By Blaine Taylor

An estimated four million Red Army soldiers were captured by the Germans during the six months after the launching of Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, on June 22, 1941. Indeed, the chief of the German General Staff, Colonel General Franz Halder, wrote, “The Russians have lost this war in the first eight days! Their casualties—in both men and equipment—are unimaginable.”

He was both right and wrong as it turned out, and thus Adolf Hitler was not the only German who had underestimated the Soviets. The German field marshals and generals share in the blame for the debacle that was to come in the East. The German Armed Forces High Command, the OKW, had originally counted on a 12-week war against the staggering Soviet Union, but under Joseph Stalin, the Soviets rallied and came back stronger than ever.

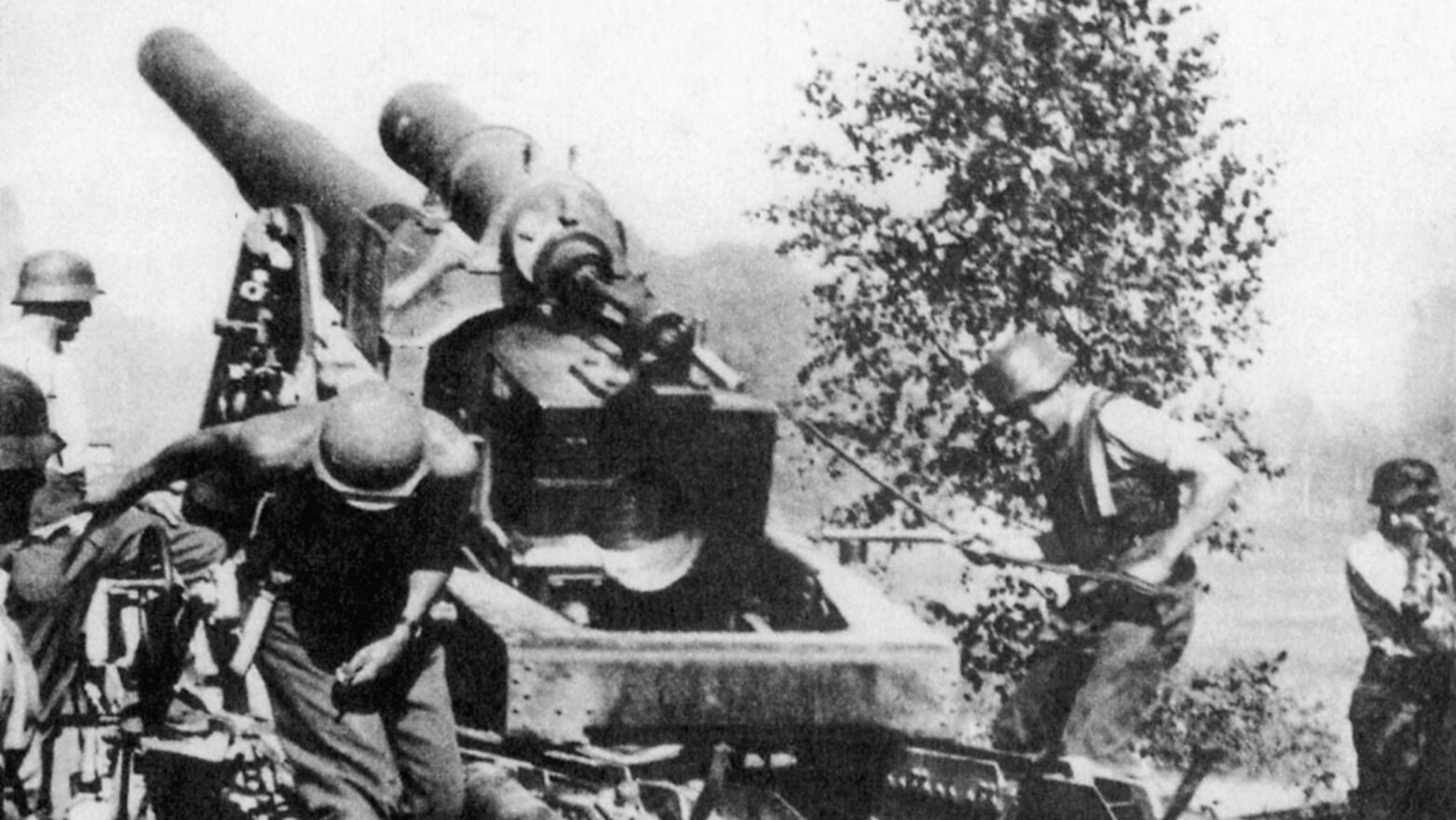

The Blitzkrieg into Russia, featuring panzer armor divisions, was initially successful but ultimately failed. The Eastern Front war dragged on for four years and was characterized by unprecedented ferocity and loss of life, not only due to the war itself, but also to starvation, disease, slave-like working conditions, and the vast ethnic cleansing occurring under both Stalin and Hitler for different reasons.

