By Don Hollway

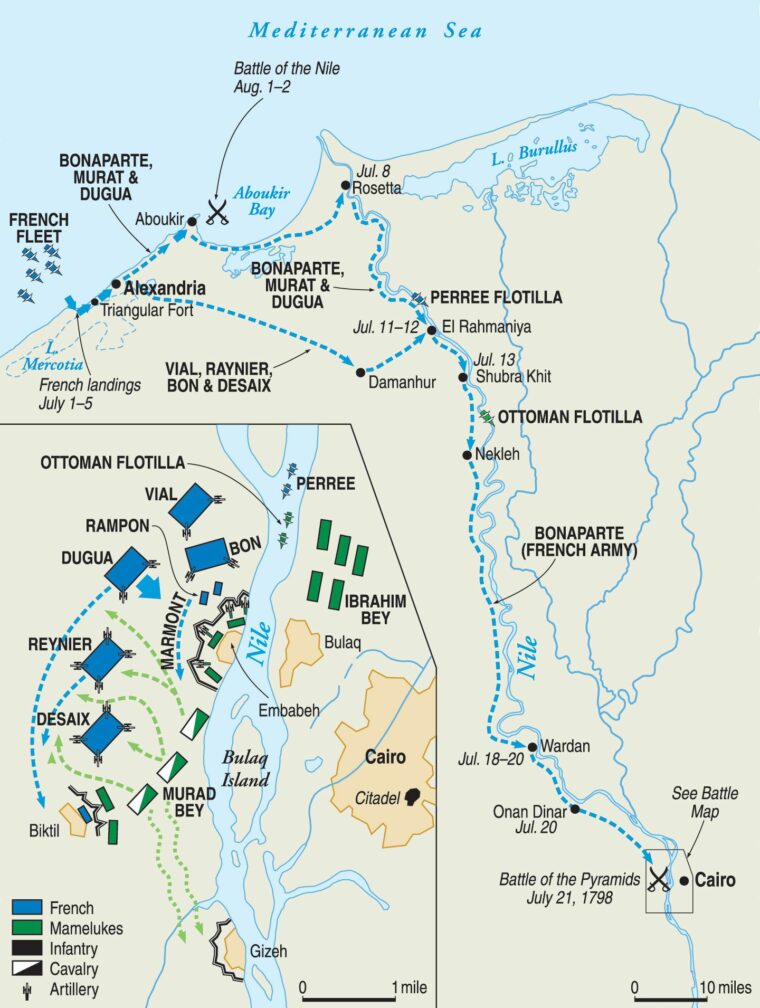

In May 1798 English spies in Toulon, on the French Mediterranean coast, stood aghast at the gathering of an invasion fleet three times the size of the Spanish Armada: 13 ships of the line, 40 frigates and smaller warships, and 130 cargo vessels bearing more than 17,000 troops, 700 horses, and 1,000 cannons. Waiting at sea, three more convoys brought the fleet to nearly 400 ships with approximately 55,000 men. Their destination was secret, but the fleet was assembling just five years after bloody-handed French revolutionaries had beheaded their king and queen and defeated every royalist nation, including Spain, Holland, Prussia, Russia, and Austria. Thus, there could be little doubt that the fleet was sailing against England.

So vast was the fleet that eight hours were required for all the vessels to put out past the flagship, the 120-gun man-of-war Orient. Aboard it stood General Napoleon Bonaparte, the 29-year-old upstart whose victories in Italy had rattled crowns throughout Europe. Of all those men at sail, only he and a few dozen subordinates knew that the invasion force’s true objective was not England, but Egypt.

The Directory then ruling France always desired to export its revolution across the English Channel, but as commander of France’s Army of England, Bonaparte knew his military prowess on land was matched by the Royal Navy’s at sea. “My glory has already disappeared,” he complained to his secretary, Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne. “This little Europe does not supply enough of it for me. I must seek it in the East, the fountain of glory. If the success of a descent on England appears doubtful, as I suspect it will, the army of England shall become the army of the East, and I will go to Egypt.”

