By Donald Roberts II

The year 1776 ended on a high note for Washington’s Continental Army despite its earlier devastating defeats on Long Island and Manhattan. Although the long retreat into Pennsylvania had exhausted his soldiers, Washington led the army to a triumph at Trenton followed by another one at Princeton as the year tipped into 1777.

The back-to-back American victories were enough to make His Majesty’s soldiers take a fresh look at the overall military ability of their colonial adversaries. For one, British Lt. Col. William Harcourt wrote, “They [Americans] seem to be ignorant of the precision, order, and even of the principles, by which large bodies are moved, yet they possess some of the requisites for making good troops, such as extreme cunning, great industry in moving ground and felling of wood, activity and a spirit of enterprise upon any advantage. Having said this much, I have no occasion to add that, though it was once the fashion of this army to treat them in the most contemptible light, they are now become a formidable enemy.”

British Formulate Plan for 1777 Campaign

By the beginning of 1777, it had become apparent that a more coordinated effort would be needed to defeat the American armies. Possibly for the first time, most British leaders began to realize that the rebellious colonies were a huge expanse without a central nerve center vital to the success of their revolt. British commanders had also come to understand that the Americans seemed capable of raising new armies wherever they were needed. As a result, British strategists formulated a plan for the 1777 campaign they hoped would bring an end to most of the coordinated American war efforts.

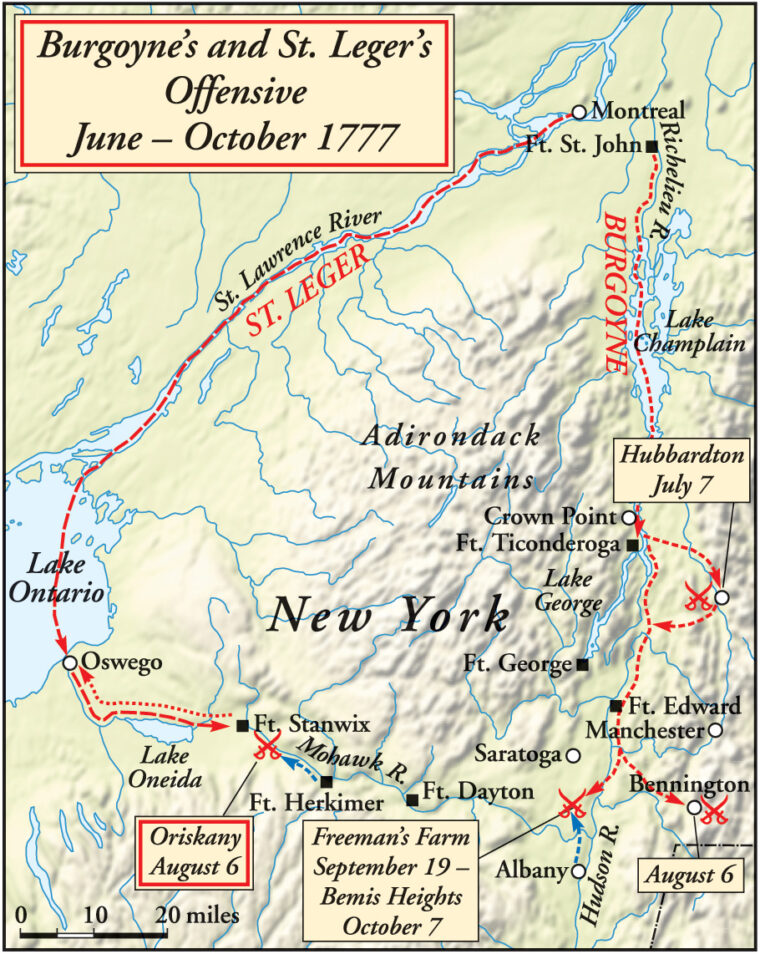

Strategic plans from two British generals were submitted for approval to Lord George Germain, Colonial Secretary of State. The first came from General Sir John Burgoyne, who was second in command of British troops in Canada under General Sir Guy Carleton. Burgoyne’s plan (under which he would serve as commander) called for a two-pronged attack from Canada against Albany, NY. His strategy included at least some support from General Sir William Howe, who was in charge of the main British army garrisoned in New York City. Burgoyne’s invasion, if successful, would separate New England from the Middle and Southern colonies, hopefully weakening any coordinated efforts by the Americans to continue the war.

General Howe, who submitted the second strategic plan for 1777 to Germain, wanted to launch attacks from New York against Boston and Albany. However, Howe’s major goal was to begin the campaign season with an offensive directed against the American capital at Philadelphia. He planned on supporting Burgoyne with a token force of some 9,000 men, to “facilitate in some degree the approach of the army from Canada,” to appease Germain, who was in favor of an attack on Albany.

In the end, Lord Germain approved both plans for the 1777 campaign. Consequently, he received criticism for endorsing a strategy that divided his forces and allowed them to move in opposite directions at the same time. In Germain’s defense, however, neither Howe nor Burgoyne wanted or expected much in the way of support from each other.