The height of the Stalinist repression, the Great Terror, occurred in the late 1930s just prior to the German invasion. Minority nationalities inside the Soviet Union, including the Cossacks, were among those cruelly victimized during this period, especially those who posed resistance. Stalin ruthlessly expanded the collectivization program into an offensive against the peasantry. Millions were displaced, and millions were killed. A significant number of Soviet citizens, including many of the Cossacks, therefore greeted the invading Germans as liberators. Thousands of ordinary Soviets became partisans in the German military.

The Cossacks: a Privileged Military Class

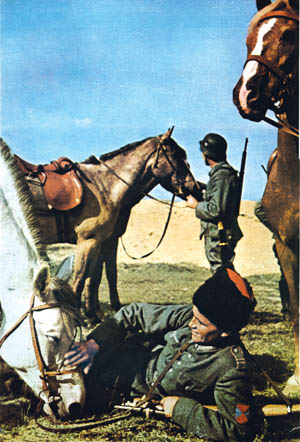

Traditionally, the Cossacks derived mostly from the area of southern Ukraine. They had lived in clans that were designated by the name of the nearest major river, i.e., Don Cossacks, Kuban Cossacks, Ural Cossacks. Their superior horsemanship, proficiency with the saber, and colorful uniforms defined them. The great majority of them were loyal to the Romanov family, going all the way back to Catherine the Great. By the time of the last tsars, the Cossacks were widely viewed as a privileged military class.

During the Bolshevik revolution, sectors of the Cossacks put up some of the toughest resistance experienced anywhere by the Red Army. Therefore, after the Revolution, the Bolsheviks retaliated by destroying all federated Cossack Republics in a terribly cruel manner, considering them all as part of “White Russia” (sympathetic to the tsar), though it wasn’t necessarily true.

Just after Russia’s poor military showing in the 1939 Russo-Finnish War, Stalin reintroduced the Cossacks into the Soviet military. Yet just 60 days after the beginning of World War II, the first major defection of Red Army soldiers to the German side occurred: It was a Cossack unit, the 436th Infantry, commanded by Major Ivan Nikitich Kononov. On August 3, 1941, fully 70,000 Cossacks went over to fight for the Germans. Another 50,000 joined them by October 1942. By that time, the German Army had established a semi-autonomous Cossack District from which they could recruit.

It should be emphasized that their defection to the German side was not done in favor of Nazism, but for the love of their homeland and for the cause of a second Russian Civil War. There was tremendous risk in going against the Red Army, however. Hitler declared that Russian soldiers would not be granted POW status, which meant captives would be treated as subhuman. Of the nearly six million Russians taken prisoner after 1941, only 1.1 million lived to see the end of the war. Given the brutality of the Germans, it seems incomprehensible that so many of these people were still willing to don German uniforms. Such was their hatred of Stalin.

By February of 1945, when it was evident the Germans had all but lost the war, the Cossacks, under the leadership of German Maj. Gen. Helmuth von Pannwitz, wanted to surrender to the British Army in liberated Austria, to escape being returned to Stalinist tyranny. Negotiations were opened on this basis in good faith.

Fates Decided at Yalta

The fate of these Cossacks had already been decided, however, at Yalta in February, when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, American President Franklin Roosevelt, and Russian Marshal Josef Stalin met to decide the final issues remaining from the war in Europe. One issue on the table was called “reciprocal repatriation.” This discussion related to Allied prisoners in Germany liberated by Soviet forces and also to the prisoners of Soviet origin serving in the German Army, among whom the dissident Cossacks formed a major component. A trilateral commission was established to form an agreement acceptable to all three nations on issues including the displaced civilian populations.

Two basically identical agreements were signed on February 11, 1945, by the British and Americans. The British agreement stipulated that all Soviet citizens “liberated by the Allied armies—as soon as possible after their liberation—were to be separated from German prisoners of war and lodged in separate camps…” and “situated in camps or other localities to which the Soviet authorities responsible for their repatriation would have immediate access….

“…The British authorities responsible would cooperate with their Soviet colleagues in the United Kingdom with a view to identifying all Soviet citizens who had been liberated and transferred to the UK.” The British would also “be responsible for the transport of Soviet citizens up unto the moment that said citizens would be handed over to Soviet authorities.”

As pointed out by noted authority Francois de Lannoy, “If there was nothing in the agreement that stated specifically the necessity of repatriating all Soviet citizens regardless of their wishes and—if necessary, by the use of force— it was well understood that from a legal point of view, that was what was intended.”

This, then, was the very crux of the thorny matter that would shatter the Cossack nation, bedevil the British civilian and military authorities in occupied Austria, and poison relations between the still anti-Red East and the West for decades afterward.

Concluded de Lannoy, “According to Stalin’s wishes, the contents of the agreements were kept secret, and did not figure in the final communiqué issued at the end of the Yalta Conference. It is evident, though, that had the details been published openly, those Soviet citizens serving the Wehrmacht who would’ve been well aware of their fate if returned to the Soviet Union (death, concentration camp, or deportation) would’ve taken all necessary steps to avoid falling into the hands of the Allies.”

“On Oct. 1, 1945, Gen. (later Marshal) Filip Ivanovich Golikov, responsible for repatriation of Soviet citizens after the war, announced that of 5,236,130 Soviets repatriated, 1,645,633 had found employment and 750,000 were waiting for a job. Of the remaining 2,840,367 of whom no further details were given, it is probable that they died in transit, were executed, or sent to concentration camps.