A year earlier Raymond de Verninac, the French minister plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Empire, had captivated Napoleon not only with descriptions of the land of the pharaohs but also the ease with which it might be seized. The Sublime Porte, the Turkish imperial government in Istanbul, a French ally since 1536, controlled it in name only, through a governor, the pasha. Two dozen Mameluke beys, Europeans bought as slaves but raised to be free warriors, ruled as princes. Overthrowing them would merely be doing the Ottomans a favor, and Bonaparte saw no reason to bother Sultan Selim III for permission. “The Turkish Empire is crumbling,” he told the Directory. “The day is not far off when we shall appreciate the necessity, in order to really destroy England, to seize Egypt.”

Conquering the crossroads of the Middle East would restore to France the revenue and prestige lost with its own colonies in North America and the Caribbean, and simultaneously cut off England from its East India Company. The Directors no doubt also saw good reason to let their ambitious young general satisfy his thirst for power elsewhere. They consented to his expedition.

On May 10 Bonaparte arrived in Toulon. “Officers and soldiers,” he told the troops, “I shall now lead you into a country where by your future deeds you will surpass even those that now are astonishing your admirers, and you will render to the Republic such services as she has a right to expect from an invincible army.” He promised each man riches enough to buy six acres of land. Most of his cheering troops guessed that land would be in Naples, or Sicily, possibly England. Egypt, to them, was mostly Biblical legend.

Napoleon was religious only to the extent that it served his political purposes. To him, the legend of Egypt was that of Alexander, of pharaohs and Caesars, of Anthony and Cleopatra, of a lost civilization that had built monuments taller and more massive than any since attained by modern man. He had recently been elected as a member of the French Academy of Sciences and felt that the blood of the Revolution had not spoiled the lofty ideals of the Enlightenment. He planned not only a military conquest but also a scientific and archaeological expedition that would astound the salons of Paris. He enlisted Gaspard Monge of the Governmental Commission for the Research of Artistic and Scientific Objects in Conquered Countries to recruit interpreters, engineers, surveyors, cartographers, mathematicians, chemists, mineralogists, and zoologists. Altogether, 167 specialists sailed with the army.

The assembly of such a huge armada had not gone unreported in England, but its objective was still unknown. British Prime Minister William Pitt believed the French were targeting Ireland but could not be sure; England had withdrawn its Mediterranean fleet in 1796. Pitt hurriedly dispatched a squadron under one-eyed, one-armed Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson from Cadiz, which the Royal Navy was blockading, to intercept Bonaparte, or at least find out where he was going. Delayed by a gale that dismasted his flagship, Nelson did not reach Toulon until May 27, only to learn the French had been gone for eight days. Guessing they were bound for Naples, he hurried after them.

Napoleon was neither in haste nor headed for Naples. He stopped first at Malta, the island state centrally positioned to control both halves of the Mediterranean. Two thirds of the Order of the Knights Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem were French, and many were sympathetic to the French Revolution. From June 6, when the first French ships arrived, it took three days for all 400 to gather. “Never had Malta seen such a numberless fleet in her waters,” recalled an eyewitness. “The sea was covered for miles with ships of all sizes whose masts resembled a huge forest.” After the Knights Hospitaller made a show of resistance, costing the French three men, Napoleon simply offered them pensions for life. On June 11 they signed the island over to France.

On June 20 the British squadron, having found no French in Naples, transited the Strait of Messina. A passing Genoese brig informed Nelson that Bonaparte’s fleet had departed Malta heading east. Bonaparte’s fleet was 160 miles ahead, but it could travel no faster than their slowest transport, which was about three knots. When one of his screening frigates informed him the British were on his trail and catching up, Napoleon took a look at his maps and ordered a change of course toward Crete. The French fleet sidestepped, and on the foggy night of June 22-23 the British passed it in the dark, so close that Vice Admiral François Paul de Brueys, on the deck of the Orient, could hear their signal guns. By morning, on divergent courses, the two fleets were over each other’s horizons, and on June 27 the British reached Alexandria first. “It is impossible that the French should come to our country,” the city commandant told them. “They have no business here, and we are not at war with them…. Water and victual your ships, if you have to, but go away. If the French really think of invading our country, as you pretend, we shall thwart their undertaking.”