Because Burgoyne and Howe maintained their own operational agendas, communication between them as well as with Germain was practically nonexistent before and during each general’s campaign. Terms like “co-operation” and “conjunction” filled the written plans before the offensives, but these concepts were considered less important once the campaigns were initiated. The main reason was that Germain, Burgoyne, and Howe believed that massive Loyalist support would surface in Pennsylvania and New York to swell the ranks of the invading British forces. The architects of the British campaign of 1777 believed they would be able to squelch the revolution by the end of the year.

Local Loyalist support for British forces was on the mind of American General Philip Schuyler as well. Schuyler, who commanded the Northern Department, was not certain who the majority of the American population in the region would support should Burgoyne invade down the Hudson River. With this in mind, Schuyler prepared as best he could for an enemy invasion from Canada. He positioned his forces along the Hudson with a concentration of troops at Fort Ticonderoga, which guarded the northern approach to Albany along the Lake Champlain/Lake George/Hudson River route. Another American force was garrisoned at Fort Stanwix, which guarded the approach into the Mohawk River Valley from Lake Ontario.

Commanding the 2,500 troops at Fort Ticonderoga was Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair. He and Schuyler knew that holding “the Gibraltar of America” in the face of a superior force would be impossible. As a result, both officers agreed that the fort would be held for as long as possible and then abandoned. St. Clair was instructed to withdraw his men at the last minute across the river to Mount Independence, which was a better defensive position.

On the other hand, Fort Stanwix was to be held. This fort, built on the Mohawk River in 1758, had been allowed to decay until the newly appointed commander, Colonel Peter Gansevoort, and his 450-man 3rd New York Continental Regiment arrived to restore it. Then, as news of Burgoyne’s invasion filtered throughout New York, another 250 reinforcements arrived from Colonel James Wesson’s 9th Massachusetts Regiment along with 50 New York State militiamen.

On June 13, Burgoyne’s primary invasion force left Fort St. John on the Richelieu River for the advance up (southward) Lake Champlain toward the head of the Hudson River near the southern end of Lake George. In all, he commanded some 12 regiments of infantry along with various attached units including 400 Indians. His combined force numbered 7,200 troops.

Burgoyne’s secondary or diversionary invasion was commanded by Lt. Col. Barry St. Leger. Burgoyne had nominated him to command the expedition and King George III had approved the selection. St. Leger was a veteran of the French and Indian War and had come to understand Indians, especially their methods of combat. To command an independent corps was an honor, and he was determined to prove that he was worthy of such esteem. St. Leger’s primary objective was to envelop Albany from the west while drawing away as many enemy forces as possible from defending against Burgoyne’s primary attack down the Hudson.

For weeks St. Leger assembled his force for the pincer attack into the Mohawk Valley and toward Albany. He organized a diverse group at Oswego on Lake Ontario. He had 200 regulars from the 8th and 34th Regiments as well as a detachment of a hundred Hessian jägers (German light infantry). Included in the force were a company of Sir John Johnson’s Royal Greens (Loyalists) and a company of Loyalist rangers commanded by Colonel John Butler. St. Leger added four small artillery pieces as well as a large number of Canadian militia and axmen. Joining this mixed fighting force was Chief Joseph Brant with a thousand warriors from the Iroquois Nation. In all, St. Leger commanded over 2,100 combatants for his advance against Fort Stanwix and Albany.

A Swift but Vigilant March Against Fort Stanwix

By July 5, Fort Ticonderoga fell to Burgoyne’s attack, and his forward elements approached Fort George (formerly Fort William Henry) and Fort Edward. Meanwhile, the local intelligence ring reported to St. Leger that Fort Stanwix was in serious decay and garrisoned with only a handful of men. This information was wrong, but it did not sway St. Leger to underestimate his enemy. He left Oswego on July 26, deploying his forces with good tactical sense for a swift but vigilant march against Fort Stanwix.

Chief Brant’s Indians spread out in columns to scout ahead of the advance guard, with a number deployed as flankers. Marksmen from the Royal Greens made up the advance guard while the remaining troops aligned in double columns that formed the main body. Moving carefully but swiftly, St. Leger made about 10 miles a day. He soon learned from his scouts that even this pace was not fast enough to reach Fort Stanwix before the American reinforcements. Concerned, St. Leger immediately sent forward a force of 30 regulars from the 8th Regiment and about two hundred Indians led by Brant to try to intercept the American column and prevent it from reaching the fort.

On August 2, the expected reinforcements reached Fort Stanwix. Soldiers immediately began to offload the provisions from the boats, while the final elements of Colonel Wesson’s Massachusetts Regiment moved behind the walls of the stockaded fort. Suddenly, scores of Brant’s Indians swarmed out of the surrounding wilderness and attacked the boatmen at the landing, killing and wounding several of them.

This surprise appearance of hundreds of hostile Indians served to justify Colonel Gansevoort’s earlier decision to send the wives and children of the garrison back to their homes. In a letter, Gansevoort had written that “these mercenaries [Indians] of Britain came not to fight, but to lie in wait to murder; and it is equally the same to them, if they can get a scalp, whether it is from a soldier or an innocent babe.”

