By Earl Echelberry

Fresh from his capture of Fort Ticonderoga, Colonel Benedict Arnold in the summer of 1775 lobbied hard to the Continental Congress for authorization to lead an expedition to the lower St. Lawrence River and attack the English citadel at Quebec. He was prepared, said Arnold, “to carry the plan into execution and, with the smiles of Heaven, to answer for the success of it.” However, after careful consideration, Congress gave the command to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, a prominent New York landholder, with Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery, an ex-British captain, serving as his second in command.

Enraged, Arnold hastened to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and requested an immediate interview with General George Washington, commander-in-chief of the American forces. Washington was so impressed with Arnold’s bearing and fire that he authorized him to lead a second, complementary invasion of Canada. According to the best information available to Washington, the British had only one company at Quebec but could draw on an additional 1,100 troops from Montreal and other forts. Washington was afraid that even the weak force under General Sir Guy Carleton’s leadership might prevail against a Schuyler-Montgomery attack. To improve the invasion’s chance of success, Washington modified his original plan of attack to include Arnold’s diversionary force. He reasoned that if Carleton followed Arnold’s force, it would leave the way open for Schuyler, or if he blocked the Schuyler-Montgomery expedition, this would allow Quebec to fall into Arnold’s hands.

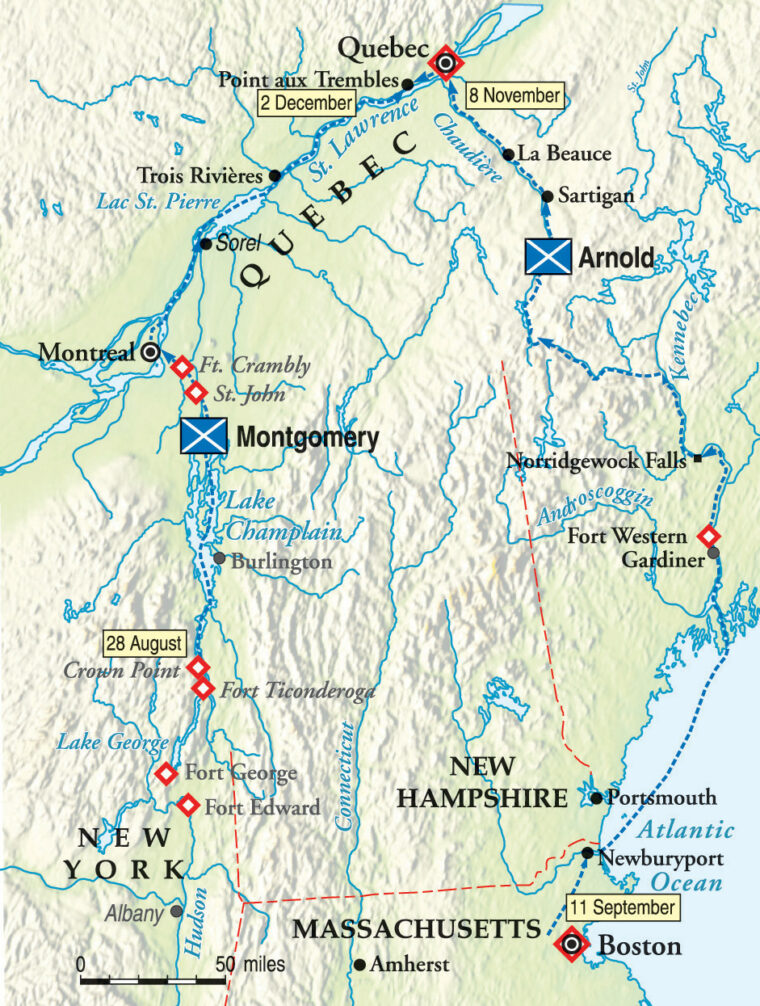

Washington’s Invasion of Canada

The logistical difficulties behind Washington’s plan were formidable. First, a force of about 1,100 men, the equivalent of a battalion including three rifle companies, would be required for the diversionary expedition. They were to land in Maine, where they would ascend the Kennebec River in flat-bottomed boats (bateaux), then negotiate a hard portage to the Dead River. From there they would pole on to Height of Land and finally move up the Chaudiere River to its mouth, opposite Quebec. This trek looked feasible on a map. However, plans, maps, and surveys all failed to take into account the heavy waterfalls, boiling rapids, killing portages over steep ridges, and normal run of accidents that men might encounter traveling by bateaux. Most of all, the plan failed to take into account the unforgiving climate the men would have to face.

