By Phil Zimmer

General Georgi Zhukov had arrived at the Mongolia-Manchuria border in the early morning hours of June 5, 1939, after a grueling three-day trip from Moscow. He insisted on immediately questioning the Soviet defenders and touring the site of the recent border clashes with Japanese troops. Peering through his field glasses at the small figures scurrying about on the east bank of the Halha River and after tossing out sharply worded questions, Zhukov came to the belief that this was not another mere border clash with the Japanese. For years, Japanese troops had been probing the nearly 3,000-mile-long border that separated the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Soviet-protected Mongolia from the Japanese protectorate of Manchukuo, which was created shortly after the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931.

The energetic Zhukov filed a report at the end of his first day, saying this looked to be the beginning of a major escalation by the Japanese and the forces of Manchukuo. The Soviet 57th Corps did not appear up to the task of stopping the Japanese in Zhukov’s assessment. He recommended a temporary holding action to protect the bridgehead on the east bank of the Halha River, which was called Khalkhin Gol by the Soviets, until substantial reinforcements could be mustered for a counteroffensive.

One day after submitting his report to Moscow, the Soviet high command responded by naming the 42-year-old Zhukov to head the military effort, succeeding former General Nikolai Feklenko. The Soviets had tired of the Japanese incursions and were determined to make a point in the East as war clouds continued to build over Western Europe.

Both sides were about to square off in a decisive struggle that became known as the Nomonhan Incident, which lasted several months with upward of 50,000 killed or wounded. More than 3,000 miles from Moscow, the small undeclared war went largely unnoticed in the West, but it was to have a profound influence on the coming world war. The defeat at Nomonhan caused the Japanese to turn southward toward the oil-rich East Indies and prompted the Imperial Japanese Navy to consider a preemptive strike on the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor. The use of combined arms and overwhelming force under Zhukov was later to play a significant role in the eventual Soviet repulse of the Nazi thrusts at Moscow and Stalingrad.

Zhukov’s Opportunity to Prove Himself

In reviewing the situation at Nomonhan, Zhukov realized that he had some skin in the game. Stalin’s purge of the Red Army had just come to an end, with its leadership cadre, including Commander in Chief Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky and more than half of its senior commanders were executed. This void opened opportunities for younger, talented, and savvy men like Zhukov if they could prove themselves and survive the rough and tumble atmosphere created by the bloody purges.

The bright, ambitious Zhukov, the son of peasants born some 60 miles east of Moscow, was determined to succeed. Once his June 5 report was filed, the Soviets provided substantial reinforcements to the young commander, including the 36th Mechanized Infantry Division; 7th, 8th, and 9th Mechanized Brigades; 11th Tank Brigade; and the 8th Cavalry Division. In addition, Zhukov’s newly named First Army Group received a heavy artillery regiment and a tactical air wing with more than 100 planes and a group of 21 experienced pilots, who had won combat citations while fighting in Spain.

The Soviets were aided by the fact that their military buildup occurred at Tamsag Bulak, 80 to 90 miles west of the Halha River and away from Japanese aerial observation. However, the nearest Soviet rail line was at Borzya, some 400 miles west of the Halha River. Japanese self-confidence and racist stereotypes of their Soviet opponents also played a role. Their railhead was only 50 miles away, and they believed that the Soviets simply could not concentrate a large combined armed force so far from their nearest railhead. Supplies would have to be transported by truck over dirt roads or over flat, open territory, making the convoys vulnerable to air attack if matters escalated. Japanese commanders also rejected the idea that the Soviets could adapt themselves to defeat Japanese tactics, which had proven so successful earlier in Korea, Manchuria, and China.

In short, the Japanese did not believe the Soviets would rise to the challenge over such a small sliver of territory in such a faraway place. While the Japanese claimed the border to the Halha River, which flows northwest into Lake Buir Nor, the Soviets contended the border ran through the mud-brick hamlet of Nomonhan, some 10 miles east of the river. At its widest point, the disputed backwater area was less than 12 miles wide and approximately 30 miles long.