During the next day, St. Leger appeared with his main body. Parading his forces, he hoped to intimidate the Americans into surrendering the fort without a fight. This show of force only served to strengthen the Americans’ determination to defend their position. Consequently, St. Leger sent Captain Gilbert Tice under a flag of truce to the fort with a proclamation that promised “wrath” and “devastation, famine and every concomitant horror” to those who continued to oppose the forces of “His Majesty.” In reply, Colonel Gansevoort had Tice escorted to the fort gate and dismissed back to the wilderness.

Gansevoort continued to fly a Continental flag in defiant response to St. Leger’s demands. The American commander later wrote, “It is my determined resolution to defend this fort and garrison to the last extremity, in behalf of the United American States, who have placed me here to defend it against all their enemies.” Gansevoort knew that every day he delayed St. Leger’s force improved American chances to defend Albany.

In response to Gansevoort’s bravado, St. Leger decided to lay siege to the fort rather than conduct a direct assault against its defenses. To St. Leger, a siege would serve to cut Gansevoort’s communications with Albany just as well as an assault on the fort itself. St. Leger deployed his forces so the American position was nearly surrounded. The regulars and St. Leger’s main camp were positioned along the high ground north of the fort. To the west were the Loyalist units. Chief Brant’s Indians were arrayed along a line south of the Mohawk River and along a low-lying swamp to the east.

During the next two days, St. Leger’s jägers, along with many of the Indians, engaged Stanwix’s defenders with an aimless exchange of fire. While St. Leger’s men maneuvered from tree to tree trying to find the best firing positions, the Americans improved their defenses by piling pieces of sod on the parapet. Other men from the command improved the road from Oswego in order to advance St. Leger’s heavy baggage and artillery, which would enable the British to conduct a proper siege.

Gansevoort and his command were in a tight spot, and he knew it. He had hope in the fact that many of his spies had reported back to General Schuyler to tell him Fort Stanwix was under siege. Schuyler was also receiving information about the strength of British forces. Most of this information came from a half-blood Oneida Indian, Thomas Spencer, who had watched St. Leger’s men march from Oswego. Spencer’s intelligence prompted Schuyler to order a relief force that would break the enemy siege on Fort Stanwix.

Having alerted many militia commanders in the region to the danger of an enemy offensive, Schuyler sent word of the siege to General Nicholas Herkimer, who commanded four Tryon County militia regiments. The threat of a British invasion had spread fear throughout the Mohawk Valley. General Herkimer wrote and distributed a rousing declaration requesting “every male person, being in health, from 16 to 60 years of age, to repair immediately, with arms and accoutrements, to the place to be appointed in my orders.” To that he added that the force would “march to oppose the enemy with vigor, as true patriots, for the just defense of their country.”

With enemy forces so near, it did not take long for Herkimer to gather the 800 men under his command. By August 3, he had his brigade assembled at Fort Dayton, some 40 miles east of Fort Stanwix.

Herkimer’s brigade was organized into four battalions: Colonel Ebenezer Cox commanded the 1st Battalion, from the Canajoharie region; Colonel Jacob Klock commanded the 2nd Battalion, from the Palatine region; Colonel Frederick Visscher commanded the 3rd Battalion, from the Mohawk region; and Colonel Peter Bellinger commanded the 4th Battalion, from the Kingsland-German Flatts region. (Tryon County at the time comprised a great deal of western New York. Today it is much reduced and called Montgomery County after the American general who died at Quebec in 1775.)

Thinking it was in Fort Stanwix’s best interest if he proceeded quickly, Herkimer prepared his men to march the next day. For speed, he decided to leave the bulk of his supply train at a prearranged depot and continue on with only a fraction of his ammunition and food.

In high spirits, Herkimer’s brigade marched west out of Fort Dayton on the 4th. After a march of 12 miles, the militiamen camped for the night at Starring Creek. The next day the patriots crossed to the south side of the Mohawk River and on the night of the 5th made camp between the Sauquoit and Oriskany Creeks.

During this day’s march, Herkimer sent his three best scouts ahead to Fort Stanwix with a message for Colonel Gansevoort, requesting that Gansevoort dispatch a sizeable force from the fort to meet Herkimer’s column. Herkimer believed that the combined American forces would then be able to break St. Leger’s siege. At the same time, Herkimer’s written message proposed that if Gansevoort was able to send out a force to meet his column, he was to signal with three cannon shots in rapid order.

“General Herkimer Is on His March to Our Relief”

About this same time, St. Leger found out about the relief column from a Mohawk scout who had spied it and run back to report. The British commander quickly instructed Butler to take his Rangers, Sir John Johnson his Royal Greens, and Joseph Brant at least half his Indians and lie in wait for the American militia, then to destroy them before they had a chance to reach the fort. The troops stole out of camp under cover of darkness.

Their departure, however, was suspected. An hour after Herkimer’s messengers arrived at the fort, Lt. Col. Marinus Willett addressed the men of the garrison: “Soldiers, you have heard that General Herkimer is on his march to our relief. The commanding officer feels satisfied that the Tories and the Queen’s Rangers have stolen off in the night with Brant and his Mohawks to meet him. The camp of Sir John Johnson is therefore weakened. As many of you as feel willing to follow me in an attack upon it, and not afraid to die for liberty, will shoulder your arms, and step out one pace to the front.” Willett collected over 200 volunteers.

