By Leo G. Barron

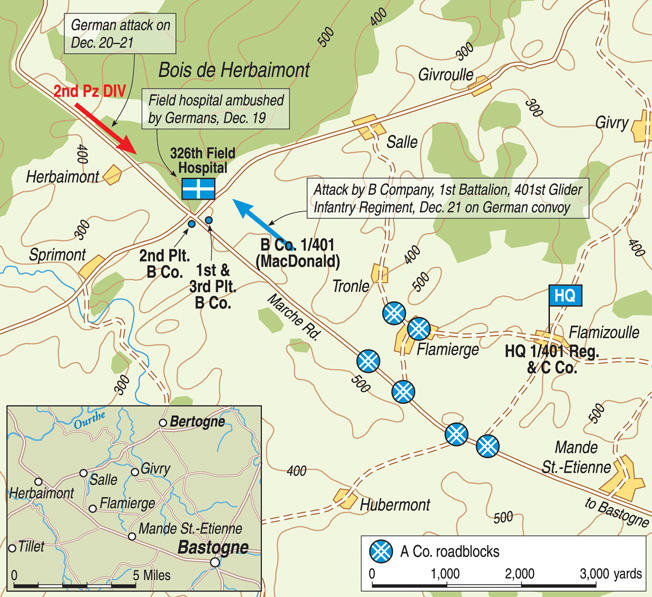

For the cold and hungry GIs of Company B, 1/401st Glider Infantry Regiment, holding the western approach to Bastogne would push the men to the limits of their endurance. During several frigid days in December 1944, the young glider fighters of the 101st Airborne Division fought over a bleak intersection outside the Belgian town. The intersection, nicknamed Crossroads X by the men, quickly became the focus of bloody struggle between the Americans and Germans, as the might of Adolf Hitler’s armored forces desperately sought a way into besieged Bastogne.

Private First Class Carmen Gisi of B Company remembers the contested landscape as if it was yesterday. “After the battle at the Crossroads we found out that we were fighting the first elements of the Germans’ 2nd Panzer Division,” Gisi recalled years later. “We were told we held up the offensive for two days, which was very critical to the Germans.”

Due to the stubborn actions of Gisi’s single company, the might of the 2nd Panzer Division would be stymied in its attempts to break into Bastogne’s “back door” during the early days of the famous siege. The contest for Crossroads X would become brutal and desperate as seasoned Americans faced German armor. In the bigger picture, the valiant holding action by B Company would help put an end to Hitler’s last great offensive in the West, the Battle of the Bulge.

Arriving in the Wake of Bad News

When the glidermen of Company B, 1/401st Glider Infantry leaped from the tailgates of the trucks that brought them to the outskirts of Bastogne on the night of the 19th, many of them had no clue where they were. The hours spent in the exposed trucks had been cold and miserable, and the men were happy the trip had come to an end. Initially, Lt. Col. Ray Allen, the commander of 1/401st Glider Infantry, ordered his companies to take up positions straddling the Marche Road and to prepare to defend the ground past the town of Mande St. Etienne. This location would help protect the road and was closest to the original assembly area, which grew increasingly quiet that night as the last groups of Screaming Eagles marched off to their positions.

Bad news had arrived earlier that evening. The division’s 326th Medical Company had set up a field hospital in an open area to the west of Crossroads X (the intersection of the Marche Road and the Barriere Hinck). It was the 101st’s farthest position west of Bastogne. Almost as soon as they had pitched their tents, the hospital crew, believing they were in a safe rear area, had been attacked by advance elements of the 2nd Panzer Division. Rumors quickly reached the high command that the hospital had been wiped out. In the Heinz barracks headquarters back in Bastogne, the acting division commander, Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe, looked visibly shaken when he heard the news, even if the particulars were unknown at the time. Not only would the division now find itself woefully short of corpsmen, medical officers, and supplies, but McAuliffe was concerned that the Germans had managed to get behind the growing American defensive perimeter so quickly.

The news of the attack was a wake-up call for McAuliffe. He now realized how fast the Germans were moving. He needed to move immediately to regain control of the situation and secure the rear of his defenses around Bastogne.