Tensions Rise on the Japanese-Soviet Border

Japanese-Soviet antagonism ran deep, dating back even before the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905 as the two powers struggled for years to assert dominance over parts of China, Korea, and Manchuria. After their defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian czars were forced to recognize Japan’s interests in Korea, and they ceded the Liaoutung Peninsula, renamed Kwantung by the Japanese. Kwantung contained the port of Dairen and the important naval base of Port Arthur. A few years later the Japanese established a special force, the Kwantung Army, to administer the area. The army was to later spearhead Japanese expansion on the Asian mainland.

For its part, the Russian bear managed to paw Outer Mongolia from China in 1911, making it a protectorate called the Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR). World War I and the subsequent Russian Revolution caused considerable internal strife as the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. The resulting power vacuum and a weak China enabled the Japanese to take Manchuria. The poorly defined borders created additional uncertainty. In June 1937, Japanese forces fired on Soviet gunboats, killing 37 sailors in the Amur River that flowed between the USSR and Manchukuo. Border problems arose again in the summer of 1938 where the poorly defined borders of Korea, Manchukuo, and the Soviet Union met. The skirmishes at Changkufeng Hill provided a reminder to Stalin that the Imperial Japanese Army still threatened his eastern flank as matters heated up in Europe.

First Clashes on the Border

Although the reports differ considerably, the initial conflict at Nomonhan began on May 11, 1939, when a Japanese-backed force of provincial Manchukuo cavalry clashed with a Mongolian-Soviet patrol north of the Holsten River that flows westward to the Halha River. Japan’s Kwantung Army, which operated with some autonomy from Tokyo, decided to take matters into its own hands despite the fact that its eight divisions faced 30 Soviet divisions along the mutual border running from Lake Baikal to Vladivostok on the Pacific. Matters continued to escalate, and the next day a flight of Japanese light bombers attacked an MPR border post on the west bank of the Halha River, indisputably within the borders of the Soviet-backed country. MPR troops then crossed the fast-flowing 100- to 150-meter-wide Halha River and took up new positions between the river and Nomonhan as combat resumed.

The Japanese saw this as a direct challenge to the Kwantung Army’s 23rd Division, an undermanned and poorly supported unit assigned to the backwater area. The 23rd had thinly armored tankettes armed only with a machine gun, and 40 percent of its 60 artillery pieces were Type 38 short-range 75mm guns dating back to 1907. The artillery regiment had a dozen 120mm howitzers, and most of the artillery was horse drawn. In addition, each infantry regiment had four rapid-fire 37mm guns and four 75mm mountain guns, but the division lacked high-velocity, low-trajectory guns appropriate to the terrain and necessary to handle oncoming tanks.

The Japanese Repulsed at the Halha River

On May 20, Japanese aerial reconnaissance discovered the Soviet buildup near Tamsag Bulak. The Japanese pulled together a force of 2,000 men to attack the enemy troops that had crossed the Halha River, starting with a two-pronged drive 40 miles south from Kanchuerhmiao along the east bank of the Halha. Four infantry companies and additional troops from Manchukuo were to push west from Nomonhan to help pin and destroy an approximately 400-man force of Soviet-MPR troops. That should have worked, except the Japanese failed to consider the possibility that the Soviet units spotted at Tamsag Bulak would be committed.

The Japanese had substantially greater numbers, and they surprised the Soviet-Mongolian forces near Nomonhan. The Mongolian cavalry was routed and forced back, causing the Soviets to pullback as well toward the Halha River. As they neared the river, the fighting intensified and Soviet artillery and armored cars forced the Japanese forces to dig in on a low hill several miles east of the Halha. Because of faulty radio equipment, a 220-man Japanese unit under Lt. Col. Azuma was not kept apprised of the changing picture near the bridgehead. He continued south, unaware that the main Japanese force had been deflected and forced to dig in well away from the river crossing. Azuma’s force was spotted, and additional Soviet artillery was brought east across the Halha to further protect the bridgehead.

The main Japanese force was now bogged down, dug in and under fire some two to three miles away, while Azuma’s lightly armed force was trapped by heavy fire. Azuma was nearly surrounded, with enemy infantry and cavalry attacking while heavy bombardment came from both sides of the Halha River. His cavalry dismounted and struggled to dig defensive positions in the sand. He could retreat northward, but doing so without orders would be a criminal offense punishable by death under the Japanese system. The artillery barrage continued and destroyed Azuma’s remaining trucks and the unit’s small reserve of ammunition. Only four men in his command managed to escape that night with the rest killed or captured. The main Japanese unit was not able to make progress, and three nights later it pulled back to Kanchuerhmiao. Japanese casualties neared 500, with one-fourth attributed to the main unit.