“At the time of the Yalta Conference, 100,000 Soviet soldiers serving the Wehrmacht had been captured by the Allied forces.…The Soviets … had liberated 50,000 British POWs who had sought refuge in the Soviet Union, as well as far greater numbers of French soldiers…,” most of whom had been captured by the Germans in 1940.

Cossacks in the Nazi Ranks

From the summer of 1941 through 1943, none of the top German political leaders involved with the Eastern Front wanted anything to do with Soviet POWs or Cossack turncoats fighting in German uniforms for the Third Reich. Then came the trio of crushing German defeats at Moscow, Stalingrad, and Kursk.

The first top Nazi to start changing his views of all Soviets as “sub-humans” was the Baltic-born German Alfred Rosenberg, Reich minister for the occupied Eastern Territories. He and his “Eastern politicians” were the first, besides the military, to realize that Nazi Germany could actually lose the war in the East. He also knew that millions of enslaved peoples saw themselves as fighting alongside the Germans, not for them, but were not willing to exchange the Red yoke for one of the swastika. It would have to be a genuine alliance.

As late as the summer of 1944, both Hitler and SS commanding general Heinrich Himmler denied this possibility, however, as did the powerful secretary to the Führer Martin Bormann and Prussian Regional Leader Erich Koch. Led by Rosenberg’s ministry on the crucial theme of needed manpower, however, even they slowly changed their minds since it was evident that Nazi Germany would be drowned by Red Army hordes if they did not.

Meanwhile, even against Hitler’s, the German Army in the East had begun training and equipping both dissident Cossacks and the so-called Russian Liberation Army (RONA) to fight the Soviets. The man who really stepped to the fore of his own volition in September 1942 was the East German career cavalry officer, Helmuth von Pannwitz, who well knew that during the Russian Civil War Cossack “wolves” had taken no Bolshevik prisoners and were eager to kill them again.

It was Pannwitz who approached German Field Marshal Ewald von Kleist about accepting the Cossack offer to fight with the Germans, and he was given a tacit but cautious approval to start their recruiting, training, equipping, and arming.

The Cossack Call

Recruiting began with those who had already come over and continued with the masses being held in German POW camps. Pannwitz’s goal was to build a first-rate cavalry division, while there remained an independent Cossack state within a self-governing Cossackia. This territory had been occupied by the Germans during 1942. He allowed his new charges to serve under their own officers and NCOs, over which was his hand-picked German cadre. Asserted one eyewitness, “He did not intend to make Germans out of the Cossacks.”

Pannwitz created a weekly newspaper titled The Cossack Call and insisted that his German cadres learn the more difficult Russian language. His former Soviet riders adapted to the German language far more easily.

He also restored unit church services and the recovery of dead bodies in the field for proper, Christian burial. Orthodox Russian chaplains were assigned to Cossack regiments, and the wearing of crosses and other religious ornaments was encouraged. Indeed, the Russian Orthodox Christmas was celebrated on January 6, 1944, with Pannwitz attending in full Cossack regalia.

Speaking at Hitler’s military headquarters, General Wilhelm Burgdorf doubtless summed up the feelings of more traditional Army officers at Pannwitz’s experiment saying, “Von Pannwitz looks quite savage with his crooked sword dangling in the scabbard down in front.”

Created a full Cossack general, Pannwitz was elected and re-elected as the field leader. He also formed a personal Cossack guard. In addition, he managed to save the famous Cossack Museum until it disappeared at the end of the war. He formed the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division on April 23, 1943, and on March 31, 1944, he established the Cossack Central Administration.

Cossack weaponry, including captured Tokarev automatic pistols, was issued by the Germans. The Cossacks also carried shaska sabers and wore their beloved black burka capes and Astrakhan and Kubanka fur caps.

Cossacks on the Front

Despite his obvious affinity for them, Pannwitz ruled his men with typical German toughness, with penalties ranging from solitary confinement in darkened cells and flogging to execution for more serious offenses. Nevertheless, he was granted honorary Cossack nationality on March 21, 1944.When Hitler personally awarded him a medal, the Führer asked Pannwitz slyly, “So how are things going with your Cossacks?” The Führer, despite the military’s secrecy, was well aware of what was going on. The 1st Cossack Cavalry Division was ready to go into action and was assigned by the new chief of the General Staff, Colonel General Kurt Zeitzler, to fight in the Balkans. Noted one authority, “The sturdy Cossack horses were ideal for the Balkan mountains.”

The main contribution of the Pannwitz Cossacks was soon to be freeing up German troops to fight elsewhere. Their Serbian-Croatian deployments included the September 1943 Operation Constantine to occupy areas formerly patrolled by the fascist Italian armed forces. Cossack units also took part in Operations Driving Hunt, Ball Lightning, and Autumn Storm. Cossacks were deployed to Croatia and Bosnia in the autumn of 1943. They also fought the communist partisans in Northern Italy from July 1944 to the end of the war. Stated one source, “The ‘North Croatian Fire Brigade’ emerged from the Cossacks.”