Believing Bonaparte must have headed for Crete or Turkey, Nelson sailed north in pursuit. Two hours after the last British ship vanished over the horizon, the lead French frigate, Junon, arrived from the west.

Upon sighting the land of the pharaohs, diplomat and artist Vivant Denon had been disappointed: “Not a single tree or habitation was visible. It wore the appearance, not of the melancholy of Nature, but of her destruction, of silence, and of death. The prospect, however, did not diminish the cheerfulness of the soldiers: one of them, pointing to the desert, said to another, ‘There, look at the six acres that are decreed you!’ raising a sarcastic laugh among his comrades.”

“When I arrived before Alexandria, and when I learned that the English had passed by there with superior forces a few days before, I decided to land my troops, despite the horrible storm that was raging,” reported Bonaparte. Alexandria’s harbor was too small, shallow, and well defended to assault. The French landed at Marabut, a fishing village eight miles to the west. In high seas, the operation lasted throughout the night. Men lowered themselves down into launches and longboats bobbing alongside the transports and battleships. Horses were hoisted overboard and made to swim. In the tossing waves it took some crews eight hours to row to the beach. Boats capsized, men drowned, but at 3 am, still lacking artillery, mounts, and even water, Bonaparte had three divisions ashore and on the way to Alexandria. The gale dissipated, and when the sun came up it gave the French their first taste of the Sahara. “It was thirst which inspired our soldiers in the capture of Alexandria,” wrote Lieutenant Louis Thurman after a five-hour march. “At the point the army had reached, we had no choice between finding water and perishing.”

Without artillery, the city walls had to be breached the hard way. In the first five minutes, General Jean-Baptiste Kléber took a musket ball in the face and General Jacques-François Menou was wounded six times and thrown from the ramparts. Though both survived, 300 Frenchmen were killed in the assault. “Our soldiers considered this attack to be child’s play,” wrote civilian outfitter François Bernoyer.

“The Turks had mounted a wretched gun upon a pile of stones: they loaded it without cartridges or shot, but with loose powder and stones, and fired it with a lighted brand,” wrote General Anne Jean Marie Rene Savary. “We soon learned how perfectly ignorant they were of the science of artillery.”

The defenders neglected to close a city gate. Once inside, the French troops took the fighting house to house. A sniper took a shot at Napoleon and hit his left boot, for which he was hunted down and killed. Defenders making a last stand in a mosque were slaughtered. Adjutant General Pierre François Joseph Boyer, himself wounded in the fighting, wrote, “Men and women, old and young, even children, all were massacred. After about four hours, the fury of our soldiers was spent at last.” Approximately 800 Egyptians were killed or wounded. By 12 pm Alexandria was an outpost of France.

Bonaparte issued a proclamation, declaring in part, “Once you had great cities, large canals, a prosperous trade. What has destroyed all of this, if not the greed, the iniquity, and the tyranny of the Mamelukes? The French have shown at all times that they are the particular friends of the Ottoman Sultan and the enemy of his enemies. The Mamelukes, on the contrary, have always refused to obey him; they never follow his orders and follow only their whims. Happy, thrice happy are those Egyptians who side with us. But woe, woe to those who side with the Mamelukes and help them to make war on us.”

In Cairo, Turkish governor Abu Bakr Pasha summoned the beys. Murad Bey, the Circassian Emir al-Hadj, de facto military commander, told him, “The French could not have come to this country without the consent of the Porte, and you, being its minister, must have had knowledge of their projects. Fate will help us against you and them.”

Facing giant, blond-bearded Murad, who was said to be capable of beheading an ox with one slash of his scimitar, the pasha must have realized just how slight was his hold on Egypt. “Cast these thoughts from you,” he told the beys, “be courageous and forthright, rise up like the brave men you are and prepare to fight and resist by force, leaving the outcome to God!”

Ibrahim Bey, the Sheik el-Beled, administrative head of the country, had heard, “The Infidels who come to fight you have fingernails one foot long, enormous mouths, and ferocious eyes. They are savages possessed by the Devil, and they go into battle linked together with chains.”