The Young Captain Robert J. MacDonald

The man leading the mission to recapture the vital crossroads was Captain Robert J. MacDonald, the no-nonsense commander of Baker Company, 1/401st Glider Infantry Regiment. Like many World War II commanders, MacDonald was young. A reporter who knew MacDonald described him: “When young MacDonald stood up straight, he towered over his battalion commander like a beanpole: six feet, three inches tall; soaking-wet weight, 145 pounds. His flesh was so sparse that his shoulders were rubbed raw by the strap when he carried a pack. Only 23 years old, MacDonald had learned his lessons well in combat in Normandy and Holland.”

That night, MacDonald received a warning order around 2230 hours. Shortly afterward, the patrol, led by MacDonald himself, crossed the line of departure and headed west. MacDonald recalled how his company had ambushed a German infantry column marching down a road in Holland several months earlier. He vividly remembered how exposed the Germans were when he ordered his machine guns to open fire. He ordered his men to approach stealthily in the foggy dark, keeping strict noise discipline. MacDonald also divided Baker into two columns. Sneaking through the ditches on either side, each group moved cautiously, purposely keeping off of the Bastogne-Marche Road. As the men approached the crossroads they could see the orange reflection of burning vehicles in the night sky. An even more troubling clue as to the fate of the hospital soon reached their ears.

MacDonald’s men heard the strangest of sounds. It was a loud, continuous wail. Gisi, the young gliderman from New Jersey, remembered how eerie and shrill the noise was in the damp night air. When the Americans climbed a ridge overlooking the crossroads, they viewed a scene of utter devastation.

Laid out in front of them were 16 burning 21/2-ton trucks. The vehicles had been abandoned by the roadside, still in convoy along the Salle-Barriere Hinck Road. A driver’s body had slumped forward in the cab of one of the trucks, lying on the horn and producing the wailing noise. Several bodies lay strewn about the fields near the hospital tents. MacDonald surveyed the scene and quickly began to formulate a plan. First, he sent two scouts down the slope to reconnoiter the area. The GIs crept stealthily away and after several minutes returned to report the Germans were still milling around the area. MacDonald breathed a heavy sigh. He knew Baker Company was about to go into battle again. This time, instead of the dikes and wet fields of Holland, it would be over a misty road junction in Belgium.

Germans at Crossroads X

As MacDonald and his men prepared to recapture the crossroads, the radio operators at the 327th Regimental Headquarters tracked their progress. As the reports came in, they scribbled messages on radio logs to keep their commanders informed. It had been a busy morning so far. One of the men taking notes belonged to Captain William L. Abernathy’s S2 section. For him, the news was not good. At 0045 hours, reports filtered in that the Germans had sent half-tracks mounting heavy machine guns to guard Crossroads X. In addition, the Germans supposedly had captured an American armored vehicle and were using it to defend the same crossroads.

Moreover, if there was any doubt about the fate of the medical company, the report at 0115 confirmed the Americans’ worst fears. A jeep driver had escaped and reached one of the security patrols on the perimeter. The lucky paratrooper was from the 326th Medical Company and reported that indeed the Germans had captured the entire company, including the wounded on litters. As the Germans herded the prisoners together, several of the machine gunners in an African American transport company opened fire with their heavy machine guns. Chaos ensued as men on both sides dove for cover. Bullets zipped and zinged everywhere, slaying friend and foe alike. Within a few moments however, the Germans killed the brave truckers, ending the fight.

During the ensuing chaos, the plucky jeep driver had escaped, frantically making his way back to American lines. The information he provided was quickly relayed to McAuliffe’s headquarters. According to the driver, close to 100 Germany infantrymen had occupied the crossroads. With them were two half-tracks and multiple small arms, which seemed to confirm the earlier report. According to other survivors of the attack, many of the Germans were wearing civilian clothes and American uniforms as a ruse. However, unlike the soldiers, the officers wore the standard German field uniforms. Survivors stated that the German unit had machine-gunned the tents and trucks, even though many were clearly marked with red crosses.

In short, the Germans were at Crossroads X in force. It began to look like Baker Company would have a major fight on their hands.