The regular German Army began changing its own initially poor assessment of the Cossack allies as they witnessed them fighting first as dismounted infantry and then as the mounted warriors they were justly famed to be. Still, the Cossack riders for the Reich had to wait until 1944 before being awarded the German military medals that they fully deserved and had earned in combat.

Cossack forces were sent to fight Yugoslavian communist partisans in September, 1943. With fully 270,000 men organized into 26 divisions, Tito was a threat that Nazi Germany simply could not ignore, especially as Churchill was then pressing for an invasion of southern Europe to forestall Stalin’s obvious drive to occupy the Balkans. Pannwitz led his beloved riders into combat against the partisans in Operation Fruska-Gora on October 12, 1943, in their first real baptism of fire. After-action reports ranked them from performed “admirably” to “with mixed success.”

The Cossacks also took part in Operations Wild Sow, Panther, Santa Claus, and then Schach in March 1944, as well as Rosselsprung, the latter designed exclusively to either capture or kill Tito. In addition to these formal combat field operations, the Cossacks performed valuable service patrolling the railroad line from the Croatian capital of Zagreb to Belgrade, the capital of the German-occupied country. One report stated that the Cossacks “performed exceptionally well, inflicting heavy casualties on Tito’s forces.”

Another observer reported that they were “skillful in staging ambushes, executing flanking movements, and rear attacks in contrast to frontal assaults in a war of movement without front lines. Avoiding frontal attacks, they struck at the enemy’s rear.”

SS in Name

In August 1944, Himmler wanted to incorporate the Cossacks under Pannwitz and General Timotei Ivanovich Domanov into his own Waffen SS, and he officially sanctioned the Cossack cause despite the fact that he was vehemently anti-Slavic. He recruited first Ukrainians, and then Cossacks.

Indeed, as early as December 24, 1942, Himmler’s administrative chief, SS General Gottlob Berger, had proposed the formation of an SS Cossack police unit, but other top SS leaders balked so the plan was dropped. Gunther d’Alquen, editor of the SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps), also acted as an agent of change to acquire the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division under the command of the ambitious Himmler.

Finally, on August 26, 1944, Himmler invited Pannwitz to meet with him aboard his personal command train to propose that the Waffen SS directly absorb all Cossack fighting forces. Taken aback, Pannwitz answered, “I have been in the Army since I was 15. To leave it now would seem like desertion.”

Switching tactics, the wily Himmler opted instead to have all Cossacks placed directly under Pannwitz’s command in a compromise agreement that would also see them set up in name only as the new SS XV Cossack Cavalry Corps, consisting of the old 1st and the new 2nd Divisions.

Thus, Himmler’s military vanity was at least partially satiated, and Pannwitz gained access to first-line SS supplies without actually making the Cossacks a part of the SS. It was, truly, a very fine distinction, and one that would not help either Pannwitz or the Cossacks when they fell under Allied control in 1945.

This shotgun marriage was consummated in September 1944; however, it was later characterized as “an unholy alliance that solved the supply problem” that had been dogging Pannwitz from the very start.

Valued by the Army for their scouting and reconnaissance abilities, the Cossacks jealously guarded their authorization and command function against Himmler’s rapacious SS, and one general asserted, “The Cossacks must be ruthlessly exploited to the last and sacrifice their lives for us, the best they have to offer. They are just good enough for that!”

Ironically, the Cossacks fought but one battle against the Red Army, and this took place on Christmas Day, 1944, in Yugoslavia. In bitter hand-to-hand combat against the Soviet 133rd Infantry Division near the Drava River, the Cossacks routed the Russians. The 11th Luftwaffe Field Division had been assigned to fight alongside the SS XV Cossack Cavalry Corps.

By February 1945, Pannwitz could take pride in the fact that he had accomplished his original goal with the formation of yet a third cavalry division. In March, his expanded corps took part in Operations Forest Fever and Forest Devil.

In September 1944 the Germans moved Domanov’s Cossack forces west into Fascist-controlled Northern Italy. Fighting as they went, the Cossacks journeyed hundreds of miles across Poland, Germany, and Austria before they arrived at Gemona, Italy, in the Friuli region. Quartered around Tolmezzo, they numbered 24,000 men, women, and even children, a nation on the move.

On April 28, 1945, Domanov was confronted by a delegation of Italian officers who insisted that he surrender his arms and leave Italy immediately. The Cossack colonel balked at surrendering his men’s weapons but began the exodus to Austria the very next day. They entered Austria via the Plocken Pass, with colorful Cossack mounted units leading the way. Having reached the Austrian village of Mauthe-Kotschach, the vanguard led the way to a settlement around Lienz.

Surrender to the British

Debating what to do next, it was mentioned that Field Marshal Alexander, who had been the British commander-in-chief against the Bolsheviks in 1918 in Courland on the Baltic Sea, might very well be the best and most sympathetic person with whom negotiations could be sought. Thus, a Cossack delegation of three men returned to Tolmezzo via the Plocken Pass route just traversed to meet with General Robert Arbuthnott, commanding officer of the British 78th Infantry Division.