Murad Bey headed north with 4,000 mounted Mamelukes, their retainers, the city militia, and sundry Bedouin cavalry and fellahin, peasant soldiers, about 20,000 in all. As he advanced up the west bank of the Nile, the Egyptian navy, a gunboat flotilla, moved alongside in support. Meanwhile, Ibrahim Bey and Abu Bakr Pasha assembled the rest of the army at Bulaq, Cairo’s river port on the east bank.

In Alexandria, Captain Jean-Baptiste Perree loaded three gunboats, a galley, and an Arab xebec renamed Le Cerf with ammunition, provisions, and civilians including Secretary Bourienne and scientist Monge. They set off up the Nile as a riverine fleet in support of the advance to Cairo with a division marching alongside. In the interim, General Louis Charles Antoine Desaix took four divisions out along the dry bed of the Alexandria-Nile Canal, about 45 miles, across the Sahara, in July. “Unless the entire army crosses the desert with lightning speed, it will perish,” he wrote.

“The army left Alexandria on the night of the very day of the capture of that city,” wrote Savary. “Our march was across a white surface of country, which cracked like snow under our feet; on tasting, it proved to be salt.”

“Ordinarily, that plain is irrigated by the flooding of the Nile,” wrote Bonaparte. “We were at the time when the Nile is at its lowest level. All the cisterns were dry, and no water could be found.” Towns along the way amounted to nothing more than abandoned mud huts and dry wells. As soon as the sun came up, men began tossing aside their woolen clothing and even their biscuit rations, inedible without water.

Any stragglers fell victim to Bedouin tribesmen. “These enemies were so skillful and so well aided by their horses, known to be the best in the world, that they swooped down on our troops, seizing a man from the ranks, lifting him up and disappearing in a flash,” wrote General Balthazard Grandjean,

“Pity the unfortunates who fell into their hands,” wrote General Charles Antoine Morand. “They stripped them, and before killing them would appease their abominable passions on them.”

Yet the Bedouin were but a minor nuisance. “General Desaix has received intelligence that Murad Bey is on his march and, at this moment, perhaps at only two days’ distance from us,” wrote General Jean Louis Ebenezer Reynier.” On July 10 a scout force of 300 Mameluke horsemen had to be driven off with cannon fire.

The next day the French divisions assembled at El Rahmaniya on the banks of the Nile. Men fell gratefully into the water and gorged themselves in fields of watermelon with predictable effect. As a result, nearly all suffered from diarrhea.

Murad Bey, meanwhile, arrived at the village of Shubra Khit, about eight miles to the south. Bonaparte knew the best way for his troops to forget their suffering was to give them a victory. Overnight he marched them upriver, and on the morning of Friday, July 13, they stood ready for battle.

“At sunrise martial music suddenly rang out; the Commander in Chief had ordered the playing of ‘La Marseillaise,’” wrote Lieutenant Jean-Baptiste Vertray of Reynier’s division.“A column of Mamelukes came out of the palm trees to the army’s left and made a semicircle as if to envelop us.”

The Egyptians made a fearsome sight. Lieutenant Nicolas Philibert Desvernois never forgot it. “In the background, the desert under the blue sky; before us, the beautiful Arabian horses, richly harnessed, snorting, neighing, prancing gracefully and lightly under their martial riders, who are covered with dazzling arms, inlaid with gold and precious stones,” he wrote. The Mamelukes, though, may not have achieved their intended effect. “This spectacle produced a vivid impression on our soldiers by its novelty and richness,” noted Desvernois. “From that moment on, their thoughts were set on booty.”

Ever the student of warfare, Bonaparte had read of the infantry squares used by the Austrians and Russians in their wars with the Ottomans a decade earlier. His French squares were in fact hollow rectangles, 300 yards across, 50 yards deep, with nine cannons at each corner for overlapping fields of fire. Captain Jean-Pierre Doguereau remembered, “Our squares were formed; the artillery on the corners and in the intervals; the cavalry and the baggage in the centre. This formation, which presented them [the Mamelukes] with masses of men and firepower on all sides, stunned them.”