Then, with the fort’s artillery firing grape-shot, Willett and his men succeeded in dispersing a large number of St. Leger’s men, capturing their colors as well as a substantial quantity of supplies. They took everything they could get their hands on, including food, cooking utensils, blankets, weapons, and ammunition. Willett ordered it all to be quickly loaded into wagons and, before the British regulars could cut off their route, the men withdrew to the fort with their loot, not having lost a single man.

Meanwhile, in the American camp at the fork of the Sauquoit and Oriskany, General Herkimer’s earlier mood for haste had turned to one of caution. After sending Gansevoort the request for an escort, Herkimer decided to discontinue the march. Then, having heard the firing of Willett’s raid, Herkimer was convinced reinforcements from Stanwix would arrive at any time. What he did not know was that Willett’s force never traveled, nor intended to travel, more than a mile from the fort.

During the night, many of Herkimer’s junior officers and a number of his battalion commanders met to discuss the column’s slow rate of march. By dawn, the night’s deliberations had fired many of the men’s tempers. Two of the angriest were Colonel Cox and Major Isaac Paris, an officer in Klock’s battalion.

In the early morning light, Cox and Paris approached General Herkimer and strongly insisted that the column move ahead at once and not wait for any “damned signal” from the fort. Calling a council of war, Herkimer explained that sometimes commanders must show “restraint,” and he believed that now was one of those times. Colonel Bellinger, Herkimer’s brother-in-law, supported this belief. Colonels Klock and Visscher remained silent.

As the meeting continued, Cox began to question Herkimer’s loyalty to the patriotic cause, while slandering Herkimer’s brother, who was a Tory. Cox then announced loudly, “I will not wait for a coward.” With that, General Herkimer walked to his horse, drew his sword, pointed it to the west, and shouted, “Vorwärts!” Echoing shouts of “Forward!” sounded throughout the camp. The militia immediately began to break camp and prepare for the march that was expected to take them to the walls of Fort Stanwix later in the day.

The road Herkimer had been traveling was an old corduroy that followed the rugged contour along the Mohawk River. Deep, heavily wooded ravines along the route held a number of small streams and marshy areas that slowly drained into the river. As the Loyalists and Indians prepared for battle, they soon learned that the terrain was perfect for an ambush.

Butler and Johnson decided to deploy their men along both sides of the road on the west end of the ambush. Brant’s Indian force, which was made up mainly of Seneca and Mohawk warriors, was positioned along both sides of the road, but also stretched eastward as far as their numbers allowed. The steep ravines with their dense, darkened forest served to conceal the 700 Loyalists and Indians very well.

To the east, only a few miles away, Herkimer prepared his militia brigade to march. He positioned Colonel Cox’s battalion in the front of the column followed by the battalions of Klock and Bellinger. Separating Colonel Visscher from Bellinger were the brigade’s supplies loaded on ox carts. About 50 Oneida Indians were deployed as scouts and flankers for the militia.

Once Herkimer’s column was on the road and moving, it stretched over a half-mile. With first light, the heat and humidity rose rapidly, but it did not depress the high spirits of the men now that they were again in motion.

With the Oneidas out in front and on the flanks, the men of the brigade felt secure as they moved closer to their objective. No one noticed the Iroquois warrior who lay hidden in the dense brush watching the militia march by. After he had counted most of the men in the column, he ran back and reported to Butler, Johnson, and Brant. The news was bittersweet. It was good to hear that Herkimer’s force was smaller than had been anticipated, but learning of Herkimer’s Oneida scouts did not ease anyone’s nerves. Nevertheless, the 700 armed men made final preparations before settling into their ambush positions. It was not long before they began to detect movement from the east along the King’s Highway.

From his hidden position, Chief Brant watched as Herkimer’s vanguard began to approach in singles and pairs. As the minutes ticked by, Brant watched Cox, Klock, and Bellinger lead their battalions over the ridges and into the ambush. The real prize, which was Herkimer’s supply wagons, rolled into view. Brant knew that the trap would be complete when Herkimer’s last battalion (Visscher’s) came into range. Before that could happen, firing broke out at the head of the column.