Standing to deliver their plea, the Cossacks asked to be allowed to join General Andre Vlasov (of the Nazi-sponsored Russian Liberation Army) to continue fighting the Soviets. Startled, General Arbuthnott queried, “Who is General Vlasov?” After being told, the British general adhered to the Churchill-FDR demand of unconditional surrender enunciated at the 1943 Casablanca Conference: “You must hand over all your weapons without delay.”

He was then asked if the Cossacks would be considered Allied POWs. “No, that term only applies to those captured during the course of a battle,” the Britisher replied. British General Geoffrey Musson reiterated the same.

The next day, May 5, Musson visited Domanov, who was politely asked to move his masses to an area between Lienz and Oberdrauburg along the Drave (Drau) Valley, and under arms no less. This they did, willingly, during the second week of May, now after V-E Day. But some Cossack bands were still fighting five days after the German surrender.

Meanwhile, the Cossack high command simply ignored what little they did know of the Yalta agreements, merely assuming that the pre-1941 anti-Red Allies would welcome them in what they saw as the inevitable next phase of World War II—a joint Western Allied-Cossack holy war against land-hungry Communist Russia in Eastern Europe. If nothing else, the Cossacks were convinced that at least they would be granted political asylum by the democratic Western powers.

On VE-Day, May 8, 1945, two separate Cossack groups were being quartered in formerly Nazi Austria, close to the Slovenian border, then part of the former Yugoslavia that had been conquered by the Axis in April 1941. The initial group had been in northern Italy near Tolmezzo under the command of Ataman Domanov, with the second group of 18,000 of the XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corps dispersed across southern Austria under Pannwitz. As the accepted overall leader of these Cossack units, Pannwitz prepared to negotiate with British Field Marshal Harold Alexander.

On May 17 Field Marshal Alexander asked for instructions from London about what to do with his newly acquired, ready-made army of anti-Bolsheviks so far from their native steppes. On the 18th, General Arbuthnott also visited the Cossack camp at Peggetz, touring the huts, laughing and joking, and even taking a special interest in the Cossacks’ young cadet corps.

This happy mood turned somber with a sudden jolt, however, when it was announced by Domanov that all of the Cossacks’ dearly beloved horses had been stolen, to which the British general officer dryly answered, “There are no Cossack horses here! All the horses now belong to His Majesty the King of England, and the Cossacks are his prisoners.” With this rude shock, the cat was truly out of the bag.

“The Officers will be Shot”

On May 24, British V Corps General Charles Keightly was instructed by higher headquarters to hand over all Cossacks, without exception. “It is of the utmost importance that all the officers—particularly the most senior—are collected together, placed under guard, and that none of them escape…. The Soviet Forces place great importance on this, and consider without doubt—as a guarantee of good faith on the part of the British—that all the officers are handed over.”

Another put it more bluntly: “The officers will be shot,” by the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police.

A truckload of armed British troops arrived at the Cossack encampment on May 26 to seize all Cossack funds, some six million marks and an equal amount of Italian lire, deposited in the Lienz bank. The next day, May 27, the British demanded the surrender of all Cossack arms once more, and a rumor circulated across the camp that these would be replaced by British weaponry, a case of both self-denial and wishful thinking. More ominously, however, Arbuthnott issued an order declaring that all Cossacks found with weapons would be both arrested and subject to the death penalty. Resistance would be met with the order to open fire.

Debate among the Cossacks centered on believing the British would protect them, doubting their good intentions, and a failed option of sending the women and children away from the camps to avoid any unexpected and hostile developments. Pannwitz described the formal surrender scene in a letter to his wife, with enlisted soldiers laying down their weapons and officers allowed to keep their side arms, as per military tradition. Still, though, “the Cossack Corps was dead,” he lamented.

On May 28, Domanov ordered all his officers to assemble at Lientz and Peggetz in the belief that the British would return them there that same day. They were then convoyed away by cars, with 2,000 officers remaining in the Peggetz square. Some of the older ones wore their decorations earned fighting for their Little Father, the murdered Czar Nicholas II, in their part in the Great War, 1914-1916. Many wore the colorful and traditional Cossack garb.

These officers were put aboard a convoy of 60 British Army trucks. According to Huxley-Blyth, “The convoy consisted of four buses, 58 trucks, eight vans, and four Red Cross cars. The British escort consisted of 140 drivers and co-drivers, 30 officers, and five interpreters. To these must be added several jeeps with 25 light Bren machine guns and motorcyclists.” Shortly afterward, the convoy was also surrounded by tanks, allegedly to protect the officers from rogue German SS men in the nearby forests.

“They’re a grand lot, the English.”

Meanwhile, Domanov reached the suburbs of Oberdrauburg at the headquarters of the British 36th Infantry Brigade, where Musson bluntly shattered whatever illusions he had left: “I have to inform you, sir, that I have received formal orders to hand over the Cossack Division in its entirety to the Soviet authorities. I regret having to tell you that, but it is an order. Good day!” Later, even the ruthless NKVD secret police would cynically sneer, “They’re a grand lot, the English.”