Upon learning the French had almost no cavalry, Murad Bey had laughed and bragged that his horsemen would cut through them like watermelons. Each Mameluke fought in the ancient manner. “Somehow attached to his horse, which appeared to share all his possessions,” wrote a French colonel, “with the sabre hung from the wrist, he fired his carbine, his blunderbuss, his four pistols and after having discharged his six firearms, flanked the platoon of tirailleurs passing between them and the line with a marvelous dexterity. However, we soon recognized that these men, individually of an unmatchable bravery, had no idea of combined movements or mass charges.”

All morning the Egyptian horse circled the French squares, seeking entry and finding none. “A few of the bravest, without doubt to encourage the others, charged our tirailleurs,” wrote Doguereau. “Death was the price they paid for their audacity.”

Out on the water, however, it was another story. Perree’s five ships met seven Egyptian gunboats, expertly manned by Greek sailors, supported by cannons in Shubra Khit and musketry from both sides of the river. Lieutenant Laval Grandjean of the naval contingent recalled, “The Mamelukes, Arabs and peasants ran out in a crowd, swarming towards us with hideous cries, some began hauling their boats down from the bank, others threw themselves into the water, all coming to attack us on board.”

By the time Bonaparte considered the land battle won and ordered his divisions to the riverbank in support, Perree’s galley and two of his gunboats were already lost. “Already several ships had been boarded by the Turks,” reported Bourienne. “Their crews were being massacred under our eyes with barbaric ferocity, and the captors displayed their heads to us holding them by their hair.”

The survivors, including several scientists, scrambled aboard Le Cerf. Monge helped to reload its guns. The two fleets fired more than 1,500 rounds. The Egyptian flagship caught fire and, when the flames reached its powder magazine, detonated. “The explosion made men fly up in the air like birds,” wrote Arab chronicler Nikula ibn Yusuf, al-Turki (Nicholas the Turk).

The sight caused the French to burst into laughter and took the fight out of the Egyptians. Their fleet turned back upriver. The Mamelukes ashore withdrew, leaving behind 600 dead. The French army suffered not one casualty. Its little navy, however, lost 70 men. “Twenty of my men were wounded, and several killed,” reported Perree. “I lost my sword and a little bit of my left arm.” Bonaparte promoted him to rear admiral.

Upstream the river was so shallow that the flotilla could go no farther and so winding that to follow it would have added days to the march. The French left its banks and paralleled its general course through the desert, over and across dried-up irrigation canals. Quartermaster Sergeant Charles François remembered, “Men were dying, suffocated by the heat. It felt like passing in front of a very hot oven. Several soldiers committed suicide.” Sunstruck, starving, dysenteric, it took them a week to reach the fork of the Nile, north of Cairo, where a spy informed Bonaparte that the Mamelukes awaited him on both sides of the river. Ibrahim Bey was still at Bulaq, north of the city on the far bank, with most of the able-bodied men of the city manning barricades and cannons. On the French side, Murad Bey had fortified the village of Embabeh.

For Napoleon this was a gift from Allah. If Murad had withdrawn across the Nile it would have compelled the French to make a riverine assault under fire. Instead, Bonaparte had the luxury of fighting Murad first and Ibrahim at his leisure. Murad’s and Bonaparte’s forces were well matched, the French at 25,000 and the Egyptians at 6,000 mounted Mamelukes with perhaps 15,000 infantry. The French were on their last legs from heat and hunger; their square formations meant that, for most of the battle, only their forward-facing elements would be engaged at any one time. The Egyptians were fresh, well mounted, fighting from prepared positions, and could bring all their numbers to bear at once.

