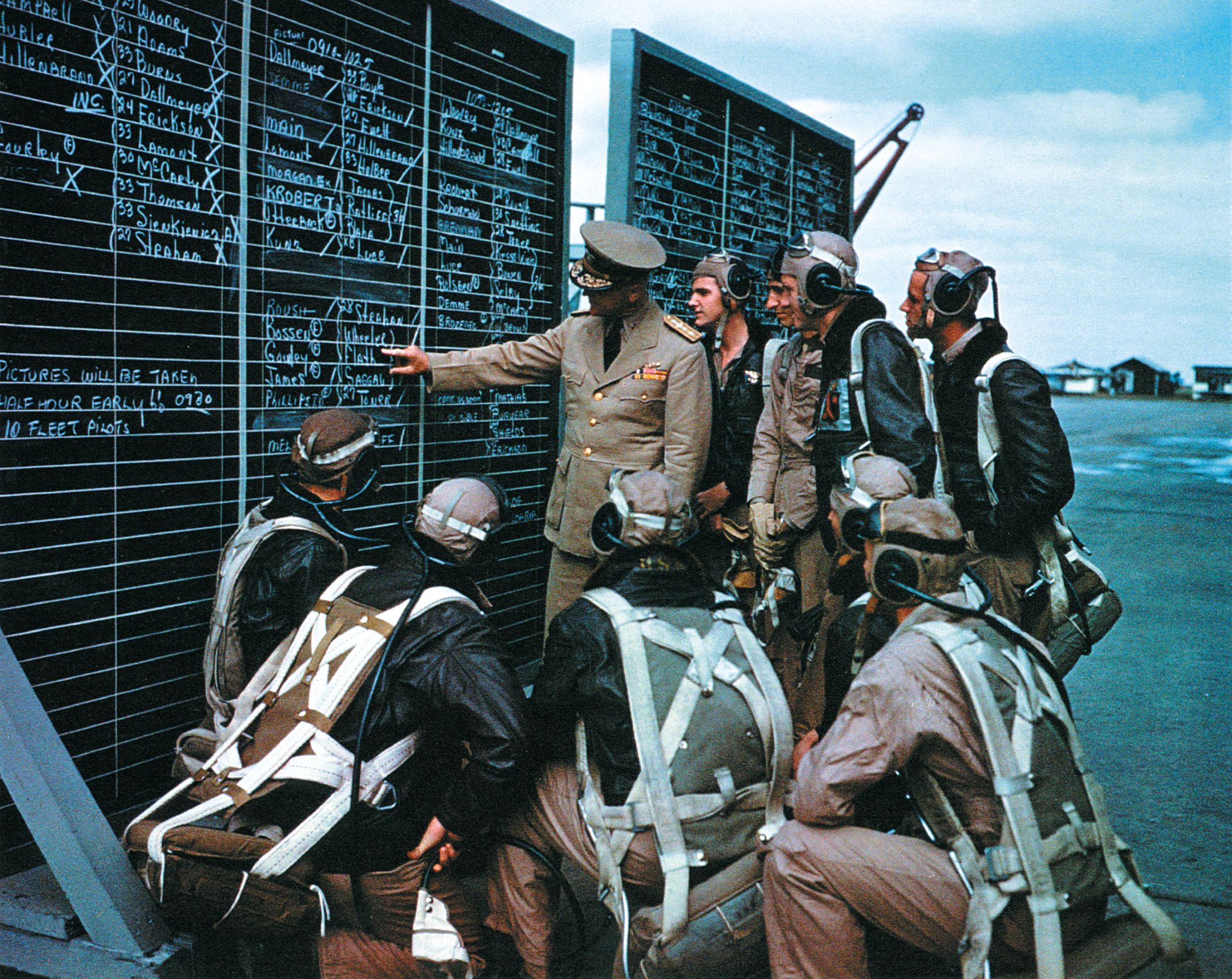

At one point, over 1,400 American flyers were interned in resort camps, hotels, and private residences across Sweden. They were certainly better off than those aviators stuck in Luftwaffe prison camps, but General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, commanding general of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, wanted these well-trained airmen back in the fight. Spaatz asked General Henry “Hap” Arnold, who commanded the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), if a diplomatic solution could be arranged for the return of U.S. flight crews from Sweden.