Also on May 28, the officers were enclosed by barbed wire at an old former POW camp near Spital, where a full British regiment was stationed. The soldiers there had been ordered: “Any attempt at resistance will be firmly suppressed. If you are forced to open fire, you will shoot to kill. Any attempt at suicide will be prevented if it presents a danger to our men. If it does not, they will be allowed to commit suicide.”

The Cossack officers quite naturally panicked, tore their rank insignia from their uniforms, and destroyed their personal papers in a vain attempt to somehow stymie the dreaded Red secret police, the NKVD of Laventi P. Beria, the man even Stalin had cynically introduced to Joachim von Ribbentrop at the Kremlin in August 1939 as “My Himmler.”

That night, while Domanov dined with the British officers at their invitation, the first Cossack senior officer hanged himself. The next morning, May 29, trucks again arrived to take the officers to their new jailers, but they sat on the ground refusing to budge. Noted Lannoy, “For several minutes, the (British) soldiers beat and kicked the Cossack officers, raining blows down on them with boots, rifle butts, and fists. Some of the victims were beaten senseless, and the British used the opportunity to prod them with their bayonets. This treatment proved effective, and loading commenced.”

During the journey, several more officers killed themselves, while others escaped by jumping out of the trucks until after many hours the convoy arrived at the border of the Soviet Austrian Zone of Occupation at Judenburg near Graz in the Mur Valley. Unloaded from the trucks as more suicides occurred, it was here that the officers were finally joined by their overall commander, Pannwitz, elected by them to be their first and only foreign-born leader.

Vain Resistance

From Judenburg, all the senior officers were moved to Graz, then Baden outside Vienna, to the Red Army counterintelligence center for interrogations. Following that, they were transferred to Moscow’s notorious NKVD Lubyanka Prison, where the captured survivors of Hitler’s Berlin bunker also wound up, many for 10 years’ imprisonment. After the seizure of the officers, an order was issued on the evening of May 28 for all of Domanov’s NCOs to assemble at the Peggetz encampment the next day at 9 am. A proclamation was read: “Cossacks! Your officers have betrayed and misled you. They have been arrested and will not be coming back. You no longer have to believe in them or submit to their authority. You can now denounce their lies and freely express your convictions and hopes. It has been decided that all the Cossacks will be returned to their country.”

Pandemonium immediately ensued as the enraged NCOs surged forward in a body, declaring, “No! Our chiefs are not traitors, and no one has the right to dishonor them! All the Cossacks love and respect their officers. May they come back, and we will follow them to the end of the world!” Refusing to eat and throwing their foreign passports in the faces of the embarrassed British officers, the NCOs roared out, “How can you do this to us? We are not Soviet citizens! In 1920, you sent warships to the Dardanelles to save us from the Bolsheviks, and now you are going to hand us over to them!”

Black flags were hoisted in the camp, religious services were held, and the remaining horses were killed by their own grieving riders. On June 1, during and after the last religious service, a battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders Regiment arrived with another convoy of trucks. “Armed with rifles and pickaxe handles,” noted Lannoy, “the (Scottish) soldiers forced their way into the packed ranks, made a breach, and isolated about 200 Cossacks.”

Noted Major Davies’s official report, “The men formed a compact mass, tightly gripping one another, and it was necessary to force them apart one by one, starting at the extremities. The rest glued themselves even tighter together … But then panic spread … building a screaming pyramid that stifled those at the bottom…A man and a woman remained behind, dead by suffocation…. Once loaded, the trucks set off … and arrived at the railway line. There the Cossacks were unloaded and thrown into cattle cars with solid grills over the windows, and the doors were barred, while at the end of the train was a flat car on which were soldiers armed with machine guns.”

One can only guess at how the individual British officers and enlisted men felt about carrying out such a loathsome task. As a second group at Peggetz was pushed toward the trucks, many Cossacks cried out, “Get back Satan, Christ shall triumph! Lord, have mercy upon us!” One woman and a Tommy had a veritable tug of war over her child’s leg and body, “until, finally, the mother was exhausted, and the child was crushed against the truck…. The altar was overturned, and the priestly vestments ripped.”

Stated one source, “The soldiers redoubled their violence, and the rifle butts hammered down indiscriminately on men, women, and children. The priests and their assistants were forced to the ground in their vestments…. All were convinced—not without reason—that life in the Soviet Union would be worse than death.”

Pannwitz Stays with his Cossacks

The first train left with 1,252 Cossacks aboard and many more to follow. According to a witness named Olga Rotova, “More than 700 Cossacks were dead as a result of those operations, either crushed underfoot, killed by the British, or committed suicide.” The enforced evacuations continued up to June 15, 1945, and “during those 15 days,” asserted Lannoy, “22,502 Cossacks were packed into the cattle cars and sent into the Soviet Zone.… Several thousand managed to escape and sought refuge in the mountains, where they were mercilessly pursued by the British, who, helped by Soviet Special Forces, organized large-scale manhunts.” During three weeks in June, 1,356 Cossacks and Caucasians were recaptured, and of them, 934 were transferred to Judenburg and later to Graz, where, according to the British soldiers who escorted them, they were all massacred.