Carelessness of the Germans

Meanwhile, Gisi could not believe the Germans were being so loud and careless. As one of the pair of scouts that MacDonald had sent to the crossroads to investigate the situation, he and a comrade crouched on their knees just below the short incline to the road, hidden from the Germans by the dark. Cautiously, the two men had snuck up to the road, clutching their M1 Garand rifles, fingers hovering over the triggers.

“It was a miserable night. Dark. Snow flurries,” Gisi recalled. “Sergeant [Mike] Campana [Gisi’s platoon sergeant] instructed me and Charlie Sawyer to head out first, since we were scouts.”

Campana told Gisi and Sawyer to fire two shots, which would be the signal to commence the attack. The rest of the company would then come down firing in an extended line, parallel to the road. As Gisi waited, he still could not believe the Germans were so close and so blatantly violating the military doctrine of noise discipline.

“We could actually see them [the German soldiers] pretty well. Geez, even in the dark, I was 4-5 feet away, and Charlie and I were crouching on our knees behind that little rise there. We could hear them talking in German and their hobnails on their boots as they walked back and forth on the road.”

The Germans had let their guard down. They had not pushed out local security elements to ensure their area was safe. MacDonald’s glidermen were about to teach them a fatal lesson for their military indiscretions.

Direct-Fire-Death

MacDonald’s plan was similar to a double envelopment. He quickly gathered his platoon leaders and platoon sergeants and, like a kid outlining a complex play on a sandlot football field, explained his plan. On the northeast side, Campana’s 3rd Platoon would occupy a blocking position to prevent Germans from escaping down that road. On the southwest side, 1st Lt. Selvan E. Shields would establish another blocking position. Meanwhile, 1st Platoon, under 1st Lt. John T. O’Halloran, and weapons platoon, under Technical Sergeant Robert Dunnigan, would set up a support position in the middle, facing almost directly at Crossroads X. Awaiting the signal from the scouts, the officers and senior NCOs moved out to their platoons.

Lieutenant O’Halloran returned to his platoon and quickly briefed them on the operation. The glidermen of 1st Platoon moved out. When they were close to the objective, O’Halloran gave the order and the men lay down on their stomachs, as if to slither their way toward the burning trucks. While they waited for the signal, and though they were a little farther away than Gisi and Sawyer, the men of 1st Platoon could also hear the Germans chatting and laughing, oblivious to the impending attack.

To 1st Platoon’s right, 3rd Platoon edged forward into its attack position. It was at that moment that Gisi fired the two shots, splitting the night like thunder.

Suddenly, over 100 slivers of light shattered the darkness. The steady rat-tat-tat of M1919 machine guns and the heavy chugging sound of Browning Automatic Rifles echoed across the rolling fields. For the Germans trapped in the crossfire, it was direct-fire death. The Germans scattered in all directions like cockroaches. When 1st Platoon heard Gisi’s rifle shots, the men stood up and opened fire. While they were firing, they marched forward to the trucks like gunslingers in an old Western film. When they reached the burning vehicles, some of the men then tossed hand grenades into the wood line just beyond the crossroads to kill any retreating Germans. Meanwhile, some of the German soldiers tried to escape down the northern and southern roads only to find the Americans waiting for them. For many of those Germans, it was their last decision. For the Americans, it was easy pickings. Only a handful of Germans managed to escape westward on the road to Tenneville.

Retaking the Crossroads

Nearby, Gisi and Sawyer saw shadows rapidly approaching. The two men quickly aimed their M1s at the dark blobs. They called out to make sure the targets were German before they opened fire. The reply was in German. Campana’s platoon was still coming down from the ridge behind them, but Gisi knew they could not wait for them. They had to act now. As fast as they could squeeze their triggers, the two men shot round after round into the shadowy shapes.

Gisi remembered: “Those Germans were close. They came right in front of our company when we hit them. I know when we [he and Sawyer] fired we killed a few of them. We even threw some grenades, but it was a short fight.”

If any Germans had remained, Gisi felt sure the grenades had killed them. By the time the platoon reached the two scouts by the road, the fighting had ended. Gisi was thankful he had dodged death again. Fortunately, Baker Company suffered only one casualty. Gisi’s buddy, Frank Almovich, suffered a minor wound when a bullet grazed his left ear. Campana also had a close call when a German rifle round ricocheted off the buckle of his ammo belt. Other than that, Baker Company had successfully recaptured the crossroads intact.