Arnold approached Brig. Gen. William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the World War I combat hero then running Washington’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Donovan promised his full cooperation, and soon the OSS field office in Stockholm began work to open talks with Sweden for the release of American servicemen interned there.

These negotiations succeeded; Sweden agreed to repatriate all the U.S. flyers it was currently holding, provided the Allies came and got them. There were other conditions. No military aircraft or crews could be used, and only three flights per each 24-hour period were allowed. Sweden also granted permission for Norwegian refugees to leave for military training in the United Kingdom so long as civilian airliners transported them out of the country.

The OSS Air Courier Service

Curiously, commercial air service between Great Britain and Sweden continued to operate despite the war. The British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) ran a regular weekly route between Stockholm and London using two twin-engined Lockheed Lodestars. These airliners could seat eight passengers and a small amount of cargo—clearly inadequate for what the Americans had in mind.

Arnold and Donovan agreed the OSS would need to set up its own air courier service with long-range bomber aircraft painted over and marked to resemble commercial aircraft. Their U.S. Army crews were to operate undercover as the fictitious American Air Transport Service, so civilian passports and clothing had to be obtained as well.

The Liberator-equipped 801st Bomb Group, nicknamed “The Carpetbaggers,” had long experience working with OSS operatives in France, and its crews knew how to keep a secret. These special operations airmen were perfect for the Swedish project, but who would lead them?

Operation Sonnie

Enter Colonel Bernt Balchen. This Norwegian-born adventurer was already a legend in the realm of polar exploration. A world-renowned arctic aviator, Balchen had flown over both poles with the likes of Richard Byrd and Roald Amundsen before becoming an American citizen and joining the Air Corps. He spoke English, Norwegian, Swedish, and German and knew almost everyone worth knowing in Scandinavia. Balchen was universally regarded as a courageous, charismatic airman.

His last assignment, just concluded, was the establishment of an air-sea rescue operation across stormy Greenland. Balchen’s uncanny ability to read the erratic arctic weather, as well as his unparalleled skill as a pilot, resulted in the safe recovery of many U.S. flight crews who had crash landed on the unforgiving Greenland icecap.

In short, Bernt Balchen was the man to command this high-risk mission. On January 27, 1944, General Spaatz gave Balchen his marching orders: operate a fleet of unarmed planes to and from a neutral nation without fighter protection, evacuate Norwegian resistance fighters and interned Allied airmen, carry secret cargo as required by the OSS, and accomplish all this without being caught by the Germans.

In his heavily accented English, Balchen responded: “Ve do it!”