Meanwhile, the main body of Pannwitz’s XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corpsmen suffered a similar fate. There were 20,000 assembled on May 8 at the time of the general Axis Pact surrender, about 80 kilometers east of the Domanov Cossacks, between Volkermarkt and Wolfsberg. Sometime during May 9-10, British SOE (Special Operations Executive) officer Charles Villiers visited the headquarters of Pannwitz and immediately received the surrender of all his armed men, with the sole condition that they not be turned over to the hated communists. One of Pannwitz’s own staff officers had even served in Courland in 1918 against the Bolsheviks with the younger Harold Alexander, and thus all felt that political asylum among their former British allies in the Russian Civil War era was possible.

After sending the venerable field marshal a letter on May 9 and hearing nothing, Pannwitz decided to visit the latter’s headquarters himself. He was told by a British major that all his men would have to surrender all their weapons on May 11, and this proceeded apace without incident. Piles of 1st Cossack Division rifles mounted at the area assigned to the British Army’s 6th Armored Division at Feldkirchen, Austria. On May 15, Pannwitz and his senior officers learned that it was rumored that all of them were to be handed over forthwith to the Red Army. Given a possibility of escape with his own German officers, Pannwitz had nonetheless decided to stay with his beloved Cossack horsemen. Having joined his Cossacks voluntarily for a certain death by execution at the hands of the hated Bolsheviks, “Der Pann” as he was nicknamed, still wore his colorful Kuban papacha cap. True to form to his deeply held code of honor, he stated, “I have been with the Cossacks in the good times, and now I must remain with them in the bad.”

A Major von Eltz later testified that Pannwitz even briefly believed, “They were going to send the cavalry corps to Iran to fight communists who were trying to seize control of Azerbaijan Province … Pannwitz thought that the Cossack Cavalry Corps would be kept intact by the British, and transported to an island somewhere in the Pacific to be transformed into a sort of foreign legion.” These illusions were shattered and rumors caused dissension among Pannwitz’s own leadership cadre of German and Cossack officers. Nevertheless, on May 22 Pannwitz was reelected leader by his Cossacks.

Meanwhile, British and Soviet officers met at Wolfsberg and hammered out an official, bilateral document that defined the Allied view of the doomed Cossacks: They are “a special unit belonging to the SS anti-Partisan forces and comprising a collection of White bandits and counterrevolutionaries paid by the Germans.” At least 500 German officers and men escaped (some accounts assert with British connivance) before May 26, when the British informed Pannwitz that he had been removed from command. Pannwitz, 144 officers, and 690 other ranks who were Germans were also arrested, but even some of them managed to escape.

The End of an Era

On May 28, Pannwitz and his officers passed into Soviet hands along with Domanov’s officers. Lieutenant V.B. Englich, guarding the bridge at Judenburg, described the scene: “Von Pannwitz was very tall. He got out of the car, drew himself up to his full height and looked around…. He understood what was going on. He then advanced very slowly toward the Russians, with everyone looking at him…. He saluted them. It was almost as if he was taking part in a film.” Another official account stated that, upon seeing the Russians, he raised his hands in the air and cried out, “My God!”

Taken to Graz on May 30, he arrived at Baden on June 3, and then was taken by train to Moscow and his doom. Noted General Keightly afterward, “In the circumstances, our personal sentiments had to be disregarded. We had an enormous crowd of refugees on our hands, of all nations and in a critical condition.” Most Cossack senior officers were tried, convicted, sentenced to death, and executed. The remainder were imprisoned for long terms. The six most senior Cossack leaders, among them Pannwitz, were all hanged in the Lubyanka Prison courtyard at 10:45 pm on January 16, 1947.

In all, according to one official report, “2,126 officers were handed over to the Soviets, 12 (all of them ex-generals in the White, anti-Bolshevik armies from the 1918-1920 Civil War) were sent to Moscow for trial, 120 never arrived at Graz; 1,030 disappeared between Graz and Vienna, 983 who arrived in Vienna subsequently disappeared.” Overall, two million Russians, among them 50,000 Cossacks, were forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union in what one observer termed, “An outright appeasement of the Stalin regime on the part of the U.S. and the U.K., a denial of political asylum on a mass scale.” Conversely, asserted a Colonel Malcolm, “The political decision to repatriate the Cossacks was just, and the only one that could have been taken at the time.”

Others took the opposite view, as the controversy still resonates. One observer noted, “The Cossacks in German field gray who disappeared into the NKVD labor camps in 1945 took with them the remnants of a unique way of life. It will never again be resurrected. They disappeared into oblivion. Whether one saw them as patriots or traitors or simply as magnificent barbarians, it was indisputably the end of an era.”

British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery said, “In the area occupied by 21st Army group, there were appalling civilian problems to be solved. Over a million civilian refugees had fled into the area before the advancing Russians. About one million German wounded were in hospital in the area, with no medical supplies. Over 1.5 million unwounded German fighting men had surrendered to 21st Army Group on May 5 and were now POWs, with all that entailed.”

Noted German author F.W. von Mellinthin gave this assessment of the Cossacks’ last wartime combat operations: “Theirs was a desperate struggle in the final hours of the war, when Gen. von Pannwitz’ work reached its zenith and was plunged to its destruction. To the bitter end, the Cossack Corps did more than its duty and frustrated every effort of the enemy to cross the vital Drava sector.”