Captain MacDonald instantly informed Allen that the crossroads was in American hands. It was now 0445 hours. Even in the dark, MacDonald could make out the wreckage that was once the hospital in the field beyond the road. His men cautiously approached the tents, searching for comrades. They found no survivors. Allen called back and ordered MacDonald to set up a battle position with his company to defend the crossroads from any subsequent German attacks. MacDonald acknowledged the order and went to work. He knew he was out on a limb, far from the rest of his battalion. He could only hope the Germans did not know how vulnerable his position truly was.

Assessing Damage, Scrounging for Supplies

As dawn broke on the morning of the 20th, MacDonald and his men continued to explore the crossroads. The dead were everywhere. To the relief of everyone present, someone finally pushed back the body of the dead driver from the wailing truck horn. According to Gisi, the only sound after that was the eerie crackling of the flames in the burning vehicles.

When he entered the abandoned field hospital, Gisi discovered two dead paratroopers. The Germans had slit their throats. One of the luckless paratroopers was still on a stretcher with his arm attached to a bag of blood plasma on a stand. Still, Gisi is not sure to this day that what he witnessed was the result of an execution. “I think the Germans did that because they were too badly injured—to put them out of their misery.”

Gisi began to rummage through the wreckage and debris left behind. Reaching down in a hastily dug foxhole, he found a camera that still had some film. He turned around and snapped a photo of the abandoned field hospital. The empty tents, flapping in the breeze, were a reminder that the fortunes of war could turn on anyone at any time. The medics working in the hospital probably thought they were well behind friendly lines and protected from an enemy attack. Tragically, they were mistaken.

MacDonald’s company salvaged whatever supplies and equipment they could find, including ammo, gas, rations, and medical supplies. The biggest haul was two .50-caliber machine guns removed from the trucks. The glidermen were thrilled to have these pristine weapons that were still caked with the waxy Cosmoline from the original packaging. The heavy barreled machine guns would come in handy in the further fighting for Bastogne.

By 0800 hours, Captain MacDonald radioed Allen that his position was secured. Looking over his shoulder toward Bastogne, MacDonald could barely see where the next American unit was, even with the gradual rising of the fog and daylight. In fact, it was over 4,000 yards away near the town of Flamierge. Baker Company was an island. Despite this isolation, orders were orders. Allen had told him to defend the crossroads, and that was that. To make matters worse, MacDonald had no artillery support. A forward observer from the 333rd Artillery Group would show up later that day, but even he had no way to call back to division artillery. All MacDonald could do was hope the Germans did not press the issue and try to recapture the crossroads. If they did, Baker Company could end up like the field hospital.

Panthers on the Prowl

Later that morning, the ever-present fog rolled back in and blotted out the sun. MacDonald knew what that meant. The Allied fighter-bombers were not flying, and when the P-47s could not fly, the Wehrmacht would take advantage, moving its tanks out in the open. Sure enough, within a few minutes MacDonald and the rest of Baker Company could hear the clanking of metal tracks from the direction of the little town of Salle to the north. MacDonald’s GIs jumped into their foxholes and waited. Soon, they could see the steel monsters—two German Panther Mark V tanks from the 2nd Panzer Division. They were only 50 yards up the road from Crossroads X when they rolled to a stop.

With a great grinding of gears, the two metal leviathans turned and moved off the road. MacDonald probably swore to himself. Earlier, he had two tank destroyers from 3rd Platoon, Baker Company of the 705th under his command, but they had left not long after they had arrived, believing the glidermen had things under control. The tank destroyer commanders did not think any German armor was about. They were wrong.

There was a moment of nervous waiting on both sides, perhaps as the tankers were sizing up the situation from inside their steel hulls. Suddenly, the Panther crews opened up with machine-gun fire spraying the crossroads with bursts of 7.92mm bullets. Luckily, because they were firing blind, the bursts went over the heads of the glidermen hunkered down in their foxholes.