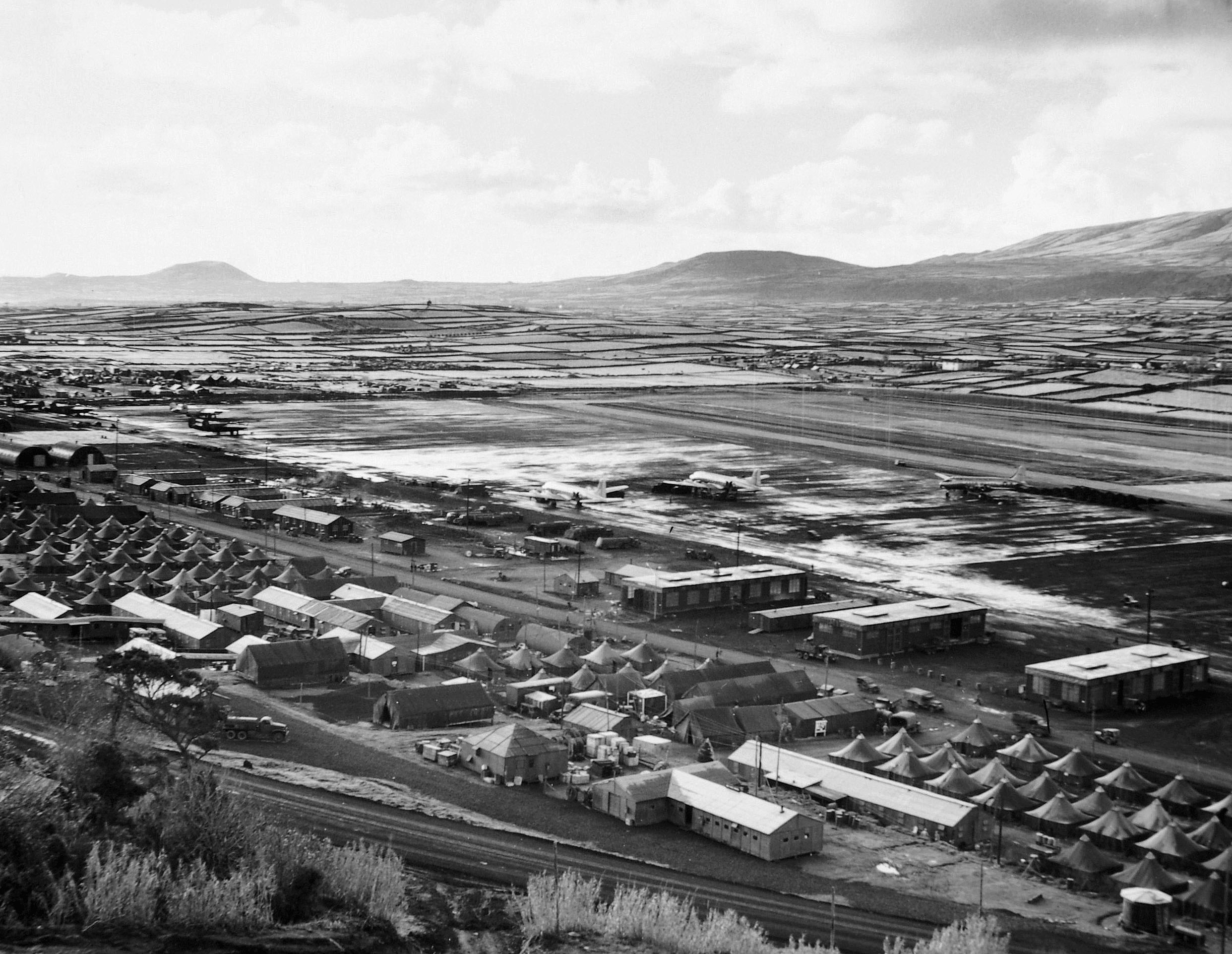

Balchen called his project Operation Sonnie in honor of the Norwegian figure skater and actress Sonja Heine, whom he greatly admired. He set up shop at the Royal Air Force base in Leuchars, Scotland, and then quietly began gathering his planes and flight crews.

BOAC Frustrates Balchen’s Efforts

First to arrive were five tired B-24D Liberators. No longer combat worthy, these aircraft were transferred to the European Division of the USAAF Air Transport Command for extensive modification. Each had its bomb bays sealed, bench seats for 35 passengers installed, all defensive armament and turrets removed, and special navigational equipment put in for the long flight to Sweden. Every B-24 was also painted in a greyish green color and marked with false British commercial registration codes. No national insignia was visible to indicate they were American airplanes.

In February, seven Carpetbagger flight crews from the 801st Bomb Group reported for duty at Leuchars. Accustomed to not asking questions, they happily accompanied Colonel Balchen to Selfridge’s department store in London to purchase business attire to wear in Sweden. The airmen also obtained U.S. passports and visas that listed their occupations as civilian airline pilots.

The Carpetbaggers were excited to work with Bert Balchen, and travel to Sweden also intrigued them. But then Balchen explained that parachutes were not to be worn as the flyers, dressed in civilian clothes, would be executed as spies if the Germans captured them.