Following the advice of Washington to “use all possible execution, as the winter season is now advancing,” Arnold threw himself headlong into the task of recruiting volunteers from the troops stationed around Cambridge. As a result of his zeal and promise of action, Arnold was able to assemble 10 companies of men from the New England colonies. To these numbers Washington added three additional rifle companies, two from Pennsylvania and the other one from Virginia, drawn by lot. The men were dressed like typical backwoodsmen, in buckskins, hunting shirts, and moccasins. Across the fronts of their broad-brimmed hats they had stitched the words: LIBERTY OR DEATH.

Arnold’s command was now ready to march. Speed was the primary requisite—the march must begin before summer slipped away. Washington had chosen wisely in selecting Arnold to lead the expedition. He was a man of stamina, enterprise, ambition, and daring, a natural-born leader but not a driver, a man with complete confidence in his native ability.

Organizing the Army

Arnold placed Captains William Hendricks and Matthew Smith in charge of the two Pennsylvania rifle companies and Captain Daniel Morgan was in charge of the Virginians. The first battalion was headed by Lt. Col. Roger Enos, with Major Jonathan Meigs serving as his assistant. The first battalion comprised four companies headed by Captains Thomas Williams, Henry Dearborn, Oliver Hanchet, and William Goodrich. The second battalion was led by Lt. Col. Christopher Greene and Major Timothy Bigelow. The second battalion’s company commanders were Captains Samuel Ward, Jr., Simeon Thayer, John Topham, Jonas Hubbard, and Samuel McCobb. A detachment of 50 artificers led by Captain Reuben Colburn joined the expedition prior to its ascent of the Kennebec River. The expedition also had a surgeon, Dr. Issac Senter, along with a surgeon’s mate, two assistants, two adjutants, two quartermasters, and a chaplain, Samuel Spring. There were also five “unattached volunteers,” including 19-year-old Aaron Burr (who was accompanied by a teenage Abenaki Indian princess nicknamed “Golden Thighs”), Matthias Ogden, Eleazer Oswald, Charles Porterfield, and John McGuire.

Since Carleton had stripped off troops to reinforce General Thomas Gage in Boston, prospects of success seemed excellent as Washington addressed Arnold’s men and enjoined them to respect the rights of property and freedom of conscience. He also composed an address to the Canadians: “The cause of America and of liberty is the cause of every American whatever may be his religion or his descent. Come, then, ye generous citizens, range yourselves under the standard of General Liberty, against which all the force and artifice of tyranny will never be able to prevail.” To Arnold, Washington advised, “Upon the success of this enterprise, under God the safety and welfare of the whole continent may depend.”

A Challenging Upriver Trek

On the dangerously late date of September 19, Arnold sailed from Newburyport with approximately 1,100 men. They landed three days later at Gardinerstown, where Arnold arranged for a little fleet of coasters and fishing boats to carry his men to the mouth of the Kennebec River. The next day the fleet of boats made its way up the twisting and troublesome river for 49 miles to Reuben Colburn’s shipyard. As the landsmen disembarked, overjoyed to have solid ground underneath them again, they saw the bateaux that were to be their transportation up the Kennebec River. Above the bay at Fort Western, Arnold’s men and supplies were transferred to the bateaux. Arnold spent the next several days organizing his army for its 385-mile plunge through the wilderness. On the 25th, two advance reconnaissance patrols were sent upriver to clear a path. A day later the second battalion, led by Greene and Bigelow, followed with three companies of musketeers. Meigs followed with part of the first battalion, while Enos and the remainder of the men made up the rear guard. Each company carried 45 days’ worth of provisions.

From the very first, the going was hard. It took the main body two days to cover the first 18 miles upriver to Fort Halifax. At Taconic Falls the men faced their first challenge, a portage of half a mile around the falls. On aching and raw shoulders the men hauled over 65 tons of supplies, before hoisting each bateaux (weighing 400 pounds apiece) and carrying them to the other side of the falls. The boiling rapids of Five Miles Falls came next, followed by the dangerous half-mile approach to Skowhegan Falls.