MacDonald’s men were smart enough to realize this was more than they could handle without proper antitank support. No one shot back at the Panthers. With no reaction, the tank crews probably thought the Americans had left. The two tanks gunned their engines and headed back toward Salle. MacDonald and his men breathed a sigh of relief. Possibly, this had been some sort of armored reconnaissance, but they knew the Germans would return to push the issue. It was only a question of when.

Bastogne’s Early Morning Fog

On the 21st, Captain MacDonald awoke to another miserable, cloudy morning. This morning, the fog seemed to be at its worst, virtually surrounding his men. It seemed he would never see the sun again. Each day at Bastogne was like living in a London fog bank.

MacDonald knew that once again the fog meant there would be no air support. He shook his head. Logically, the Germans also realized it was another chance to try something against his position, probably with armor.

He looked outside his command post, watching some of his glidermen chomping on K rations while huddling in their foxholes, trying to stay warm and dry. Others were up and moving around, conducting their morning rituals. In their positions astride the Marche Road and on the heights above Crossroads X, it had been quiet for most of the morning. The only action so far had occurred when his forward observers detected some enemy tanks firing at them from northwest of the crossroads. In response, an observer requested a fire mission from the 463rd, which responded with a brief but apparently effective barrage. Other than that, the morning had passed uneventfully.

A Textbook Linear Ambush

Suddenly, explosions and gunfire tore through the stillness of the cold morning, as if a thunderstorm had burst among them. In his position to the right of the line, Sergeant Campana of 3rd Platoon heard the Germans vehicles before he saw them emerge from the mist. Without waiting for orders, he told his squad leaders to hold their fire. He wanted to know what was rolling down the road before firing on it. Even in the thick fog, Campana could tell that the vehicle sounds seemed to be coming from the town of Salle to the north, once again, most probably Germans.

The glidermen checked their weapons, making sure they were loaded and ready. As they waited in their foxholes and the vehicle noises increased, the anticipation began to build. MacDonald’s men could hear the humming of German engines. Finally, after waiting for a couple of interminable minutes, the vehicles emerged from the murky clouds like Viking ship prows in the Norse Sea. Lined up in a row were several German Kubelwagens and a truck. The truck was towing some type of artillery piece.

Luckily, 3rd Platoon had more than just machine guns and rifles. Campana had brought up one of the 57mm guns from the regiment’s Anti-Tank Weapons Company, and the crew quickly sighted the gun at the lead Kubelwagen. Campana gave the signal. Fire erupted along the entire line as the platoon targeted the lead car. The Kubelwagen exploded as round after round tore through its thin steel plating. As a result, the entire German column sputtered to a halt, but before they could back up, Campana’s men turned their attention on the trail vehicle. Within seconds, it, too, was a burning wreck.

Now, the entire column was trapped between the two destroyed vehicles. One Kubelwagen managed to weave its way through the maelstrom and escaped, frantically driving away at full speed. The others were not as fortunate. As the German soldiers jumped down from their vehicles, Campana’s riflemen blasted away at them. It was a textbook linear ambush. Deadly and sudden, within few short minutes it was over.

Carmen Gisi recalled what happened after the ambush. “Well, we went down to see what we’d hit. I think all of the Germans were killed. We killed about 50, I think. Several got away. I don’t recall any prisoners, no—I’m pretty sure they were all either killed or ran off. I remember searching this one officer, I’m sure he was SS—a tall guy. We found American cigarettes and candy that had been taken off our guys from the field hospital. That made us mad, you know.”

The 2nd Panzer Division

Hearing the action, Captain MacDonald rushed to the scene in time to witness the death throes of the German column as the last few vehicles were stopped by 57mm rounds. MacDonald nodded with grim satisfaction. His men had performed like the seasoned veterans that most of them were. They acted independently, like good troopers who did not rely on a call to their higher headquarters for orders and decisions. MacDonald was pleased that independent-minded NCOs like Mike Campana were the backbone of his company, and this morning they had shown their commander why Baker Company was one of the best in the regiment. After the firing died down, MacDonald called Colonel Allen to inform him of the good news. By 0900, regiment knew that Baker Company had destroyed an entire enemy column. It did not take long for Abernathy to determine the column belonged to the 2nd Panzer Division.