At 2 am on Saturday, July 21, the French set out. Driving enemy advance scouts before them, they arrived 12 hours later, during the hottest part of the day, on a watermelon field north of Embabeh. In the distance glittered the minarets of more than 300 mosques in Cairo, then a city of 500,000 people that was larger than Paris, and in the Ottoman Empire, second only to Istanbul. Rising into the sun even farther south were the crests of the Pyramids at Giza, though in 1798 they were half-buried in sand. But Napoleon certainly knew that, on some of the most historic ground known to man, he was about to make history again. He is famously said to have told his men, “Soldiers! From the heights of these pyramids, forty centuries are looking down on you,” but in reality his troops were spread out across several miles, and few could have heard. Even fewer knew what the Pyramids were or had the slightest idea what he was talking about. Adjutant-Major Lieutenant Pierre Pelleport did hear, but scoffed, “It was Greek to most of our comrades.”

“The squares were halted between two villages surrounded by gardens that guarded their flanks and hid the Mamelukes,” recalled Morand. The entrenched Egyptian line blocked the way, its right flank anchored in Embabeh and its left in the village of Biktil. “The majority rallied beneath the walls of a garden not far from our right-wing Divisions,” wrote Morand.

Bonaparte wanted this to be his last battle in Egypt. “I ordered the divisions of generals Desaix and Reynier to take up a position on the right, between Giza and Imbaba [sic], in such a manner as to cut off the enemy from communication with Upper Egypt, which was his natural retreat.”

If the two divisions got behind them, the Mamelukes would be trapped against the river. But since Shubra Khit, Murad Bey had had time to reconsider his tactics. There were only two ways the French square could be defeated: before it formed or by pounding it to pieces with artillery. To this purpose he had hidden most of his cavalry in Biktil and 40 guns in Embabeh. The decision of which to employ first was made for him by the advance of the French right. Marching into and out of dried-up irrigation canals and through thickets of palm trees, the squares became disorganized. Murad saw his chance.

“We first saw three Mamelukes, who came to reconnoitre the Division,” remembered Morand. “It appears that after they reported back, they decided to charge.”

With no more warning than that, at about 3:30 pm the Mameluke cavalry on the Egyptian left burst out of Biktil upon Desaix and Reynier. “Only a few officers and the generals saw the movement of the Mamelukes, which was so rapid that there was only just time to fire,” recalled Morand.

“General Reynier gave the order, ‘Form your ranks,’” recalled Vertray. “In the blink of an eye, we were arranged in a square six men deep, ready to withstand the shock. This movement was executed with a precision and coolness under fire that was truly remarkable.”

Civilian Bernoyer saw no such thing. “There was great confusion around me,” he wrote. “Our general was in such a stupor that he found himself incapable of making a decision. A Dragoon [mounted infantry] captain took the initiative to rally us.”

“General Bonaparte did not want us to be engaged against that redoubtable cavalry,” admitted one of the cavalry officers, “believing that the number of mounted dragoons was too weak for them to receive a Mameluke charge in line. This caution, perhaps justified, caused utter mortification among the cavalrymen who were wholeheartedly looking forward to the moment when they could measure their blades against the Muslim scimitars.”

With the cavalry protected in their hollow centers, the French squares locked down in position, presenting a hedge of bayonet points, musket barrels, and cannon muzzles to the oncoming Egyptians, and not a moment too soon. “The last stragglers were not yet in their ranks when the line began firing on the Mamelukes, who were 200 paces away,” wrote Savary.

“We let them approach within 50 feet and then greeted them with a hail of balls and grapeshot that caused a large number of them to fall on the field of battle,” wrote Bonaparte.

In Reynier’s division, Vertray remembered the sight of the screaming Egyptians thundering down on his position. “The soldiers fired with such coolness that not a single cartridge was wasted, waiting until the very instant when the horsemen were about to break our square.”

“We finally saw those terrible horsemen face to face, whose scimitars could reputedly cut a man in half,” wrote a French dragoon. “With savage cries they threw themselves on our Divisional squares, but all their impetus was broken on our grenadier’s bayonets.”

“A good number fell into our ranks where, in their impotent rage, they fought for their lives with their daggers,” wrote Morand.

“It was imperative for troops such as us to resist these fearsome charges by the enemy. Our brigade was at this time composed almost exclusively of battle-hardened warriors accustomed to victory; besides, we knew that it was all or nothing,” recalled Vertray.