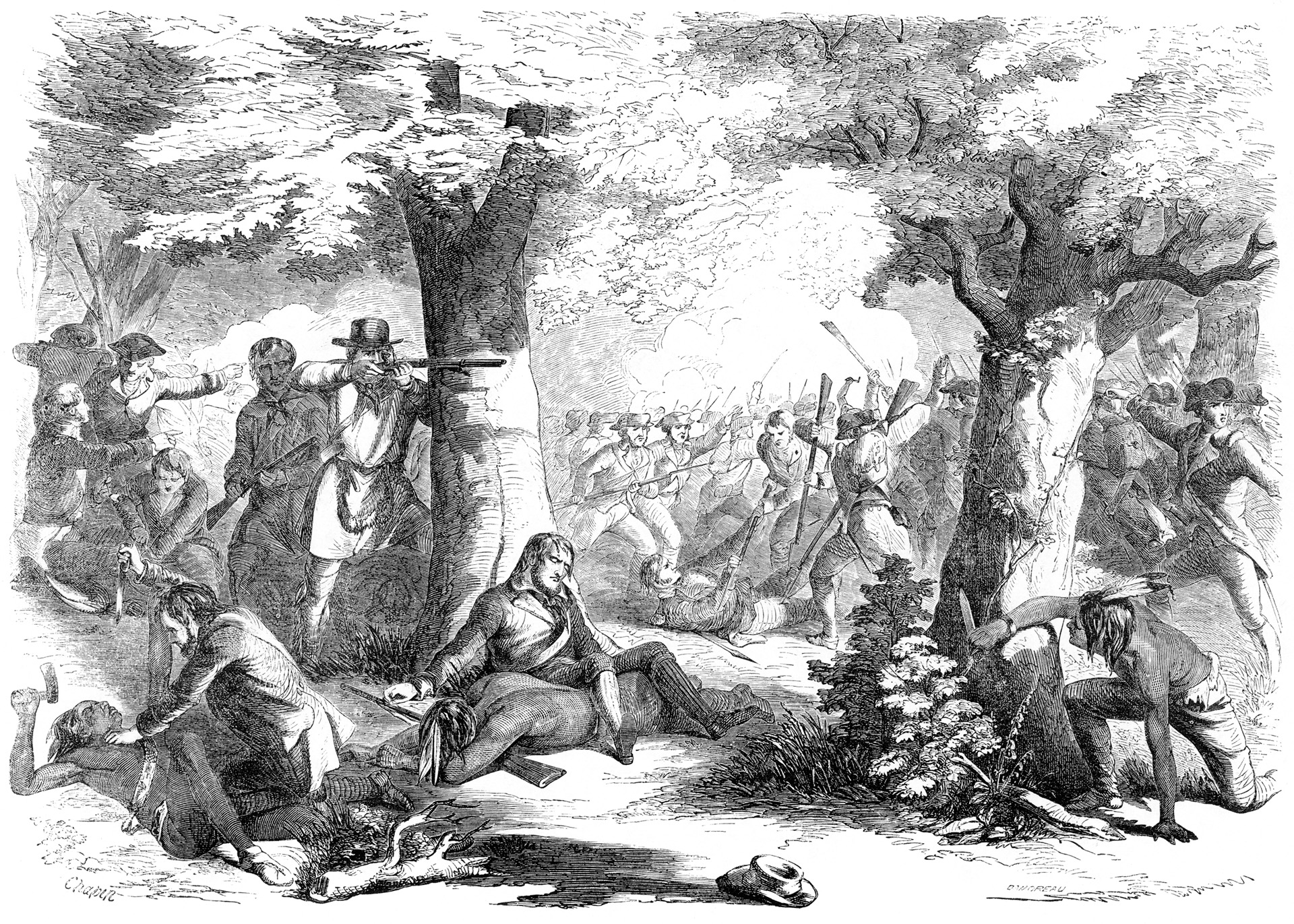

For some reason, the Oneida scouts had failed to detect the presence of the enemy. When the 20 men of the vanguard entered the ravine at the head of the ambush, they stopped, put down their weapons, and began drinking from the stream that ran under the road. They were unaware that only a few yards away dozens of Iroquois warriors were watching them. Waiting for Brant’s signal to attack was impossible for the undisciplined warriors, who could not resist the tempting target of the vulnerable militia spread before them. Standing together, the Iroquois fired at the reclining men and then charged the helpless, startled group.

Within seconds, the slaughter was over. Nineteen of the 20 men who had stopped to refresh themselves were shot, speared, or clubbed to death. Not satisfied, the victorious warriors headed down the road toward Colonel Cox’s 1st Battalion. Realizing the trap had been sprung, Butler’s Rangers and many of the remaining Indians began firing on the three battalions inside the trap. Only Visscher’s 3rd Battalion remained outside the initial killing zone of the ambush.

Brant, with a splinter group of 80 warriors at the far eastern end of the ambush, decided to remain hidden. He wanted to see how the battle progressed before committing his force.

Colonel Cox Killed Instantly by Musket Ball

With the sound of shots up and down his line, Herkimer sent orders to Colonel Cox to form his battalion in firing lines to meet the attack coming down the road. On horseback, Cox began shouting orders when a musket ball shattered his head, killing him instantly. Because many of the militia officers remained on horseback early in the ambush, several were killed in the initial attack, making it difficult for the militia to form an organized defense.

Major Samuel Campbell and Captain Jacob Seeber formed the 1st Battalion into a line of battle just in time to meet the reckless frontal attack coming down the road. The Indian attack was led by newly appointed Seneca chiefs such as Axe Carrier (Hasquesahah), Things on the Stump (Dahwahdeho), and Black Feather Tail (Gahnahage). As the bold warriors quickly approached their front, the 1st Battalion fired a volley that cut down over half their number. Shattered, the Indians withdrew, the survivors being instructed by the old chiefs to snipe at the militia from behind cover rather than attempt any more attacks across open ground. In fact, the elder chieftains explained that for the remainder of the battle, the warriors were to wait for the enemy to discharge their muskets and then charge while the men were reloading.