Several days before, the 2nd Panzer Division, part of the XXXXVII Panzer Corps, had burst through the Allied lines along the Our River as part of Hitler’s final offensive in the West. The division, commanded by Colonel Meinrad von Lauchert, was to execute the decisive operation for the Fifth Panzer Army. Its mission was to secure the crossings along the Meuse River near the city of Dinant.

For the first few days, the 2nd Panzer Division had tasted the fruits of victory. It had fought a bitter and tough battle to cross the Our River, but after it had penetrated the crumbling defenses of the 110th Infantry Regiment, it roared westward like an unleashed lion. Its next victim was elements of the 9th Armored Division near Hamiville on the 19th. After a brief but one-sided battle during which the 2nd Panzer Division destroyed over two dozen tanks from the 9th Armored, it pushed through the forces of Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division and the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Noville. To the Americans, it seemed no one could stop them.

Farther south, the Panzer Lehr Division, 2nd Panzer’s partner in the offensive, failed to capture Bastogne through a coup de main. The 101st Airborne Division had won the race to the town and secured the vital road hub. As a result, the supply lines of the 2nd Panzer Division had to circle around Bastogne from the north and then to the west. Overextended and vulnerable, this logjam created unforeseen problems, including increasing the amount of time it took vital supplies, such as gasoline and ammunition, to reach von Lauchert’s forward units. One such problem was the nondescript crossroads west of Bastogne, Crossroads X, where MacDonald and his men were stubbornly holding out, depriving the Germans of this vital road junction.

Preparing for the Next Attack

Baker Company’s action on December 21 had an important effect on the Germans. For von Lauchert, the ambush at Crossroads X forced his hand. He could no longer afford to ignore the American presence there since his forces and supply train were transiting so close to the nearby roadway. Now, he had to commit a Kampfgruppe, or battle group, to isolate and contain the American forces at Crossroads X, which he assumed to be a large task force. Had he known it was only a company, he might not have allocated so much combat power.

The Germans, however, could not take any chances. It was becoming essential that none of the American units in Bastogne be permitted to use the roads and push out, potentially recapturing the bridge crossing at the Our River, which would interfere with the German objectives to the west. In short, because of the aggressive actions of MacDonald’s men at the crossroads, the Germans believed the resistance meant a sizable U.S. unit was holding the area. The skirmishes at the intersection had grown from a nuisance to a serious threat to the German line of communication westward to the Meuse River.

For the Americans, it had been a job well done, even if they did not know how they had already disrupted the German plans for taking Bastogne and continuing to the Meuse River. For MacDonald’s men, however, their battle was just starting.

That afternoon, MacDonald’s 3rd Platoon continued to occupy its positions north of the highway looking west toward Marche. In front of them were the smoldering remains of the German column they had destroyed over an hour earlier. The glidermen were still pretty juiced up from the successful ambush, and it helped that it had been so one-sided. They had not lost a single man, but they had slaughtered scores of Germans. Regardless, many of the men guessed that the Germans were not going to give up so easily. Plenty of MacDonald’s men were veterans of Holland and Normandy. They had seen enough war to realize that their luck was probably not going to last. Fate could easily fall the other way.

MacDonald knew that anticipating the next German move could pay dividends yet again, saving the lives of soldiers and guaranteeing success for his small company. Early warning was one way to prevent an ambush. Therefore, he placed two bazooka teams forward of Campana’s 3rd Platoon and the crossroads. An hour after the Kubelwagen ambush, the bazooka teams bore fruit.

Panzer IVs vs Bazookas

Around 1230 hours, the bazooka men again heard the clanking of treads coming from the direction of Marche. Two tanks from 2nd Panzer were rapidly approaching, feeling their way up the road. Removing the safety pins, the American loaders slid the 2.36-inch rockets into each tube and wrapped the tiny wires from the back of the rockets into the magneto clamp on the back of each bazooka tube. They then patted the gunners on the back as a signal that they were loaded. The gunners readied themselves for action, fingers hovering over the large triggers. Private Joe Karpac was one of the gunners. He squinted, trying hard to peer into the misty gloom. Suddenly, he could make out two German Mark IV tanks heading straight down the road.