By March 1, Balchen’s aircraft and crews were ready to begin operations. As this was a supposedly nonmilitary courier service, though, they first required flight clearance from the British Foreign Ministry. Colonel Balchen submitted the paperwork, but in one of those unfortunate mix-ups that so often plague covert operations, the United Kingdom refused permission for his planes to fly in or out of British airspace.

As mentioned previously, BOAC was already running air service between the United Kingdom and Stockholm. The airline received a fee for every Allied airman or Norwegian refugee flown out of Sweden and did not welcome the loss of revenue occasioned by this rival American Air Transport Service. Yielding to pressure from BOAC, Foreign Ministry officials denied Balchen’s clearance requests.

British commercial air policy had grounded Operation Sonnie.

Fuming over this bureaucratic snag, Colonel Balchen approached Trygve Lie, then the foreign minister of the Norwegian government in exile, with his problem. Minister Lie passed the issue on to Norway’s King Haakon at a luncheon attended by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. King Haakon whispered a few words into Mr. Churchill’s ear, and two days later Sonnie received all the necessary approvals.

Operation Sonnie Goes Off the Ground

Poor weather was forecast for occupied Norway on March 31, 1944. This suited Bernt Balchen, who would pilot the first green-painted B-24 to land at Bromma Airfield outside Stockholm that night. The 800-mile flight occurred without incident, and Balchen’s strange looking aircraft was met at the field by Swedish Air Ministry officials, national police, and OSS operatives.

After parking their Liberator in a well-guarded corner of the airport, Balchen’s crew—dressed in suits and ties and carrying civilian identification—cleared customs in time for a breakfast of steak and eggs (items almost unobtainable in wartime Britain) at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm. While the other Americans were enjoying a second helping of fresh orange juice and buttered rolls, Colonel Balchen excused himself. He had much to coordinate.

A call to the chief of the Swedish Criminological Institute secured valuable information on German espionage activities in Sweden. Balchen then visited the heads of the Swedish Air Ministry, Foreign Office, and Swedish Air Force, all of whom were prewar friends and delighted to extend their cooperation.

The aviator also met with Norwegian Underground leaders headquartered in Sweden. They provided him with accurate locations of all Luftwaffe interceptor bases and flak batteries in occupied Norway. Resistance fighters also gave Balchen classified radio codes in case his aircraft needed to communicate with their teams on the ground.

To mislead Nazi spies, Balchen’s team prepared two sets of flight plans—one that German agents in Stockholm could obtain and use to alert antiaircraft units in Norway—and another flight plan, filed secretly with the Swedish Civil Aeronautical Authority, that contained their planes’ real routes.

The return trip two days later came off without a hitch. Balchen’s plane returned to Leuchars carrying three dozen Norwegian Resistance members, the first of 3,000 recruits to receive military training in England before returning home to fight with the underground. Operation Sonnie was off to a good start.

Under the Eye of the Gestapo

Before long, 250 USAAF mechanics and support personnel arrived in Sweden masquerading as civilian technicians. Balchen rented apartment houses for them and also set up a command post at the BOAC terminal in Bromma. The Swedes assisted by moving internees and Norwegian refugees to nearby camps prior to pickup.

The presence in Stockholm of this famous polar explorer and his American compatriots could not be kept secret from the Gestapo for long. Balchen was followed everywhere he went in Sweden’s capital city, and the Sonnie crews routinely discovered that their hotel rooms had been searched while they were away.

Yet there were also advantages to the German presence in Sweden. When one of Balchen’s B-24s cracked an engine cylinder on the ground at Bromma, he jokingly approached a Swedish friend about buying one from the Germans. The helpful Swede telephoned Berlin and two days later a Lufthansa Ju-52 transport obligingly delivered the repair part—scavenged from a Liberator downed over Europe—so American mechanics could get their clandestine courier plane flying again that night.

After anxious Swedish officials complained about U.S. aircraft wearing British civil registration markings, Sonnie ground crews merely painted them over with equally bogus American codes. For example, the B-24 registered as “G-AFYO” when it landed at Bromma Airfield on April 19, 1944, departed Sweden a day later with “NC-18649” painted on its fuselage. This satisfied the Swedes, and operations continued.