As enemy firing increased, Herkimer sent word to Klock and Bellinger to bring their battalions forward to support the 1st Battalion, but could not get word to Visscher. The reason was penned at a later date by Colonel Butler: “The first deliberate volley that burst upon them [the militia] from a distance of a very few yards was terribly destructive. Elated by the sight, and maddened by the smell of blood and gunpowder, many of the Indians rushed from their coverts to complete the victory with spear and hatchet. The rearguard promptly ran away in a wild panic.”

The panic had set in when Klock’s adjutant, Anthony Van Vechten, lost his nerve in the heat of battle. As he ran back along the road he began yelling, “Run, boys, run, or we shall all be killed.” Many men who were already intimidated by the swift, violent attack needed no further prompting. Within minutes, most of Visscher’s battalion was running to the east. Although Colonel Visscher rallied some of his men, who were able to fight their way west through the enemy mass to join Herkimer’s main force, most of the 3rd Battalion was cut off.

Viewing the panic, terror, and confusion from his elevated position above the battle, Chief Brant knew this was the moment to strike. Soon his men were chasing down, shooting, and clubbing the militiamen as they tried to run and hide. Colonel Visscher tried to reestablish contact with his broken battalion, but there were too many enemy warriors to allow him to rejoin his doomed command. Unfortunately, along with the destruction of the majority of Visscher’s 3rd Battalion, the column’s supply wagons were also captured by Brant’s Indians.

Slowly, the American militia began forming into tight circles and fighting back. At the same time, Herkimer ordered the men to start moving toward higher ground away from the bloody ravine where many of their own were still being killed. He also ordered them to team up with partners. He told the men to have one man fire while his teammate watched for an enemy who might charge what he thought was a defenseless man reloading his weapon. Herkimer had grasped the tactics of his enemy in quick fashion.

Although Herkimer had moved his men off the road and into the woods, his defensive perimeter shrank owing to the brigade’s heavy losses. As the enemy’s superior numbers began to press in on the militia from all sides, they searched for weak spots in the brigade’s line. But with less ground to defend, Herkimer’s perimeter became stronger as the men massed their fire together. In many places around the defensive position, the fighting became close, with men shooting, stabbing, and clubbing each other in small, violent, individual skirmishes.

The firing on both sides became so intense that for a mile along the road the thick growth of trees become “perforated” to a height of 20 feet from the volume of musket balls. To many of the men, the forest “had the appearance of a building lately battered by a hailstorm.”