Long before, Karpac and the other team had worked out a system where they would draw the tank’s fire, and after the tank fired, shoot before the tank could reload. It was a risky system if the gunner had the guts to expose himself. This would be even riskier today, since Karpac noticed they had only a frontal shot, the place where a tank’s armor is thickest.

The gunners tensed as the metal beasts edged closer to their positions. Finally, the lead tank fired its main gun, shattering the silence. Karpac dashed into the road before the tank could get off a second shot. He had only seconds to look down the sight of his bazooka at the lead tank and pull the trigger. The M6 HEAT (High-Explosive, Anti-Tank) projectile whooshed from the barrel. Karpac could only watch helplessly as the round missed. Before the other enemy crew could get a bead on Karpac, he dove for cover.

With a great blast, the trailing tank shot its main gun at the elusive bazooka gunner. Now, it was the second bazooka gunner’s turn. Like Karpac, he jumped out to engage the tank, and like Karpac, he missed. Again, the trailing tank blasted its gun at Karpac’s comrades, but it missed too.

Amazingly, Karpac summoned up the courage to try this little stunt again. He felt confident he would not miss a second time. After the second tank had fired, he dashed back into the street. His heart was beating faster than a snare drummer on parade. Karpac took a deep breath to steady it. He peered down the tube sight again. The tank seemed to grow in his sights like some great charging beast. Finally, he pulled the trigger. In less than a second, the rocket sailed over the road and slammed into the German tank, which began to shudder and stall. Thick, oily smoke rose up from within it like a sputtering stove.

The effect was contagious. The crew of the other tank retreated. Shifting to reverse, the German driver began to back away from the surviving vehicle. The tank left the smoking wreck to its fate, clanking off to where it had emerged out of the fog.

Once again, MacDonald’s glidermen had successfully defended the crossroads. The men took a break, smoked cigarettes, congratulated each other, and breathed a sigh of relief. They knew it would probably be only a brief pause before the next German attack.

Baker Company in Peril

While Karpac and company were chasing off tanks near Crossroads X, their battalion commander, Lt. Col. Ray Allen, sensed it was time to rethink his plan. Baker Company’s little combat outpost had certainly disrupted Wehrmacht movements around the crossroads as well as holding off multiple enemy probes over the last 24 hours, but it was isolated and dangerously exposed. The crossroads was getting harder and harder to defend. Allen knew that if the Germans decided to press their numbers, they would easily overwhelm MacDonald’s tiny force.

As the morning drew to a close and he received the reports, Allen was becoming more convinced it was time to bring back MacDonald and his boys. At 1130 hours another straggler from the 28th Infantry Division arrived at the command post. He was tired, haggard, and sullen. Still, he provided some valuable but troubling information to Allen: the Germans were in Sibret. In fact, the straggler said he had seen two tanks and 30 Germans there. If that was the case, it meant the Germans had finally cut the road to Neufchateau and Bastogne truly was surrounded.

The news became worse in the afternoon. One of Allen’s own patrols reported back at 1220 that the Germans had occupied the town of Chenogne with 30 soldiers. According to Allen’s map, Chenogne was a mere 11/2 miles northwest of Sibret, and Sibret was only three miles from his own CP near the town of Flamierge. He gritted his teeth. If he did not pull Baker Company back soon, the Germans would likely come up from the south and cut off MacDonald’s men. If that happened, Allen would be unable to do anything to support or rescue the lone company. After all, his other two companies, Able and Charlie, were having troubles of their own. Both were busy defending other parts of the sector.

As a matter of fact, the entire battalion was out on a limb with only a thin stream of supply and communication to Allen’s headquarters. Allen knew that division headquarters wanted them out there, and no other orders had come down from Harper or anyone higher to relinquish the crossroads and pull B Company back. The whole situation was making Allen anxious. He knew that with each passing hour, as the Germans continued to move through the fog banks groping to find gaps or the flanks of the his lines, the situation for MacDonald and his men grew more and more precarious.

Withdrawing from Crossroads X

By midafternoon, Baker Company’s situation was beginning to deteriorate. MacDonald’s stubborn glidermen had not suffered any significant losses, but the Germans were pushing hard on three sides, and it was merely a matter of time before they broke through the lines somewhere around the 1/401st salient. Since Baker was the most extended company, Allen felt it was the one unit most in peril at the time. This was confirmed at 1350 when Allen heard the radio crackle as MacDonald reported that they were under attack again. It was the third push the Germans had attempted that day.