Whenever weather conditions allowed, Balchen’s modified airliners made the trip to Scotland carrying up to 40 Norwegian refugees, diplomatic couriers, and returning American aircrews per flight. Captain David Schreiner, a pilot with Operation Sonnie, recalled his passengers’ discomfort: “It was anything but a luxury ride for those boys,” he said. “I just packed them in like sardines but nobody complained.”

Before long, OSS officials began asking if the Sonnie planes could deliver cargo to the Norwegian Underground then organizing in Sweden. Disguised as medical supplies, boxes of plastic explosives, detonators, and other implements of sabotage started arriving inside the converted Liberators; Swedish police looked the other way.

Operation Ball

Yet, the growing resistance movement needed more help. Learning the Royal Air Force was reluctant to fly airdrop missions over Norway during the summer months, Balchen asked OSS officers if his team could take on the job. Thus was born Operation Ball, named for the B-24 ball turret that had to be removed for these resupply drops.

Unlike Sonnie, Operation Ball was flown by armed, U.S.-marked airplanes. A second set of Liberators from the Carpetbaggers arrived at Leuchars, where they were painted in a nonreflective black scheme. Instead of the ball turret, a padded “Joe-hole” (OSS agents were all nicknamed “Joe”) was installed for delivering resistance fighters and OSS operatives.

Ball missions tested the B-24s’ long-range endurance, as well as their crews’ arctic navigational skills. A typical sortie would reach far into occupied Norway at a time of the year when there is perpetual daylight, locate the drop zone, and then deliver a payload of equipment, munitions, and OSS Joes before returning home to Scotland. These flights never entered Swedish airspace.

The first Ball mission took place on June 22, 1944. True to form, Balchen flew this one personally. His B-24 successfully dropped 20 supply canisters to resistance fighters despite the presence of nearby German flak guns. Thanks to the underground, Balchen’s aviators knew all their enemy’s recognition codes and flashed them whenever Luftwaffe searchlights threatened.

Bernt Balchen’s crews made 161 Project Ball flights from June to September 1944. The Norwegian-American colonel piloted 39 of these runs himself. One of Balchen’s gunners, A.J. Sharpe, described his commander thusly: “I still recall him as the best flyer, the best navigator, and the most deadly soldier I ever knew. Balchen had a built-in compass in his brain which worked when the regular compass went crazy. We did not fly under cover of darkness, for that far north it doesn’t get dark in July and August. We flew at fifty foot altitudes and ducked in and out of fjords. Canisters were dropped at [approximately] 100 feet and agents at 400.”

On June 13, 1944, an A-4 rocket (precursor to the deadly V2) exploded over Bäckebo in southern Sweden. After examining the fragments closely themselves, Swedish Air Ministry officials invited the Allies to take the recovered “air torpedo” (code name for the A-4) back to Great Britain. Unfortunately, the rocket was too big to fit into a Sonnie B-24.

As a cranky old Air Transportation Command C-47 made its way to Sweden, Gestapo agents scoured the countryside in search of their missing missile. German air defense units in Norway also went on high alert for any Allied transport plane that might be carrying the A-4 to England. Despite the Nazis’ best efforts, The Bug managed to sneak this intelligence gold mine out of Sweden and into the custody of British analysts.

More Missions For Colonel Balchen

The summer of 1944 brought with it news of great Allied victories, which caused Sweden’s pretense at neutrality to fade. The sight of uniformed Americans became a common one on the streets of Stockholm as Colonel Balchen entered the next phase of his secret Scandinavian assignment—the liberation of Norway. With the Swedes’ cooperation, Balchen was busier than ever.

Operation Where and When transported tons of cargo and over 1,400 resistance fighters organized as police troops from training centers in Sweden into occupied Norway. For this project Balchen used 10 USAAF-marked and -crewed C-47 transports operating out of Kallax Airfield in northern Sweden to fly these soldiers across the border to Kirkennes, Norway. Swedish fighters even escorted his transports whenever possible.