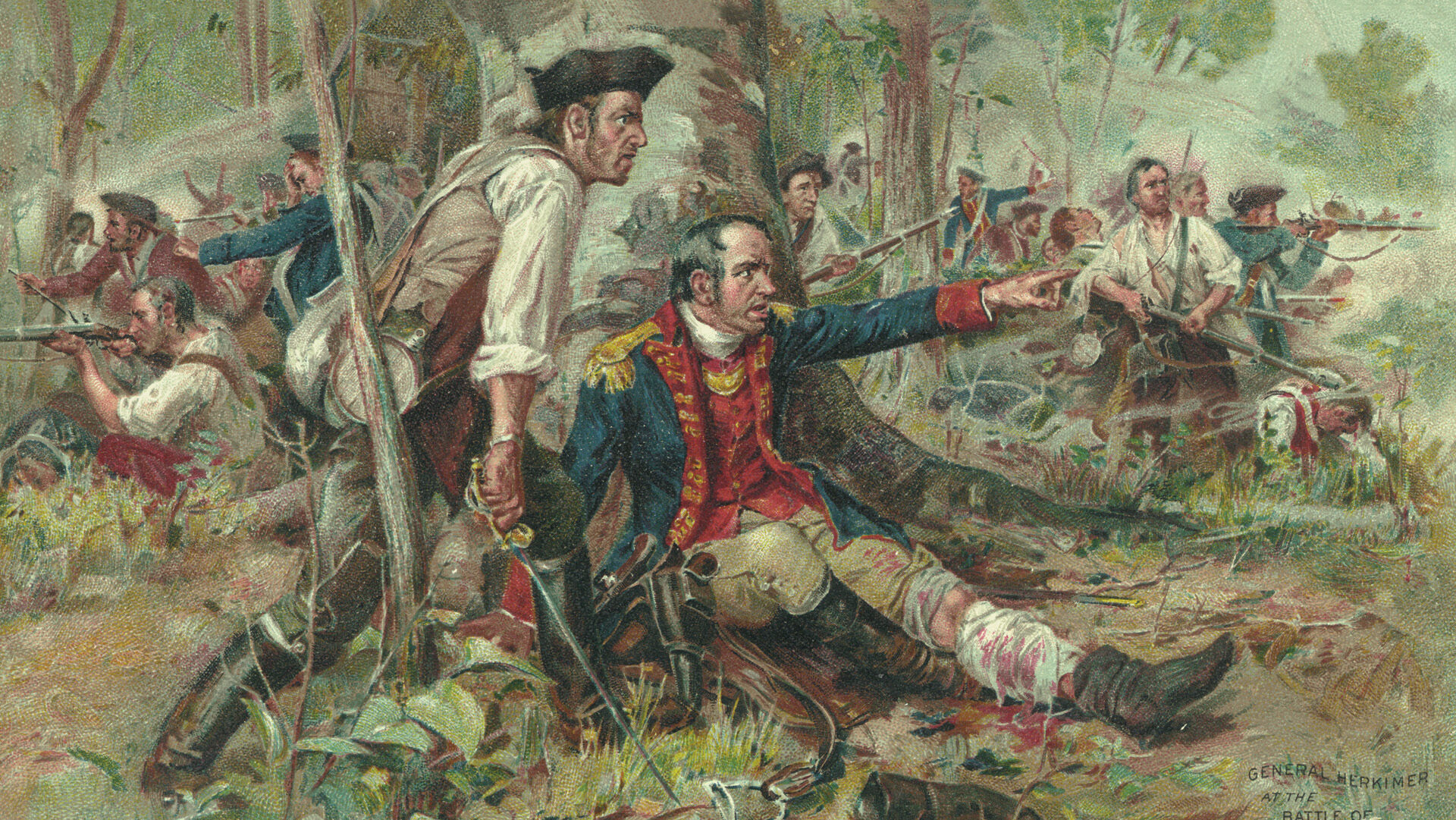

Just when Herkimer was getting a grasp on the tactical situation inside his line, a musket ball shattered his leg below the knee and passed into his horse, killing it. Immediately, many of his men, including Captain Christopher Fox, scrambled to the general’s aid. He was helped out from under his dead mount, moved to a nearby tree, and propped up against the saddle, which had been removed from his horse.

Moses Younglove, the brigade’s surgeon, dressed Herkimer’s wound. The general knew that his men were watching, worried that he was too injured to continue the battle. So Herkimer kept shouting orders and encouragement to his command. Following repeated requests from many of his officers to retire to a safer place, the general replied, “I will face the enemy.” The men were proud of their general for carrying on, and Herkimer was just as proud of them. Having been assaulted on all sides in attacks that had killed many of their officers, the undisciplined militia was fighting back remarkably well.

Herkimer’s resolve strengthened his men’s will to fight. His militia, as they came to hand-to-hand melees with swords, knives, and clubbed muskets, fought as a single determined unit. The Oneidas also fought courageously. Many warriors had their families along with them, and during the battle many wives and children fought next to their husbands and fathers. Allan Foote wrote in Liberty March: The Battle of Oriskany that the Oneida warriors were a devoted and trustworthy force that proved them to be “America’s first ally in war.”

At about 11 am, a tremendous thunderstorm swept across the battlefield. Lightning flashes mixed with thunder and torrential rain slowed much of the fighting in and around the ravine. The main concern on both sides was trying to keep the powder supply dry. The American officers and sergeants who were still able to command tried to take advantage of the lull in the fight to more effectively reposition their men inside the perimeter.

At one point during the storm, the men of the brigade let out a cheer when they believed Fort Stanwix’s guns had fired, signaling that a rescue column from the fort was on the way. What the men thought was cannon fire turned out to be thunder sounding through the hills.

During the hour-long downpour, while the men tried to shelter themselves as best they could, many of Brant’s warriors died making wild charges, believing the militia could not fire due to wet powder. Again the ill-trained militia demonstrated that they were a force to be reckoned with on this summer’s day.

As suddenly as the storm began, it ended. In most places around the perimeter, the fight resumed with intensity. Thinking it was time for his men to join the fight, Sir John Johnson formed his Loyalist Royal Greens into battle line for an advance against the militia. He hoped for revenge against the men who had forced them into exile from the Mohawk Valley earlier in the war. The men of the Tryon County Militia, seeing the green-jacketed Loyalists forming to their front, wanted to punish them again for abandoning the patriotic cause.

Americans Buoyed by Signal from Fort Stanwix

The militia, taking aim at Johnson’s ranks, fired one volley and then, rather than reloading, attacked the enemy with a frontal assault. Rushing out to meet the Loyalists, the militia used their bayonets, knives, and muskets to club and slash Johnson’s men in a wild 30-minute fight. By 1 pm, as the melee was winding down, guns from the fort were heard through the forest—the hoped-for signal from Gansevoort! The men in the perimeter took heart.

Although Stanwix’s guns buoyed American spirits, they also sparked in St. Leger’s force a diabolical plan. Colonel Butler thought that if the enemy was expecting reinforcements, he would falsely provide them. Placing Major Stephen Watts, brother-in-law of Sir John Johnson, in charge of a formation of Royal Greens, Butler ordered the men to turn their jackets inside out. Butler and Watts believed that if this oddly dressed formation could get close enough to Herkimer’s lines before being identified as the enemy, they would be able to penetrate the Americans’ defensives long enough for Brant’s Indians to assault through the break in the lines and decisively defeat the militia.

Organizing themselves into marching formation, the Loyalists began moving toward the militia. As they came into view, many of Herkimer’s men let out a cheer, thinking they were seeing reinforcements from Stanwix. Indeed, one of the militiamen rushed forward to welcome his “friend” at the head of the column. This unfortunate man was immediately taken prisoner.