Despite the 1947 Moscow trials and Lubyanka Prison hangings, there were, in fact, few Cossack war criminals. Even Pannwitz’s conviction was overturned by the Russians after the fall of the former Soviet Union in 1991.

A sad tragic story

An obvious attempt to whitewash war criminals. The Nurnberg Tribunal had established that the SS was a criminal organization, therefore legally every repatriated Cossack was a criminal. Furthermore, in the Balkans and Italy, Cossacks were noted for marauding and absolutely brutal treatment of suspected Communists. Skinning people alive, gang rapes followed by execution, indiscriminate hangings, and tearing people apart by attaching their extremities to horses were common. Repatriation of Cossacks to the Soviet Union was actually the most kind resolution for the Cossacks. The majority survived. That would be an unlikely case had the Yugoslavs or Italians gotten hold of the Cossacks.

When it came to war crimes no one could compete with the Red Army.

Whether it be raping old women or cutting an unborn fetus out of the mother so a “better time” could be had….or just simply cutting off a young soldier’s genitals for whatever reason.

Europe’s refugees all headed to the West for a reason.

No this is actually the true story. There are many books, written in their own words to prove this. The internet is flooded with Russian propaganda calling Ukrainians Nazi’s for obvious reasons (3/13/2022). I can’t speak for their brutality but I would imagine this is true. My great-grandfather was the Commander of the Black Cossacks and fought in WW2. Yes, he did fight on the German side but he adamantly opposed. They threatened to Court Marshall him which would have meant execution in his case. The Volhynian Self-Defence Legion, created by the Germans/made up of Ukrainians actually lead jews out of the region through the forests to escape.

That the children were caught in this slaughter speaks harshly for the missteps at the Yalta conference, whatever else the Cossack soldiers were guilty of. That Britain and The United Stares, for that fact, seemed not to care or be oblivious to Stalin’s ruthless, murderous nature seems unforgivable. Especially when those, such as Gareth Jones’s firsthand account, tried to warn the world of the Soviet dictator’s atrocities to his own people before WWII.

Would it have been better if the women were repatriated and the children left to fend for themselves in the West? That makes no sense to me. Furthermore, no representative of a government think in terms of people, the think in terms of the needs of the country. I also do not understand the reference to Gareth Jones who died before WWII and whose writings have nothing to do with atrocities. He wrote about the 1932-33 famine which spread from Central Russia to Southern Russia and Ukraine and into Kazakhstan. The famine was the direct result of a drought and errors made by Central Planning. Has absolutely nothing to do with Stalin.

It may make no sense to you in 2021 but during WW2 several thousand polish Children had already been rescued from Iran of all places after fleeing there in fear of the Soviets And,No these were not jewish Children but Catholics. . You say the famine was the result of Central plannings inept handling. So the forced collectivisation of an entire nation was Central plannings Idea? Uncle Kuba was directly responsible for it,and he made damn sure that his name was never on any documents . To set yourself up as a Stalin Apologist is foolish stance to take.

Nothing to do with Stalin? This is an attempt to whitewash Stalin. I suppose that the murder of 22,000 Polish Officers and Intellectuals at Katyn was nothing to do with that butcher Stalin either!

NB The Russian Parliament admitted responsibility for the Katyn Massacre in 2010! Unfortunately Russia is back to telling lies again under ‘Tsar’ Putin!

There is a good book, where that sad event was described, as well as the life of a Russian family.

The book is called “Separated at Stavropol”. Nadia Stahanova, who lived through the ordeal, is describing, how their family has escaped the forced repatriation of Cossacks by English army, as Stalin made a deal with English. An unknown English officer has saved them:

“There were still some trucks going around picking up the

last Cossack officers. Vladimir, my husband, decided to get on one of them and go to the conference

after all.

He got dressed and all of us walked with him to a truck parked near our camping spot with the driver sitting inside the cab. There wasn’t anyone else around except a young English officer standing next to the truck.

He watched as Vladimir kissed our children good-bye and next made some signals with his hand as he watched the driver apprehensively. I got the message; he was pointing at the truck and making a clear “no” indication with his other hand. Then he pointed at the forest and nodded his head repeatedly.

Vladimir was about to climb on the truck when I told him what I had just observed. He reversed his path and headed to the forest with us following.

I glanced back once more and saw the English officer smiling approvingly.

God bless that unknown man! Thanks to him my children kept their father.”

This story breaks my heart for so many obvious reasons.

My Kuban Cossack grandfather and young teenaged father were involved in these events. My father passed seventeen months ago at 93, and I am just now learning so much about his youth that I never knew. He rarely talked about it, only late in life speaking a bit, but, even as he did well in life, we (his family) knew that he carried a very deep well of pain in him. And, a ferocious love for Russia.

Always interesting to see the Soviet propaganda in full bloom. Still do not understand even after 1991, that more of the truth of Stalin’s brutality has not come out in Russia. I suppose the presence of the incumbent has a good bit to do with it since his hands reek with the blood of others also.