The Soviets and Japanese Reinforce

Although the Soviets had forced the enemy from the field, little mention of that fact was made at the time by either side. The Kwantung Army continued to assure Tokyo that it planned to avoid prolonged conflict, telling superiors that the Soviets would not be able to deploy large ground forces around Nomonhan. The Japanese forces, however, did request river-crossing equipment and craft, which should have alerted Tokyo that their army might be planning forays west across the Halha River into mutually recognized Mongolian territory. Moscow was growing suspicious of Japanese actions, and Zhukov was pulled from his duties as deputy commander of the Belarusian Military District in Minsk and sent east to investigate the disputed border area.

With Zhukov now on the scene, the Soviet buildup continued at Tamsag Bulak. On the other side, Japanese confidence was high, and the Imperial forces remained largely unaware of either the size of the buildup or the change in the enemy’s command with the arrival of Zhukov. The Soviet-MPR bridgehead east of the Halha was gradually expanded during the first half of June with no response from the Japanese. Soviet strafing raids east of the river did cause concern at Japanese headquarters. The Japanese decided to respond in kind to the air attacks to send a strong message to the Soviets, a decision that dramatically escalated the situation. Japan’s 7th Division was to be pressed into service to assist the relatively new and understrength 23rd Division. The 23rd was to be reinforced with 180 planes, a strong strike force of two regiments of medium and light tanks, an artillery regiment, and an infantry regiment. Japanese strength would grow to some 15,000 men, 120 artillery and antitank guns, 70 tanks, and 180 aircraft.

The Japanese remained exceptionally confident—so much so that they cut back the aerial reconnaissance west of the Halha so as not to alert the enemy. They were unaware that they were now facing a Soviet force of some 12,500 men, 109 artillery and antitank guns, 186 tanks, 266 armored cars, and more than 100 planes. Although the Japanese may have had a modest advantage in some categories, it was more than offset by the Soviets’ six-to-one armor advantage, which proved crucial in the relatively flat, open terrain.

Seizing Air Superiority

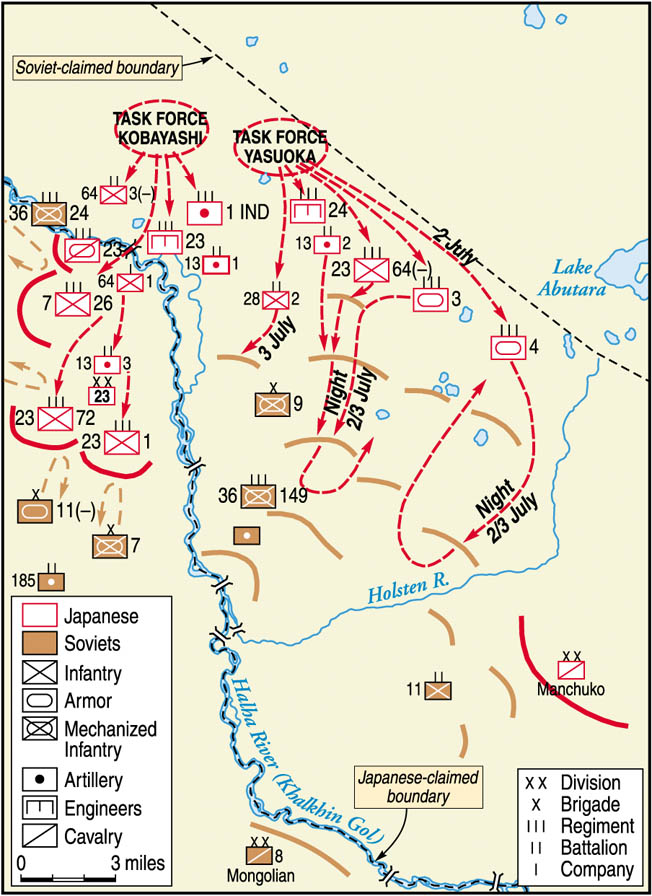

The Japanese plan of attack was rather straightforward. The main body of the 23rd Division would seize the Fui Heights, a pancake-shaped raised area located on the east bank of the Halha some 11 miles north of the confluence of the Halha and Holsten Rivers, where much of the fighting would occur. The 23rd Division and related units would cross the Halha near the Fui Heights on a freshly built pontoon bridge and move southward along the west bank of the Halha toward the Soviet bridge. At the same time, another force under Lt. Gen. Yasuoka Masaomi would move south along the east side of the Halha to engage the Soviet and MPR units and pin them between the two advancing forces near the Soviet-built bridge located near the confluence of the two rivers.