Witnessing what had just happened, Captain Jacob Gardenier ran forward and liberated the prisoner while wounding and killing several Loyalists. In the struggle, Gardenier received bayonet wounds in both thighs as well as a severe wound in his hand. During the fight some of Gardenier’s men shouted, “For God’s sake, captain, you are killing your own men!” Calling back, Gardenier replied, “They are not our men—they are the enemy! Fire away!”

Only a handful of men fired. Many were not convinced the troops to their front were Loyalists. It was not until Captain Gardenier was helped back inside the lines that a full volley was fired in which 30 Loyalists fell.

This volley sparked the most savage portion of the battle. With total disregard for their well-being, the American militia rushed out and savagely assaulted their ambushers with a fierceness rarely displayed in the Revolution. These bloodthirsty attacks were met with equal ferocity from the British side. At times, weapons were thrown to the ground, and the men went at one another with their bare hands, punching and choking each other to death. The brutality continued until news reached Brant’s Indians that a sortie of some 250 men from the fort—Willett’s raid of the night before—had ransacked their camp. The Indians were incensed and decided to return to their camp.

Butler and Johnson pleaded with Chief Brant to stay and continue the fight with his men. Never having wanted to fight a conventional battle in the first place—which was what the ambush had become—Brant encouraged his warriors to quietly withdraw. With the Iroquois call for retreat, “Oonah! Oonah!” filtering through the forest, the Indians withdrew toward their plundered camps. An eerie silence then settled over the ravine.

With Brant pulling away from the battle, Butler and Johnson realized that their Loyalists were outnumbered. The two commanders had no choice but to retire as well. At roughly 3 pm, five hours after it had begun, the battle ended.

When the enemy had completely departed the battlefield, the Tryon County Militia began to search for their wounded. Fearing that the enemy might return at any minute, the men decided to leave their dead comrades where they had fallen. They retreated in the direction from which they had come, with none marching on to Fort Stanwix.

General Herkimer was taken by wagon and then boat to his home on the south bank of the Mohawk River near Little Falls. Because both of the brigade’s surgeons had either been wounded or captured, an inexperienced surgeon was assigned to care for the general. The surgeon amputated the leg, but could not properly attend to the arteries afterward, and so one of the Revolution’s greatest heroes slowly bled to death. Later, Congress authorized a monument to be built in General Herkimer’s honor. Also named in his honor are the county of Herkimer and its seat, the town of Herkimer several miles west of Little Falls.

At Fort Stanwix, St. Leger’s siege slowly dissolved. Chief Brant and his warriors, not accustomed to fighting pitched battles for hours at a time, were demoralized. Making matters worse was the knowledge that General Benedict Arnold was on his way with a large force to relieve the fort. Then, in a crowning blow for St. Leger, the Indians rioted in camp, stealing clothing and other personal items from St. Leger’s regulars before leaving with Brant. Having lost his strong Indian contingent, St. Leger had little choice but to abandon the siege and withdraw to Oswego.

Who Was Victorious at Oriskany?

Tactically, it is difficult to determine who was victorious at Oriskany. On one hand, the Loyalists and Indians prevented Herkimer from reaching Fort Stanwix, while on the other, the New York militia exacted a heavy toll on their enemy and forced them from the battlefield.

Without a doubt, the Battle of Oriskany contributed to a campaign victory for the Americans. St. Leger was forced to end his siege of Fort Stanwix and, at the same time, was prevented from accomplishing his primary objective, that of attacking Albany from the west. The fact that St. Leger could not complete his mission in no small way aided the American forces defending Albany. As a result, Burgoyne had difficulty protecting his line of communication while facing strong and well-led American forces. He was blocked by them at Saratoga and, after the Battle of Freeman’s Farm in September and the Battle of Bemis Heights in October, surrendered his entire army.

The American victory at Saratoga was a keystone in the drive for Independence, and the action at Oriskany had played an important role. For one, Chief Brant was anguished by the huge loss of his warriors. This eventually drove a wedge between him and the British, thus eliminating strong cooperation between the two groups for the remainder of the war.

More critically, America secured an exceptionally strong ally when France, after learning of the victory at Saratoga, decided that the patriots were worth backing. If General Washington could keep his Continental Army in the field over an extended period of time, and if French sea power could be brought to bear, then the American chances looked good.

However great the patriot victory at Oriskany, the Tryon County Militia Brigade was nearly destroyed. Almost 60 percent of the brigade’s men were killed, wounded, or captured. Hardly a family in the entire county was left untouched. The grief felt by the people over the loss of a father, son, husband, or brother consumed the entire region for years. With approximately 450 men from the county lost as well as another 200 Loyalist and Indian casualties, the Battle of Oriskany is noted as one of the bloodiest for its size in American history.

On North Lake Road is a NYS history sign that says this road was used by 450 of St. Leger’s Indian allies in their retreat to Crown Point. Is there any record of what route they followed from North Lake Rd to Crown Point?

Am I correct assuming these were Mohawks? Mad and disappointed with the British why did they go to Crown Point? Maybe they had nowhere else to go. The Brits had re-occupied Crown Pt the year before but left only a small garrison plus the village by the ruined fort.

Thanks,

BillC

Have spent some time in the Rome-Utica area, remember seeing signs for the town of Herkimer. The US Navy carrier Oriskany was named for this battle.