Allen made sure his command post forwarded every report to regiment as quickly as possible. He knew that Harper’s regimental headquarters would pass this information along to division headquarters. McAuliffe had left Allen the discretion to withdraw when he felt his battalion was in danger of being cut off. Pulling B Company back a bit would help him consolidate his already thin line of defense around Mande and Flamierge.

Welcome news finally arrived that afternoon. McAuliffe had discussed the situation with his staff, and after careful consideration McAuliffe had agreed to withdraw Baker Company from Crossroads X. The signal was coded and sent to Allen. Almost immediately, and with a certain measure of relief, Allen had his radio operator instruct MacDonald to pull back in the manner prescribed. Allen then looked at his watch. It was now 1400 hours. He hoped that it was not too late.

Several hours later, Captain MacDonald stomped the mud off his boots as he entered the battalion headquarters to report that his company had safely returned from Crossroads X. Thankfully, the company’s withdrawal went smoothly. The men had commandeered some of the trucks from the abandoned field hospital and used the vehicles to transport the company and its support elements almost three miles back to friendly lines. As a result, the whole process took very little time to complete. Within a half hour the men of Baker Company were digging in on a new line of defense near the town of Flamizoulle.

Crossroads X: A Tiny Version of Bastogne

Still, MacDonald was fuming. He realized how shaky his position had truly been. He felt his entire company had been fighting off Germans with little support from the rest of the battalion, much less the division. Frankly, he had no idea why he was out there hanging onto the crossroads by his fingernails. Any commander knows that it is hard to get his men to fight for something when he, himself, could not see the purpose behind their mission. MacDonald, who by nature was a bit volatile, struggled to control his anger and frustration when he went to see Allen.

Several years after the war, MacDonald recalled his feelings that night: “From a company commander’s position up to this point I frankly could see no sane reason for our having been out on the mission that we had just completed for such an extended period of time. This is a dangerous state of mind for any commander to be in.”

Allen could see that his subordinate was angry. In a fatherly fashion, Allen immediately calmed his company commander. “It’s good to see you back, Robert. You probably wondered why you were out there for so long,” Allen said, shaking MacDonald’s hand.

MacDonald nodded and replied, “As a matter of fact, sir, I did wonder why we were out there for so long.”

“I realize you were out there with no one on your flanks. However, your little outpost really disrupted the German panzer division trying to sweep around to the north,” Allen explained. “Anyway, since Bastogne appears to be cut off there was no need for you to keep the road westward open anymore. Hence, division decided to pull you back. You’re going to be the reserve for now.”

The young captain, hearing his new orders, snapped a quick a salute and left the room. He would eventually learn that his commander was right. For three critical days, his lone company of glidermen had seriously disrupted the German line of communication around Bastogne. In fact, tactically, Crossroads X had become a microcosm—a tiny version of Bastogne. Because it was denied the road junction, the 2nd Panzer Division had to travel farther out of its way to reach its next objective.

The German Offensive Peters Out

As early as December 20, the 2nd Panzer Division was already experiencing a fuel shortage that slowed its operations. In addition, the division eventually had to commit an entire Kampfgruppe to recapture the vital road junction so that the Americans could not threaten the critical bridgehead at Ortheuville to the west. Together with the roadblock obstacles around Champlon, which were the handiwork of U.S. Army combat engineers, the Germans were forced to slow their advance.

In the end, the constant disruptions and tiny battles sapped the strength of the 2nd Panzer Division. As a result, it ran out of gas within sight of its ultimate destination, the crossings at the Meuse River. Had von Lauchert’s division been able to reach the Meuse, the Battle of the Bulge might have ended differently. Thanks to the efforts of men like Robert MacDonald, Carmen Gisi, Mike Campana, Joseph Karpac, and the other members of Baker Company of the 1/401st, the German tanks sputtered to a halt and fell victim to Allied armor and the U.S. Army Air Forces on Christmas Day, 1944.

my dad was part of company b i wished i could have talked about his part in the war he’s gone now thanks for the post