The SEPALS Project, Balchen’s other clandestine operation, employed Carpetbagger B-24s from Leuchars to drop saboteurs and supplies deep behind enemy lines. One such mission put 15 OSS Joes led by future CIA director William Colby down near Jaevsjo, Norway, on March 22, 1945. Their job was to destroy a vital rail bridge, which they managed to accomplish only after an arduous 12-day ski trek across mountainous terrain while dodging German patrols and collaborators the entire time.

At the end of hostilities, Balchen’s work still was not done. Some 70,000 starving Soviet prisoners had been abandoned by the Germans in Norway, so his C-47s provided rations and medical supplies until the Soviets could be repatriated. And Sonnie flights continued until June 1945, when the last American internees were returned from Sweden.

Balchen’s Remarkable Successes

By all measures, these air operations had achieved superb results. Operation Sonnie transported some 4,304 evacuees from Sweden to the United Kingdom over a 13-month period. Ball flew its 161 resupply sorties throughout the summer of 1944 in support of Norwegian Resistance fighters. Balchen’s SEPALS project delivered 50 OSS Joes and 11,040 pounds of sabotage equipment from December 1944 to the end of the war. The 572 missions flown during Operation Where and When moved 1,442 Norwegian ski troops, tons of provisions, and an entire field hospital under the enemy’s noses to landing fields in occupied Norway.

Balanced against these successes was a total of three aircraft lost. Though none were destroyed by enemy fire, two B-24s did crash in Scandinavia as a result of mechanical failure. A third Liberator was accidentally shot down by the Soviets after being forced to divert to Murmansk during a Ball airdrop mission. Eighteen U.S. airmen perished in these mishaps.

Colonel Bernt Balchen was at the controls of the first American aircraft to land in Norway following Germany’s surrender. He could not help but smile as Luftwaffe ground crewmen efficiently parked his C-47 transport at Bodø Airport next to a line of German Junkers Ju-88 fighter bombers and Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters. But Balchen, delivering a load of sorely needed medical supplies, could not dwell for long on such an ironic scene.

Norway, the land of his birth, was once again free. No one had done more to make this possible than Colonel Bernt Balchen and his secret air force. Accomplishing what others deemed impossible, this intrepid group of aviators flew some of World War II’s most hazardous missions over forbidding terrain—often in terrible weather and unable to defend themselves against enemy interceptors.

Today, their legacy lives on in the U.S. Air Force’s Special Operations Command (AFSOC), whose modern transport planes quietly conduct highly classified operations across Afghanistan and many other global hot spots. The AFSOC motto “Any Time Any Place” is a slogan Bert Balchen would surely have appreciated.

Impressive! An almost unbelieveable level of bravery, intelligence and patriotisme. Norway was occupied until the last day of the war by a very well equipped German force of hundreds of thousands making such operations a true challenge to the very last „moment“! Very interesting report and a real „eye opener“. Thank you.

Werner E. Wiedmer

CH-2505 Bienne, Switzerland

I am looking for information on a flight of five Sonnie aircraft that left Bromma with only one which arrived in Leuchars, the others having been shot down enroute. Are there records available of aircrews and aircraft lost during the operation?

Any participants still alive?

I knew a young Norwegian (then), Terje Jacobson, who escaped Norway with his mother and another member of the Hemesfront, on foot over the mountains via Abisko and further to Kiruna and then on to Stockholm, where he flew on the single B-24 or C-89 aircraft of the five mentioned above, joined the Norwegian Royal Air Force in Exile, and then landed with the Norwegian King back in Oslo, Norway at the end of the war when the US Army’s 99th Infantry Battalion (all Norwegian speaking) had also arrived to act as the King’s body guard and to take the surrender of the Germans. Terje went to the University of California in Berkeley after the war to study Architecture, lived in International House, and then returned to Tromsö, Norway where he designed one of the terminal buildings at Oslo’s Gardemon Airport.

I organized a symposium on the sinking of the German Battleship, Türpitz, in 2001 and Terje, Leif Arneberg, Kurt Schulz, Tony Iveson, Alfred Zuba and a British member of a three- man sub all told their stories, which we video taped.,

Fascinating history.