The Japanese planned to neutralize Soviet airpower with a preemptive strike at the Soviet base near Tamsag Bulak, located well inside the MPR. The Kwantung Army kept this component of the plan secret from Tokyo, concerned that higher ups would not approve. The general staff in Tokyo did learn of the planned air attack and went on record opposing it, but the semi-independent Kwantung Army actually elected to move the air attack two days forward to June 27. The Japanese surprise air attack caught a group of newly arrived Soviet airmen flat-footed. Returning pilots claimed 98 Soviet planes destroyed and 51 damaged, while the Japanese reportedly lost only one bomber, two fighters, and a scout plane. In short, the Japanese had achieved air supremacy over the Halha at the start of the Kwantung Army’s July offensive.

Crossing the Halha River

The Kwantung Army was ecstatic over the results of the air attack, but it received a severe rebuke from Tokyo. The Kwanting commanders resented the desk jockeys at the general staff and continued to believe in a need to maintain its dignity and maintain the border against what it perceived to be Soviet incursions. The Japanese plans went forward, and on July 1 the Japanese took the Fui Heights east of the Halha. Then, on the moonless night of July 2-3, the Japanese managed to build a pontoon bridge on the Halha River across from the Fui Heights. By early morning, the 26th Regiment and the 71st and 72nd Infantry Regiments began the slow crossing on the narrow bridge. The heavy armored vehicles had to remain behind, but the 18 37mm antitank guns, 12 75mm mountain guns, eight 75mm field guns, and four 120mm howitzers made it across undetected with all the infantry by nightfall.

The Soviets were now vulnerable with the enemy moving southward undetected on the west bank toward their bridgehead while facing a Japanese tank and infantry force on the east bank. Again the Japanese caught the Soviets by surprise when Yasuoka’s tanks attacked in the early morning hours of July 3, with guns blazing amid a passing thunderstorm. The startled Soviet 149th Infantry Regiment scattered before the tanks.

Zhukov, still apparently unaware of the Japanese presence on the west bank of the Halha, ordered his 11th Tank Brigade and related units north toward a hill called Bain Tsagan, located on the west bank. In the early morning hours of July 3, the Japanese, with their rapid-firing 37mm antitank guns and armor-piercing shells, mauled the Soviets. Zhukov, now realizing that a large Japanese force had crossed the Halha and was threatening his position, ordered the remainder of the 11th Tank Brigade, 7th Brigade, 24th Regiment, and an armored battalion of the 8th Mongolian Cavalry Division against the southward-moving Japanese force.

The Soviet armor had little infantry support, enabling the Japanese infantry to swarm over the Soviet vehicles, prying open hatch covers and destroying many of the tanks with gasoline bombs. Successive Soviet attacks were dealt with by the Japanese, who quickly found that the Russian gasoline tank engines could be taken out by gunners and gasoline bombs. However, by that afternoon unrelenting Soviet counterattacks and ranged-in artillery forced the Japanese to begin digging defensive positions on the west bank of the Halha just south of Bain Tsagan.

An Untenable Position

Zhukov then massed more than 450 tanks and armored cars in the area against a Japanese force that had left its armored vehicles behind before crossing the shaky pontoon bridge over the Halha. The only hope then lay with Yasuoka’s force, which had proceeded southward on the east side of the Halha. If that force succeeded, it would relieve pressure on Komatsubara’s embattled unit on the west bank. Yasuoka’s initial efforts were successful in crushing the first lines of Soviet artillery, but successive lines of Soviet infantry, tanks, and artillery slowed them and inflicted heavy losses. The Japanese Type 89 medium tank with its low-velocity 57mm cannon and relatively thin 17mm armor proved a poor match against the Soviet antitank guns and BT 5/7 tanks and armored cars. And the Soviets had another trick up their sleeves east of the Halha in the form of Japanese-produced piano wire coiled nearly invisibly as part of the defensive works. The wire entangled the gears and wheels of the Japanese light tanks like butterflies in a web, enabling Soviet artillery to zero in and finish off the tanks.