Reynier was extremely proud of his division. In the face of such fire, the Egyptians could be excused for thinking the enemy surely had massed all their guns to the front. They rode around the sides of the squares, seeking an unprotected rear. Indeed, some of the unemployed French back there had taken the opportunity to leave ranks for more pressing needs.

“When the Mamelukes were passing through the interval between the two Divisions, they found themselves pell-mell with a large number of our soldiers, who were looking for water in the surrounding gardens and were returning after hearing the gunfire,” wrote Morand. “This forced us to cease firing or at least reduce it and to aim very high.”

Still, the Egyptians between Desaix and Reynier found themselves in a killing ground. They had advanced into the gap between the two divisions and received heavy fire that decimated their ranks.

“Caught in the crossfire from two Divisions, they fell into the interval where the cannon were placed,” remembered Morand. “In the crossfire, they could not escape, except through a narrow gap, guarded by a detachment of carabiniers waiting in ambush, who shot them at point-blank range.”

Across the river, Somali cleric and chronicler Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti could hear the near-constant popping of French muskets and cannons, like “a cauldron boiling on a crackling fire.” Most of the citizenry had come out with Ibrahim Bey to see the foreigners defeated. “The eastern army, seeing the battle in progress, began to scream at the top of their voices … as if that were enough to be victorious,” he wrote.

“The number of corpses which lay all around us was soon considerable,” recalled Vertray, who recorded a curiosity of the battle noted in many other French accounts. “The clothes of the dead and wounded Mamelukes burned like tinderwood … the flaming wads from our rifles penetrated their exotic uniforms, which floated in the air like gauze embroidered with gold and silver … they all wore chiffon chemises and cloaks of silk, with their weapons encrusted with ivory and finely cut gemstones.”

With the Egyptian left spent, Bonaparte determined to crush its right. He therefore ordered General Louis Andre Bon’s division, which was by the Nile, to launch an attack on the portion of the enemy that was entrenched.

As Bon advanced on Embabeh, his square began taking fire from the cannons emplaced among the buildings. From the far side of the river, Ibrahim Bey ordered his guns to add to the bombardment. “The entrenched artillery opened fire, supported by boats on the Nile,” remembered Doguereau. “We were momentarily stunned. This fire was very murderous on a corps formed so deep; files of five or six men were cut down.”

With heavy cannonballs slashing through their ranks, the French squares threatened to come apart. As on the left, on the right Egyptian horsemen rode out to exploit the opening. “They threw themselves forward in a mad charge. Our order was not to move,” remembered François. “We hardly breathed; brigade commander [Auguste de] Marmont had ordered us not to fire until he gave the command. The Mamelukes were almost upon us. The order was finally given, and it was real carnage.”

The slaughter of horses and riders on the French right was repeated on its left. “The sabers of the enemy cavalry met the bayonets of our first rank,” recalled François. “It was an unbelievable chaos: horses and cavalrymen falling on us, some of us falling back…. I was by the flag and I saw right beside me Mamelukes, wounded, in a heap, burning, trying with their sabers to slash the legs of our soldiers in the front rank…. I have never seen men braver and more determined.”

Bravery and determination, though, counted for nothing against powder and steel. “Bon’s Division doubled the pace; the charge was beaten,” wrote Doguereau.

With the Egyptian cavalry again broken on its squares, the French infantry resumed the assault. “We quickly marched forwards at the pas de charge to close with the enemy and assault the trenches,” he wrote.

If the Mameluke horse was no match for the French foot, the Egyptian fellahin militia had no choice. They were merely simple peasants armed with nothing more than clubs. Massed French bayonets soon cleared the trenches of the enemy. “At point-blank range we fired at the Mamelukes as they were fleeing from the entrenchments on all sides,” Doguereau wrote.

“A large number of emirs and soldiers from the forces on the Cairo bank of the river decided to cross the river to aid their fellows on the other shore,” wrote al-Jabarti. “Amongst these was Ibrahim Bey himself. There was a great confusion amongst the men because there were only a few rowing boats.”

At last came the moment for the French horsemen to finish the job. “Our cavalrymen positioned inside the square fired along with the infantrymen,” wrote a French dragoon officer, “until the moment when, weary of their fruitless attacks, Murad’s Mamelukes turned tail and followed their fleeing commander into the desert. We were then permitted to pursue the vanquished, of whom we were able to sabre only a very small number, for they were mounted on admirable horses, whose speed thwarted our efforts.”

But some of the Egyptian horsemen still sought single combat. “A distinguished Mameluke bey with a fine long beard paraded himself before the front line of Bon’s division,” wrote Lieutenant Desvernois. “At the sight of this insolent enemy I was overcome with anger and bringing my magnificent Arab steed to the gallop I broke out like lightning from the ranks of our divisional square and joined battle with this audacious bey. Bullets rained around us, but we did not heed them. With a pistol shot I knocked him from his saddle. He fell from his mount and approached me on hands and knees.”

Desvernois motioned for the Mameluke bey to march himself into captivity, but his offer of mercy was misplaced. Far from trying to hold the Frenchman off, the Mameluke was trying to get close enough to cut his mount’s legs from under it. He leaped up under the horse’s neck, grabbed the reins, and slashed at the Frenchman. The horse, rearing, took the blow on its head. Desvernois had no other choice but to strike him over the head repeatedly in order to kill him. When the Mameluke’s turban came off, it was found to have 500 gold coins sewn inside, according to Desvernois.

Meanwhile, the French infantry poured through the dirt streets of Embabeh and Biktil. “We arrived in their camp with our bayonets lowered,” recalled Laval Grandjean, now fighting ashore. “We bore down on them with the bayonet and the majority found no means of escaping death except by throwing themselves into the Nile and swimming.”

“We cut off a group of the enemy so that they had to throw themselves in the Nile where many of them drowned and those that we reached were bayoneted,” wrote Private Pierre Millet.

Approximately 1,500 Egyptians, seeing no escape to the water, made a stand in a trench. They were cut down to the last man. “The carnage was atrocious,” remembered Millet. “The corpses of men and horses presented a horrifying spectacle, so bloody was the massacre.”

Egyptians fleeing from the west bank floundered among Egyptians attacking from the east bank. The French showed no mercy but brought their cannons to the riverside. Morand remembered, “We fired canister at the thousands of heads we saw in the water.” The Nile became a crocodiles’ feast of frantically swimming men spattered with musket balls and grapeshot, drowning, dying, and finally swept away by the current “The combat had lasted but more than two hours, but two hours of indescribable horror,” wrote Nicholas the Turk.

The Egyptians lost approximately 800 men. The French suffered 29 dead and 1,200 wounded. Their triumph, though, was short-lived. Eleven days later, at 10 pm on the evening of August 1, Kléber’s garrison in Alexandria saw a flash of light and heard an explosion from the direction of Aboukir Bay 20 miles away: the French flagship Orient, blowing up at the Battle of the Nile. Nelson had returned, demolished the French fleet, and cut Bonaparte off from home. However, the ensuing British blockade had an unintended effect: it made Napoleon more than just a conquering general. He became a head of state.

“The loss of the fleet convinced General Bonaparte of the necessity of speedily and effectively organising Egypt,” wrote Bourienne. “War, fortifications, taxation, government, the organization of the divans [government councils], trade, art, and science, all occupied his attention.” Under Napoleon’s administration Europe rediscovered Egypt: the long-forgotten ruins at Thebes, Luxor, and Karnak; the Rosetta Stone, which ultimately led to the deciphering of ancient hieroglyphics.

It might even be said that Bonaparte’s Egyptian Campaign presaged his conquest of Europe. His experience in governance gave him the confidence to return home, depose France’s Directory, and proclaim himself First Consul, then Emperor. His decisive defeat of the Egyptians along the Nile is certainly reflected in the tactics he used at Ulm and Austerlitz, Quatre Bras, and Ligny. His ill-fated march into Syria, culminating in the failed siege of Acre and subsequent plague-cursed withdrawal, foreshadowed the infamous 1812 advance to and retreat from Moscow. The impervious infantry squares that defied Murad Bey before the Pyramids would equally prove the undoing of Napoleon 17 years later at Waterloo.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments