By Alan Waite

Following the occupation of a defeated Nazi Germany, the victorious Allies initiated a prearranged plan for prosecuting captured Axis officials for war crimes. Throughout Europe, British, French, Soviet, and American military courts, along with various civilian courts and high-level Allied tribunals, tried hundreds of Axis leaders and underlings. Scores were executed and hundreds imprisoned. Few were exonerated or released, at least in the initial postwar years from 1946 to 1947.

After the trial of the major Nazi leaders under a multinational tribunal at Nuremberg (the IMT or International Military Tribunal Case) in 1945-1946, the Americans tried dozens of second-level officials in a series of 12 trials. The law authorizing these trials was known as Control Council Law No. 10 (CCL10). The 11th of the CCL10 trials to be organized but last to conclude was the so-called Wilhelmstrasse or Ministries Case (U.S. vs. Ernst Von Weizsacker, et. al., 1947-49).

In the early 1980s while completing a graduate degree, I wrote a thesis on the leniency given defendants in the Ministries Case. My research led to a brief correspondence with Hitler’s architect and Reich Minister for War Production, Nuremberg defendant and author Albert Speer, along with dozens of interviews with Holocaust survivors, former Nazi Party members, former members of the SS, and ultimately a former Ministries Case prosecutor, Alvin Landis.

I spoke with Landis on two occasions, once in 1981 and again in 1983 for a combined total of 71/2 hours, resulting in nearly 100 pages of transcription. The bulk of the interviews dealt with the intricacies of the Ministries Case and controversies that had dogged the Nuremberg Trials over the years, controversies that in some areas continue today. However, some of the discussions covered topics of general historical interest, creating a fascinating picture of the time and place and the people who fought for justice, as well as those who sought to avoid it.

AW: What’s your life story before joining the prosecution at Nuremberg?

Landis: We are Russian Jews, my family that is. I was born in Kiev, Russia (Ukraine), in 1907. My father, Oskar, immigrated to Chicago alone that same year, then sent for our family in 1909. He sold coal from a horse and wagon until he could afford to open a small clothing business. I had six brothers and sisters, and growing up in Chicago in the early part of this [20th] century toughened you up. It was in the 1920s that I acquired my progressive social and political views, which eventually led me to the Lewis Institute and the University of Chicago, and from there to the University of Illinois Law School, where I took my LLD in 1930.

The City of Chicago was looking for prosecutors in 1930, so I applied and got hired and worked in the D.A.’s office until 1933, when I became city corporate counsel. In 1937, I became assistant attorney general for Illinois and was part of the team that took down Al Capone and his mob, which gave me a small reputation in the law enforcement world…. During the war [World War II] I moved to D.C. upon my appointment as regional counsel for the U.S. Bureau of Mines, and in 1945, I took a position in the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Solicitor‘s Office.

AW: How did you end up as a prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials?

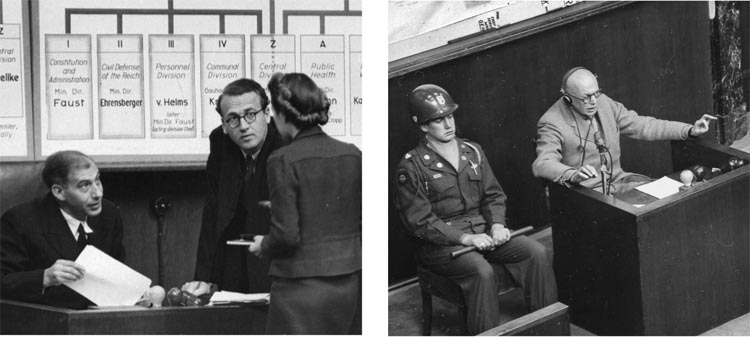

Landis: Well, when I was with the Solicitor’s Office, I shared an office with Paul Gantt, an Austrian by birth and a real up-and-comer who was selected by Brig. Gen. Telford Taylor to join one of the prosecuting teams for the 12 CCL10 trials held by the United States after the big IMT (International Military Tribunal) deal was over. Taylor had become chief prosecutor for those trials—he replaced Bob Jackson, who’d handled the IMT case—and Taylor liked Gantt because Paul had a great reputation as a lawyer, spoke German, and hated what the Nazis did to Austria. Both men were young, in their 30s, and took a liking to each other right away.

When Taylor hired Gantt, he asked, “Know any other good lawyers back in the States with criminal prosecution experience?” Gantt knew about my experience in nailing Capone and his gang back in my Chicago days, so he gave Taylor my name. I found out later Paul said to Taylor, “By the way, Landis is Jewish,” and Taylor said, “I don’t care if he believes in Santa Claus. Is he a good lawyer?” You see, being Jewish in America in those days was not always easy. You got hassled at times and excluded from groups and clubs and such, but I never forgot what Taylor said.

AW: Was your Jewish faith brought up at all in the hiring process?

Landis: Not by the Army, but I told the colonel who first called me and he said, “So what? Military cemeteries in Europe are filled with Jews—soldiers and pilots—buried right next to Christians.”

AW: Did it matter to you?

Landis: Well, above everything else I’m an American, and Americans don’t go in for things like Nazism and genocide. Did we lose relatives in the war? You bet, and it sure as hell didn’t make me love ‘em [the defendants], but being Jewish never came up while I was over there.

AW: So who contacted you?

Landis: Some Army colonel called and left a message with my wife, and when I got home she looked really worried and told me, “Alvin, the Army called for you.” I said, “What the hell for? I’m over age and the war is over?” So the next day I called back, and the officer said, “Mr. Landis, General Taylor has asked personally if you will join the prosecuting team at the Nuremberg trials … you would be in Germany for approximately one year but you can’t bring your family. Your experience and skills are just what we need.” I told him I needed to think it over and talked with my wife that night, and we decided in the end that I had to answer my country’s call … plus we knew I would be a part of a rare moment in world history, so I agreed to go. I left for Germany in July 1947.

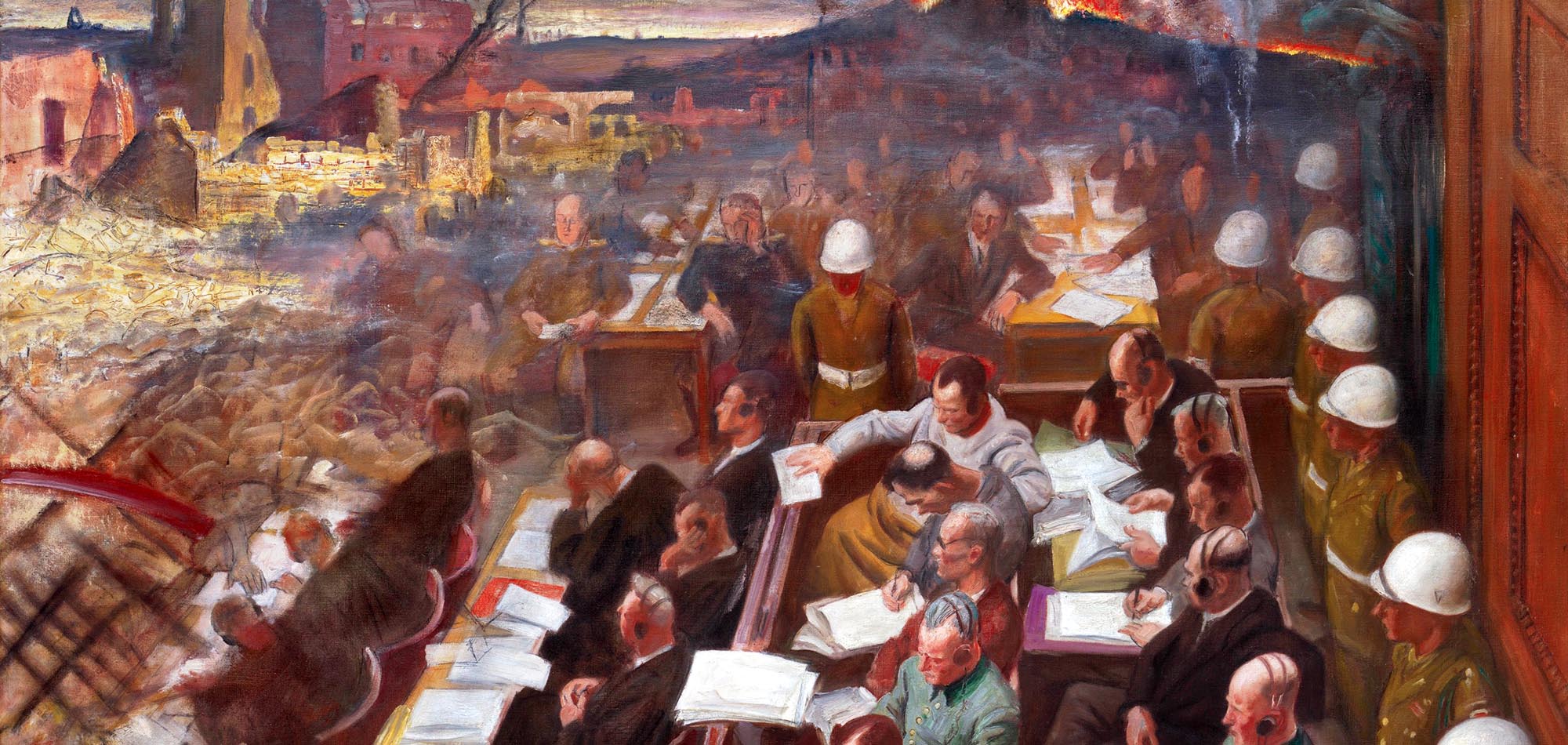

AW: What was it like when you first set foot in Nuremberg?

Landis: The trials were held at the Palace of Justice … most of it had survived the bombs but the city was still in ruins—just piles and piles of bricks and burned out walls. Hundreds of Germans were still buried in those ruins, and dozens of remains were being hauled out of the debris each week. The taxis and streetcars were running, and the Old City walls were mostly in place—and we were surprised at how almost all of the Nazi Party rally grounds were untouched … just outside the city. The Zeppelin field was impressive—the arena where they had the searchlights all around the rim pointing straight up into the sky … those fellows knew how to control their people.

Now, there was no heating and no cooling, and our offices were either too cold or too hot. A lot of our people stayed with local Germans, but some of us stayed in the Grand Hotel, which the Army rebuilt for the trials in 1945-1946 to the tune of over a million bucks. This was the hotel where Hitler stayed when he attended the Nuremberg Party rallies.

We were short of office supplies—couldn’t find paper clips and staples, for example. During the entire year I was there I had milk once—it was rationed for German women with babies and small kids or Americans who’d brought their families over. But the ration for whiskey was a case a month, and you could get all the wine and beer you wanted … which led to some interesting pretrial conferences.

You could get about 20 German marks for a buck, but few Germans wanted marks, just American dollars or even more valuable cartons of cigarettes. Cigarettes were the real currency at that time. With American cigarettes, you could get anything that you wanted, from food to anything else. One carton, for example, might get you merchandise priced at say, 500 or 600 marks.

AW: Nuremberg was the “spiritual home” of Nazism, and most residents supported Hitler fanatically. How did the place feel while you were there?

Landis: You mean the people? How they felt about Hitler? Mostly the Germans would not talk to us or look us in the eye unless they had to … they were a conquered people and acted like it, and no one talked about Hitler one way or the other; they were afraid. The only one I remember saying anything about Hitler was a former party member who cleaned our rooms each day. One day I asked him why he joined the [Nazi] party, and he said, “We had to or we couldn’t work here.” He was probably right about that, considering Nuremberg was “Hitler’s Vatican.”

AW: Vatican?

Landis: The religious center of the Nazi Party …

AW: How did the Germans treat you?

Landis: That is very interesting. Overall, I was treated well, now and then smiles and pleasant nods, but mostly just ignored as if we weren’t even there. Remember, those people had been reduced to poverty and mostly were just trying to stay alive one more day. You saw old women pushing carts full of wood and kids picking through bombed-out buildings that hadn’t been cleared yet. Some even scooped up horse droppings to use for heating and fuel. You can’t imagine what they were reduced to even two years after the end of the war.

You know, I don’t think I saw one fat German in Nuremberg, too many years of not having enough good food. They were all skinny and hollow looking—wearing old clothes, a lot of them torn or sewn up several times. These people were still a world apart from us. The Germans at the Grand Hotel treated us like conquerors … ja bitte this and ja bitte that … but you couldn’t read them at all, whether they were angry or just detached. Now, if the topic of the trials came up and you were talking with a German in the hotel, they would just clam up and the conversation would end, except for that one fellow.

Ironically, some of the men we saw cleaning up the debris were former Nazi officials—the little fish who didn’t pull off big crimes but ran the show for Hitler at the local level…. These guys had been sent before German de-Nazification courts, if you want to call them courts, and sentenced to labor service cleaning up Germany…. For example, one fellow outside the Palace of Justice who had clerked in the local Nazi Party offices was sentenced to six months, five days a week, and eight hours a day clean-up duties by a de-Nazification court … some justice in that I imagine.

AW: Your courts, however, handled the top officials of the German nation?

Landis: Right, the big shots—Hitler’s lieutenants. We had 12 trials. The Brits, French, and the Russians … well … who really knows how many? I can’t remember them all offhand, but we tried the doctors, the industrialists, the Army high command, the SS mobile killing squads, the judges, the guys at the top. At the same time, military courts tried the small-fry criminals,the guys who worked in the concentration camps, or the guys who murdered downed pilots, or the ones who massacred unarmed civilians. The lower level defendants had military trials and military judges. Things generally did not go well for them in those circumstances.

AW: How soon did you start work?

Landis: Right away. There was a stack of casebooks from prior Nuremberg trials to go through, and briefings, staff meetings, and mountains of evidence to read. Our team was divided up, and we were individually assigned to three or four defendants for prosecution. There were 16 [defendants] altogether. Generally, if we wanted something we got it, though getting requests fulfilled by the Army was at times like sprinting through snow drifts.

AW: Which defendants did you prosecute?

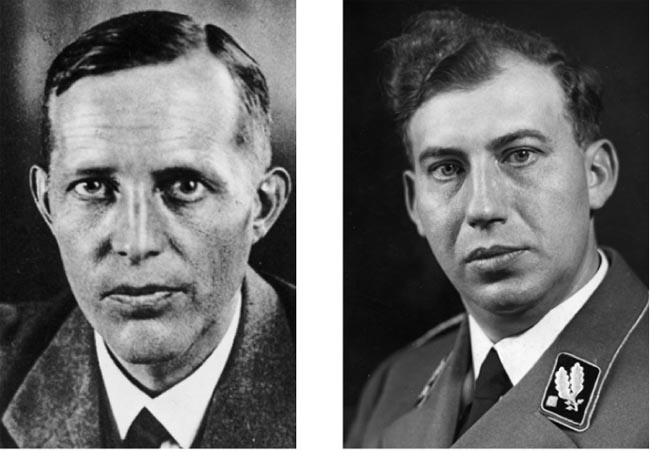

Landis: Von Krosigk [Lutz Graf Schwerin Von Krosigk, Reich Minister of Finance 1932-1945, Reich Chancellor May 1-23 1945], Stuckart [Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart, Interior Ministry State Secretary], and Lammers [Hans Lammers, Chief of the Reich Chancellery].

AW: Why was your trial called the Wilhelmstrasse or Ministries Case?

Landis: Because we tried the state secretaries of the major German ministries—the guys who were the real heads of the Nazi government. The fellas who drafted most of the orders and decrees, based on what their bosses told them, then saw that they were carried out. Most of their ministries were located on the Wilhelmstrasse, the street that was the seat of the German government, where Hitler’s Reich Chancellery was located. So you had guys like Stuckart in the dock instead of his boss, Himmler or Dietrich [Otto Dietrich, Reich press chief] instead of Goebbels, or Lammers instead of Bormann. Without these officials, nothing Hitler ordered could have happened. It required full cooperation from their ministries, and these guys made sure it happened the way “Der Fuhrer” ordered.

AW: Where was the Ministries Case trial held?

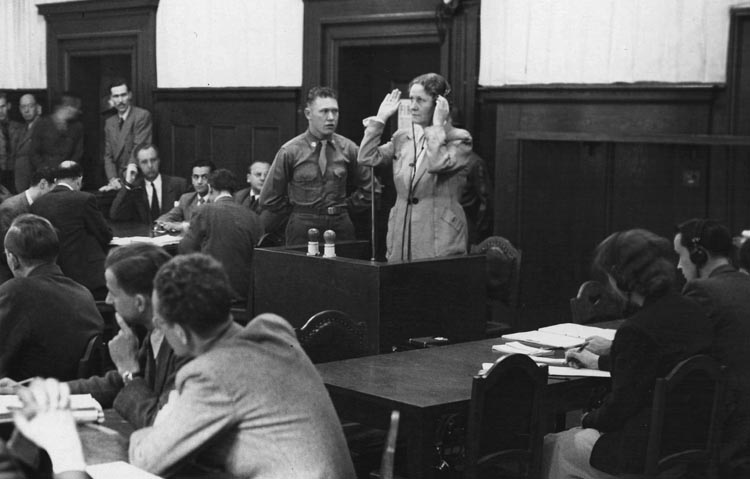

Landis: Interestingly enough, our trial was in the same courtroom as the IMT trial—where the big bosses like Göring and Hess were tried. I hoped to be able to see some of the big names from the IMT trial, Hess and Speer and Dönitz, but they were all moved to Spandau Prison in Berlin before I visited the Nuremberg prison. There were still some interesting prisoners there, though, in the prison right behind the Palace of Justice, like Hitler’s personal secretary, Wolfe [Joanna Wolfe—who remained a defiantly unrepentant Hitler apologist].

AW: Did each defendant have competent counsel?

Landis: Absolutely—and impressive too. Those guys were on top of their game and had a great network that always knew what we were up to.

Once I went to a small town and picked up a witness we discovered who had good information about Stuckart’s complicity in crimes against humanity. So I picked him up at midnight and had him in our witness safe house by 3 am. I go to the courthouse at 8:30 am, and Stuckart’s attorney comes up to me and says, “I understand that you brought in a new witness. When can I talk to him?” I say, “I’m not certain exactly who you mean?” He smiles and says, “No, of course not. Let me help you.”

He proceeds to tell me, “His name is so-and-so, he is a lawyer and he has brown hair and blue eyes, was taken into your custody at such-and-such strasse in Aschaffenberg, and is wearing such-and-such pants and shirt with a gray sweater. He is still asleep at the moment, I understand. Does that help, Herr Landis?” That’s how good they were.

AW: Did you think people on your team were leaking information?

Landis: Our team? Hell no. Someone somewhere down the chain. We were a need-to-know operation but very little was confidential on so big a prosecution.

AW: How well did the translation process during the trial work?

Landis: Like a top. We had some problems when people talked too fast, but those translators, I think we had four of them working at one time, were the best. A German witness would be asked a question in English, say, and he’d answer in German, and before he was finished the translation was in our headsets. And as soon as he stopped, the translator had caught up.

AW: What was the presiding judge like?

Landis: Christianson [William C. Christianson]? Nice man but sort of a weakling—not as strong as we’d hoped. Came from the Minnesota Supreme Court and had been on one of the earlier Nuremberg tribunals but not as presiding judge [Industrialists Case]. Seemed more concerned about the defendants’ rights, we thought, than what those guys had actually done. But he knew the law and was fair to both sides, no doubt about that.

AW: How about your prosecuting team? Who was the toughest?

Landis: That would be Bob Kempner, a great and gutsy guy who was a German who had joined our prosecuting team. Before Hitler came to power Bob had openly opposed the Nazi Party and nearly paid for it with his life. He had two doctoral degrees and was so proud about it that you could not call him “Dr. Kempner,” you had to call him “Dr. Dr. Kempner.” The German people were tired of the trials by the time ours started in 1947, and Bob took a lot of heat—even threats—but he worked all the harder. After what his country had been through, he believed that the rule of law was its only hope for the future, and his example inspired us all.