In wet and frozen clothes, they continued. Traveling through the heavy rain, they reached Skowhegan Falls on October 1. Getting the boats up the falls seemed impossible, for the crevice that split the face of the rock was steep and treacherous. Still the men trudged onward, dragging their awkward bateaux. At the top, the boats were patched and reloaded, and the army prepared to move forward. On October 4 they passed the last vestiges of civilization. Taking leave of the settlements and houses at Norridgewock, they spent the next three days navigating Norridgewock Falls.

Rowing, dragging, and sometimes carrying their craft, they moved past rapids and cataracts and across morasses and craggy highlands. With each portage, more and more supplies were ruined. Checking his position, Arnold found that he had spent twice the time allotted for the trip, and he was still on the Kennebec River. Realizing that half the provisions already had been spent, Arnold cut daily rations to half an inch of raw pork and half a biscuit. It was not long before Dr. Senter began to note rampant dysentery and diarrhea among the men.

On October 9 the column pushed forward toward the Curritunk Falls, the next major portage. Having reached the Great Carrying Place, an advance party of seven men was sent out to mark the shortest portage from the Kennebec to the Dead River. After eight miles of portage through forests of pine, balsam fir, cedar, cypress, hemlock, and yellow birch and four miles of rowing across three ponds, they reached the brown waters of the Dead River on the 11th. The rest of the men followed, carrying their boats, baggage, stores, and ammunition, and the next day the expedition reached the Dead River.

Cutting Down the Invasion Force

Arnold had determined that the distance from the mouth of the Kennebec to Quebec was only 180 miles, requiring 20 days of travel. Although he had provided food for 45 days, his army had been on the journey seven days longer than he had calculated for the whole march and had come less than halfway. Provisions were running low, and his men were now reduced to boiling rawhide and candles into a gelatinous soup. An unfortunate dog that someone had brought along as a mascot was killed and “instantly devoured” by the hungry trekkers.

By October 24, realizing that something needed to be done, Arnold ordered Greene and Enos, commanding the two rear divisions, to send back as “many of the poorest men of their detachment as would leave fifteen days provision for the remainder.” Greene and Enos called their officers together to determine whether they should turn back. “Here sat a council of grimacers,” said Senter, “melancholy aspects who had been preaching to their men the doctrine of impenetrability and non-perseverance.” While Greene’s men voted to march on, Enos started to the rear with about 300 men, his own division plus stragglers and the sick from other divisions. The retreat was accomplished in 11 days of relatively easy travel.

Reaching Quebec

After 17 portages, the main body arrived at Height of Land, gateway to the Chaudiere River. The gaunt, starving, half-dead men, under the load of the few remaining bateaux, fought their way through a chain of ponds and up the granite walls of the snow-covered Height of Land. The mountains had been clad in snow since September. Now with the winter wind howling around them, the weary men dropped to the ground; some died within minutes. Many of his companions, wrote one soldier in his diary, “were so weak that they could hardly stand on their legs. I passed by many sitting wholly drowned in sorrow. Such self-pitying countenances I never before beheld. My heart was ready to burst.”

The army was reduced to fewer than 700 men in near danger of starvation. Undaunted, Arnold pressed on, hoping to obtain food for his weakened and famished men. On October 27, at the Chaudiere, Arnold received heartening news. Two Indians brought him a letter saying that the people of Quebec rejoiced at his approach and would join the Americans in subduing the British forces. Provisions were pooled, and each man was issued five pints of flour and about two ounces of pork to sustain him for the last 100 miles before the army reached the Canadian settlements.

In the men’s eagerness to descend the rocky channel of the Chaudiere, three boats laden with ammunition and precious stores overturned. With starvation still ahead of them, the army pressed toward the St. Lawrence River. As they proceeded down the Chaudiere, they came upon a French-Canadian settlement, where they were charitably received and given a heaven-sent meal of fresh vegetables and beef. “We sat down,” Senter noted, “ate our rations, and blessed our stars.”

Washington had told Arnold to send an express messenger back to Cambridge if problems arose during the march. From Arnold’s optimistic report stating that his provisions would last another 25 days and that he expected to reach the waters of the Chaudiere in 10 days, putting him within striking distance of Quebec, Washington assumed that Arnold would be in Quebec by November 5. When that day came, Arnold was facing new problems. He had only 650 men left, many of them shivering in their shirts from the winter winds.

On November 8, in an epic struggle against hunger, weather, and terrain, Arnold’s men pushed down the last stretches of the harrowing Chaudiere River. Finally, on November 9, the ragged band of men emerged from snow-covered forests onto the south bank of the St. Lawrence. Their feet shod in raw skins and dressed in tattered clothes, the men marched upriver to Point Levi on the Isle of Orleans. They had taken 45 days, not the estimated 20, to cover 350 miles. But they had arrived, and even though they were too weak to make an effective attack on the Quebec citadel, they were going to attack nonetheless.

Crossing the St. Lawrence River

In peasant disguise, Carleton had successfully evaded Montgomery in Montreal. Traversing the countryside, he arrived in Quebec on November 19 and at once took command of the British forces stationed there. During the French and Indian War, Carleton had served under Brig. Gen. James Wolfe and had witnessed the rashness of French General Louis Joseph de Montcalm de Saint-Veran in risking battle outside the walls of Quebec. Carleton had his men burn all the boats on the St. Lawrence River to prevent Arnold from ferrying troops across the river.

Faced with yet another stumbling block, Arnold set his men to the task of obtaining canoes, dugouts, and scaling ladders. After allowing the men time to recover their strength, Arnold finally was prepared to cross the mile-wide St. Lawrence. His plan was to make a night crossing and land at Wolf’s Cove. Using the same rugged path that Wolfe had used during the French and Indian War, Arnold intended to climb to the Plains of Abraham. From there the Americans would boldly challenge the garrison. Just as Montcalm had been drawn into battle outside the garrison’s perimeter, Arnold expected Carleton to make the same mistake.

By November 13 Arnold had enough boats to transport his army, except for about 150 men whom he left at Point Levi. At 9 pm, Arnold began the river crossing with 30 vessels. Moving fewer than 200 men at a time, Arnold managed to slip past two armed British vessels three times before daybreak on the 14th. Landing at Wolfe’s Cove without cannon and short of ammunition, Arnold led his 500 half-armed musketeers up the steep path to the expanse of land known as the Plains of Abraham, a mile and a half from the city. Marching to the walls of Quebec, Arnold ordered his band to give a cheer. The noise seemed to provoke curiosity inside the town, but nothing more. Inside, Carleton, having served as a subaltern with Wolfe, wasn’t going to be tricked by the same stratagem the British had used at Quebec a few years earlier.

Montgomery Links up with Arnold

Doubting the sympathies of the inhabitants, Carleton kept his men inside the fortress. That evening Arnold sent a messenger under a flag of truce to demand the fort’s surrender. Arnold knew his bluff had been called when the British fired upon his emissary. Standing before the towering walls of the great fortress, Arnold realized that his force was far too weak to attempt a move against the great natural citadel. His only hope was that the inhabitants within the walls would rise, but there were no signs of this. Lacking the firepower to mount an attack—his men had only five rounds apiece—and realizing that it was useless to attempt to besiege the town without cannons, Arnold exercised his only remaining option and called for an orderly retreat to Pointe aux Trembles to await the arrival of Montgomery.

Even before Montgomery prepared to leave Montreal, he had reluctantly reached the conclusion that the only way to conquer Quebec was by assault, regardless of the loss in lives that such an attack would entail. He reasoned that a siege would be a long and drawn-out affair, ending when the ice thawed in the spring and allowed British reinforcements to navigate down the St. Lawrence River.

Montgomery’s command consisted of little more than 800 men, which he needed to both garrison his conquests and attack Quebec. As the cold winds of November blew, Montgomery sent word to Arnold that he would soon join him at Point aux Trembles. On November 26, Montgomery set out with 300 men to join Arnold before the gates of Quebec, leaving St. John’s under the command of Captain Marinus Willett and entrusting Montreal to Brig. Gen. David Wooster.

On December 2, Montgomery linked up with Arnold, bringing fresh clothes, artillery, ammunition, and provisions of various kinds captured at Montreal. Assuming command of Arnold’s famished veterans, Montgomery’s combined force consisted of about 1,000 American troops and a volunteer regiment of about 200 Canadians. On December 5, Montgomery’s force advanced toward Quebec through a fresh snowfall. Montgomery set up his headquarters on the Plains of Abraham between St. Roche and Cape Diamond and posted Arnold’s men in the half-burned suburb of St. Roche.

A Confident Carleton

Intercepting messages between the American commanders, Carleton was well-aware of the strength and disposal of the colonial forces. After Arnold’s futile challenge, Carleton had strengthened his force by having Lt. Col. Allan MacLean force-march 400 recruits from Sorel. With these additional men, Carleton now had 1,200 men at his disposal. He confidently awaited Montgomery’s advance.

As the fierce Canadian winter set in, snow began to pile up and a raw, blistering wind howled on the shelterless heights around Quebec. Realizing that his ammunition and supplies would not last long enough to starve Quebec into submission, Montgomery sent a peasant woman into the fort with an ultimatum demanding the citadel’s surrender. To emphasize his demand, he advanced riflemen near the walls of Quebec. But Carleton again refused to capitulate, saying that he would not parley with rebels. To emphasize his point, he had a drummer boy take the letter from the woman’s hands with a set of tongs and toss it, unread, into the fireplace. As the American sharpshooters picked off sentries in exposed positions, Montgomery attempted to throw up earthworks and to raise a battery of six 9-pounders and a howitzer.

The small shells that were thrown by the battery did no essential injury to the garrison. Under a second flag of truce, Montgomery tried again to coerce Carleton to surrender. Again he was rebuffed. It was plain to Montgomery that his bluster and guns had failed to make any visible impression on Carleton. With no heavy guns to batter the walls of Quebec, food running short, and enlistments about to expire, Montgomery prepared for an all-out assault. Montgomery and Arnold decided to wait until the next snowstorm to conceal their movements from the town, then attack the cliff city. Ordering a general review on Christmas night, Montgomery told his men bluntly, “To the storming we must come at last.”

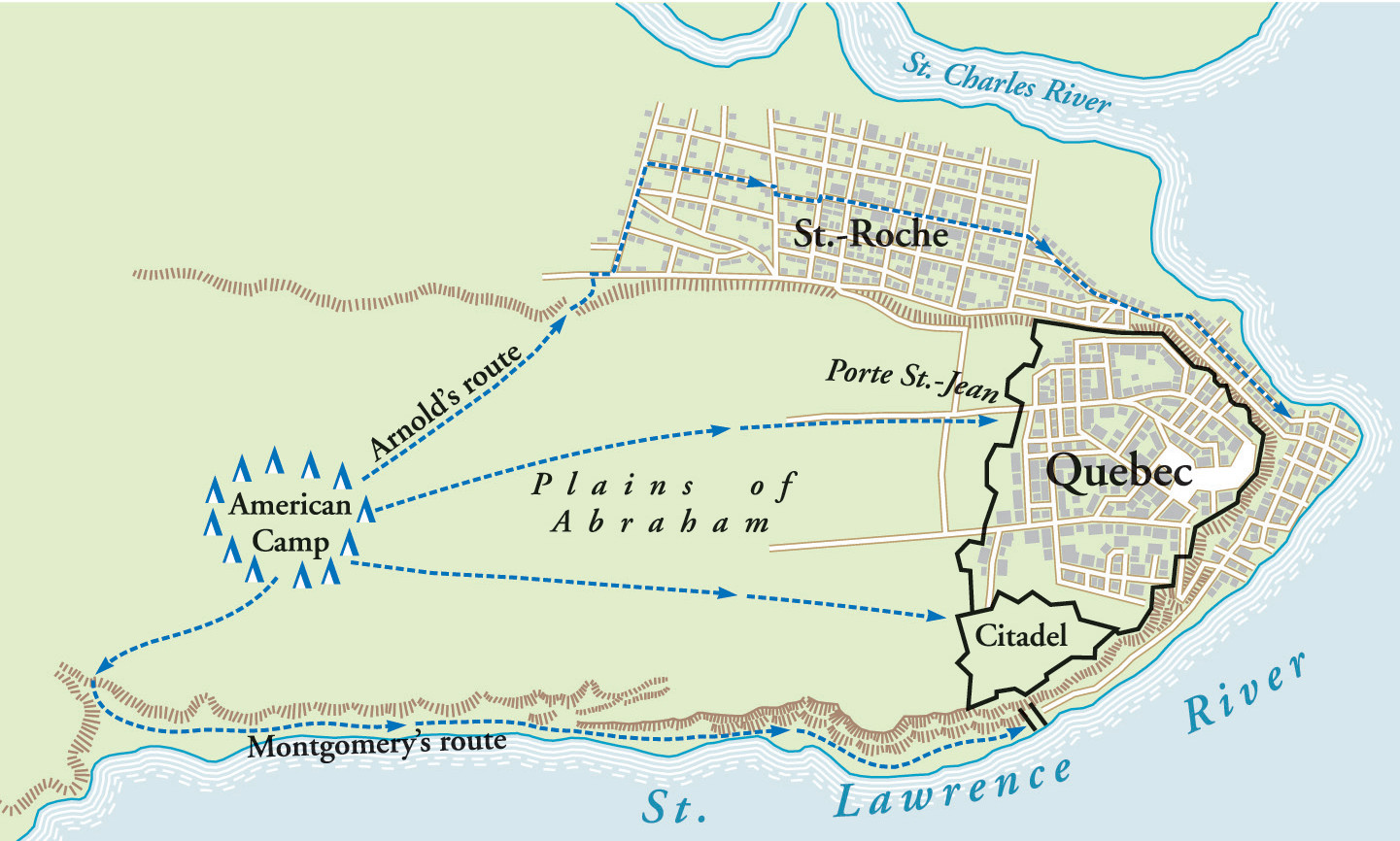

The Plan of Assault

Carleton was a capable commander who knew what had to be done for Quebec to hold out. Sensing that Montgomery’s attack would be directed against the lower town, he set his defenses accordingly. Montgomery was also a man of capacity, but he lacked Carleton’s principal advantage—the great triangular stone citadel. Instead, Montgomery conceived a bold plan for a predawn attack. Following the road that ran along the base of the towering cliffs, Montgomery would lead one division from the west, while Arnold would lead a second attack from the north. Joining forces in the lower town, they would then drive up the slope into the upper town. At the same time, feinting movements were to be launched against the western walls facing the Plains of Abraham.

Preparations were rushed. Men hammered together scaling ladders and armed themselves with hatchets and spears, expecting hand-to-hand combat. Montgomery issued a proclamation designed to inspire his troops: “The [Americans] flushed with continual Success, confident of the Justice of their cause, and relying on that Providence which has protected them, will advance with alacrity to attack the works incapable of being defended by the wretched Garrison behind them.” Carleton, expecting an attack, kept flares burning all night along the fortress walls.

The Attack on Quebec

On the afternoon of Saturday, December 30, snow clouds gathered and high winds moved in from the northeast. Final orders were issued and the men prepared to launch the attack, which would begin at 2 am. By early morning on the 31st, with a blizzard howling around Quebec, the two false attacks were launched ahead of schedule. Colonel James Livingston’s small Canadian force approached the St. John’s Gate but quickly broke and ran, while Captain Jacob Brown’s Massachusetts men delivered a sustained fire against the Cape Diamond bastion without any significant effect. The British garrison, now alerted, began beating drums and ringing church bells. Officers ran though the streets of Quebec turning out their troops. Quickly the barricades in the lower town were manned.

In the early morning hours British Sergeant Hugh McQuarters was alerted by the lights of lanterns descending from the Plains of Abraham, as well as signal rockets. Looking along the track that led east from Wolf’s Cove, he soon detected movement. Within the swirling snow the movement became clearer, finally resolving itself into a body of men in formation cautiously pushing forward. In a blinding snowstorm, Montgomery’s men descended from the Plains of Abraham and passed safely around Point Diamond. Upon reaching the first barrier and finding it undefended, Montgomery sent messengers urging his men to hurry along. Moving forward through a narrow defile, he spotted a log house containing loopholes for musketry and two 3-pounders loaded with grapeshot. Inside the blockhouse, McQuarters awaited the enemy’s approach with lighted fuses.

Montgomery waited until about 60 men joined him. Then, urging his men forward, he rapidly advanced on the battery. McQuarters, in charge of the loaded cannon, held his fire. The Americans closed to within about 50 yards and halted in the blinding snow. Trying to make out the nature of the obstacle ahead, Montgomery slowly moved forward, followed by two or three others. McQuarters dropped his match to the breech of the cannon. A sheet of flame spewed forth, and a devastating blast of grapeshot tore through the advancing Americans. Montgomery was instantly cut down, along with most of his advance party, leaving the cluster of bodies lying dead in the snow. The balance of the men fell back in panic. Morale shattered, Colonel Donald Campbell assumed command and, leaving the bodies of the slain Montgomery and his men where they fell, ordered an immediate retreat.

Arnold, meanwhile, led his troops in single file on a path along the St. Charles. They passed the Palace Gate unchallenged. No sooner had the main body passed the Palace Gate, however, than the city bells began to ring and the drums beat a general alarm. From the ramparts above came a tremendous fire. Pelted by musketballs, Arnold and his men ran the gauntlet for a third of a mile. Driving forward into the narrow street, they came upon a barricade mounted with two guns. A musket ball struck Arnold in his left leg, pitching him forward into the snow. Trying to continue the charge in spite of a broken leg, he was finally led to a military surgeon a mile from the battle.

Morgan assumed command, and his men rushed to the portholes in the first battery and fired into them while others mounted ladders and quickly carried the battery. Greene, Bigelow, and Meigs soon joined Morgan at the head of his Virginians and a few Pennsylvanians, swelling their meager force to 200 Americans. They quickly pressed down a narrow lane toward the second barricade at the extremity of Sault au Matelot. Upon reaching the barricade, Greene made a heroic effort to carry it, but upon scaling its walls he was met with a wall of bayonets. The Americans were exposed to heavy fire from both sides of the narrow street. Unable to push forward or retreat, the attackers were quickly overpowered and forced to surrender. A few individuals managed to make their way back to their own lines, but Morgan and 425 other colonials were taken prisoner. Another 60 were killed outright.

The Campaign into Canada Crumbles

The fight for Quebec was over. Arnold and Montgomery’s attempt to seize Canada died during the howling snowstorm on December 31. Everything had conspired against its success. Arnold’s long trek through the wilderness and Montgomery’s delay at St. John’s placed their armies before Quebec ill-equipped to either breach the citadel’s walls or mount a siege. Their ensuing attack resulted in Montgomery’s death and Arnold’s wounding. Recuperating quickly, Arnold assumed command of the remnant army outside Quebec. Stubbornly attempting to maintain the siege, he began pulling his forces together, checking the flight of deserters, and imploring the lethargic Wooster, Montreal’s commander, to send as many men and equipment as he could spare. Wooster replied that he could send little help. This, along with the refusal of the New York regiment to reenlist, caused Arnold’s chances for a renewal of the conflict to disappear.

Meanwhile, Carleton bided his time safe inside the walls of Quebec, allowing the winter cold and sickness to further reduce the American force. General John Thomas replaced Wooster and assumed command of the Canadian expedition. Shortly after his arrival in May 1776, British ships sailed up the St. Lawrence, their decks crowded with the scarlet and white of the British Army and the blue and white of 2,000 German mercenaries. This eliminated any hope the Americans had of capturing Quebec. Thomas issued orders for a retreat toward Montreal. The colonial army began a slow withdrawal toward Richelieu, St. John’s, Ile aux Nois, Crown Point, and Ticonderoga.

At St. John’s, Brig. Gen. John Sullivan replaced Thomas, who had died of smallpox during the retreat. Sullivan briefly considered making a stand at Montreal, but decided against it. Arnold wrote to Schuyler, “The junction of the Canadians with the Colonies—an object which brought us into this country—is at an end. Let us quit then and secure our own country before it is too late. There will be more honor in making a safe retreat than hazarding a battle against such superiority which will doubtless be attended with the loss of our men and artillery. These arguments are not urged by fear for my personal safety. I am content to be the last man who quits the country.”

Arnold assumed charge of the rear guard and waited until the British army came into view before firing off one last pistol shot and joining the retreating soldiers in boats ferried south to Isle aux Noix. From there, the remnants of Montgomery’s and Arnold’s commands fell back to Crown Point. Strangely, Carleton broke off his pursuit and withdrew, leaving the shaky garrison at Ticonderoga in American hands. The ambitious Canadian campaign had ended in defeat, but once again the American forces had lived to fight another day.

Did Arnold’s march shoot deer and moose for food? Especially interested in deer