Making matters worse for the Japanese, Yasuoka’s infantry units were not able to catch up with the tanks, so the two forces fought separately and less effectively. By evening, his forces slowed, with the infantry dug in well short of the Soviet bridgehead. At that time, only 50 percent of the Japanese tanks were operable and able to withdraw to the initial jumping off point. Additional Soviet aircraft had also appeared over the combat zone, engaging the Japanese in fierce struggles for air supremacy.

The Japanese commanders now realized they were indeed in an untenable position, with their forces divided on both sides of the river and with a more powerful than imagined enemy force between them. The Japanese commander realized his forces had no additional bridge-building materials on hand, making it imperative that his forces west of the Halha be withdrawn immediately. Most of the forces made it back north and across the Halha that night and reestablished themselves by the morning of July 4 on the Fui Heights. The covering Japanese unit managed to make the crossing the following night before destroying the pontoon bridge.

The Kwantung Army made the fateful decision to pull its two tank regiments from the combat zone. The Soviets had actually suffered heavier tank losses, but they had begun with a significant numerical advantage in armor and were able to continue delivering improved tanks to the battlefield.

Lessons of the First Battles

In both the May 28 and the early June battles, the Japanese lacked sufficient military intelligence, and they had seriously underestimated the enemy’s strength and determination. Hubris and their racist sense of inherent superiority over the Soviets and their MPR allies played a role as well. Most could not contemplate the idea that Soviet firepower could overcome the Japanese fighting spirit. The events also gave the Soviets reason to pause. The movement of some 10,000 enemy troops over the Halha River had gone undetected despite heightened awareness, and the Soviets might have been able to pin and destroy the units west of the Halha had they moved faster.

Zhukov was no fool. In fact, he proved to be a quick learner throughout his career. In those two days at Nomonhan, Zhukov learned to use large tank formations as an independent attack force, rather than simply as support for infantry. This was far different from conventional views, and the concept would be proven again and on a much larger scale by the German panzer divisions early in World War II. The Soviets had learned the importance of hatch covers that could be locked from the inside, frustrating enemy infantry attempts to put tanks out of commission by opening the hatches. They also found that gasoline-powered tanks, with their exposed ventilation grills and exhaust manifolds, could be easily set afire. The combat at Bain Tsagan clearly showed the importance of overwhelming force and close integration of tanks, motorized infantry, artillery, and air power in defeating an enemy. The need for improved aerial reconnaissance was also apparent. These were important lessons for Zhukov and the Red Army as World War II loomed.

An 800-Mile Supply Loop

Moscow now agreed to send additional reinforcements to Zhukov. Thousands of men and machines were sent east, requiring additional trucks and transports to shuttle the men and equipment from the railhead at Borzya to the front lines. The effort resulted in a continuous 800-mile, five-day, round-trip shuttle that put both men and machines to the test.

The Soviets by now had managed to build seven bridges across the Halha and Holsten Rivers to support their operations, including one invisible bridge built with its surface some 10-12 inches below the water level so it would not be seen by Japanese pilots. Between July 8-12, Japanese probing continued making gradual progress against the Soviets although they suffered substantial losses to superior Soviet artillery. The fighting became especially fierce in the early morning hours of July 12 as the Japanese forces pushed to within 1,500 yards of the primary Soviet bridgehead over the Halha. As the day wore on, Soviet counterattacks with two infantry battalions and some 150 armored vehicles coupled with strong artillery support managed to push the Japanese back to their starting point. The Soviet artillery especially had taken its toll and the Japanese decided to suspend their night attacks that had resulted in 85 deaths and three times that in wounded personnel in one regiment alone.

The officers of the Kwantung Army were determined to save face and push the invaders back to the west side of the Halha. Other divisions were stripped of their heavy artillery, and the 3rd Heavy Field Artillery Brigade was shipped from Japan to Nomonhan. That brigade came equipped with 16 relatively modern 150mm howitzers and 16 100mm artillery pieces, all pulled by tractors rather than horses like the artillery in the 23rd Division. Army officials hoped to mount a large-scale artillery duel, force the enemy back to the west bank, and then withdraw after saving face.

The Soviets were not standing pat, and reinforcements and supplies continued to pour into Zhukov’s First Army Group, including two additional artillery regiments and literally tons of artillery shells.

Looking For Conflict Resolution

The Japanese fired the next salvos in the conflict with a sustained barrage on July 23. The Soviets rose to the challenge, with artillery rounds falling on the Japanese positions from artillery located on both sides of the Halha. The Soviets wrested air supremacy from the Japanese, their fighters strafing enemy positions and shooting down two Japanese balloons used for artillery spotting. The intense artillery duel went on for two days with the Soviets demonstrating that they had plentiful ammunition, better artillery, and more of it. The heavy Soviet guns were deployed out of range of the Japanese guns, and the Russian 152mm artillery was deadly beyond 15,000 yards.

The Kwantung Army ended its ill-fated artillery attack on July 25, and the general staff in Tokyo began pursuing a diplomatic resolution. That, in turn, irritated the Kwantung Army, which wanted to fight on to save face. The army’s General Isogai was called to Tokyo and told point blank that the Kwantung Army was to maintain its defensive position east of the Soviet positions while the government worked to resolve matters through diplomacy.

Amazingly, the Kwantung Army chose to ignore the directive, but it was the Soviets under Zhukov who were to take the next step, based in part on events in both the West and the East. German demands on Poland were heating things up in the West, and both the Germans and the British were attempting to obtain an alliance with the Soviets. In addition, Richard Sorge, the Soviet super spy in Japan, confirmed that the Japanese high command wanted a diplomatic resolution to the problems at Nomonhan.

In light of these developments, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin decided to order massive combat operations against the Japanese. Zhukov’s First Army Group was further strengthened by two infantry divisions, the 6th Tank Brigade, 212th Airborne Brigade, additional smaller units, and two Mongolian cavalry divisions. Zhukov’s air support also was considerably strengthened. The Japanese remained unaware of the additional buildup. They had only one and a half divisions in place.

Zhukov’s Maskirovka

Zhukov kept up his aerial reconnaissance and scouting efforts to gather information on the opposing forces. He planned to lead his central force in a frontal assault against the main Japanese positions several miles east of the Halha. Zhukov’s northern and southern forces—with the bulk of the Soviet armor—would turn the enemy’s flanks, creating an envelopment of the Japanese. Overwhelming force and tactical surprise would be keys to the plan.

During World War II the Soviets were to become masters of maskirovka—or military deception—but Zhukov was to prove his near mastery of the concept even at this early stage. Trucks carrying men and matériel on the long journey from the staging area at Tamsag Bulak traveled only at night with their vehicles’ lights blacked out. Aware that the Japanese were tapping their telephone lines and intercepting their radio messages, the Soviets sent a series of easily deciphered messages concerning the building of defensive positions and preparations for a long winter campaign. Well before the attack, the Soviets nightly broadcasted the recorded sounds of tank and aircraft engines along with construction sounds. The Japanese became accustomed to the broadcasts and were unconcerned by the actual noise as the Soviets moved their tanks and equipment into position on the night of the attack.

Zhukov cleverly directed a series of minor attacks on August 7-8 to expand his bridgehead east of the Halha by some three miles. He made sure these were contained by the Kwantung Army, further lulling the enemy into believing that the Soviets were relatively weak and poorly led. Under the cover of darkness on the night of August 19-20, the major force of his First Army Group crossed to the east bank of the Halha into the expanded Soviet enclave. Massive amounts of artillery on both sides of the river were available to support the assault.

Stalin’s Offensive Begins

The attack began with Soviet bombers pounding the Japanese lines just before 6 am on August 20, followed by nearly three full hours of heavy artillery fire before the bombers attacked again. “The shock and vibration of incoming bombs and artillery rounds” caused Japanese “radio-telegraph keys to chatter so uncontrollably that the frontline troops could not communicate with the rear, compounding their confusion and helplessness,” reported one observer.

At 9 am, Soviet infantry and armor began moving forward with artillery supporting their efforts. An early morning fog along the river assisted the advancing troops, and the damaged communications lines prevented the Japanese artillery from participating until a bit after 10 am when many of the forward positions had already been overrun. Japanese resistance had stiffened by noon, and combat raged over a 40-mile front. The southern Soviet force, consisting of MPR Cavalry, armor, and mechanized infantry, pushed the southern Japanese force northward and inward by eight miles during the first day’s fighting. The northern Soviet force, consisting of two MPR cavalry units, supporting armor, and mechanized infantry, pushed the northern flank back two miles to the Fui Heights. Zhukov’s central force pushed some 750 yards forward against resistance so fierce that the Japanese dared not move troops to reinforce the flanks.

Over the next two days, the southern Soviet force broke through the Japanese lines and then proceeded to encircle and eliminate the enemy in small pockets. Once the heavy Japanese weapons were eliminated, Soviet artillery and armor tightened the ring further with flame-throwing tanks and infantry. By August 23, the southern thrust had reached Nomonhan where it could block a possible Japanese retreat.

Japanese airpower tangled with Soviet planes, which had a two to one advantage. The Soviets had recently brought forward updated I-16 fighter planes with thicker armor plating and a strengthened windshield that could withstand the 7.7mm machine-gun fire of the Japanese Type-97 fighters. The Japanese upgunned some of their planes, but this was quickly offset once the Soviets discovered that the enemy’s fighters had unprotected fuel tanks and began filling the sky with burning Japanese planes.

Eliminating the Remaining Pockets of Japanese Resistance

On the night of August 22, the Japanese planned a counterattack against the Soviet forces that were crushing their southern flank. The 26th and 28th Regiments of the 7th Division and the 71st and 72nd Regiments were pressed into action. Only the 28th was at full strength, although its men had marched 25 miles to the front just a day earlier. The units were deployed on the night of August 23, and many units did not reach their assigned positions by the next morning. Those that did arrive scurried into position before fully reconnoitering the enemy positions.

Using the early morning fog to mask its movements on August 24, the 72nd Regiment made for a distant stand of scrub pines only to discover rather late in the going that the pines consisted of a well-camouflaged force of Soviet tanks. The Japanese, in fact, had stumbled into a massive Soviet tank force equipped with prototype models of the superb T-34 tank with its high-velocity 76mm gun and thick sloping armor. Later models of that versatile and well-designed tank were to cause nightmares for Nazi forces in World War II. The Soviets also had updated models of the BT-7 tanks, which were now equipped with diesel rather than gasoline engines and had protection over grills and exhaust manifolds to help protect them from Japanese fire.

The attacking Japanese southern force suffered nearly 50 percent casualties and was ordered to withdraw shortly after sunset. The Japanese forces on the northern end of the line at Fui Heights had sustained three days of hammering by the Soviets, but the 800 well-entrenched men inflicted heavy losses on the advancing Soviets while disrupting Zhukov’s time table for the entire operation.

The ambitious Zhukov was not pleased. He got on the horn, fired the commander of the northern force, and then fired his replacement as well before sending up a member of his own staff to lead the faltering force. That night a renewed Soviet attack led by flame-throwing tanks and supported by heavy artillery managed to quash the remaining Japanese artillery on the heights. Supplies of ammunition and food were cut off as the encircling Soviets tightened the ring over the next two days. On the night of August 24-25, the remaining Japanese withdrew from Fui Heights without orders. The Soviets counted more than 600 Japanese bodies when they occupied the heights the next morning.

Zhukov’s northern force moved on, pushing south and east toward Nomonhan. Within a day the northern and southern forces had linked up near Nomonhan. The encircled Japanese fought on, with many of their howitzers seizing up from heated overuse. The artillery units were destroyed by tank and heavy artillery fire or overrun by Soviet forces. By August 27, a Japanese relief force of two infantry regiments and an artillery regiment reached the northeast portion of the Soviet ring. The 5,000-man force could not break through, and it retired four miles east of the Soviet-claimed border at Nomonhan. Over the course of the next two days, Soviet planes, artillery, and armor continued to destroy remaining pockets of Japanese resistance within the solid ring created by Zhukov’s forces. A few hundred lucky Japanese managed to escape to relative safety east of Nomonhan.

Resolving the Japanese-Soviet Border War

Zhukov declared the disputed territory to be enemy free on August 31. The fighting had been the worst modern Japanese defeat up to that time with the Sixth Army losing between 18,000 and 23,000 men killed or wounded between May and September. The Kwantung Army lost nearly 150 aircraft and many of its tanks and artillery. The Soviets lost more than 25,600 killed or wounded according to a fairly recent Russian report. While the Soviets suffered more deaths and injuries, their repeated overpowering attacks forced the enemy from the field.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, signed on August 23, 1939, also helped to weaken the hawks in the Kwantung Army. Close military cooperation with the Germans against the Soviets—as the militants had long advocated—was no longer a realistic possibility. Following the disaster at Nomonhan, the Kwantung Army had submitted an aggressive plan for an escalation of the war, but authorities in Tokyo were determined to finally bring the Kwantung Army under control. General Nakajima of the headquarters staff flew from Tokyo to direct the Japanese forces to hold their positions and to ensure a quick, diplomatic resolution. Once on the ground, he was unbelievably swayed by the Kwantung Army’s arguments and had to be sent back again by Tokyo to convince the Kwantung Army that enough was enough. The imperial order was to be obeyed. General headquarters then cleaned house, relieving some of the Kwantung command and transferring other officers so that diplomatic efforts could move forward.

While the world was focused on the September 1, 1939, German invasion of Poland, the Japanese and the Soviets quietly worked on an agreement signed September 15. Both sides recognized their troop positions as the temporary border. It approximated the earlier Soviet-MPR border claim with a joint commission to later formalize the boundary. Prisoners were exchanged and both the new Kwantung Army leaders and the Red Army leaders closely followed the agreement, bringing the war to a close.

Stalin waited until the agreement was concluded, and then on September 17—when he was sure he did not face the prospect of a two-front war—sent the Red Army across the Polish border per his earlier agreement with Hitler on the partition of Poland.

The Remarkable Strategic Impact of the Nomonhan Incident

The Nomonhan Incident provided quite a learning curve for all involved. The Japanese came away with a black eye and a healthy respect for the Soviet military, which many in the international community had viewed as weak and lethargic in the wake of Stalin’s extensive purges. Japanese attention was turned southward toward the oil-rich East Indies and subsequently to the only major force that might hamper Japan’s expansionistic plans—the U.S. Navy and its base at Pearl Harbor. Japanese officials knew that U.S. industrial strength was much greater than the Soviet Union’s, and it superseded Japan’s strength by a factor of 10 to one. Japanese militants believed that a surprise attack would provide time for the Japanese to seize the resource-rich areas to the south and then build a strong defensive perimeter enabling them to negotiate a settlement with an America focused primarily on Europe.

The Japanese elected to move southward, rebuffing German overtures to strike the Soviet Union in the Far East as the war progressed. Maj. Gen. Eugene Ort, the German ambassador to Japan, reported in late 1941 that Nomonhan had left a lasting impression on the Japanese, who “considered participation in the war against the Soviet Union too risky and too unprofitable.”

Soviet master spy Richard Sorge remained active in Tokyo. Later, his reliable reports assured Stalin that he could safely transport thousands of Siberian troops westward to deal with the German onslaught after the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, especially around Moscow and later Stalingrad. Zhukov and the winter-hardened Siberian troops used the combined arms tactics and maskirovka (deception) that had proven so successful at Nomonhan, but on a much larger scale with much more at stake.

Could the Soviet Union Have Fought a Two-Front War?

The Soviet archives have been opened in recent years, and many military analysts now assert that the Soviet Union simply could not have survived a two-front war. Even in 1941, Maj. Gen. Arkady Kozakovtsev, then head of the Red Army in the Far East, reported quietly to a trusted confidant that the Soviet cause was hopeless “if the Japanese enter the war [against the Soviet Union] on Hitler’s side.”

The Soviet Union, in fact, was the only major power in World War II that did not have to contend with an energy-draining and resource-depleting two-front war. The early success at Nomonhan meant the Soviets could later focus solely on the Nazis at the front gate, using the hard-fought lessons learned in the East to help the Allies subdue and defeat Nazi Germany.

The most consequential battle that almost nobody in the West has ever heard of.

Arguably WW2 could have ended with a totally different result had this relatively minor engagement gone the other way and the Japanese headed North rather than South toward Pearl Harbor as subsequently played out.