AW: How did the defendants behave during the trial?

Landis: For the most part, they all just sat there and listened. It was nothing like the movie Judgment at Nuremberg. Nothing like that at all; a complete distortion … lawyers raising hell with the tribunal, defendants acting up like that. You couldn’t even raise your voice or they came down on you like a ton of bricks. It was all according to military discipline and formal right down the line. Even when the tribunal read the sentences the defendants just stood there and stared, didn’t react at all. I watched every one of them.

Same with the German defense attorneys. You could not tell at all what they thought about the things their clients did, if they approved or disapproved. They were mechanical, almost expressionless. For that matter, the German people showed no reaction during the trial either. They filled the courtroom most of the time, but they just sat there and stared no matter what crime or atrocity was being shown. Never a word, just sat in silence. I never understood any of that.

AW: Of all the defendants in your dock, who was the most interesting?

Landis: Schellenberg [Walter Schellenberg, SS General and Chief of the SD Foreign Intelligence Service], no question. Paul Gantt prosecuted him. We used to talk a lot about how slippery this fellow was. Schellenberg was likable, smooth, and very sharp, very handsome and personable and a skilled master spy, like the guy in the spy movies, what’s his name? The Bond character? James Bond. Only Schellenberg was the one in charge and always one step ahead of everybody. He had a string of girlfriends stashed all over Europe, even the big French perfume maker, hmmm, who was she? Right, Coco Chanel. Schellenberg arranged the famous kidnapping of those British officers in Holland in 1939—the Venlo Affair—and he personally tried to bring the Duke and Duchess of Windsor to Germany from Portugal in, what, 1940? He managed to play all sides, and he survived when everyone else in the SS at his level either killed themselves or were hanged; he even talked Himmler into trying to work out a separate deal with the Allies at the end of the war. That guy was one cool customer.

AW: Was he a convinced Nazi?

Landis: Said he wasn’t political or anti-Semitic, but the evidence proved the opposite, the letters and memos he wrote, and his interviews right after he was arrested. Yeah, he was a Nazi like the rest, or at least he played the part up and until the Third Reich was collapsing, then surprise! He was working secretly against Hitler all along! You cannot imagine how many of these guys made the same claim. Makes you wonder how, with so many high-level officials all secretly working against Hitler, just how the Nazis were able to do what they did.

AW: How would you describe Schellenberg using just one word?

Landis: Dangerous. Complicated. Two words.

AW: Who did you most want to convict? Schellenberg?

Landis: Nope. All of ‘em. The whole damn bunch. They were all involved in war crimes and crimes against humanity, and they knew exactly what they were doing. They did it either because they thought they were saving the world or just for themselves, for the money, the power, and the spoils of war.

AW: But if you had to choose just one defendant?

Landis: Well, if I had to choose one above the rest… Yeah, no question, it was Stuckart.

AW: Why him?

Landis: Because that fine fellow was there when the whole Final Solution was planned. He sat in that conference on Wannsee Lake in January 1941, when Heydrich and his SS boys told all of the ministry officials what they were about to do and how they would do it—arrests, trains to Poland, the gassings, working the rest of ‘em to death. [Heydrich] laid out the whole plan, and Stuckart sat there and listened, then tried to tie a string around the definition of who was going to die and who wasn’t—who was and wasn’t a Jew.

Geez, he [Stuckart] was the guy who wrote the Nuremberg Laws, the laws that stripped Jews of their professions, property, and citizenship—and then he claims at his trial that he was working against Hitler trying to save lives. The man was a lawyer for crying out loud.

AW: So what was the basic line of defense?

Landis: The litany of excuses …“I didn’t know it [“it” refers to the torture, medical experimentation, murder, mass executions, and gassing of innocents] was going on, and if I did, I didn’t know it was wrong—if I did, I didn’t issue the orders. If I did [issue the orders], the translation isn’t accurate. If it is [accurate] I was actually trying to limit the extent of the damage.” Documents weren’t a problem either, explained away with even more excuses. “If it was written to me, I didn’t see it. If my initials were on it, it was my subordinate [who] initialed it on my behalf. If I signed it, I didn’t read it, and if I did read it I didn’t understand it—and the excuse most used—what could I do, I was just following orders?” But that whole line of baloney collapsed under the weight of the paper.

AW: What do you mean?

Landis: The Nazis were great record keepers. Everything they did they documented, probably to cover their rear ends—authority was everything in the Third Reich, and you were always under suspicion or being challenged or set up for a fall. Anyway, there were tons and tons of documents to choose from. Most of the mountans of documents had already been translated and used in other war crimes trials cases. Our problem was one of riches. We had to sift through and use the most damning documents to build our case. Only problem was, even then it was not always crystal clear to the judges how much guilt to assign to individual defendants because we were plowing new ground here.

AW: How so?

Landis: Well, let me explain it this way. You had a governmental complex with competing ministries and intentionally overlapping authorities. Hitler wanted it that way so no one became too powerful and could challenge his position. So, say Lammers, who was vice chancellor, and Göring and some other muck-a-mucks in the Army get together and say, “We want all the wheat and corn from this part of the Ukraine to feed the troops fighting nearby.” So Darré [Richard Darré, Reich Minister for Agriculture] is given the job by Göring, and he turns to the SS who run the police, and they go in and take the wheat and corn using Ukrainian collaborators. In the process, hundreds of farmers who protest are shot, and some small towns are destroyed. Now you have war crimes and crimes against humanity.

So the Russians prosecute the Ukrainians and the SS guys they captured, and we go after Göring and Lammers and Darré, but just who is really responsible? Göring? Darré? The Army high command? The SS? How far does guilt extend? Who should hang? Who should go to prison? Göring issued the orders, but the Army asked him to. Lammers was involved to provide Hitler’s authority, but he personally didn’t have a stake in the action, see? Darré passed the orders on, but he didn’t know the SS and Ukrainians would slaughter those farmers, right? The Ukrainians killed the farmers, but only because the farmers tried to stop the process. What is legal? What is illegal if you are occupied by another country? Did you know, for example, that it is perfectly legal under international law to take hostages and shoot them as reprisal against attacks on your occupying troops? It has to be done a certain way, which the Germans always ignored, but it is legal if done right.

So who is truly guilty? Everyone? Pick your trial. There were different opinions among the justices. In the early trials, very few guys got around long prison terms or execution. By the time our trial was over, it was the other way around.

AW: Which takes us back to Stuckart. Why did he get off with basically time served?

Landis: It was political … political. Most likely he’d have hanged in 1946, but he was out of prison in 1950. It was political.

AW: How so?

Landis: By 1949, when our trial finished, the Cold War was a hot war, and Germany was ground zero. After they’d killed the ones they wanted, the Russians threw away the rope to influence German public opinion, which had turned against the trials.

We became the bad guys because we were still trying their leaders, you know, the judges and industrialists and ministers, and sending them to prison. Stalin found that if they let up on the important ones they had in Russian custody, those Germans—scientists, financiers, administrators, and the like, all smart cookies—would join the Communist Party and work very ardently for old Papa Joe as long as their lives and properties were restored.

AW: Did your team think that pressure was put on your tribunal to go lightly on Nuremberg defendants?

Landis: Absolutely. We didn’t know who specifically applied the pressure, but we knew it had happened, and the sentencing bore that out. We had these guys dead to rights, but if Stuckart was going to get a light sentence, you can imagine what happened to the rest of them.

Some researchers write about how a few of the justices in the U.S. Nuremberg trials privately held anti-Semitic views, which might have led them to err on the side of lenient sentencing.

If that happened, we never knew about it, and I am Jewish so I would have said something. Some justices seemed to disagree with the IMT ruling that “just following orders” could not mitigate a defendant’s guilt. I know of one or two who thought that these guys had to follow orders or be executed, so what choice did they have, right? But that was rarely the case. If you didn’t play ball the Nazi way, you might lose your job and be black balled, but the defense never proved that anyone was shot for refusing a criminal order.

In fact, we were able to show cases where people who refused an order were not shot or put in prison. One case I remember was this fellow Graf, who was an SS sergeant who was asked to command a killing squad in Russia and refused—and he was arrested, then sent back to Germany and reassigned. No, no, no, it was politics, pure and simple. I remember one [U.S] Army captain told us one day that if the Russians wanted to take Germany, they could bust through to the French coast in three or four days. There was nothing there to stop them, not enough troops, tanks, or planes, just the [atomic] bomb. We needed the Germans and Germany to stop the Soviets, and so the word came down, “No more life sentences and no more rope.”

AW: What did that feel like to you?

Landis: Do you think mass murderers should get the death penalty? You do? Well, how would it feel if you put a year of your life into prosecuting several mass murderers who were up to their necks in the deaths of millions of people, and they got a slap on the wrist?

AW: Disillusioned.

To put it mildly. What’s worse, some of them really believed that they were doing the world a great service, like in the Medical Case, and they never repented. Outstanding, accomplished physicians at the top of their profession—they’d taken the Hippocratic Oath. How could they experiment on helpless men, women, and children? Because they saw them as mice, not people—sub-humans, untermenschen. Can you imagine how it felt seeing them get a few years in prison, then go back into society a couple of years later?

AW: Well, Stuckart’s freedom was short lived, yes? He was killed in a car crash right after he walked, wasn’t he?

Landis: A couple of years later, I think. I heard through very reliable sources that he was one of the first targets of the Mossad [the Secret Intelligence Service of Israel]. I know I didn’t shed a tear.

AW: So how do you see the Nuremberg Trials in terms of establishing new and binding international law?

Landis: A total failure.

AW: Really? Total failure?

Landis: Look at what’s happened since. The Soviets go into Afghanistan and slaughter the Afghans. Or how about the Ayatollah and all the international laws he broke? Look at what’s happened in China, Vietnam, and Cambodia—everywhere there’s crimes against humanity and war crimes. What’s stopped them? Did the Nuremberg precedent stop them? Has the World Court stopped them?

AW: How was the Nuremberg precedent supposed to stop those things?

Landis: By the nations of the world doing what’s right—coming together with the muscle to intervene. You gotta have a court and a tribunal, then the muscle to bring international criminals to the bar of justice. In small scale situations the United Nations can do that, but with larger nations, it is powerless. Politics overwhelm initiative and result only in rhetoric, but no action.

Back in 1947, we believed we were building a United Nations structure that could prevent future aggressive war, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Every nation that joins the United Nations signs its charter, Section 227 I think, that says you must respect human rights, can’t wage wars, and can’t run a police state. You can’t do it. Everyone signed it, and that has stopped it from happening, right?

AW: You had high hopes at first.

Landis: Hell yes! I made a lot of speeches to dozens of groups. When I came home, the LA Times wrote an article about me, and I was a little bit of a celebrity for a time. I talked to a lot of church groups and schools and talked about how the example of Nuremberg would help prevent another Nazi regime in the future. Now, I know that a lot of what our tribunals decided has been used since then in the few war crimes trials that have been held. So at least we created precedents, but those trials have only been small scale.

AW: So is that the only legacy of the Nuremberg Trials?

Landis: Well, maybe one other thing. Because of what we did at Nuremberg, it can be said that at one point in human history, and maybe only then, everyone agreed about what was right and what was wrong for nations, governments, and people to do to each other, that laws are laws and must be respected and enforced or millions die. And everyone agreed that the rights we believe in here in America apply to everyone, everywhere. They call them human rights now, not just inalienable rights. So, for just a few years, those who broke those laws in inconceivable ways were eventually hauled before the bar of justice, and many of them were punished.

Our prosecuting teams were made up of good men who believed in what we were doing, and we did our jobs by the letter of the law. In the end, there will always be leaders and nations like Hitler and Nazi Germany. I just hope we keep our muscles strong enough to stop them, and maybe that in itself is legacy enough and justice enough for those who died under the Third Reich.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments